Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.112315

Revised: August 14, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 9.6 Hours

Beyond its traditional role in calcium and bone metabolism, vitamin D has emer

Core Tip: Vitamin D plays diverse roles in chronic liver disease beyond bone health, including modulation of fibrosis, immune responses, bile acid metabolism, and oxidative stress via vitamin D receptor signaling. Deficiency is common across liver disease etiologies and linked to worse outcomes. Although preclinical data are promising, clinical trials have yielded inconsistent results. This review summarizes the mechanistic and clinical evidence for vitamin D in autoimmune, viral, alcoholic, and metabolic liver diseases, emphasizing its potential as a modifiable factor and the need to define patient subgroups most likely to benefit from supplementation.

- Citation: Guerrero-Guerrero R, Mendez-Guerrero O, Carranza-Carrasco A, Tejeda F, Ardon-Lopez A, Navarro-Alvarez N. Beyond bones: Revisiting the role of vitamin D in chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 112315

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/112315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.112315

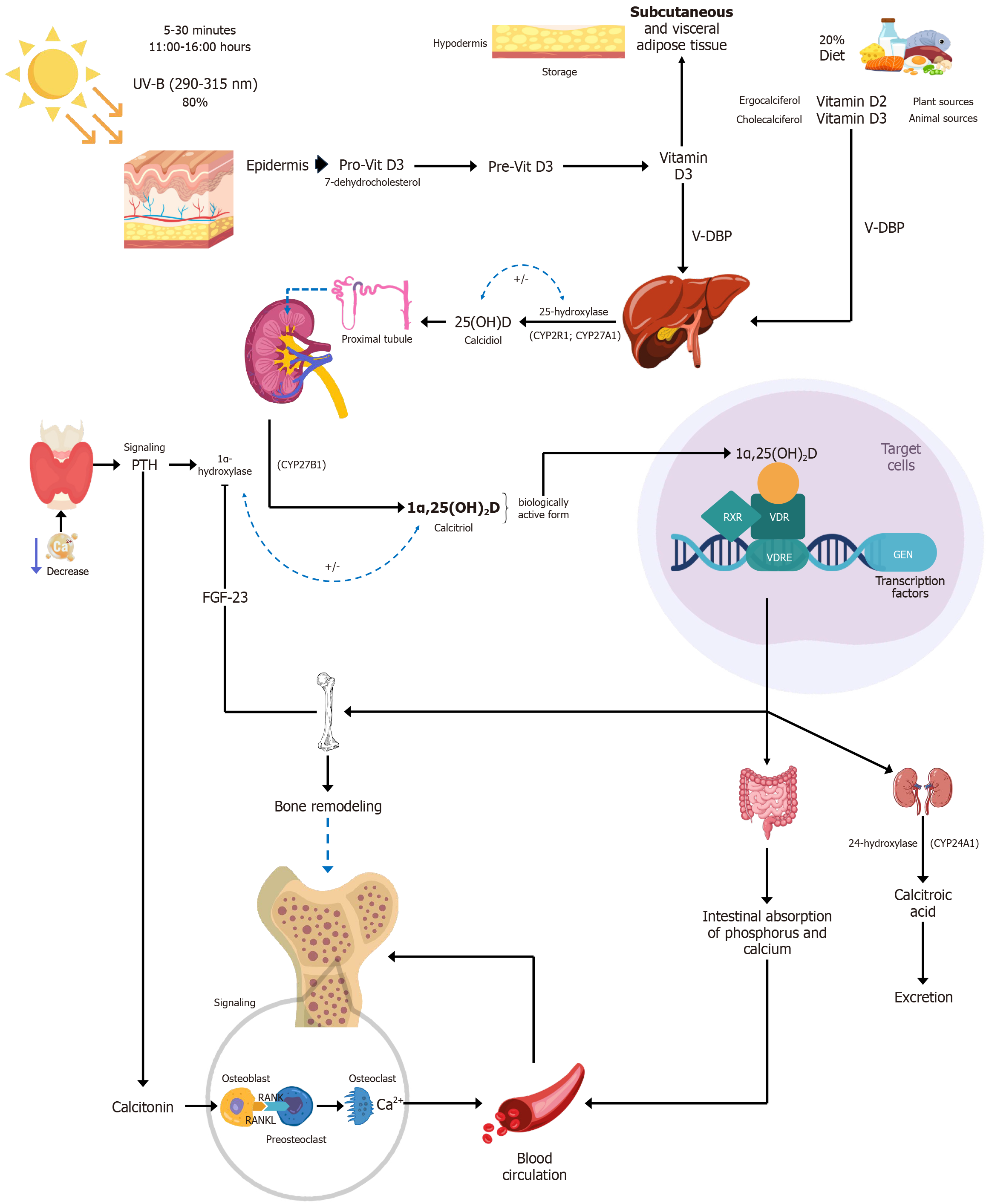

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble steroid that plays a crucial role in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis, bone health, insulin secretion, and immune system function[1]. It is also considered a prohormone, as the body converts it into its active form: Calcitriol or 1α,25(OH)2D, which regulates numerous physiological processes[2]. Vitamin D can be found in two main forms. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), of animal origin, is the most significant source in humans. It is synthesized in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol upon exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol), of plant origin, is derived from ergosterol, a precursor produced by fungi and plants[1,3]. Both vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 follow the same metabolic pathway in the body[4].

Vitamin D is obtained from two primary sources: Sunlight exposure and diet. Upon ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure (wavelength 290-315 nm), 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin is photochemically converted into previtamin D, which is then thermally isomerized into vitamin D[5]. Dietary vitamin D is absorbed primarily in the jejunum and, to a lesser extent, in the duodenum[6], encapsulated in chylomicrons and released into the bloodstream[7]. Afterward, vitamin D is tran

Calcitriol then enters the circulation and, after binding to VDBP, is delivered to target tissues[10]. In these tissues, calcitriol binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), a member of the nuclear receptor family of ligand-activated transcription factors, inducing both genomic and non-genomic regulation of downstream targets involved in various biological functions. Calcitriol can rapidly diffuse across cell membranes and bind VDRs. Once bound to its ligand, the VDR forms heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and translocates to the nucleus, where the complex binds to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) to regulate gene transcription[11].

Once both calcidiol and calcitriol are produced, their levels are tightly regulated by 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1), the primary enzyme responsible for vitamin D inactivation. This enzyme catalyzes the hydroxylation reactions of both calcidiol and calcitriol, particularly at position 24 (C-24) of calcitriol, leading to a series of reactions that ultimately generate calcitroic acid, an inactive metabolite excreted via the bile[8,9].

In addition to CYP24A1-mediated regulation, vitamin D metabolism is modulated by two key hormones: Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and FGF23. Both are essential for maintaining calcium and phosphate homeostasis[12-14]. In response to hypocalcemia, PTH is released and stimulates the conversion of calcidiol into calcitriol in the kidneys by CYP27B1. Calcitriol, in turn, enhances intestinal calcium absorption, contributing to the normalization of serum calcium levels and supporting bone health, one of the major physiological roles of vitamin D[15]. FGF23 is secreted by osteoblasts and osteocytes in response to elevated serum phosphate and calcium levels[14]. It reduces serum calcitriol levels by inhibiting the expression of CYP27B1 while stimulating CYP24A1 expression in the kidney, although the mechanisms behind these actions are not yet fully understood[16-18] (Figure 1). Some studies suggest that 7-dehydrocholesterol and vitamin D3 may follow an alternative metabolic pathway, as they are substrates for CYP11A1, but further research is needed to fully elucidate this mechanism[19,20].

Vitamins D2 and D3 are fat-soluble, and are stored in adipocytes (fat cells), especially in individuals with obesity. Although people with obesity may have larger total vitamin D stores, these are less bioavailable and are not readily reflected in circulating blood levels[7]. The conversion of vitamin D2 and D3 into calcidiol [25(OH)D] usually occurs efficiently, but this process is impaired in obesity due to reduced expression of CYP2R1, the enzyme responsible for the first hydroxylation step. As a result, vitamin D3 levels remain disproportionately high, while calcidiol levels are often lower compared to those in healthy individuals, despite greater vitamin D storage[7].

Vitamins D2 and D3 have a short half-life of approximately 24 hours[7], while calcitriol [1α,25(OH)2D], the active form of vitamin D, has an even shorter half-life of 4-15 hours[7,21-23]. In contrast, calcidiol [25(OH)D], the main circulating metabolite, has a much longer half-life of about 2-3 weeks[7,21,22,24]. Due to this longer duration and its ability to reflect both dietary intake and sunlight exposure, serum calcidiol is the most reliable and commonly used biomarker for assessing vitamin D status in clinical practice. Measuring calcitriol levels in contrast, is more technically complex and expensive[7,23,25,26].

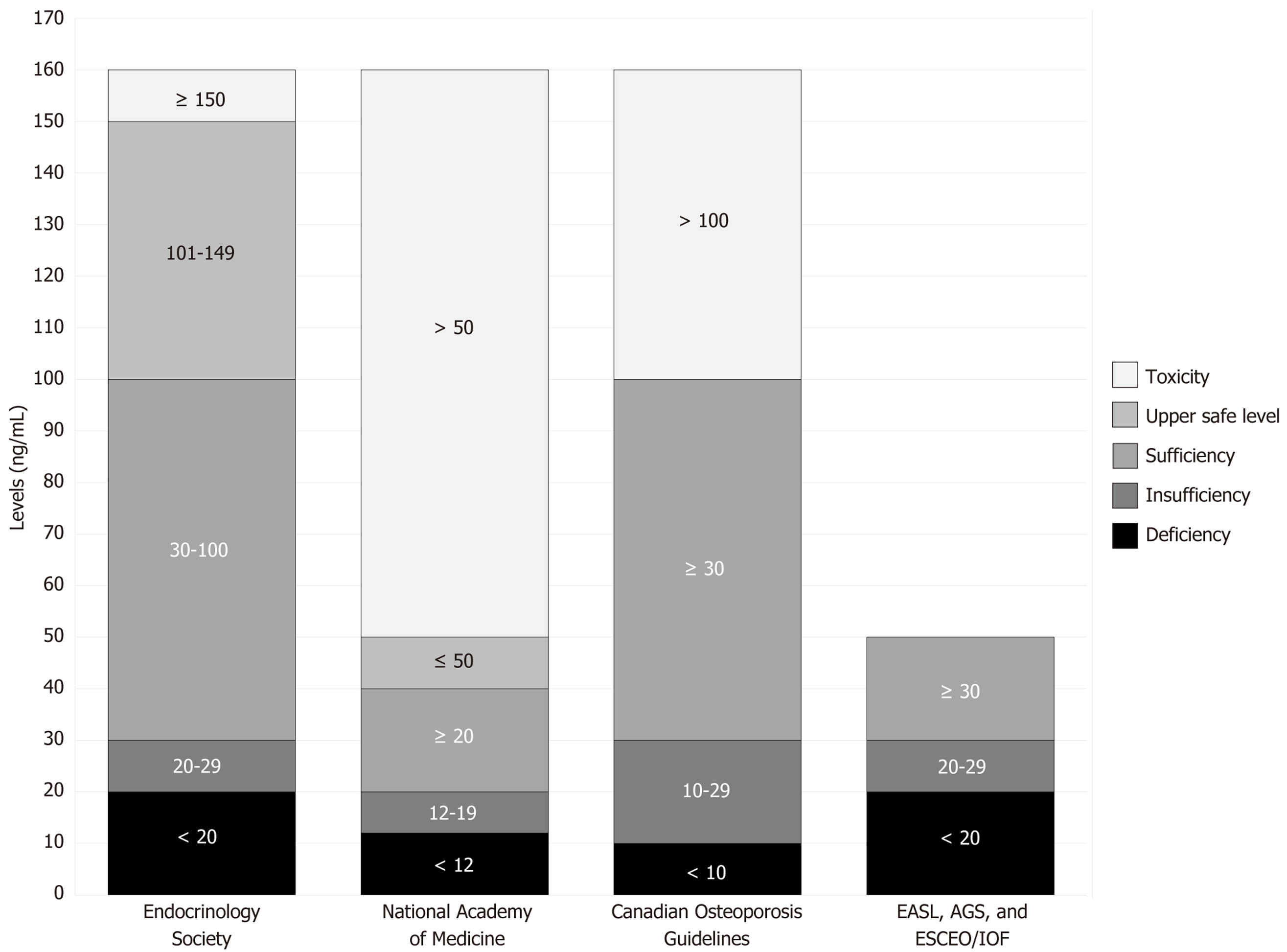

Currently, there is no universal consensus on the exact optimal range for vitamin D levels. Figure 2 presents a comparison of thresholds proposed by different institutions regarding adult serum levels of vitamin D (specifically calcidiol).

Although these recommendations differ slightly, especially in defining toxicity[21,27-29], the general thresholds for deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency are fairly consistent[30-32]. These variations may reflect population-specific characteristics, but the average values can serve as a useful reference for broader application.

The functions of vitamin D include bone growth and mineralization, regulation of immune function, control of insulin secretion, regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation, induction of apoptosis, and maintenance of calcium-phosphorus homeostasis, including calcium transport in muscle cells[11].

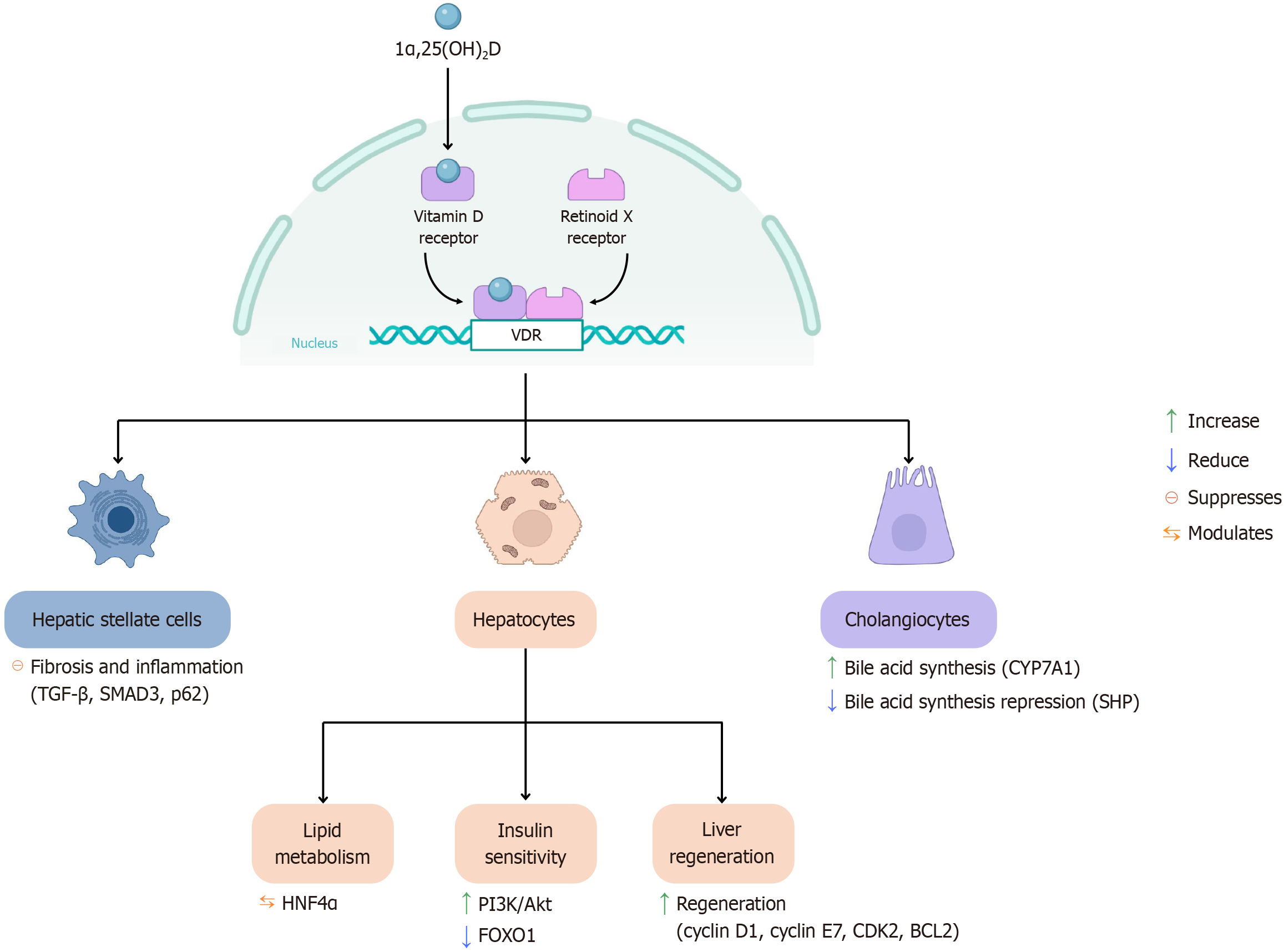

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in maintaining liver health, particularly through its active form, 1α,25(OH)2D, which exerts its biological effects by binding to the VDR. In the liver, the VDR is primarily expressed in non-parenchymal cells, including Kupffer cells, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and cholangiocytes[33]. One of the key hepatic functions of vitamin D is the regulation of immune responses. Through VDR-mediated signaling, vitamin D helps modulate inflammation, protect against tissue injury, and inhibit the development of hepatic fibrosis[34]. These mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 3.

The binding of calcitriol to VDR can activate both genomic and non-genomic pathways. For genomic activation, calcitriol first enters the cell and binds to inactive VDR located in the cytoplasm[35]. VDR contains a ligand-binding domain which includes a ligand-binding pocket where calcitriol docks, inducing conformational changes. This structural shift enables VDR to heterodimerize with RXR, forming the VDR-RXR complex[36]. The complex then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to VDREs within the promoter regions of target genes. This interaction recruits co-activator proteins such as histone acetyltransferases which modify chromatin to enhance gene transcription. Subsequently, the mediator complex and RNA polymerase II are recruited, leading to the transcription of genes involved in immune regulation, cell proliferation, and differentiation[35].

In contrast, the non-genomic pathway is initiated when calcitriol binds to membrane-associated VDR. This activates GPCRs, resulting in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ through calcium channels. The elevated Ca2+ levels trigger down

VDR also interacts with HNF4α, a key regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism and triglyceride transport. This interaction has been shown to reduce lipid accumulation in the liver, particularly in high-fat-diet mouse models[37]. The vitamin D-VDR complex improves hepatic insulin sensitivity by enhancing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, suppressing FOXO1-mediated gluconeogenesis, and mediating the metabolic benefits of vitamin D. In liver regeneration, the VDR complex is essential following hepatic injury. It regulates the expression of cell-cycle genes such as cyclin D1, cyclin E1, and Cdk2, as well as the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl2, thus promoting hepatocyte survival and coordinated regeneration[38].

In HSC which are the primary drivers of fibrosis upon liver injury, VDR activation counteracts the pro-fibrogenic effects of TGF-β, a major HSC activator. In the absence of VDR, SMAD2 phosphorylation increases, enhancing the transcription of fibrogenic genes[39]. Interestingly, there is a regulatory mechanism in hepatic fibrogenesis in which initial SMAD3 activation is paradoxically required for later suppression of fibrotic gene expression. First, SMAD3 phosphorylation by TGF-β remodels chromatin, enabling VDR access. Then, VDR displaces SMAD3 and suppresses profibrotic gene transcription. This mechanism helps explain how VDR signaling modulates wound-healing responses in the liver[40]. In addition, p62, a scaffold protein that activates stress-responsive transcription factors (NRF2 and NF-κB), binds to VDR in HSCs, enhancing the VDR-RXR complex formation. This interaction is critical for VDR-mediated repression of fibrosis and inflammation[41]. Conversely, the absence of VDR increases the NF-κB activation and upregulates the expression of fibrosis-related genes[42].

In Kupffer cells (liver-resident macrophages), hepatocyte-derived danger signals and apoptotic bodies released during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress activate the unfolded protein response via the IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 sensors. These pathways trigger IKK-NF-κB signaling, resulting in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. The vitamin D-VDR complex in Kupffer cells exerts strong anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB activation, thereby reducing cytokine production. When VDR signaling is active, it helps resolve both the ER stress and the inflammatory response[43,44].

Vitamin D also influences adaptive immunity. The vitamin D-VDR complex modulates T cell receptor signaling, suppresses T cell activation and proliferation, and inhibits Th1-type cytokine production[45]. It induces tolerogenic dendritic cells, promotes Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), inhibits Th17 responses, and enhances Th2 cell polarization[46-48]. Together, these immunomodulatory effects contribute to attenuating hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis, reinforcing the importance of adequate vitamin D levels in maintaining liver immune homeostasis and preventing disease progression.

In cholangiocytes, which line the bile ducts, VDR can be activated by lithocholic acid, a secondary bile acid (BA), and its derivatives.

Activation of the vitamin D-VDR complex increases CYP7A1 expression (rate-limiting enzyme in bile acid synthesis) and decreases the expression of small heterodimer partner, a nuclear receptor that normally represses BA synthesis[49]. These findings suggest that VDR plays a complex regulatory role, capable of modulating BA homeostasis by shifting the balance between synthetic and inhibitory pathways under specific pathological conditions. VDR deletion in mice leads to reduced BA pool size and worsens cholestatic injury[38].

In Abcb4 knockout mice, a model for chronic cholangiopathy, VDR ablation (VDR-/-; Abcb4-/-) exacerbates liver disease, promotes cholangiocyte proliferation, and increases chemokine expression (CCL2 and CCL20), amplifying macrophage recruitment and liver inflammation[50].

Vitamin D can be obtained from two main sources: Sunlight exposure and diet. The majority (up to 80%) comes from skin synthesis triggered by sunlight, while the remaining 20% is derived from dietary intake[21]. The amount of vitamin D needed to maintain proper physiological function varies depending on age, sex, and individual characteristics. Table 1 presents the estimated average requirement and the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) established by the United States National Academy of Medicine. Vitamin D intake is typically measured in micrograms (µg) or international units (IUs), with 1 µg equivalent to 40 IU[28,51].

| Group | EAR (IU) | RDA (IU) |

| Men (year) | ||

| 19-70 | 400 | 600 |

| > 70 | 400 (10 μg) | 800 (20 μg) |

| Women (year) | ||

| 19-70 | 400 (10 μg) | 600 (15 μg) |

| > 70 | 400 (10 μg) | 800 (20 μg) |

Most people worldwide meet at least part of their vitamin D needs through sun exposure. Factors influencing UVB exposure include season, geographic location, time of day, cloud cover, skin pigmentation, and sunscreen use. Older adults and individuals with darker skin produce less vitamin D from sunlight[51]. UVB does not penetrate glass, so sunlight exposure through windows does not result in vitamin D synthesis[52].

Guidelines recommend 5-30 minutes of direct sun exposure in the morning, with sunscreen applied afterward[53,54]. This can generate up to 3000 IU of vitamin D[54].

Only a few foods naturally contain vitamin D. Fatty fish and fish liver oils, such as trout, salmon, tuna, and mackerel, are the best natural sources. Beef liver, egg yolk, and cheese contain smaller amounts. Vitamin D in animal tissues varies with diet[51,55]. Taking vitamin D supplements with fat-containing meals improves absorption[56,57]. Table 2 lists selected foods and their vitamin D content per 100 g[58]. Dietary intake alone is usually insufficient, especially for those following plant-based diets or facing geographic or socioeconomic limitations.

| Foods | μg/100 g | IU/100 g |

| Cod liver oil | 250 | 10000 |

| Raw mackerel | 16.1 | 644 |

| Raw salmon | 10.9 | 436 |

| Canned sardines | 4.8 | 192 |

| Raw trout | 3.9 | 156 |

| Raw tuna | 1.7 | 68 |

| Egg (yolk) | 5.5 | 220 |

| Margarine | 3.7 | 148 |

| Beef liver | 1.2 | 48 |

| Yogurt, skim milk | 1.2 | 48 |

| Low-fat milk | 1 | 40 |

| Cheddar and feta cheese | 0.5 | 20 |

| Butter | 0.4 | 16 |

| Orange juice | 1 | 40 |

| Raw shiitake mushrooms | 0.5 | 20 |

| Soy milk | 0.7 | 28 |

Therefore, it is important to combine dietary intake with safe sun exposure, always following established guidelines to protect skin from damage.

Vitamin D is most commonly administered as cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), though other formulations such as ergocalciferol (vitamin D2), eldecalcitol, and calcifediol, are also available. Cholecalciferol is widely used because its dosage correlates with changes in blood levels of calcidiol [25(OH)D], which is the standard biomarker for assessing vitamin D status and is associated with key clinical outcomes[21].

The RDA is 400-800 IU/day, with a tolerable upper limit of 4000 IU/day. However, the optimal dose may vary depending on the intended health outcome, and some authors suggest that the safer upper limit may actually be lower than 4000 IU per day[59,60]. For instance, 400-800 IU daily may be sufficient to prevent clinical deficiency and maintain calcium homeostasis in healthy individuals.

On the other hand, doses exceeding the recommended upper limit may pose a risk of toxicity. Nevertheless, daily doses as high as 10000 IU have been used without safety concerns in some studies[61]. It is important to note that there is no universally accepted consensus on the ideal vitamin D supplementation regimen, as individual factors significantly influence baseline vitamin D levels and requirements.

Before initiating supplementation, serum calcidiol [25(OH)D] should be measured. Table 3 summarizes findings from several studies evaluating vitamin D supplementation in various liver diseases. More evidence is needed before drawing definitive conclusions about the effect of vitamin D supplementation on liver disease. Additional randomized clinical trials are required to assess longer treatment durations, different formulations of vitamin D (e.g., cholecalciferol vs calcidiol), and larger, more diverse patient populations. Without these elements, it may be difficult to detect meaningful effects, whether beneficial or potentially harmful, of the intervention.

| Ref. | Population | Type of study | Intervention | Outcomes |

| Mohamed et al[153], 2021 | 328 patients with SBP (168 control group vs 160 supplementation group), aged over 18 years | RCT | Supplementation: 300000 IU of cholecalciferol as a loading dose via intramuscular injection, followed by a maintenance dose of 800 IU/day orally, plus oral calcium supplements at a dose of 1000 mg. Duration: 6 months | (1) Increased serum vitamin D levels in the treatment group (P < 0.001); (2) Higher survival rate (64% vs 42%; P < 0.05); and (3) Association between vitamin D supplementation and 6-month survival (HR = 0.895, P < 0.001) |

| Kim et al[165], 2018 | 548 patients with chronic HCV (7 RCTs), aged 7-42 years | Meta-analysis | Supplementation: (1) 6 studies used: 1000/1600/2000 IU daily of cholecalciferol; and (2) 1 trial used: 15000 IU weekly of cholecalciferol. Duration: 24 weeks of pegylated interferon alpha and RBV (Peg-IFN-α + RBV) antiviral treatment | (1) Combination of Peg-IFN-α + RBV significantly increased the sustained virological response rate at 24 weeks (RR = 1.30; 95%CI: 1.04-1.62); and (2) Greatest efficacy observed in patients with HCV genotype 1 |

| Hariri and Zohdi[166], 2019 | 353 patients with MASLD (6 RCTs), aged over 18 years | Systematic review | Supplementation: (1) 4 trials with: 50000 IU of cholecalciferol weekly; (2) 1 trial with: 2000 IU/day of cholecalciferol; and (3) 1 trial with: 25 µg of calcitriol/day. Duration: 6-24 weeks | (1) Improved lipid profile and inflammatory mediators compared to placebo; and (2) Reduction in liver enzymes when combined with calcium carbonate |

| Grover et al[167], 2021 | 164 patients with cirrhosis of any etiology (82 control group vs 82 supplementation group), aged 18-60 years | RCT | Supplementation: 60000 IU of cholecalciferol weekly for the first 2 months, followed by 60000 IU monthly for 10 months. Duration: 1 year | Significant increase in 25(OH)D levels in the intervention group compared to placebo |

| Kong et al[168], 2022 | 104363 participants (32 RCTs), mostly women, aged 53-85 years | Meta-analysis | Supplementation: 800-4000 IU of cholecalciferol/day. Duration: Follow-up from 9 to 120 months | Significant reduction in risk of falls (RR = 0.91) and osteoporotic fractures (RR = 0.87) |

| Sakpal et al[169], 2017 | 81 patients with MASLD (40 control group vs 41 supplementation group), aged 18-70 years | RCT | Supplementation: 600000 IU of vitamin D via a single injection, along with lifestyle modifications (exercise and diet). Duration: 6 months | (1) Significant improvement in ALT levels (87 ± 48 IU/mL to 59 ± 32 IU/mL, P < 0.001) compared to the control group (64 ± 35 to 62 ± 24 IU/mL, P = 0.70); and (2) Significant increase in adiponectin levels |

| Goto et al[170], 2022 | Male Wistar rats (four groups of 5-8 rats), 6 weeks old | Preclinical experimental model | Supplementation: 5000 IU/kg and 10000 IU/kg of cholecalciferol in the diet. Duration: 25 weeks | (1) Reduction in hepatic collagen deposition and inflammation; (2) Increased antioxidant activity and Nrf2 protein in the liver; and (3) Higher dose (10000 IU/kg) reduced the number of hepatic adenomas and preneoplastic lesions |

Vitamin D deficiency should be suspected in patients with liver disease, especially in advanced stages of the disease and in those with alcoholic liver disease, metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), or autoimmune conditions such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)[62]. Certain physiological conditions are also associated with an increased risk of deficiency, including postmenopausal status, advanced age, and malnutrition (sarcopenia), as well as clinical features such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, bone or muscle pain, hair loss, delayed wound healing, and frequent falls, all of which may be worsened by inadequate vitamin D levels[21]. Guidelines recommend supplementation in patients with docu

In general, supplementation with vitamin D is recommended for all patients with liver disease of any etiology who present with serum vitamin D levels below 20 ng/mL[64], aiming to reach concentrations above 30 ng/mL. To achieve this, a daily dose of 400-4000 IU of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is recommended, adjusted based on individual clinical characteristics. Patients with a bone densitometry T-score below -1.5 standard deviations should initiate supplementation with calcium (1000-1500 mg/day) and vitamin D (400-800 IU/day)[30].

Vitamin D supplementation in patients with liver disease may be particularly beneficial during the early stages of the disease, as it allows for more effective clinical benefits and timely correction of deficiency[65]. However, evidence regarding its impact on the progression of liver disease is still limited. Therefore, in patients with low serum vitamin D levels, supplementation may provide benefits for both skeletal health and liver function[66].

Finally, various medications can alter vitamin D metabolism, affecting absorption and bioavailability. Table 4 outlines the most relevant examples[21,67,68].

| Clinical factors | Pharmacological factors |

| Liver dysfunction | Long-term therapy with antiepileptic drugs: Phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone. These can decrease vitamin D levels and increase the risk of bone health problems |

| Chronic kidney failure | Orlistat: May reduce the absorption of vitamin D from food and supplements by blocking fat absorption |

| Inherited disorders of vitamin D metabolism | Corticosteroids: May reduce calcium absorption and impair vitamin D metabolism |

| Therapy for people with obesity or gastric bypass | Thiazide diuretics: Excessive vitamin D supplementation may cause hypercalcemia because thiazides decrease urinary calcium excretion |

| Gastrointestinal diseases: Hepatobiliary disease, malabsorption, chronic pancreatitis, celiac disease | Bile acid sequestrants: Cholestyramine and colestipol. They may impair vitamin D absorption |

Vitamin D deficiency is a common finding not only in non-hepatic autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis[69,70], but also in autoimmune liver diseases, including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), PBC and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)[62,71].

AIH is a chronic, progressive liver disease[72] in which vitamin D may influence disease severity. Several studies have investigated this association. For instance, Efe et al[73] reported significantly lower serum vitamin D levels in AIH patients compared to healthy controls (16.8 ± 9.2 vs 35.7 ± 13.6, P < 0.0001).

PBC is a chronic autoimmune cholestatic liver disease characterized by ductal epithelial damage and progressive fibrosis, which can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, and the need for a liver transplant[74,75]. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in PBC, and decreasing levels may indicate disease progression[76].

In addition, impaired osteoblast function has been observed in patients with PBC[68,77] along with a reported association between vitamin D deficiency and increased risk of osteopenia or osteoporosis[70]. Osteoporosis is particularly prevalent in postmenopausal women with PBC, leading to a higher risk of bone fractures[78,79].

In 2019, Ebadi et al[80] reported that AIH patients with severe vitamin D deficiency (< 25 nmol/L) had an increased risk of mortality and disease progression. They also reported that vitamin D levels below 50 nmol/L were associated with increased risk of cirrhosis and liver-related mortality[75,81], supporting the idea that higher vitamin D levels may have a protective effect in PBC[82].

A reduction in the vitamin D-VDR/miRNA 155-SOCS1 axis (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1) has been proposed to contribute to insufficient downregulation of cytokine signaling, playing a role in PBC pathogenesis[83]. Additionally, proinflammatory cytokines have been implicated in the loss of bone mass observed in these patients[84]. Furthermore, vitamin D plays a vital role in T cell-mediated immunity. It can reduce the accumulation of proinflammatory CD28+ T cells in the livers of PSC patients. These T cells have been found clustered around bile ducts, suggesting that vitamin D may modulate immune-driven bile duct injury in PSC[85].

Chronic alcohol abuse or excessive long-term consumption leads to alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD)[86]. The pathogenesis of ALD is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, alcohol-induced hepatocellular injury, oxidative stress, and gut-derived microbial components. These factors contribute to hepatic steatosis and promote the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells within the liver[87].

A prospective study found that higher serum concentrations of 25(OH)D were associated with lower Child-Pugh scores in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, suggesting a potential link between vitamin D status and disease severity[88]. Another cohort study showed that vitamin D deficiency worsens ALD pathogenesis by compromising intestinal barrier function and increasing hepatic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels[81].

Excessive alcohol intake disrupts tight junctions in the intestinal epithelium, leading to increased intestinal permeability and translocation of gut-derived endotoxins, such as LPS[89]. Once in the liver, LPS activates Kupffer cells (liver-resident macrophages) via the TLR4 signaling pathway, promoting the release of proinflammatory cytokines[90]. Therefore, preserving the integrity of the intestinal barrier and limiting LPS translocation to the liver may help mitigate alcohol-induced liver injury[81].

In addition, a case-control study reported significantly lower serum calcidiol [25(OH)D] levels in patients with alcoholic liver disease, and proposed that calcidiol may serve as a protective factor in this context[91].

Vitamin D is involved in the pathogenesis of chronic liver diseases caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). A high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, defined as serum levels below 20 ng/mL, has been reported in patients with these infections. Several studies suggest that maintaining adequate vitamin D levels may enhance antiviral treatment responses in both HBV and HCV infections[92].

In cases of viral cirrhosis, particularly among postmenopausal women, elevated serum levels of sTNFR-55 have been observed in patients with osteoporosis. These levels are inversely correlated with bone mineral density, suggesting a potential link between chronic inflammation, bone loss, and vitamin D status in this population[93].

Several studies have demonstrated that serum levels of calcidiol [25(OH)D] are significantly lower in patients with chronic hepatitis B compared to healthy individuals. Moreover, vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with reduced suppression of HBV replication, suggesting a potential role in modulating viral activity[94,95].

Additional evidence suggests that calcitriol [1α,25(OH)2D] directly inhibits HBV by interfering with viral protein production and reducing HBV replication rates[94,96,97].

In vitro studies support the role of vitamin D in chronic hepatitis C, showing it can act as suppressor of HCV replication[98,99]. Vitamin D also modulates necroinflammatory and fibrotic processes associated with HCV infection[100,101].

Mechanistically, vitamin D binding to the VDR helps regulate HCV inflammation by suppressing the TLR/NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulating proinflammatory gene expression. Additionally, calcitriol impacts HCV pathogenesis by activating VDR and inhibiting the activity of PPAR-α/β/γ[34]: (1) Repression of PPAR-α/γ inhibits viral infection; (2) Repression of PPAR-β/γ reduces nitrosative stress (i.e., excess reactive nitrogen species); and (3) Repression of PPAR-γ decreases hepatic lipid accumulation.

Although vitamin D may positively influence the progression of viral hepatitis and response to antiviral therapy, the exact mechanisms are not fully understood. Some clinical studies report no significant effect on serum markers of hepatic fibrogenesis after supplementation. Therefore, additional research is needed to clarify its therapeutic role[102,103].

MASLD is an increasingly prevalent condition characterized by abnormal fat accumulation in the liver, often linked to underlying metabolic disorders such as obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia[104]. Once MASLD develops, it can lead to hepatic insulin resistance, promoting metabolic-associated steatohepatitis. This can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[105-107].

Vitamin D plays a key role in regulating adipose tissue (AT) inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, abnormal lipid accumulation, and insulin resistance[108-112]. Deficiency of vitamin D has been linked to insulin resistance-related disorders, including type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and MASLD[113]. Multiple studies have reported that vitamin D deficiency is common in adults with MASLD[114-117] and is often correlated with both disease presence and severity[104].

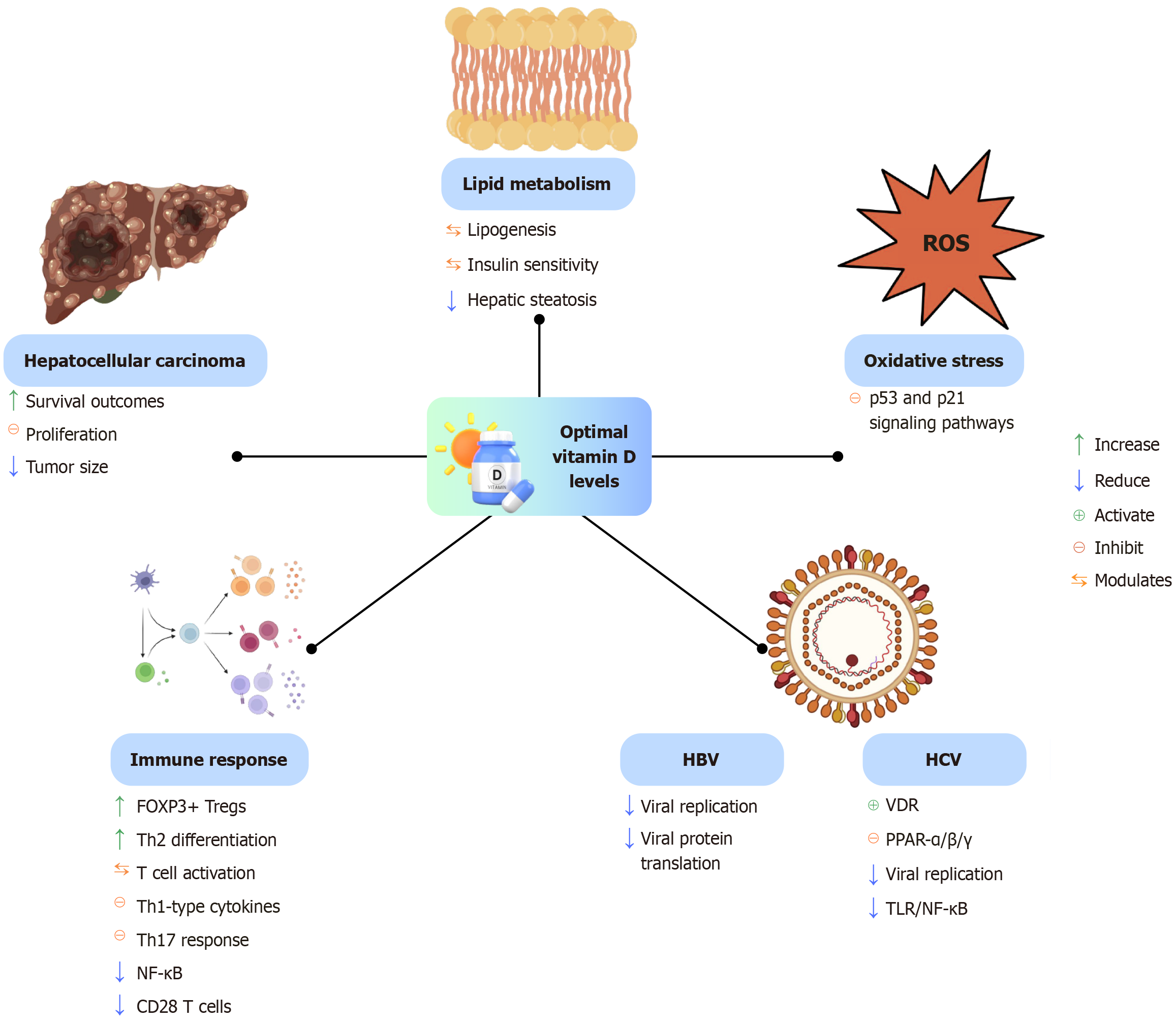

The vitamin D-VDR axis plays a direct role in modulating key metabolic and inflammatory pathways involved in MASLD progression, especially in individuals with overweight or obesity. VDR signaling within hepatocytes influences lipogenesis and bile metabolism, contributing to metabolic homeostasis[104]. In murine models of MASLD, vitamin D supplementation has been shown to reduce hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress, partly through inhibition of the p53-p21 signaling pathway and the suppression of cellular senescence[118].

In the context of chronic caloric excess and weight gain, dysfunction in AT is a key determinant in the development of MASLD in individuals with obesity[119]. Notably, obesity also influences bone health. Epidemiological data from postmenopausal women with obesity show an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures in the humerus and distal lower limbs, but a reduced risk in the hip, pelvis, and wrist. Although data in men are limited, a similar fracture risk pattern has been reported[120]. These fracture risks may be linked to reduced mobility as well as mechanical stress and chronic inflammation, which negatively impact bone metabolism[121-123].

AT dysfunction and accompanying metabolic deterioration are strongly associated with increased intrahepatic fat accumulation, regardless of body mass index or type 2 diabetes status[124-126]. Importantly, AT is a primary target of vitamin D action, where the hormone modulates insulin sensitivity, reduces local inflammation, regulates adipokine secretion, and helps prevent hepatic steatosis[110,113].

Vitamin D supplementation may offer therapeutic benefits for MASLD in both pediatric and adult populations. Several studies have reported positive outcomes, including improvements in liver enzymes and metabolic parameters[127-129]. However, other studies have shown minimal or no clinical benefit under similar conditions[130-132]. Therefore, larger and well-designed clinical trials are needed to clarify the therapeutic value of vitamin D supplementation in MASLD, particularly in patients with documented vitamin D deficiency.

Figure 4 illustrates the multifaceted biological functions of vitamin D when present at optimal levels.

As previously discussed, vitamin D plays a significant anti-inflammatory role in carcinogenesis[133]. Chronic inflammation induces oxidative stress, primarily through the activation of neutrophils and Kupffer cells, thereby promoting tumor development[134].

HCC is the most common primary liver cancer and typically arises in the context of chronic liver disease[135]. The rising global incidence of HCC is strongly associated with chronic HBV and HCV infections[136,137]. Other major risk factors include MASLD[138,139] and exposure to mycotoxins, such as aflatoxins[140,141].

Emerging evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiency (defined as < 20 ng/mL) may increase the risk of developing HCC[142,143] and is also associated with higher mortality rates[144]. In contrast, adequate serum levels of bioavailable 25(OH)D (≥ 30 ng/mL) have been linked to improved survival outcomes in patients with HCC[145].

Regarding supplementation, several in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that vitamin D and its analogs can inhibit the proliferation of liver cancer cell lines and reduce tumor burden in murine models[146-148]. These findings support the potential therapeutic value of vitamin D in the prevention and management of HCC, although further clinical studies are needed to validate these effects in human populations.

Vitamin D deficiency is a common feature in patients with liver cirrhosis, with a reported prevalence ranging from 64% to 92%, significantly higher than in the general population[149,150]. As vitamin D plays an important role in immune regulation, antioxidant defense, and musculoskeletal health, its deficiency has been associated with several complications related to cirrhosis.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is one of the most frequent and serious infections in cirrhotic patients. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent among those with SBP and has been identified as an independent predictor of both infection and mortality[151-153]. As calcidiol [25(OH)D] modulates innate immune responses, low levels may impair bacterial clearance and increase susceptibility to infection.

Several studies have suggested a relationship between vitamin D deficiency and the presence of esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients[154]. Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, the involvement of vitamin D in vascular remodeling, inflammation and portal pressure regulation may contribute to this association. However, further research is needed.

Sarcopenia, defined as the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, is a common and debilitating com

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neuropsychiatric syndrome arising from hepatic insufficiency and portosystemic shunting[156]. Its pathogenesis involves hyperammonemia, astrocyte dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress[156,157]. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with increased HE severity. A cross-sectional study found significantly lower serum calcidiol levels in patients with HE, with negative correlation between vitamin D levels and HE grade[158].

Vitamin D also exhibits antioxidant activity. It enhances the expression of glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase and catalase, and upregulates genes involved in glutathione synthesis such as glutamate-cysteine ligase via VDR signaling[159]. In other neurological contexts, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vitamin D supplementation has been shown to reduce oxidative stress and improve cognitive outcomes[160] suggesting potential benefits in HE as well.

Several studies have consistently reported that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased mortality in patients with cirrhosis[161]. Among older adults, especially women over 70, maintaining sufficient vitamin D levels has been linked to a 6%-11% reduction in overall mortality[162].

However, more recent large-scale clinical trials have failed to show a mortality benefit from vitamin D supplementation in younger or healthier populations, likely due to lower baseline risk[163]. Nonetheless, vitamin D supplementation may still confer survival advantages in more vulnerable groups[164].

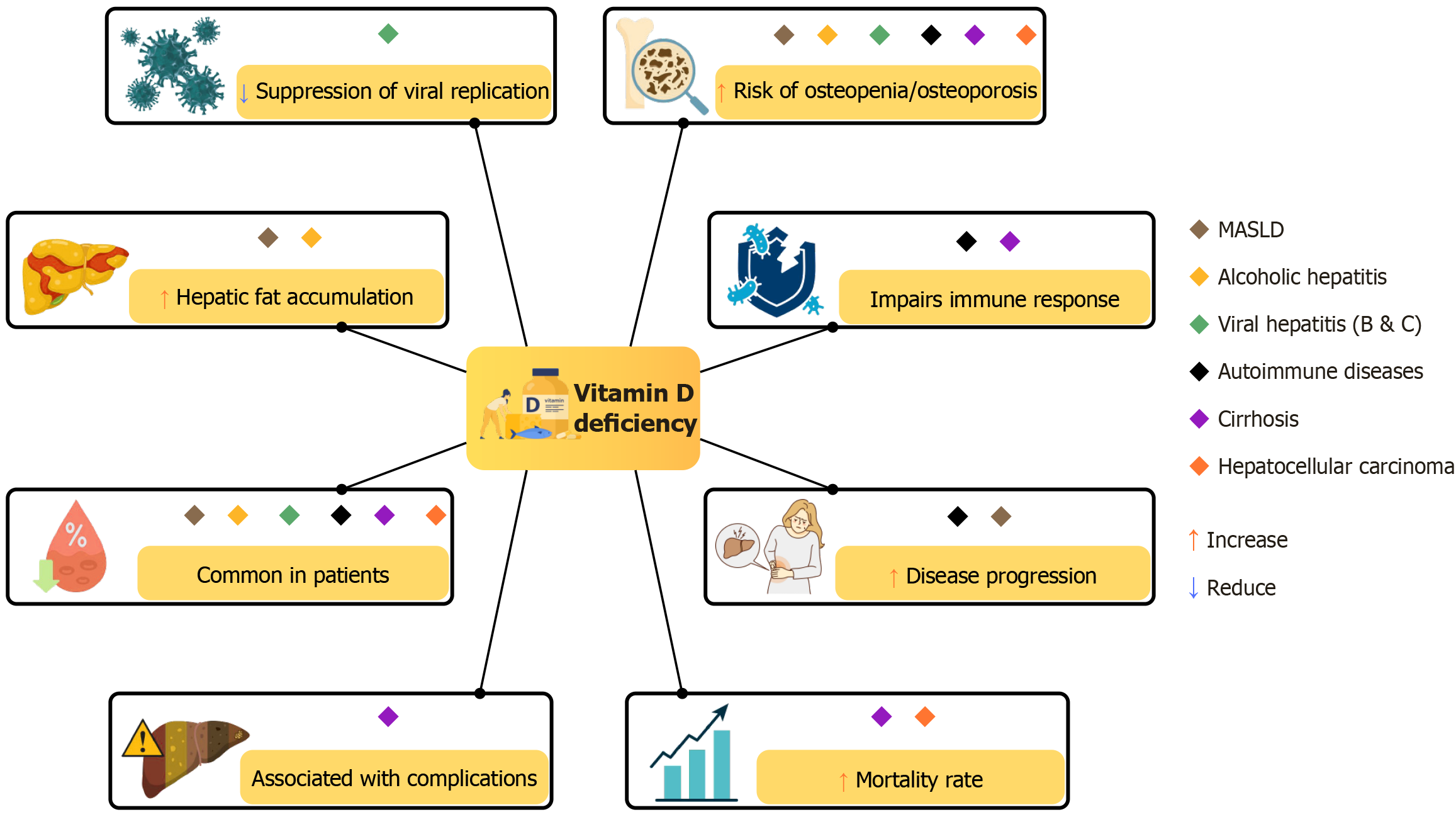

Figure 5 illustrates the clinical consequences of vitamin D deficiency across various liver diseases.

Vitamin D plays an active role in the pathophysiology of chronic liver diseases, influencing immune responses, fibrosis, oxidative stress, and metabolic regulation. Deficiency is common in autoimmune, viral, alcoholic, and metabolic liver conditions and is associated with an increased risk of complications and mortality. Mechanistic evidence supports its regulatory role through VDR signaling, while clinical data suggest an emerging role as a prognostic marker. However, evidence supporting supplementation remains inconsistent. Vitamin D should be recognized as a modifiable factor in liver disease progression, and further research is needed to clarify its therapeutic potential and define effective clinical strategies.

| 1. | Sirajudeen S, Shah I, Al Menhali A. A Narrative Role of Vitamin D and Its Receptor: With Current Evidence on the Gastric Tissues. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, Luderer HF, Lieben L, Mathieu C, Demay M. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:726-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1214] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jäpelt RB, Jakobsen J. Vitamin D in plants: a review of occurrence, analysis, and biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spyksma EE, Alexandridou A, Mai K, Volmer DA, Stokes CS. An Overview of Different Vitamin D Compounds in the Setting of Adiposity. Nutrients. 2024;16:231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bikle D, Christakos S. New aspects of vitamin D metabolism and action - addressing the skin as source and target. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:234-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Valero Zanuy M, Hawkins Carranza F. Metabolismo, fuentes endógenas y exógenas de vitamina D. Rev Esp Enferm Metab Óseas. 2007;16. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alzohily B, AlMenhali A, Gariballa S, Munawar N, Yasin J, Shah I. Unraveling the complex interplay between obesity and vitamin D metabolism. Sci Rep. 2024;14:7583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schuster I. Cytochromes P450 are essential players in the vitamin D signaling system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:186-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jones G, Prosser DE, Kaufmann M. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of vitamin D. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:13-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Heaney RP. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1535-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Delrue C, Speeckaert MM. Vitamin D and Vitamin D-Binding Protein in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:4642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bergwitz C, Jüppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:91-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khundmiri SJ, Murray RD, Lederer E. PTH and Vitamin D. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:561-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Martin A, David V, Quarles LD. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:131-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khazai N, Judd SE, Tangpricha V. Calcium and vitamin D: skeletal and extraskeletal health. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5358-5364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Perwad F, Zhang MY, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Fibroblast growth factor 23 impairs phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism in vivo and suppresses 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase expression in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1577-F1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shimada T, Yamazaki Y, Takahashi M, Hasegawa H, Urakawa I, Oshima T, Ono K, Kakitani M, Tomizuka K, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Vitamin D receptor-independent FGF23 actions in regulating phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F1088-F1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Slominski AT, Kim TK, Li W, Postlethwaite A, Tieu EW, Tang EKY, Tuckey RC. Detection of novel CYP11A1-derived secosteroids in the human epidermis and serum and pig adrenal gland. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Slominski AT, Tuckey RC, Jenkinson C, Li W, Jetten AM. Chapter 6 - Alternative pathways for vitamin D metabolism. In: Hewison FM, Bouillon R, Giovannucci E, Goltzman D, Meyer M, Welsh J, editors. Feldman and Pike' s Vitamin D (Fifth Edition). United States: Academic Press, 2024: 85-109. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Giustina A, Bilezikian JP, Adler RA, Banfi G, Bikle DD, Binkley NC, Bollerslev J, Bouillon R, Brandi ML, Casanueva FF, di Filippo L, Donini LM, Ebeling PR, Fuleihan GE, Fassio A, Frara S, Jones G, Marcocci C, Martineau AR, Minisola S, Napoli N, Procopio M, Rizzoli R, Schafer AL, Sempos CT, Ulivieri FM, Virtanen JK. Consensus Statement on Vitamin D Status Assessment and Supplementation: Whys, Whens, and Hows. Endocr Rev. 2024;45:625-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:582S-586S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Romagnoli E, Pepe J, Piemonte S, Cipriani C, Minisola S. Management of endocrine disease: value and limitations of assessing vitamin D nutritional status and advised levels of vitamin D supplementation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169:R59-R69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bouillon R, Marcocci C, Carmeliet G, Bikle D, White JH, Dawson-Hughes B, Lips P, Munns CF, Lazaretti-Castro M, Giustina A, Bilezikian J. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:1109-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 739] [Article Influence: 105.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zerwekh JE. Blood biomarkers of vitamin D status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1087S-1091S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ferrari D, Lombardi G, Banfi G. Concerning the vitamin D reference range: pre-analytical and analytical variability of vitamin D measurement. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2017;27:030501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, Murad MH, Weaver CM; Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6974] [Cited by in RCA: 7045] [Article Influence: 469.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G, Kovacs CS, Mayne ST, Rosen CJ, Shapses SA. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2655] [Cited by in RCA: 2888] [Article Influence: 192.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hanley DA, Cranney A, Jones G, Whiting SJ, Leslie WD, Cole DE, Atkinson SA, Josse RG, Feldman S, Kline GA, Rosen C; Guidelines Committee of the Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada. Vitamin D in adult health and disease: a review and guideline statement from Osteoporosis Canada. CMAJ. 2010;182:E610-E618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70:172-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 749] [Article Influence: 107.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | American Geriatrics Society Workgroup on Vitamin D Supplementation for Older Adults. Recommendations abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Consensus Statement on vitamin D for Prevention of Falls and Their Consequences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chevalley T, Brandi ML, Cashman KD, Cavalier E, Harvey NC, Maggi S, Cooper C, Al-Daghri N, Bock O, Bruyère O, Rosa MM, Cortet B, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Cherubini A, Dawson-Hughes B, Fielding R, Fuggle N, Halbout P, Kanis JA, Kaufman JM, Lamy O, Laslop A, Yerro MCP, Radermecker R, Thiyagarajan JA, Thomas T, Veronese N, de Wit M, Reginster JY, Rizzoli R. Role of vitamin D supplementation in the management of musculoskeletal diseases: update from an European Society of Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) working group. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34:2603-2623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gascon-Barré M, Demers C, Mirshahi A, Néron S, Zalzal S, Nanci A. The normal liver harbors the vitamin D nuclear receptor in nonparenchymal and biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1034-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 34. | Triantos C, Aggeletopoulou I, Thomopoulos K, Mouzaki A. Vitamin D-Liver Disease Association: Biological Basis and Mechanisms of Action. Hepatology. 2021;74:1065-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tourkochristou E, Mouzaki A, Triantos C. Gene Polymorphisms and Biological Effects of Vitamin D Receptor on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Development and Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:8288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rochel N. Vitamin D and Its Receptor from a Structural Perspective. Nutrients. 2022;14:2847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang H, Shen Z, Lin Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu P, Zeng H, Yu M, Chen X, Ning L, Mao X, Cen L, Yu C, Xu C. Vitamin D receptor targets hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α and mediates protective effects of vitamin D in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:3891-3905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Elangovan H, Stokes RA, Keane J, Chahal S, Samer C, Agoncillo M, Yu J, Chen J, Downes M, Evans RM, Liddle C, Gunton JE. Vitamin D Receptor Regulates Liver Regeneration After Partial Hepatectomy in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2024;165:bqae077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Beilfuss A, Sowa JP, Sydor S, Beste M, Bechmann LP, Schlattjan M, Syn WK, Wedemeyer I, Mathé Z, Jochum C, Gerken G, Gieseler RK, Canbay A. Vitamin D counteracts fibrogenic TGF-β signalling in human hepatic stellate cells both receptor-dependently and independently. Gut. 2015;64:791-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ding N, Yu RT, Subramaniam N, Sherman MH, Wilson C, Rao R, Leblanc M, Coulter S, He M, Scott C, Lau SL, Atkins AR, Barish GD, Gunton JE, Liddle C, Downes M, Evans RM. A vitamin D receptor/SMAD genomic circuit gates hepatic fibrotic response. Cell. 2013;153:601-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Duran A, Hernandez ED, Reina-Campos M, Castilla EA, Subramaniam S, Raghunandan S, Roberts LR, Kisseleva T, Karin M, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. p62/SQSTM1 by Binding to Vitamin D Receptor Inhibits Hepatic Stellate Cell Activity, Fibrosis, and Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:595-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Gong J, Gong H, Liu Y, Tao X, Zhang H. Calcipotriol attenuates liver fibrosis through the inhibition of vitamin D receptor-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway. Bioengineered. 2022;13:2658-2672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dong B, Zhou Y, Wang W, Scott J, Kim K, Sun Z, Guo Q, Lu Y, Gonzales NM, Wu H, Hartig SM, York RB, Yang F, Moore DD. Vitamin D Receptor Activation in Liver Macrophages Ameliorates Hepatic Inflammation, Steatosis, and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Hepatology. 2020;71:1559-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zhou Y, Dong B, Kim KH, Choi S, Sun Z, Wu N, Wu Y, Scott J, Moore DD. Vitamin D Receptor Activation in Liver Macrophages Protects Against Hepatic Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Mice. Hepatology. 2020;71:1453-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | von Essen MR, Kongsbak M, Schjerling P, Olgaard K, Odum N, Geisler C. Vitamin D controls T cell antigen receptor signaling and activation of human T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Berti E, Colonna M, Adorini L. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106:3490-3497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Gorman S, Kuritzky LA, Judge MA, Dixon KM, McGlade JP, Mason RS, Finlay-Jones JJ, Hart PH. Topically applied 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances the suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+ cells in the draining lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2007;179:6273-6283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Boonstra A, Barrat FJ, Crain C, Heath VL, Savelkoul HF, O'Garra A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4974-4980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 877] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Ogura M, Nishida S, Ishizawa M, Sakurai K, Shimizu M, Matsuo S, Amano S, Uno S, Makishima M. Vitamin D3 modulates the expression of bile acid regulatory genes and represses inflammation in bile duct-ligated mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:564-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Gonzalez-Sanchez E, El Mourabit H, Jager M, Clavel M, Moog S, Vaquero J, Ledent T, Cadoret A, Gautheron J, Fouassier L, Wendum D, Chignard N, Housset C. Cholangiopathy aggravation is caused by VDR ablation and alleviated by VDR-independent vitamin D signaling in ABCB4 knockout mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2021;1867:166067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011– . [PubMed] |

| 52. | Hossein-nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:720-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 720] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Bouillon R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:466-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9399] [Cited by in RCA: 9581] [Article Influence: 504.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Hewison M, Bouillon R, Giovannucci E, Goltzman D. Vitamin D. 4th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2018. |

| 56. | Reboul E. Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: from the meal to the enterocyte. Food Funct. 2015;6:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Silva MC, Furlanetto TW. Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2018;76:60-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Mavar M, Sorić T, Bagarić E, Sarić A, Matek Sarić M. The Power of Vitamin D: Is the Future in Precision Nutrition through Personalized Supplementation Plans? Nutrients. 2024;16:1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Rizzoli R. Vitamin D supplementation: upper limit for safety revisited? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Urashima M, Segawa T, Okazaki M, Kurihara M, Wada Y, Ida H. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Fassio A, Adami G, Rossini M, Giollo A, Caimmi C, Bixio R, Viapiana O, Milleri S, Gatti M, Gatti D. Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cholecalciferol in Healthy Subjects with Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized Open-Label Study. Nutrients. 2020;12:1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ravaioli F, Pivetti A, Di Marco L, Chrysanthi C, Frassanito G, Pambianco M, Sicuro C, Gualandi N, Guasconi T, Pecchini M, Colecchia A. Role of Vitamin D in Liver Disease and Complications of Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:9016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Harvey NC, Ward KA, Agnusdei D, Binkley N, Biver E, Campusano C, Cavalier E, Clark P, Diaz-Curiel M, Fuleihan GE, Khashayar P, Lane NE, Messina OD, Mithal A, Rizzoli R, Sempos C, Dawson-Hughes B; International Osteoporosis Foundation Vitamin D Working Group. Optimisation of vitamin D status in global populations. Osteoporos Int. 2024;35:1313-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Yoshiji H, Nagoshi S, Akahane T, Asaoka Y, Ueno Y, Ogawa K, Kawaguchi T, Kurosaki M, Sakaida I, Shimizu M, Taniai M, Terai S, Nishikawa H, Hiasa Y, Hidaka H, Miwa H, Chayama K, Enomoto N, Shimosegawa T, Takehara T, Koike K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Liver Cirrhosis 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:593-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Stokes CS, Volmer DA, Grünhage F, Lammert F. Vitamin D in chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2013;33:338-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Singal AK, Wong RJ, Dasarathy S, Abdelmalek MF, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Limketkai BN, Petrey J, McClain CJ. ACG Clinical Guideline: Malnutrition and Nutritional Recommendations in Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:950-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Krinsky DL, Ferreri SP, Hemstreet BA, Hume AL, Rollins CJ, Tietze KJ. Handbook of nonprescription drugs: An interactive approach to self-care. 20th ed. Washington DC: American Pharmacists Association, 2020. |

| 68. | Wakeman M. A Literature Review of the Potential Impact of Medication on Vitamin D Status. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:3357-3381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 69. | Agmon-Levin N, Theodor E, Segal RM, Shoenfeld Y. Vitamin D in systemic and organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:256-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sgambato D, Gimigliano F, De Musis C, Moretti A, Toro G, Ferrante E, Miranda A, De Mauro D, Romano L, Iolascon G, Romano M. Bone alterations in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:1908-1925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Czaja AJ, Montano-Loza AJ. Evolving Role of Vitamin D in Immune-Mediated Disease and Its Implications in Autoimmune Hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:324-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Sergi CM. Vitamin D supplementation for autoimmune hepatitis: A need for further investigation. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Efe C, Kav T, Aydin C, Cengiz M, Imga NN, Purnak T, Smyk DS, Torgutalp M, Turhan T, Ozenirler S, Ozaslan E, Bogdanos DP. Low serum vitamin D levels are associated with severe histological features and poor response to therapy in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:3035-3042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1009] [Article Influence: 112.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 75. | Ebadi M, Ip S, Lytvyak E, Asghari S, Rider E, Mason A, Montano-Loza AJ. Vitamin D Is Associated with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Nutrients. 2022;14:878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Wang Z, Peng C, Wang P, Sui J, Wang Y, Sun G, Liu M. Serum vitamin D level is related to disease progression in primary biliary cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:1333-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Guichelaar MM, Malinchoc M, Sibonga JD, Clarke BL, Hay JE. Bone histomorphometric changes after liver transplantation for chronic cholestatic liver disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2190-2199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Parés A, Guañabens N. Osteoporosis in primary biliary cirrhosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:407-24; x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Guañabens N, Cerdá D, Monegal A, Pons F, Caballería L, Peris P, Parés A. Low bone mass and severity of cholestasis affect fracture risk in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2348-2356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 80. | Ebadi M, Bhanji RA, Mazurak VC, Lytvyak E, Mason A, Czaja AJ, Montano-Loza AJ. Severe vitamin D deficiency is a prognostic biomarker in autoimmune hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Shibamoto A, Kaji K, Nishimura N, Kubo T, Iwai S, Tomooka F, Suzuki J, Tsuji Y, Fujinaga Y, Kawaratani H, Namisaki T, Akahane T, Yoshiji H. Vitamin D deficiency exacerbates alcohol-related liver injury via gut barrier disruption and hepatic overload of endotoxin. J Nutr Biochem. 2023;122:109450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Xu H, Wu Z, Feng F, Li Y, Zhang S. Low vitamin D concentrations and BMI are causal factors for primary biliary cholangitis: A mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1055953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Kempinska-Podhorodecka A, Milkiewicz M, Wasik U, Ligocka J, Zawadzki M, Krawczyk M, Milkiewicz P. Decreased Expression of Vitamin D Receptor Affects an Immune Response in Primary Biliary Cholangitis via the VDR-miRNA155-SOCS1 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Nakchbandi IA, van der Merwe SW. Current understanding of osteoporosis associated with liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:660-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Liaskou E, Jeffery LE, Trivedi PJ, Reynolds GM, Suresh S, Bruns T, Adams DH, Sansom DM, Hirschfield GM. Loss of CD28 expression by liver-infiltrating T cells contributes to pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:221-232.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Seitz HK, Bataller R, Cortez-Pinto H, Gao B, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Mueller S, Szabo G, Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 891] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Chaudhry H, Sohal A, Iqbal H, Roytman M. Alcohol-related hepatitis: A review article. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2551-2570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 88. | Savić Ž, Vračarić V, Milić N, Nićiforović D, Damjanov D, Pellicano R, Medić-Stojanoska M, Abenavoli L. Vitamin D supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective study. Minerva Med. 2018;109:352-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Soares JB, Pimentel-Nunes P, Roncon-Albuquerque R, Leite-Moreira A. The role of lipopolysaccharide/toll-like receptor 4 signaling in chronic liver diseases. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:659-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Wang H, Gong W, Gao J, Cheng W, Hu Y, Hu C. Effects of vitamin D deficiency on chronic alcoholic liver injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;224:220-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Hoan NX, Tong HV, Song LH, Meyer CG, Velavan TP. Vitamin D deficiency and hepatitis viruses-associated liver diseases: A literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:445-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | González-Calvin JL, Mundi JL, Casado-Caballero FJ, Abadia AC, Martin-Ibañez JJ. Bone mineral density and serum levels of soluble tumor necrosis factors, estradiol, and osteoprotegerin in postmenopausal women with cirrhosis after viral hepatitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4844-4850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Hoan NX, Khuyen N, Binh MT, Giang DP, Van Tong H, Hoan PQ, Trung NT, Anh DT, Toan NL, Meyer CG, Kremsner PG, Velavan TP, Song LH. Association of vitamin D deficiency with hepatitis B virus - related liver diseases. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Wang CC, Tzeng IS, Su WC, Li CH, Lin HH, Yang CC, Kao JH. The association of vitamin D with hepatitis B virus replication: Bystander rather than offender. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:1634-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Chen EQ, Bai L, Zhou TY, Fe M, Zhang DM, Tang H. Sustained suppression of viral replication in improving vitamin D serum concentrations in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Mohamadkhani A, Bastani F, Khorrami S, Ghanbari R, Eghtesad S, Sharafkhah M, Montazeri G, Poustchi H. Negative Association of Plasma Levels of Vitamin D and miR-378 With Viral Load in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. Hepat Mon. 2015;15:e28315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Gal-Tanamy M, Bachmetov L, Ravid A, Koren R, Erman A, Tur-Kaspa R, Zemel R. Vitamin D: an innate antiviral agent suppressing hepatitis C virus in human hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2011;54:1570-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 99. | Matsumura T, Kato T, Sugiyama N, Tasaka-Fujita M, Murayama A, Masaki T, Wakita T, Imawari M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses hepatitis C virus production. Hepatology. 2012;56:1231-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 100. | Lange CM, Bojunga J, Ramos-Lopez E, von Wagner M, Hassler A, Vermehren J, Herrmann E, Badenhoop K, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Vitamin D deficiency and a CYP27B1-1260 promoter polymorphism are associated with chronic hepatitis C and poor response to interferon-alfa based therapy. J Hepatol. 2011;54:887-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Petta S, Cammà C, Scazzone C, Tripodo C, Di Marco V, Bono A, Cabibi D, Licata G, Porcasi R, Marchesini G, Craxí A. Low vitamin D serum level is related to severe fibrosis and low responsiveness to interferon-based therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1158-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 102. | Lương Kv, Nguyễn LT. Theoretical basis of a beneficial role for vitamin D in viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5338-5350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Sriphoosanaphan S, Thanapirom K, Kerr SJ, Suksawatamnuay S, Thaimai P, Sittisomwong S, Sonsiri K, Srisoonthorn N, Teeratorn N, Tanpowpong N, Chaopathomkul B, Treeprasertsuk S, Poovorawan Y, Komolmit P. Effect of vitamin D supplementation in patients with chronic hepatitis C after direct-acting antiviral treatment: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Aggeletopoulou I, Tsounis EP, Triantos C. Vitamin D and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): Novel Mechanistic Insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:4901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, Thorelius L, Holmqvist M, Bodemar G, Kechagias S. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44:865-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1647] [Cited by in RCA: 1734] [Article Influence: 86.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Nexus of Metabolic and Hepatic Diseases. Cell Metab. 2018;27:22-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 69.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 3280] [Article Influence: 328.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 108. | Abbas MA. Physiological functions of Vitamin D in adipose tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;165:369-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Elseweidy MM, Amin RS, Atteia HH, Ali MA. Vitamin D3 intake as regulator of insulin degrading enzyme and insulin receptor phosphorylation in diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;85:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Marziou A, Philouze C, Couturier C, Astier J, Obert P, Landrier JF, Riva C. Vitamin D Supplementation Improves Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Reduces Hepatic Steatosis in Obese C57BL/6J Mice. Nutrients. 2020;12:342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Udomsinprasert W, Jittikoon J. Vitamin D and liver fibrosis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1351-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Wang M, Wang M, Zhang R, Shen C, Zhang L, Ding Y, Tang Z, Wang H, Zhang W, Chen Y, Wang J. Influences of Vitamin D Levels and Vitamin D-Binding Protein Polymorphisms on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Risk in a Chinese Population. Ann Nutr Metab. 2022;78:61-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Barchetta I, Cimini FA, Cavallo MG. Vitamin D and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): An Update. Nutrients. 2020;12:3302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Barchetta I, Carotti S, Labbadia G, Gentilucci UV, Muda AO, Angelico F, Silecchia G, Leonetti F, Fraioli A, Picardi A, Morini S, Cavallo MG. Liver vitamin D receptor, CYP2R1, and CYP27A1 expression: relationship with liver histology and vitamin D3 levels in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2012;56:2180-2187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 115. | Chung GE, Kim D, Kwak MS, Yang JI, Yim JY, Lim SH, Itani M. The serum vitamin D level is inversely correlated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Liu T, Xu L, Chen FH, Zhou YB. Association of serum vitamin D level and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32:140-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Wang X, Li W, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Qin G. Association between vitamin D and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: results from a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:17221-17234. [PubMed] |

| 118. | Ma M, Long Q, Chen F, Zhang T, Wang W. Active vitamin D impedes the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting cell senescence in a rat model. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:513-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |