Revised: November 4, 2012

Accepted: November 17, 2012

Published online: February 27, 2013

A 38-year-old female presenting with a high fever of 39 °C developed severe liver dysfunction and acute renal failure (ARF). In tests for a hepatitis associated virus, an Immunoglobulin M-anti-hepatitis B virus core antibody was the only positive finding. Moreover, the progression of ARF coincided with the pole period of liver damage and all the other assumed causes for the ARF were unlikely. Therefore, this case was diagnosed as ARF caused by acute hepatitis B. ARF associated with non-fulminant hepatitis has been infrequently reported, usually in association with acute hepatitis A. This case is considered to be an extremely rare and interesting case.

- Citation: Kishi T, Ikeda Y, Takashima T, Rikitake S, Miyazono M, Aoki S, Sakemi T, Mizuta T, Fujimoto K. Acute renal failure associated with acute non-fulminant hepatitis B. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(2): 82-85

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i2/82.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i2.82

Acute renal failure (ARF) with fulminant hepatitis is a common complication and the functional kidney failure induced by hepatocellular failure is known as hepatorenal syndrome[1]. On the other hand, ARF with non-fulminant acute hepatitis has also been reported, but this represents a different condition from hepatorenal syndrome and most cases are due to hepatitis A virus (HAV)[2-5]. Recently, a case of ARF accompanied with non-fulminant acute hepatitis presented to our clinic, and this hepatitis case was attributed to a hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. We report this case here because it is extremely rare.

The patient was a 38-year-old female who presented with a fever of 39 °C without respiratory symptoms or gastrointestinal symptoms in early November. The following day she received 1 g intravenous Ceftriaxone and 200 mg levofloxacin orally for 2 d. Diclofenac sodium of 25 mg was also administered only once. A few days later, general fatigue and nausea developed. On a return clinic visit, she had jaundice and had developed severe liver disorder [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 2751 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 5754 IU/L, total bilirubin (T-Bil) 4.7 mg/dL]. Therefore, the next day, she was referred to a nearby general hospital and was admitted. However, she was transferred to our hospital because of the development of ARF [blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 173.4 mg/dL, creatinine (Cr) 10.8 mg/dL].

There was nothing remarkable in her medical history and family history, and there was no record of transfusion. No weight gain or loss was recognized. The body temperature was 36.6 °C, blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg without orthostatic change, and the pulse rate was 70/min and regular. Her consciousness was alert and no involuntary movement, such as a flapping tremor, was recognized. Her skin had normal moisturization and did not have petechia or other eruptions. Her jugular venous pressure was normal. Her lungs were clear in auscultation. Her cardiac examination was normal, without a murmur or rub. The liver was palpable two finger-breadths in the right hypochondrium, but it was smooth and non-tender. There was no splenomegaly, and no fluctuation was recognized. She had slight pitting pretibial edema bilaterally.

Urine protein and occult blood were both strongly positive, and an erythrocyte, leukocyte, and a hyaline cast were found in the urinary sediment, but no granular or cellular casts were found. She was in an oliguric state and the fraction sodium excretion rate (FENa) rose by 15.5%. A complete blood count revealed anemia (Hb 9.5 g/dL) and slight thrombocytopenia. Prothrombin (PT) activity was slightly decreased (63%).

Biochemical findings revealed severe azotemia (BUN 201.5 mg/dL, Cr 14.05 mg/dL), remarkable hyperuricemia (UA 22.2 mg/dL), slightly elevated serum C-reactive protein CRP was 1.11 mg/dL, increased hepatic enzyme levels (AST 252 IU/L, ALT 2000 IU/L), and moderate hyperbilirubinemia, mainly direct bilirubin (T-Bil 4.5 mg/dL), whereas no increase in ammonia was observed, creatinine phosphokinase levels were normal, myoglobin was slightly increased, and endotoxin was negative.

The patient did not exhibit autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. Slight hypocomplementemia was found, but immune complex (C1q) was negative.

The findings of serological tests for herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, HAV, and E viruses were negative. As for HBV, the HB surface (HBs) antigen was negative, but the IgM-HB core (HBc) antibody was positive. In additional tests, the HB envelope (HBe) antigen was negative, the HBe antibody was positive, and IgG-HBc antibodies were weakly positive. The HBs antibody of a low titer showed a gradual rising trend.

On admission, 7 d after the onset of illness, she demonstrated extensive renal insufficiency and oliguria. Ultrasound revealed findings compatible with ARF, including increased bilateral kidney size, enlarged medullary pyramids and a distinct corticomedullary boundary.

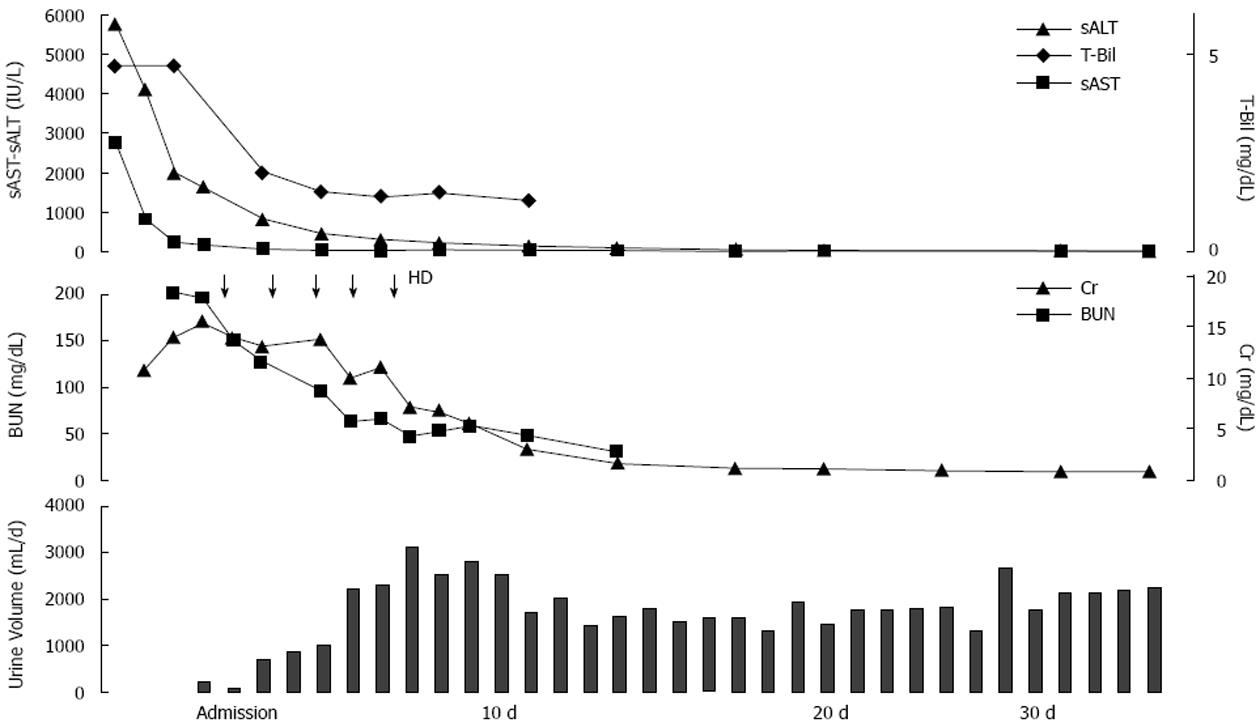

The ARF was thought to be strongly associated with acute hepatitis because it developed in parallel to the progression of the hepatic disorder. Hemodialysis was initiated since she was in an oliguric state. The PT activity, platelet count and bilirubin value did not aggravate after admission, but improved immediately. Moreover, no encephalopathy developed through the course. On the 7th day, the urine volume exceeded 2000 mL and hemodialysis was withdrawn (Figure 1).

Acute tubular necrosis was suspected as the cause of ARF because of the oliguria and increased FENa. However, percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed on the 16th day because of nephritis-like urine findings on admission.

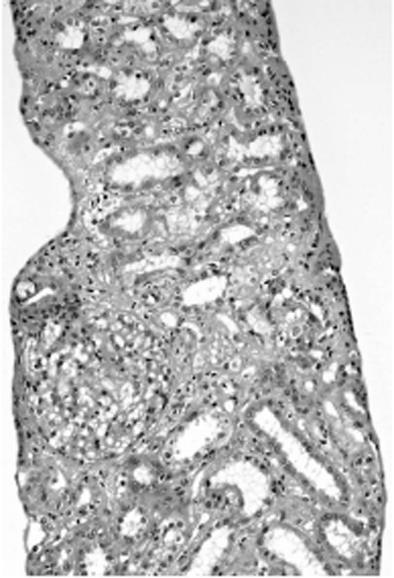

The light microscopic findings revealed no glomerulus change. Edema, degeneration and regeneration of the renal tubule epithelium, a slight cast in renal tubules, and slight cellular infiltration were recognized in the interstitium (Figure 2). Fluorescent antibody staining showed that IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C4, C1q, κ, and λ were all negative. An electron dense deposit was not revealed in the electron microscopic findings. On the basis of the above findings, she was diagnosed with acute tubular necrosis.

On the 35th day of hospitalization, she recovered and left the hospital. Her liver function was normalized before discharge, and her renal function including urinary findings normalized 1 mo after discharge.

Initially, hypovolemia due to acute hepatitis, hyperuricemia and administered medicines were suspected to be the cause of the ARF of this case. However, there was no sign of weight loss, hypotension or tachycardia, so hypovolemia was ruled out as a possible cause of this ARF. Remarkable hyperuricemia was not thought to be a possible cause of the ARF because the formation of the cast was found only in a small part of the kidney biopsy specimen. It was necessary to rule out interstitial nephritis caused by an antimicrobial agent or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, there was no clinical manifestation such as eosinophilia or pyrexia, and no findings that suggested interstitial nephritis in the kidney biopsy specimens. Therefore, it was unlikely to have been the cause of the ARF. Moreover, ARF due to NSAIDs through the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis was highly unlikely because it was used only one time. Therefore, acute hepatitis was diagnosed as the cause of this ARF because the ARF developed in association with the progression of hepatitis. The findings of IgM-anti-HBc antibodies of high titer, HBs antigen being negative in spite of the acme phase of hepatitis, and the occurrence of seroconversion suggested that this hepatitis was not generated from an HBV carrier[6], but was generated from a primary infection instead. An assay for hepatitis E infection that has been reported in a superinfection to HB[7] was negative.

There have been almost no reports of ARF associated with acute non-fulminant HB until now. Wilkinson et al[2] reported that only 2 cases of positive HB antigen were found in 12 cases of acute hepatitis with ARF. One of these cases was considered pre-renal ARF due to frequent emesis; another case was considered to be acute tubular necrosis to the point of oliguric ARF without proteinuria based on the findings of urine chemistry. The latter case died despite receiving peritoneal dialysis, and no renal biopsy was performed. Obana et al[8] also reported a similar case that was acute aggravation of hepatitis from an HBV carrier, and the findings of a renal biopsy 40 d after onset showed interstitial nephritis that was thought to have been due to concomitantly used drugs. However, in this case, a direct correlation between hepatitis and ARF was also suspected because of deposition of HBe antigen and IgG in the glomerulus.

Not only pre-renal factors, such as hypovolemia due to digestive symptoms, but also endotoxinemia[2], hyperbilirubinemia[3], vasoconstriction induced by the renin-angiotensin system[5], and glomerulonephritis induced by the immune complex[4] have been reported as factors associated with ARF associated with acute HA. Although such causes were considered, none were seen as a reasonable cause in the present case. There is a report [9] pointing out that a case of HA with ARF has a greater tendency to become more severe than one without ARF. It is noted that HAV induces a host immune response more powerfully than HB or HC viruses. Therefore, HA rarely becomes fulminant and common to heal as acute hepatitis.

The considerable rise of aminotransferase in the current patient was different from common acute HB. The HB antigen was already negative and the HB antibody was developing during the phase when the level of aminotransferase increased. This was thought to be due to a strong immune reaction, known as the hyperimmune response[6] in severe acute HB. The mechanism of the hyperimmune response has not been unexplained. The specific mechanism in ARF associated with acute HA is also unclear, but a common mechanism in cases of such severe acute hepatitis has been suggested as a cause of ARF. Moreover, since the seriousness of hepatitis correlates with the cause of co-morbid ARF, it is possible that there may be some pathological condition overlapping with ARF in fulminant hepatitis. The current case was thought to have been caused by sudden hepatic cell annihilation due to a non-typical strong immune reaction as in acute serum hepatitis, although the details were indistinct. This abnormal state was thought to induce ARF as can be seen in an acute HA case.

Acute hepatitis was suspected because of the preceding pyrexia and remarkable liver injury. Generally, HB antigens are only measured when screening for a HB virus infection, but the measurement of IgM-HBc established the diagnosis for this case. The phenomenon of the hyperimmune response thus brings to mind past cases that may have not reached a diagnosis of acute HB. The current case suggested that not only acute HA but also HB may be associated with ARF. Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to check for HB in addition to HA when a patient presents with ARF associated with acute hepatitis.

| 1. | Ring-Larsen H, Palazzo U. Renal failure in fulminant hepatic failure and terminal cirrhosis: a comparison between incidence, types, and prognosis. Gut. 1981;22:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wilkinson SP, Davies MH, Portmann B, Williams R. Renal failure in otherwise uncomplicated acute viral hepatitis. Br Med J. 1978;2:338-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kramer MR, Hershko C, Slotki IN. Acute renal failure associated with non-fulminant type-A viral hepatitis. Clin Nephrol. 1986;25:219. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Chio F, Bakir AA. Acute renal failure in hepatitis A. Int J Artif Organs. 1992;15:413-416. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Phillips AO, Thomas DM, Coles GA. Acute renal failure associated with non-fulminant hepatitis A. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:156-157. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Arakawa Y, Kawamura F, Okubo H, Tanaka N, Moriyama M, Suzuki K, Ono Y, Matsumura H. [Infection and prevention of hepatitis C virus in medical personnel]. Nihon Rinsho. 1995;53 Suppl:435-450. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Coursaget P, Buisson Y, N’Gawara MN, Van Cuyck-Gandre H, Roue R. Role of hepatitis E virus in sporadic cases of acute and fulminant hepatitis in an endemic area (Chad). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:330-334. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Obana M, Nobuoka T, Tomii M, Matsuoka Y, Hanada T. [A case of acute renal failure showing deposition of hepatitis Be antigen in glomeruli associated with acute exacerbation of hepatitis B (not fluminant type)]. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1985;27:1467-1473. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nakano A, Watanabe N, Matuzaki S. [The significance of acute renal failure in fulminant hepatitis--a comparison between type B and non B hepatitis]. Nihon Rinsho. 1995;53 Suppl:535-539. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer Chen F S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Yan JL