Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.116475

Revised: December 16, 2025

Accepted: January 5, 2026

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 92 Days and 18.4 Hours

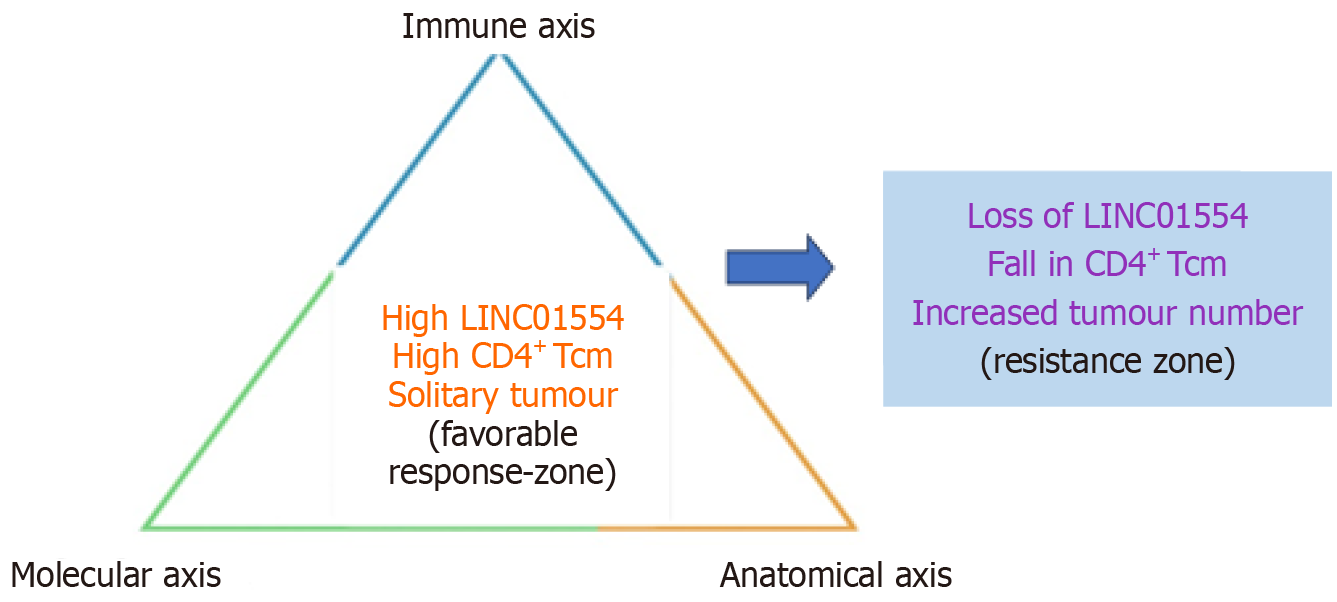

In this editorial, we comment on the article by Wang et al, which investigates molecular and immune biomarkers predictive of response to sintilimab plus lenvatinib in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Yet, despite remarkable progress with immune-checkpoint and anti-angiogenic combinations, the biological heterogeneity of HCC continues to limit durable responses and individualized care. By integrating high-resolution transcriptomic, exomic, and immune-cell-profiling data, Wang et al identified a coherent triad - elevated LINC01554 expression, enrichment of CD4+ central-memory T cells, and solitary-tumour morphology - that independently predicted prolonged pro

Core Tip: Hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma exemplifies the complexity of inflammation-driven oncogenesis. The integration of molecular and immune biomarkers enables a more precise prediction of therapeutic response. Emerging multiomic evidence identifies a triad of high LINC01554 expression, increased CD4+ central memory T cells, and solitary tumour morphology that signifies restrained oncogenic signalling, preserved immune competence, and limited clonal heterogeneity. Recognition of this molecular-immune-anatomical interplay provides a biologic framework for patient selection, response monitoring, and rational sequencing of sintilimab and lenvatinib, representing a decisive step toward scientifically grounded precision hepatology in viral hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Kashiv P, Saxena K, Balwani MR, Kute VB. Integrating molecular and immune biomarkers for precision therapy in hepatitis B: Associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 116475

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/116475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.116475

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with a disproportionate burden in regions where chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is highly prevalent and access to sur

Over the past decade, systemic treatment for unresectable HCC has evolved from single-agent multikinase inhibitors such as sorafenib and lenvatinib to a more complex armamentarium that includes immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and ICI-based combinations[4-6]. Lenvatinib has demonstrated non-inferiority to sorafenib in the first-line setting, while multiple second-line agents - including regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab - have incrementally extended survival in selected populations[6].

Despite these advances, clinical experience and trial data converge on a sobering reality: Responses to ICI-based and tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-based therapies are heterogeneous, and durable benefit is limited to a subset of patients. In most series, objective responses range from 20% to 35%, and even within responders, progression-free survival (PFS) is highly variable[5-7]. This variability reflects the interplay of tumour-intrinsic oncogenic programmes, the immunological composition and organisation of the tumour microenvironment, and classical clinical determinants such as tumour burden, vascular invasion, and liver function[8-11].

The integrative biomarker analysis by Wang et al[1] in the World Journal of Hepatology takes an important step toward rationalising and refining the use of sintilimab plus lenvatinib in HBV-associated HCC through integrative biomarker discovery. Building on a prospective conversion-therapy trial of sintilimab plus lenvatinib in intermediate and locally advanced HCC, which demonstrated encouraging objective responses and a meaningful surgical conversion rate, the authors performed multi-omic profiling of baseline tumour biopsies from patients with predominantly HBV-related disease[1,12].

Using RNA sequencing, immune-cell deconvolution, and whole-exome sequencing, they identified a triad of features - high LINC01554 expression, increased CD4+ central memory T-cell (Tcm) infiltration, and solitary tumour morphology - that independently predicted prolonged PFS under sintilimab-lenvatinib therapy[12-16]. This editorial situates those observations within the broader evolution of precision hepatology, explores their mechanistic plausibility, and proposes a conceptual framework for integrating molecular and immune biomarkers into future clinical decision-making for HBV-associated HCC[17-20].

The rationale for combining programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 blockade with in

Translational analyses from the pivotal trials have further shown that pre-existing T-cell-inflamed phenotypes, high CD8+ T-cell density, and VEGF-related signatures influence the balance of benefit between atezolizumab monotherapy, atezolizumab-bevacizumab, and sorafenib[6,13].

Lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor targeting VEGFR1-3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha, RET, and KIT, possesses both anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties that may po

Sintilimab, a humanised immunoglobulin G4 anti-PD-1 antibody, has similarly shown clinically meaningful activity in multiple tumour types, and its combination with bevacizumab or lenvatinib has yielded improved outcomes in HBV-rich Asian HCC cohorts[7,8].

The phase II trial by Wang et al[1] evaluating sintilimab plus lenvatinib as conversion therapy for intermediate or locally advanced HCC reported an objective response rate of 36% and a disease-control rate exceeding 90%, with a notable proportion of patients successfully converted to resection or ablation. The subsequent integrative biomarker analysis in HBV-associated HCC, now in press, builds directly on this clinical foundation and seeks to explain why some tumours are amenable to durable control and conversion while others progress despite ostensibly similar treatment[15].

In the cohort, Wang et al[1] analysed tumour biopsies from patients with HBV-associated HCC treated with sintilimab plus lenvatinib. All patients had unresectable disease at baseline but were considered potential candidates for conversion to curative therapy[1]. Treatment response was assessed with modified RECIST[13].

The authors undertook a multi-layered analysis: (1) Transcriptomics (RNA sequencing): Differentially expressed genes were identified between responders and non-responders. Among these differentially expressed genes, the long intergenic noncoding RNA LINC01554 and WHRN (whirlin) were significantly associated with longer PFS; (2) Immune microenvironment (xCell-based deconvolution): Responding tumours exhibited higher inferred abundance of B-cell subsets - including pro-B cells, class-switched memory B cells, and plasma cells - whereas the T-cell landscape was more complex, with CD4+ Tcm cells showing a borderline association with improved outcomes in univariable analysis; and (3) Genomic landscape (whole-exome sequencing): The mutational profile included recurrent TP53 and APC alterations typical of HCC. FANCD2 mutations were enriched among non-responders, and CUX1 mutations correlated with shorter PFS, although neither showed robust prognostic significance in external validation datasets.

When clinical, molecular, and immune variables were entered into multivariable Cox regression, three independent predictors of prolonged PFS emerged: (1) Solitary tumour; (2) High LINC01554 expression; and (3) Elevated CD4+ Tcm infiltration. Together, these variables define a multi-dimensional biomarker constellation that aligns with broader pr

Among the identified features, LINC01554 stands out as a particularly compelling molecular anchor for a more favourable tumour phenotype. Long noncoding RNAs have emerged as important regulators of hepatocarcinogenesis, influencing chromatin organisation, transcriptional networks, and key oncogenic pathways. Comprehensive bio

Functionally, LINC01554 overexpression inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion in HCC cell lines, promotes G0/G1 arrest, and attenuates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (increased E-cadherin and ZO-1, decreased N-cadherin and vimentin). In the sintilimab-lenvatinib cohort, high baseline LINC01554 expression was enriched among responders and independently associated with longer PFS[15,20].

A coherent picture thus emerges: Maintenance of LINC01554 expression marks a subset of HBV-associated HCCs in which key oncogenic pathways remain partially restrained, and in which anti-angiogenic blockade plus PD-1 inhibition can more effectively tip the balance toward durable control. Conversely, LINC01554-low tumours likely represent a more plastic, pathway-redundant state capable of rapid adaptation and early escape. These observations do not yet justify clinical testing of LINC01554 as a stand-alone biomarker; however, they provide a compelling rationale for prospective validation and for deeper mechanistic dissection in preclinical models that combine lenvatinib or other VEGF-pathway inhibitors with ICIs[4,5,8,10].

The second pillar of the biomarker triad, CD4+ central memory T cells, highlights the importance of immune contexture in determining response to systemic therapy. Central memory T cells occupy an intermediate state between naïve and effector pools, endowed with proliferative capacity, rapid cytokine production, and the ability to differentiate into cytotoxic or helper subsets upon antigen re-encounter.

In the Wang et al’s analysis[1], higher inferred CD4+ Tcm abundance at baseline independently predicted longer PFS after adjustment for clinical and genomic features. This finding is consistent with broader immuno-oncology data in HCC showing that inflamed tumours - characterised by CD8+ and CD4+ effector and memory cells, activated dendritic cells, and lower regulatory T-cell predominance - tend to respond better to ICI-containing regimens[1,10,17].

Notably, the global immune pattern in the sintilimab-lenvatinib cohort also pointed to an enrichment of B-cell subsets in responders, including pro-B cells, class-switched memory B cells, and plasma cells. This echoes high-impact work in melanoma and other solid tumours demonstrating that tumour-associated B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures are closely linked to ICI responsiveness, with evidence of clonal B-cell expansion, germinal centre formation, and active humoral immunity within tertiary lymphoid structures[18,19].

Taken together, these findings support a model in which baseline immune ecosystem quality - defined by an intact CD4+ memory compartment, supportive B-cell architecture, and limited immunosuppressive skewing - creates per

The third component of the triad - solitary tumour morphology - underscores the continued relevance of conventional clinical and radiological features in a precision-medicine framework. Multifocal tumours, particularly in HBV-related cirrhosis, may arise from multicentric carcinogenesis on a background of field cancerisation and chronic necroinflammation, yielding a more heterogeneous and potentially aggressive disease biology[2,3].

In the sintilimab-lenvatinib biomarker analysis, solitary tumours were significantly associated with longer PFS and remained an independent predictor in multivariable models alongside LINC01554 and CD4+ Tcm. This reinforces the principle that anatomical disease burden and distribution should not be eclipsed by molecular data, but rather integrated into a layered risk model. For conversion therapy in particular, tumour number and distribution have direct implications for resectability, ablation feasibility, and the likelihood of achieving durable locoregional control once systemic therapy has induced regression[4,5,8,14].

The distinctive strength of recent multi-omic analyses in HBV-associated HCC lies not in identifying a single determinant of response but in demonstrating the convergence of three orthogonal biological domains: (1) Tumour-intrinsic transcriptional restraint - characterised by elevated LINC01554 expression and partial suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and Wnt/β-catenin pathways[15,20]; (2) Supportive immune contexture - defined by increased CD4+ central-Tcm infiltration and enrichment of B-cell subsets forming tertiary lymphoid-like structures[10,17-19]; and (3) Favourable anatomical phenotype - represented by solitary-tumour morphology indicating a more tractable disease architecture[2,3,14].

These dimensions can be conceptualised as interacting axes that together determine the “biological temperature” of the tumour and its sensitivity to combined PD-1 and VEGF-pathway inhibition. When all three axes align favourably, the likelihood of durable response and conversion to resection or ablation increases; when one or more are unfavourable, the balance shifts toward resistance. Key features of each biomarker domain and their putative clinical implications are summarised in Table 1, and their inter-relationships are illustrated in Figure 1.

| Domain | Feature/marker | Direction associated with longer progression-free survival | Biologic/mechanistic implication | Putative clinical relevance |

| Molecular (long noncoding RNAs) | High LINC01554 expression | Favourable | Tumour-suppressive activity; restrains Wnt/β-catenin and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathways | Candidate biomarker for selecting patients likely to respond to PD-1/tyrosine kinase inhibitor combinations |

| Immune | High CD4+ central memory T-cell infiltration | Favourable | Preserved adaptive memory enabling sustained immune reactivation after PD-1 blockade | Supports durable anti-tumour immunity and prolonged disease control |

| Immune (B-cell axis) | Enrichment of B-cell subsets (pro-B, class-switched memory, plasma cells) | Observed in responders | Tertiary lymphoid structure-like microenvironment | May augment CD4+/CD8+ T-cell coordination and checkpoint efficacy |

| Genomic | CUX1 mutation | Unfavourable | Transcriptional dysregulation; possible link to genomic instability | Potential prognostic marker of poor outcome; needs independent validation |

| Genomic (DNA repair) | FANCD2 mutation | Enriched in non-responders | Defective DNA repair and replication stress | May signify intrinsic therapy resistance or need for alternative pathway targeting |

| Clinical/anatomical | Solitary tumour morphology | Favourable | Lower clonal heterogeneity and contained microenvironment | Higher likelihood of durable response and successful conversion to resection or ablation |

A structured framework can be developed to integrate molecular and immune biomarkers into therapeutic decision-making for HBV-associated HCC. This approach demonstrates how multidimensional biomarker data can be layered onto established clinical pathways to refine decisions and personalise therapy[9,10].

The findings by Wang et al[1] align with several broader themes in the immuno-oncology of HCC. Integrated analyses from atezolizumab-bevacizumab trials have emphasised that pre-existing T-cell inflamed phenotypes, high programmed death ligand 1 expression, and intratumoural CD8+ T-cell density correlate with improved outcomes on combination therapy, whereas an abundance of regulatory T cells, oncofetal signatures (e.g., glypican 3, alpha fetoprotein), and myeloid inflammation portend inferior benefit[5,10].

HBV-driven HCC often arises in a background of chronic antigen exposure and immune exhaustion, yet can harbour immunologically active niches that are potentially reprogrammable with ICIs and anti-angiogenic agents[2,3,9,10,17].

In this context[10,15], the LINC01554 - CD4+ Tcm - solitary tumour triad can be viewed as a prototype integrated signature for HBV-associated HCC treated with PD-1/TKI combinations[16-20]. Its components are conceptually consistent with three cross-cutting principles: Tumours with preserved tumour-suppressive circuitry and less chaotic signalling are more amenable to durable control.

A resilient and adaptable immune network - especially memory T cells supported by B-cell-rich structures - facilitates sustained responses to checkpoint blockade. Lower anatomical complexity and clonal dispersion enhance both systemic and locoregional treatment success.

HBV itself adds further complexity, given the influence of viral integration, chronic inflammation, and viral antigen expression on both tumour biology and immune surveillance. Any biomarker framework applied to HBV-associated HCC must therefore be interpreted through this aetiological lens.

The immediate implication of the sintilimab-lenvatinib biomarker study is not that clinicians should routinely order LINC01554 or Tcm assays today, but rather that future clinical trials evaluating PD-1/TKI or ICI/anti-VEGF combinations should be designed with integrated biomarker platforms from the outset[4,5,8,10].

Several important caveats must temper interpretation of the biomarker triad: (1) Sample size and single-centre design: The study included 33 patients from a single institution, raising the risk of overfitting and limiting external validity; (2) Retrospective biomarker analysis: Although embedded within a prospective treatment trial, the biomarker work was retrospective, and thresholds were optimised internally rather than pre-specified; and (3) Limited external validation at the integrative level: While individual genes such as LINC01554 correlate with survival in independent datasets, the specific combination of high LINC01554, high CD4+ Tcm, and solitary tumour has not yet been tested prospectively or in other therapeutic contexts[15].

Therefore, the proposed framework should be regarded as hypothesis-generating, offering a conceptual scaffold for future research rather than a ready-to-apply clinical tool. Premature adoption of any one component as a stand-alone decision-maker would be inappropriate.

The study by Wang et al[1] illustrates how multi-omic integration can begin to move HBV-associated HCC from empiric treatment toward biologically guided therapy. High LINC01554 expression, increased CD4+ central Tcm infiltration, and solitary tumour morphology together delineate a subset of patients more likely to achieve durable disease control with sintilimab plus lenvatinib, and more likely to be converted to potentially curative interventions. For clinicians, these data support a stance of cautious optimism: PD-1/TKI combinations can deliver striking outcomes in selected patients, particularly when used with a clear intent to convert to resection or ablation. For translational investigators, they highlight the necessity of embedding robust molecular and immune profiling into future trials, and of viewing HCC not as a homogeneous entity but as a collection of biologically distinct subtypes shaped by viral aetiology, tumour genomics, immune architecture, and clinical anatomy.

| 1. | Wang LJ, Cui Y, Huang LF, Zhang JQ, Zhao TT, Wang HW, Liu M, Jin KM, Wang K, Xing BC. Molecular biomarkers of sintilimab plus lenvatinib in hepatitis-B-virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2025;17:112364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2800] [Cited by in RCA: 4366] [Article Influence: 545.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2184] [Cited by in RCA: 3124] [Article Influence: 446.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 4. | Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, Okusaka T, Kobayashi M, Kumada H, Kaneko S, Pracht M, Mamontov K, Meyer T, Kubota T, Dutcus CE, Saito K, Siegel AB, Dubrovsky L, Mody K, Llovet JM. Phase Ib Study of Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab in Patients With Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2960-2970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 154.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 5324] [Article Influence: 887.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (29)] |

| 6. | Wang L, Wang H, Cui Y, Liu M, Jin K, Xu D, Wang K, Xing B. Sintilimab plus Lenvatinib conversion therapy for intermediate/locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase 2 study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1115109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hoy SM. Sintilimab: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2019;79:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, Lopez C, Dutcus C, Guo M, Saito K, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Ren M, Cheng AL. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4115] [Article Influence: 514.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 9. | Piñero F, Dirchwolf M, Pessôa MG. Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Response Assessment. Cells. 2020;9:1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, Pikarsky E, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 1231] [Article Influence: 307.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 11. | Majewski J, Schwartzentruber J, Lalonde E, Montpetit A, Jabado N. What can exome sequencing do for you? J Med Genet. 2011;48:580-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10137] [Cited by in RCA: 8540] [Article Influence: 502.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3353] [Cited by in RCA: 3440] [Article Influence: 215.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (43)] |

| 14. | Kudo M, Montal R, Finn RS, Castet F, Ueshima K, Nishida N, Haber PK, Hu Y, Chiba Y, Schwartz M, Meyer T, Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Objective Response Predicts Survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Systemic Therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3443-3451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li L, Huang K, Lu Z, Zhao H, Li H, Ye Q, Peng G. Bioinformatics analysis of LINC01554 and its coexpressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2020;44:2185-2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, Fang Q, Huang L. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morita M, Nishida N, Sakai K, Aoki T, Chishina H, Takita M, Ida H, Hagiwara S, Minami Y, Ueshima K, Nishio K, Kobayashi Y, Kakimi K, Kudo M. Immunological Microenvironment Predicts the Survival of the Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Anti-PD-1 Antibody. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:380-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, Thakur R, Yizhak K, Sade-Feldman M, Blando J, Han G, Gopalakrishnan V, Xi Y, Zhao H, Amaria RN, Tawbi HA, Cogdill AP, Liu W, LeBleu VS, Kugeratski FG, Patel S, Davies MA, Hwu P, Lee JE, Gershenwald JE, Lucci A, Arora R, Woodman S, Keung EZ, Gaudreau PO, Reuben A, Spencer CN, Burton EM, Haydu LE, Lazar AJ, Zapassodi R, Hudgens CW, Ledesma DA, Ong S, Bailey M, Warren S, Rao D, Krijgsman O, Rozeman EA, Peeper D, Blank CU, Schumacher TN, Butterfield LH, Zelazowska MA, McBride KM, Kalluri R, Allison J, Petitprez F, Fridman WH, Sautès-Fridman C, Hacohen N, Rezvani K, Sharma P, Tetzlaff MT, Wang L, Wargo JA. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577:549-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 815] [Cited by in RCA: 1954] [Article Influence: 325.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Petitprez F, de Reyniès A, Keung EZ, Chen TW, Sun CM, Calderaro J, Jeng YM, Hsiao LP, Lacroix L, Bougoüin A, Moreira M, Lacroix G, Natario I, Adam J, Lucchesi C, Laizet YH, Toulmonde M, Burgess MA, Bolejack V, Reinke D, Wani KM, Wang WL, Lazar AJ, Roland CL, Wargo JA, Italiano A, Sautès-Fridman C, Tawbi HA, Fridman WH. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature. 2020;577:556-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 1412] [Article Influence: 235.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Monga SP. β-Catenin Signaling and Roles in Liver Homeostasis, Injury, and Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1294-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/