Published online Dec 27, 2012. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.394

Revised: September 2, 2012

Accepted: November 17, 2012

Published online: December 27, 2012

We describe a patient with sudden onset of abdominal pain and ascites, leading to the diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Her presentation was consistent with acute liver cyst rupture as the cause of her acute illness. A review of literature on polycystic liver disease in patients with ADPKD and current management strategies are presented. This case alerts physicians that ADPKD could occasionally present as an acute abdomen; cyst rupture related to ADPKD may be considered in the differential diagnoses of acute abdomen.

- Citation: Chaudhary S, Qian Q. Acute abdomen and ascites as presenting features of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. World J Hepatol 2012; 4(12): 394-398

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v4/i12/394.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.394

Sudden onset of abdominal pain and ascites usually signify critical illness often requiring urgent intervention. We describe a patient with such presentation where investigations led to an unanticipated diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), a hereditary disease characterized by adult onset progressive development and enlargement of cysts in the kidneys and other organs including the liver. It has been known that clinical presenting features and manifestations at the early stages of ADPKD are mostly insidious[1,2]. Acute abdomen with ascites as a presenting feature of ADPKD has not been previously described.

A 45-year-old female presented to a local emergency department (ED) with complaints of acute onset upper abdominal pain and distension associated with nausea and vomiting.

Her medical history included well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia and hypothyroidism for approximately two years. Her medications included daily enalapril 10 mg, rosuvastatin 10 mg, levothyroxine 50 mg and vitamin D supplement. She worked full-time as a physician and was mother to five children (ages 5 to 14 years) with the last two children being twins. Her pregnancies were uneventful except for the last pregnancy (with the twins) about six years ago; she had transient thrombocytopenia and mild liver enzyme elevation prior to the delivery which resolved promptly after the delivery. Reports of ultrasound examinations during her pregnancies did not indicate presence of hepatic or renal cysts. She had been on hormonal contraceptives intermittently with a cumulative duration of about 20 years. She denied a known family history of ADPKD.

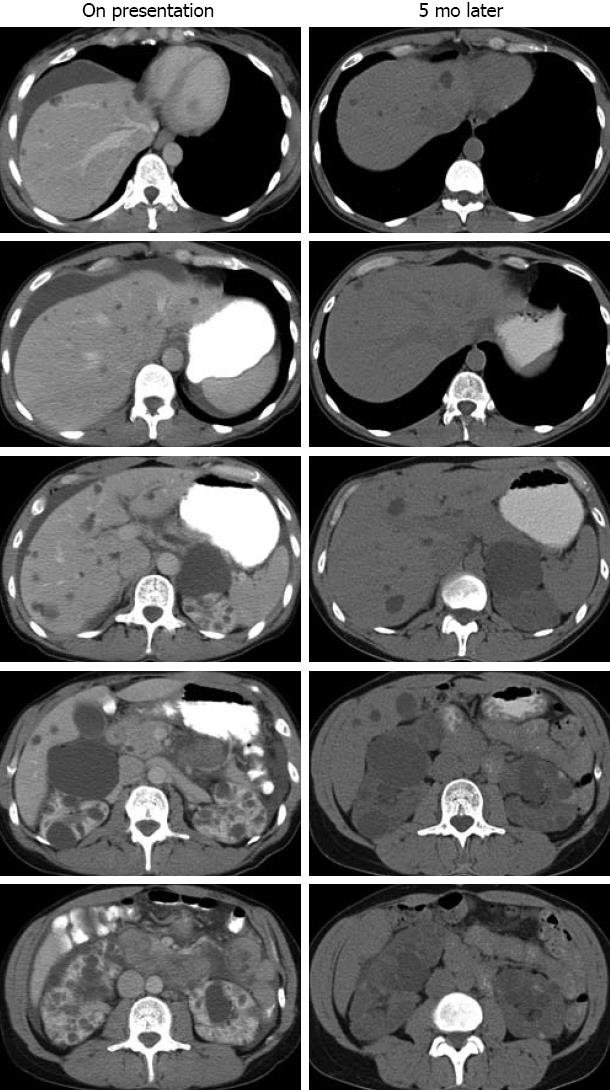

On the day of her presentation to the local ED, while at work, she developed a sudden-onset sharp upper abdominal pain, associated with shortness of breath and a feeling of abdominal fullness. She felt nauseated and vomited several times. She was rushed to the ED, where her vital signs were found to be normal. Her abdomen was mildly distended and tender on palpation in the upper quadrants with some guarding. Laboratory studies showed hemoglobin 12.9 mg/dL, leukocytes 7.3 × 109 cells/mL, albumin 4.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 26 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 45 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 66 U/L, bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 19 mg/dL, creatinine 1.1 mg/dL, and urinalysis was unremarkable. Her serum amylase and lipase were normal. Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed perihepatic ascites, multiple cysts throughout the liver with the largest cyst being 1.7 cm in diameter, and numerous cysts in the kidneys. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) confirmed perihepatic ascites and the benign-appearing cysts in the liver and kidneys (Figure 1, left). She was hospitalized for monitoring and treated with intravenous fluids and antiemetics (ondansetron). The following day, an esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy with random biopsy was performed which was without abnormality. Her pain, nausea and vomiting subsided, and she was discharged. A week later, she underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intra-operative inspection showed no abnormality except for the visible fluid-filled hepatic cysts. The pathology of the gallbladder was normal.

Five months later, she presented to our institution for a second opinion. She was asymptomatic and physical examination was unremarkable. Her medications were unchanged. An abdominal CT scan showed both liver cysts and bilateral kidney cysts (Figure 1, right), consistent with ADPKD. In retrospect, her acute abdomen and ascites were consistent with hepatic cyst rupture.

In this patient, the acute abdomen with ascites was the presenting feature of what turned out to be ADPKD. ADPKD in her was diagnosed based on the findings of numerous fluid-filled cysts in bilateral kidneys and liver, and the absence of features to suggest any alternative diagnosis. She did not have a positive family history which could be consistent with the general observation of de novo PKD gene mutations in a minority of ADPKD patients (5%-10%)[3]. Gene based diagnostic study is not required as the clinical presentation and radiographic findings are the gold standard for establishing a diagnosis[4].

Although all ADPKD patients develop kidney cysts, at the early stages of the disease (when the size of the affected organs are not significantly enlarged), the majority of the patients are asymptomatic or symptoms are so mild that often go unnoticed, such as reduction in urine concentration capacity. In a case series of 171 ADPKD patients, symptoms that led to investigation and ultimate diagnosis only accounted for 37.4% of the patients[5]. The most common symptoms were back pain (17.4%), gross hematuria (16.4%) and non-specific abdominal pain (16.4%). Although known to occur rarely in ADPKD patients with late stage cystic disease and kidney failure[6,7], liver cyst rupture leading to acute abdomen and ascites as initial symptoms of ADPKD has not been previously described.

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is the most frequent extra-renal manifestation in ADPKD, yet, it is clinically silent in majority of cases and only infrequently medical attention is needed. The following is an overview on its natural history, complication, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies.

Liver cysts usually start to appear after ADPKD patients reach puberty; by age 30 years, up to 94% of affected individuals have detectable PLD by imaging studies[8,9]. With age, almost all ADPKD patients have varying degrees of PLD. Significant variations can occur, even among affected individuals from the same family. However, for each patient, liver cysts grow steadily over time in both number and size. Although liver cysts may be innumerable, majority (approximately 80%) of the patients remain asymptomatic[10]. A minority of patients with a few large dominant cysts or with severe cystic liver enlargement develop symptoms, including pain from cyst growth, cyst hemorrhage, cyst infection and symptoms of compression to adjacent organs due to mass effects from cystic liver. It has been observed that ADPKD patients on dialysis or following transplantation are more likely to develop symptoms resulting from the mass effect or from cyst-related complications such as rupture, hemorrhage, or infection[8]. Spontaneous cyst rupture into the peritoneal cavity is extremely rare.

Although ADPKD gene mutations are well known to cause cystic liver phenotype, the precise pathogenesis for the development and enlargement of liver cysts has not been fully elucidated. Morphological studies of individual liver cysts reveal that cysts originate from biliary microhamartomas (also termed Von Meyenburg’s complexes that arise from proliferation of biliary ductules)[11] and from peribiliary glands[12]. Liver cysts are lined with epithelium of biliary origin[13] and, with progressive growth, cysts become detached from their origins. It is believed that the liver cyst growth is attributable to concerted effects of proliferation in cyst-lining epithelia, solute and fluid secretion into the cysts, remodeling of cyst-surrounding matrix and neovascularization[14].

Estrogen has been shown to influence the development and progression of liver cysts[15]. Biliary epithelia (cholangiocytes) and cyst-lining cells in ADPKD, in contrast to normal liver parenchymal cells, express estrogen receptors aberrantly[16]. Estrogen is able to act directly through estrogen receptors and indirectly by potentiating the effects of growth factors to promote cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion[17]. Moreover, through potentiating the effects of vascular endothelial growth factor, estrogen promotes adaptive angiogenesis, vital for cyst growth[18]. Estrogen therefore affects multiple aspects in promotion of cyst growth. Consistent with these data, severe degree of cystic liver enlargement occurs mostly in female patients, especially in multiparous women and women on oral contraceptive or estrogen replacement therapy[15,19]. Our patient had multiple pregnancies and had also been on hormonal contraceptive for many years. It is tempting to speculate that her estrogen exposure over the years might have contributed to her cystic liver disease and her dramatic presentation.

PLD is diagnosed by imaging studies, including ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Serum biochemical profile is typically normal and synthetic functions of the liver are preserved in virtually all cases. The only laboratory abnormalities seen in severe PLD are mild elevations of γ-glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase. Among imaging studies, ultrasound is preferred because of its low cost and lack of radiation. However, CT and MRI are more sensitive and accurate in detecting the number and size of liver cysts.

PLD should be differentiated from simple liver cysts, which often occur in normal individuals with age (up to four cysts at age 60 years)[15]. PLD should also be differentiated from occasional cysts associated with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). ARPKD is a rare (1:20 000) disease with congenital hepatic fibrosis as its major hepatic manifestation. Occasionally, liver cysts in PLD may also be confused with cystadenomas[20], especially when cysts contain hemorrhagic fluids. In such cases, further investigation and close follow-up are necessary. In our patient, there were no clinical or imaging evidences of these conditions.

Most cases of PLD require no treatment. Symptomatic PLD requires interventions to reduce cyst volume and liver size. To date, apart from avoidance of estrogen, no specific medical regimen has been established to halt the PLD development or to retard PLD progression. Invasive management strategies including percutaneous cyst aspiration with or without sclerosis, laparoscopic cyst fenestration, combined liver resection and cyst fenestration, and rarely, liver transplant have been the treatment modalities, aimed to palliate symptoms[21].

Percutaneous cyst aspiration and sclerosis under ultrasound or CT guidance is an effective modality to treat large dominant cysts that are not numerous. Cyst aspiration alone is often carried out diagnostically to determine whether there is a direct correlation between the cysts and the patient’s symptoms. Without the sclerosing therapy, however, cysts often re-expand in weeks to months following the procedure. Sclerosing therapy reduces the possibility of cyst re-expansion. Sclerosing therapy constitutes injection of an appropriate volume (approximately 25% of the aspirated cyst fluid volume) of 95%-99% ethanol or acidic solutions of tetracycline or minocycline into the cyst following cyst fluid aspiration. The patient then assumes different physical positions to ensure a maximum contact between the sclerosing solution and cyst-lining epithelia. The sclerosing fluid is then aspirated. This method carries approximately 70%-90% success rate of cyst obliteration[22]. For cysts with a diameter > 10 cm, repeat aspiration and sclerosis may be necessary for a sustained cyst obliteration[23].

More invasive surgical interventions are reserved for patients with severely symptomatic hepatomegaly due to PLD. Schnelldorfer et al[21] retrospectively studied 141 patients with PLD who underwent partial hepatic resection with remnant cyst aspiration, cyst fenestration alone, or orthotopic liver transplantation for symptoms or complications related to PLD at Mayo Clinic Rochester. Based on the experience, they propose to devise treatment plans for PLD patients on the basis of their clinical and radiographic features. They have classified PLD patients into four types, types A to D. Patients with no clinical symptoms or mild symptoms are classified as type A and no surgical treatment is indicated. Patients with moderate to severe symptoms with large-sized dominant cysts and preservation of at least two sectors of normal liver parenchyma are classified as type B and they should be considered for cyst fenestration. Those with severe symptoms associated with enlarged liver but having more than one sector of normal liver parenchyma are classified as type C for whom partial liver resection with remnant cyst fenestration may be considered. Patients with severely enlarged liver and with little normal liver parenchyma are classified as type D and the only treatment option for these patients is liver transplant. Although these operative treatments offer sustained improvement in performance and health status, they are technically demanding and perioperative complications are substantial. For instance, liver resection with remnant cyst fenestration carries overall morbidity of 60%-70%, including biliary leak and ascites. For liver transplant, survival rate seems lower than in non-PLD patients with liver transplant. Thus, for individual patients, treatment choices depend on local expertise, which is one of the most critical factors that predict success. Referral to a tertiary center with adequate expertise would more likely result in an optimal treatment outcome.

In summary, although typically asymptomatic, a subset of patients with PLD related to ADPKD may present with abdominal discomfort. The degree of symptoms depends on the extent and rapidity of liver cyst growth. As shown in this case, sudden rupture of hepatic cyst can occur and be an initial presenting feature of PLD. Though not previously described, such an occurrence is not entirely surprising, as rupture can conceivably occur in expanding superficial cysts. Thus, PLD and ADPKD should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses in patients with such a presentation. Conservative management, at least in this case, seemed to have sufficed. Whether such rupture would recur is uncertain and warrants ongoing follow up.

The authors thank the patient for her permission to report this case.

| 1. | Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 957] [Cited by in RCA: 1020] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grantham JJ. Clinical practice. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1477-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Harris PC, Torres VE. Polycystic Kidney Disease, Autosomal Dominant. Seattle (WA): Gene Reviews 1993; . |

| 4. | Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, Paterson AD, Magistroni R, Dicks E, Parfrey P, Cramer B, Coto E, Torra R. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bajwa ZH, Sial KA, Malik AB, Steinman TI. Pain patterns in patients with polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1561-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chung TK, Chen KS, Yen CL, Chen HY, Cherng WJ, Fang KM. Acute abdomen in a haemodialysed patient with polycystic kidney disease--rupture of a massive liver cyst. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1840-1842. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Carels RA, van Bommel EF. Ruptured giant liver cyst: a rare cause of acute abdomen in a haemodialysis patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Neth J Med. 2002;60:363-365. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Torres VE. Treatment of polycystic liver disease: one size does not fit all. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:725-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, King BF, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA, Kenney PJ, Harris PC. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2122-2130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 584] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bae KT, Zhu F, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Baumgarten DA, King BF, Wetzel LH, Kenney PJ. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatic cysts in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Von Meyenburg H. Uber die cystenleber. Beitr Path Anat. 1918;64:477. |

| 12. | Moschcowitz E. Non-parasitic cyst (congenital) of the liver with a study of aberrent bile ducts. Amer J Med Sci. 1906;131:674-699. |

| 13. | Bistritz L, Tamboli C, Bigam D, Bain VG. Polycystic liver disease: experience at a teaching hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2212-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qian Q, Torres VE, Somlo S. Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Fibrocystic diseases of the liver. New York: Humana Press 2010; . |

| 15. | Qian Q, Li A, King BF, Kamath PS, Lager DJ, Huston J, Shub C, Davila S, Somlo S, Torres VE. Clinical profile of autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:164-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alvaro D, Mancino MG, Onori P, Franchitto A, Alpini G, Francis H, Glaser S, Gaudio E. Estrogens and the pathophysiology of the biliary tree. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3537-3545. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Alvaro D, Metalli VD, Alpini G, Onori P, Franchitto A, Barbaro B, Glaser SS, Francis H, Cantafora A, Blotta I. The intrahepatic biliary epithelium is a target of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor 1 axis. J Hepatol. 2005;43:875-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mancino A, Mancino MG, Glaser SS, Alpini G, Bolognese A, Izzo L, Francis H, Onori P, Franchitto A, Ginanni-Corradini S. Estrogens stimulate the proliferation of human cholangiocarcinoma by inducing the expression and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sherstha R, McKinley C, Russ P, Scherzinger A, Bronner T, Showalter R, Everson GT. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectively stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1282-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Erdogan D, Lamers WH, Offerhaus GJ, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Cystadenomas with ovarian stroma in liver and pancreas: an evolving concept. Dig Surg. 2006;23:186-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schnelldorfer T, Torres VE, Zakaria S, Rosen CB, Nagorney DM. Polycystic liver disease: a critical appraisal of hepatic resection, cyst fenestration, and liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Blonski WC, Campbell MS, Faust T, Metz DC. Successful aspiration and ethanol sclerosis of a large, symptomatic, simple liver cyst: case presentation and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2949-2954. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Yoshida H, Onda M, Tajiri T, Arima Y, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Akimaru K. Long-term results of multiple minocycline hydrochloride injections for the treatment of symptomatic solitary hepatic cyst. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:595-598. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Hatim Mohamed Yousif Mudawi, Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Internal medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Sudan. Po box 2245 Khartoum, Sudan; Pierluigi Toniutto, Professor, Internal Medicine, Medical Liver Transplant Unit, University of Udine, P. zale S.M. della Misericordia 1, 33100 Udine, Italy

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY