Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.112364

Revised: August 28, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 125 Days and 21.6 Hours

The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and antiangiogenic drugs has shown promising efficacy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). How

To identify predictive biomarkers in HCC patients treated with sintilimab (pro

In this single-center study in China, patients with unresectable HCC received sintilimab every 21 days and daily oral lenvatinib. Treatment response was assessed by modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors. Tumor biopsies underwent RNA sequencing, immune microenvironment profiling, and whole-exome sequencing. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and immune cell subsets between response groups were identified, followed by survival analyses. All potential predictors of PFS, together with clinical variables, were included in Cox regression to identify independent prognostic factors.

Between August 2019 and November 2021, 33 patients with hepatitis-B-virus-related HCC were enrolled; by January 2024, 13 had undergone potentially curative surgery or ablation. RNA sequencing identified 94 DEGs between responders (n = 22) and non-responders (n = 11) using Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test (all

Sintilimab plus lenvatinib showed heterogeneous efficacy in HCC. High LINC01554 expression, elevated CD4+ Tcm cells, and solitary tumors may serve as predictive biomarkers for prolonged disease control.

Core Tip: The efficacy of sintilimab plus lenvatinib in hepatocellular carcinoma is highly variable. This study integrated RNA sequencing, immune profiling, and whole-exome sequencing to identify predictive biomarkers. High long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 01554 expression, elevated CD4+ central memory T cells, and solitary tumors were independent predictors of prolonged progression-free survival. These findings highlight the potential of molecular and immune markers to guide individualized treatment strategies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Wang LJ, Cui Y, Huang LF, Zhang JQ, Zhao TT, Wang HW, Liu M, Jin KM, Wang K, Xing BC. Molecular biomarkers of sintilimab plus lenvatinib in hepatitis-B-virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 112364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/112364.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.112364

Primary liver cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide[1]. In 2018, it globally ranked sixth in terms of the incidence of malignant tumors and fourth in terms of cancer-related deaths[2,3]. In primary liver cancer, 75%-85% of cases are diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[2]. In contrast to Europe and the United States, the main causative factor for liver cancer in China is chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and the majority of cases have al

Sintilimab is an anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody that has exhibited a high anti-tumor activity in previous studies, especially in Hodgkin’s lymphoma[8,9]. Lenvatinib is an orally administered multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that has been approved for the first-line treatment of unresectable HCC[10]. However, our study found that there are variations in tumor regression and progression-free survival (PFS) of different patients after receiving this combination therapy, suggesting that it may be inappropriate for all patients[7]. Given the likelihood of adverse events and the potential inefficacy of the combined treatment strategy, accurately predicting therapeutic effectiveness in advance is of utmost importance.

Previous studies have identified several gene mutations that could be associated with the efficacy of targeted therapy for HCC, including vascular endothelial growth factor A, RAS, MET, tumor protein p53, and fibroblast growth factor-19[11]. Additionally, potential molecular pathways include the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin, homologous recombination deficiency, and fibroblast growth factor receptor pathways[12]. The indicators potentially associated with the efficacy of immunotherapy for HCC include programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability, mismatch repair, serine threonine kinase 11/Liver kinase B1, polymerase-epsilon, Wnt/catenin beta 1 mutations, and others[13]. However, these indicators have not been widely applied in HCC. Furthermore, molecular biomarkers for combination of immunotherapy with targeted therapy have not yet been identified. Recently, advances in whole-exome sequencing (WES)[14] and transcriptome sequencing technologies[15] have made it possible to explore molecular characteristics of tumors in advance, assisting clinicians in making clinical decisions.

The present study aimed to analyze the gene expression profiles of HCC tissues within the study cohort. It was also attempted to assess potential molecular biomarkers that could be associated with the efficacy of the combination therapy involving sintilimab and lenvatinib. Additionally, the prognostic significance of these biomarkers was investigated, providing valuable predictive information regarding treatment outcomes.

This retrospective cohort study primarily evaluated the role of tumor tissue biomarkers in predicting treatment efficacy in HCC patients who were ineligible for surgical resection at diagnosis. Tumor tissues were obtained from patients enrolled in a prospective, single-arm, single-center, nonrandomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: No. NCT04042805). The trial included 36 patients with intermediate or locally advanced HCC not eligible for resection and treated with sintilimab plus lenvatinib. Among them, 33 patients with HBV-associated HCC and available tumor tissue for sequencing were proce

The key inclusion and exclusion criteria for the prospective clinical trial were as follows. Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years, had histologically confirmed HCC [Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B or C] without extrahepatic spread, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0-1, a Child-Pugh score ≤ 7, and adequate organ function. Exclusion criteria included fibrolamellar, sarcomatoid, or cholangiocarcinoma subtypes; history of liver transplantation; invasion of both the main portal vein and superior mesenteric vein; prior systemic or locoregional therapy; or prior exposure to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or lenvatinib. More detailed criteria were described in our published study[7]. After enrollment, all participants received a combination of sintilimab and lenvatinib (sintilimab: 200 mg intravenously every 21 days; lenvatinib: 12 mg orally for body weight ≥ 60 kg or 8 mg for < 60 kg). Treatment continued until surgery, disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal, or death. Patients who converted to surgery underwent hepatectomy (e.g., wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy, or hemihepatectomy, as appropriate). Per protocol, the total duration of combination therapy before and after surgery was limited to eight cycles; if more than eight cycles were given preoperatively, no adjuvant therapy was administered. Nonsurgical patients continued systemic therapy until disease progression or intolerance. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Cancer Hospital (approval No. 2019YJZ29-Z-ZY02) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Evaluation of tumor response was conducted through imaging every 9 weeks (± 7 days) starting from the initiation of therapy until week 48. Subsequently, the evaluation was performed every 12 weeks (± 7 days). Evaluation of tumor response was based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST). The treatment response was evaluated by assessing the sum of the diameters of the target lesion during the arterial enhancement phase throu

Total RNA was isolated from each sample (33 tumor samples) using the PureLink RNA Mini kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), and the purity and quality were measured by the Nanodrop spectrophotometer. RNA integrity was evaluated using the RNA Nano6000 Assay kit and the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Hiseq X10 platform. Raw reads were filtered by FastQC, and reads from three samples were not used in the subsequent analysis due to poor sequencing quality. The filtered reads were then aligned to the Ensembl human genome assembly GRCh37 using the STAR (ver. 2.7.0) with default parameters. Gene expression levels were analyzed by raw count and transcripts per kilobase million. Annotations of mRNA were retrieved from the GENCODE (ver. 19) database.

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the response and non-response group were screened by DESeq2 R package. The commonly used criteria for selection involved applying thresholds of |log2 (fold change)| > 1 and false discovery rate < 0.05. Genes with mean count < 1 among all samples were excluded. The processed raw counts were imported into DESeq2, and the normalization step was integrated into DESeq2 workflow.

The functional annotation for DEGs was performed by “clusterProfiler” R package. The Entrez-ID for each gene was transferred from gene symbols through “org.Hs.eg.db” for human tissues. Gene ontology terms were annotated using default parameters.

The xCell pipeline was utilized to determine the relative abundance of transcripts (measured in transcripts per kilobase million) for each sample. The immune cell infiltration score was calculated for down-stream analysis. The correlation analysis of DEGs was conducted using the Spearman correlation test on the R platform. Feature pairs with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the tumor tissues of 33 patients using the PureLink Genomic DNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Exome was captured using the Agilent SureSelect Human All ExonV5 kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Subsequent paired-end sequencing was performed on Illumina Novaseq6000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Clean reads were then aligned to the reference human genome hg19 (Genome Reference Consortium GRCh37) using the BWA (ver. 0.7.17). Somatic mutation calling was performed using the GATK MuTect2 pipeline on paired tumor and matched normal samples. To ensure high-confidence variant detection, additional stringent filtering criteria were applied: (1) Variants occurring more than twice in the panel of normals were excluded; (2) Candidate mutations were required to have a minimum of 10 supporting reads and a variant allele frequency (VAF) of ≥ 5%; (3) No more than three supporting reads were allowed in the matched normal control; and (4) The VAF in the tumor sample had to be ≥ 8 times higher than that in the normal control. Common germline mutations were filtered using the Genome Aggregation Database, and retained only if they had a sequencing depth of at least 50 × and a VAF greater than 30%.

Survival analyses were conducted separately for all differing factors identified in the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), immune microenvironment analysis, and WES analyses. Considering the significant influence of treatments following recurrence or progression on OS. PFS was defined as the time from the first dose of the study drug until the first occurrence of either: Disease recurrence (for patients who underwent resection) or disease progression (for patients who did not undergo resection). Additionally, to validate the results by expanding the sample size, sequencing data and survival outcomes from the liver HCC cohort were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and included in this study. Kaplan-Meier analysis was employed to explore the relationship between genes and prognosis.

The bioinformatics analysis was performed on the R platform (ver. 3.6.0). Fisher’s exact test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were utilized for comparing categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The influencing factors of PFS were analyzed by Cox univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between August 1, 2019 and November 25, 2021, 33 HBV-associated HCC patients were enrolled in the present study. At the data cutoff date (January 30, 2024), 12 patients underwent surgery with curative intent and one received radiofrequency ablation plus stereotactic radiotherapy due to the poor location that was inappropriate for resection. As of the data cutoff date, all remaining patients had discontinued the initial treatment. Fourteen discontinued due to disease progression; two completed treatment after 2 years and had no tumor residue as confirmed by needle biopsy; three discontinued due to adverse effects, and two because they withdrew their informed consent. Regrettably, 12 patients have died.

Twenty-two patients were assigned to the response group and 11 to the non-response group according to the mRECIST. Samples were prepared for each patient for further testing. However, three RNA-seq samples from the response group failed to pass quality control. As a result, only 30 samples (19 from response group and 11 from non-response group) were involved in the transcriptome analysis. Patients’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The age, BCLC stage, total number of tumors, size of tumors, and baseline alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level were not significantly different between the two groups. The number of patients who underwent surgery was higher in the response group than that in the non-response group, while the difference was not statistically significant. Female patients and those with ECOG performance status scores of 1 had a significantly higher likelihood of being non-responders (P < 0.05).

| Characteristic | Response group (CR + PR, n = 22) | Non-response group (SD + PD, n = 11) | P value |

| Median age (year) | 0.488 | ||

| < 60 | 13 (59) | 5 (46) | |

| ≥ 60 | 9 (41) | 6 (54) | |

| Sex | 0.033a | ||

| Male | 21 (95) | 7 (64) | |

| Female | 1 (5) | 4 (36) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.017a | ||

| 0 | 18 (82) | 4 (36) | |

| 1 | 4 (18) | 7 (64) | |

| BCLC stage | 1.000 | ||

| B | 11 (50) | 5 (45) | |

| C | 11 (50) | 6 (55) | |

| Tumor number | 1.000 | ||

| 1 | 12 (55) | 6 (55) | |

| 2-3 | 6 (27) | 3 (27) | |

| ≥ 4 | 4 (18) | 2 (18) | |

| Size of the largest tumor (cm) | 0.593 | ||

| < 5 | 3 (14) | 2 (18) | |

| 5-10 | 10 (45) | 3 (27) | |

| ≥ 10 | 9 (41) | 6 (55) | |

| Serum alpha-fetoprotein level | 0.488 | ||

| < 400 ng/mL | 13 (59) | 5 (45) | |

| ≥ 400 ng/mL | 9 (41) | 6 (55) | |

| Conversion to surgery | 0.132 | ||

| Yes | 11 (50) | 2 (18) | |

| No | 11 (50) | 9 (82) |

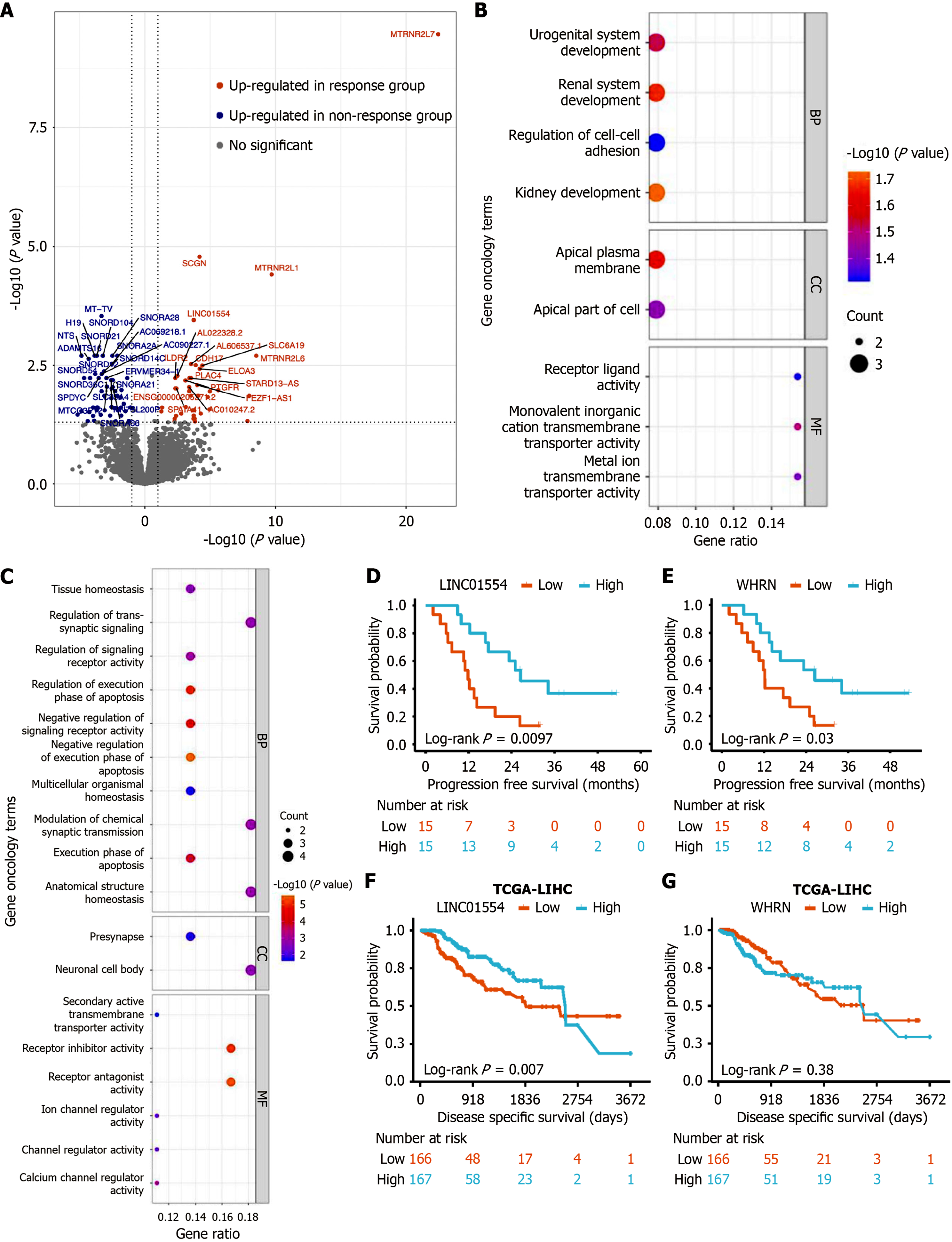

To identify molecular differences of HCC samples that caused different responses to treatment, DEGs were screened from RNA-seq data. Coverage and quality statistics for each sample are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Genes with low counts were filtered out and 32205 unique genes remained (54.01%). When comparing the response group with the non-response group, it was defined that a positive fold change indicated a higher expression in the response samples, while a negative value represented a lower expression. A total of 94 DEGs were found between the two groups [|log2 (fold change)| > 1, false discovery rate < 0.05]. Among them, 41 DEGs were enriched in the response group, while 53 DEGs were highly expressed in the non-response group (Figure 1A). Subsequently, the gene ontology enrichment annotations for each group provided insights into the potential functions of HCC baseline DEGs. In the non-response group, highly expressed genes were identified that were enriched in functions related to development and transmembrane (Figure 1B). In contrast, genes, which were highly expressed in the response group, were enriched in association with apoptosis process (Figure 1C).

Among the DEGs, two DEGs demonstrated a significant association with PFS. High expression levels of high long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 01554 (LINC01554) and whirlin (WHRN) were correlated with longer PFS and were predominantly expressed in the response group (Figure 1D and E). To further investigate the prognostic relevance of LINC01554 and WHRN in HCC, we expanded the sample size by analyzing data from the TCGA HCC cohort. The results showed that high expression of LINC01554 was significantly associated with improved OS in HCC patients (Figure 1F). In contrast, WHRN expression did not correlate with disease specific survival (Figure 1G). These findings suggest that LINC01554 expression is linked to the prognosis of HCC and highlight its potential as a molecular biomarker for response to sintilimab combined with lenvatinib for locally advanced HBV-associated HCC.

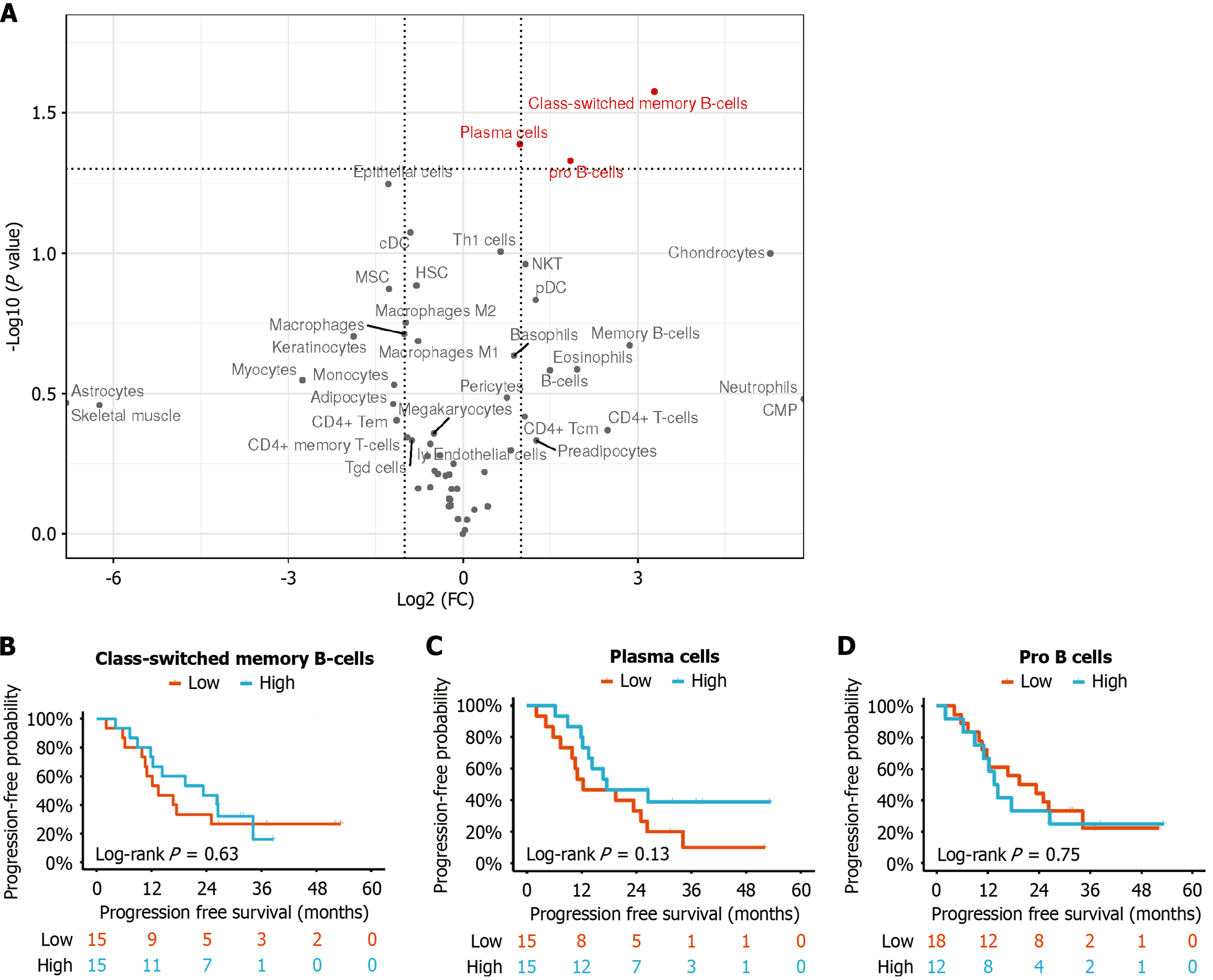

To reveal the underlying mechanisms driving varied responses to immunotherapy, xCell algorithm was used to calculate immune cell infiltration scores for each sample based on their baseline transcription expression. The immune microenvironment differences were described by comparing mean scores of each cell type between the response and non-response groups. The results showed that some cell types were more enriched in the response group, including pro-B cells, class-switched memory B cells, and plasma cells [t test P < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > 2]; all of which predominantly exhibited enrichment in B cell subtypes (Figure 2A).

In contrast, T cells did not show any specific preference in either group. Samples with infiltration scores greater than the median score across all samples were defined as high-score group. Unfortunately, the differences in the high or low scores of pro-B cells, class-switched memory B cells, and plasma cells did not reach statistical significance with respect to PFS (Figure 2B-D).

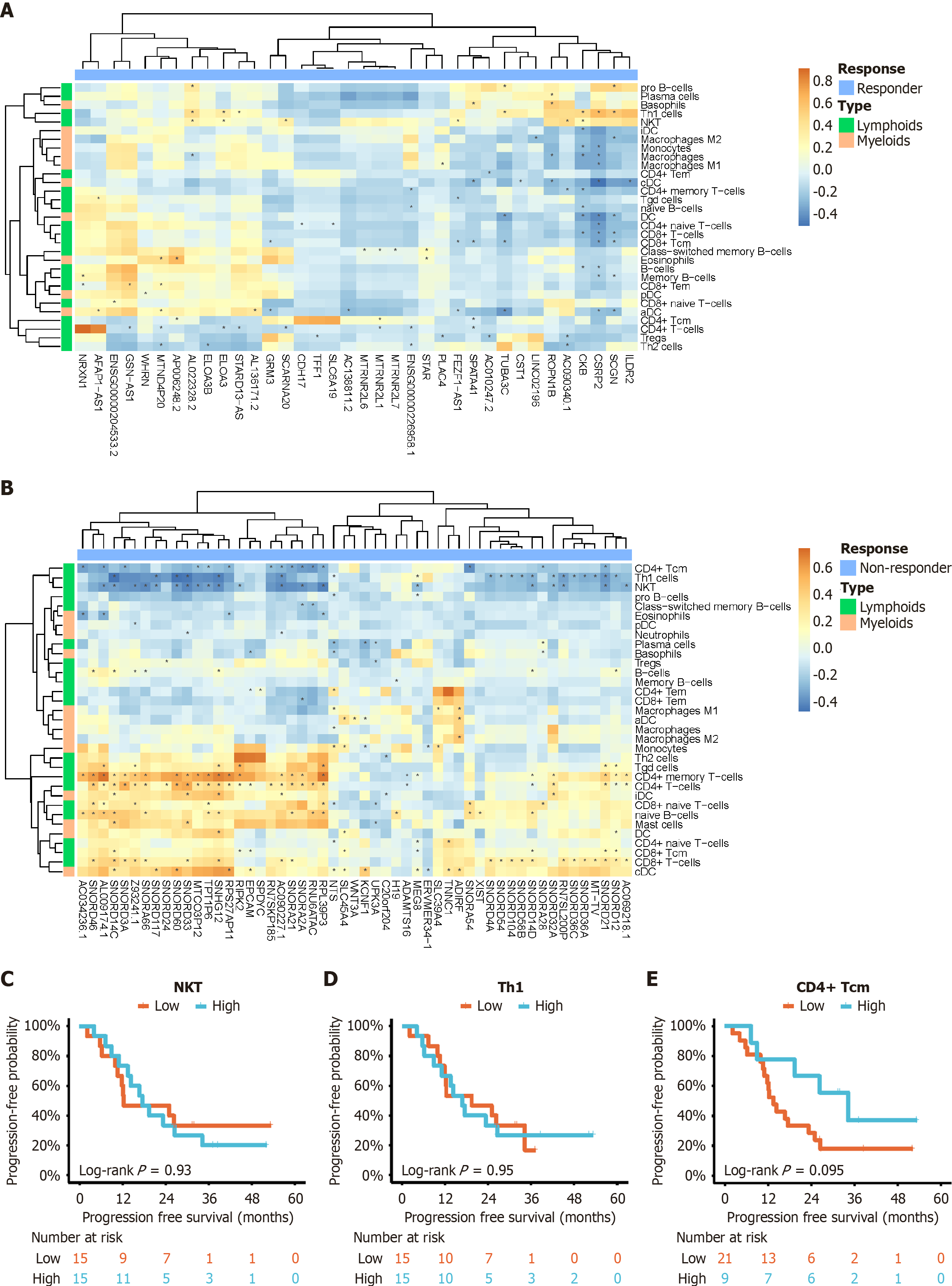

In order to examine the role of baseline gene expression in the diversity of the immune cell microenvironment, correlation analysis was performed between DEGs and immune cell infiltration scores. In the heatmap, feature pairs with P < 0.05 were identified using the Spearman correlation test, and these pairs were denoted with an asterisk. It was found that pro B-cells and plasma cells were positively correlated with highly expressed genes in the response group (Figure 3A), as described earlier (Figure 2A). T cells were negatively correlated with these genes. In contrast, the non-response group exhibited a different pattern, where various T cell subtypes showed variable correlations. In the non-response group, most of T cell subtypes were positively associated with highly expressed genes. However, three specific subtypes, namely CD4+ central memory T (Tcm) cells, T helper 1 cells, and natural killer T cells, demonstrated a negative correlation (Figure 3B). Similarly, expression differences in natural killer T, T helper 1, and CD4+ Tcm cells also failed to reach significance in relation to PFS (Figure 3C-E).

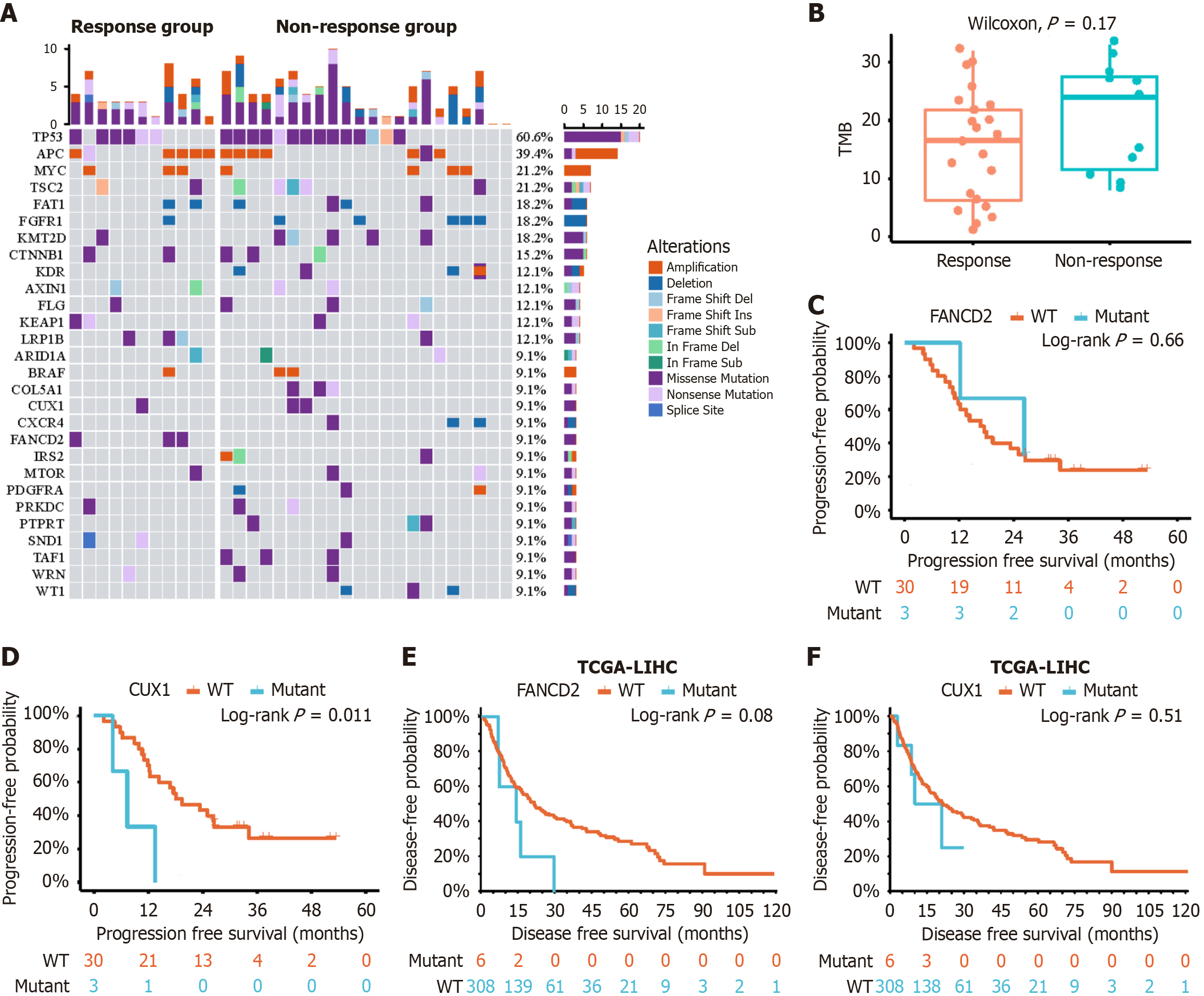

To investigate mutational landscape of HCC baseline tissues, WES was applied to all 33 baseline tissue samples (30 samples mentioned in RNA-seq analysis and three extra samples). Coverage and quality statistics for each sample are presented in Supplementary Table 2. These mutations included somatic single-nucleotide variants, deletion, insertion, and copy number variants (Figure 4A). The most frequent mutation across all samples was tumor protein p53 mutation (60.6%), followed by adenomatous polyposis coli (39.4%) and MYC (21.2%). The results of the Fisher’s exact test revealed that Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (FANCD2) was significantly mutated in the non-response group (P < 0.05). Five samples had beta-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations in the two groups. The immunological marker TMB - defined as the number of nonsynonymous somatic mutations (including single-nucleotide variants and small insertions/dele

To delve deeper into differences in baseline gene mutations and expression changes that contribute to disease progression, prognosis analysis was conducted on the WES mutations, immune cell infiltration scores, and RNA-seq read counts. We considered infiltration scores and expression levels that exceeded the median value of all samples as positive features. Features with < 3 positive samples in either group were filtered out. The analysis encompassed not only molecular biology findings, but also clinical features, such as age (≥ 60 year or < 60 years), gender (male or female), ECOG score (1 or 0), BCLC stage (B or C), tumor number (multiple or single), largest tumor size (≥ 10 cm or < 10 cm), and AFP level (≥ 400 ng/mL or < 400 ng/mL).

The results of univariate Cox regression analysis showed that tumor number, AFP level, mutational status of CUX1, expression of LINC01554, WHRN and CD4+ Tcm cells influenced duration of PFS (P ≤ 0.10). Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that single tumor [P = 0.02, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.31, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.11-0.85], high LINC01554 expression level (P = 0.01, HR = 0.16, 95%CI: 0.05-0.49), and higher CD4+ Tcm cell count (P = 0.05, HR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.08-0.98) were independent predictors of prolonged PFS (Table 2).

| Number | Univariate HR | P value | Multivariate HR | P value | |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 18/15 | 0.33 (0.14-0.78) | 0.01 | 0.31 (0.11-0.85) | 0.02 |

| AFP (< 400/≥ 400 ng/mL) | 18/15 | 0.49 (0.22-1.11) | 0.09 | - | - |

| CUX1 (wild/mutant) | 30/3 | 0.22 (0.06-0.79) | 0.02 | - | - |

| LINC01554 (high/Low) | 15/15 | 0.32 (0.13-0.79) | 0.01 | 0.16 (0.05-0.49) | 0.01 |

| WHRN (high/Low) | 15/15 | 0.39 (0.16-0.94) | 0.04 | - | - |

| CD4+ Tcm (high/Low) | 9/21 | 0.43 (0.16-1.19) | 0.10 | 0.29 (0.08-0.98) | 0.05 |

The present study revealed that combination of sintilimab and lenvatinib resulted in higher ORR and longer PFS. This makes it a viable treatment option for locally advanced liver cancer conversion therapy, which is widely implemented in clinical practice. Patients who have successfully undergone conversion to surgery experience two notable advantages compared with those who have not undergone conversion. First, they provide the potential for cure, and second, they facilitate avoiding prolonged drug treatments. PFS can vary among patients who are ineligible for surgery conversion. That is why screening and identifying patients who are more likely to benefit from conversion therapy in advance or identifying the population that can achieve longer disease control through combined treatments is important. For patients who are inappropriate candidates, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or other more intensive treatment options could be considered.

The accuracy of evaluating treatment response plays a vital role in the management of liver cancer patients. The mRECIST which consider tumor viability boundaries (particularly arterial-phase tumor enhancement) along with target lesion diameter, have gained widespread acceptance in post-treatment assessment of liver cancer[16]. Previous studies have demonstrated significant advantages of the mRECIST over RECIST (version 1.1) in assessing treatment response in liver cancer[17,18]. The mRECIST, with their stringent imaging standards, exhibited higher ORRs, improved discrimination for patients with stable disease, enhanced accuracy in evaluating study endpoints, and stronger predictive value for OS. Therefore, mRECIST can provide a more accurate assessment for patients with HCC undergoing systemic treatment[2]. In the present study, based on these criteria, patients were assigned to the response group and the non-response group.

Typically, the ORR of HCC patients receiving monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors is within 20%[19,20]. Molecular targeted drugs[10,21], such as bevacizumab, sorafenib, and lenvatinib may achieve the efficacy of rapid tumor killing, alteration of the tumor microenvironment, and synergistic enhancement of immune response by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor and its mediated tumor pathways. Consequently, addition of molecular targeted drugs effectively improved the ORR of treatment using immune checkpoint inhibitors. Due to the high heterogeneity of HCC and the presence of multiple factors influencing the response to the combined therapy, the present study comprehensively analyzed the factors affecting the efficacy through transcriptome sequencing, analysis of immune infiltration in tumor microenvironment, WES, and clinical data.

The key findings of this study highlight variations in RNA transcription levels between the response and non-response groups. By conducting functional screening of DEGs and analyzing their correlation with survival, two genes were identified, namely LINC01554 and WHRN, which displayed a strong association with treatment efficacy. LINC01554 has been consistently reported in multiple studies. According to a previous study[22], low expression of LINC01554 was linked to poor survival, advanced tumor stage, and the presence of portal vein tumor thrombus. In vitro experiments have revealed that high expression of LINC01554 partially inhibits the Wnt and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathways, resulting in reduced cell invasiveness and diminished epithelial-mesenchymal transition capability. Similarly, another study highlighted LINC01554, along with three other RNAs (transmembrane protein 220 antisense RNA 1, LINC02362, and LINC02499), as independent prognostic factors for HCC[23]. These consistent results suggest that LINC01554 is an important potential therapeutic target. The WHRN gene[24], which was also identified, is a protein-coding gene primarily associated with diseases, such as deafness, autosomal recessive, non-syndromic hearing loss, Usher syndrome type 2D, etc. However, few studies have concentrated on its involvement in tumor occurrence and development.

The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in exerting antitumor effects is influenced by the immune microenvironment. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that blocking the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 or PD-L2) can reactivate T-cell proliferation and cytokine release, enhance the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells, and promote the presence of memory CD4+ T cells[25-27]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues is closely associated with acceptable response of HCC patients receiving monotherapy (e.g., anti-PD-1 therapy)[28]. An important finding of this study is the identification of B-cell subtypes, rather than T cells, as being enriched in the response group through immune microenvironment analysis. We speculate that some B-cell subtypes may correlate with a good response to combination therapy. Recent research has reported the presence of tumor-infiltrating B cells as significant biomarkers of antitumor immune response in various types of tumors, supporting the role of B cells in responding to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy[29,30]. However, the exact mechanisms by which B cells contribute to antitumor immunity have not yet been fully explored. Some studies have suggested that B cells enhance T-cell immunity by secreting cytokines and chemokines, as well as expressing co-stimulatory signals[31,32]. In some physiological conditions, B cells may also act as primary antigen-presenting cells to initiate CD4+ T-cell responses[20]. Nevertheless, additional basic research is required to confirm these speculations. The analysis of the interaction between transcriptional RNA and immune cells in this study revealed that when tumors overexpressed specific genes (one or more of 41 DEGs) and were enriched with B cell subtypes in the immune microenvironment, a more favorable therapeutic response could be achieved. Conversely, when tumors overexpressed other specific genes (one or more of 53 DEGs), the influence of B-cell subtypes on treatment efficacy was limited, and different correlations were noted with T cell subtypes (particularly a negative correlation with CD4+ Tcm cells). Based on these immune findings, we hypothesize that the relationship between tumor-specific gene expression and efficacy is more crucial, while the immune microenvironment plays a secondary role, with B-cell subtypes and CD4+ Tcm cells, indicating a close association with satisfactory treatment response.

Although there were significant differences at the transcriptional RNA level between the response and non-response groups, no additional DEGs were detected in the WES except for the FANCD2 gene. Compared with the WES, which only detects exon fragments, RNA-seq includes more gene information, such as mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, and noncoding RNA. Therefore, it is noteworthy that gene mutations are not consistent between transcriptional RNA level and exon expression level. This phenomenon was also observed in a previous study[33]. Previous studies have shown that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its important protein CTNNB1 could be associated with poor response to immunotherapy[28,34]. However, in the present study, CTNNB1 mutations were distributed in both groups and did not reach significance. This may be related to the small sample size of mutated patients, and another possible reason is that a single gene or pathway mutation is insufficient to determine treatment efficacy. The addition of molecular targeted therapy may reverse the poor response to immunotherapy, and further large-scale studies are necessary to validate this hypothesis. In addition, another tumor marker, TMB, which has been validated as a predictor of response to immunotherapy in other tumor types, did not exhibit significant differences in this cohort. This suggests that the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects induced by the combination treatments are relatively complex, and a single immune-related marker may not accurately predict the response.

Consequently, the efficacy of the combination therapy using sintilimab and lenvatinib may be influenced by several factors, including the genetic status of the tumor, tumor immune microenvironment, and the patient’s clinical and pathological characteristics (e.g., gender, age, number and size of tumors). The results of the present study indicated a significant correlation between the high expression level of LINC01554 in tumor tissues, the high expression level of CD4+ Tcm cells in the immune microenvironment, and a solitary tumor (compared with multiple tumors) with prolonged PFS. The above-mentioned results strongly indicate that in cases of HCC, where specific mutations are identified through tumor biopsy and the immune microenvironment analysis shows favorable treatment response characteristics, even patients at advanced tumor stages may achieve extended disease control periods or successful conversion to surgical options. These significant findings have profound implications for guiding clinical treatment decisions.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, due to its small sample size, there might be the likelihood of selection bias among the enrolled patients. Secondly, HCC mainly consists of multiple subtypes and tissue components. Even with multiple samplings, there might be insufficient tissue volume, which could result in the inability of biopsy tissue testing to accurately reflect the overall biological characteristics of the tumor. Thirdly, the follow-up time was short, which might influence the results to some extent. Finally, no further mechanistic research and large-scale validation of the DEGs were conducted, and additional reliable studies are required to validate the findings of this research.

This study revealed that the response and non-response observed in HCC patients undergoing treatment with sintilimab plus lenvatinib were associated with variance in gene expression within liver cancer tissues and the distribution of lymphoid immune cells in the immune microenvironment. Preliminary analysis suggested that high expression levels of long noncoding RNA LINC01554 and CD4+ Tcm cells, as well as the presence of a solitary tumor, appeared associated with longer disease control duration in this cohort.

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their participation in this study. The authors also extend their sincere appreciation to Xiao-Ting Li, a statistician at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute (Beijing, China), for her sta

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56694] [Article Influence: 7086.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 2. | Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2800] [Cited by in RCA: 4367] [Article Influence: 545.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2184] [Cited by in RCA: 3125] [Article Influence: 446.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 4. | Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, Kudo M, Johnson P, Wagner S, Orsini LS, Sherman M. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35:2155-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 1016] [Article Influence: 92.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, Okusaka T, Kobayashi M, Kumada H, Kaneko S, Pracht M, Mamontov K, Meyer T, Kubota T, Dutcus CE, Saito K, Siegel AB, Dubrovsky L, Mody K, Llovet JM. Phase Ib Study of Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab in Patients With Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2960-2970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 154.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 5325] [Article Influence: 887.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (29)] |

| 7. | Wang L, Wang H, Cui Y, Liu M, Jin K, Xu D, Wang K, Xing B. Sintilimab plus Lenvatinib conversion therapy for intermediate/locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase 2 study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1115109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoy SM. Sintilimab: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2019;79:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Shi Y, Su H, Song Y, Jiang W, Sun X, Qian W, Zhang W, Gao Y, Jin Z, Zhou J, Jin C, Zou L, Qiu L, Li W, Yang J, Hou M, Zeng S, Zhang Q, Hu J, Zhou H, Xiong Y, Liu P. Safety and activity of sintilimab in patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (ORIENT-1): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e12-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, Lopez C, Dutcus C, Guo M, Saito K, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Ren M, Cheng AL. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4116] [Article Influence: 514.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 11. | Piñero F, Dirchwolf M, Pessôa MG. Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Response Assessment. Cells. 2020;9:1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:599-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 1463] [Article Influence: 182.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, Pikarsky E, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 1232] [Article Influence: 308.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Majewski J, Schwartzentruber J, Lalonde E, Montpetit A, Jabado N. What can exome sequencing do for you? J Med Genet. 2011;48:580-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10137] [Cited by in RCA: 8543] [Article Influence: 502.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3353] [Cited by in RCA: 3441] [Article Influence: 215.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (43)] |

| 17. | Kudo M, Montal R, Finn RS, Castet F, Ueshima K, Nishida N, Haber PK, Hu Y, Chiba Y, Schwartz M, Meyer T, Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Objective Response Predicts Survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Systemic Therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3443-3451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meyer T, Palmer DH, Cheng AL, Hocke J, Loembé AB, Yen CJ. mRECIST to predict survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of two randomised phase II trials comparing nintedanib vs sorafenib. Liver Int. 2017;37:1047-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A, Sarker D, Verset G, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Webber AL, Ebbinghaus SW, Ma J, Siegel AB, Cheng AL, Kudo M; KEYNOTE-224 investigators. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1184] [Cited by in RCA: 1982] [Article Influence: 247.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling TH Rd, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3278] [Cited by in RCA: 3454] [Article Influence: 383.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10533] [Article Influence: 585.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 22. | Li L, Huang K, Lu Z, Zhao H, Li H, Ye Q, Peng G. Bioinformatics analysis of LINC01554 and its coexpressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2020;44:2185-2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | He M, Gu W, Gao Y, Liu Y, Liu J, Li Z. Molecular subtypes and a prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma based on immune- and immunogenic cell death-related lncRNAs. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1043827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ebermann I, Scholl HP, Charbel Issa P, Becirovic E, Lamprecht J, Jurklies B, Millán JM, Aller E, Mitter D, Bolz H. A novel gene for Usher syndrome type 2: mutations in the long isoform of whirlin are associated with retinitis pigmentosa and sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2007;121:203-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, Fang Q, Huang L. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chikuma S, Terawaki S, Hayashi T, Nabeshima R, Yoshida T, Shibayama S, Okazaki T, Honjo T. PD-1-mediated suppression of IL-2 production induces CD8+ T cell anergy in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:6682-6689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bishop KD, Harris JE, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA, Czech MP, Phillips NE. Depletion of the programmed death-1 receptor completely reverses established clonal anergy in CD4(+) T lymphocytes via an interleukin-2-dependent mechanism. Cell Immunol. 2009;256:86-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Morita M, Nishida N, Sakai K, Aoki T, Chishina H, Takita M, Ida H, Hagiwara S, Minami Y, Ueshima K, Nishio K, Kobayashi Y, Kakimi K, Kudo M. Immunological Microenvironment Predicts the Survival of the Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Anti-PD-1 Antibody. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:380-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, Thakur R, Yizhak K, Sade-Feldman M, Blando J, Han G, Gopalakrishnan V, Xi Y, Zhao H, Amaria RN, Tawbi HA, Cogdill AP, Liu W, LeBleu VS, Kugeratski FG, Patel S, Davies MA, Hwu P, Lee JE, Gershenwald JE, Lucci A, Arora R, Woodman S, Keung EZ, Gaudreau PO, Reuben A, Spencer CN, Burton EM, Haydu LE, Lazar AJ, Zapassodi R, Hudgens CW, Ledesma DA, Ong S, Bailey M, Warren S, Rao D, Krijgsman O, Rozeman EA, Peeper D, Blank CU, Schumacher TN, Butterfield LH, Zelazowska MA, McBride KM, Kalluri R, Allison J, Petitprez F, Fridman WH, Sautès-Fridman C, Hacohen N, Rezvani K, Sharma P, Tetzlaff MT, Wang L, Wargo JA. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577:549-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 815] [Cited by in RCA: 1955] [Article Influence: 325.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Petitprez F, de Reyniès A, Keung EZ, Chen TW, Sun CM, Calderaro J, Jeng YM, Hsiao LP, Lacroix L, Bougoüin A, Moreira M, Lacroix G, Natario I, Adam J, Lucchesi C, Laizet YH, Toulmonde M, Burgess MA, Bolejack V, Reinke D, Wani KM, Wang WL, Lazar AJ, Roland CL, Wargo JA, Italiano A, Sautès-Fridman C, Tawbi HA, Fridman WH. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature. 2020;577:556-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 1413] [Article Influence: 235.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lund FE. Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes-key regulators of immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:332-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yan J, Harvey BP, Gee RJ, Shlomchik MJ, Mamula MJ. B cells drive early T cell autoimmunity in vivo prior to dendritic cell-mediated autoantigen presentation. J Immunol. 2006;177:4481-4487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhu AX, Abbas AR, de Galarreta MR, Guan Y, Lu S, Koeppen H, Zhang W, Hsu CH, He AR, Ryoo BY, Yau T, Kaseb AO, Burgoyne AM, Dayyani F, Spahn J, Verret W, Finn RS, Toh HC, Lujambio A, Wang Y. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med. 2022;28:1599-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 112.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Monga SP. β-Catenin Signaling and Roles in Liver Homeostasis, Injury, and Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1294-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/