INTRODUCTION

Primary sarcoma of the liver is a rare entity, representing < 1% of primary hepatic malignancies[1]. Malignancies of vascular differentiation, such as angiosarcomas and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas, are the most common of these tumors. However, other types of sarcomas, such as leiomyosarcomas, embryonal sarcomas, and fibrosarcomas, may arise in the liver, despite being exceedingly rare[2].

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), also known as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, is the most common type of sarcoma seen in adults aged at least 50 years[3]. MFH occurs primarily as a mass on the extremities; the involvement of the retroperitoneum is relatively unusual and the presence in a visceral organ is extremely rare. Like other types of primary hepatic sarcoma, primary hepatic MFH, initially described in 1985[4,5], is very rare, with only 38 patients described to date in the English language literature. However, hepatic MFH has not been reported to be associated with advanced liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We describe here a liver cirrhosis patient who developed synchronous MFH and HCC in liver and we review the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old male was admitted to our hospital for treatment of a newly developed mass in his liver. He had a history of liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class A) due to hepatitis B virus identified 20 years earlier and had taken lamivudine 100 mg/d for 2 years. Two years earlier, he had undergone transarterial chemoembolization for HCC in segment IV detected by dynamic magnetic resonance images. Follow-up imaging, including a computed tomography (CT) scan 4 mo earlier, showed no evidence of tumor recurrence. He had no other significant medical history on follow-up.

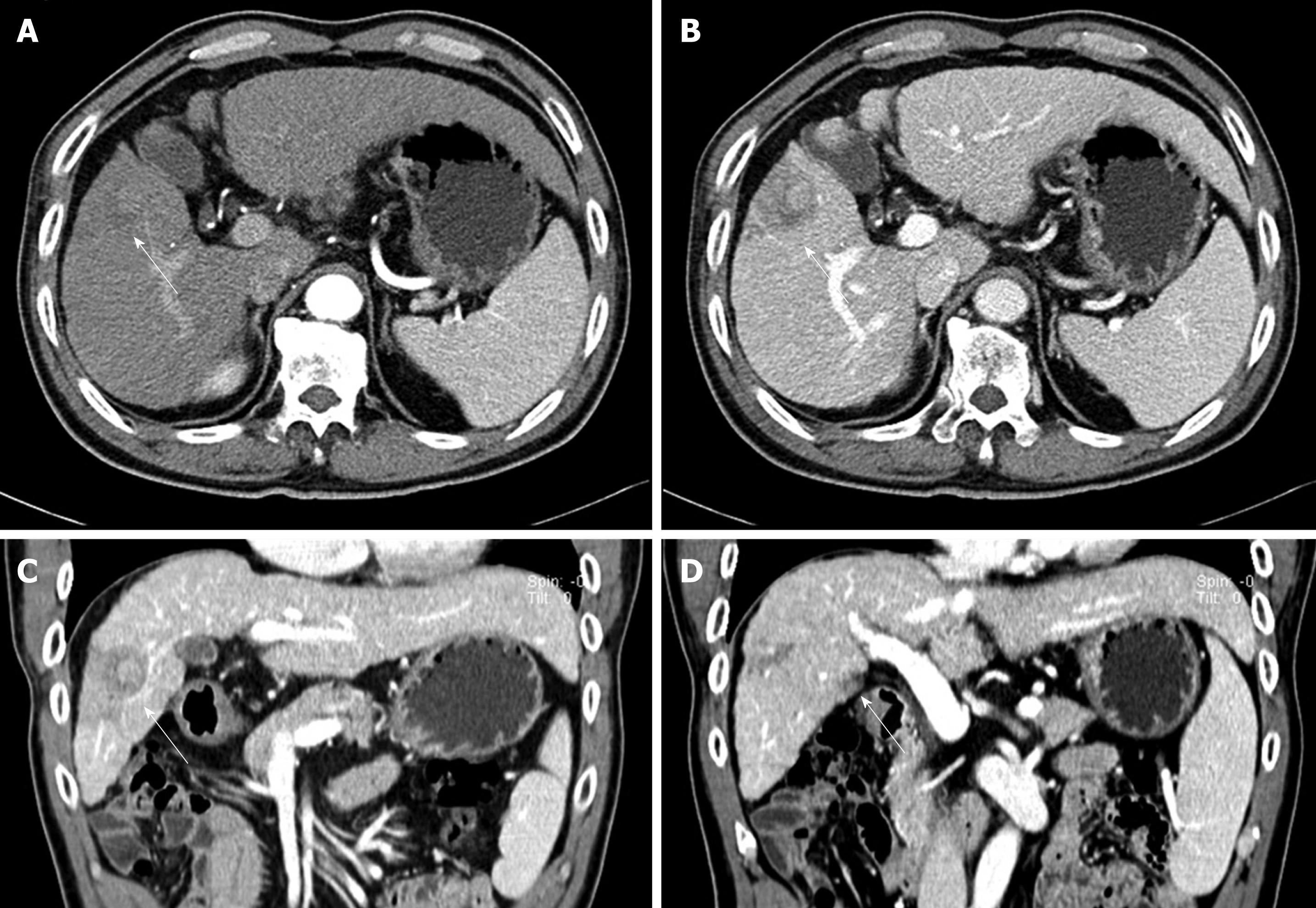

At presentation, he had no symptoms or abnormal physical signs. He was serologically positive for HBsAg but had no other significant laboratory abnormality, including serum transaminase, serum bilirubin and serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) (0.7 ng/mL, normal range 0.00-8.10 ng/mL) concentrations. A CT scan showed an ill-defined, heterogeneous, low-attenuated lesion measuring 4 cm in diameter in the right anterior segment of his liver (Figure 1A-C). This lesion had irregular geographical margins with no bulge onto the hepatic capsule. It was not well enhanced in the late arterial phase or portal venous phase. A second small ill-defined, low-attenuated lesion measuring 1.5 cm was also observed in segment V; this lesion had a similar enhancing pattern as the main mass (Figure 1D). There were no other significant lesions in his abdominal cavity. Based on a clinicoradiological diagnosis of infiltrating HCC, we performed a right anterior segmentectomy.

Figure 1 Computed tomography scan results.

A: An ill-defined, low-attenuated lesion was observed in the right anterior segment on late arterial phase image (arrow); B: The lesion was more clearly seen as a low-attenuated, poorly enhanced lesion in the portal phase. Central high-attenuated portion was observed; C: Coronal reformat image in the portal phase, showing the low-attenuated lesion pushing against the segmental portal vein, resulting in its narrowing (arrow); D: Another coronal reformat image in the portal phase, showing a low-attenuated, poorly enhanced lesion in segment V (arrowhead).

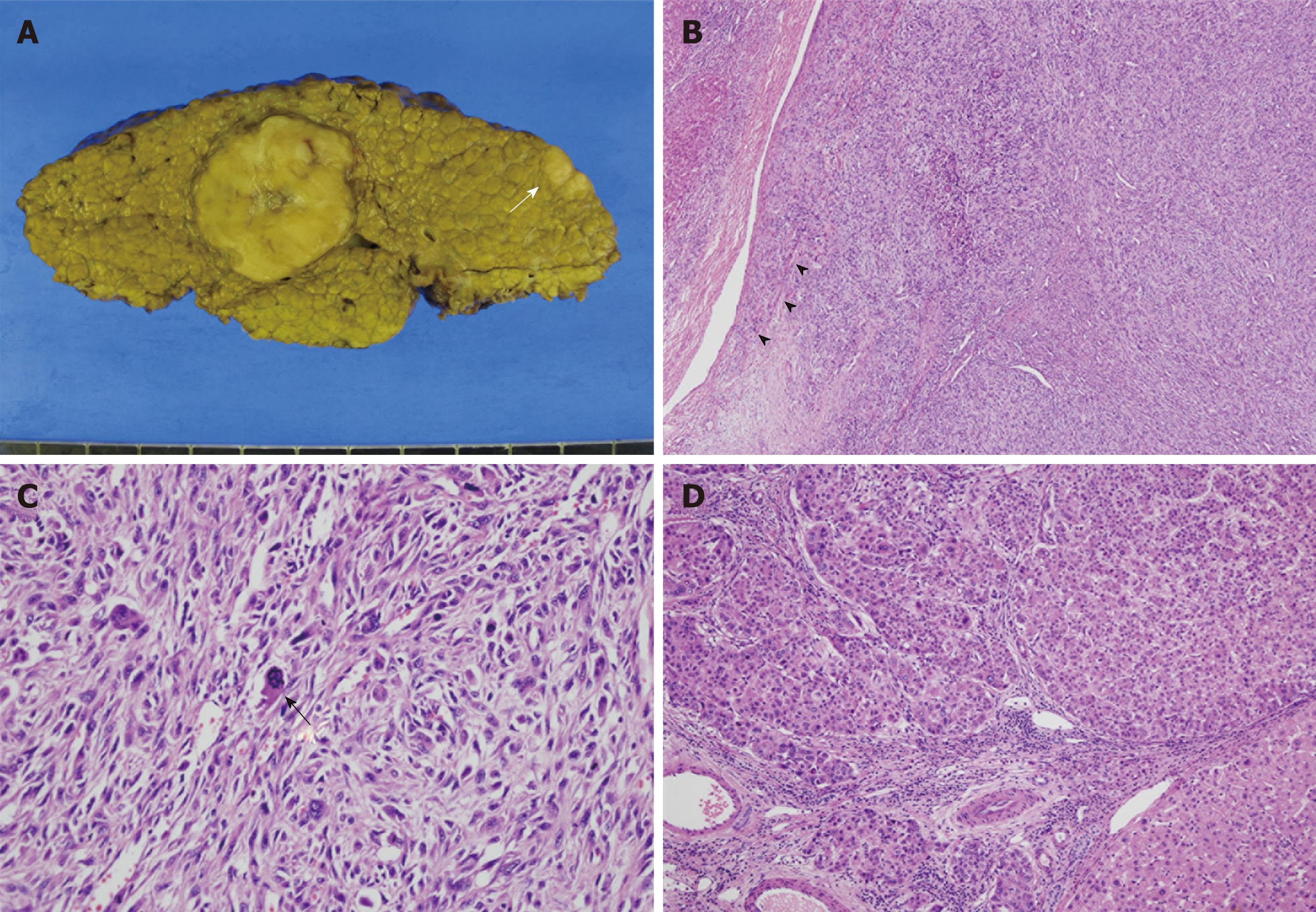

Macroscopically, we observed a relatively well demarcated ovoid mass, measuring 3.8 cm × 3.0 cm × 3.0 cm, on a background of cirrhosis. The mass had yellowish-white color, rubbery consistency and lobulated contour with central tumor necrosis. The lesion was confined to the resected hepatic parenchyma. The second nodule measured 1.4 cm × 1.1 cm × 0.6 cm. Both lesions correlated with the low-attenuated lesions seen in the preoperative CT scan (Figure 2A).

Figure 2 Histopathological findings of the tumors.

A: Gross photography of the resected specimen, showing a large round lobulated mass and a smaller oval-shaped mass (white arrow). Typical multinodular cirrhotic change in background liver was evident; B: Photomicrography of the large round mass, consisting of closely packed spindle cells forming a storiform pattern. Infiltration into the segmental portal vein was also observed (arrowheads) (HE, × 40); C: High power examination, showing pleomorphic spindle cells with bizarre-shaped giant cells, along with numerous mitoses with atypical figures (black arrow) (HE, × 200); D: Photomicrography of the small oval-shaped mass showing polygonal epithelial cells forming trabeculae and round cell nests, consistent with a conventional HCC (HE, × 100).

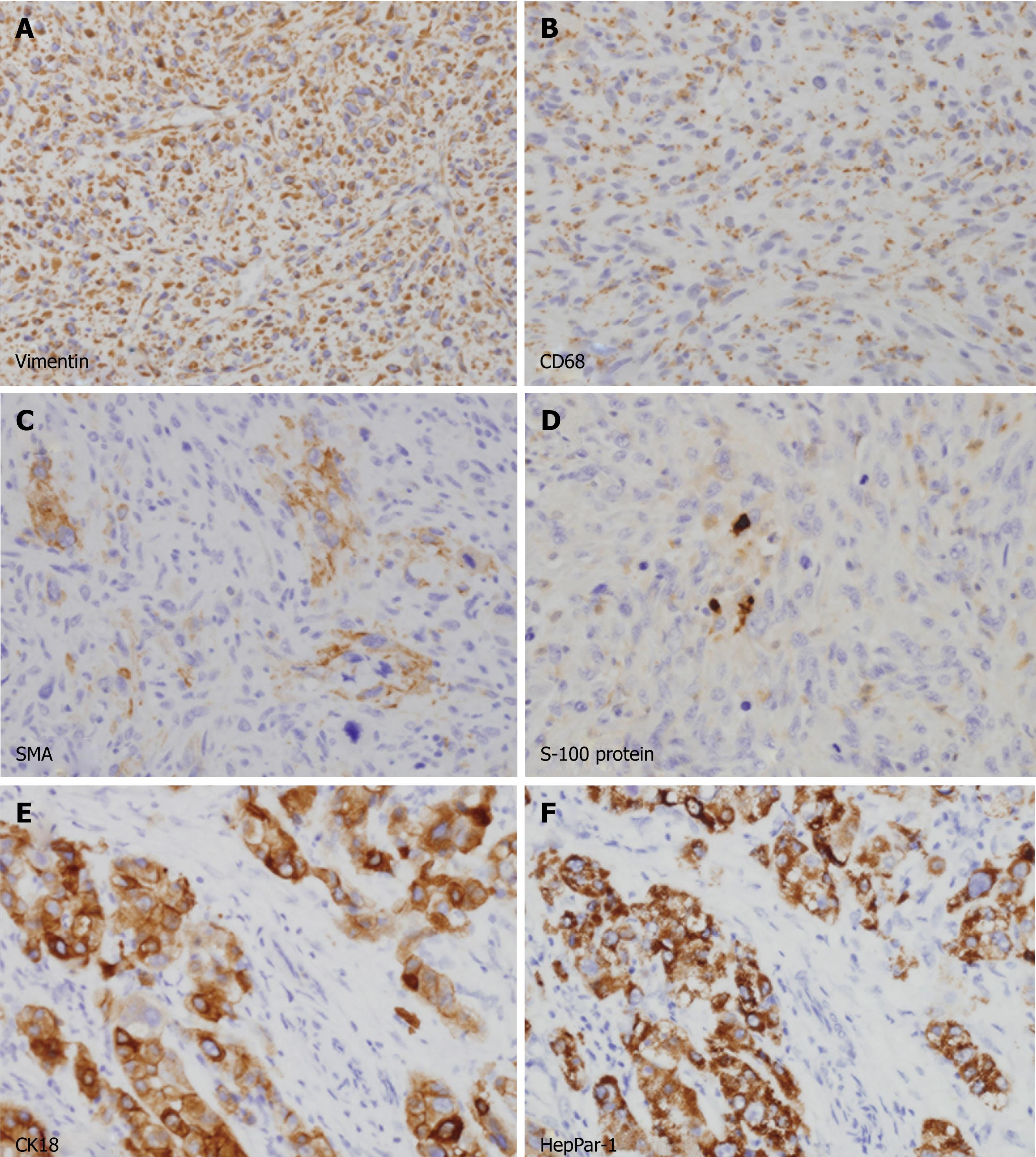

Microscopic examination revealed that the large ovoid mass was totally composed of spindle cells showing fascicular and storiform growth patterns embedded in collagenous background (Figure 2B). The nuclei of the tumor cells were fairly pleomorphic with brisk mitotic figures (more than 20 mitoses in 10 high-power fields). Abnormal mitotic figures and bizarre giant cells were frequently found (Figure 2C). On immunohistochemical stainings, the spindle cells expressed vimentin and CD68 in their cytoplasm (Figure 3A and B) but they did not react with antibodies to AFP, hepatocyte paraffin-1 antigen (HepPar-1), cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, 7 and 18) and endothelial markers (CD31 and CD34). Some of the tumor cells showed weak positive staining for α-smooth muscle actin (Figure 3C) but were negative for desmin and myogenic differentiation-1 (MyoD1). A small number of tumor cells were positive for S-100 protein (Figure 3D). The final pathological diagnosis for the large mass was pleomorphic MFH.

Figure 3 Immunohistochemical analyses of the tumors.

A-D: Spindle cells in the large mass were diffusely immunopositive for vimentin (A) and CD68 (B) in their cytoplasm. A few cells (less than 5%) were also positive for α-smooth muscle actin (C) and S-100 protein (D). All cells were negative for cytokeratins, hepatocyte paraffin-1 antigen (HepPar-1), desmin and myogenic differentiation-1, excluding cells of epithelial and myogenic differentiation (not shown); E, F: Polygonal cells in small mass were strongly immunopositive for cytokeratin 18 (E) and HepPar-1 (F), consistent with a typical hepatocellular carcinoma.

Contrary to the large mass, the small nodule was composed of cords or nests of polygonal epithelial cells showing mixed eosinophilic granular and clear cytoplasm (Figure 2D). Some of these cells had enlarged and pleomorphic nuclei but most had uniform round nuclei. Most of these tumor cells were positively stained for cytokeratin 18 and HepPar-1, indicating hepatocytic differentiation (Figure 3E and F). The final pathological diagnosis for the small nodule was HCC.

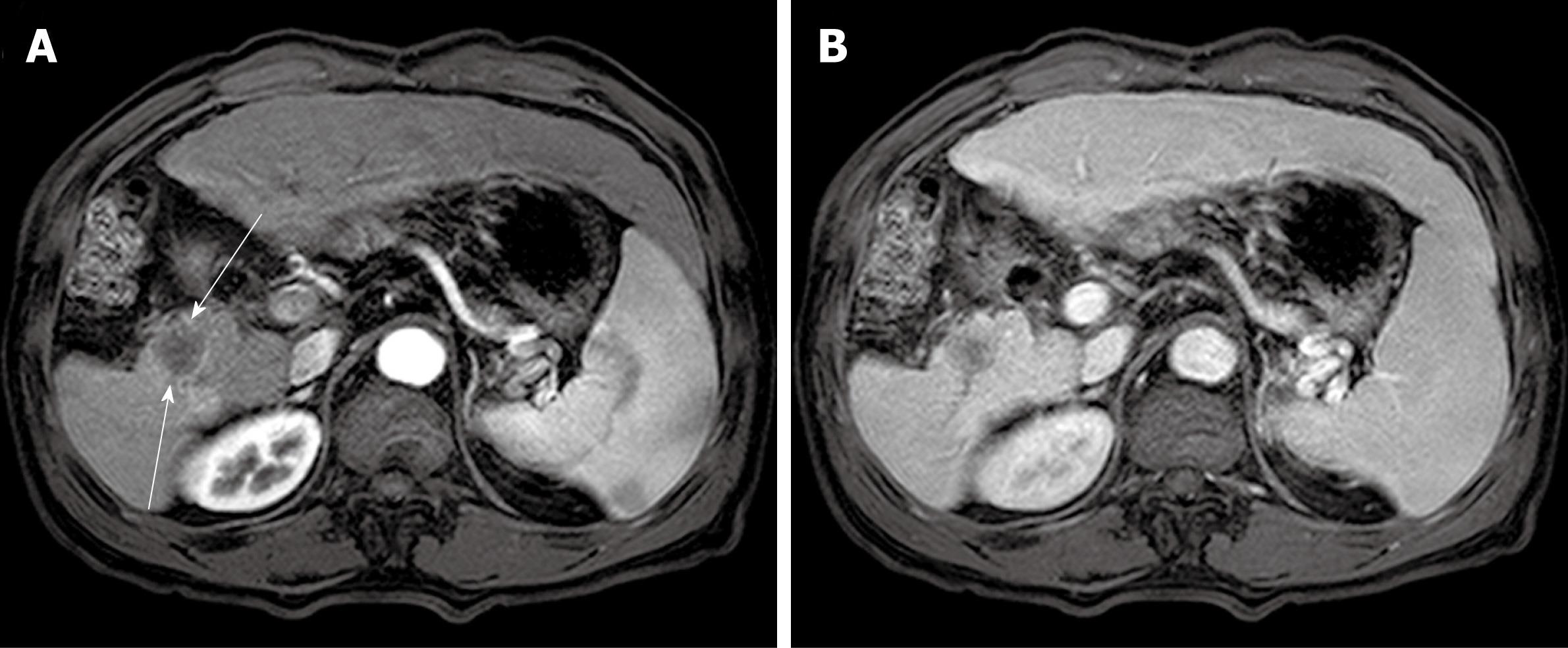

The patient recovered well and was discharged 16 d after surgery. The simple X-ray for both upper and lower extremities and additional chest CT scan showed no abnormal findings, confirming that the sarcoma had originated from the liver. We could not find any evidence of recurrence during the post-operative follow-up of 21 mo. However, a low-attenuated round mass had appeared on resection margin of right posterior segment on abdominal CT scan at that time. Although histological confirmation was not tried, similar contrast enhancement pattern with that of resected MFH on the dynamic image study was suggestive of the recurrence of MFH (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4 Computed tomography scan at follow-up of twenty-one months.

A: A well demarcated low-attenuated round mass was newly found at the resection margin of right posterior segment (slender arrows). This mass was not significantly enhanced in late arterial phase; B: This mass was also not well enhanced at portal phase, which is similar pattern with the previous malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Pleomorphic MFH, regarded as the most common soft tissue sarcoma in adults, was formerly defined as pleomorphic malignant spindle cell neoplasms showing fibroblastic and facultative histiocytic differentiation. However, recent advances in ultrastructural and immunohistochemical techniques have shown that several pleomorphic sarcomas with definite lines of differentiation may share these morphological characteristics[6,7]. According to the World Health Organization classification of soft tissue sarcomas, pleomorphic MFH is defined as pleomorphic spindle cell tumors with unclear lines of differentiation[8].

The clinicopathological criteria for primary hepatic MFH include: (1) solitary or multifocal hepatic tumors without evidence of primary lesions in other parts of the body; (2) lesions histologically compatible with the spectrum of soft tissue MFH; (3) immunohistochemical evidence of mesenchymal differentiation, with < 5% of tumor cells showing any well-defined line of derivation; and (4) the presence of fibroblast-like, histiocyte-like, fibrohistiocytic or undifferentiated cells without evidence of any other well-differentiated cell type by electron microscopy[9]. Our patient presented with no evidence of a primary tumor except in the liver. The pleomorphic spindle cells forming a storiform pattern showed diffuse positive staining for vimentin but were negative for cytokeratins, AFP and HepPar-1, suggesting a true mesenchymal tumor. Moreover, additional immunohistochemical staining showed no significant expression of antigens specifying a lineage of differentiation; although α-smooth muscle actin was focally expressed, desmin and MyoD1 were not significantly expressed and only a small population of tumor cells (< 5%) showed faint expression of S-100 protein. Extensive tissue sampling showed no evidence of a relatively differentiated sarcomatous or carcinomatous focus. Although electron microscopy was not performed, these clinicopathological features were sufficient for a diagnosis of primary hepatic MFH.

We found that the cytoplasm of tumor cells was positive for CD68 in a granular pattern. MFH has been reported to express histiocytic markers, such as CD68, α-1-antitrypsin, α-1-antichymotrypsin and lysozymes[10]. Similar findings have been reported in cases of primary hepatic MFH[9]. Although MFH does not originate from histiocytes[11] and although malignant neoplasms other than MFH may express histiocytic markers[12], positive immunohistochemical staining for histiocytic markers in the absence of other markers for specific lineages raise the possibility of MFH in primary hepatic spindle cell tumors. To our knowledge, our case is the first described case with primary hepatic MFH arising in a cirrhotic liver. Primary hepatic MFH has been reported in three patients with viral hepatitis[13-15] but cirrhotic changes in the remaining hepatic parenchyma were not described in these patients. Thus, in contrast to common belief, hepatic MFH should also be included in the differential diagnosis of liver mass in patients with liver cirrhosis, especially when it is radiologically unusual for HCC.

Primary hepatic MFH may be indistinguishable from other hepatic malignancies, especially in a small biopsy specimen. Nevertheless, although it is extremely rare, the preoperative and/or postoperative diagnosis of hepatic MFH may be necessary in clinical practice. Sarcomatoid HCC is reported to be a slightly worse prognosis than hepatic MFH (23% vs 33% of 2-year survival rate) in distinct small collective studies[9,16]. Furthermore, in contrast to HCC, there is a report that chemoembolization therapy is ineffective in hepatic MFH[17], raising the need for the preoperative diagnosis. However, case reports and collective studies have failed to delineate the common radiological findings of hepatic MFH[18]. For example, our case showed liver cirrhosis and portal vein invasion, the findings favoring HCC over true sarcomas[16,19]. Furthermore, the diagnosis of hepatic MFH cannot be easily rendered by biopsy because the well-differentiated HCC component, necessary for the diagnosis of sarcomatoid HCC, might be present in another portion of tumor that is not examined. Currently, thorough microscopic examination of resected specimen and ancillary immunohistochemical stainings are requisite for the diagnosis of hepatic MFH.

In addition to hepatic MFH, we simultaneously observed a second tumor in this patient, a HCC. To date, there are only three reports of the concurrent development of hepatic sarcoma and HCC in three autopsy cases in Japan but their specific differentiation was not immunohistochemically confirmed[20-22]. To our knowledge, our case is also the first showing synchronous development of hepatic MFH and HCC. Owing to their similarity on CT scans, these two lesions were considered intrahepatic metastases from a large hepatic tumor but their histological features differed. Patients presenting with several liver masses without any significant evidence of extrahepatic primary focus should be suspected of having multiple primary hepatic neoplasms, even though this situation is rare.

In conclusion, primary hepatic MFH may appear in patients with liver cirrhosis and HCC may develop simultaneously. Even in patients with viral hepatitis and cirrhosis, thorough tissue sampling and intensive immunohistochemical analyses should be mandatory to differentiate primary hepatic MFH from other primary hepatic sarcomas and, especially, sarcomatoid HCC.

Peer reviewers: Frank Tacke, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine III,University Hospital Aachen, Pauwelsstr. 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany; Radha Krishan Dhiman, Radha K Dhiman, MD, DM, FACG, Professor, Department of Hepatology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India; Hong-Zhi Xu, PhD, MD, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Shriners Burn Hospital at Boston, 51 Blossom Street, Boston, MA 02148, United States

S- Editor Zhang SJ L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM