INTRODUCTION

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and hepatocellular adenoma (HA) are both benign nodular hepatocellular lesions, presenting mainly in women of childbearing age in non-cirrhotic, non-fibrotic livers. FNH is the second most common benign hepatic tumor in adults and represents about 8% of all primary hepatic lesions[1]. Typically, FNH is an incidental finding in symptom-free patients. It presents as a palpable abdominal mass in 2% to 4% of patients, while hepatomegaly and fever occur in less than 1 percent of cases. Spontaneous rupture leading to hemorrhage is extremely rare and there is no incidence of malignant transformation of FNH[2,3]. Levels of serum alpha-fetoprotein are within normal range[4,5].

HA is the third most common benign liver lesion in adults, after hepatic hemangioma and FNH, and is 3 to 10 times less common than FNH[6,7]. A 30 to 40 fold increase in the incidence of HA has been assumed in long term users of oral contraceptives, with a base level incidence of 1 per million in women using oral contraceptives for less than 24 mo or not at all[8,9]. As in FNH, patients with HA are often asymptomatic. Atypical abdominal discomfort is reported in about 30% to 40% of patients and in a small number of cases a palpable mass is present. Large lesions may cause more severe complaints such as abdominal pain; hypovolemic shock after rupture or intratumoral hemorrhage has been observed in some cases. As with FNH, serum alpha-fetoprotein levels are within normal range[4,10].

Simultaneous presence of FNH and HA is very rare and only few cases have been published in the pertinent literature[11-14]. We report a case of a young female without any predisposing risk factors with simultaneous existence of FNH and HA. The diagnostic procedure, therapeutic management and possible pathogenic setting are discussed herein.

CASE REPORT

An 18 year old nulliparous female patient presented to the emergency department complaining of acute abdominal pain. She was 1.65 m tall and weighed about 55 kg upon admission (body mass index 20.2). The patient denied any oral contraceptive pill use, tobacco or alcohol consumption and there was no history of hepatitis. Hepatitis infection markers were negative. Gynecological history was unremarkable, with normal pubertal/post-pubertal development and menstruation. Past medical history was likewise unremarkable. The pain was localized in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen and was accompanied by a slight elevation of body temperature (37.2 °C). The patient did not complain of vomiting, change in bowel habits or any urinary symptoms. Clinical examination did not demonstrate any suspicious signs of high endogenous androgen activity. Routine laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, biochemical profile with liver function tests and α-fetoprotein measurement, were within normal range.

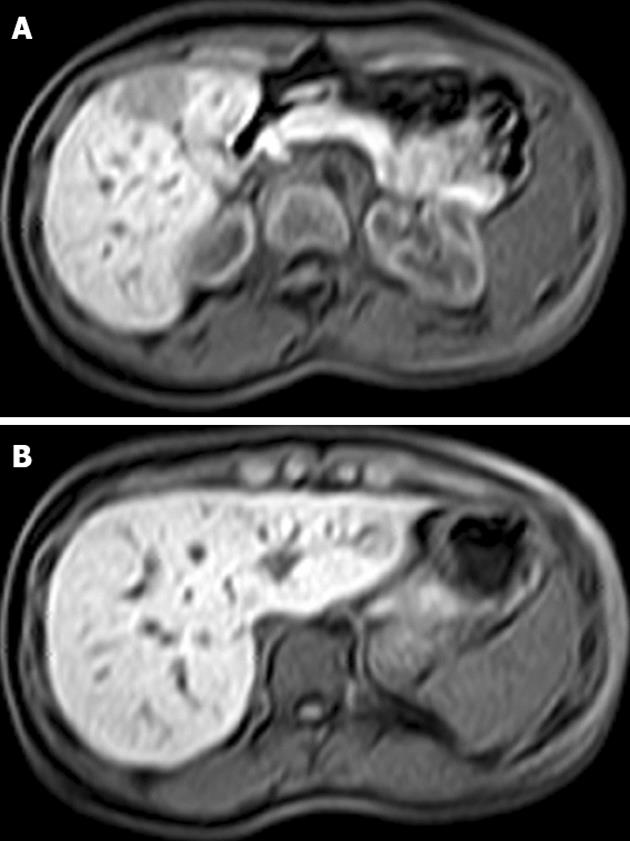

Emergency ultrasound showed a mass of approximately 6 cm in diameter located in the right liver lobe. Upper abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 6 cm lesion in the right liver lobe (segments V and VI) and a smaller one (2.5 cm) in the left lobe (segment III), respectively (Figure 1). However, the MRI findings were not specific for the larger lesion in the right lobe (Figure 1A). In view of the patient’s symptoms and the lack of a confirmed diagnosis based on preoperative imaging examinations, we opted for prompt surgery.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver showing a 6 cm lesion in segments V and VI (A) and a smaller lesion of 2.

5 cm in segment III (B).

The patient underwent a bisegmentectomy V-VI and a wedge resection of the lesion in segment III by laparotomy. Total operating time was 125 min and blood loss was minimal. Portal triad clamping was not performed at any stage of the operation. Perioperative or postoperative blood or plasma products transfusion was not required. The postoperative course ran uneventfully and the patient was discharged on the fourth postoperative day in good general condition.

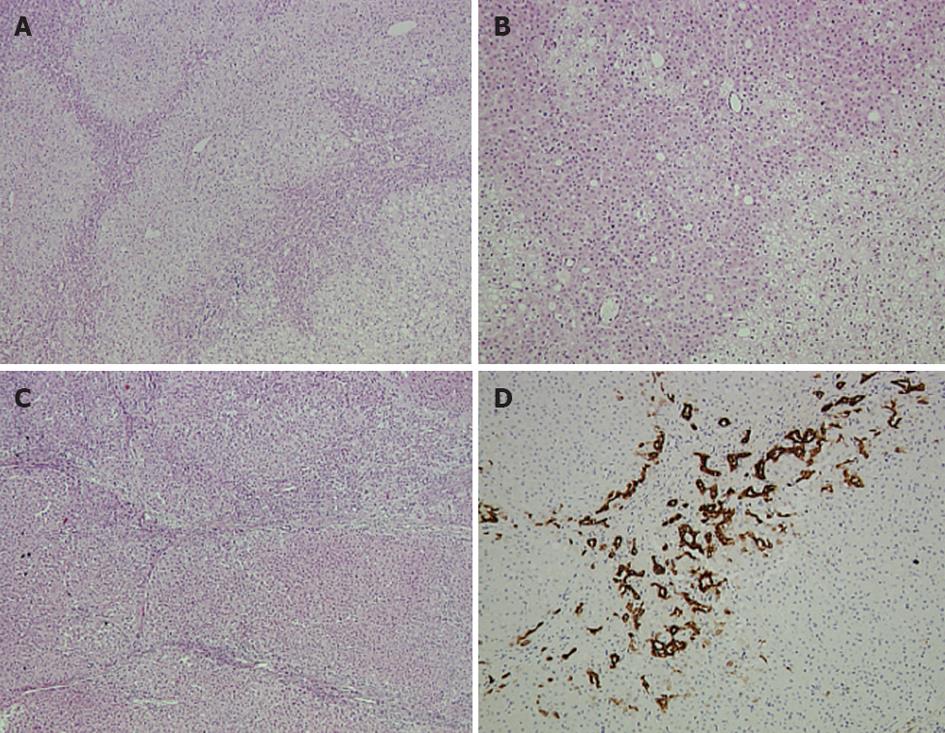

Pathology report of the larger lesion in segments V and VI revealed a non-encapsulated hepatocellular neoplasm composed of benign-looking hepatocytes, arranged in sheets and thin cords, occasionally forming rosette-like structures (Figure 2A and B). Isolated arteries were also present. Two different hepatocellular populations were discernible, demonstrating a zonal distribution. In the periphery of the lesion, eosinophilic hepatocytes were present alternately with larger hepatocytes, thus forming a vague lobulation. Abortive portal-tract like structures with thin fibrous septa and mild ductular reaction were observed mainly towards the periphery of the lesion. Overall, the tumor was characterized by mild to moderate steatosis, lipofuscinosis, a well-developed reticulin network, no cytological abnormalities and no inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical examination showed absence of nuclear expression of beta catenin, while serum amyloid A gave a weak, non-specific reaction. Cytokeratin 7 was positive in the abortive bile ducts and ductules and in a few tumor cells at the periphery of the fibrous septa. Cytokeratin 19 was positive only in rare ductular structures. Glutamine synthetase exhibited a patchy positive expression, while L-FABP antibody was not attenuated compared to normal parenchyma. Pathology and immunohistochemistry findings supported the diagnosis of hepatocellular adenoma partly featuring a telangiectatic variant.

Figure 2 Pathology report of the larger lesion in segments.

A, B: Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of the hepatocellular adenoma showing a vague lobularity created by two hepatocytic populations with zonal arrangement. Rosette-like formations are apparent (A ×5, B ×10); C: HE staining of the focal nodular hyperplasia lesion showing nodularity and thin fibrous septa (×5); D: Ductular reaction depicted by cytokeratin 7 expression (×10).

The pathology report of the resected segment III revealed a non-encapsulated, circumscribed hyperplastic hepatocellular lesion. The tumor was divided into smaller nodules by fibrous septa, which contained dystrophic arteries (Figure 2C). Prominent ductular reaction and mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrates were also observed (Figure 2D). A well developed reticulin network supported the tumoral hepatocytes that showed no cytological atypia and minimal steatosis. The diagnosis was that of focal nodular hyperplasia.

At present, 6 mo after the operation, the patient remains asymptomatic with normal hepatic function tests and ultrasound and MRI imaging show liver regeneration without signs of tumor relapse.

DISCUSSION

We herein describe a case of a young female patient, with no history of oral contraceptive use or other risk factors, exhibiting simultaneous occurrence of FNH and HA in different liver segments.

FNH and HA are two benign liver lesions that very seldom co-exist. The pathogenesis of FNH and HA is considered to be different. On one hand, the exact etiology of FNH is not completely understood. It is generally suggested that FNH originates from arterial malformation, which causes a hyperplastic reaction of normal liver cells to either hyperperfusion or hypoxia[15]. As hyperplastic reactions respond to cell proliferation mechanisms, FNH does not undergo any malignant transformation. Several clinical observations strengthen the above hypothesis as FNH may coexist with hepatic hemangioma or telangiectasia[13,16-19]. Scalori et al[20] suggested that cigarette smoking might be an elevated risk index for FNH. On the other hand, HA seems to have a causal relationship with exogenous administration of male and female sex hormones. The use of oral contraceptives provides convincing evidence that the incidence and size of HA is dose and duration dependent[9]. Moreover, the pertinent literature reports sporadic cases of HAs occurring in patients with elevated levels of endogenous androgens, sex hormone imbalance or exogenous administration of androgens as a treatment option for aplastic anemia[12,21-23]. A special form of HA has been described where multiple adenomas occur with at least ten lesions in the liver parenchyma, a condition designated as liver adenomatosis[24]. The etiology of liver adenomatosis is unknown but there is some evidence supporting common pathways with HA[25]. The fact that this condition is often found in women with a history of estrogen exposure could imply that liver adenomatosis is an advanced form of HA. Obesity, positive history of viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse and metabolic diseases, such as Von Gierke glucogen storage disease, have also been depicted as possible risk factors for HA by some authors[26-28].

Recently, a meticulous analysis of a large series of HA by a French collaborative group resulted in their classification of 4 subtypes[10]. The first group includes heavily steatotic adenomas exhibiting biallelic inactivation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha. The second group is characterized by activating mutation of beta catenin and a higher risk for malignant transformation. The third group is defined by the presence of inflammatory infiltrates, sinusoidal dilatation, fibrous septa with ductular reaction and abortive portal tracts, while the fourth group includes adenomas that cannot be classified in any of the above three subtypes. Of note, the newly characterized entity previously called telangiectatic FNH, now believed to be a variant of liver cell adenoma, is classified in the third group of inflammatory/telangiectatic adenomas[29]. The adenoma described herein shared some morphological features with the telangiectatic subtype. However, it was categorized into the fourth group (adenoma not otherwise classified) due to the absence of pathognomonic telangiectatic and inflammatory findings.

It is well established that HA and FNH are two distinct entities with specific histological and molecular features. However, differential diagnosis between them may be difficult in liver resection specimens or liver biopsy-obtained material. It is most likely that in the near future diagnosis will be facilitated by the molecular alterations detected in such lesions. Liver cell adenomas, including subtypes previously called telangiectatic FNH, are monoclonal tumors[26,30]. Conversely, clonal analysis on FNH lesions indicated a monoclonal origin in 14% to 50% of cases, depending on the samples examined and molecular techniques carried out. Furthermore, the mRNA ratio of angiopoietin genes (ANGPT-1 and ANGPT-2, respectively) is found to be attenuated in typical FNH compared to HA[31].

The simultaneous presence of both FNH and HA in the same patient is very rare and only a few cases have been described in the pertinent literature[11-14]. The largest report is the work of a French group that studied the co-existence of benign liver tumors[14]. In this study, HA and FNH were found in the same liver in 5 out of 30 cases with multiple benign liver lesions over a period of 12 years[14]. It is of note that in all cases published in the literature, patients were either on exogenous administration of oral contraceptives or had endogenous elevated sex hormones, conversely to our case presented herein. Laurent et al[14] reported that simultaneous occurrence of HA and FNH could be generated secondary to systemic and local angiogenic abnormalities by oral contraceptives, tumor induced growth factors or thrombosis and local arterio-venous shunting.

In our case, the young female patient had no clinical signs of androgen hyperactivity, nor did she receive any oral contraceptives. She did not consume any tobacco or alcohol and her BMI was within normal range. She also had a negative history of viral hepatitis with normal serum hepatitis virus infection assays. Thus, our report is the first in the literature to describe the simultaneous occurrence of HA and FNH without the presence of any known risk factors. In our case, there is no obvious common pathogenic mechanism and the co-existence of the lesions could be incidental. However, the presence of some morphological overlapping features does not exclude the possibility of a commonly shared causative relationship. Deeper knowledge of the molecular background of those two tumors could help recognize the exact association between them.

In recent years, there has been an increased incidence in the diagnosis of FNH and HA. The reason for this fact is increased administration of oral contraceptives on one hand and, on the other hand, imaging modalities evolution. This reality urges the need for providing secure preoperative diagnostic criteria in order to avoid an unnecessary operation and, more importantly, not to skip a necessary resection of a potential malignant tumor in a young or middle aged female. Many imaging modalities are used to diagnose FNH and HA. Especially for FNH, diagnosis can be achieved with high certainty on several imaging studies based on typical features. However, there are atypical imaging findings in both FNH and HA[32]. Sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic imaging has been improved for the diagnosis of FNH, while the gold standard for HA is still liver biopsy. In our case, we decided to proceed to surgery mainly due to preoperative diagnostic uncertainty and acute symptomatology.

In this report, we present a case of a young female patient with co-existence of FNH and HA of the liver without any previous exogenous administration of oral contraceptives or any other known risk factors predisposing to these liver lesions. This fact, together with the absence of typical radiological characteristics, could imply a common pathway in the pathogenesis of these two benign liver lesions or the presence of an intermediate form with interesting radiological, molecular or pathological features. The uncertainty in diagnosis and acuteness of presenting symptoms were established criteria for prompt surgical management. However, in cases of diagnosed benign tumors, surgery should be performed only when tumors are symptomatic or have a risk of complications such as hemorrhage, rupture or malignant potential.