Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.115048

Revised: November 17, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 113 Days and 10 Hours

Sarcopenia and frailty are pervasive, interrelated syndromes in cirrhosis that worsen morbidity, quality of life, transplantation waitlist outcomes, and post-transplant survival. This review synthesized contemporary evidence on defini

Core Tip: Sarcopenia and frailty are under-recognized yet powerful predictors of outcomes in cirrhosis, influencing de

- Citation: Goyal MK, Chowdhary R, Vohra C, Patel M, Kalra S, Mehta M, McNulty R, Goyal K, Vuthaluru AR, Goyal O. Current management strategies for sarcopenia and frailty in cirrhosis: Missing link in transplant candidacy. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 115048

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/115048.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.115048

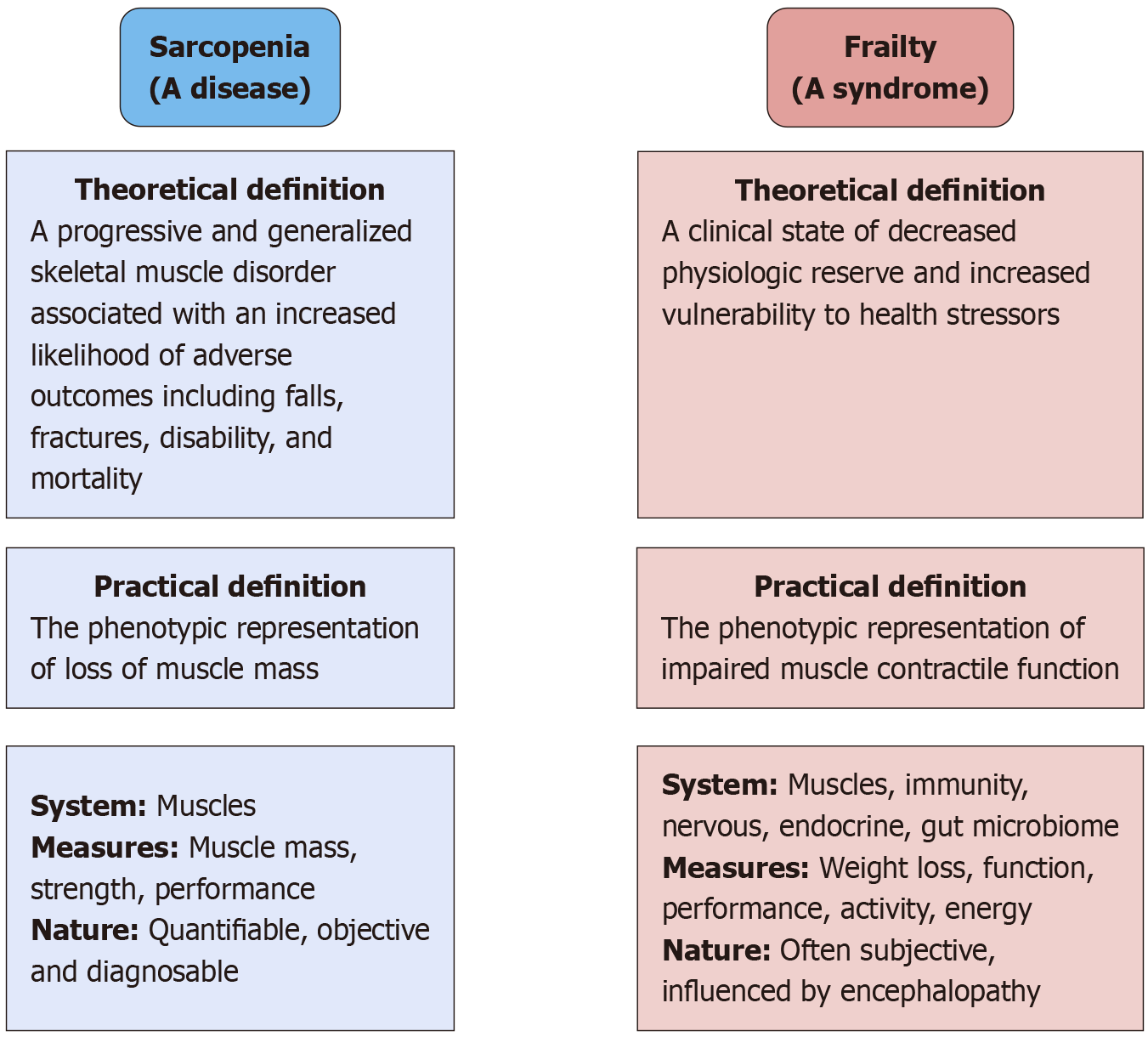

The clinical spectrum of cirrhosis extends beyond the liver pathology. It is a systemic disease that has detrimental effects on other organ systems of the body. Two important clinical factors that can influence mortality and morbidity associated with cirrhosis are sarcopenia and frailty[1]. Rosenberg first coined the term sarcopenia, which is derived from two words: Sarco meaning flesh and penia meaning loss of. On average an individual loses 1% of their muscle every year until the age of 70 and at a rate of 1.5% every year thereafter. Sarcopenia is a generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass and deterioration in its strength and function. Frailty is a broader term characterized by decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors. It is characterized by weakness and fatigue (Figure 1). Frailty is defined as impaired muscle function, and sarcopenia is defined as decreased muscle mass.

The diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia as proposed by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) in 2010 and revised in 2019 are summarized in Table 1. It is not only a measure of muscle mass but also includes cognitive and functional aspects. Sarcopenia and frailty when identified early can predict mor

| Subtype of sarcopenia | EWGSOP 2010 definition | EWGSOP 2019 definition[9] |

| Probable sarcopenia | Reduced mass of muscles | Reduced strength of muscles |

| Sarcopenia | Reduced mass of muscles | Reduced strength of muscles |

| Plus reduced strength of muscles | Plus reduced mass/quantity or function of muscles | |

| Severe sarcopenia | Reduced mass of muscles | Reduced strength |

| Plus reduced strength of muscles | Plus reduced mass/quantity of muscles | |

| Plus reduced function | Plus reduced function | |

| Cutoff | < 30 kg in males, < 20 kg in females plus BMI adapted | < 27 kg in males, < 16 kg in females |

Sarcopenia and frailty are significantly more prevalent in patients with cirrhosis compared with the general population in the same age group[3]. Among patients with cirrhosis the prevalence of sarcopenia ranges from 40% to 70%, and the prevalence of frailty ranges from 18% to 43%[2,4-6]. The range is dependent upon several factors, including the popu

Frailty is prevalent in approximately 20%-50% of patients with cirrhosis. In a recent study frailty defined by the Clin

Sarcopenia was first defined by EWGSOP in 2010 stating that for the diagnosis of sarcopenia both low muscle mass and low muscle function are needed. This dual criterion approach acknowledges that diminished muscle quantity alone (sometimes termed pre-sarcopenia) is insufficient if functional impairment is absent. In 2019 EWGSOP revised the definition incorporating new research that highlighted the paramount importance of muscle strength. The revised consensus adopted low muscle strength as the primary indicator of sarcopenia on the basis that strength better predicts adverse outcomes than muscle mass[9]. In the EWGSOP2 algorithm, probable sarcopenia is identified when low muscle strength is detected, and the diagnosis is then confirmed by evidence of low muscle quantity or quality (e.g., low muscle mass on imaging). An individual who has all three criteria (low strength, low muscle mass/quality, and impaired physical performance, such as slow walking speed or poor chair-stand test) is classified as having severe sarcopenia. This evolution from 2010 to 2019 signifies a shift from viewing sarcopenia as primarily a muscle mass deficit to a broader neuromuscular failure concept with muscle weakness at the forefront[10].

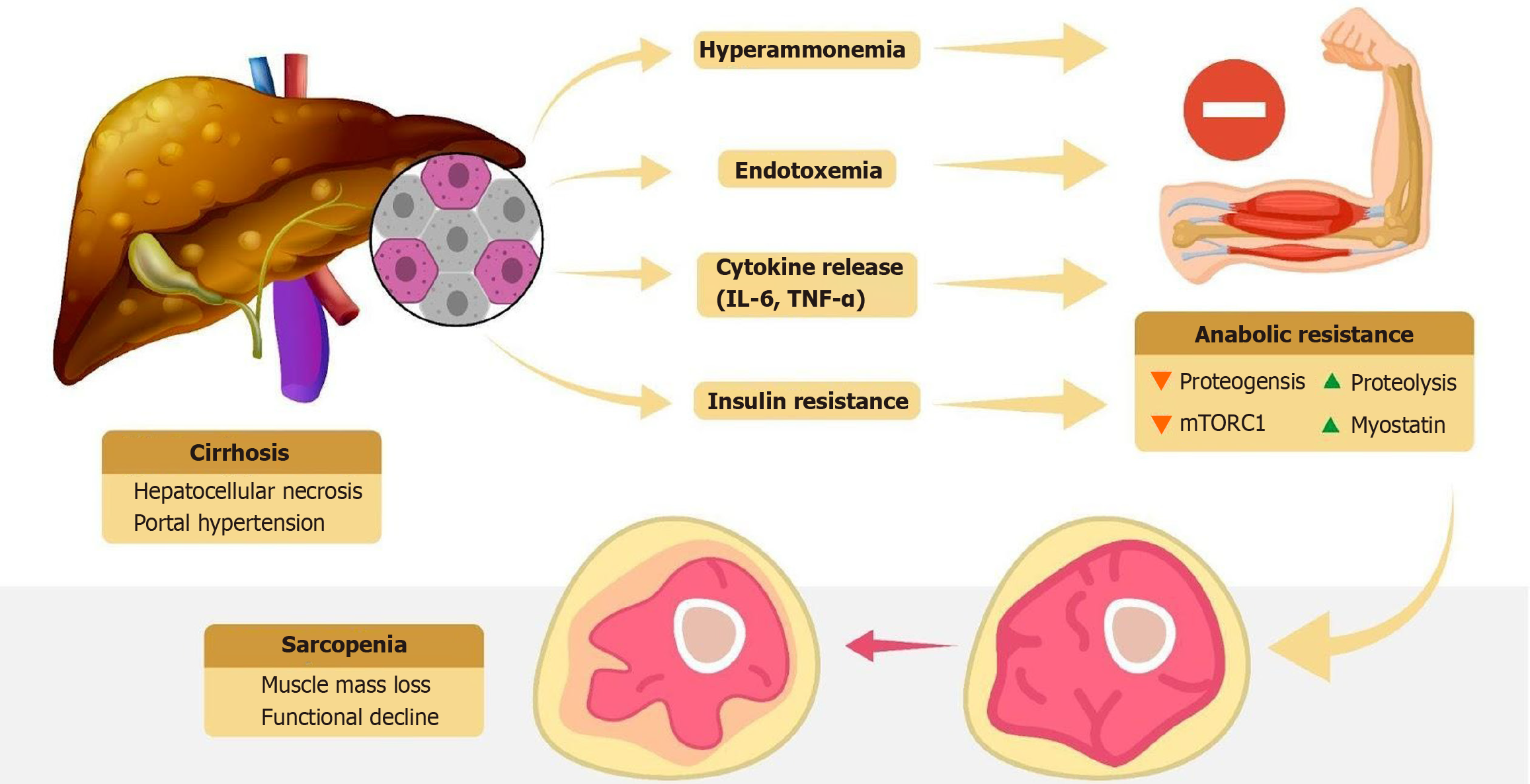

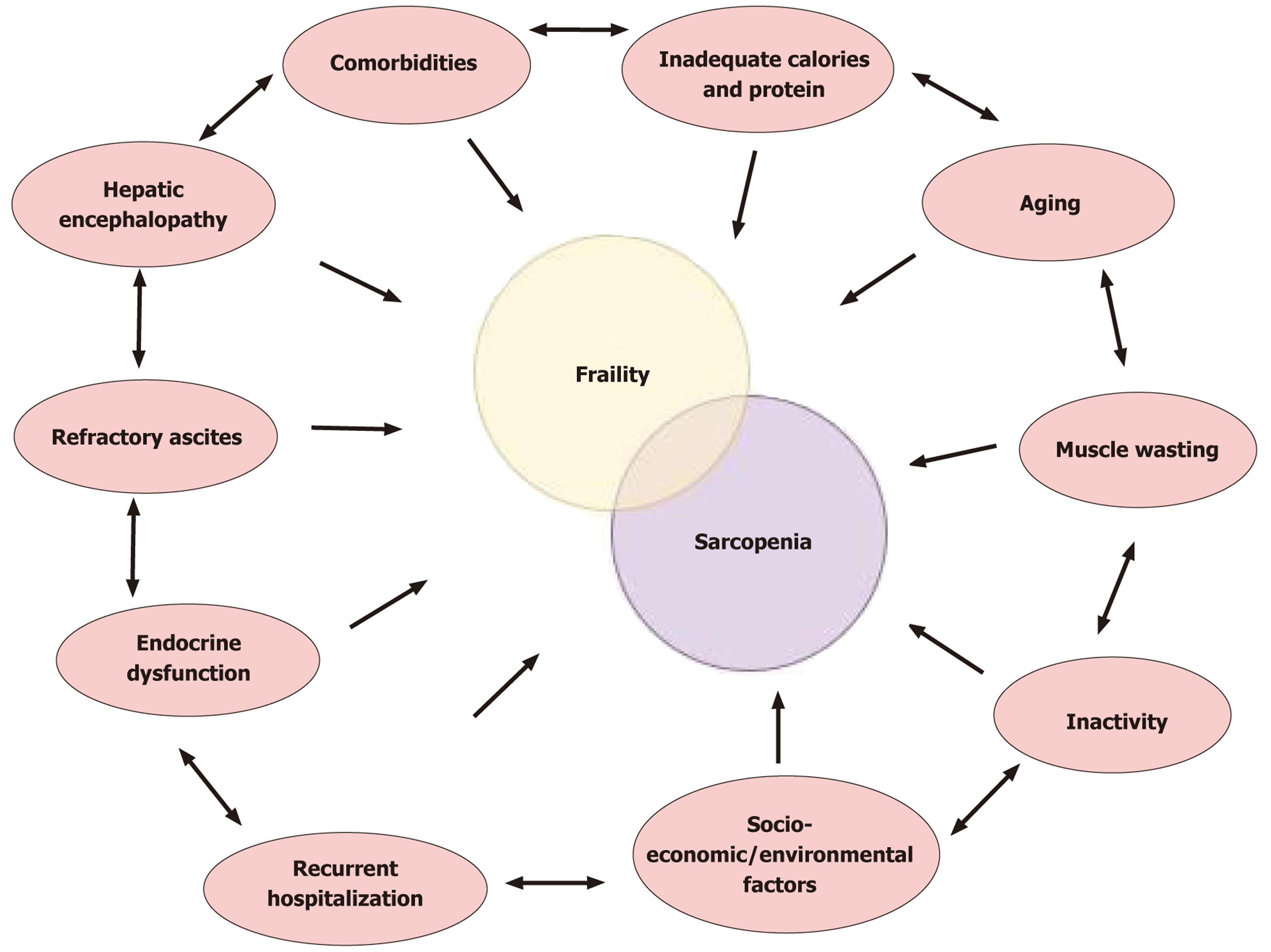

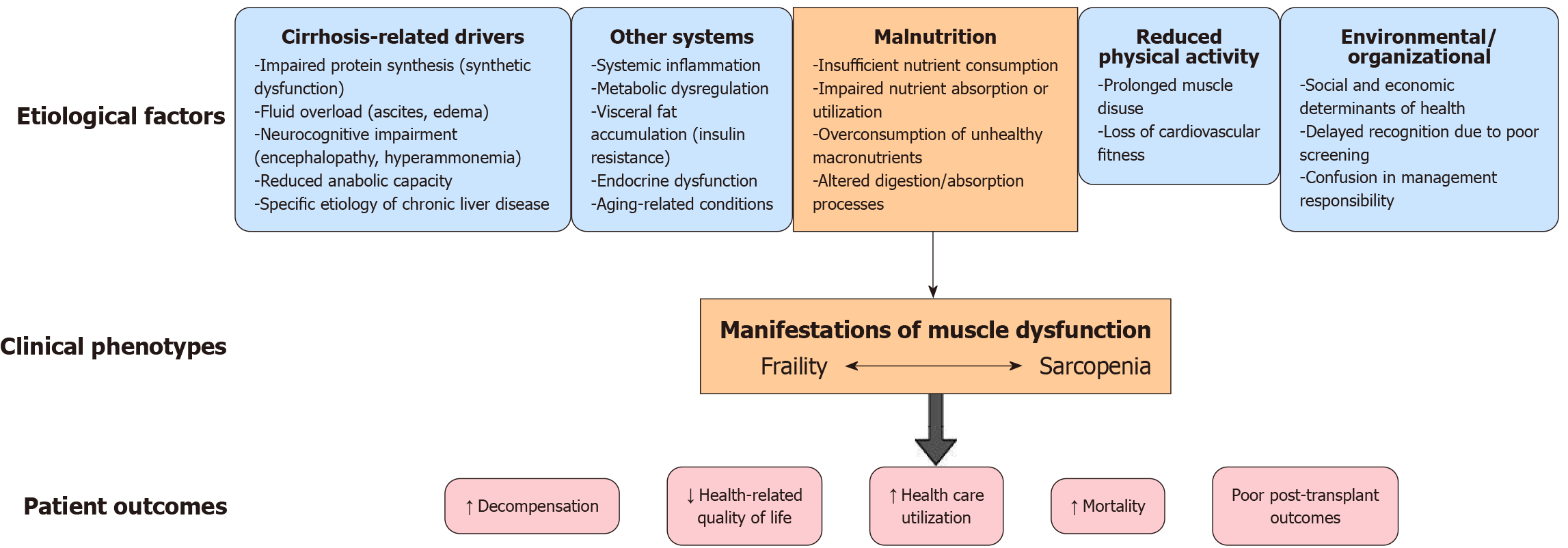

There are multiple factors that contribute to skeletal muscle loss in cirrhosis. These factors include hepatocellular necrosis with cytokine release, danger-associated molecular patterns, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, hyperammonemia, and endotoxemia (Figures 2 and 3). The etiological cause of liver disease may also lead to sarcopenia[11]. A state of anabolic resistance is created in cirrhosis. It is a state in which a less-than-expected increase in proteogenesis and a less-than-expected decrease in proteolysis are found[12,13].

Hyperammonemia is a hallmark of advanced cirrhosis due to impaired hepatic urea cycle function. Ammonia that cannot be detoxified by the liver is shunted to skeletal muscle where it is taken up and amidated to glutamine. This process consumes α-ketoglutarate, an essential Krebs cycle substrate, thereby impairing mitochondrial ATP production in myocytes[14]. The energy deficit and accumulation of toxic ammonia metabolites trigger muscle catabolism. Elevated ammonia levels also induce molecular changes that directly promote muscle loss [e.g., upregulating myostatin (a negative regulator of muscle growth) and activating an integrated stress response (eIF2α phosphorylation) that inhibits protein synthesis][15]. Ribosomal biogenesis decreases due to hyperammonemia and leads to dysfunction in proteostasis[16]. Hyperammonemia also leads to impairment of mitochondrial oxidative function, which is also caused by the effects of ethanol. This impairment is caused by inhibition of electron transport chain components, electron leakage, free radical generation, and oxidative tissue injury[17,18]. In essence ammonia becomes myotoxic in cirrhosis, eroding muscle mass as the body attempts to compensate for liver failure.

Cirrhosis is often accompanied by chronic systemic inflammation (sometimes described as cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction). Elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are catabolic to muscle, activating ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathways and proteolytic transcription factors (e.g., nuclear factor kappa B) while suppressing anabolic signaling[19]. This cytokine milieu leads to increased muscle protein breakdown and reduced synthesis. Oxidative stress further exacerbates muscle damage. In alcohol-related cirrhosis, ethanol metabolism in muscle produces reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing to muscle fiber apoptosis and autophagy. Thus, persistent inflammation and oxidative stress in cirrhosis create a cachectic envi

Cirrhosis commonly disrupts normal endocrine axes that are vital for muscle anabolism. Hypogonadism (low tes

Insulin resistance is another key feature, particularly in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatitis C cirrhosis, and it leads to the so-called anabolic resistance in muscle. Despite high circulating insulin, nutrient uptake and protein synthesis in muscle are blunted. Insulin resistance also contributes to myosteatosis (fat infiltration in muscle), which further weakens muscle quality. Endocrine derangements in cirrhosis, including low anabolic hormones (testosterone, IGF-1) and insulin resistance, tip the balance toward muscle catabolism. Notably, alcoholic liver disease can directly cause hypogonadism and elevated cortisol, compounding these effects. Restoring endocrine function (e.g., testosterone supplementation) is being explored as a strategy to counter sarcopenia in this population[21-23].

Protein-calorie malnutrition is highly prevalent in cirrhosis due to reduced oral intake (from nausea, early satiety due to ascites, dietary restrictions, etc.) and malabsorption (Figure 4). Cirrhosis induces a hypermetabolic state often likened to accelerated starvation in which after even short fasting intervals the body shifts to catabolic metabolism. As hepatic glycogen stores are reduced in cirrhosis, gluconeogenesis is initiated early and amino acids from skeletal muscle are rapidly mobilized to maintain blood glucose[24]. This leads to disproportionate muscle protein breakdown to supply gluconeogenic substrates.

Additionally, chronic liver disease is associated with deficiency of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and other nutrients important for muscle maintenance. Fat malabsorption (in cholestatic disease) and pancreatic insufficiency (in alcoholic liver disease) can further deprive muscles of energy and vitamins (e.g., vitamin D, which is often deficient and contributes to muscle weakness). Overall, undernutrition in cirrhosis deprives muscles of the protein and energy needed for regeneration, and the catabolic metabolism (continuous gluconeogenesis from muscle amino acids) steadily erodes muscle mass. Ensuring adequate protein-caloric intake (1.2-1.5 g/kg protein per day and frequent meals) is therefore a cornerstone of managing sarcopenia in cirrhosis[25,26].

Emerging evidence implicates the gut-liver-muscle axis in cirrhosis-associated sarcopenia. Cirrhosis causes qualitative and quantitative changes in the gut microbiome (dysbiosis) that can affect skeletal muscle via microbial metabolites and bile acids (BAs). Patients with cirrhosis and sarcopenia have been found to harbor distinct gut bacterial profiles and elevated levels of secondary BAs (like deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid) in the circulation[17]. These secondary BAs result from increased bacterial conversion of primary BAs in the gut when dysbiosis is present[18]. High secondary BA levels may directly contribute to muscle wasting. For example deoxycholic acid can activate the TGR5 BA receptor on muscle cells, triggering pathways that favor protein catabolism and energy expenditure[27].

Concurrently, valuable muscle fuels and signaling molecules such as BCAAs (e.g., valine) are found in lower concentrations in patients with sarcopenia, suggesting that an altered microbiome may be consuming or failing to produce key nutrients[28]. In NAFLD/NASH, which often coexists with obesity, gut-derived signals are thought to link steatotic liver and muscle loss. Patients with NAFLD show elevated BA levels inversely correlated with muscle volume[26,29]. Al

A fundamental mechanism underlying muscle atrophy in cirrhosis is an imbalance between protein synthesis and degradation at the cellular level. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a key anabolic signaling cascade that stimulates muscle protein synthesis in response to nutrients and growth factors. In cirrhosis mTOR activity in muscle is often blunted due to factors like reduced amino acid availability (especially BCAAs), insulin/IGF-1 resi

Hyperammonemia also contributes to mTOR inhibition via activation of the GCN2/eIF2α pathway (integrated stress response), which shuts down global protein synthesis. With the mTOR signaling dampened, muscle cannot appropriately ramp up protein synthesis even when nutrients are provided (anabolic resistance). On the flip side catabolic pathways like autophagy (the lysosomal degradation of cellular components) and the ubiquitin-proteasome system are overactive in cirrhosis. Hyperammonemia is a potent trigger of autophagy in skeletal muscle as is chronic alcohol exposure. For instance the toxic metabolite acetaldehyde (from alcohol) has been shown to impair muscle protein synthesis and activate autophagy genes in muscle tissue. Inflammatory mediators (TNF, IL-6) likewise upregulate proteasomal enzymes through nuclear factor kappa B, accelerating the breakdown of myofibrillar proteins. The result of these combined effects is a net loss of muscle protein. Biopsies from patients with sarcopenia and cirrhosis show molecular evidence of increased muscle proteolysis and apoptosis alongside inhibited mTOR/anabolic signaling.

Therapeutically, trials of mTOR-activating agents (e.g., leucine supplements) or autophagy inhibitors in cirrhotic animals have shown some promise in restoring muscle mass. Overall, an imbalance favoring protein degradation (via autophagy-proteasome activation) over synthesis (via mTOR suppression) is a central pathophysiologic feature of sar

Many patients with advanced liver disease experience fatigue, weakness, and frequent hospitalizations that substantially reduce their physical activity levels. Immobility and bedrest lead to disuse atrophy of muscles, compounding the direct metabolic effects of cirrhosis. Even in the outpatient setting, patients with cirrhosis are often sedentary or have limited exercise tolerance. Studies show that low physical activity is an independent risk factor for sarcopenia in cirrhosis. Inactivity removes the normal mechanical stimuli that promote muscle maintenance; without regular muscle contraction and loading, muscle protein synthesis decreases, and atrophy ensues. Bedrest studies in other populations demonstrate that significant muscle loss and functional decline occur within days to weeks of inactivity, a scenario often faced by patients with decompensated cirrhosis during hospitalization. Furthermore, lack of exercise in cirrhosis contributes to a vicious cycle of worsening frailty: Patients become weaker and more prone to falls and hospitalization, causing further inactivity. Notably, exercise interventions in cirrhosis have been shown to improve muscle function and aerobic capacity without precipitating complications, underlining that much of the frailty seen is reversible with activity. Thus, physical inactivity is both a cause and consequence of sarcopenia in liver disease. Combating sedentariness through supervised exercise programs (even home-based or low-intensity exercise) can help preserve muscle mass and is increasingly recommended in cirrhosis management[34].

Both sarcopenia and frailty have emerged as independent predictors of adverse outcomes in cirrhosis, providing prognostic information in addition to the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)/MELD-Na score. MELD captures liver dysfunction, but it fails to reflect the functional reserve and nutritional status that sarcopenia/frailty represent[35]. Numerous studies have shown that muscle loss and physical frailty confer a higher risk of mortality, transplant waitlist dropout, and other complications even after adjusting for MELD severity[36]. One meta-analysis of 22 studies found that sarcopenia roughly doubled the risk of mortality in cirrhosis [pooled hazard ratio (HR): 2.13][37]. Importantly, this effect spans both pretransplant and post-transplant periods. Sarcopenia predicts a higher 3-month waitlist mortality (HR: 1.7) and higher post-transplant mortality (HR: 1.8) in pooled analyses[38]. In a large North American cohort, sex-specific muscle mass cutoffs [L3 skeletal muscle index (SMI) < 50 cm2/m2 in males or < 39 cm2/m2 in females] identified patients with sarcopenia at significantly increased risk of waitlist death[39].

Frailty as measured by objective tools like the Liver Frailty Index (LFI) or Short Physical Performance Battery similarly has strong prognostic power. In one multicenter study, each 1-point worsening in the LFI was associated with a 2-fold increase in waitlist mortality risk, independent of MELD-Na[40]. Adding an objective frailty score to MELD-Na significantly improved 3-month mortality prediction (in one model, the C-statistic improved from 0.80 to 0.82)[35]. In practical terms, a patient categorized as frail has a substantially higher likelihood of death or delisting on the transplant waitlist compared with a patient who is not frail with the same MELD score. Patients with an LFI ≥ 4.4 (severely frail) have been shown to experience an 80% higher waitlist mortality than patients with a much lower LFI even after acc

Muscle wasting contributes to complications like refractory ascites and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). Muscle is a key site for ammonia metabolism. Therefore, patients with sarcopenia are less able to buffer ammonia surges. Indeed, sarcopenia is a strong risk factor for overt HE. One prospective study showed that all patients who developed post-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) encephalopathy were sarcopenic, and sarcopenia increased HE risk > 30-fold in multivariate analysis[42]. Longitudinal data also suggest that progressive muscle loss correlates with higher rates of new decompensation (e.g., ascites, infections)[43].

Patients who are frail experience more frequent and longer hospitalizations. In a 12-month analysis of transplant candidates, 58% of patients who were frail (vs 36% of non-frail) required at least one hospital admission, and frailty was independently associated with a greater number of hospital days even after adjusting for MELD and other factors. Infections are also more common. Sarcopenia and malnutrition impair immune competence, contributing to higher inci

Both conditions are linked to worse health-related quality of life, functional dependency, and depression[45].

Frailty often leads to waitlist dropout, meaning patients either die or become too sick for transplantation before an organ is available. This occurs even in patients with relatively low MELD scores, underscoring that frailty captures risk not reflected by liver chemistry alone. Notably, the impact of frailty on waitlist outcomes is most pronounced when wait times are long. A Spanish multicenter study found that candidates who were frail had far higher mortality if waitlisted > 6 months, suggesting frailty becomes a critical determinant when transplantation is not immediate[46].

Pretransplant sarcopenia and frailty also adversely affect transplant recovery and long-term success. Patients with frailty or sarcopenia have longer intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stays after liver transplant, higher 30-day complication rates, and an increased likelihood of non-home discharge for rehabilitation. One analysis of 1166 patients in the United States found that those classified as frail prior to transplant had a 62% higher risk of post-transplant mortality at 1 year (unadjusted)[47]. They also had significantly higher odds of prolonged postoperative hospitalization [odds ratio (OR): 2.0], prolonged ICU requirement (OR: 1.6), early rehospitalization within 90 days (OR: 1.7), and discharge to a nursing facility rather than home (OR: 2.5)[47]. Frailty begets poorer transplant outcomes. Patients who enter surgery with a low physiological reserve recover more slowly and are more prone to infections, graft failure, and other complications. Importantly, most patients do see improvements in frailty after a successful transplant, but a subset (especially those who were severely frail before liver transplantation) continue to have functional deficits 1 year later[43,48].

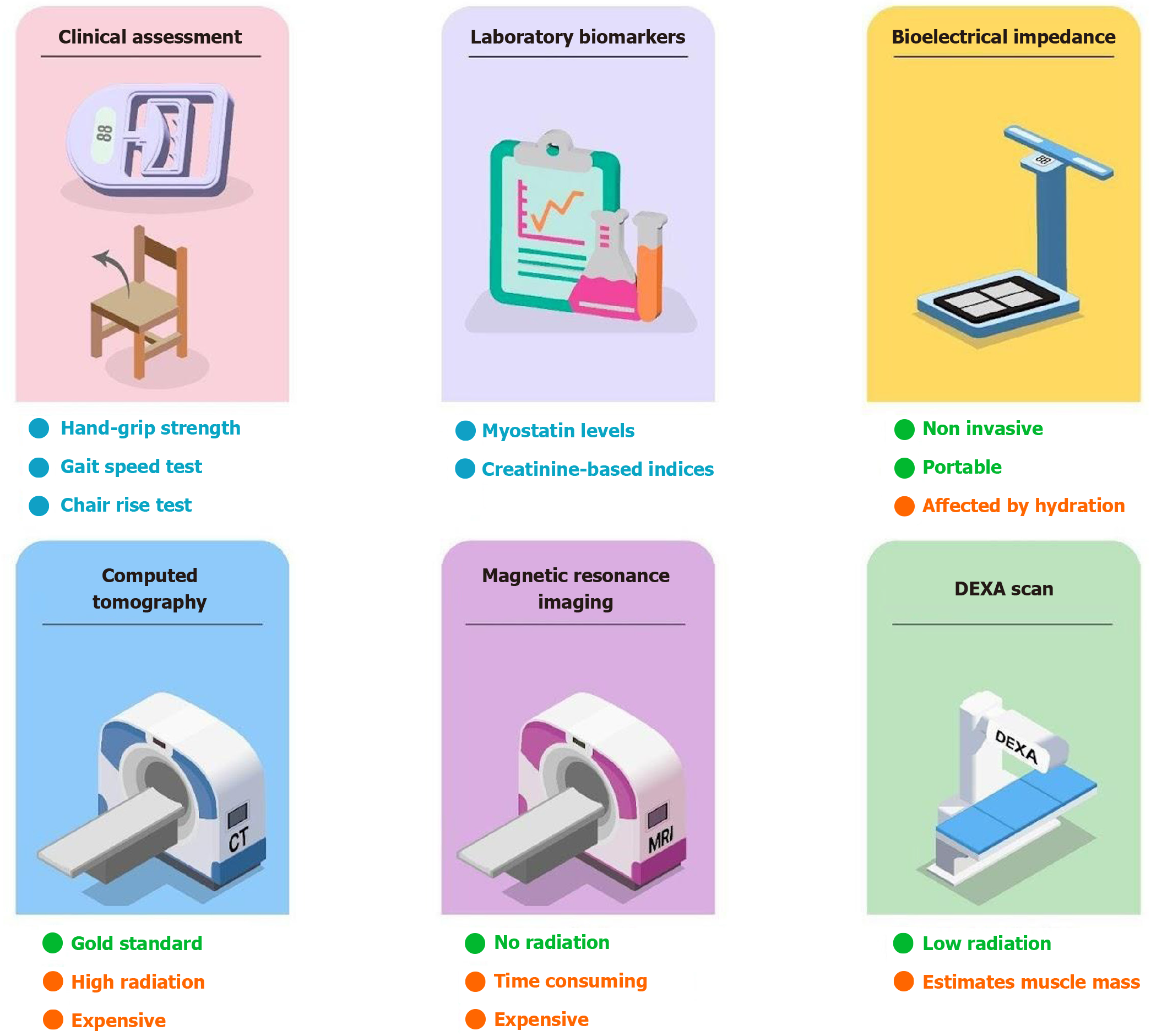

The diagnosis of sarcopenia is based on confirmation of low muscle mass and low muscle strength or low physical performance (Figure 5). Computed tomography (CT) is currently the gold standard tool used for the diagnosis of sarcopenia[49-54]. The metrics used by CT to make the diagnosis are skeletal muscle area (in cm2), SMI (in cm2/m2), psoas muscle index, and muscle radiation attenuation[55,56]. However, the complexity of the procedure and high costs make CT a more preferred tool for diagnosis. Inconsistent cutoff points and high radiation are the drawbacks of using CT for the diagnosis[57].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another imaging tool that can be used for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. MRI uses quantification of skeletal muscle fat content and area to make the diagnosis[49,50]. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is an alternative method used to diagnose sarcopenia. It exposes the patient to significantly lower levels of ra

Clinical indicators of sarcopenia include diminished handgrip strength, chair rise test, gait speed test, timed-up-and-go test, and short physical performance battery. These markers can be used for bedside assessment of sarcopenia[62,63]. A concise summary of the commonly used diagnostic investigations and defined cutoffs is summarized in Table 2.

| Investigation | Defined cutoff | Correlation with pretransplant mortality |

| Short physical performance battery | Frail = score less than or equal to 9/12 | Yes (> 65 years age) |

| Liver Frailty Index score | Frail = 4.5 | Yes |

| 6-minute walk test | < 250 m | Yes, mortality reduces by 52% |

| Bioelectrical impedance analysis | ASMI; Males: < 7.0 kg/m2; Females: < 5.7 kg/m2 | Yes |

| Hand grip test | Males: 26 kg; Females: 18 kg | Yes |

| Skeletal muscle index | Males: < 50 cm2/m2; Females: < 39.50 cm2/m2 | Yes |

| Appendicular lean mass-height adjusted | Males: < 6.57 kg/50 m2; Females: < 4.61 kg/m2 | Yes |

| DEXA upper limb lean mass-height-adjusted | Males: < 1.6 kg/m2 | Yes (males) |

| MRI: Fat-free muscle area at the level of the superior mesenteric artery | Males: FFMA < 3197.50 mm2; Females: FFMA < 2895.50 mm2 |

The diagnosis of frailty can be made using a variety of assessment tools. A standard for the assessment of frailty is the Groningen Frailty Indicator. It is a screening instrument containing 15 items. It determines loss of function by assessing four domains including physical, cognitive, social, and psychological. The Fried Physical Frailty Phenotype is another tool that is used as an indicator to quantify frailty. It uses five criteria for identification (unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, weakness, slow walking speed, and low physical activity)[64,65].

The Clinical Frailty Scale is a tool to diagnose frailty that considers pre-existing levels of function and mobility and classifies patients from very fit to terminally ill based on pictograms and descriptors[65]. The LFI is an assessment tool for frailty that is the most preferred tool for diagnosis of frailty in patients with liver disease. It has advantages over other tools as it was developed specifically for patients with the diagnosis of cirrhosis. It is also a more objective scale compared with other tools[66]. The Short Physical Performance Battery, chair stand test, and gait speed test are also indicators of frailty along with sarcopenia[66-68].

Integrating sarcopenia and frailty screening into routine hepatology care is essential given their prognostic importance.

All patients with cirrhosis, especially those with advanced disease or awaiting transplant, should undergo baseline frailty assessment and periodic reassessment during follow-up. A reasonable clinic workflow is to perform a quick screening test at the initial visit (such as grip strength, gait speed, or a LFI calculation), taking only a few minutes but yielding valuable information. Patients with normal results (robust) can be rescreened at least annually, whereas those with borderline or positive screens should receive further evaluation and intervention immediately. Importantly, this process can be streamlined using simple tools and existing clinic resources. For example medical assistants can measure handgrip strength while taking vital signs or utilize the South Asian Research Consortium-F questionnaire during their visit. Many components of frailty assessment (walking speed, chair stand test) require minimal equipment (stopwatch, chair, 4-m hallway) and can be incorporated into routine visits without specialist referral.

If performance-based tests are not feasible (e.g., the patient is acutely ill or unable to cooperate), then assessing muscle mass via recent imaging or anthropometry is the next option. Clinics can leverage existing CT or MRI scans for any patients with cirrhosis who undergo abdominal imaging (for hepatocellular carcinoma screening, etc.). Providers should consider having the radiology team quantify the L3 SMI, which can identify sarcopenia without extra cost or radiation. Some centers have protocolized this by adding a comment in cross-sectional imaging reports regarding muscle wasting if present[38,69,70].

In order to improve the prognosis in patients with cirrhosis and sarcopenia, a stringent check on complications such as ascites, HE, and portal hypertension needs to be maintained[71,72]. Ascites limits muscle functionality and can contribute to muscle loss via reduced appetite and dietary protein intake due to the compressive effect of intra-abdominal fluid[71]. Management is focused on sodium restriction and diuresis of extra fluid with cautious use of loop diuretics as they are known to cause sarcopenia at higher doses due to inhibition of NKCC1, a cotransporter protein also highly expressed in skeletal muscle and essential for myogenesis and hypertrophy[71,73-75]. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone and tolvaptan have demonstrated the potential to reduce sarcopenia as mineralocorticoid receptors have a central role in insulin resistance and critical catabolic pathways like aging of skeletal muscle by promoting inflammation and oxidative stress in muscles[71,76-78].

Hyperammonemia is known to cause HE and sarcopenia via mTOR inhibition reducing the protein synthesis and increasing proteolysis, autophagy, and oxidative stress in skeletal muscle[79,80]. Rifaximin and lactulose are key drugs that lower ammonia to help patients with HE and improve cognitive function as well as sarcopenic decline[71,81]. Rifaximin is an antibiotic that reduces ammonia via the urease enzyme producing gut bacteria. Lactulose increases the gut clearance of ammonia via acidification into ammonium ions. Fecal microbiota transplantation has shown promising results in the restoration of healthy gut microbiome and treatment of HE. However, it is still under study for efficacy and safety[71,82].

TIPS, initially devised for acute refractory variceal bleeding in patients with advanced portal hypertension, has also been proven to be helpful for other complications such as refractory ascites and hepatic hydrothorax[83]. The TIPS procedure has demonstrable benefits in cirrhosis symptoms and is indirectly helpful for muscle health with a reduction in protein-wasting ascites and an increase in intestinal protein uptake by improving gastrointestinal edema[71,83-85]. However, TIPS can result in HE and early liver failure due to diversion of the already compromised portal blood flow bypassing hepatic detoxification and leading to liver hypoperfusion. Therefore, the shunt placement should be used with caution in patients with severe liver disease, history and risk of HE, and poor cardiac reserve. It should be considered only as a last resort or a bridge to transplant[83].

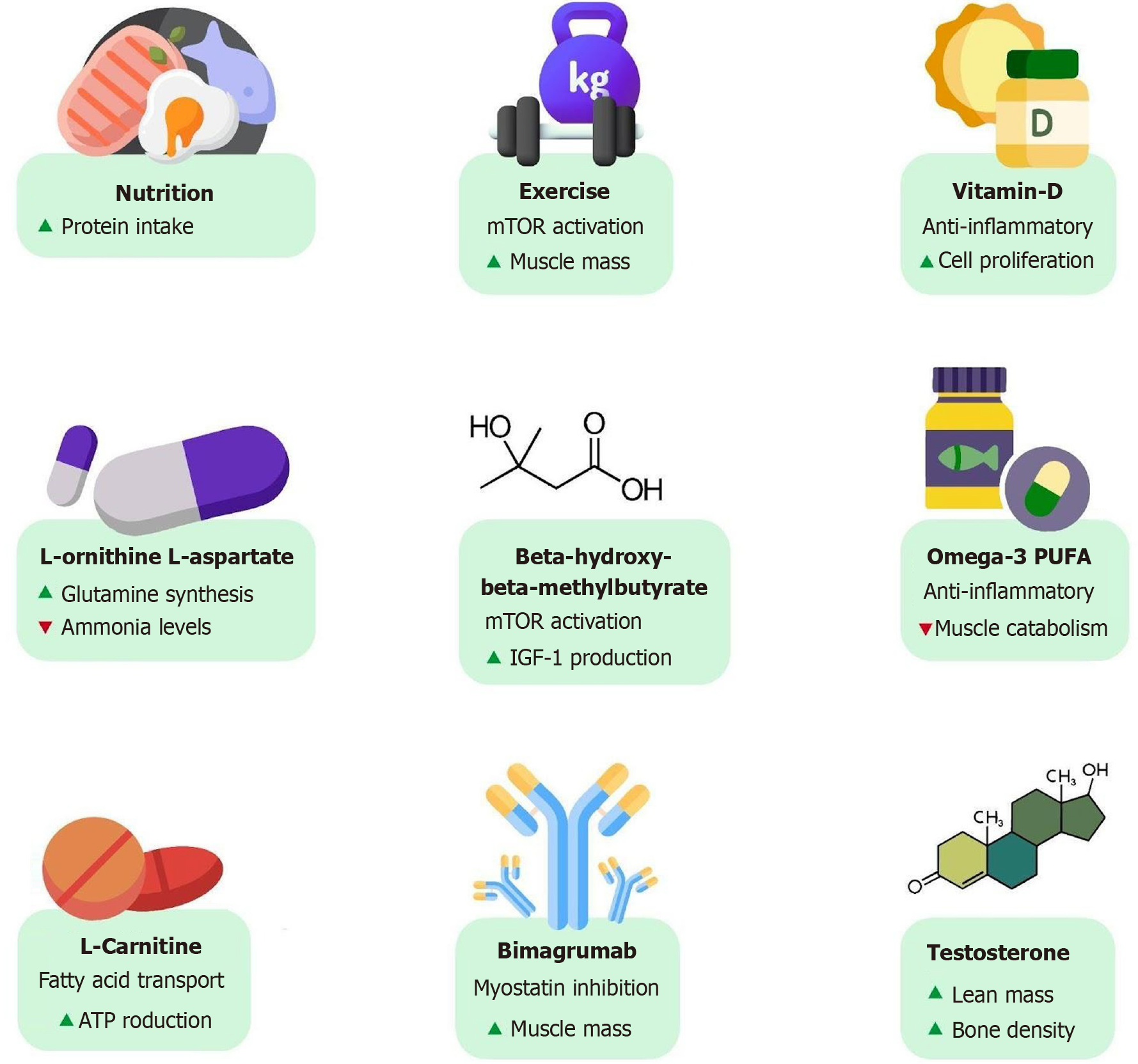

Nutritional status and muscle mass of a patient are key determinants of clinical outcomes in cirrhosis. Early diagnosis and intervention for malnutrition and sarcopenia are crucial to improve patient prognosis and quality of life. They should receive proper dietary counseling and educational resources[81,86]. The nutritional interventions are aimed at countering the increased metabolic demands in cirrhosis and breakdown of muscle mass[71,81,86].

A protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg per day is the goal for patients with cirrhosis, and up to 2.0 g/kg per day is recom

In cirrhosis there is decreased hepatic clearance of aromatic and sulfur-containing amino acids in conjunction with an increased breakdown of BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, valine) in skeletal muscle. The absence of isoleucine in hemoglobin makes blood a low biological value protein source that explains the post-bleeding catabolism state. Isoleucine infusion in upper gastrointestinal bleeding-simulated studies has been found to stimulate hepatic and muscle protein synthesis[87,95,96].

BCAA supplementation at a dose of 0.25 g/kg per day is recommended if the patient is unable to meet daily protein requirements via diet. Multiple trials have suggested that long-term supplementation of BCAAs can prevent progressive liver failure, improve muscle mass, quality of life, and survival rates in patients with sarcopenia, and lower HE events with an overall better neuropsychiatric status[97-102].

Patients with cirrhosis have been found to possess lower physical fitness levels and physiologic reserve than patients with other chronic diseases. This can be attributed to malnutrition, muscle loss, ascites and pedal edema, frequent hospitalizations, and HE[103,104]. Exercise strategies are targeted to increase muscle mass and function thus improving the baseline physical fitness for activities of daily living. The evidence on optimal exercise strategies is still evolving, but numerous studies focusing on both aerobic and resistance training across a spectrum of patients on the transplant waitlist to post-transplant periods have shown promising results in improving cardiopulmonary fitness and enhancing or at least preserving the skeletal muscle mass and strength[105-108]. Resistance exercises are known to increase muscle protein synthesis by activating mTOR signaling pathways, which are involved in muscle growth and repair[72].

Structured training programs for a minimum duration of 8-12 weeks aimed at 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise and at least 2 days of resistance exercise per week have shown to improve clinically valuable endpoints such as SMI, handgrip strength, peak torque in isokinetic knee extension, cross-sectional area of quadriceps muscle, peak exercise capacity, 6-minute walk test, hepatic venous pressure gradient, and quality of life through validated questionnaires[88,106,109-115]. Although exercise programs have resulted in reduced portal pressure with time, in the initial periods variceal prophylaxis with beta-blockers is recommended to counter the exercise-related rise in portal pressure[113,115,116].

Studies have been conducted for both site-based and home-based training programs with demonstrable benefits on both muscle mass and aerobic capacity. Although facility-based training programs might offer better supervision and reach higher intensities with the specialized equipment, financial and personnel resources and follow-up in the long term can be an issue of concern. Still, the adherence to exercise interventions has been found to be better in the site-based pro

In the STRIVE trial that focused on a home-based program, adherence was extremely poor (14%) even after the in

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Serper et al[118] tested prehabilitation intervention to maximize early recovery (known as PRIMER) in liver transplantation with a 14-week home-based behavioral program to promote physical activity. It included financial incentives and text-based nudges linked to wearable fitness trackers. The trial was found to be feasible and highly acceptable and led to increased daily steps (P = 0.02) in the intervention group compared with the control group among liver transplant candidates[118]. A number of similar and wider scale studies are underway to check the efficacy of prehabilitation programs. Table 3 summarizes the nutritional and exercise-based reco

| Therapeutic recommendation | Details |

| Nutrition | N/A |

| Protein intake[51,60,65,66] | 1.2-1.5 g/kg body weight per day; Up to 2.0 g/kg body weight per day for critically ill |

| Timing and pattern[51,71,73] | Small meals every 3-4 waking hours; Early breakfast; Late evening or nighttime snack |

| Branched-chain amino acid supplementation[27-32] | If unable to meet daily protein requirements |

| Not critically ill | 0.25 g/kg body weight per day; Critically ill: Insufficient evidence to supplement in this population |

| Exercise | Safety screening and assessment; Variceal prophylaxis as required; Supervised training programs; Start low, go slow; Moderate intensity; Motivational interviewing, maximizing engagement and adherence[51,60,91]; Aerobic exercise such as walking 4-7 days a week for a total of 150 minutes; Resistance exercises such as weight or band training for 2-3 days per week; Flexibility and balance exercises, including stretching for 2-3 days per week |

Levels of testosterone, an important anabolic hormone, are generally reduced in males with cirrhosis, strongly correlating with the severity of liver disease[119,120]. Low testosterone levels have been found to be associated with increased mortality, independent of the MELD score[119,121]. This is unsurprising as low testosterone is directly related to a loss of muscle mass that can lead to frailty. In an RCT conducted by Sinclair et al[119] over 12 months, testosterone therapy significantly increased the total lean mass, bone mineral density, and total bone mass in patients with cirrhosis with low serum testosterone compared with the placebo. However, it was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in mortality (16% vs 25.5%, P = 0.352)[112,119]. The routine use of testosterone is limited due to the potential concern for increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and cardiovascular events[71,112,122,123].

BCAAs and L-ornithine L-aspartate have been found to enhance the resolution of HE. This is attributed to promotion of ammonia metabolism by increasing glutamine synthesis in skeletal muscle[99,124]. Rats which were given L-ornithine L-aspartate with rifaximin over 4 weeks in an experimental study also demonstrated a significant increase in muscle fiber size[71,125,126].

Leucine increases the synthesis of albumin via activation of mTOR to help with better plasma oncotic pressures and improvement of peripheral edema in these patients[99,127-130]. Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, an active metabolite of leucine, also activates the mTOR pathway and promotes IGF-1 production leading to anabolic effects on protein metabolism[131,132]. A pilot RCT conducted over 12 weeks in 24 patients with cirrhosis showed significantly improved muscle function with beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation. It was measured by the chair stand test (reduced from 14.2 ± 5.0 seconds to 11.7 ± 2.6 seconds, P < 0.05), 6-minute walk test (increased from 361.8 ± 68.0 m to 409.4 ± 58.0 m, P < 0.05), and quadriceps muscle mass (increased from 4.9 ± 1.8 mm to 5.4 ± 1.8 mm, P < 0.05)[132,133].

Long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and medium chain fatty acids have also shown beneficial results in malnutrition and sarcopenia with their anti-inflammatory properties reducing the impact of inflammation on anabolic signals in skeletal muscle[132,134-136]. The vitamin D receptor is a nuclear transcription factor strongly expressed in skeletal muscle that enhances cell proliferation and differentiation and has anti-inflammatory properties[132,137,138]. Vitamin D supplementation in patients with cirrhosis showed a significant improvement in SMI (P = 0.002) after 12 months[132,139-142]. A number of studies have shown beneficial results with L-carnitine use in reducing ammonia levels and increasing muscle mass and function. Notably, it transports long chain fatty acids into mitochondria for ATP pro

Myostatin, which is a negative regulator of muscle mass, inhibits protein synthesis and causes proteolysis. It is upregulated in cirrhosis and various other chronic diseases and plays a central role in muscle atrophy[132,145-147]. Follistatin is a glycoprotein and a natural antagonist to myostatin. Its administration in rat models showed promising results with respect to muscle mass and strength but with mixed results in human studies. It is still being evaluated[132,148,149]. Monoclonal antibodies targeting myostatin like landogrozumab and bimagrumab are currently being studied with great interest. A phase II RCT showed improvement in lean muscle mass with bimagrumab added to lifestyle modifications and oral supplements in patients with sarcopenia[132,150]. Table 4 provides an overview of emerging therapies for sarcopenia along with their proposed mechanisms of action (Figure 6).

| Emerging therapies | Proposed mechanism |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone and tolvaptan | Mineralocorticoid receptors have a central role in insulin resistance and critical catabolic pathways like aging of skeletal muscle |

| L-ornithine L-aspartate | Promotes ammonia metabolism by increasing glutamine synthesis in skeletal muscle |

| Leucine | Increases the synthesis of albumin |

| Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate | Activates the mTOR pathway and promotes IGF-1 production = anabolic effects |

| Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and medium-chain fatty acids | Anti-inflammatory properties |

| Vitamin D | Enhances cell proliferation and differentiation |

| L-carnitine | Enhances ATP production for muscle function |

| Follistatin | Natural antagonist to myostatin |

| Landogrozumab and bimagrumab | Monoclonal antibodies targeting myostatin |

The relationship between hepatic decompensation and muscle loss in cirrhosis is cyclic. Cirrhosis is a major cause of the development of malnutrition, sarcopenia, and frailty. These conditions in turn perpetuate the risk of liver dec

A study including 669 patients with cirrhosis found that patients with sarcopenia had a shorter median survival than patients without sarcopenia (20 ± 3 months vs 95 ± 24 months, P < 0.001). Additionally, the authors suggested that a modified MELD score taking sarcopenia into account is a better prognostic index for mortality in patients with cirrhosis, primarily those with low MELD scores[4]. Following TIPS placement there is a significantly higher rate of acute-on-chronic liver failure development in patients with sarcopenia compared to patients without sarcopenia[112,151,152]. Ascites and HE are known predictors of mortality in cirrhosis. Patients without sarcopenia were found to have faster resolution of ascites after TIPS[152]. In a study of 675 patients with cirrhosis, sarcopenia was found to be associated with an increased risk of HE (OR: 2.42, P = 0.001) and mortality (cause-specific HR: 2.15, P < 0.001), independent of the MELD score[153].

The prognosis and determination of liver transplant candidates among patients with cirrhosis has been determined by liver and kidney function markers that give a MELD score or overt clinical presentations like ascites and HE[154,155]. However, insidious complications such as malnutrition, muscle wasting, and physical frailty are also key predictors of morbidity, mortality, and transplant outcomes. Thus, it should be considered in the transplant evaluation[71,156,157]. The severity of sarcopenia and frailty in liver transplant candidates correlates with a reduced quality of life[158], longer hospital and ICU stays[159,160], increased mortality while on the waitlist, and a higher likelihood of transplant delisting[112,157,161-163]. Even after transplantation, sarcopenia may persist for up to 1 year and cause reduced survival. This can in part be attributed to post-transplant immunosuppressants like corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors[157,164].

A study showed that the addition of the novel LFI to the MELD score resulted in better prediction of waitlist mortality[154,165]. Another study that utilized the psoas muscle index as a measurement for sarcopenia demonstrated significantly lower 1-year and 5-year survival rates in patients with sarcopenia awaiting liver transplantation compared to candidates without sarcopenia [59% vs 94% and 54% vs 80%, respectively (P < 0.001)][157,166]. It was proposed that patients with sarcopenia or frailty should be given priority for liver transplantation given the high morbidity and mortality on the waitlist. However, based on the severity of patient conditions, transplant delisting may be justified if associated with poor post-transplant prognosis[167].

Results of a prospective study showed that patients with decompensated cirrhosis and sarcopenia had a longer ICU stay (4.1 ± 2.2 days vs 3.1 ± 1.1 days, P = 0.008), higher rate of major complications (45.2% vs 22.1%, P = 0.001), higher post-liver transplant mortality (15.1% vs 2.9%, P = 0.003) and a shorter 1-year overall survival post-liver transplant (P < 0.001) than in those without sarcopenia[168]. Table 5 summarizes key clinical outcomes associated with sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis, highlighting its impact on survival, complications, and post-transplant prognosis.

| Ref. | Objectives | Methodology | Findings |

| Montano-Loza et al[160] | To evaluate the impact of sarcopenia in cirrhosis | 669 cirrhotic patients using a novel MELD-sarcopenia score derived through Cox proportional hazards regression | Patients with sarcopenia had shorter median survival than non-sarcopenic patients (20 ± 3 months vs 95 ± 24 months, P < 0.001); MELD-sarcopenia score was associated with improved prediction of mortality |

| Bhanji et al[153] | To evaluate if sarcopenia is associated with overt hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotics and evaluate its impact on mortality | 675 cirrhotics with CT to evaluate sarcopenia | Sarcopenia was associated with an increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy (OR 2.42; 95%CI: 1.43-4.10, P = 0.001) and mortality (csHR 2.15, P < 0.001), independent of the MELD score |

| Zhou et al[168] | To investigate the association between sarcopenia and 1-year overall survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis after liver transplantation | 222 cirrhotics who underwent LT were followed up to compare and evaluate postoperative outcomes | Decompensated cirrhotics with sarcopenia had a longer ICU stay (4.1 ± 2.2 days vs 3.1 ± 1.1 days, P = 0.008), higher rate of major complications (45.2% vs 22.1%, P = 0.001), higher post-LT mortality (15.1% vs 2.9%, P = 0.003) with a shorter 1-year overall survival post-LT (P < 0.001), than in those without sarcopenia |

| Golse et al[166] | To evaluate the impact of sarcopenia on post-LT survival | 256 patients with cirrhosis who underwent liver transplantation were selected retrospectively to study for post-LT survival | Significantly lower 1- and 5-year survival rates post-LT were reported in patients with sarcopenia (59% vs 94% and 54% vs 80%, respectively P < 0.001), compared to candidates without sarcopenia. (utilized the psoas muscle area as a measurement for sarcopenia, PMA was found to offer better accuracy than L3SMI) |

| Lai et al[154] | To develop a novel frailty index, encompassing extrahepatic complications of cirrhosis- muscle wasting, malnutrition and functional decline, as an improved mortality predictor in ESLD | 536 cirrhotics (MELD-Na > 18) listed for LT. Final Frailty Index comprised of- grip strength, chair stands, and balance which were identified by best subset selection analyses with Cox regression to predict the waitlist mortality | Addition of Novel LFI to MELD score resulted in better prediction of waitlist mortality and has potential clinical utility to predict outcomes over a longer term on waitlist. Compared with MELD-Na alone, MELD-Na + Frailty Index correctly re-classified 16% of deaths/delistings (P = 0.005) and 3% of non-deaths/delistings (P = 0.17) with a total mortality of 19% (P < 0.001) |

Severe malnutrition has also been found to be independently associated with post-liver transplant infections, sepsis, greater ventilator dependency (> 24 hours) and ICU stay, and notably, an increased need for blood transfusion intra- and peri-operative[169,170]. Dhaliwal et al[171] retrospectively studied sarcopenia-related outcomes in patients undergoing liver re-transplantation. Interestingly, of the 57 patients who underwent liver re-transplantation, 47% had sarcopenia. Patients with sarcopenia had a shorter median time between the first and second transplant (16.7 months vs 36.5 months, P = 0.34), compared to the group without sarcopenia. A meta-analysis of twenty-five studies that involved 7760 patients found an increased risk of post-liver transplant mortality (adjusted HR: 1.58; 95%CI: 1.21–2.07) and a longer ICU stay, a high risk ratio of sepsis, and serious post-liver transplant complications in patients with preoperative sarcopenia than those without sarcopenia[172].

It is important to understand that sarcopenia and frailty are not peripheral. They are central to the cirrhosis phenotype. Early identification and multimodal intervention is crucial for the management of these patients in order to mitigate the associated morbidity and mortality while awaiting liver transplantation. Sarcopenia/frailty-based prognostic models need to be integrated into liver transplant evaluation. Structured prehabilitation programs with multidisciplinary invo

| 1. | Lai JC, Tandon P, Bernal W, Tapper EB, Ekong U, Dasarathy S, Carey EJ. Malnutrition, Frailty, and Sarcopenia in Patients With Cirrhosis: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;74:1611-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lowe R, Hey P, Sinclair M. The sex-specific prognostic utility of sarcopenia in cirrhosis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:2608-2615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Atay K, Aydin S, Canbakan B. Sarcopenia and Frailty in Cirrhotic Patients: Evaluation of Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Single-Centre Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montano-Loza AJ, Duarte-Rojo A, Meza-Junco J, Baracos VE, Sawyer MB, Pang JX, Beaumont C, Esfandiari N, Myers RP. Inclusion of Sarcopenia Within MELD (MELD-Sarcopenia) and the Prediction of Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tandon P, Tangri N, Thomas L, Zenith L, Shaikh T, Carbonneau M, Ma M, Bailey RJ, Jayakumar S, Burak KW, Abraldes JG, Brisebois A, Ferguson T, Majumdar SR. A Rapid Bedside Screen to Predict Unplanned Hospitalization and Death in Outpatients With Cirrhosis: A Prospective Evaluation of the Clinical Frailty Scale. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1759-1767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cron DC, Friedman JF, Winder GS, Thelen AE, Derck JE, Fakhoury JW, Gerebics AD, Englesbe MJ, Sonnenday CJ. Depression and Frailty in Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease Referred for Transplant Evaluation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1805-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dajti E, Rodrigues SG, Perazza F, Colecchia L, Marasco G, Renzulli M, Barbara G, Azzaroli F, Berzigotti A, Colecchia A, Ravaioli F. Sarcopenia evaluated by EASL/AASLD computed tomography-based criteria predicts mortality in patients with cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JHEP Rep. 2024;6:101113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alhaddad O, Elsabaawy M, Abedelhai A, Badra G, Elfayoumy M. Impact of age on frailty in liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25:203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48:16-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6646] [Cited by in RCA: 8966] [Article Influence: 1280.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Tantai X, Liu Y, Yeo YH, Praktiknjo M, Mauro E, Hamaguchi Y, Engelmann C, Zhang P, Jeong JY, van Vugt JLA, Xiao H, Deng H, Gao X, Ye Q, Zhang J, Yang L, Cai Y, Liu Y, Liu N, Li Z, Han T, Kaido T, Sohn JH, Strassburg C, Berg T, Trebicka J, Hsu YC, IJzermans JNM, Wang J, Su GL, Ji F, Nguyen MH. Effect of sarcopenia on survival in patients with cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2022;76:588-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 70.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1232-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Shalimar, Rout G, Kumar R, Singh AD, Sharma S, Gunjan D, Saraya A, Nayak B, Acharya SK. Persistent or incident hyperammonemia is associated with poor outcomes in acute decompensation and acute-on-chronic liver failure. JGH Open. 2020;4:843-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Han DW. Intestinal endotoxemia as a pathogenetic mechanism in liver failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:961-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dasarathy S, Hatzoglou M. Hyperammonemia and proteostasis in cirrhosis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Olde Damink SW, Deutz NE, Dejong CH, Soeters PB, Jalan R. Interorgan ammonia metabolism in liver failure. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Holeček M. The role of skeletal muscle in the pathogenesis of altered concentrations of branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) in liver cirrhosis, diabetes, and other diseases. Physiol Res. 2021;70:293-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang X, Yang G, Jiang S, Ji B, Xie W, Li H, Sun J, Li Y. Causal Relationship Between Gut Microbiota, Metabolites, and Sarcopenia: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024;79:glae173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qiu Y, Yu J, Li Y, Yang F, Yu H, Xue M, Zhang F, Jiang X, Ji X, Bao Z. Depletion of gut microbiota induces skeletal muscle atrophy by FXR-FGF15/19 signalling. Ann Med. 2021;53:508-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tilg H, Wilmer A, Vogel W, Herold M, Nölchen B, Judmaier G, Huber C. Serum levels of cytokines in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:264-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin SY, Chen WY, Lee FY, Huang CJ, Sheu WH. Activation of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is involved in skeletal muscle wasting in a rat model with biliary cirrhosis: potential role of TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E493-E501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moctezuma-Velázquez C, Low G, Mourtzakis M, Ma M, Burak KW, Tandon P, Montano-Loza AJ. Association between Low Testosterone Levels and Sarcopenia in Cirrhosis: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17:615-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Møller S, Becker U. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and growth hormone in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis. 1992;10:239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu W, Thomas SG, Asa SL, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Bhasin S, Ezzat S. Myostatin is a skeletal muscle target of growth hormone anabolic action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5490-5496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Krähenbühl L, Lang C, Lüdes S, Seiler C, Schäfer M, Zimmermann A, Krähenbühl S. Reduced hepatic glycogen stores in patients with liver cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2003;23:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nakaya Y, Harada N, Kakui S, Okada K, Takahashi A, Inoi J, Ito S. Severe catabolic state after prolonged fasting in cirrhotic patients: effect of oral branched-chain amino-acid-enriched nutrient mixture. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:531-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Owen OE, Trapp VE, Reichard GA Jr, Mozzoli MA, Moctezuma J, Paul P, Skutches CL, Boden G. Nature and quantity of fuels consumed in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1821-1832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chiang JYL, Ferrell JM. Discovery of farnesoid X receptor and its role in bile acid metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2022;548:111618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Herrmann M, Rodriguez-Blanco G, Balasso M, Sobolewska K, Semeraro MD, Alonso N, Herrmann W. The role of bile acid metabolism in bone and muscle: from analytics to mechanisms. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2024;61:510-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Luthra M, Mehta V, Bedi G, Gupta Y, Goyal M. Study of Risk Factors in Patient with Advanced Fibrosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Mild Elevation of Transaminases. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;13:S123-S124. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Thapaliya S, Runkana A, McMullen MR, Nagy LE, McDonald C, Naga Prasad SV, Dasarathy S. Alcohol-induced autophagy contributes to loss in skeletal muscle mass. Autophagy. 2014;10:677-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Egerman MA, Glass DJ. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sanchez AM, Csibi A, Raibon A, Cornille K, Gay S, Bernardi H, Candau R. AMPK promotes skeletal muscle autophagy through activation of forkhead FoxO3a and interaction with Ulk1. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:695-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Goyal MK, Goyal P, Goyal O, Sood A. Gut feeling gone wrong: Tangled relationship between disorders of gut-brain interaction and liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2025;17:105582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 34. | Sirisunhirun P, Bandidniyamanon W, Jrerattakon Y, Muangsomboon K, Pramyothin P, Nimanong S, Tanwandee T, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Chainuvati S, Chotiyaputta W. Effect of a 12-week home-based exercise training program on aerobic capacity, muscle mass, liver and spleen stiffness, and quality of life in cirrhotic patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lai JC, Yang B, Lee HW, Lin H, Tsochatzis EA, Petta S, Bugianesi E, Yoneda M, Zheng MH, Hagström H, Boursier J, Calleja JL, Goh GB, Chan WK, Gallego-Duràn R, Sanyal AJ, de Lédinghen V, Newsome PN, Fan JG, Castera L, Lai M, Fournier-Poizat C, Wong GL, Pennisi G, Armandi A, Nakajima A, Liu WY, Shang Y, Saint-Loup M, Llop E, Teh KKJ, Lara-Romero C, Asgharpour A, Mahgoub S, Chan MS, Canivet CM, Romero-Gómez M, Kim SU, Wong VW, Yip TC. Non-invasive risk-based surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Gut. 2025;74:2050-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Montano-Loza AJ, Meza-Junco J, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Baracos VE, Bain VG, Sawyer MB. Muscle wasting is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:166-173, 173.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Zeng X, Shi ZW, Yu JJ, Wang LF, Luo YY, Jin SM, Zhang LY, Tan W, Shi PM, Yu H, Zhang CQ, Xie WF. Sarcopenia as a prognostic predictor of liver cirrhosis: a multicentre study in China. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12:1948-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | van Vugt JL, Levolger S, de Bruin RW, van Rosmalen J, Metselaar HJ, IJzermans JN. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Computed Tomography-Assessed Skeletal Muscle Mass on Outcome in Patients Awaiting or Undergoing Liver Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2277-2292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Georgiou A, Papatheodoridis GV, Alexopoulou A, Deutsch M, Vlachogiannakos I, Ioannidou P, Papageorgiou MV, Papadopoulos N, Yannakoulia M, Kontogianni MD. Validation of cutoffs for skeletal muscle mass index based on computed tomography analysis against dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in patients with cirrhosis: the KIRRHOS study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2020;33:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Haugen CE, McAdams-DeMarco M, Holscher CM, Ying H, Gurakar AO, Garonzik-Wang J, Cameron AM, Segev DL, Lai JC. Multicenter Study of Age, Frailty, and Waitlist Mortality Among Liver Transplant Candidates. Ann Surg. 2020;271:1132-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lai JC, Sonnenday CJ, Tapper EB, Duarte-Rojo A, Dunn MA, Bernal W, Carey EJ, Dasarathy S, Kamath BM, Kappus MR, Montano-Loza AJ, Nagai S, Tandon P. Frailty in liver transplantation: An expert opinion statement from the American Society of Transplantation Liver and Intestinal Community of Practice. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1896-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nardelli S, Lattanzi B, Torrisi S, Greco F, Farcomeni A, Gioia S, Merli M, Riggio O. Sarcopenia Is Risk Factor for Development of Hepatic Encephalopathy After Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Placement. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:934-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Nardelli S, Riggio O, Gioia S, Merli M, Spagnoli A, di Martino M, Pelle G, Ridola L. Risk factors for hepatic encephalopathy and mortality in cirrhosis: The role of cognitive impairment, muscle alterations and shunts. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:1060-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sinclair M, Poltavskiy E, Dodge JL, Lai JC. Frailty is independently associated with increased hospitalisation days in patients on the liver transplant waitlist. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:899-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Giammarino AM, Ghani M, Satapathy SK. A brief review of sarcopenia and frailty in the early post-liver transplant period. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2024;23:e0215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Puchades L, Herreras J, Ibañez A, Reyes É, Crespo G, Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, Cortés L, Serrano T, Fernández-Yunquera A, Montalvá E, Berenguer M. Waiting time dictates impact of frailty: A Spanish multicenter prospective study. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Lai JC, Shui AM, Duarte-Rojo A, Ganger DR, Rahimi RS, Huang CY, Yao F, Kappus M, Boyarsky B, McAdams-Demarco M, Volk ML, Dunn MA, Ladner DP, Segev DL, Verna EC, Feng S; from the Multi‐Center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study. Frailty, mortality, and health care utilization after liver transplantation: From the Multicenter Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study. Hepatology. 2022;75:1471-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cui Y, Zhang M, Guo J, Jin J, Wang H, Wang X. Correlation between sarcopenia and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1342100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lee K, Shin Y, Huh J, Sung YS, Lee IS, Yoon KH, Kim KW. Recent Issues on Body Composition Imaging for Sarcopenia Evaluation. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20:205-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sergi G, Trevisan C, Veronese N, Lucato P, Manzato E. Imaging of sarcopenia. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1519-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Engelke K, Museyko O, Wang L, Laredo JD. Quantitative analysis of skeletal muscle by computed tomography imaging-State of the art. J Orthop Translat. 2018;15:91-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Sharma P, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Caracciolo JT, Fishman M, Poch MA, Pow-Sang J, Sexton WJ, Spiess PE. Sarcopenia as a predictor of overall survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:339.e17-339.e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, Baracos VE. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1822] [Cited by in RCA: 2497] [Article Influence: 138.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Baracos VE, Mazurak VC, Bhullar AS. Cancer cachexia is defined by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8:3-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | van der Werf A, Langius JAE, de van der Schueren MAE, Nurmohamed SA, van der Pant KAMI, Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Wierdsma NJ. Percentiles for skeletal muscle index, area and radiation attenuation based on computed tomography imaging in a healthy Caucasian population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:288-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hamaguchi Y, Kaido T, Okumura S, Kobayashi A, Hammad A, Tamai Y, Inagaki N, Uemoto S. Proposal for new diagnostic criteria for low skeletal muscle mass based on computed tomography imaging in Asian adults. Nutrition. 2016;32:1200-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Scott BR, Walker DM, Tesfaigzi Y, Schöllnberger H, Walker V. Mechanistic basis for nonlinear dose-response relationships for low-dose radiation-induced stochastic effects. Nonlinearity Biol Toxicol Med. 2003;1:93-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lustgarten MS, Fielding RA. Assessment of analytical methods used to measure changes in body composition in the elderly and recommendations for their use in phase II clinical trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:368-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Goyal MK, Mehta V, Prakash S, Grover K, Gupta Y, Singh A, Luthra M. Liver stiffness measurement as a surrogate marker of clinically significant portal hypertension. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;13:S36-S37. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 60. | Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gómez JM, Heitmann BL, Kent-Smith L, Melchior JC, Pirlich M, Scharfetter H, Schols AM, Pichard C; Composition of the ESPEN Working Group. Bioelectrical impedance analysis--part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1226-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1523] [Cited by in RCA: 1891] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 61. | Goyal MK, Dhaliwal KK, Agrawal S. "Syphilitic Hepatitis": A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Features, Diagnostic Approaches, and Management Considerations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58:635-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MITD, Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T, Baptista G, Barazzoni R, Blaauw R, Coats A, Crivelli A, Evans DC, Gramlich L, Fuchs-Tarlovsky V, Keller H, Llido L, Malone A, Mogensen KM, Morley JE, Muscaritoli M, Nyulasi I, Pirlich M, Pisprasert V, de van der Schueren MAE, Siltharm S, Singer P, Tappenden K, Velasco N, Waitzberg D, Yamwong P, Yu J, Van Gossum A, Compher C; GLIM Core Leadership Committee; GLIM Working Group. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 795] [Cited by in RCA: 1896] [Article Influence: 237.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, Brach J, Chandler J, Cawthon P, Connor EB, Nevitt M, Visser M, Kritchevsky S, Badinelli S, Harris T, Newman AB, Cauley J, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3358] [Cited by in RCA: 3220] [Article Influence: 214.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 64. | Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Frieswijk N, Slaets JP. Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:M962-M965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chong E, Ho E, Baldevarona-Llego J, Chan M, Wu L, Tay L, Ding YY, Lim WS. Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: Comparing Different Frailty Measures in Predicting Short- and Long-term Patient Outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:450-457.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ellis HL, Wan B, Yeung M, Rather A, Mannan I, Bond C, Harvey C, Raja N, Dutey-Magni P, Rockwood K, Davis D, Searle SD. Complementing chronic frailty assessment at hospital admission with an electronic frailty index (FI-Laboratory) comprising routine blood test results. CMAJ. 2020;192:E3-E8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Essam Behiry M, Mogawer S, Yamany A, Rakha M, Awad R, Emad N, Abdelfatah Y. Ability of the Short Physical Performance Battery Frailty Index to Predict Mortality and Hospital Readmission in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2019;2019:8092865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Dunn MA, Josbeno DA, Tevar AD, Rachakonda V, Ganesh SR, Schmotzer AR, Kallenborn EA, Behari J, Landsittel DP, DiMartini AF, Delitto A. Frailty as Tested by Gait Speed is an Independent Risk Factor for Cirrhosis Complications that Require Hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1768-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kusnik A, Penmetsa A, Chaudhary F, Renjith K, Ramaraju G, Laryea M, Allard JP. Clinical Overview of Sarcopenia, Frailty, and Malnutrition in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology Res. 2024;17:53-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Xu Z, Yang D, Luo J, Xu H, Jia J, Yang Z. Diagnosis of Sarcopenia Using the L3 Skeletal Muscle Index Estimated From the L1 Skeletal Muscle Index on MR Images in Patients With Cirrhosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2023;58:1569-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ghumman U, Lee B, Bigham D, Tsai E. Sarcopenia in cirrhosis: a clinical practice review. Ann Palliat Med. 2025;14:255-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Song Z, Moore DR, Hodson N, Ward C, Dent JR, O'Leary MF, Shaw AM, Hamilton DL, Sarkar S, Gangloff YG, Hornberger TA, Spriet LL, Heigenhauser GJ, Philp A. Resistance exercise initiates mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) translocation and protein complex co-localisation in human skeletal muscle. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Mandai S, Furukawa S, Kodaka M, Hata Y, Mori T, Nomura N, Ando F, Mori Y, Takahashi D, Yoshizaki Y, Kasagi Y, Arai Y, Sasaki E, Yoshida S, Furuichi Y, Fujii NL, Sohara E, Rai T, Uchida S. Loop diuretics affect skeletal myoblast differentiation and exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Hanai T, Shiraki M, Ohnishi S, Miyazaki T, Ideta T, Kochi T, Imai K, Suetsugu A, Takai K, Moriwaki H, Shimizu M. Rapid skeletal muscle wasting predicts worse survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:743-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Traub J, Reiss L, Aliwa B, Stadlbauer V. Malnutrition in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Nutrients. 2021;13:540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 76. | Namba M, Hiramatsu A, Aikata H, Kodama K, Uchikawa S, Ohya K, Morio K, Fujino H, Nakahara T, Murakami E, Yamauchi M, Kawaoka T, Tsuge M, Imamura M, Chayama K. Management of refractory ascites attenuates muscle mass reduction and improves survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:217-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Burton LA, McMurdo ME, Struthers AD. Mineralocorticoid antagonism: a novel way to treat sarcopenia and physical impairment in older people? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75:725-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Nucci RAB, Nóbrega ODT, Jacob-Filho W. Therapeutic Potential of Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Skeletal Muscle Aging. Receptors. 2025;4:13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 79. | Davuluri G, Allawy A, Thapaliya S, Rennison JH, Singh D, Kumar A, Sandlers Y, Van Wagoner DR, Flask CA, Hoppel C, Kasumov T, Dasarathy S. Hyperammonaemia-induced skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction results in cataplerosis and oxidative stress. J Physiol. 2016;594:7341-7360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Qiu J, Tsien C, Thapalaya S, Narayanan A, Weihl CC, Ching JK, Eghtesad B, Singh K, Fu X, Dubyak G, McDonald C, Almasan A, Hazen SL, Naga Prasad SV, Dasarathy S. Hyperammonemia-mediated autophagy in skeletal muscle contributes to sarcopenia of cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E983-E993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Tandon P, Zanetto A, Piano S, Heimbach JK, Dasarathy S. Liver transplantation in the patient with physical frailty. J Hepatol. 2023;78:1105-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Henin G, Lanthier N, Dahlqvist G. Pathophysiological changes of the liver-muscle axis in end-stage liver disease: what is the right target? Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2022;85:611-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Rajesh S, George T, Philips CA, Ahamed R, Kumbar S, Mohan N, Mohanan M, Augustine P. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhosis: An exhaustive critical update. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5561-5596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Liu J, Ma J, Yang C, Chen M, Shi Q, Zhou C, Huang S, Chen Y, Wang Y, Li T, Xiong B. Sarcopenia in Patients with Cirrhosis after Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Placement. Radiology. 2022;303:711-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hsu CS, Kao JH. Sarcopenia and chronic liver diseases. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:1229-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70:172-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 107.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 87. | Plauth M. Nutritional Intervention in Chronic Liver Failure. Visc Med. 2019;35:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Aby ES, Saab S. Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Malnutrition in Cirrhotic Patients. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:589-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Jonung T, Jeppsson B, Åslund U, Nair B. A comparison between meat and vegan protein diet in patients with mild chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Nutr. 1987;6:169-174. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Bianchi GP, Marchesini G, Fabbri A, Rondelli A, Bugianesi E, Zoli M, Pisi E. Vegetable versus animal protein diet in cirrhotic patients with chronic encephalopathy. A randomized cross-over comparison. J Intern Med. 1993;233:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |