Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111902

Revised: August 29, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 198 Days and 19.1 Hours

Artificial intelligence (AI) has made remarkable strides, becoming an essential tool in modern medicine. As AI continues to evolve, it is crucial to redefine its scope, classifications, and subtypes to better align with its clinical applications and po

Core Tip: This article presents a structured overview of artificial intelligence (AI) in gastroenterology and hepatology, integrating fundamental concepts with real-world clinical applications. By aligning AI tools with each stage of the patient journey, we highlight how AI can enhance prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. We also discuss challenges related to trustworthiness, including interpretability, generalisability, and ethics. Through practical examples and original visual frameworks, this article aims to guide clinicians and researchers in understanding, evaluating, and responsibly implementing AI technologies in digestive and liver healthcare.

- Citation: Boutos P, Karakasi KE, Katsanos G, Antoniadis N, Kofinas A, Tsoulfas G. Harnessing artificial intelligence in gastroenterology and hepatology: Current applications and future perspectives. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 111902

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/111902.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111902

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming modern medicine, offering new paradigms in data interpretation, decision support, and personalized care. Gastroenterology and hepatology, fields that inherently rely on multimodal data - from endoscopic imaging and histopathology to complex clinical scores and longitudinal biomarkers - are particularly well positioned to benefit from AI-driven innovations. Over the past decade, a surge in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) applications has demonstrated the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, optimize therapeutic stra

However, the proliferation of AI tools in academic literature has not yet translated into widespread clinical adoption. Significant barriers remain, including technical limitations, ethical concerns, regulatory uncertainty, and lack of integration with existing workflows. Moreover, the diversity of AI methodologies and the often opaque nature of algorithmic decision-making contribute to confusion among clinicians and healthcare stakeholders.

AI refers to a spectrum of computational techniques that emulate human cognitive processes, such as reasoning, pattern recognition, learning, and decision-making. In clinical contexts, AI systems are deployed to interpret complex biomedical data, detect latent structures, and generate actionable insights. AI is typically categorized into “narrow AI”, designed to execute specific clinical tasks - such as polyp classification in endoscopy or fibrosis staging from imaging - and “general AI”, which aspires to approximate human-level intelligence across domains. To date, virtually all medical implementations pertain to narrow AI[1,2].

Translating clinical questions into AI-solvable problems requires formal representation of input data types [e.g., high-resolution endoscopic video, histopathologic slides, longitudinal electronic health record (EHR) sequences] and outcome variables (e.g., disease state, treatment response, or prognosis). Central to the responsible integration of AI are considerations of model interpretability, robustness, and clinical validity. Regulatory frameworks increasingly emphasize model explainability and performance under domain shift - i.e., when applied to populations or settings different from those on which they were trained[3].

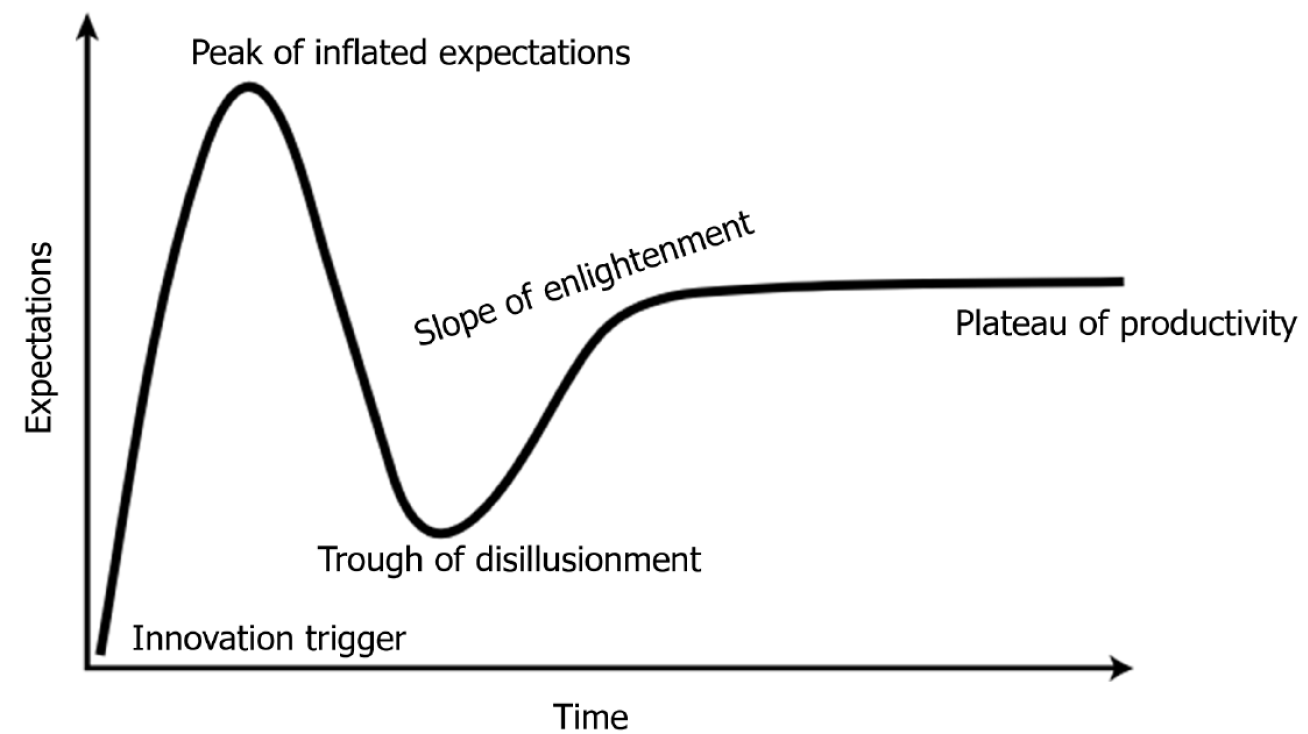

Table 1 summarizes the key features of different AI methodologies, including supervised learning, unsupervised learning, reinforcement learning (RL), and large language models. These approaches vary in terms of data supervision, clinical interpretability, and their maturity for deployment in digestive and liver care. While different AI methodologies differ in structure and application, their translational evolution often follows a similar trajectory. From initial enthusiasm to clinical disappointment, and eventually to mature integration, these innovations typically pass through defined phases of adoption. This pattern is captured by the well-known “hype cycle” model, which helps frame the realistic expectations of AI in medicine over time (Figure 1). Throughout the manuscript, whenever specific AI applications are discussed, the corresponding stage of the hype cycle for each technology will be indicated in parentheses. Readers are therefore encouraged to refer back to Figure 1 in order to contextualize these references and recall the sequential flow of the hype cycle stages.

| AI technique | Input data type | Interpretability | Computational cost | Common clinical applications | Limitations |

| Logistic regression | Structured tabular data | High | Low | Risk scoring (e.g., cirrhosis, NAFLD), binary classification | Assumes linear relationships, limited complexity handling |

| Decision trees/random forests | Structured data, some semi-structured | Moderate to high | Moderate | Prognostic models (e.g., HCC recurrence), treatment stratification | Can overfit, less effective on unstructured data |

| SVM | Structured data, imaging (preprocessed) | Low to moderate | Moderate | Classification tasks (e.g., benign vs malignant lesions) | Less scalable, needs careful kernel tuning |

| CNNs | Imaging data (e.g., endoscopy, CT, MRI) | Low | High | Polyp detection, liver lesion classification, fibrosis staging | Black-box nature, high data requirements |

| RNNs/LSTMs | Time-series data, text sequences | Low | High | Monitoring biomarkers over time, EHR text analysis | Difficult to train, prone to vanishing gradients |

| Transformers/LLMs | Natural language, multimodal inputs | Moderate to low | Very high | Summarization of clinical notes, patient stratification via EHR | Expensive to fine-tune, interpretability challenges |

| Autoencoders/unsupervised learning | Imaging, high-dimensional data | Low | Moderate to high | Anomaly detection, feature extraction | Requires careful architecture design, lacks direct supervision |

| Federated learning | Decentralized structured/unstructured data | Moderate | High | Multi-center model training without data sharing | Complex orchestration, risk of data heterogeneity bias |

This article aims to provide a pragmatic and clinically oriented overview of AI in gastroenterology and hepatology. We follow the patient’s journey through the healthcare system, highlighting AI applications at each stage - from screening and diagnosis to treatment and monitoring. Finally, we address the major challenges in the field, including bias, generalizability, interpretability, and legal-ethical implications, while also offering a forward-looking perspective on responsible AI integration. By anchoring AI within real clinical pathways and challenges, we hope to foster a deeper understanding of its practical utility and limitations, while empowering clinicians to engage critically with emerging technologies.

AI is poised to redefine each phase of the patient journey, offering enhanced accuracy, personalization, and efficiency from early risk prediction to long-term disease management. This section systematically examines how AI can be integrated across this continuum, with a specific focus on validated and emerging applications within gastroenterology and hepatology.

The preclinical phase of disease management is where AI arguably exerts some of its most transformative effects. By leveraging high-dimensional data - ranging from genetic predispositions and environmental exposures to lifestyle metrics and longitudinal clinical records - AI models can identify at-risk populations with remarkable granularity. It is worth noting that in these screening models the sensitivity and specificity metrics are of great importance.

In the prevention and early detection setting, ML provides the foundation (plateau of productivity). ML, a core subfield of AI, encompasses statistical learning techniques that infer predictive functions from data. Supervised learning remains the most widely adopted paradigm in clinical research, relying on labeled datasets to train discriminative or generative models[4,5]. For instance, annotated colonoscopy frames with polyp labels enable the development of real-time lesion detection tools (slope of enlightenment), while fibrosis scores based on liver biopsy guide ML models for non-invasive fibrosis prediction (peak of inflated expectations).

Unsupervised learning (trough of disillusionment) is instrumental in uncovering latent structures within unlabeled datasets. In hepatology, clustering algorithms have delineated phenotypic subgroups within non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, suggesting differential trajectories of metabolic dysfunction and fibrosis risk. Semi-supervised learning (innovation trigger) leverages small labeled subsets alongside large unlabeled data volumes, an especially advantageous strategy in resource-limited environments. RL, though still in its early clinical applications, is a paradigm in which an agent learns to make sequential decisions through interactions with an environment, with the objective of maximizing a cumulative reward signal. This approach shows considerable promise for dynamic treatment optimization[6,7].

ML pipelines require meticulous attention to preprocessing, feature engineering, algorithm selection, model tuning, and validation. High-stakes medical applications necessitate performance calibration and uncertainty quantification, increasingly evaluated using reliability diagrams and Bayesian ensembling (trough of disillusionment)[8].

In gastroenterology, colorectal cancer screening has become a flagship area for AI deployment. Computer-aided de

In hepatology, ML frameworks have shown immense promise in stratifying risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly among patients with cirrhosis or viral hepatitis. Ioannou et al[12] employed recurrent neural networks to analyze EHR data from over 48000 patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis, outperforming conventional regression-based models in forecasting HCC incidence. Likewise, the “SMART” model - a random survival forest incorporating seven longitudinal variables - (slope of enlightenment) has been validated as a robust prognostic tool in patients who have achieved sustained virologic response post-HCV treatment[13].

The diagnostic process in gastroenterology and hepatology is increasingly augmented by AI algorithms that in many cases outperform traditional image analysis and interpretation methods. In gastrointestinal endoscopy, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (plateau of productivity) have achieved near-pathologist-level performance.

Here, DL becomes central. DL, a specialized class of ML, is predicated on artificial neural networks with multiple processing layers, enabling the automatic extraction of hierarchical feature representations. CNNs are the predominant architecture for visual data and are widely used in endoscopic image analysis - for example, distinguishing neoplastic from benign colorectal lesions[9]. Similarly, CNNs applied to radiologic imaging support automated liver lesion classification and fibrosis quantification[14].

Temporal data modalities benefit from sequence modeling approaches such as recurrent neural networks, long short-term memory (trough of disillusionment), and, more recently, transformer models that utilize attention mechanisms. Additionally, autoencoders and generative adversarial networks facilitate dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection, and generation of synthetic clinical data.

DL models are computationally intensive and often data-hungry. Strategies such as transfer learning, multi-task learning, and data augmentation are employed to circumvent data limitations. Interpretability remains a critical bottleneck, prompting the development of explainability frameworks (e.g., Shapley Additive Explanations, Integrated Gradients).

Urban et al[4] demonstrated that a CNN could classify colorectal polyps in real time with 96% accuracy (area under the curve = 0.991), while Byrne et al[15] successfully trained a model to distinguish between diminutive adenomas and hyperplastic polyps with performance comparable to histologic assessment. Meta-analytic data suggest that AI systems now surpass human endoscopists in sensitivity (88% vs 80%) without compromising specificity[16].

Beyond colonoscopy, AI has revolutionized capsule endoscopy interpretation (Slope of Enlightment). Architectures such as focus U-Net (peak of inflated expectations) have achieved Dice similarity coefficients exceeding 0.90, enabling high-throughput identification of bleeding, ulcers, and inflammatory lesions in Crohn’s disease[17]. This not only reduces inter-observer variability but also drastically shortens reading times.

In hepatology, AI facilitates non-invasive diagnostics through enhanced image and signal interpretation. DL models trained on elastography and ultrasound datasets have refined fibrosis staging, offering more precise classification of bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis[18]. Furthermore, natural language processing (NLP) (peak of inflated expectations) has proven effective in structuring diagnostic insights from free-text radiology and pathology reports, fostering multidisciplinary coordination and reducing diagnostic latency[19].

Equally critical in the diagnostic domain is computer vision (CV) (slope of enlightenment), which enables automated interpretation of visual data. CV models classify, segment, and detect structures across diverse imaging modalities. In gastroenterology, CV underpins real-time polyp detection systems, quantifies inflammatory burden, and differentiates subtle dysplastic changes. In hepatology, CV supports lesion classification across ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, while in pathology it powers whole-slide analysis, grading inflammation, and detecting dysplastic foci with precision that often surpasses inter-observer variability. Domain adaptation techniques are applied to ensure CV algorithms generalize across scanners, staining protocols, and populations.

Once a diagnosis is established, AI contributes to longitudinal disease modeling, surpassing static clinical scores in predictive granularity. At this stage, more advanced paradigms like federated (innovation trigger), transfer (innovation trigger), and multi-modal learning (peak of inflated expectations) are most relevant. Federated learning enables decentralized model training across hospitals while preserving privacy. Transfer learning adapts pretrained models to clinical data. Multi-modal learning integrates diverse data streams, uncovering complex phenotypes in conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or HCC. Ethical AI development mandates rigorous attention to bias mitigation, fairness, and transparency. Algorithms must be audited for differential performance across groups, and pipelines should include bias detection steps.

In the realm of IBD, ML models have been constructed to forecast steroid dependence, hospitalizations, and the necessity for surgical intervention. These models synthesize diverse data streams - including serological markers, imaging data, endoscopic severity, and transcriptomics - enabling predictions that outperform standard tools such as the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index or Partial Mayo Score[20]. For instance, a gradient boosting model trained on multi-modal inputs has demonstrated superior predictive capacity for 12-month colectomy risk[21].

In hepatology, AI-derived risk models are actively shaping clinical algorithms for decompensation, variceal hemorrhage, and HCC (slope of enlightenment). Models trained on large national registries, including the Veterans Affairs dataset, have exhibited the capacity to predict acute-on-chronic liver failure several weeks prior to its onset[22]. AI is also being employed to recalibrate organ allocation frameworks: By incorporating frailty indices, radiomics, and dynamic laboratory trends into model for end-stage liver disease-based models, AI augments the fairness and utility of transplantation prioritization[23].

AI is rapidly evolving from a diagnostic adjunct to a decision-support partner capable of informing therapeutic strategy and personalization. In gastroenterology, RL models (innovation trigger) are being developed to optimize biologic sequencing in IBD, based on probabilistic modeling of long-term remission and adverse events[24]. Additionally, pharmacogenomic AI tools are under development to individualize treatment in Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastrointestinal oncology, integrating single nucleotide polymorphism data and microbial resistance profiles[25]. In hepatology, predictive modeling is being employed to tailor antiviral regimens in hepatitis B and C by analyzing tr

Chronic disease monitoring benefits from AI’s capacity for continuous data assimilation and anomaly detection. In IBD, AI-enabled mobile applications aggregate real-time patient-reported outcomes, biomarker data, and wearable sensor outputs to detect subclinical flares or therapeutic failure. These platforms increasingly leverage federated learning approaches, allowing model improvement without centralizing sensitive patient data[29]. For patients in endoscopic surveillance programs (e.g., Barrett’s esophagus or post-polypectomy cohorts) (plateau of productivity), AI systems are utilized to standardize follow-up schedules and automate red flag identification during endoscopic review[30]. In hepatology, real-time monitoring of patients with cirrhosis is being augmented through AI algorithms analyzing actigraphy, alcohol intake patterns, and sleep disruption, all of which correlate with hepatic encephalopathy risk[31]. Predictive models applied to lab data trajectories have also demonstrated early warning capabilities for inpatient de

AI-driven tools are also revolutionizing patient engagement, health literacy, and remote care delivery. In this sphere of engagement and remote care, NLP and conversational AI play a central role. In gastroenterology, conversational AI chatbots provide symptom triage, nutritional advice, and procedural guidance, notably improving bowel preparation adherence[33]. NLP-based systems are increasingly used to generate simplified summaries of procedural and imaging reports, enhancing patient understanding and shared decision-making[34].

In hepatology, intelligent virtual assistants support (peak of inflated expectations) patients with cirrhosis through medication reminders, lifestyle interventions, and psychosocial support. These systems dynamically adapt to patient inputs and behaviors, increasing adherence and engagement[35]. Telemedicine platforms with embedded AI (slope of enlightenment) triage functions have proven effective in monitoring high-risk patients, enabling clinicians to detect and intervene upon early signs of decompensation[36].

Beyond simple chatbots, NLP techniques are evolving toward more advanced patient-facing applications (innovation trigger). Transformer-based language models (e.g., BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, GatorTron) can generate personalized, easy-to-understand summaries of complex medical reports, enhancing health literacy and shared decision-making. NLP also supports real-time translation of medical instructions, enabling non-native speakers or low-literacy patients to better follow therapeutic regimens. Furthermore, sentiment analysis algorithms are beginning to be integrated into patient communication platforms, helping clinicians detect early signs of anxiety, depression, or disengagement in chronic disease management.

Another promising domain is automated documentation: Conversational AI integrated with telemedicine platforms can transcribe, structure, and code virtual consultations in real time, reducing clinician workload while simultaneously generating patient-friendly outputs. These systems are being trialed in gastroenterology follow-up clinics and liver transplant programs, where efficiency and patient comprehension are equally critical.

A structured overview of representative AI applications across the digestive and hepatic patient journey is presented in Table 2. It highlights how AI tools can contribute to each clinical stage, from early risk prediction to post-treatment surveillance. Collectively, these applications illustrate a paradigm in which AI serves not as a standalone tool, but as an integrated framework augmenting clinical reasoning across all phases of the patient journey. As the evidence base matures, robust validation, seamless workflow integration, and ethical governance will be paramount to realizing AI’s full transformative potential - topics explored in the subsequent section.

| Stage of patient journey | Clinical context | Representative AI applications | Benefits/added value | Hype cycle stage | Ref. |

| Risk stratification and screening | Asymptomatic or high-risk individuals | Predictive modeling for NAFLD, HCC, CRC risk | Early identification of at-risk patients, targeted screening programs | Slope of enlightenment | [1] |

| Polygenic/biomarker-based risk stratification using EHR and genomics | |||||

| Diagnosis | Symptomatic presentation or incidental findings | AI-assisted polyp detection during colonoscopy (real-time CADe) | Increased diagnostic accuracy, real-time decision support, reduced miss rates of small/flat lesions | Plateau of productivity (for CADe in CRC); peak of inflated expectations (for capsule endoscopy CNNs) | [4,12,15] |

| Image-based classification of liver lesions (CNNs) | |||||

| Capsule endoscopy with U-Net architectures | |||||

| Staging and prognostication | Confirmed disease (IBD, cirrhosis, cancer) | Fibrosis staging via elastography DL | Improved risk assessment, personalized follow-up plans | Slope of enlightenment | [4,15] |

| AI HCC recurrence risk prediction (random survival forests) | |||||

| Prognostic models (ML, MELD + AI) | |||||

| Treatment planning | Therapeutic decision-making | AI-augmented MDT support for IBD biologics | Data-informed, individualized therapeutic pathways | Innovation trigger → early peak | Radiomics-based TACE prediction, AUC 0.78-0.85[36] |

| RL models for drug sequencing | |||||

| Radiomics + ML for TACE suitability in HCC | |||||

| Therapy monitoring | During pharmacologic, endoscopic, or surgical therapy | AI-based monitoring of treatment response (e.g., colectomy trends) | Dynamic tracking, early alerts, adaptive therapy modulation | Peak of inflated expectations | Colectomy prediction, AUROC 0.80-0.83[36]; NLP AE detection, recall 074-0.82[41,43] |

| NLP for adverse event detection | |||||

| Follow-up and surveillance | Post-therapy or remission phase | Predictive models for relapse in IBD | Enhanced vigilance, resource optimization, reduced recurrence risk | Slope of enlightenment | IBD relapse models, AUROC 0.79-0.82[20,22] |

| Surveillance of HCC post-resection using ML | |||||

| Patient engagement and education | Across all stages | AI chatbots for symptom triage | Empowered patients, improved adherence, scalable support | Peak of inflated expectations (for chatbots); innovation trigger (for advanced NLP coaching) | [34] |

| Personalized education via NLP-based tools | |||||

| Digital coaching for diet/lifestyle adherence |

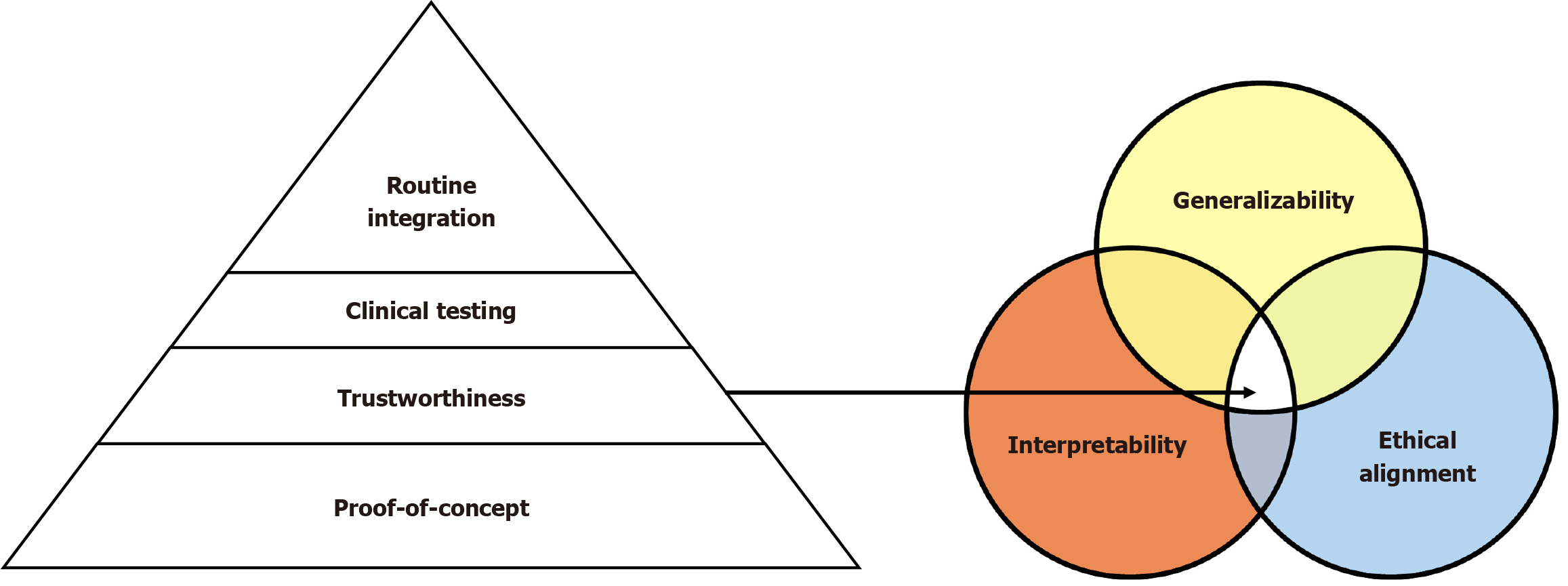

Despite the transformative potential of AI in the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology, the pathway to seamless integration into everyday clinical workflows is fraught with multifaceted challenges. These limitations extend across technical, ethical, regulatory, operational, and sociocultural domains, necessitating a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and iterative approach to resolution. A conceptual framework often used to assess the maturity and translational trajectory of AI tools in medicine is the AI readiness pyramid, which delineates a progression from proof-of-concept development, through trustworthiness and clinical validation, to full-scale integration into routine practice (Figure 2). This section provides a rigorous scholarly analysis of the most pressing barriers confronting AI deployment in digestive and hepatic medicine, alongside emerging paradigms, methodological innovations, and strategic frameworks that aim to facilitate responsible adoption and clinical translation.

The cornerstone of any AI system is the availability of high-quality, representative, and well-annotated data. In gastroenterology and hepatology, the data ecosystem is highly heterogeneous, encompassing diverse modalities such as digital endoscopy, high-resolution cross-sectional imaging (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography), his

Generalization beyond the training domain remains a critical vulnerability. Models trained on data from single institutions or narrow patient demographics frequently demonstrate degraded performance when externally validated across different healthcare systems, geographic regions, or disease subtypes[1]. For instance, CNNs trained to detect cirrhosis using ultrasound imaging from North American datasets may exhibit biased outputs or significant performance attenuation in African or Southeast Asian populations due to differences in etiological prevalence, imaging acquisition protocols, or hepatic phenotypic expression.

Embedded biases - whether racial, gender-based, socioeconomic, or systemic - can be encoded in training datasets, propagating inequities in algorithmic outputs. Addressing these challenges demands deliberate inclusion of diverse datasets, rigorous subgroup performance auditing, and adoption of fairness-aware algorithms. Additionally, advanced methodological approaches such as federated learning, domain adaptation, and transfer learning offer viable strategies to mitigate overfitting, improve domain generalization, and uphold data privacy and regulatory compliance frameworks such as General Data Protection Regulation and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act[15].

One of the most contentious and persistent obstacles in the adoption of clinical AI is the interpretability of complex models, particularly those built upon DL architectures. These systems, often comprising millions or even billions of parameters, generate highly accurate predictions but do so through internal mechanisms that remain largely inscrutable to human observers. As a result, they are frequently described as “black boxes”, since the decision-making pathway cannot be easily traced or rationalized. This lack of transparency poses significant challenges in clinical practice, where trust, accountability, and justification of decisions are indispensable. For instance, when an AI model recommends a diagnostic pathway or flags a high-risk patient, clinicians must be able to explain the reasoning to patients, colleagues, and regulatory bodies. Without such interpretability, even the most statistically robust models risk rejection or underutilization. Moreover, the opacity of DL systems exacerbates ethical concerns, as errors or biases embedded in training data can propagate unchecked, making it difficult to assign responsibility when adverse outcomes occur. Consequently, improving interpretability is not merely a technical ambition but a clinical and ethical necessity. Ongoing research into explainable AI seeks to address this barrier, through methods such as attention mapping, feature attribution, and post-hoc interpretive models, yet these approaches remain imperfect and often oversimplify the underlying complexity. The tension between predictive power and transparency thus constitutes a central dilemma for the future of clinical AI adoption[39]. In critical clinical contexts - such as liver transplantation eligibility or oncologic staging - clinicians demand not only high performance but also an intelligible rationale that can be reconciled with existing clinical heuristics and medical reasoning.

To address this concern, interpretability-enhancing techniques have been developed. Model-agnostic approaches such as Shapley Additive Explanations and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations, as well as model-specific methods like Grad-Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping and Integrated Gradients, seek to visualize decision saliency, highlight influential input features, and simulate counterfactual scenarios[40]. While these tools offer valuable insights, their validity, stability, and reproducibility in high-stakes clinical settings remain areas of active investigation.

Building clinical trust in AI extends beyond technical interpretability. It involves participatory co-design frameworks wherein clinicians contribute to iterative model development and refinement. Embedding interpretability from the inception of model construction - rather than treating it as an ex post facto explanation layer - enhances credibility, usability, and safety[40]. Furthermore, real-world monitoring, feedback loops, and continuous learning pipelines are essential to maintain model relevance and clinician trust over time.

The regulatory landscape for AI in medicine is in flux, characterized by a lack of harmonization, evolving definitions, and adaptive requirements. Agencies such as the United States Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and Health Canada have initiated frameworks for software as a medical device, encompassing premarket validation, real-world evidence generation, and lifecycle surveillance[41]. However, existing regulatory paradigms are largely designed for static software systems, whereas contemporary AI applications - particularly those involving continual learning or self-updating algorithms - challenge these conventional constructs.

To bridge this regulatory mismatch, forward-looking proposals such as algorithmic pre-certification programs, adaptive approval mechanisms, and algorithmic change control protocols are gaining traction. These frameworks advocate for iterative oversight, risk-tiered validation, and ongoing post-deployment evaluation.

Ethically, the integration of AI introduces profound questions around autonomy, data sovereignty, consent gra

From a legal perspective, issues of liability in AI-mediated decision-making remain underdefined. Jurisdictional am

The evolution of AI in medicine has been punctuated by notable failures, many of which serve as critical learning opportunities. Early efforts to deploy real-time AI-based polyp detection systems in colonoscopy often failed during clinical translation due to insufficient generalizability, poor handling of motion artifacts, operator-induced variability, and lack of integration into endoscopic workflow[21]. These shortcomings underscored the limitations of training on static, curated datasets without accounting for real-world complexity.

In hepatology, predictive models for HCC recurrence frequently exhibit limited applicability across diverse patient populations, especially when trained on homogeneous cohorts or single-etiology data (e.g., HCV-dominant datasets)[14]. Methodological flaws - including data leakage, label imbalance, overfitting, and inadequate external validation - continue to undermine many published models, diminishing clinical confidence.

Methodological rigor is paramount. Adherence to standardized reporting guidelines such as TRIPOD-AI for model development and DECIDE-AI for early clinical evaluation is essential. Prospective multicenter trials, external validation in real-world settings, and robust post-deployment monitoring are prerequisites for responsible implementation. Furthermore, aligning AI tools with existing clinical workflows and ensuring seamless integration into EHR and Picture Archiving and Communication Systems are indispensable for sustainable impact.

The future trajectory of AI in gastroenterology and hepatology should prioritize augmentation rather than automation of clinical judgment. Next-generation systems are envisioned to integrate multi-modal data streams - including genomics, proteomics, digital histopathology, imaging biomarkers, and patient-reported outcomes - into context-aware decision support systems that enable personalized, dynamic, and anticipatory care[43].

Human-in-the-loop, or human-supervised AI, refers to AI architectures in which human clinical judgment remains an active and integral component of the decision-making process. In this paradigm, clinicians do not merely serve as passive end-validators but rather as dynamic supervisors who iteratively provide feedback to guide and refine the system, thereby enhancing accuracy and mitigating systemic errors. Such hybrid frameworks aim to merge the computational scalability, speed, and capacity for large-scale data processing inherent to AI with the ethical reasoning, clinical expertise, and contextual sensitivity unique to human practitioners. This synergistic integration aspires not only to improve safety and accountability but also to ensure that algorithmic outputs are meaningfully aligned with the nuanced realities of medical practice.

Foundation models trained on large-scale, cross-specialty, and multi-institutional datasets promise to revolutionize the AI landscape. Fine-tuned versions of such models could serve as universal backbones, supporting a range of clinical tasks from colorectal cancer screening during colonoscopy to advanced fibrosis detection in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients using non-invasive imaging. Coupled with remote monitoring platforms and wearable biosensors, AI systems could enable real-time disease tracking and early intervention.

Medical education must evolve to equip future practitioners with core competencies in AI literacy, algorithmic validation, and digital ethics. A useful conceptual framework for situating these stages of development is the “AI readiness pyramid” (Figure 2), which outlines the progressive trajectory from proof-of-concept validation, through the establishment of trustworthiness and clinical testing, to the eventual routine integration of AI into clinical workflows. Beyond general awareness, curricula should emphasize specific skills such as interpreting model validation metrics (e.g., area under the curve, precision-recall, calibration curves), understanding principles of data privacy and governance, and developing the ability to critically appraise AI-related studies for biases, generalizability, and clinical relevance. Interdisciplinary training programs - spanning clinical medicine, computer science, biostatistics, health informatics, and law - are therefore essential to cultivate the next generation of clinician-data scientists. Finally, the principle of equity must remain foundational. This requires systemic efforts to identify and mitigate bias, involve underserved communities in AI development, and validate models across diverse demographic and geographic cohorts. Ultimately, the promise of AI in digestive and hepatic medicine will be realized not solely through algorithmic sophistication but through principled stewardship, inclusivity, and a relentless commitment to patient-centered innovation.

AI is poised to transform gastroenterology and hepatology by enhancing every phase of the patient journey - from early risk prediction and cancer screening to advanced fibrosis staging, treatment personalization, and long-term monitoring of chronic liver and intestinal diseases. In gastroenterology, validated AI tools such as computer-aided detection systems in colonoscopy have already demonstrated substantial improvements in adenoma detection, while in hepatology, ML models are redefining risk stratification for HCC and guiding non-invasive fibrosis assessment. These advances illustrate the discipline-specific potential of AI to improve diagnostic precision, optimize therapeutic strategies, and standardize follow-up care.

Despite this momentum, widespread implementation remains contingent upon overcoming key challenges: Ensuring the quality and representativeness of multimodal data, improving interpretability of complex models, and embedding AI systems seamlessly into endoscopic suites, hepatology clinics, and transplant programs. Future progress will require robust validation in multicenter trials, alignment with regulatory frameworks, and the development of interdisciplinary training to equip clinicians with AI literacy and evaluative skills. Ultimately, the promise of AI in gastroenterology and hepatology is not to supplant clinical expertise but to augment it - providing clinicians with powerful, data-driven tools that enhance decision-making, improve patient outcomes, and drive a new era of precision digestive and hepatic me

| 1. | Topol EJ. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again. New York: Basic Books, 2019. |

| 2. | Jha S, Topol EJ. Adapting to Artificial Intelligence: Radiologists and Pathologists as Information Specialists. JAMA. 2016;316:2353-2354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wiens J, Saria S, Sendak M, Ghassemi M, Liu VX, Doshi-Velez F, Jung K, Heller K, Kale D, Saeed M, Ossorio PN, Thadaney-Israni S, Goldenberg A. Do no harm: a roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care. Nat Med. 2019;25:1337-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 65.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Urban G, Tripathi P, Alkayali T, Mittal M, Jalali F, Karnes W, Baldi P. Deep Learning Localizes and Identifies Polyps in Real Time With 96% Accuracy in Screening Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1069-1078.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Dong LQ, Peng LH, Ma LJ, Liu DB, Zhang S, Luo SZ, Rao JH, Zhu HW, Yang SX, Xi SJ, Chen M, Xie FF, Li FQ, Li WH, Ye C, Lin LY, Wang YJ, Wang XY, Gao DM, Zhou H, Yang HM, Wang J, Zhu SD, Wang XD, Cao Y, Zhou J, Fan J, Wu K, Gao Q. Heterogeneous immunogenomic features and distinct escape mechanisms in multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:896-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Frommeyer TC, Gilbert MM, Fursmidt RM, Park Y, Khouzam JP, Brittain GV, Frommeyer DP, Bett ES, Bihl TJ. Reinforcement Learning and Its Clinical Applications Within Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Precision Medicine and Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Healthcare (Basel). 2025;13:1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu KH, Beam AL, Kohane IS. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:719-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1198] [Article Influence: 149.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kompa B, Snoek J, Beam AL. Second opinion needed: communicating uncertainty in medical machine learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Repici A, Badalamenti M, Maselli R, Correale L, Radaelli F, Rondonotti E, Ferrara E, Spadaccini M, Alkandari A, Fugazza A, Anderloni A, Galtieri PA, Pellegatta G, Carrara S, Di Leo M, Craviotto V, Lamonaca L, Lorenzetti R, Andrealli A, Antonelli G, Wallace M, Sharma P, Rosch T, Hassan C. Efficacy of Real-Time Computer-Aided Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:512-520.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 74.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Kataoka H, Takatani T, Sugie K. Two-Channel Portable Biopotential Recording System Can Detect REM Sleep Behavioral Disorder: Validation Study with a Comparison of Polysomnography. Parkinsons Dis. 2022;2022:1888682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sundararajan M, Taly A, Yan Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In: Precup D, Teh YW. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6-11; Sydney NSW Australia. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2017: 3319-3328. |

| 12. | Ioannou GN, Tang W, Beste LA, Tincopa MA, Su GL, Van T, Tapper EB, Singal AG, Zhu J, Waljee AK. Assessment of a Deep Learning Model to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Hepatitis C Cirrhosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2015626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rohr-Udilova N, Tsuchiya K, Timelthaler G, Salzmann M, Meischl T, Wöran K, Stift J, Herac M, Schulte-Hermann R, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Sieghart W, Eferl R, Jensen-Jarolim E, Trauner M, Pinter M. Morphometric Analysis of Mast Cells in Tumor Predicts Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Liver Transplantation. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:1939-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anteby R, Klang E, Horesh N, Nachmany I, Shimon O, Barash Y, Kopylov U, Soffer S. Deep learning for noninvasive liver fibrosis classification: A systematic review. Liver Int. 2021;41:2269-2278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Byrne MF, Chapados N, Soudan F, Oertel C, Linares Pérez M, Kelly R, Iqbal N, Chandelier F, Rex DK. Real-time differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic diminutive colorectal polyps during analysis of unaltered videos of standard colonoscopy using a deep learning model. Gut. 2019;68:94-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang P, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR, Bharadwaj S, Becq A, Xiao X, Liu P, Li L, Song Y, Zhang D, Li Y, Xu G, Tu M, Liu X. Real-time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: a prospective randomised controlled study. Gut. 2019;68:1813-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Walter B, Klare P, Strehle K, Aschenbeck J, Ludwig L, Dikopoulos N, Mayr M, Neu B, Hann A, Mayer B, Meining A, von Delius S. Improving the quality and acceptance of colonoscopy preparation by reinforced patient education with short message service: results from a randomized, multicenter study (PERICLES-II). Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:506-513.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gwag T, Ma E, Zhou C, Wang S. Anti-CD47 antibody treatment attenuates liver inflammation and fibrosis in experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis models. Liver Int. 2022;42:829-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brestel EP, Thrush LB. The treatment of glucocorticosteroid-dependent chronic urticaria with stanozolol. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;82:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Corrigendum to Postoperative Outcomes in Vedolizumab-Treated Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Operations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCarthy C, Clyne B, Boland F, Moriarty F, Flood M, Wallace E, Smith SM; SPPiRE Study team. GP-delivered medication review of polypharmacy, deprescribing, and patient priorities in older people with multimorbidity in Irish primary care (SPPiRE Study): A cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022;19:e1003862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Shamrani HAA, Khalil H, Khan MS. Awareness and Utilization of ROME Criteria for Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome among Primary Care Physicians in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Mater Sociomed. 2020;32:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gustot T, Stadlbauer V, Laleman W, Alessandria C, Thursz M. Transition to decompensation and acute-on-chronic liver failure: Role of predisposing factors and precipitating events. J Hepatol. 2021;75 Suppl 1:S36-S48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lin S, Araujo C, Hall A, Kumar R, Phillips A, Hassan M, Engelmann C, Quaglia A, Jalan R. Prognostic Role of Liver Biopsy in Patients With Severe Indeterminate Acute Hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1130-1141.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kye BH, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Lee YS, Lee IK, Kang WK, Cho HM, Ahn CH, Oh ST. The optimal time interval between the placement of self-expandable metallic stent and elective surgery in patients with obstructive colon cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Park H, Lo-Ciganic WH, Huang J, Wu Y, Henry L, Peter J, Sulkowski M, Nelson DR. Machine learning algorithms for predicting direct-acting antiviral treatment failure in chronic hepatitis C: An HCV-TARGET analysis. Hepatology. 2022;76:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang L, Jiang Y, Jin Z, Jiang W, Zhang B, Wang C, Wu L, Chen L, Chen Q, Liu S, You J, Mo X, Liu J, Xiong Z, Huang T, Yang L, Wan X, Wen G, Han XG, Fan W, Zhang S. Real-time automatic prediction of treatment response to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using deep learning based on digital subtraction angiography videos. Cancer Imaging. 2022;22:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Khalil NY, Bakheit AH, Alkahtani HM, Al-Muhanna T. Vinpocetine (A comprehensive profile). Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2022;47:1-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, Milletarì F, Roth HR, Albarqouni S, Bakas S, Galtier MN, Landman BA, Maier-Hein K, Ourselin S, Sheller M, Summers RM, Trask A, Xu D, Baust M, Cardoso MJ. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 857] [Article Influence: 142.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Groof AJ, Struyvenberg MR, van der Putten J, van der Sommen F, Fockens KN, Curvers WL, Zinger S, Pouw RE, Coron E, Baldaque-Silva F, Pech O, Weusten B, Meining A, Neuhaus H, Bisschops R, Dent J, Schoon EJ, de With PH, Bergman JJ. Deep-Learning System Detects Neoplasia in Patients With Barrett's Esophagus With Higher Accuracy Than Endoscopists in a Multistep Training and Validation Study With Benchmarking. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:915-929.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Zhai Y, Hai D, Zeng L, Lin C, Tan X, Mo Z, Tao Q, Li W, Xu X, Zhao Q, Shuai J, Pan J. Artificial intelligence-based evaluation of prognosis in cirrhosis. J Transl Med. 2024;22:933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Müller SE, Casper M, Ripoll C, Zipprich A, Horn P, Krawczyk M, Lammert F, Reichert MC. Machine Learning Models predicting Decompensation in Cirrhosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2025;34:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Pellegrino R, Federico A, Gravina AG. Conversational LLM Chatbot ChatGPT-4 for Colonoscopy Boston Bowel Preparation Scoring: An Artificial Intelligence-to-Head Concordance Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14:2537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ethan Tan K, Sesagiri Raamkumar A, Wee HL. Impact of COVID-19 on the outreach strategy of cancer social service agencies in Singapore: A pre-post analysis with Facebook data. J Biomed Inform. 2021;118:103798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fang S, Yang Y, Tao J, Yin Z, Liu Y, Duan Z, Liu W, Wang S. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Fibrosarcoma Xenograft Models: Whole-Tumor Histogram Analysis of DWI and IVIM. Acad Radiol. 2023;30:2299-2308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2121] [Cited by in RCA: 3445] [Article Influence: 430.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 37. | Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B, Kuleshov V, DePristo M, Chou K, Cui C, Corrado G, Thrun S, Dean J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2019;25:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1123] [Cited by in RCA: 1799] [Article Influence: 257.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hashimoto DA, Rosman G, Rus D, Meireles OR. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Promises and Perils. Ann Surg. 2018;268:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 701] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rudin C. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2479] [Cited by in RCA: 2099] [Article Influence: 299.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jin W, Li X, Fatehi M, Hamarneh G. Generating post-hoc explanation from deep neural networks for multi-modal medical image analysis tasks. MethodsX. 2023;10:102009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Holzinger A, Langs G, Denk H, Zatloukal K, Müller H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov. 2019;9:e1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 70.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | United States Food and Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning(AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan. Jan 2021. [cited 12 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/145022/download. |

| 43. | Vayena E, Blasimme A, Cohen IG. Machine learning in medicine: Addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/