Revised: January 14, 2010

Accepted: January 21, 2010

Published online: January 27, 2010

A 84-year-old man with a surgical history of subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer was transferred to our department because of a disorder of consciousness. Septic shock due to obstructive suppurative cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis was diagnosed. Anemia was also present, and upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy revealed blood emerging from the Papilla of Vater. The cause of the anemia was identified as haemobilia. Angiography showed a small aneurysm over the artery on segment 3 (A3). The cause of the haemobilia was suspected to be the bleeding into the biliary tree from this aneurysm. Because the patient’s general condition was poor, minimally invasive therapy was needed. Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) was selected initally. Later, lateral sectionectomy was performed in order to remove the aneurysm on A3. No surgical complication occurred and, after surgery, no haemobilia was identified. In conclusion, a two-stage treatment, namely, surgery following TAE, is recommended for patients in a physically poor condition who have haemobilia due to intrahepatic aneurysm.

- Citation: Takeda K, Tanaka K, Endo I, Togo S, Shimada H. Two-stage treatment of an unusual haemobilia caused by intrahepatic pseudoaneurysm. World J Hepatol 2010; 2(1): 52-54

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v2/i1/52.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v2.i1.52

Bleeding into the biliary tree is a rare cause of gastro-intestinal hemorrhage[1]. The majority of patients with hepatic artery aneurysms are asymptomatic[2] but once an aneurysm ruptures, haemobilia becomes a potentially life-threatening complication. Therefore, early diagnosis and certain hemostasis are essential. Furthermore, in patients in a poor physical condition or in elderly patients, minimally invasive therapy should be performed. In this report, we described a case of haemobilia resulting from severe obstructive suppurative cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis. Complete hemostasis was achieved by surgical treatment following transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE).

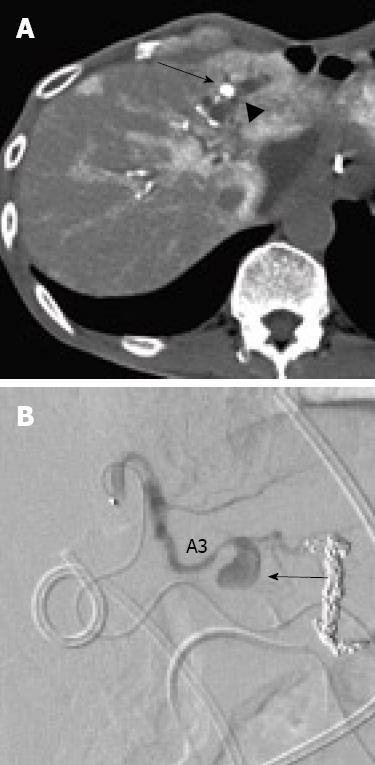

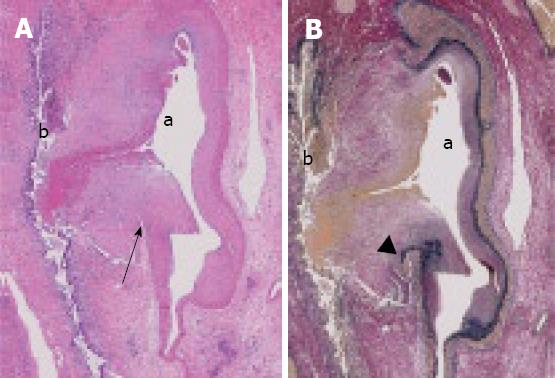

A 84-year-old-man with a surgical history of subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer was transferred to our department because of a disorder of consciousness. He had a fever of 39.5 degrees, yellowish conjunctivae and a blood pressure of 50/20 mmHg. Laboratory data on admission were as follows: Alanine/aspartate aminotransferase, 315/174 IU/L (respectively); total bilirubin, 4.8 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 3.2 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 739 IU/L; C-reactive protein, 24.1 mg/dL; white blood cells, 1000 /μL; platelets, 0.9 × 104/μL; prothrombin time INR, 1.39. Septic shock due to severe infection accompanied by hepatobiliary dysfunction was diagnosed. The laboratory data also showed a decreased level of hemoglobin (7.1 g/dL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an enlarged gallbladder and a dilated common bile duct. Emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed a solitary filling defect which was 12 mm in diameter (Figure 1). Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Clostridium species were detected both in both blood and bile. Therefore, the pathogenesis was considered to be obstructive suppurative cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis. After intensive conservative therapy including bile drainage which enabled the patient to recover from septic shock, a choledocholith was removed. During this process, bleeding from the Papilla of Vater was detected by upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy, enabling the cause of the anemia to be identified as haemobilia. Arterial phase CT revealed a high-density area 1 cm in diameter in the lateral segment of the artery that protruded into the intrahepatic duct (Figure 2A). Angiography showed a small aneurysm over the A3 segment, which was the second branch of the left hepatic artery (Figure 2B). These findings suggested that the haemobilia resulted from the bleeding into the biliary tree from this aneurysm. Because of the patient’s advanced age and because Onodera’s prognostic nutritional index[3] was extremely poor (20.2), we planned the two-stage treatment in order to minimize invasiveness. Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) was performed first and,after recovery of the patient’s nutritional status, this was followed by hepatectomy in order to remove the aneurysmal intrahepatic artery. Because intermittent haemobilia persisted and the recovery of the patient’s general condition waa slow, TAE was required 3 times. However, no massive biliary bleeding appeared, and the patient’s nutritional status gradually improved during this period. Finally, lateral sectionectomy was performed safely. Histological findings indicated that the intrahepatic artery had ruptured into the intrahepatic bile duct. The inner membrane, the elastic laminae, and the tunica media of the artery were not detected at the site of rupture (Figure 3), and so rupture of an arterial pseudoaneurysm was diagnosed. In the 12 mo after surgical treatment, the patient has been attending our hospital as an outpatient, and no further anemia has come to light.

Haemobilia is the phenomenon of bleeding into the biliary tree, and is an unusual cause of obscure upper abdominal bleeding[4]. It is usually due to atherosclerotic aneurysm, trauma, pseudoaneurysm, or vascular anomalies[4]. In this case, choledocholithiasis in the common bile duct and a pseudoaneurysm in the liver were present. The pathogenesis in this case was probably infiltration of the severe inflammatory reaction in the intrahepatic bile duct into the liver parenchyma because of choledocholithiasis, resulting in erosion of the wall of the hepatic artery. This was an unusual etiology, although the patient was 84 years old and histopathologic examination revealed evidence of severe arteriosclerosis. The walls of the arteries were fragile and a pseudoaneurysm was formed as a result[5]. The majority of patients with hepatic artery aneurysms are asymptomatic[2]. However, once such an aneurysm ruptures, haemobilia, which is potentially life-threatening, complicates the patient’s condition. Therefore, all cases of intrahepatic aneurysm should be considered for immediate treatment[2], TAE being the accepted treatment of choice[1,2]. The hepatic artery should be embolized at both the proximal and the distal sides of the aneurysm. This technique that is difficult when the aneurysm is peripheral to the second branch, and normal flow in the portal vein or reflux in the multiple collateral pathways of the artery may appear through sinusoidal lesions[5], and intermittent haemobilia continues. Hepatectomy should be considered at the same time as TAE. In this patient, because of an advanced age and poor nutritional status, we planned a two-stage treatment; TAE first, followed by hepatectomy. After 3 repetitions of TAE, there was no massive biliary bleeding and the patient’s status improved gradually, allowing surgical treatment to be performed safely. Even when the aneurysm is located on branches of the hepatic artery beyond the second, minimally invasive TAE should be performed first, although for hemostasis, TAE alone may be insufficient. In such cases, after improvement in the patient’s condition following TAE, surgery is indispensable as a radical treatment.

In conclusion, we have reported an unusual case in which haemobilia resulted from the rupture of an intrahepatic pseudoaneurysm resulting from severe cholangitis. When the aneurysm is located distal to the second branch of the hepatic artery and the patient is of advanced age or in poor general condition, two-stage treatment comprising TAE and surgery should be performed.

| 1. | Siablis D, Papathanassiou ZG, Karnabatidis D, Christeas N, Vagianos C. Hemobilia secondary to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: an unusual complication of bile leakage in a patient with a history of a resected IIIb Klatskin tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5229-5231. |

| 2. | O'Driscoll D, Olliff SP, Olliff JF. Hepatic artery aneurysm. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1018-1025. |

| 3. | Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients]. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:1001-5. |

| 4. | Liu TT, Hou MC, Lin HC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Life-threatening hemobilia caused by hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a rare complication of chronic cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2883-2884. |

| 5. | Akatsu T, Hayashi S, Egawa T, Doi M, Nagashima A, Kitano M, Yamane T, Yoshii H, Kitajima M. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis that ruptured into the gallbladder. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:900-903. |

Peer reviewer: Pierluigi Toniutto, Professor, Medical Liver Transplant Unit, Internal Medicine, University of Udine, Piazzale S.M. della Misericordia 1, Udine 33100, Iyaly