Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.113485

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 153 Days and 23.5 Hours

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3, caused by mutations in the ABCB4 gene, is a rare genetic disorder. Although severe phenotypes due to bi

To describe the clinical spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation of ABCB4 mutations in children in a cohort of North Indian children.

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database from a single tertiary care centre. Children (≤ 18 years) with ABCB4 mutations between January 2021 and March 2025 were analysed. The clinical presentation, laboratory investigations, genetic sequencing and outcomes were recorded. Patients were stratified into group 1 (homozygous/compound heterozygous) and group 2 (he

Of the 26 patients, 16 had biallelic mutations, and 10 had monoallelic mutations. Group 1 exhibited higher rates of positive family history (75% vs 30%, P = 0.04), ascites (43.2% vs 0%, P = 0.02), larger varices (40% vs 0%, P = 0.009), higher gamma glutamyl transferase levels (171 U/L vs 38 U/L, P = 0.007), and lower platelet counts (162 × 109/L vs 415 × 109/L, P = 0.007). Notably, two-thirds of patients in group 1 experienced disease progression, and one-third died during follow-up. Certain missense variants (e.g., c.2860T>C) and all nonsense variants were linked to rapid deterioration. Most children in group 2 had transient cholestasis with a good outcome, but two older children succumbed.

Mutations in the ABCB4 gene contribute significantly to pediatric chronic liver disease. Patients with severe bi

Core Tip: Patients with ABCB4 mutations continue to pose an enigma for clinicians, and understanding of the varied manifestations continues to evolve. Children with biallelic mutations had a progressive disease with ascites, larger varices and decompensation. Children with monoallelic mutations fare better with significantly better liver function in follow-up; however, the risk of disease progression and decompensation remains and needs close monitoring. Protein-truncating mutations and missense mutations in highly conserved domains are associated with early disease progression. Early genetic testing and family screening may help in tailoring treatment and prognostication.

- Citation: Thunga C, Mitra S, Babbar A, Lal R, Pal A, Kakkar N, Lal SB. Clinical spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation of ABCB4 mutations in children: Insights from a North Indian cohort. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 113485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/113485.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.113485

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is a rare group of genetic cholestatic disorders, characterised by de

With the availability of NGS, diagnosis of PFIC is often done in patients with liver diseases, but this has revealed a spectrum of phenotypic heterogeneity, with presentations that can closely mimic other common causes of CLD. Notably, studies have reported classical features of PFIC3 even in individuals harbouring heterozygous (HET) ABCB4 mutations, often affecting multiple family members, thereby complicating diagnostic and management strategies[7]. Hence, in this study, we aim to describe the clinical spectrum and genotype–phenotype correlation of ABCB4 mutations in children in a large cohort of North Indian children.

This study was conducted in the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology at one of the India's largest Paediatric tertiary care centre. We did a retrospective analysis of prospectively well-maintained outpatient and inpatient data on children (≤ 18 years) with genetically confirmed ABCB4 mutations, including homozygous, compound HET, and HET variants, diagnosed between January 2021 and March 2025. Children (≤ 18 years) with clinically suspected cho

Decompensation/ESLD was defined as the presence of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and/or gastrointestinal bleeding. Oesophageal varices were classified as small or large according to the Baveno VI consensus guidelines[8]. Disease status at last follow-up was categorized as: (1) Improved: Resolution of jaundice and amelioration of portal hypertension and biochemistries; (2) Stable: No further deterioration in liver function tests (LFTs) or coagulation parameters; and (3) Worsened: Development of new signs or symptoms of portal hypertension, uncorrectable co

As per unit protocol, patients underwent relevant investigations at the time of admission, including a complete blood count, LFT with GGT, serum bile acids, and a coagulation profile. Investigations, such as LFT and coagulation pa

Clinical details, laboratory investigations, and other relevant data were recorded using a structured proforma. Cases were stratified based on mutation status, into homozygous/compound HET and HET groups, which were subsequently analyzed and compared. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained prior to the commencement of the study (No. IEC-INT/2023/DM-1452).

Descriptive statistics were calculated, with data presented as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, or as %, as appropriate. Comparisons between patients with homozygous/compound HET and HET ABCB4 mutations, as well as between those with and without disease progression, were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Cases with missing information were retained in the analysis when the absent variables had no impact on the assessment of study outcomes. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 27, with a two-tailed P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

A total of 26 patients (61.5% male) with ABCB4 mutations were included during the study period: (1) 14 with ho

This group comprised 16 children (11, 68.75% male); 14 were homozygous and 2 were compound HET. The median age at symptom onset and presentation was 54 months (range: 4-168 months), and 60 months (range: 4-172 months), respectively. Consanguinity was documented in 37.5% of cases, while 75% had a family history of liver disease and/or gallstone disease. At presentation, 7 patients (43.8%) had clinical signs of liver decompensation. Fifteen patients underwent upper gas

| Parameters | Homozygous/compound HET mutation | HET mutation (n = 10) | P value |

| General characteristics | |||

| Male gender | 62.5% | 60% | 1.00 |

| Median age at symptom onset in months | 54 (4, 168) | 10.5 (5, 72) | 0.40 |

| Median age at presentation in months | 60 (4, 172) | 18 (11, 126) | 0.42 |

| Consanguinity | 37.5% | 10% | 0.19 |

| Positive family history | 75% | 30% | 0.04 |

| Sibling loss | 43.8% | 33.3% | 0.69 |

| Anthropometry | |||

| Weight Z-score at admission | -1.09 (-2.03, -0.21) | -1.39 (-2.61, 0.10) | 0.97 |

| Height Z-score at admission | -0.91 (-2.72, -0.52) | -2.1 (-3.33, 0.03) | 0.57 |

| Weight Z-score at last follow up | -0.42 (-1.29, -0.125) | -0.58 (-1.63, 1.31) | 0.90 |

| Height Z-score at last follow up | -0.37(-1.83, 0.33) | -0.76 (-2.23, 0.91) | 0.86 |

| Clinical parameters at admission | |||

| Jaundice | 68.8% | 90% | 0.35 |

| Pruritus | 68.8% | 80% | 0.66 |

| Ascites | 43.2% | 0% | 0.02 |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 12.5% | 0% | 0.5 |

| Decompensation at admission | 43.8% | 0% | 0.02 |

| Esophageal varix | 0.009 | ||

| No varix | 20% | 87.5% | |

| Small varix | 40% | 12.5% | |

| Large varix | 40% | 0 | |

| Genetics | |||

| Missense variants | 81.3% | 80% | 1.00 |

| Recent American College of Medical Genetics class likely pathogenic or pathogenic | 100% | 30% | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| First visit | |||

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 162 (64, 230) | 415 (167, 577) | 0.007 |

| TB (mg/dL) | 2.58 (1.6, 6.7) | 3.84 (1.59, 8.27) | 0.56 |

| DB (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.71, 4.1) | 2.15 (1.08, 4.14) | 0.59 |

| AST (U/L) | 198 (116, 287) | 124.5 (90.75, 238) | 0.29 |

| ALT (U/L) | 120 (64, 201) | 64.5 (37.25, 118.25) | 0.06 |

| ALP (U/L) | 318 (280, 550) | 296 (205.25, 384) | 0.15 |

| GGT (U/L) | 171 (94, 450) | 38 (17, 148.5) | 0.007 |

| Prothrombin time | 76 (57.5, 100) | 100 (88, 100) | 0.12 |

| INR | 1.27 (1, 1.58) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) | 0.10 |

| Bile acids (µmol/L) | 139.5 (33.4, 174.2) | 206 (80, 335) | 0.24 |

| At last visit | |||

| TB (mg/dL) | 3.84 (0.94, 15.09) | 0.42 (0.28, 2.65) | 0.003 |

| DB (mg/dL) | 1.87 (0.33, 8.36) | 0.09 (0.09, 1.9) | 0.007 |

| AST (U/L) | 247 (106.7, 462.2) | 41 (35.2, 110.2) | 0.004 |

| ALT (U/L) | 131 (53.5, 140.5) | 33 (25.4, 55.5) | 0.003 |

| ALP (U/L) | 329 (176, 719) | 265 (169.5, 461) | 0.61 |

| GGT (U/L) | 146 (95, 310) | 11 (10.25, 13.5) | 0.003 |

| INR | 1.20 (1.08, 1.69) | 1.02 (1, 1.16) | 0.01 |

| Total duration of follow up in months | 28.5 (3.7, 59) | 23 (11.7, 60) | 0.61 |

| Outcomes | 31.3% | 20% | 0.66 |

| Progressive disease (death, decompensated disease, uncorrectable coagulopathy at last follow-up) | 68.8% | 20% | 0.01 |

| Mortality | 31.3% | 20% | 0.34 |

| Patient | Gender | Age at symptom onset (months) | Age at first presentation (months) | Consanguinity | Family history | Anthropometry (weight/height) | Clinical features | Disease status at presentation | Esophageal varix | Type of ABCB4 mutation | Disease status at last follow-up | Issues at last follow up | Final outcome at last follow-up |

| P1 | Male | 22 | 24 | Yes | Yes | -0.34Z, -0.55Z | HSM | C | Small varix | Homozygous | S | PH | Alive |

| P2 (sibling of P1) | Male | 6 | 60 | Yes | Yes | 0.21Z, -0.52Z | J, P, HSM | C | Large varix | Homozygous | S | PH | Alive |

| P3 | Male | 6 | 9 | No | Yes | NA | HSM, P | C | No varix | Homozygous | W | PH, INR > 1.5 | Alive |

| P4 | Male | 6 | 24 | No | No | -1.42Z, -0.87Z | P, HSM | C | No varix | Homozygous | S | Alive | |

| P5 | Male | 96 | 96 | No | Yes | -0.17Z, 0.09Z | A, HSM | D | Large varix | Homozygous | S | PH, recurrent acute kidney injury and nephrotic range proteinuria | Alive |

| P6 (sibling of P5) | Female | 168 | 172 | No | Yes | -0.75Z, -1.11Z | J, P, A, HSM, E, B | D | Large varix | Homozygous | W | PH, INR > 1.5 | Expired post LT (primary graft non-function) |

| P7 | Male | 120 | 120 | Yes | Yes | -3.59Z, -2.70Z | J, P, A, HSM | C | Large varix | Homozygous | W | PH, INR > 1.5, E | Expired after 3 years of (LT (acute rejection) |

| P8 | Female | 58 | 60 | No | No | 0.06Z, -0.72Z | J, P, HSM, A, B | D | Small varix | Homozygous | W | INR > 1.5 | Alive |

| P9 | Female | 6 | 48 | No | Yes | -2.9Z, -2.72Z | J, P, HSM | C | Small varix | Homozygous | W | PH, E | Expired |

| P10 (sibling of P9) | Male | 12 | 34 | No | Yes | -2.5Z, -3.14Z | J, P, HSM | C | Large varix | Homozygous | W | PH | Alive |

| P11 | Female | 84 | 108 | Yes | Yes | -0.02Z, -0.91Z | J, P, A, HSM | D | Small varix | Homozygous | W | PH, INR > 1.5, MRCP-sclerosing cholangitis | Expired |

| P12 | Female | 120 | 144 | No | Yes | NA | J, HSM | C | Small varix | Homozygous | W | PH, B, INR > 1.5 | Alive |

| P13 | Male | 60 | 60 | Yes | Yes | -1.36Z, -3.46Z | J, A, HSM | D | Small varix | Homozygous | S | Alive | |

| P14 | Male | 80 | 83 | No | No | -0.77, 0.35 | J, P | C | Large varix | Homozygous | W | PH, INR > 1.5 | Alive |

| P15 | Male | 4 | 4 | No | Yes | NA | J, HSM | C | Not done | Compound HET | W | PH, INR > 1.5, E, acute-on-chronic liver failure | Expired |

| P16 | Male | 50 | 52 | No | No | -1.94Z, -3.07Z | P, HSM, A | D | No varix | Compound HET | S | Nephrotic range proteinuria (carries additional X-linked FLNA mutation) | Alive |

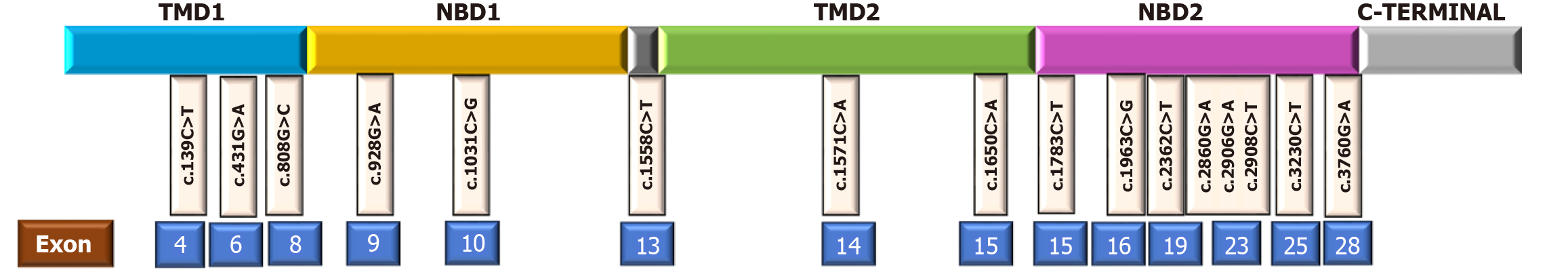

Clinical details of individual patients with bi-allelic mutations are presented in Table 2, and their genetic mutations, along with their pathogenicity, are listed in Table 3. Among the 16 patients with bi-allelic mutations, a total of 18 variants were identified, of which 81.3% were missense mutations (Table 3 and Figure 1).

| Patient | Zygosity | Exon number | Mutation | Predicted effect | Domain | Type of mutation | Polyphen | SIFT | Mutation taster | GnomAD1 | Updated ACMG class | ACMG criteria |

| P1 | Ho | 23 | c.2908T>C | p.Phe970Leu | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P2 (sibling of P1) | Ho | 23 | c.2908T>C | p.Phe970Leu | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P3 | Ho | 23 | c.2908T>C | p.Phe970Leu | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P4 | Ho | 23 | c.2908T>C | p.Phe970Leu | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P5 | Ho | 23 | c.2860G>A | p.Gly954Ser | Linker (NBD2 adjacent) | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP5 |

| P6 (sibling of P5) | Ho | 23 | c.2860G>A | p.Gly954Ser | Linker (NBD2 adjacent) | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP5 |

| P7 | Ho | 23 | c.2860G>A | p.Gly954Ser | Linker (NBD2 adjacent) | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP5 |

| P8 | Ho | 23 | c.2860G>A | p.Gly954Ser | Linker (NBD2 adjacent) | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP5 |

| P9 | Ho | 4 | c.139C>T | p.Arg47Ter | TMD1 | NONSENSE | - | - | DC | 0 | P | PVS1, PS4, PM2 |

| P10 (sibling of P9) | Ho | 4 | c.139C>T | p.Arg47Ter | TMD1 | NONSENSE | - | - | DC | 0 | P | PVS1, PS4, PM2 |

| P11 | Ho | 25 | c.3230C>T | p.Thr1077Met | NBD2 | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0.005 | LP | PP2, PP3, PM3 |

| P12 | Ho | 28 | c.3760G>A | p.Gly1254Ser | NBD2 | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PP2, PP3, PM3 |

| P13 | Ho | 15 | c.1783C>T | p.Arg595Ter | NBD2 start | NONSENSE | D | D | DC | 0.001 | P | PVS1, PM2, PP5 |

| P14 | Ho | 6 | c.431G>A | p.Arg144Gln | - | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0.0007 | LP | PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3 |

| P15 | Co HET | 10 | c.1031C>G | p.Ala344Gly | NBD1 | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PM2, PP2 |

| 19 | c.2362C>T | p.Arg788Trp | NBD2 | MISSENSE | PossD | D | DC | 0.016 | LP | PM2, PP2 | ||

| P16 | Co HET | 15 | c.1783C>T | p.Arg595Ter | NBD2 start | NONSENSE | D | D | DC | 0.001 | P | PVS1, PM2, PP5 |

| 23 | c.2906G>A | p.Arg969His | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | - | Polymorphism | 0.0001 | LP | PM2, PP2 |

Missense mutations: Patients with the homozygous p.Phe970Leu variant (P1-P4) had infantile onset (mean, 10 months) but maintained compensated disease, consistent with minimal ATPase disruption from this moderately conserved domain variant.

Patients with the homozygous p.Gly954Ser variant (P5-P8) had a later onset (111 ± 39 months) but rapid progression and poor outcomes despite treatment. The variant, in a conserved domain, likely disrupts adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding and folding; two patients died, others developed uncorrectable coagulopathy, with some (P5 and P7) initially misdiagnosed as AIH.

Patients P11, 12, and 14 also had (different) missense mutations located in the highly conserved segments of ABCB4 (Figure 1) with overall poor outcomes (Tables 2 and 3).

Nonsense mutations: Siblings P9 and P10 with nonsense homozygous p.Arg47Ter mutations also had poor clinical outcomes. P13 with nonsense homozygous p.Arg595Ter mutation presented with decompensated CLD (Tables 2 and 3).

Compound HET mutations: Patients P15 and P16 carried compound HET ABCB4 mutations with features as described in Tables 2 and 3.

Follow-up: The group 1 patients were followed up for a median duration of 28.5 months (range: 2-124 months). All received standard-of-care management, including UDCA. Two patients (P4 and P9) required adjunctive rifampicin for intractable pruritus. Two-thirds of the patients from this group had disease worsening at the last follow-up, with one-third of patients succumbing to the disease (Tables 1 and 2).

Ten children with HET ABCB4 mutations were identified during the study period. Their clinical features, laboratory parameters, and genetic variants are detailed in Tables 4 and 5. Most of them presented with cholestasis in infancy, with resolution in follow-up (P18, P19, P21, P22, P25, P26). One had a history of recurrent jaundice (P20), but overall a fa

| Patient | Gender | Age at symptom onset (months) | Age at first presentation (months) | Consanguinity | Family history | Anthropometry (weight/height) | Clinical features | Disease status at presentation | Esophageal varix | Disease status at last follow-up | Issues at last follow up/salient features | Final outcome at last follow- up |

| P17 (sibling of P3) | Female | 180 | 180 | No | Yes | 0.73Z, 0.87Z | H | C | No | S | Screening detected | Alive |

| P18 (sibling of P15) | Female | 5 | 17 | No | Yes | -0.46Z | J, P, H | C | Not done | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| P19 | Male | 5 | 19 | No | Yes | -2.33Z, -4.06Z | J, P, HSM | C | No varix | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| P20 | Female | 48 | 72 | No | No | 0.1Z, 0.1Z | J, P, H | C | No varix | I | Recurrent jaundice | Alive |

| P21 | Male | 1 | 3 | No | No | -3.43Z, -2.15Z | J, P, HSM | C | No varix | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| P22 | Male | 8 | 8 | No | No | -3.2Z, -2.54Z | J, P, HSM | C | No varix | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| P23 | Male | 144 | 192 | No | No | -2.42Z, -3.33Z | J, P, HSM | C | Large varix | W | PH, B, A, E, MRCP-sclerosing cholangitis | Expired |

| P24 | Female | 48 | 108 | No | No | -2.39Z, -3.34Z | J, P, HSM | C | Small varix | W | PH, E, SNHL, additional heterozygous mutations in GJB6 and SPTB (both autosomal dominant) | Expired |

| P25 | Male | 11 | 13 | No | No | -0.34Z, -1.63Z | J, P, H | C | Not done | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| P26 | Male | 10 | 12 | No | No | 0.11Z, -0.04Z | J, P, HSM | C | No varix | I | Infantile onset, self-limiting course | Alive |

| Patient | Zygosity | Exon Number | Mutation | Predicted effect | Domain | Type of mutation | Polyphen | SIFT | Mutation taster | GnomAD1 | Updated ACMG class | ACMG criteria |

| P17 (sibling of P3) | HET | 23 | c.2908T>C | p.Phe970Leu | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | D | DC | 0 | VUS | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P18 (sibling of P15) | HET | 19 | c.2362C>T | p.Arg788Trp | NBD2 | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0.016 | VUS | PM2, PP2 |

| P19 | HET | 8 | c.808G>C | p.Gly270Arg | TMD1/NBD1 boundary | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0.189 (THRESHOLD:0.1) | VUS | PS1, PP2, PP3, BS1 |

| P20 | HET | 8 | c.808G>C | p.Gly270Arg | TMD1/NBD1 boundary | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0.189 (THRESHOLD:0.1) | VUS | PS1, PP2, PP3, BS1 |

| P21 | HET | 16 | c.1963C>G | p.Pro655Ala | NBD2 | MISSENSE | B | - | Polymorphism | 0 | VUS | PP2 |

| P22 | HET | 14 | c.1571C>A | p.Thr524Asn | TMD2 | MISSENSE | ProbD | D | DC | 0 | LP | PS4, PM2, PP3, PP2 |

| P23 | HET | 9 | c.928G>A | p.Ala310Thr | NBD1 | MISSENSE | PossD | - | - | - | VUS | - |

| P24 | HET | 13 | c.1558C>T | p.Gln520Ter | Linker before TMD2 | NONSENSE | - | - | - | 0.0001 | LP | PVS1, PM2 |

| P25 | HET | 15 | c.1650C>A | p.Asn550Lys | TMD2 | MISSENSE | PossD | D | - | 0.0004 | VUS | PM1, PM2, PP2 |

| P26 | HET | 15 | c.1783C>T | p.Arg595Ter | NBD2 start | NONSENSE | - | - | DC | 0.001 | Pathogenic | PVS1, PM2, PP5 |

Children with older age at onset and poor outcome: Two patients (P23 and P24) had a steady worsening despite car

Patient P23 (HET p.Ala310Thr) had progressive disease leading to death. This NBD1 variant likely impairs ATP binding and transport; initial treatment for autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis yielded no response to immunosuppressants or UDCA. Patient P24 (HET p.Gln520Ter) presented with compensated CLD and portal hypertension at 108 months but died within a year (Table 4).

Follow-up: The patients in group 2 had a median follow-up duration of 23 months (range, 3-129 months). All received UDCA, with most showing an overall favourable response; however, both patients presenting at an older age died (Table 4).

Demographic characteristics, clinical features and complications, liver histopathology, variant pathogenicity, and overall outcomes were compared between the two groups (Table 1).

Family history of liver disease and/or gallstone disease, decompensated liver disease, proportion of larger varices, median GGT and proportion of patients carrying pathogenic/Likely pathogenic mutations were significantly higher in group 1 (Table 1). Patients in group 2 showed improvement in LFTs in follow-up, with significantly fewer patients developing progressive disease (Table 1). Given the limited sample size of this cohort, the statistically significant P values reported in Table 1 should be interpreted as indicative of strong clinical trends rather than definitive evidence, and they require validation in larger studies.

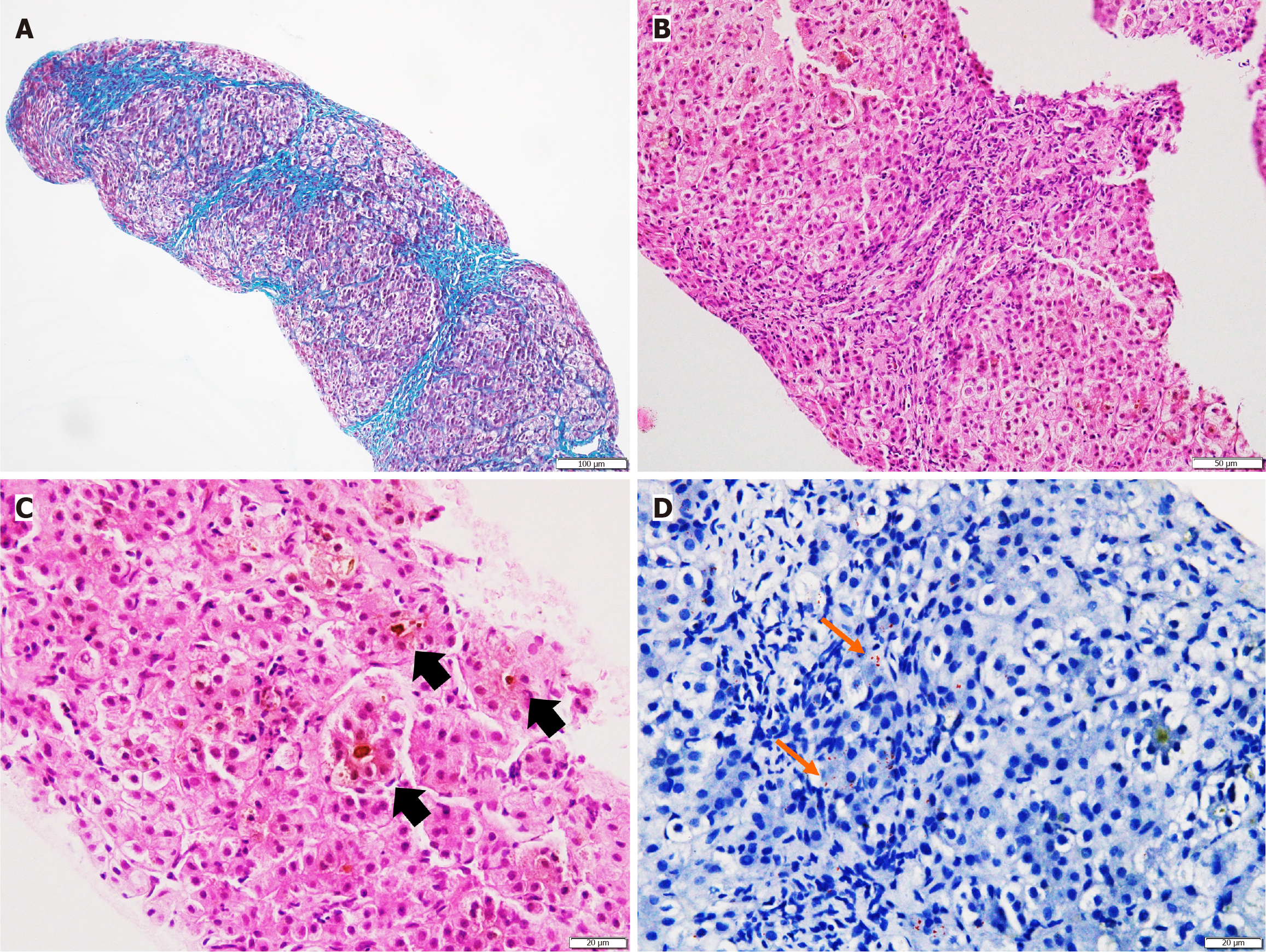

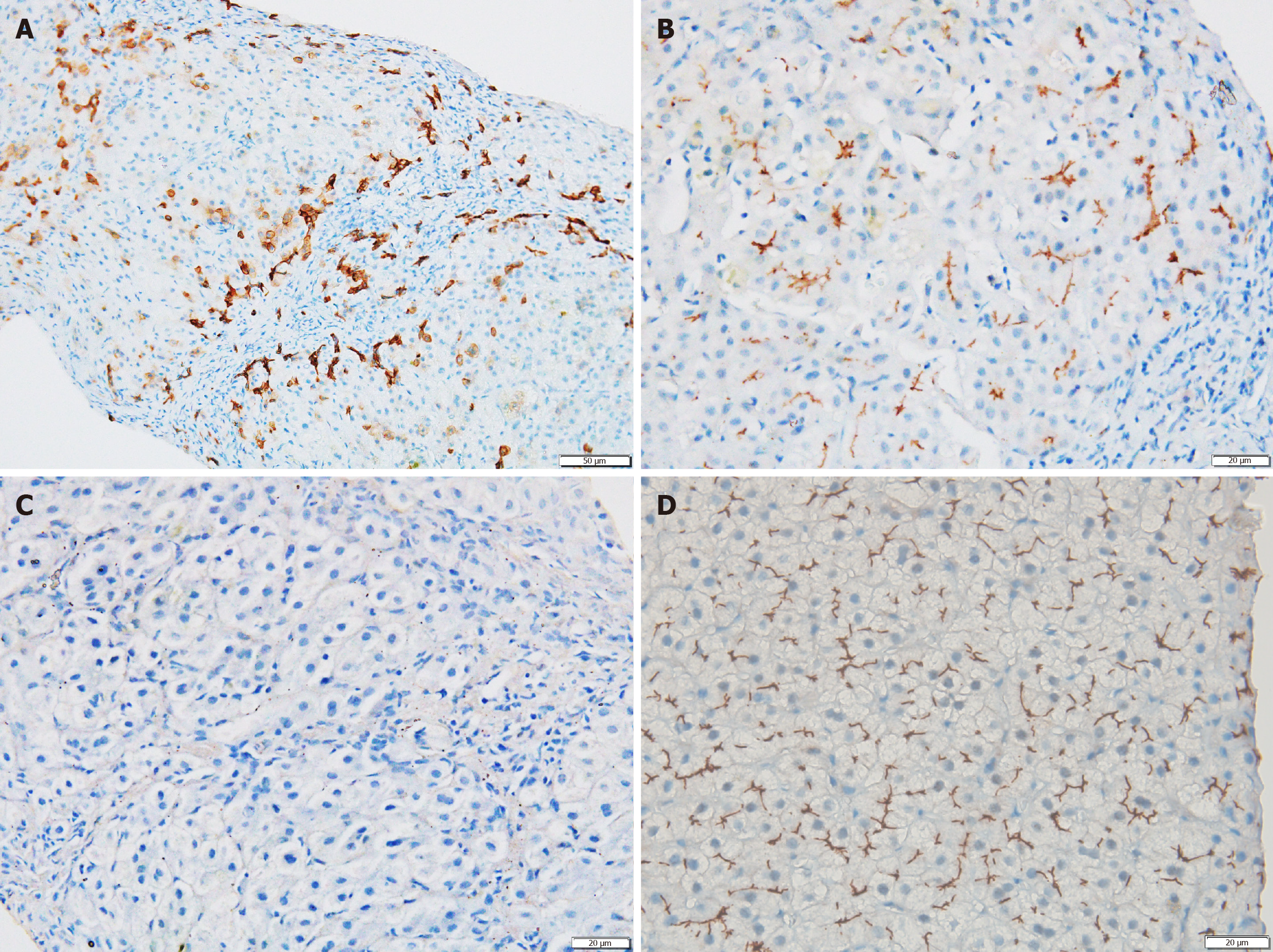

Liver biopsy was performed in 25 patients. Histopathology findings did not differ significantly between the two groups (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4). MDR3 immunostaining was performed in 11 patients overall (in both groups), with nine showing negative staining; no intergroup differences were noted (Figure 3). Sixteen (61.5%) of histopathology samples were subjected to Rhodanine staining, of which twelve patients (75%: 10 biallelic and 2 monoallelic) had Rhodanine staining positivity (Figure 2D), indicating copper excess.

PFIC3 is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by cholestasis and a highly variable clinical presentation and prognosis. Biallelic mutations in ABCB4 typically result in complete MDR3 deficiency, often leading to ESLD during childhood. However, HET missense variants in ABCB4 have been implicated in symptomatic cholestasis, thereby complicating the approach and management. NGS has helped to understand the genetic basis of cryptogenic CLD. In this context, we present our experience with pediatric patients harbouring both monoallelic and biallelic ABCB4 mutations.

Our cohort included 16 patients with biallelic ABCB4 mutations. Their clinical features and LFT profiles were largely consistent with previous studies (Table 6)[12-15]. The median age at symptom onset in our cohort was higher than that in earlier reports. However, a review of 118 cases of PFIC3 noted a mean age of disease onset of 6.5 years, with 58.4% of patients experiencing symptoms before 60 months of age, similar to that in our cohort[16].

| Ref. | Year/country | Number of patients | Median age at onset of symptoms (months) | Median Age at presentation (years) | Pruritus (%) | Jaundice (%) | Hepatomegaly (%) | Splenomegaly (%) | Variants with missense mutation (%) | Laboratory parameters | |||

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (IU/L) | Alanine aminotransferse (IU/L) | Aspartate aminotransferse (IU/L) | Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||||||||

| Schatz et al[12] | 2018/Germany | 26 | 5 | 4.8 | 100 | 61.5 | 84.6 | 96.1 | 77.1 | 320 | 212 | ||

| Chen et al[13] | 2022/China | 13 | 36 | - | 30.7 | 53.8 | 100 | 77 | 61.5 | 197 | 130 | 1.1 | |

| Al-Hussaini et al[14] | 2021/Saudi Arabia | 25 | 10 | 2 | 92 | 12 | 80 | - | 81.4 | 202 | 149 | 1.27 | |

| Gonzales et al[15] | 2023/France | 38 | 11 | 3.3 | 79 | 29 | 82 | 68 | 71 | 150 | - | 0.73 | |

| Index study | 2025/India | 16 | 54 | 5 | 68.8 | 68.8 | 100 | 81.2 | 81.3 | 171 | 120.5 | 198 | 2.58 |

Our cohort replicates the typical presentation of biallelic ABCB4 mutations as classical PFIC3, which often progresses to ESLD. At presentation, nearly half of our patients had ascites and decompensation. Despite supportive therapy and UDCA, disease progression occurred in 68.8% of patients till the last follow-up (Table 1). Other pediatric studies have documented progression to ESLD and the need for LT in roughly 17%-50% of cases, highlighting the severity and rapid progression of the disease in children[12,13,15,17,18].

Prior to the widespread use of genomic sequencing, liver histopathology with IHC for MDR3 was used to diagnose PFIC3. Histological findings in PFIC3 typically include higher grades of portal-based fibrosis and ductular reaction, accompanied by mild to moderate lobular and portal inflammatory infiltrates – features that were consistently observed in our cohort and have been similarly reported in multiple studies (Figure 2)[14,15,18].

The absence of MDR3 staining on IHC serves as a distinguishing feature of PFIC3 compared to other PFIC subtypes. In our study, 9 of 11 patients in whom IHC was done demonstrated negative MDR3 staining (Figure 3). A complete absence of staining is usually seen in patients with biallelic null variants, while those with missense or monoallelic mutations demonstrate faint or even preserved MDR3 expression. This pattern has been corroborated by Gonzales et al[15] and Jacquemin et al[19]. Though absent MDR3 staining in null variants alone is expected, we noted absent staining in missense mutations also. This absence has been attributed to intracellular misprocessing of MDR3 and the nature of the missense mutation. Mutations in highly conserved areas may prevent MDR3 expression[19]. Most mutations in our cohort were located in such domains. (Tables 3 and 5). Weng et al[20] observed in their cohort that missense variants had similar levels of MDR3 protein compared to wild-type, except in one case, demonstrating the variability in MDR3 expression, which can explain the poor reliability of MDR3 IHC.

AIH and WD remain the most common etiologies of pediatric CLD in our region[21,22]. Before the genetic diagnosis, some of our patients received treatment for AIH. Positive Rhodanine staining on histopathology further complicates the diagnosis, given the higher prevalence of WD compared to ABCB4 mutations in patients with CLD requiring hospitalisation. The presence of pruritus, early onset portal hypertension with varices, elevated GGT, and IHC findings for MDR3, as well as a poor or absent response to standard therapies for AIH or WD, raised the suspicion of PFIC3, leading to a genetic workup.

Missense mutations were the most common in our study, which is similar to a systematic review of 118 patients with PFIC3, in which missense variants accounted for 76.9% of all mutations[16]. The nature of the mutation, the resultant protein alteration, and the affected functional domain seem to be critical determinants of disease severity and pro

Few variants had unique clinical phenotypes. Homozygous p.Phe970Leu mutation affects a moderately conserved domain and is predicted to cause minimal disruption to ATPase function, which may explain the slower disease progression observed in our cohort compared to other homozygous mutations. The same variant has been described in a Saudi Arabian cohort, which reported a similarly indolent course[14]. Interestingly, all patients in our cohort with this specific mutation originated from the Kashmir Valley, suggesting a potential regional or ethnic clustering. Factors such as ancient human migration, endogamy, and founder effects in geographically or culturally isolated populations like those in Kashmir may contribute to this phenomenon.

The homozygous p.Phe954Ser mutation affects a highly conserved domain with a direct role in ATP binding and protein folding, thereby contributing significantly to disease severity[19,23]. Delaunay et al[3] previously reported a compound HET presentation of this variant in two patients who developed cholestasis, icterus, and hepatomegaly at the age of four years. One of these individuals required LT at 21 years of age, while the other maintained native liver function up to 18 years. After functional characterization, this variant was classified as a class III mutation, i.e. impaired activity without major effects on protein maturation[3]. However, our patients had pure homozygous mutations, which would probably significantly affect protein activity, thereby leading to rapid progression. Gonzales et al[15] also described this variant in two patients, one of whom required LT while the other did not, similar to the variable disease course in our cohort. This can be attributed to undetected genetic variations in other hepatocanalicular transporter genes, hormonal factors, or environmental exposures[13].

The rapid disease progression observed in our patients with nonsense mutations is consistent with the known mechanism of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, which leads to the elimination of protein expression[19]. The localisation of variants within NBDs (Figure 1, Tables 3 and 5), which are evolutionarily conserved and functionally critical, likely accounts for the progressive disease course observed in affected individuals[24]. A functional characterization of these mutations (as performed by Delaunay et al[3]) could have explained the phenotypic variability, but was not performed in our cohort. A proteomics study by Guerrero et al[25] demonstrated that, irrespective of the type of homozygous mutation, there is disturbed phosphorylation of certain residues in MDR3 protein, thereby affecting the binding or hydrolysis of ATP, which is crucial for phosphatidyl choline translocation. There is an upregulation of class I and II HLA, along with immunoglobulins and tumor necrosis factor alpha, in PFIC 3 livers, emphasising a proinflammatory and profibrogenic state. There is also an impairment in tight and adherens junctions, along with the reconfiguration of the actin-myosin microfilament network, in PFIC3 hepatocytes, which affects cell polarity. Weng et al[20] showed reduced pho

The reason why heterozygotes present clinically remains a matter of debate. HET ABCB4 variants are increasingly recognized as clinically relevant in pediatric cholestatic liver diseases. In our cohort, monoallelic ABCB4 mutations were identified in 10 children, accounting for 40% of all ABCB4 mutation-positive cases. These findings highlight the possible pathogenic potential of HET variants, which were previously regarded as benign or of uncertain significance.

The clinical spectrum among these patients was heterogeneous, ranging from transient infantile cholestasis to progressive liver disease and portal hypertension. Such clinical heterogeneity in patients with monoallelic ABCB4 mutations may be attributed to functional heterogeneity, as described by Gordo-Gilart et al[26] who noted reduced MDR3 protein levels, intracellular retention of the protein in the endoplasmic reticulum, and a decrease in phosphatidylcholine efflux activity to 18%-56% of normal.

Most patients experienced a self-limited cholestatic course and recurrent jaundice without progression, with normalization of liver biochemistry following treatment with UDCA (Table 4). This observation aligns with the findings of Hegarty et al[27], who reported that 48% of patients with monoallelic variants achieved long-term biochemical normalization and were subsequently discharged from follow-up.

One patient with a novel protein-truncating HET p.Gln520Ter mutation demonstrated absent MDR3 expression and experienced rapid clinical deterioration (Tables 4 and 5). Truncating variants located within transmembrane domains may lead to more severe disease phenotypes, even in HET carriers, due to their critical role in MDR3 function, as ob

Two patients had MRCP features of sclerosing cholangitis. The coexistence of primary sclerosing cholangitis-like features and ABCB4 mutation has been previously reported in adults. These findings support the hypothesis that ABCB4 may act as a susceptibility gene modifier in immune-mediated cholangiopathies[28-32]. Hegarty et al[27] reported cholangiopathy on axial imaging in four patients with monoallelic ABCB4 mutations, attributing this to chronic alterations in bile composition that damage the biliary epithelium. This mechanism was further supported in an animal model study. Bile regurgitation from leaky ducts into the portal tracts initiates periductal inflammation and activates periductal fibrogenesis. Over time, this cascade leads to obliterative cholangitis, resulting from the atrophy and death of bile duct epithelial cells[33].

The reason why heterozygotes present clinically remains a matter of debate. The variant may result in an altered protein, which could interfere with the function of the wild-type gene product. A truncating monoallelic mutation may leave the wild-type allele incapable of producing a sufficient quantity of protein to sustain a normal phenotype. It is also possible that a second mutation is not picked up by conventional NGS. In some cases, the mutant protein may alter the behaviour of other common diseases.

The long-term implications of monoallelic ABCB4 variants extend into adulthood, with established associations with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis, drug-induced liver injury, primary sclerosing cholangitis and even cholangiocarcinoma[28,29,34-36]. According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommendations, we plan to follow up these children at risk at regular intervals (3-6 months) with serial bio

The difference in clinical course between those with bi-allelic and monoallelic mutations was expected, as bi-allelic mutations cause a significant reduction in functional MDR3 protein, resulting in severe disease with early progression. Response to treatment also varies, as those with bi-allelic mutations continued to have worsening liver functions despite continuing on UDCA, as observed by Wang et al[16] in their systematic review. The role of Rifampicin and bile acid sequestrants, such as cholestyramine, is not well studied. Few experimental medications focusing on class II mutations, which exhibit trafficking defects with intracellular retention, have been studied, including ABCC7/CFTR correctors and structural analogues of roscovitine, but they are still in the early phases of trial[38]. Drugs with chaperone-like activity, such as curcumin and 4-phenylbutyric acid, are proposed to enhance the targeting of misfolded and intracellularly trapped mutant proteins to the plasma membrane, leading to increased phospholipid efflux activity[39,40]. LT is the only effective treatment for ESLD.

This is the first and largest pediatric series from a major tertiary care centre that comprehensively characterises a sizable, well-phenotyped cohort of Indian children with ABCB4 mutations, a population for which such data are scarce. The inclusion and comparative analysis of both biallelic and monoallelic cases provide important clinical insights. The attempt to correlate specific genotypes (e.g., p.Phe970Leu, p.Gly954Ser) with clinical outcomes, including the observation of potential regional clustering, is a significant contribution to the field. The clinical relevance of HET mutations with variable presentations underscores the importance of prospective monitoring to identify the evolving spectrum of liver manifestations in this population. The integration of histopathology (including Rhodanine staining) and genetics to differentiate from WD and AIH is clinically very relevant.

As it was a single-centre, retrospective study, the sample size was small and consequently had low statistical power for group comparisons. Hence, the comparison has to be interpreted with caution. There is a potential selection bias, as the cohort is from a tertiary referral centre, likely seeing more severe cases. Parental and sibling genetic testing were not performed, limiting our ability to confirm inheritance patterns and zygosity, which would have strengthened the interpretation of variant pathogenicity. In monoallelic cases, there is a possibility of undetected second-hit mutations in non-coding regions or complex structural variations. Functional validation of the identified ABCB4 variants was not undertaken, which could have provided deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed phenotypes.

ABCB4 mutations, in both homozygous and HET states, are a significant cause of pediatric liver disease often misclassified as cryptogenic CLD, AIH, or WD. Clinical clues include pruritus, elevated GGT, early portal hypertension, and limited response to standard therapy, which should lead to genetic testing. Biallelic truncating or severe missense variants usually progress, whereas monoallelic, mild missense variants respond to therapy but still need long-term surveillance; monoallelic truncating or conserved-region variants may advance to ESLD. Early diagnosis, genotype-guided management, and family screening are central to patient care. Larger prospective studies with family segregation and functional assays are needed to better define genotype-phenotype associations and guide management.

| 1. | Srivastava A. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:25-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vinayagamoorthy V, Srivastava A, Sarma MS. Newer variants of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:2024-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Delaunay JL, Durand-Schneider AM, Dossier C, Falguières T, Gautherot J, Davit-Spraul A, Aït-Slimane T, Housset C, Jacquemin E, Maurice M. A functional classification of ABCB4 variations causing progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3. Hepatology. 2016;63:1620-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reichert MC, Lammert F. ABCB4 Gene Aberrations in Human Liver Disease: An Evolving Spectrum. Semin Liver Dis. 2018;38:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sundaram SS, Sokol RJ. The Multiple Facets of ABCB4 (MDR3) Deficiency. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2007;10:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Deleuze JF, Jacquemin E, Dubuisson C, Cresteil D, Dumont M, Erlinger S, Bernard O, Hadchouel M. Defect of multidrug-resistance 3 gene expression in a subtype of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology. 1996;23:904-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ziol M, Barbu V, Rosmorduc O, Frassati-Biaggi A, Barget N, Hermelin B, Scheffer GL, Bennouna S, Trinchet JC, Beaugrand M, Ganne-Carrié N. ABCB4 heterozygous gene mutations associated with fibrosing cholestatic liver disease in adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:131-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2609] [Cited by in RCA: 2361] [Article Influence: 214.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Biswal S, Biswas D, Mahalik SK, Purkait S, Mitra S. Assessment of Matrix Metalloprotease - 7 (MMP7) Immunohistochemistry in Biliary Atresia and Other Pediatric Cholestatic Liver Diseases. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2024;43:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ayyanar P, Mahalik SK, Haldar S, Purkait S, Patra S, Mitra S. Expression of CD56 is Not Limited to Biliary Atresia and Correlates with the Degree of Fibrosis in Pediatric Cholestatic Diseases. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2022;41:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vij M, Safwan M, Shanmugam NP, Rela M. Liver pathology in severe multidrug resistant 3 protein deficiency: a series of 10 pediatric cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schatz SB, Jüngst C, Keitel-Anselmo V, Kubitz R, Becker C, Gerner P, Pfister ED, Goldschmidt I, Junge N, Wenning D, Gehring S, Arens S, Bretschneider D, Grothues D, Engelmann G, Lammert F, Baumann U. Phenotypic spectrum and diagnostic pitfalls of ABCB4 deficiency depending on age of onset. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:504-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen R, Yang FX, Tan YF, Deng M, Li H, Xu Y, Ouyang WX, Song YZ. Clinical and genetic characterization of pediatric patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 (PFIC3): identification of 14 novel ABCB4 variants and review of the literatures. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17:445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Al-Hussaini A, Lone K, Bashir MS, Alrashidi S, Fagih M, Alanazi A, AlYaseen S, Almayouf A, Alruwaithi M, Asery A. ATP8B1, ABCB11, and ABCB4 Genes Defects: Novel Mutations Associated with Cholestasis with Different Phenotypes and Outcomes. J Pediatr. 2021;236:113-123.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Gonzales E, Gardin A, Almes M, Darmellah-Remil A, Seguin H, Mussini C, Franchi-Abella S, Duché M, Ackermann O, Thébaut A, Habes D, Hermeziu B, Lapalus M, Falguières T, Combal JP, Benichou B, Valero S, Davit-Spraul A, Jacquemin E. Outcomes of 38 patients with PFIC3: Impact of genotype and of response to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang S, Liu Q, Sun X, Wei W, Ding L, Zhao X. Identification of novel ABCB4 variants and genotype-phenotype correlation in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3. Sci Rep. 2024;14:27381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cao L, Ling X, Yan J, Feng D, Dong Y, Xu Z, Wang F, Zhu S, Gao Y, Cao Z, Zhang M. Clinical and genetic study of ABCB4 gene-related cholestatic liver disease in China: children and adults. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Colombo C, Vajro P, Degiorgio D, Coviello DA, Costantino L, Tornillo L, Motta V, Consonni D, Maggiore G; SIGENP Study Group for Genetic Cholestasis. Clinical features and genotype-phenotype correlations in children with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 related to ABCB4 mutations. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:73-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jacquemin E, De Vree JM, Cresteil D, Sokal EM, Sturm E, Dumont M, Scheffer GL, Paul M, Burdelski M, Bosma PJ, Bernard O, Hadchouel M, Elferink RP. The wide spectrum of multidrug resistance 3 deficiency: from neonatal cholestasis to cirrhosis of adulthood. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1448-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Weng YH, Zheng YF, Yin DD, Xiong QF, Li JL, Li SX, Chen W, Yang YF. Clinical, genetic and functional perspectives on ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 4 variants in five cholestasis adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:104975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 21. | Vinayagamoorthy V, Srivastava A, Anuja AK, Agarwal V, Marak R, Sarma MS, Poddar U, Yachha SK. Biomarker for infection in children with decompensated chronic liver disease: Neutrophilic CD64 or procalcitonin? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2024;48:102432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ravindranath A, Srivastava A, Yachha SK, Poddar U, Sarma MS, Mathias A. Prevalence and Precipitants of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Hospitalized Children With Chronic Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2024;14:101452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Degiorgio D, Colombo C, Seia M, Porcaro L, Costantino L, Zazzeron L, Bordo D, Coviello DA. Molecular characterization and structural implications of 25 new ABCB4 mutations in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 (PFIC3). Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:1230-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zolnerciks JK, Andress EJ, Nicolaou M, Linton KJ. Structure of ABC transporters. Essays Biochem. 2011;50:43-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Guerrero L, Carmona-Rodríguez L, Santos FM, Ciordia S, Stark L, Hierro L, Pérez-Montero P, Vicent D, Corrales FJ. Molecular basis of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis 3. A proteomics study. Biofactors. 2024;50:794-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gordo-Gilart R, Hierro L, Andueza S, Muñoz-Bartolo G, López C, Díaz C, Jara P, Álvarez L. Heterozygous ABCB4 mutations in children with cholestatic liver disease. Liver Int. 2016;36:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hegarty R, Gurra O, Tarawally J, Allouni S, Rahman O, Strautnieks S, Kyrana E, Hadzic N, Thompson RJ, Grammatikopoulos T. Clinical outcomes of ABCB4 heterozygosity in infants and children with cholestatic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:339-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Degiorgio D, Crosignani A, Colombo C, Bordo D, Zuin M, Vassallo E, Syrén ML, Coviello DA, Battezzati PM. ABCB4 mutations in adult patients with cholestatic liver disease: impact and phenotypic expression. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:271-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nayagam JS, Foskett P, Strautnieks S, Agarwal K, Miquel R, Joshi D, Thompson RJ. Clinical phenotype of adult-onset liver disease in patients with variants in ABCB4, ABCB11, and ATP8B1. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2654-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oliveira HM, Pereira C, Santos Silva E, Pinto-Basto J, Pessegueiro Miranda H. Elevation of gamma-glutamyl transferase in adult: Should we think about progressive familiar intrahepatic cholestasis? Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:203-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Denk GU, Bikker H, Lekanne Dit Deprez RH, Terpstra V, van der Loos C, Beuers U, Rust C, Pusl T. ABCB4 deficiency: A family saga of early onset cholelithiasis, sclerosing cholangitis and cirrhosis and a novel mutation in the ABCB4 gene. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:937-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lucena JF, Herrero JI, Quiroga J, Sangro B, Garcia-Foncillas J, Zabalegui N, Sola J, Herraiz M, Medina JF, Prieto J. A multidrug resistance 3 gene mutation causing cholelithiasis, cholestasis of pregnancy, and adulthood biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1037-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fickert P, Fuchsbichler A, Wagner M, Zollner G, Kaser A, Tilg H, Krause R, Lammert F, Langner C, Zatloukal K, Marschall HU, Denk H, Trauner M. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:261-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sticova E, Jirsa M. ABCB4 disease: Many faces of one gene deficiency. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason H, Gudjonsson SA, Zink F, Oddson A, Gylfason A, Besenbacher S, Magnusson G, Halldorsson BV, Hjartarson E, Sigurdsson GT, Stacey SN, Frigge ML, Holm H, Saemundsdottir J, Helgadottir HT, Johannsdottir H, Sigfusson G, Thorgeirsson G, Sverrisson JT, Gretarsdottir S, Walters GB, Rafnar T, Thjodleifsson B, Bjornsson ES, Olafsson S, Thorarinsdottir H, Steingrimsdottir T, Gudmundsdottir TS, Theodors A, Jonasson JG, Sigurdsson A, Bjornsdottir G, Jonsson JJ, Thorarensen O, Ludvigsson P, Gudbjartsson H, Eyjolfsson GI, Sigurdardottir O, Olafsson I, Arnar DO, Magnusson OT, Kong A, Masson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Helgason A, Sulem P, Stefansson K. Large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat Genet. 2015;47:435-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 544] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | de Vries E, Mazzetti M, Takkenberg B, Mostafavi N, Bikker H, Marzioni M, de Veer R, van der Meer A, Doukas M, Verheij J, Beuers U. Carriers of ABCB4 gene variants show a mild clinical course, but impaired quality of life and limited risk for cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2020;40:3042-3050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on genetic cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2024;81:303-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lakli M, Dumont J, Vauthier V, Charton J, Crespi V, Banet M, Riahi Y, Ben Saad A, Mareux E, Lapalus M, Gonzales E, Jacquemin E, Di Meo F, Deprez B, Leroux F, Falguières T. Identification of new correctors for traffic-defective ABCB4 variants by a high-content screening approach. Commun Biol. 2024;7:898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Stättermayer AF, Halilbasic E, Wrba F, Ferenci P, Trauner M. Variants in ABCB4 (MDR3) across the spectrum of cholestatic liver diseases in adults. J Hepatol. 2020;73:651-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Vitale G, Sciveres M, Mandato C, d'Adamo AP, Di Giorgio A. Genotypes and different clinical variants between children and adults in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: a state-of-the-art review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/