Published online Jul 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i7.404

Revised: May 27, 2013

Accepted: June 19, 2013

Published online: July 27, 2013

Processing time: 80 Days and 16 Hours

Castleman disease often develops in the neck, mediastinum and pulmonary hilum. Its onset in the peritoneal cavity is very rare. The patient, a woman in her 70s, was referred to our department for a detailed examination of an abdominal mass. On abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography, a mass approximately 15 mm in diameter was noted in the hepatic S6. We attempted radical treatment and conducted a laparoscope-assisted right lobectomy. On the basis of histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed as having hyaline type Castleman disease in the liver, a very rare condition.

Core tip: We report a very rare case of hyaline-type Castleman disease in the liver. Castleman disease can occur wherever lymphoid tissue is found, although it rarely appears in the abdominal cavity, and is especially rare in the liver. The patient was suspected of having a malignant liver tumor because of positron emission tomography findings. No findings from diagnostic imaging specific to Castleman disease are known and it is, therefore, difficult to make a predictive diagnosis.

- Citation: Miyoshi H, Mimura S, Nomura T, Tani J, Morishita A, Kobara H, Mori H, Yoneyama H, Deguchi A, Himoto T, Yamamoto N, Okano K, Suzuki Y, Masaki T. A rare case of hyaline-type Castleman disease in the liver. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(7): 404-408

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i7/404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i7.404

Castleman disease, a lymphoproliferative disease with good prognosis that was first reported in 1954, presents with localized lymph node swelling[1]. Keller et al[2] divided this disease histopathologically into the hyaline type (characterized by hyperplasia of the hyalinated lymph follicles and vascularity accompanied by proliferation of vascular endothelial cell) and the plasma cell type (characterized by intense infiltration of plasma cells into the interfollicular tissue). It is now classified as an unexplained lymphoproliferative disease. Approximately 90% of cases are the hyaline vascular type and the other 10% are the plasma cell type[3]. The condition is known to develop in any age group regardless of gender. The hyaline type, which accounts for approximately 90% of all patients with Castleman disease, often develops in the neck, mediastinum, and pulmonary hilum. Its onset in the peritoneal cavity is very rare. Here we describe a very rare case of hyaline type Castleman disease in the liver.

The patient, a woman in her 70s, was referred to our department for a detailed examination of an abdominal mass. She had no noteworthy major complaint or disease history. Her mother had a history of colorectal cancer treatment and her husband had received liver cancer treatment. The patient developed epigastric pain in November 2011 and consulted a nearby clinic. At that time, an abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mass in the liver. She was then referred to our hospital.

Physical examination at our hospital revealed that the patient was 142 cm tall, weighed 47 kg, had a blood pressure of 143/63 mmHg, a heart rate of 71/min (regular), and a body temperature of 36.2 °C. No superficial lymph nodes were palpable. Chest auscultation revealed no abnormalities. The abdomen was flat, soft, and not tender. No noteworthy neurological abnormalities were found.

No noteworthy abnormalities were detected by blood tests. Tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, alpha-fetoprotein, and protein induced by vitamin K absense) were all within normal ranges.

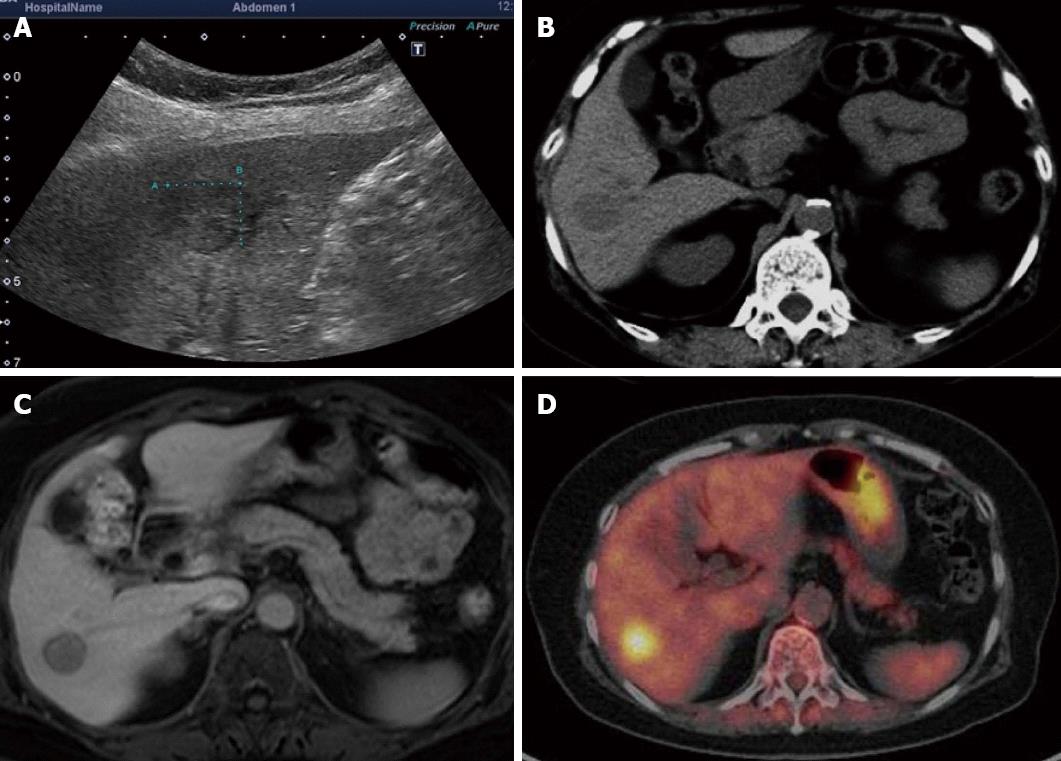

On abdominal ultrasonography, a hypoechoic mass approximately 15 mm in diameter was noted in the hepatic S6. Radiography using perflubutane as a contrast agent revealed contrast enhancement during the vascular phase and a defect during the late vascular phase.

A plain CT scan of the abdomen revealed a well-demarcated low absorption area dimly visible in the S6. On dynamic CT scan, a thin membrane-like contrast enhancement was noted in the periphery during the arterial phase although no evident contrast enhancement was seen inside the mass. A mass with slightly low internal absorption was seen during the portal phase. A mass with slightly higher internal absorption compared to normal hepatic parenchyma was noted during the equilibrium phase.

On abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a mass approximately 15 mm in diameter was visible in the hepatic S6 as a low signal intensity area on T1-weighted images and as a high signal intensity area on T2-weighted images. MRI using EOB Primovist disclosed a dimly contrast-enhanced mass during the arterial phase and a mass depicted as a low signal intensity area from the portal phase onward.

Positron emission tomography (PET) revealed enhanced accumulation with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 6.1 noted in hepatic S6 (Figure 1).

No noteworthy abnormalities were seen in upper/lower endoscopy.

On the basis of these test results, the patient was suspected of having a malignant liver tumor (similar to a poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocellular carcinoma). Because her hepatic reserves were favorable, we attempted radical treatment and conducted a laparoscope-assisted right lobectomy.

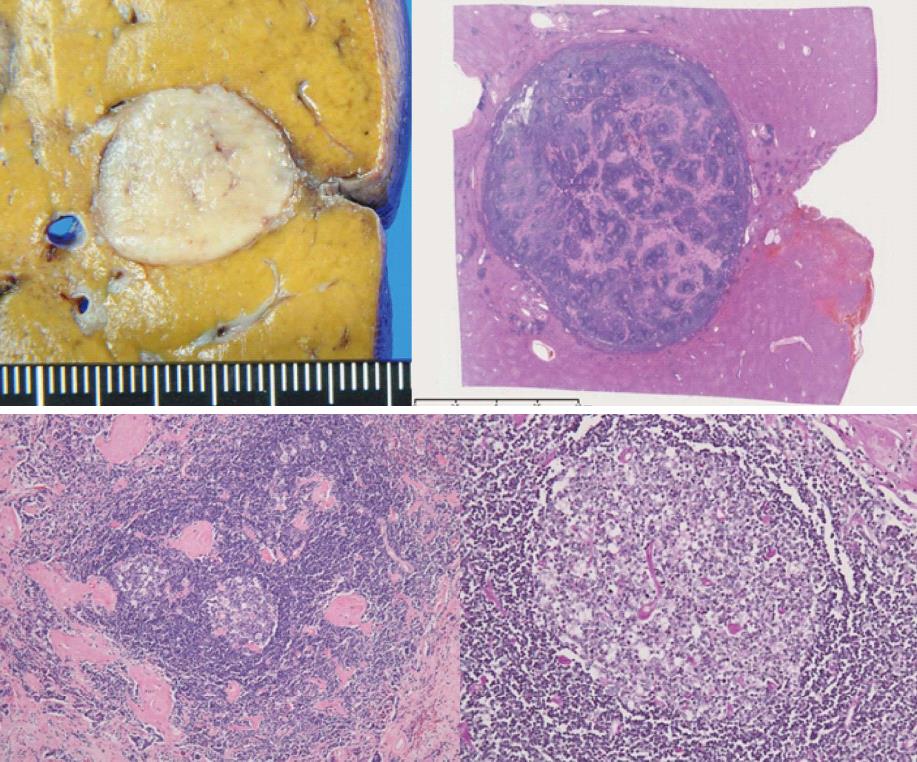

A white tumorous lesion approximately 20 mm in diameter and clearly distinguishable from surrounding tissue was noted.

Lymph follicle hyperplasia was noted in the affected liver tissue. Some follicles showed signs of vascular invasion, hyperplasia of the mantle layer, and the presence of multiple germ centers. Hyalinized interstitium was seen between follicles (Figure 2). There was no marked proliferation of lymphocyte-like atypical cells. Upon immunohistochemical staining, CD3, CD5, CD20, CD79a, CD10, CD21, CD23, and bcl-2 were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA was also negative. On the basis of these findings, the patient was diagnosed as having hyaline-type Castleman disease in the liver, a very rare condition. This case was treated using surgical resection only. At the present time, the patient is under follow-up without any further treatment and the disease has shown no signs of recurrence.

Castleman disease, a lymphoproliferative disease with good prognosis but without an identified cause, presents with localized lymph node swelling. It was first reported by Castleman et al[1]. Pathologically, it can be divided into hyaline and plasma cell types. Clinically, it is classified into unicentric and multicentric types. The development manner and treatment methods vary by type[2,4-7]. The sites frequently affected by this disease are reported to be the mediastinum (65%), neck (16%), abdomen (12%), and axilla (3%)[8]. However, Jang et al[4] reported 10 rare cases of Castleman disease that developed in the hepatic hilum. In many of these cases, the disease was of the hyaline type located in the vicinity of the liver. The development of this disease inside the liver, as in the present case, may be viewed as very rare.

Clinically, cases of this disease with a single lesion usually have good prognosis, while cases with multiple lesions tend to have poor prognosis. On the basis of these characteristics, cases of this disease with a single lesion are classified as unicentric Castleman disease and cases with multiple lesions as multicentric Castleman disease (MCD). Most cases of MCD are pathologically rated as the plasma cell type[9]. In terms of clinical symptoms, lymph node swelling is often confined to particular regions in cases of hyaline-type Castleman disease, and symptoms other than those related to compression are rare for this type. On the other hand, the plasma cell type often shows signs of chronic inflammation such as fever, arthralgia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation, weight loss, and systemic lymph node swelling[2]. These symptoms of the plasma cell type are sometimes accompanied by symptoms of Croe-Fukae syndrome (POEMS syndrome) such as polyneuritis, organ swelling, endocrinological abnormalities, M protein, and bone-sclerosing lesions[8,10].

No finding from diagnostic imaging specific to Castleman disease is known. When examined by ultrasonography, the affected area is often depicted as a well-demarcated hypoechoic mass with a homogeneous inside. On CT scan, a mass with high contrast enhancement, occasionally accompanied by calcification, is visible. When examined by MRI, this disease is often seen as a low signal intensity area on T1-weighted images and a high signal intensity area on T2-weighted images[11]. In fludeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET studies of Castleman disease sporadic moderate accumulation was noted in the mass[12,13]. Park et al[12] summarized the data from 10 cases, reporting that the mean SUV was 4.9 (range, 3.2-8.9). They added that this SUV is apparently lower than that known for high malignancy non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and close to that for low malignancy non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[12]. There are reports that FDG-PET gives positive findings in cases with non-malignant diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculoma, liver abscess, and chronic pancreatitis[14], indicating the need to bear in mind that patients with these inflammatory or granulomatous diseases can also be rated positive by FDG-PET.

Other conditions requiring distinction from this disease include liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, fibrohistiocytoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and lymphoma. These diseases are poor in specific characteristics revealed by diagnostic imaging, making it difficult to make a preoperative diagnosis of Castleman disease. A preoperative tumor biopsy is not recommended for reasons such as an inability to collect a sufficient amount of tissue and the possibility to induce tumor dissemination by biopsy. In the present case, the FDG-PET finding of accumulation in the liver suggested a malignant tumor (poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocellular carcinoma, metastatic liver cancer, or the like). We judged that this patient had a malignant tumor of hepatic origin for the following reasons: (1) absence of signs of malignancy revealed by upper/lower gastrointestinal endoscopy; and (2) absence of organs other than the liver showing abnormal accumulation during FDG-PET[8,15].

We attempted radical treatment by surgical resection in this case because of favorable hepatic reserves. However, there is no established method for treating Castleman disease[4]. It has been reported that in cases of hyaline-type Castleman disease with a single lesion, radical treatment with surgical resection alone is likely to be achieved and the prognosis is good. Although reports of the use of radiotherapy for cases not indicated for surgery have been published, the efficacy of radiotherapy remains controversial[5-7,16]. For plasma cell-type cases, treatment is sometimes attempted using cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone or using dexamethasone, which resembles the therapy used for non-Hodgkin’s disease[6,7]. In recent years, interleukin (IL)-6 has been suggested to be involved in the pathophysiology of Castleman disease, and cases responding well to anti-IL-6 therapy have also been reported[17].

It has been reported that the hyaline vascular type of disease often undergoes a gradual increase in lesion size over the course of several years or more after disease onset[3]. In the present case, surgical resection was used for both diagnosis and treatment since malignancy was not eliminated by the FDG-PET findings and because biopsy involved the risk of tumor dissemination. We believe that this strategy was rational for this case. Castleman disease is an unexplained lymphoproliferative disease that often develops in the mediastinum. As presented in this paper, we recently encountered a very rare case of this disease, hyaline type Castleman disease that developed inside the liver.

| 1. | Castleman B, Towne VW. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital; weekly clinicopathological exercises; founded by Richard C. Cabot. N Engl J Med. 1954;251:396-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Keller AR, Hochholzer L, Castleman B. Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972;29:670-683. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Seco JL, Velasco F, Manuel JS, Serrano SR, Tomas L, Velasco A. Retroperitoneal Castleman’s disease. Surgery. 1992;112:850-855. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Jang SY, Kim BH, Kim JH, Ha SH, Hwang JA, Yeon JW, Kim KH, Paik SY. A case of Castleman’s disease mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:53-57. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gaba AR, Stein RS, Sweet DL, Variakojis D. Multicentric giant lymph node hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:86-90. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Casper C. The aetiology and management of Castleman disease at 50 years: translating pathophysiology to patient care. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:3-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Rhee F, Stone K, Szmania S, Barlogie B, Singh Z. Castleman disease in the 21st century: an update on diagnosis, assessment, and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8:486-498. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bucher P, Chassot G, Zufferey G, Ris F, Huber O, Morel P. Surgical management of abdominal and retroperitoneal Castleman’s disease. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen KT. Multicentric Castleman’s disease and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:287-293. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Waterston A, Bower M. Fifty years of multicentric Castleman’s disease. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:698-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shin JH, Lee HK, Kim SY, Khang SK, Park SH, Choi CG, Suh DC. Castleman’s disease in the retropharyngeal space: CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1337-1339. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Park JB, Hwang JH, Kim H, Choe HS, Kim YK, Kim HB, Bang SM. Castleman disease presenting with jaundice: a case with the multicentric hyaline vascular variant. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:113-117. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Enomoto K, Nakamichi I, Hamada K, Inoue A, Higuchi I, Sekimoto M, Mizuki M, Hoshida Y, Kubo T, Aozasa K. Unicentric and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e24-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chander S, Westphal SM, Zak IT, Bloom DA, Zingas AP, Joyrich RN, Littrup PJ, Taub JW, Getzen TM. Retroperitoneal malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: evaluation with serial FDG-PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29:415-418. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Madan R, Chen JH, Trotman-Dickenson B, Jacobson F, Hunsaker A. The spectrum of Castleman’s disease: mimics, radiologic pathologic correlation and role of imaging in patient management. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer Diamantis I S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Li JY