Published online Jan 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i1.100392

Revised: November 29, 2024

Accepted: December 17, 2024

Published online: January 27, 2025

Processing time: 143 Days and 23.3 Hours

Liver function of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients is essentially normal after treatment with antiviral drugs. In rare cases, persistently abnormally elevated α-fetoprotein (AFP) is seen in CHB patients following long-term antiviral treatment. However, in the absence of imaging evidence of liver cancer, a reasonable expla

To explore the causes of abnormal AFP in patients with CHB who were not diag

From November 2019 to May 2023, 15 patients with CHB after antiviral treatment and elevated AFP were selected. Clinical data and quality indicators related to laboratory testing, imaging data, and pathological data were obtained through inpatient medical records.

All patients had increased AFP and significantly elevated IgG. Cancer was excluded by imaging examination. Only four patients had elevated alanine ami

For patients with CHB and elevated AFP after antiviral treatment, autoimmune hepatitis should be considered. CHB with AIH is clinically insidious and difficult to detect, and prone to progression to cirrhosis. Liver puncture pathological examination should be performed when necessary to confirm diagnosis.

Core Tip: There is no reasonable explanation for the continuous abnormal increase of α-fetoprotein (AFP) in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) after long-term antiviral therapy and the lack of imaging evidence of liver tumor. We observed 15 patients with CHB treated with antiviral therapy without imaging evidence of liver cancer, and explored the cause of elevated AFP by liver biopsy. Pathological examination suggested that autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) might be complicated, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed by a comprehensive and a simplified diagnostic scoring system for AIH.

- Citation: Jiang ML, Xu F, Li JL, Luo JY, Hu JL, Zeng XQ. Clinical features of abnormal α-fetoprotein in 15 patients with chronic viral hepatitis B after treatment with antiviral drugs. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(1): 100392

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i1/100392.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i1.100392

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is the largest public health burden in China. Long-term treatment with antiviral drugs inhibits HBV DNA replication and controls liver inflammation in most CHB patients. The indexes reflecting liver damage, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and α-fetoprotein (AFP) decrease and return to normal levels[1]. However, in rare cases, a sustained abnormal increase in AFP is detected in patients with CHB following long-term antiviral treatment, while there is a lack of imaging evidence of liver tumors, and thus no reasonable expla

We enrolled 15 CHB patients with elevated AFP who underwent liver biopsy at the Fifth People's Hospital of Ganzhou City between November 2019 and May 2023. CHB is defined as positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for > 6 months[2]. Patients received antiviral therapy with oral nucleoside analogs. Exclusion criteria were: history of excessive alcohol consumption (defined as ≥ 20 g/d for men and ≥ 10 g/d for women, or 2 weeks of heavy drinking ≥ 80 g/d); drug-induced hepatitis; schistosomiasis liver disease; liver cancer; Human immunodeficiency virus infection or hepatitis A, C, or D; pregnancy; as well as patients receiving corticosteroids, chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy, liver transplantation, or hemodialysis. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fifth People's Hospital of Ganzhou City.

The following clinical data were collected: Age; sex; antiviral treatment; and results of routine blood tests and serological examination. Liver function indicators were collected before hormone therapy, and 1 and 2-3 months after treatment, including total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin (ALB), ALT, AST, total bile acid (TBA), γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), AFP, other viral hepatitis markers, autoantibodies (antinuclear antibody), and IgG. Imaging, such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, was performed.

A comprehensive diagnostic scoring system (1999)[3] and a simplified diagnostic scoring system (2008)[4] were used to diagnose autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

All assessments were carried out by specialists who had extensive experience in ultrasound diagnosis. A 16G puncture needle (Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc., Tempe, AZ, United States) was used for percutaneous liver biopsy. The length of the obtained tissue exceeded 1.5 cm. After fixation with formalin, the tissue underwent standard procedures including dehydration, paraffin embedding, sectioning, as well as routine hematoxylin and eosin, Masson, and reticular fiber staining. Subsequently, two liver pathologists evaluated the tissue based on the Ishak Histological Scoring System.

Measurement data conforming to normal distribution were presented by mean and standard deviation. Comparison between the two groups was performed by Student's t-test. If the distribution did not conform to normal, the Mann-Whi

We enrolled 15 patients diagnosed with CHB, 10 men and five women, with an average age of 54 years (range 48-69 years). Four patients showed elevated ALT levels, 10 elevated AST, nine elevated TBIL, six elevated ALP, and 10 elevated GGT. All patients underwent antiviral treatment prior to liver biopsy, and eight achieved a complete HBV response (HBV-DNA < 10 U/L), five had HBV-DNA levels < 2 × 103 U/L, and two had HBV-DNA levels > 2 × 103 U/L. Seven patients with CHB received initial antiviral therapy (≤ 6 months), including five with entecavir, one with tenofovir, and one with tenofovir amibufenamide. Eight patients received long-term antiviral therapy (≥ 6 months), including seven who were managed with entecavir and one with tenofovir alafenamide fumarate. Two patients ANA positive (1:320 and 1:160) and 13 were autoantibody negative (Table 1).

| No. | Sex | Age | ALT | AST | TBIL | ALP | GGT | TBA | ALB | AFP | ANA | IgG | HBV-DNA |

| 1 | Female | 62 | 29.9 | 41.3 | 8.9 | 98.9 | 281.7 | 24.5 | 41.4 | 29.77 | 1: 320 | 18.73 | 30.8 |

| 2 | Male | 48 | 61.9 | 100.3 | 27 | 114.4 | 57.5 | 82.6 | 27.9 | 32.96 | - | 30 | -1 |

| 3 | Male | 56 | 35.7 | 44 | 58.6 | 140.9 | 106.8 | 78.3 | 27.9 | 19.36 | - | 25.1 | -1 |

| 4 | Female | 64 | 77 | 69.7 | 24.3 | 143.7 | 100.1 | 67.9 | 25.9 | 142.96 | - | 34.7 | 6.49 × 103 |

| 5 | Male | 57 | 34.5 | 50.3 | 46.5 | 92 | 93.3 | 299.5 | 29.8 | 85.75 | - | 26 | -1 |

| 6 | Female | 57 | 28.5 | 65 | 44.5 | 149.9 | 185.8 | 45.6 | 25 | 77.42 | 1: 160 | 21.15 | 1.27 × 102 |

| 7 | Male | 67 | 15.5 | 21.8 | 18.8 | 71.8 | 48 | 34.8 | 34 | 8.47 | <1: 80 | 21.8 | -1 |

| 8 | Male | 57 | 22.7 | 57.2 | 20.1 | 107.7 | 46.2 | 39.7 | 33 | 42.99 | <1: 80 | 28.03 | 5.48 × 102 |

| 9 | Male | 60 | 34.3 | 66 | 45.8 | 157.8 | 92 | 60.9 | 24.1 | 18.56 | - | 22.32 | -1 |

| 10 | Female | 69 | 20.6 | 27 | 12.6 | 178.5 | 41 | 2 | 22.3 | 14.28 | <1: 80 | 25.23 | -1 |

| 11 | Female | 51 | 39.5 | 35 | 17.2 | 73.1 | 51 | 33.5 | 40.3 | 6.85 | <1: 80 | 20.27 | 3.06 × 102 |

| 12 | Male | 49 | 24.7 | 30 | 33.1 | 111.1 | 134 | 3.8 | 28.8 | 340.1 | <1: 80 | 19.89 | 51.5 |

| 13 | Male | 52 | 36.4 | 104 | 50.5 | 148.8 | 179 | 12.5 | 36.9 | 1004 | <1: 80 | 24.48 | 5.24 × 103 |

| 14 | Male | 57 | 72.6 | 63 | 8.1 | 59.1 | 48 | 70.8 | 40.5 | 158.3 | <1: 80 | 22.04 | -1 |

| 15 | Male | 50 | 24 | 32 | 30.3 | 123.7 | 65 | 8 | 35.1 | 10.69 | <1: 80 | 25.27 | -1 |

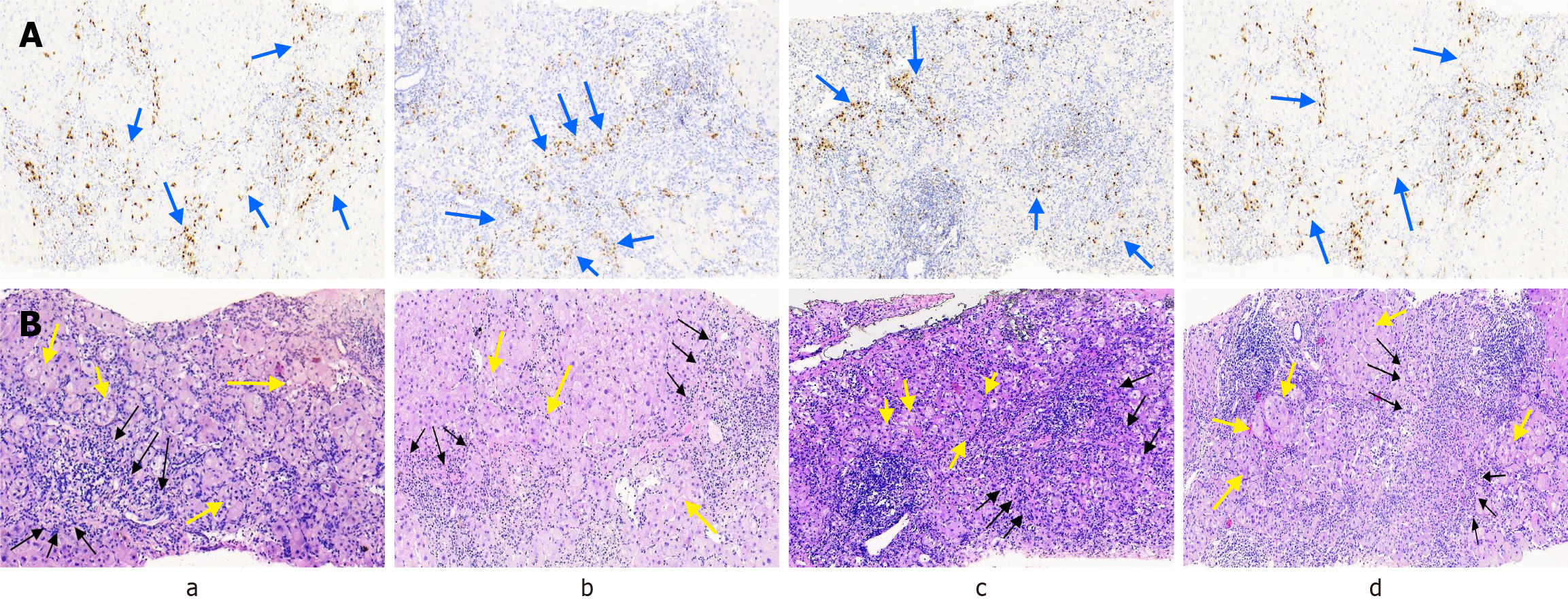

The pathological alterations of the liver were primarily attributed to necrotizing inflammation around the portal area or the surrounding septal region. All patients demonstrated predominant liver cell injury attributed to interfacial hepatitis. Fourteen patients presented with severe interfacial necrotizing inflammation along with lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltration. Fusion necrosis was observed in 14 patients, with 13 experiencing severe fusion necrosis (≥ 4 points). A typical rosette (florid duct lesion; FDL) was observed in 14 patients. All 15 patients exhibited pathological manifestations of lobulitis and portal inflammation, with 11 demonstrating grade 3/4 lobulitis and 13 showing grade 3/4 portal inflammation. None of the 15 patients had bile duct disappearance but four had bile duct injury and nine had cholestasis (Figure 1). The mean Ishak histological score was 14.38. According to the histopathological diagnosis of AIH, the liver puncture pathological morphology in 14 patients was consistent with that of AIH, while one patient exhibited atypical findings. Intrahepatic inflammation was graded at G3 and above in 14 (93.33%) patients. Fourteen patients had intrahepatic fibrosis grade above S3 (Table 2).

| No. | II | Lym/PCs I | FN | BN | FDL | LI | PI | BDI | ABD | Fibrosis | Ishak score | G | S |

| 1 | 3 | Yes | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | G3 | S1 |

| 2 | 3 | Yes | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 | G3-4 | S4 |

| 3 | 4 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 | G3-4 | S4 |

| 4 | 4 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 17 | G3-4 | S3-4 |

| 5 | 4 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16 | G2-3 | S4 |

| 6 | 4 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 18 | G4 | S3-4 |

| 7 | 4 | No | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 | G2-3 | S4 |

| 8 | 4 | Yes | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17 | G4 | S4 |

| 9 | 4 | Yes | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 15 | G3-4 | S4 |

| 10 | 3 | Yes | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 15 | G3-4 | S3-4 |

| 11 | 3 | Yes | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 17 | G3 | S4 |

| 12 | 4 | Yes | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 16 | G4 | S4 |

| 13 | 4 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17 | G3 | S3-4 |

| 14 | 3 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | G3 | S3-4 |

| 15 | 2 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | G2 | S3-4 |

AIH diagnostic scores were calculated for all 15 patients using both the AIH simplified diagnostic score system and the integrated diagnostic score system. In their respective scoring systems, two patients were classified as probable AIH using the simplified diagnostic score system, while four were classified as probable AIH using the integrated diagnostic score system. None of the patients were diagnosed as “clear” with either diagnostic scoring system (Table 3). The speci

| No. | Integrated diagnostic score | Simplified diagnostic score | |

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | ||

| 1 | 13 | 15 | 6 |

| 2 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 3 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 4 | 12 | 14 | 4 |

| 5 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 6 | 10 | 12 | 6 |

| 7 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 8 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 9 | 8 | 10 | 4 |

| 10 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 11 | 10 | 12 | 4 |

| 12 | 8 | 10 | 4 |

| 13 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 14 | 8 | 10 | 4 |

| 15 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

After undergoing liver biopsy for the consideration of AIH diagnosis, 14 patients received treatment with immunosuppressants (prednisone 20-40 mg/d alone or 50 mg/d in combination with azathioprine). After 8-12 week, all patients showed improvement in symptoms. There was a significant decrease in AFP and IgG levels (Table 4), as well as de

| Parameters | Pre-hormone therapy | 1 months after hormone therapy | 2-3 months after hormone therapy | Z/t | P value |

| AFP (μg/L) | 32.96 (12.49-114.36) | 15.38 (11.21-41.71) | 5.2 (3.94, 9.44)1 | 3.18 | 0.001 |

| Parameters | Pre-hormone therapy | 2-3 months after hormone therapy | Z/t | P value |

| IgG | 24.83 ± 4.32 | 16.09 ± 2.87 | 16.263 | < 0.001 |

| ALT | 41 (33.85-255.5) | 34.7 (28.5-39.5) | 1.153 | 0.249 |

| AST | 51 (39-221) | 33 (27.5-43) | 2.274 | 0.023 |

| TBIL | 24.3 (14.9-45.5) | 18.5 (13.15-46.25) | 0.454 | 0.65 |

| ALP | 115.58 ± 35.99 | 82.72 ± 28.13 | 4.035 | 0.002 |

| GGT | 100.26 ± 72.99 | 63.22 ± 24.96 | 1.591 | 0.138 |

| TBA | 39.7 (18.5-74.55) | 49.2 (12.95-90.15) | 0.874 | 0.382 |

| ALB | 32.31 ± 6.36 | 36.18 ± 4.57 | 2.983 | 0.011 |

AFP is a glycoprotein that is synthesized by the liver and found in fetal serum. Abnormal elevation of AFP is often associated with liver injury. Liver injury can result in the activation and proliferation of liver precursor cells, leading to an increase in AFP secretion. Elevated levels of human AFP are significantly linked to germ cell tumors, such as yolk sac tumors[5] and testicular cancer[6]. Additionally, increased AFP is commonly observed in pregnant women. In several studies involving patients with liver cancer, it was found that AFP levels were significantly elevated. Subsequent research has demonstrated that AFP is a highly specific and sensitive marker for hepatocellular carcinoma[7]. A significant number of patients with acute and chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis without malignancy have elevated serum AFP levels, which subsequently decrease after the recovery of liver inflammation. Therefore, an elevated level of AFP is closely associated with liver injury, indicating increased DNA synthesis or the regeneration of liver cells.

In this study, all 15 patients received antiviral therapy, and imaging examination ruled out the possibility of a tumor, but AFP levels remained abnormal. Some reports suggest that the incidence of abnormally elevated serum AFP levels in patients with active viral hepatitis is significantly reduced after the initiation of antiviral therapy[1,8,9]. Qian et al[10] conducted a study on 3680 patients with non-HCC viral hepatitis from five central hospitals and found that antiviral treatment was associated with a decrease in AFP levels (2.68 ng/mL). Therefore, the 15 patients in our study had a decreased likelihood of elevated APF and active viral hepatitis. AFP levels may be elevated in patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, although it is typically a transient phenomenon[11,12]. In this study, 11 patients were found to have advanced liver fibrosis. However, the increased AFP levels persisted for several weeks, and the correlation between increased AFP and advanced liver fibrosis was deemed insufficient. During the examination of autoantibodies, a persistent increase in IgG levels was observed. Antiviral therapy led to a decrease in transaminase and viral load in 15 patients, but serum AFP, transaminases, and IgG levels were fully normalized only after immunosuppressive therapy. These findings are consistent with the study results of Efe et al[13]. In patients with active HBV combined with AIH, antiviral therapy alone could not completely restore ALT, AST, and IgG levels to normal; therefore, combined immuno

The clinical diagnosis of AIH relies on the AIH comprehensive and simplified diagnostic scoring systems, with liver pathological features serving as key evidence. Both CHB and AIH are chronic inflammatory lesions mainly caused by liver cell injury[14]. The pathological features of CHB are characterized mainly by necrotizing and lobular inflammation in the portal vein area, which is nonspecific and challenging to differentiate from other chronic liver injuries. The primary histological characteristics of AIH include interface hepatitis, infiltration of lymphocytes/plasma cells, and FDL. Com

Patients with CHB combined with AIH exhibited more severe histological inflammation than in patients with either condition alone, often accompanied by active inflammation. Previous studies conducted abroad have indicated that hepatitis virus infection may lead to autoimmune liver disease and exacerbate its progression. Additionally, there is a higher likelihood of advanced liver fibrosis[16]. In another study of 139 cases of autoimmune liver disease, the liver pathology results showed that the proportion of patients with hepatitis virus infection and liver fibrosis stage F3/F4 was significantly higher than that of patients with pure autoimmune liver disease[17]. This suggests that the degree of liver inflammation in patients with CHB combined with AIH is often more severe than that in patients with single AIH or CHB. However, the proportion of patients with AIH and advanced liver fibrosis in Sbikina et al’s study was significantly lower than that in our study (93.33%), as the study encompassed HBsAg-negative patients with previous HBV infection[17]. There is a continuous inflammatory response to liver cells and liver cell necrosis, which leads to an increase in AFP production, promotes the immunoregulatory function of the body, and enhances the repair and regeneration ability of liver cells. According to a study by Ma Xiong et al[18] in China, it was found that 94.12% of patients with CHB combined with AIH had liver inflammatory activity above G3. This further indicates that patients with CHB combined with AIH exhibit relatively active liver inflammatory activity.

One drawback of this study was the small sample size. In addition, the follow-up time was short, and the effect of long-term immunotherapy on anti-HBV therapy in CHB patients with AIH was not observed. The number of AIH patients with CHB combined with increased AFP was not counted in this study, and the incidence of AIH in CHB combined with increased AFP was poorly understood. Therefore, further multicenter studies with sufficiently large sample sizes and long follow-up periods are needed to detect significant associations between the results.

This is the first case series to demonstrate an association between AFP and CHB with AIH. AIH based on CHB is prone to being overlooked. This study offers a novel diagnostic proposal for CHB with AIH. After treating CHB patients with persistently abnormal AFP and excluding tumor-related disorders, it is essential to contemplate the possibility of CHB combined with AIH and other types of chronic active hepatitis. If necessary, liver biopsy can be used to aid in diagnosis.

| 1. | Shim JJ, Kim JW, Lee CK, Jang JY, Kim BH. Oral antiviral therapy improves the diagnostic accuracy of alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1699-1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | You H, Wang F, Li T, Xu X, Sun Y, Nan Y, Wang G, Hou J, Duan Z, Wei L, Jia J, Zhuang H; Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B (version 2022). J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11:1425-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, Donaldson PT, Eddleston AL, Fainboim L, Heathcote J, Homberg JC, Hoofnagle JH, Kakumu S, Krawitt EL, Mackay IR, MacSween RN, Maddrey WC, Manns MP, McFarlane IG, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Zeniya M. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 2017] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, Bianchi FB, Shibata M, Schramm C, Eisenmann de Torres B, Galle PR, McFarlane I, Dienes HP, Lohse AW; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1307] [Article Influence: 72.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Guo YL, Zhang YL, Zhu JQ. Prognostic value of serum α-fetoprotein in ovarian yolk sac tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patel P, Balise R, Srinivas S. Variations in normal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in patients with testicular cancer on surveillance. Onkologie. 2012;35:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kelly SL, Bird TG. The Evolution of the Use of Serum Alpha-fetoprotein in Clinical Liver Cancer Surveillance. J Immunobiol. 2016;1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Nishimura T, Muraoka M, Suzuki Y, Tamaki N, Yasui Y, Hosokawa T, Ueda K, Nakanishi H, Itakura J, Takahashi Y, Kurosaki M, Enomoto N, Nakagawa M, Kakinuma S, Watanabe M, Izumi N. α-fetoprotein levels after interferon therapy and risk of hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2013;58:1253-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen TM, Huang PT, Tsai MH, Lin LF, Liu CC, Ho KS, Siauw CP, Chao PL, Tung JN. Predictors of alpha-fetoprotein elevation in patients with chronic hepatitis C, but not hepatocellular carcinoma, and its normalization after pegylated interferon alfa 2a-ribavirin combination therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:669-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qian X, Liu Y, Wu F, Zhang S, Gong J, Nan Y, Hu B, Chen J, Zhao J, Chen X, Pan W, Dang S, Lu F. The Performance of Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein for Detecting Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Influenced by Antiviral Therapy and Serum Aspartate Aminotransferase: A Study in a Large Cohort of Hepatitis B Virus-Infected Patients. Viruses. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Atiq O, Tiro J, Yopp AC, Muffler A, Marrero JA, Parikh ND, Murphy C, McCallister K, Singal AG. An assessment of benefits and harms of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2017;65:1196-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Qian X, Liu S, Long H, Zhang S, Yan X, Yao M, Zhou J, Gong J, Wang J, Wen X, Zhou T, Zhai X, Xu Q, Zhang T, Chen X, Hu G, Wang J, Gao Z, Nan Y, Chen J, Hu B, Zhao J, Lu F. Reappraisal of the diagnostic value of alpha-fetoprotein for surveillance of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:20-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Efe C, Wahlin S, Ozaslan E, Purnak T, Muratori L, Quarneti C, Tatar G, Simsek H, Muratori P, Schiano TD. Diagnostic difficulties, therapeutic strategies, and performance of scoring systems in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and concurrent hepatitis B/C. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 607] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Rubio CA, Truskaite K, Rajani R, Kaufeldt A, Lindström ML. A method to assess the distribution and frequency of plasma cells and plasma cell precursors in autoimmune hepatitis. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:665-669. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Batskikh S, Morozov S, Vinnitskaya E, Sbikina E, Borunova Z, Dorofeev A, Sandler Y, Saliev K, Kostyushev D, Brezgin S, Kostyusheva A, Chulanov V. May Previous Hepatitis B Virus Infection Be Involved in Etiology and Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Liver Diseases? Adv Ther. 2022;39:430-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sbikina ES, Vinnitskaya EV, Batskikh SN, Sandler YG, Saliev KG, Khaimenova TY, Bordin DS. [Assessment of the possible impact of hepatitis viruses on the development and course of autoimmune liver diseases]. Ter Arkh. 2023;95:173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/