Published online May 27, 2024. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v16.i5.843

Revised: February 6, 2024

Accepted: April 15, 2024

Published online: May 27, 2024

Processing time: 190 Days and 0.4 Hours

Occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) is a globally prevalent infection, with its frequency being influenced by the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in a particular geographic region, including Africa. OBI can be transmitted th

To highlight the genetic diversity and prevalence of OBI in Africa.

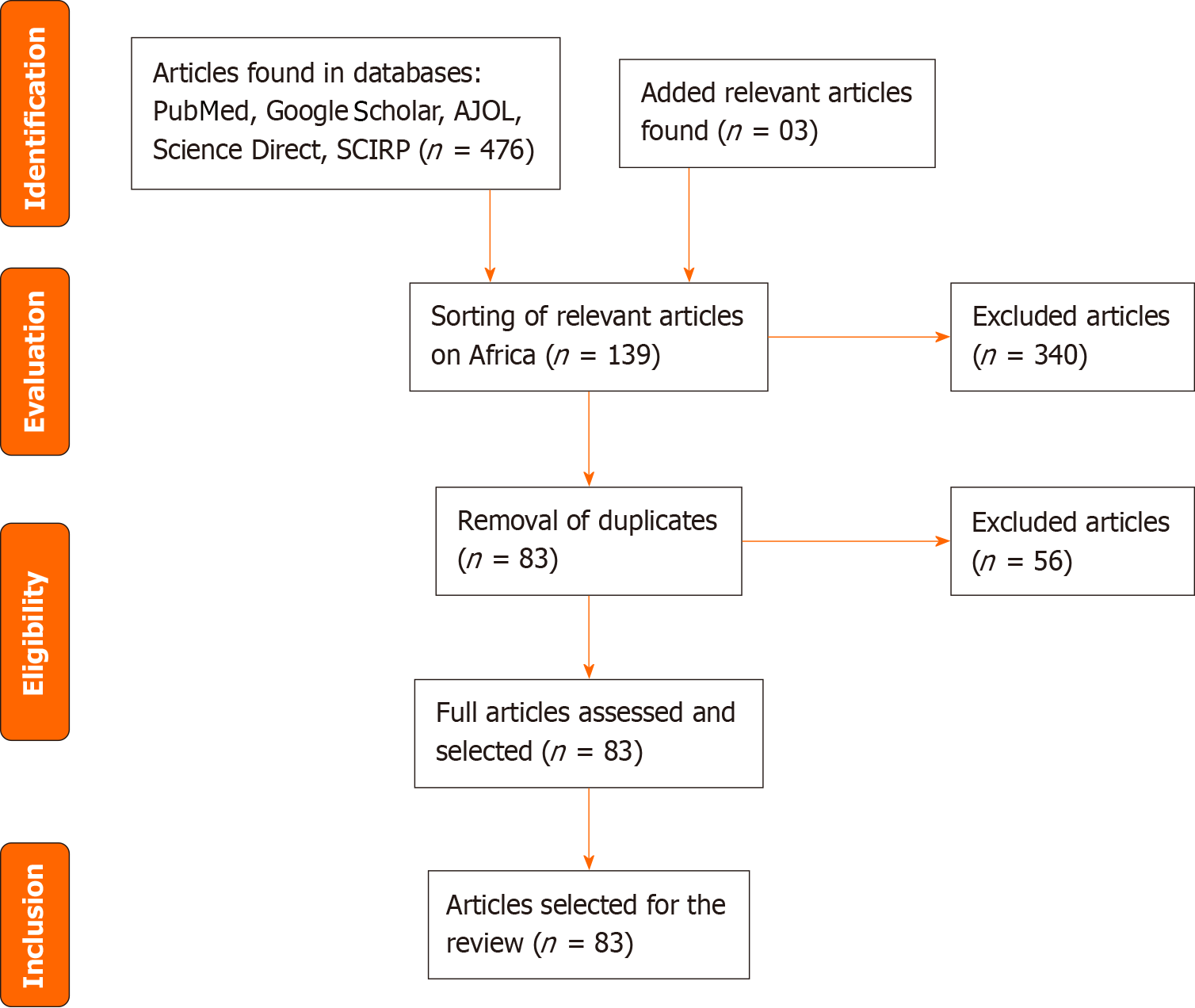

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and involved a comprehensive search on PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and African Journals Online for published studies on the prevalence and genetic diversity of OBI in Africa.

The synthesis included 83 articles, revealing that the prevalence of OBI varied between countries and population groups, with the highest prevalence being 90.9% in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and 38% in blood donors, indicating an increased risk of HBV transmission through blood transfusions. Cases of OBI reactivation have been reported following chemotherapy. Genotype D is the predominant, followed by genotypes A and E.

This review highlights the prevalence of OBI in Africa, which varies across countries and population groups. The study also demonstrates that genotype D is the most prevalent.

Core Tip: The objective of this systematic literature review is to highlight the genetic diversity and prevalence of occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) in Africa. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and involved a comprehensive search on PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and African Journals Online for published studies on the prevalence and genetic diversity of OBI in Africa. This review highlights the prevalence of OBI in Africa, which varies across countries and population groups. The study also demonstrates that genotype D is the most prevalent.

- Citation: Bazie MM, Sanou M, Djigma FW, Compaore TR, Obiri-Yeboah D, Kabamba B, Nagalo BM, Simpore J, Ouédraogo R. Genetic diversity and occult hepatitis B infection in Africa: A comprehensive review. World J Hepatol 2024; 16(5): 843-859

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v16/i5/843.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v16.i5.843

Occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) refers to the presence of replicating hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA [cDNA (cccDNA)] in the liver or in the blood of individuals who test negative for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) on available tests[1] and when the viral load is detectable, it is generally lower than 200 (IU)/mL[2]. OBI is present worldwide, but is more fre

OBI can be classified based on HBV-specific antibody profiles and HBV DNA levels[12,13]. In seropositive OBI, anti-hepatitis B antibody (anti-HBc) and/or hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) are positive; in seronegative OBI, both anti-HBc antibody and anti-HBs antibody are negative. There are cases of OBI that have HBV DNA levels similar to those usually detected in the different phases of overt HBV infection[12].

Most cases of OBI are related to a replication-competent virus whose replication and transcription activities are str

The prevalence of OBI varies widely and may be attributed to population heterogeneity, viral DNA detection tech

This comprehensive review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[18,19]. We searched the literature for scientific articles on OBI. In February 2022, an electronic literature search was conducted and the following databases were used: PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, African Journal Oline. A second update search was conducted in February 2023 to look for additional articles. The investigations were conducted in French and English with the following keywords: “occult hepatitis B infection” or “occult hepatitis B.” The filters were “free complete items” on “human” blood samples. The inclusion criterion was open-access articles or worked on the population of an African country. All study groups were included. The study groups concerned were: Blood donors, patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), patients infected with HCV, patients with HCC, hem

A total of 476 articles were found in the databases, with an addition of 03 articles from the manual search. After excluding irrelevant articles (340) and removing duplicates (56), 83 articles were examined. Following a thorough evaluation of the full text, all 83 articles were deemed relevant and included in this synthesis.

Geographical distribution of OBI in Africa has been extensively studied in various population groups across several countries. These studies have reported varying prevalence rates of OBI, ranging from 0 to 90.9%, depending on the country and the population studied[20,21]. The prevalence of OBI is influenced by several factors, including the prevalence of HBV infection, the sensitivity of diagnostic tests, and the population studied. In countries where HBV infection is highly endemic, the prevalence of OBI tends to be higher. This is the case in Burkina Faso where the prevalence of HBV is between 9.1% to 14.4%[22,23] and the prevalence of occult HBV infection is between 4% and 32.8%[24,25] in blood donors, and 7.3% in the general population[26]. In Gambia, the prevalence of occult HBV infection is 18.3% in the general population[27]. A prevalence of 18.7% of OBI was found in a Kenyan population at high risk of HBV infection[28]; Among health care workers, who are a high-risk group for infection, respective OBI prevalences of 5.3% and 6.7% have been demonstrated in Egypt and South Africa[29,30]. However, the presence of OBI has also been reported in countries where HBV infection is less common[3,31]. This is the example of Egypt, where the prevalence of HBV is around 1.4%[32] while the prevalence of OBI ranges from 0 to 90.7%[20,21]. Research has shown that the prevalence of OBI is not uniform across different regions of Africa. For instance, studies conducted in West Africa have reported relatively higher prevalence rates compared to those in East and Southern Africa. In addition, the prevalence of OBI has been found to vary among different population groups within the same country or region. In febrile patients in Sudan and Tanzania, respective OBI prevalences of 7.7% and 18.2% have been demonstrated[33,34]. Tables 1-5 summarizes the prevalence of OBI in different African countries, highlighting the wide variation in prevalence rates.

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Peliganga et al[47] | 2021 | Angola | Blood donors | 2.9 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 500 | |

| Mbangiwa et al[67] | 2018 | Botswana | Pregnant women with/without HIV | 6.6 | Prospective study | COBAS AmpliPrep | ND | 622 | D3, A1, E |

| Ryan et al[72] | 2017 | Botswana | HIV patient | 26.5 | ND | COBAS AmpliPrep | ND | 272 | |

| Mabunda et al[51] | 2020 | Mozambique | Blood donors | 0.98 | Cross-sectional | PCR | 20 UI/mL | 1435 | |

| Carimo et al[69] | 2018 | Mozambique | ART naïve HIV patient | 8.3 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 206 | |

| Sondlane et al[30] | 2016 | South Africa | Healthcare workers | 6.7 | Descriptive study | Real-time PCR | ND | 314 | |

| Amponsah-Dacosta et al[119] | 2015 | South Africa | Post-vaccination | 66 and 70.4 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 62 and 139 | |

| Powell et al[81] | 2015 | South Africa | HIV patient | 13.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | 250 copies/mL | 394 | |

| Hoffmann et al[65] | 2014 | South Africa | Pregnant women with HIV | 1.71 | Case-control study | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/ mL | 175 | |

| Ayuk et al[82] | 2013 | South Africa | HIV/HBV Co-infection | 33.7 | Unmatched study | Nested PCR | ND | 181 | |

| Bell et al[68] | 2012 | South Africa | ART naive HIV | 3.79 | Cohort | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/ mL | 79 | |

| Mayaphi et al[83] | 2012 | South Africa | HIV/HBV Co-infection HIV patient | 3.5 in AIDS 1 in no AIDS | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 200/200 | |

| Firnhaber et al[66] | 2009 | South Africa | HIV patient | 88.4 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 53 |

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Amer et al[106] | 2020 | Egypt | Haemodialysis patients with HCV | 33.8 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 325 | |

| Abdel-Maksoud et al[104] | 2019 | Egypt | Haemodialysis | 7.3 | Cohort | Nested PCR | 30 copies/mL | 150 | |

| Elmaghloub et al[29] | 2017 | Egypt | Healthcare workers | 5.3 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 132 | |

| Omar et al[93] | 2017 | Egypt | HCV patients with/without schistosomiasis | With schistosomias 12.8% without schistosomias 8.5% | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 200 | |

| Esmail et al[40] | 2016 | Egypt | Haemodialysis without HCV | 8.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 144 | B, C, D |

| Mahmoud et al[87] | 2016 | Egypt | HCV patients | 18 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 100 | |

| Elbedewy et al[114] | 2015 | Egypt | Patient with malignant tumors of the lymphatic system | 13.89 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 12 IU/mL | 72 | |

| Elsawaf et al[21] | 2015 | Egypt | ART in chronic hepatitis C patients | 90.9 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 11 | |

| Helaly et al[108] | 2015 | Egypt | Haemodialysis | 32 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 100 | |

| Kishk et al[58] | 2015 | Egypt | Blood donors | 22.7 | ND | Real-time PCR | 100 copies/mL | 343 | D |

| Mandour et al[109] | 2015 | Egypt | HCV and Haemodialysis | 8.5% in CHC and 1.8% in HD | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 210 et 165 | |

| Raouf et al[92] | 2015 | Egypt | HCV positive cancer children | 32 | case–control study | Nested PCR | ND | 50 | |

| Elrashidy et al[20] | 2014 | Egypt | Diabetic children and adolescents following hepatitis B vaccination | 0 | ND | Nested PCR | 100 copies/mL | 170 | |

| Kishk et al[88] | 2014 | Egypt | CHC patient | 7.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 162 | D |

| El-Ghitany et al[86] | 2013 | Egypt | Blood donors with hepatitis C | 4.16 (3.2 HVC+ et 5.1 HCV-) | case–control study | Real Time PCR | 45 copies/mL | 504 | |

| Elkady et al[113] | 2013 | Egypt | Hematological malignant patients | 5.66 | ND | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/mL | 18 | D1 |

| Said et al[48] | 2013 | Egypt | Blood donors | 1.64 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 3.8 IU/mL | 3167 | |

| Taha et al[42] | 2013 | Egypt | HCV patients with/without hepatocellular carcinoma | 22.5 (17.5 with CHC 5 without CHC) | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 40 | D, B, C, A |

| Youssef et al[36] | 2013 | Egypt | Children with acute HBV | 29.16 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 24 | D (D1, D2) |

| Abu El Makarem et al[105] | 2012 | Egypt | Haemodialysis with/without HCV | 4.1 | ND | Real-time PCR | 6 IU/mL | 145 | |

| Elgohry et al[107] | 2012 | Egypt | Haemodialysis | 26.8 | ND | PCR | ND | 93 | |

| Shaker et al[116] | 2012 | Egypt | Thalassemic children | 32.5 | Prospective study | Real Time PCR | ND | 80 | |

| Hassan et al[41] | 2011 | Egypt | Hepatocellular carcinoma patient | 22.5 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 40 | D, B, A, C |

| Selim et al[89] | 2011 | Egypt | HCV patients | 38.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | 45 copies/mL | 60 | |

| Antar et al[59] | 2010 | Egypt | Blood donors | 0.48 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 1021 | |

| Emara et al[90] | 2010 | Egypt | HCV patients | 3.9 | Cross-sectional | Real-Time PCR | 12 IU/mL | 155 | |

| El-Sherif et al[91] | 2009 | Egypt | HCV patients | 16 | ND | Real-Time PCR | 30 copies/mL | 100 | |

| Said et al [118] | 2009 | Egypt | Children with malignant hematological disorders | 21 | case–control study | Nested PCR | ND | 100 | |

| Youssef et al[43] | 2009 | Egypt | Patient with elevated transaminases | 64.8 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 119 | C (C2), D (D1) |

| El-Zayadi et al[49] | 2008 | Egypt | Blood donors | 1.26 | ND | PCR | ND | 712 | |

| El-Sherif et al[50] | 2007 | Egypt | Blood donors | 1.3 | ND | PCR | ND | 150 |

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Kengne et al[6] | 2021 | Cameroun | Blood donors | 9.83 | Cross-sectional et prospective | PCR | ND | 193 | |

| Fopa et al[57] | 2019 | Cameroun | Blood donors | 2.3 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 1162 | |

| Gachara et al[73] | 2017 | Cameroun | HIV patient | 5.9 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 337 | |

| Bivigou-Mboumba et al[75] | 2018 | Gabon | HIV patient | 17.5 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 50 IU/mL | 137 | |

| Bivigou-Mboumba et al[76] | 2016 | Gabon | HIV patient | 8 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 100 IU/mL | 762 | A E |

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Gissa et al[99] | 2022 | Ethiopia | Patients with chronic liver disease of unidentified cause | 5.56 | Prospective | Real-Time PCR | 15 IU/mL | 36 | |

| Ayana et al[74] | 2020 | Ethiopia | HIV negative/positive isolated antiHBc | 5.6 | ND | Real-Time PCR | ND | 306 | |

| Meier-Stephenson et al[38] | 2020 | Ethiopia | Pregnant women | 20.3 | Prospective | Nested PCR | ND | 182 | D, C |

| Patel et al[44] | 2020 | Ethiopia | HIV patient | 19.1 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 291 | D, E, A, C |

| Salyani et al[70] | 2021 | Kenya | HIV patient ART naïve | 5.3 | Cross-sectional | COBAS AmpliPrep | 20 UI/mL | 208 | |

| Aluora et al[37] | 2020 | Kenya | Blood donors | 2.3 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 300 | A |

| Jepkemei et al[28] | 2020 | Kenya | Populations with high risk of HBV infection | 18.7 | Cohort | Real-time PCR | ND | 99 | |

| Rusine et al[80] | 2013 | Rwanda | HIV patient | 42.9 | Prospective study | PCR | ND | 218 | |

| Ahmed et al[112] | 2022 | Sudan | Patients with chronic renal failure | 22 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | ND | 188 | |

| Mustafa et al[101] | 2020 | Sudan | Renal Transplant Patients | 51.4 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 100 | A, D, E |

| Bashir and Hassan[33] | 2019 | Sudan | Febrile malaria Patients | 18.2 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 88 | |

| Sahr Hagmohamed et al[111] | 2019 | Sudan | Haemodialysis | 15.9 | Cross-sectional | PCR | ND | 88 | |

| Majed et al[100] | 2018 | Sudan | Haemodialysis | 0 | Cross-sectional | PCR | ND | 88 | |

| Hassan et al[55] | 2017 | Sudan | Blood donors | 7.9 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 177 | |

| Mohammed et al[110] | 2015 | Sudan | Haemodialysis | 3.3 | ND | PCR | ND | 91 | |

| Mudawi et al[84] | 2014 | Sudan | HIV patient | 11,07 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 316 | |

| Yousif et al[39] | 2014 | Sudan | HIV patient | 55.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 18 | D, E, A, D/E |

| Abd El Kader Mahmoud et al[46] | 2013 | Sudan | Blood donors | 38 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 100 | |

| Mahgoub et al[56] | 2011 | Sudan | Blood donors | 4.6 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 129 | |

| Meschi et al[34] | 2010 | Tanzania | Febrile patient | 7.7 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 13 |

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Ky/Ba et al[25] | 2021 | Burkina Faso | Blood donors | 4 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | ND | 300 | |

| Diarra et al[26] | 2018 | Burkina Faso | General population | 7.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 219 | E and A3 |

| Somda et al[24] | 2016 | Burkina Faso | Blood donors | 32.8 | Prospective study | Real-time PCR | ND | 160 | |

| Ndow et al[27] | 2022 | Gambia | General population | 18.3 | Case-control study | Nested PCR | 5 IU/mL | 82 | |

| Gouas et al[97] | 2012 | Gambia | Patient with Cirrhosis and HCC | 15% cirrhosis et 24% with HCC | Case–control study | PCR | ND | 34 et 88 | E, D, A |

| Attiku et al[77] | 2021 | Ghana | HIV/HBV co-infected patients | 30.8 | Longitudinal purposive study | Real-time PCR | 2 copies/mL | 13 | |

| Attia et al[78] | 2012 | Ivory Coast | HIV patient | 21.3 | Cross-sectional | COBAS Amplicor HBV | 6 UI/mL | 188 | |

| Fasola et al[60] | 2021 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 1 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 1 IU/mL | 100 | |

| Akintule et al[52] | 2018 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 8.7 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 206 | 83.3% A 11.1% no A |

| Olotu et al[53] | 2016 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 5.4 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/mL | 354 | |

| Oluyinka et al[61] | 2015 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 17 | ND | Real-time PCR | ND | 492 | |

| Nna et al[54] | 2014 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 8 | ND | Nested PCR | ND | 100 | |

| Opaleye et al[79] | 2014 | Nigeria | HIV patient | 11.8 | ND | PCR | ND | 188 |

OBI is known to be caused by HBV, which has ten genotypes (A-J)[35]. However, only five of these genotypes have been identified as causing OBI, namely genotypes A, B, C, D, and E (Table 6). Studies conducted in Africa have highlighted that the three most commonly found genotypes in this region are genotypes A, D, and E[11,35,36].

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Mbangiwa et al[67] | 2018 | Botswana | Pregnant women with/without HIV | 6.6 | Prospective study | COBAS AmpliPrep | 622 | D3, A1, E |

| Diarra et al[26] | 2018 | Burkina Faso | General population | 7.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | 219 | E and A3 |

| Esmail et al[40] | 2016 | Egypt | Haemodialysis without HCV | 8.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | 144 | B, C, D |

| Kishk et al[58] | 2015 | Egypt | Blood donors | 22.7 | ND | Real-time PCR | 343 | D |

| Kishk et al[88] | 2014 | Egypt | CHC patient | 7.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | 162 | D |

| Elkady et al[113] | 2013 | Egypt | Hematological malignant patients | 5.66 | ND | Real-time PCR | 18 | D1 |

| Taha et al[42] | 2013 | Egypt | HCV patients with/without hepatocellular carcinoma | 22.5 (17.5 with CHC 5 without CHC) | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 40 | D, B, C, A |

| Youssef et al[36] | 2013 | Egypt | Children with acute HBV | 29,16 | ND | Real-time PCR | 24 | D (D1, D2) |

| Hassan et al[41] | 2011 | Egypt | Hepatocellular carcinoma patient | 22.5 | ND | Nested PCR | 40 | D, B, A, C |

| Youssef et al[43] | 2009 | Egypt | Patient with elevated transaminases | 64.8 | ND | Nested PCR | 119 | C (C2), D (D1) |

| Meier-Stephenson et al[38] | 2020 | Ethiopia | Pregnant women | 20.3 | Prospective | Nested PCR | 182 | D, C |

| Patel et al[44] | 2020 | Ethiopia | HIV patient | 19.1 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 291 | D, E, A, C |

| Bivigou-Mboumba et al[76] | 2016 | Gabon | HIV patient | 8 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 762 | A, E |

| Gouas et al[97] | 2012 | Gambia | Patient with Cirrhosis and HCC | 15% cirrhosis et 24% with HCC | case–control study | PCR | 34 et 88 | E, D, A |

| Aluora et al[37] | 2020 | Kenya | Blood donors | 2.3 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 300 | A |

| Akintule et al[52] | 2018 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 8.7 | ND | Nested PCR | 206 | 83.3% A 11.1% no A |

| Ibrahim et al[102] | 2020 | Sudan | Renal transplant patients | 18 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 100 | D, A, E |

| Mustafa et al[101] | 2020 | Sudan | Renal Transplant Patients | 51,4 | ND | Real-time PCR | 100 | A, D, E |

| Yousif et al[39] | 2014 | Sudan | HIV patient | 55.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | 18 | D, E, A, D/E |

Genotype D has been identified as the most predominant genotype in Africa, followed by genotypes A and E[37-39]. This information is summarized in Table 6. In contrast, genotypes B and C were initially identified in other regions of the world, such as Asia, Australia, Greenland, and Canada[35]. However, they have been found in Africa as well, specifically in Egypt[40-43] and Ethiopia[44]. The geographic distribution of HBV genotypes is associated with distinct modes of HBV transmission. For instance, genotypes B and C are prevalent in highly endemic areas, where perinatal or mother-to-child transmission plays an important role in the spread of HBV[45].

Table 7 summarizes the different methods used and their detection limits. In the majority of studies, real-time PCR was used compared to nested PCR.

| Ref. | Year | Countries | Patients | OBI prevalence, n (%) | Types of studies | Methods | DNA low limit of detection | Effective | HBV genotype |

| Abdel-Maksoud et al[104] | 2019 | Egypt | Haemodialysis | 7.3 | Cohort | Nested PCR | 30 copies/mL | 150 | |

| Elbedewy et al[114] | 2015 | Egypt | Patient with malignant tumors of the lymphatic system | 13.89 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 12 IU/mL | 72 | |

| Kishk et al[58] | 2015 | Egypt | Blood donors | 22.7 | ND | Real-time PCR | 100 copies/mL | 343 | D |

| Elrashidy et al[20] | 2014 | Egypt | Diabetic children and adolescents following hepatitis B vaccination | 0 | ND | Nested PCR | 100 copies/mL | 170 | |

| El-Ghitany et al[86] | 2013 | Egypt | Blood donors with hepatitis C | 4,16 (3,2 HVC+ et 5,1 HCV-) | Case–control study | Real time PCR | 45 copies/mL | 504 | |

| Elkady et al[113] | 2013 | Egypt | Hematological malignant patients | 5.66 | ND | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/mL | 18 | D1 |

| Said et al[48] | 2013 | Egypt | Blood donors | 1.64 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 3.8 IU/mL | 3167 | |

| Abu El Makarem et al[105] | 2012 | Egypt | Haemodialysis with/without HCV | 4.1 | ND | Real-time PCR | 6 IU/mL | 145 | |

| Selim et al[89] | 2011 | Egypt | HCV patients | 38.3 | ND | Real-time PCR | 45 copies/mL | 60 | |

| Emara et al[90] | 2010 | Egypt | HCV patients | 3.9 | Cross-sectional | Real-Time PCR | 12 IU/mL | 155 | |

| El-Sherif et al[91] | 2009 | Egypt | HCV patients | 16 | ND | Real-Time PCR | 30 copies/mL | 100 | |

| Gissa et al[99] | 2022 | Ethiopia | Patients with chronic liver disease of unidentified cause | 5.56 | Prospective | Real-Time PCR | 15 IU/mL | 36 | |

| Bivigou-Mboumba et al[75] | 2018 | Gabon | HIV patient | 17.5 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 50 IU/mL | 137 | |

| Bivigou-Mboumba et al[76] | 2016 | Gabon | HIV patient | 8 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 100 IU/mL | 762 | A E |

| Ndow et al[27] | 2022 | Gambia | General population | 18.3 | Case-control study | Nested PCR | 5 IU/mL | 82 | |

| Attiku et al[77] | 2021 | Ghana | HIV/HBV co-infected patients | 30.8 | Longitudinal purposive study | Real-time PCR | 2 copies/mL | 13 | |

| Attia et al[78] | 2012 | Ivory Coast | HIV patient | 21.3 | Cross-sectional | COBAS Amplicor HBV | 6 UI/mL | 188 | |

| Salyani et al[70] | 2021 | Kenya | HIV patient ART naïve | 5.3 | Cross-sectional | COBAS AmpliPrep | 20 UI/mL | 208 | |

| Mabunda et al[51] | 2020 | Mozambique | Blood donors | 0.98 | Cross-sectional | PCR | 20 UI/mL | 1435 | |

| Fasola et al[60] | 2021 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 1 | Cross-sectional | Nested PCR | 1 IU/mL | 100 | |

| Olotu et al[53] | 2016 | Nigeria | Blood donors | 5.4 | Cross-sectional | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/mL | 354 | |

| Powell et al[81] | 2015 | South Africa | HIV patient | 13.5 | ND | Real-time PCR | 250 copies/mL | 394 | |

| Hoffmann et al[65] | 2014 | South Africa | Pregnant women with HIV | 1.71 | Case-control study | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/ mL | 175 | |

| Bell et al[68] | 2012 | South Africa | ART naive HIV | 3.79 | Cohort | Real-time PCR | 20 IU/ mL | 79 |

The high prevalence of OBI among blood donors in African countries poses a significant risk of HBV transmission during blood transfusions. The prevalence of OBI in blood donors ranges from 0.48% to 38% (Tables 1-5). The prevalence is particularly high in Sudan (38%)[46] and Burkina Faso (32.8%)[24]. In other African countries[37,47-56], the prevalence ranges from 0.48% to 22.7%, with Nigeria having a prevalence of 1% to 17%[6,57-61]. These high prevalences are a cause for concern, as blood transfusion is a major risk factor for HBV transmission, especially in countries that screen potential blood donors using minimal methods[62]. In contrast, the prevalence of OBI among blood donors in China, South Korea, and Japan is relatively low, ranging from 0.016% to 1.01%[63,64]. The prevalence of OBI in blood donors in these countries is significantly lower than that in African countries. The relatively low prevalence of OBI in blood donors in these countries may be due to the use of more sensitive diagnostic tests and the implementation of strict screening measures to detect and exclude donors with OBI.

However, even in countries where screening measures are in place, a residual risk of HBV transmission associated with donors with occult B infection and deficient levels of viral DNA that are undetectable or detected intermittently by the most sensitive unitary viral genome tests persists[5]. This residual risk of transmission has been reported in several African countries, including Ghana[7], Burkina Faso[8] and Cameroon[6] with percentages ranging from 0.24% to 11.16%.

Co-infection with both HBV and HIV is common, as these viruses share common routes of transmission. In HIV-positive patients, the prevalence of OBI ranges from 1.71% to 88.4%, with South Africa having the highest prevalence[65,66]. Among pregnant women living with HIV, prevalences are 1.71% in South Africa[65] and 6.6% in Botswana[67]. Among HIV patients starting antiretroviral therapy (ART), prevalences are 3.7% in South Africa[68], 26.5% in 8.3% in Moza

OBI is frequently found in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC)[85]. A range of prevalence rates from 3.2% to 90.9%[21,86] and all studies found were conducted in Egypt[87-91] (Table 2). A low prevalence of 3.2% was found in blood donors[86], whereas the highest prevalence of 90.9% was found in patients undergoing antiviral therapy for hepatitis C[21]. Children with cancer had a prevalence rate of 32% for OBI, according to a study by Raouf et al[92]. Additionally, a study by Omar et al[93] reported a prevalence of 12.8% in OBI/HCV patients with schistosomiasis, compared to 8.5% in those without schistosomiasis. The prevalence of OBI was higher in Egyptian hepatitis C patients with HCC at 17.5% than in those without the condition at 5%[42]. Since HBV and HCV share the same transmission routes and many risk factors, OBI detection in HCV patients is not unexpected[94].

HCC is the most common form of liver cancer[95] and HBV infection is the most significant risk factor for its development, accounting for approximately 33% of cases[96]. The prevalence of OBI in HCC patients varies from 17.5% to 24% (Tables 2 and 5). Studies conducted by Hassan et al[41] in Egypt, and Gouas et al[97] in Gambia, have shown a high prevalence of OBI in HCC patients. In CHC patients with HCC, OBI prevalences are around 17.5% compared to 5% in those who do not have HCC[42]. Studies conducted in Asia and Europe have also reported high prevalences of OBI in chronic HCV patients with HCC compared to those without HCC, ranging from 15% to 49% vs 73%, respectively[9,98]. The detection of OBI in HCC patients is critical for early diagnosis and treatment of HCC.

A prevalence of 5.56% of OBI was found in patients with chronic liver disease of unidentified cause[99].

The prevalence of OBI in haemodialysis patients ranges from 0% to 51.4%, as reported in studies conducted in Egypt and Sudan[100,101] (Tables 2 and 4). Renal transplant patients have also shown a high prevalence of OBI, ranging from 18% to 51.4%, according to studies conducted by Ibrahim et al[102] and Mustafa et al[101] in Sudan. Haemodialysis patients are at a higher risk of HBV transmission due to frequent blood transfusions[103], making the detection of OBI in these patients a critical concern. Non-negligible prevalences of occult hepatitis B infection in hemodialysis patients with or without hepatitis C have been found in certain studies[104-112].

Reactivation of OBI has been demonstrated in Egypt by Elkady et al[113] and Elbedewy et al[114] in patients following chemotherapy. In Elkady's study, Five HBsAg-negative and Anti-HBC-positive patients demonstrated HBV reactivation criteria, with two patients becoming serologically positive for HBsAg and three becoming detectable for HBV DNA[113]. Elbedewy’s study showed that of the 10 OBI patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, five patients demonstrated reactivation with positive HBsAg after 7 to 11 months since the start of chemotherapy (all cycles)[114]. The chemotherapy used in this study was Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxyadriamycine, Oncovin and Prednisone). A case of occult hepatitis B reactivation was reported in a homozygous sickle cell patient in Senegal by Diop et al[115].

Thalassemia patients require frequent blood transfusions, which increase their risk of contracting HBV and developing OBI. However, few studies in Africa have assessed the prevalence of OBI in thalassemia patients. In Egypt, a study found a prevalence of 32.5% of OBI in thalassemia children, highlighting the importance of screening for OBI in this population[116]. These high prevalences may be attributed to residual risks of HBV transmission through blood transfusions, which, although infrequent, are not negligible according to several authors[8,62,117].

An OBI prevalence of 21% was found in Egyptian children and adolescents with hematological disorders and mali

The hepatitis B vaccine has been demonstrated to be highly effective in preventing HBV infection and reducing the prevalence of OBI. A study conducted in Egypt on diabetic children and adolescents followed after vaccination found no cases of OBI[20]. Similarly, in South Africa, the introduction of vaccination led to a decrease in the prevalence of OBI. OBI prevalence’s were 70.4% in the study population before vaccine introduction and 66.0% in the study population after vaccine introduction, indicating that the vaccine may play a role in reducing the prevalence of OBI in high-risk populations[119]. It is important to note that the hepatitis B vaccine does not protect against OBI in individuals who have already been exposed to the virus. Therefore, screening for OBI and early detection of infection are crucial in preventing the development of liver disease in high-risk populations.

This comprehensive review provides valuable insights into the prevalence of OBI in high-risk populations, including patients with CHC, haemodialysis patients, patients with HCC, and thalassemia patients.

Studies have shown that patients with CHC are at a high risk of developing OBI, with reported prevalence rates ranging from 3.2% to 90.9%[42,86,92,93]. However, the wide range of reported prevalence rates may be attributed to differences in study design, patient population, and diagnostic methods used. Patients with CHC who have OBI face a greater risk of liver cirrhosis, HCC, and reactivation of HBV infection during immunosuppressive therapy.

Furthermore, haemodialysis and thalassemia patients are also at a high risk of developing OBI due to the frequent blood transfusions required. Prevalence rates of OBI in these patient populations range from 2.2% to 90.9% and 13.6% to 32.5%, respectively[8,62,116,120]. A study showed a similar prevalence of 31.4% among thalassemia patients who had received multiple blood transfusions in India[120].

The high prevalence rates of OBI in these populations may be attributed to the residual risks of HBV transmission through blood transfusions. To minimize this risk, strategies such as HBV nucleic acid testing and vaccination of patients and healthcare workers must be implemented in African countries.

This study suggests a risk of OBI reactivation in patients undergoing chemotherapy and suffering from sickle cell disease[113-115]. HBV reactivation is most commonly reported in patients with lymphoma, but it is unclear whether lymphoma itself increases the risk of HBV reactivation because there are no studies comparing the risk in patients with other diseases receiving similar chemotherapeutic regimens. The frequent association between lymphoma and HBV reactivation might be related to the intensity of the chemotherapy regimen, resulting in marked immunosuppression[121]. Thus, identifying and monitoring OBI in these patient populations is crucial to prevent the risk of reactivation. Because current therapies do not eliminate cccDNA, which serves as a model for HBV replication, thus preventing the eradication of the virus[122,123]. Lymphoid cells that present as a sanctuary can archive cccDNA[124,125].

Our research underscores the importance of hepatitis B vaccination in preventing OBI. For example, a study conducted on diabetic children and adolescents in Egypt found no instances of OBI after vaccination, demonstrating the vaccine's effectiveness in preventing OBI[20]. Similarly, the introduction of vaccination in South Africa[119] led to a reduction in the prevalence of OBI. These findings underscore the importance of vaccination in preventing OBI in high-risk popu

Finally, this review identified a high prevalence of OBI in patients with HCC, ranging from 3.2% to 59.4%[41,97]. Notably, the presence of OBI in HCC patients has been associated with more aggressive tumors and a poorer prognosis[9,98], emphasizing the critical need for routine screening for OBI in HCC patients.

It should be noted that the HBV DNA detection methods used in the studies selected for this literature review greatly influence the reported results, due to their variable sensitivity as well as their heterogeneity in the different analytical steps[86,116]. This methodological variability results in observed OBI prevalences that vary widely across studies. This is an important limitation to consider when interpreting the OBI prevalence data from this literature review.

Studies on the prevalence of OBI are limited. However, our review highlights the significant burden of OBI in various high-risk populations, including patients with CHC, haemodialysis patients, patients with HCC, and thalassemia patients. The high prevalence of OBI in these studied populations underscores the need to increase HBV screening in order to vaccinate non-infected patients and monitor those who are positive or have an OBI. Further studies are required to better understand the transmission and pathogenesis of OBI and to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies.

The researchers of the associated laboratories and all those who contributed to improving this manuscript. We thank the researchers at the Transmissible Diseases Laboratory, the -Molecular Biology and Genetics Laboratory, and all those who contributed to improving this manuscript.

| 1. | Raimondo G, Locarnini S, Pollicino T, Levrero M, Zoulim F, Lok AS; Taormina Workshop on Occult HBV Infection Faculty Members. Update of the statements on biology and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2019;71:397-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Saitta C, Pollicino T, Raimondo G. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection: An Update. Viruses. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Feld J, Janssen HL, Abbas Z, Elewaut A, Ferenci P, Isakov V, Khan AG, Lim SG, Locarnini SA, Ono SK, Sollano J, Spearman CW, Yeh CT, Yuen MF, LeMair A; Review Team:. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline Hepatitis B: September 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:691-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. |

| 5. | Candotti D, Boizeau L, Laperche S. Occult hepatitis B infection and transfusion-transmission risk. Transfus Clin Biol. 2017;24:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kengne M, Medja YFO, Tedom, Nwobegahay JM. [Residual risk for transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection due to occult hepatitis B virus infection in donors living in Yaoundé, Cameroon]. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Owiredu W, Osei-Yeboah J, Amidu N, Laing EF. Residual Risk of Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus through Blood Transfusion in Ghana: Evaluation of the performance of Rapid Immunochromatographic Assay with Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. J Med Biomed Sci. 2012;1:17-28. |

| 8. | Yooda AP, Sawadogo S, Soubeiga ST, Obiri-Yeboah D, Nebie K, Ouattara AK, Diarra B, Simpore A, Yonli YD, Sawadogo AG, Drabo BE, Zalla S, Siritié AP, Nana RS, Dahourou H, Simpore J. Residual risk of HIV, HCV, and HBV transmission by blood transfusion between 2015 and 2017 at the Regional Blood Transfusion Center of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. J Blood Med. 2019;10:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mak LY, Wong DK, Pollicino T, Raimondo G, Hollinger FB, Yuen MF. Occult hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, virology, hepatocarcinogenesis and clinical significance. J Hepatol. 2020;73:952-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang ZH, Wu CC, Chen XW, Li X, Li J, Lu MJ. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:126-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 11. | Assih M, Ouattara AK, Diarra B, Yonli AT, Compaore TR, Obiri-Yeboah D, Djigma FW, Karou S, Simpore J. Genetic diversity of hepatitis viruses in West-African countries from 1996 to 2018. World J Hepatol. 2018;10:807-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 12. | Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, Craxì A, Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB, Gerlich WH, Levrero M, Locarnini S, Michalak T, Mondelli MU, Pawlotsky JM, Pollicino T, Prati D, Puoti M, Samuel D, Shouval D, Smedile A, Squadrito G, Trépo C, Villa E, Will H, Zanetti AR, Zoulim F. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bhattacharya H, Bhattacharya D, Roy S, Sugunan AP. Occult hepatitis B infection among individuals belonging to the aboriginal Nicobarese tribe of India. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:1630-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pollicino T, Saitta C. Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5951-5961. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vallet-Pichard A, Pol S. [Occult hepatitis B virus infection]. Virologie (Montrouge). 2008;12:87-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis. 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06. |

| 17. | Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. Transfus Clin Biol. 2004;11:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 48656] [Article Influence: 2862.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Mateo S. Procédure pour conduire avec succès une revue de littérature selon la méthode PRISMA. Kinésithérapie Rev. 2020;20:29-37. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Elrashidy H, El-Didamony G, Elbahrawy A, Hashim A, Alashker A, Morsy MH, Elwassief A, Elmestikawy A, Abdallah AM, Mohammad AG, Mostafa M, George NM, Abdelhafeez H. Absence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in sera of diabetic children and adolescents following hepatitis B vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:2336-2341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Elsawaf GEDA, Mahmoud OEK, Shawky SM, Mohamed HMM, Alsumairy HHA. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection on antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. Alex J Med. 2015;51:241-246. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tao I, Compaoré TR, Diarra B, Djigma F, Zohoncon TM, Assih M, Ouermi D, Pietra V, Karou SD, Simpore J. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses in the general population of burkina faso. Hepat Res Treat. 2014;2014:781843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Meda N, Tuaillon E, Kania D, Tiendrebeogo A, Pisoni A, Zida S, Bollore K, Medah I, Laureillard D, Moles JP, Nagot N, Nebie KY, Van de Perre P, Dujols P. Hepatitis B and C virus seroprevalence, Burkina Faso: a cross-sectional study. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:750-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Somda KS, Sermé AK, Coulibaly A, Cissé K, Sawadogo A, Sombié AR, Bougouma A. Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Should Not Be the Only Sought Marker to Distinguish Blood Donors towards Hepatitis B Virus Infection in High Prevalence Area. Open J Gastroenterol. 2016;6:362-372. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Ky/Ba A, Sanou M, Ouédraogo AS, Sourabié IB, Ky AY, Sanou I, Ouédraogo/Traoré R, Sangaré L. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2021;22:359-364. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Diarra B, Yonli AT, Sorgho PA, Compaore TR, Ouattara AK, Zongo WA, Tao I, Traore L, Soubeiga ST, Djigma FW, Obiri-Yeboah D, Nagalo BM, Pietra V, Sanogo R, Simpore J. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Associated Genotypes among HBsAg-negative Subjects in Burkina Faso. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2018;10:e2018007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ndow G, Cessay A, Cohen D, Shimakawa Y, Gore ML, Tamba S, Ghosh S, Sanneh B, Baldeh I, Njie R, D'Alessandro U, Mendy M, Thursz M, Chemin I, Lemoine M. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Occult Hepatitis B Infection in The Gambia, West Africa. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:862-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jepkemei KB, Ochwoto M, Swidinsky K, Day J, Gebrebrhan H, McKinnon LR, Andonov A, Oyugi J, Kimani J, Gachara G, Songok EM, Osiowy C. Characterization of occult hepatitis B in high-risk populations in Kenya. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Elmaghloub R, Elbahrawy A, El Didamony G, Hashim A, Morsy MH, Hantour O, Hantour A, Abdelbaseer M. Occult hepatitis B infection in Egyptian health care workers. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sondlane TH, Mawela L, Razwiedani LL, Selabe SG, Lebelo RL, Rakgole JN, Mphahlele MJ, Dochez C, De Schryver A, Burnett RJ. High prevalence of active and occult hepatitis B virus infections in healthcare workers from two provinces of South Africa. Vaccine. 2016;34:3835-3839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schmeltzer P, Sherman KE. Occult hepatitis B: clinical implications and treatment decisions. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3328-3335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Madihi S, Syed H, Lazar F, Zyad A, Benani A. A Systematic Review of the Current Hepatitis B Viral Infection and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Situation in Mediterranean Countries. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:7027169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bashir RA, Hassan T. High Incidence of Occult Hepatitis B Infection (OBI) among Febrile Patients in Atbara City, Northern Sudan. J Infect Dis Res. 2019;51-54 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/KhalidEnan/publication/336304934_High_Incidence_of_Occult_Hepatitis_B_Infection_OBI_among_Febrile_Patients_in_Atbara_City_Northern_Sudan/links/5d9ae940a6fdccfd0e7f06b0/High. |

| 34. | Meschi S, Schepisi MS, Nicastri E, Bevilacqua N, Castilletti C, Sciarrone MR, Paglia MG, Fumakule R, Mohamed J, Kitwa A, Mangi S, Molteni F, Di Caro A, Vairo F, Capobianchi MR, Ippolito G. The prevalence of antibodies to human herpesvirus 8 and hepatitis B virus in patients in two hospitals in Tanzania. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1569-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lin C, Kao J. Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes: Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Implications. Curr Hepat Rep. 2013;124-132. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Youssef A, Yano Y, El-Sayed Zaki M, Utsumi T, Hayashi Y. Characteristics of hepatitis viruses among Egyptian children with acute hepatitis. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1459-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Aluora PO, Muturi MW, Gachara G. Seroprevalence and genotypic characterization of HBV among low risk voluntary blood donors in Nairobi, Kenya. Virol J. 2020;17:176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Meier-Stephenson V, Deressa T, Genetu M, Damtie D, Braun S, Fonseca K, Swain MG, van Marle G, Coffin CS. Prevalence and molecular characterization of occult hepatitis B virus in pregnant women from Gondar, Ethiopia. Can Liver J. 2020;3:323-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yousif M, Mudawi H, Hussein W, Mukhtar M, Nemeri O, Glebe D, Kramvis A. Genotyping and virological characteristics of hepatitis B virus in HIV-infected individuals in Sudan. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Esmail MA, Mahdi WK, Khairy RM, Abdalla NH. Genotyping of occult hepatitis B virus infection in Egyptian hemodialysis patients without hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:452-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hassan ZK, Hafez MM, Mansor TM, Zekri AR. Occult HBV infection among Egyptian hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Virol J. 2011;8:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Taha SE, El-Hady SA, Ahmed TM, Ahmed IZ. Detection of occult HBV infection by nested PCR assay among chronic hepatitis C patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2013;14:353-360. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Youssef A, Yano Y, Utsumi T, abd El-alah EM, abd El-Hameed Ael-E, Serwah Ael-H, Hayashi Y. Molecular epidemiological study of hepatitis viruses in Ismailia, Egypt. Intervirology. 2009;52:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Patel NH, Meier-Stephenson V, Genetu M, Damtie D, Abate E, Alemu S, Aleka Y, Van Marle G, Fonseca K, Coffin CS, Deressa T. Prevalence and genetic variability of occult hepatitis B virus in a human immunodeficiency virus positive patient cohort in Gondar, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lin CL, Kao JH. Hepatitis B virus Genotypes and Variants. CSH PERSPECTIVES. 2015;5:021436. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Abd El Kader Mahmoud O, Abd El Rahim Ghazal A, El Sayed Metwally D, Elnour AM, Yousif GE. Detection of occult hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors in Sudan. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:14-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Peliganga LB, Mello VM, de Sousa PSF, Horta MAP, Soares ÁD, Nunes JPDS, Nobrega M, Lewis-Ximenez LL. Transfusion Transmissible Infections in Blood Donors in the Province of Bié, Angola, during a 15-Year Follow-Up, Imply the Need for Pathogen Reduction Technologies. Pathogens. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Said ZN, Sayed MH, Salama II, Aboel-Magd EK, Mahmoud MH, Setouhy ME, Mouftah F, Azzab MB, Goubran H, Bassili A, Esmat GE. Occult hepatitis B virus infection among Egyptian blood donors. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:64-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | El-Zayadi AR, Ibrahim EH, Badran HM, Saeid A, Moneib NA, Shemis MA, Abdel-Sattar RM, Ahmady AM, El-Nakeeb A. Anti-HBc screening in Egyptian blood donors reduces the risk of hepatitis B virus transmission. Transfus Med. 2008;18:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | El-Sherif AM, Abou-Shady MA, Al-Hiatmy MA, Al-Bahrawy AM, Motawea EA. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in Egyptian blood donors negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. Hepatol Int. 2007;1:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Mabunda N, Zicai AF, Ismael N, Vubil A, Mello F, Blackard JT, Lago B, Duarte V, Moraes M, Lewis L, Jani I. Molecular and serological characterization of occult hepatitis B among blood donors in Maputo, Mozambique. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2020;115:e200006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. |

Akintule OA, Olusola BA, Odaibo GN, Olaleye DO. Occult HBV Infection in Nigeria.

Arch Basic Appl Med. 2018;6 87-93 Available from |

| 53. | Olotu AA, Oyelese AO, Salawu L, Audu RA, Okwuraiwe AP, Aboderin AO. Occult Hepatitis B virus infection in previously screened, blood donors in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: implications for blood transfusion and stem cell transplantation. Virol J. 2016;13:76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nna E, Mbamalu C, Ekejindu I. Occult hepatitis B viral infection among blood donors in South-Eastern Nigeria. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:223-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. |

Hassan AG, Yassin ME, Mohammed AB, Bush NM. Molecular Detection and Sero-frequency Rate of Occult Hepatitis B Virus among Blood Donors in Southern Darfur State (Sudan).

Afr J Med Sci. 2017;2 7 Available from |

| 56. | Mahgoub S, Candotti D, El Ekiaby M, Allain JP. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and recombination between HBV genotypes D and E in asymptomatic blood donors from Khartoum, Sudan. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:298-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Fopa D, Candotti D, Tagny CT, Doux C, Mbanya D, Murphy EL, Kenawy HI, El Chenawi F, Laperche S. Occult hepatitis B infection among blood donors from Yaoundé, Cameroon. Blood Transfus. 2019;17:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kishk R, Nemr N, Elkady A, Mandour M, Aboelmagd M, Ramsis N, Hassan M, Soliman N, Iijima S, Murakami S, Tanaka Y, Ragheb M. Hepatitis B surface gene variants isolated from blood donors with overt and occult HBV infection in north eastern Egypt. Virol J. 2015;12:153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Antar W, El-Shokry MH, Abd El Hamid WA, Helmy MF. Significance of detecting anti-HBc among Egyptian male blood donors negative for HBsAg. Transfus Med. 2010;20:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Fasola FA, Fowotade AA, Faneye AO. Assessment of hepatitis B surface antigen negative blood units for HBV DNA among replacement blood donors in a hospital based blood bank in Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21:1141-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Oluyinka OO, Tong HV, Bui Tien S, Fagbami AH, Adekanle O, Ojurongbe O, Bock CT, Kremsner PG, Velavan TP. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Nigerian Blood Donors and Hepatitis B Virus Transmission Risks. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Candotti D, Allain JP. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:798-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Seo DH, Whang DH, Song EY, Kim HS, Park Q. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen and occult hepatitis B virus infections in Korean blood donors. Transfusion. 2011;51:1840-1846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Zheng X, Ye X, Zhang L, Wang W, Shuai L, Wang A, Zeng J, Candotti D, Allain JP, Li C. Characterization of occult hepatitis B virus infection from blood donors in China. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1730-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Hoffmann CJ, Mashabela F, Cohn S, Hoffmann JD, Lala S, Martinson NA, Chaisson RE. Maternal hepatitis B and infant infection among pregnant women living with HIV in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Firnhaber C, Viana R, Reyneke A, Schultze D, Malope B, Maskew M, Di Bisceglie A, MacPhail P, Sanne I, Kew M. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with isolated core antibody and HIV co-infection in an urban clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:488-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Mbangiwa T, Kasvosve I, Anderson M, Thami PK, Choga WT, Needleman A, Phinius BB, Moyo S, Leteane M, Leidner J, Blackard JT, Mayondi G, Kammerer B, Musonda RM, Essex M, Lockman S, Gaseitsiwe S. Chronic and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Botswana. Genes (Basel). 2018;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Bell TG, Makondo E, Martinson NA, Kramvis A. Hepatitis B virus infection in human immunodeficiency virus infected southern African adults: occult or overt--that is the question. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Carimo AA, Gudo ES, Maueia C, Mabunda N, Chambal L, Vubil A, Flora A, Antunes F, Bhatt N. First report of occult hepatitis B infection among ART naïve HIV seropositive individuals in Maputo, Mozambique. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Salyani A, Shah J, Adam R, Otieno G, Mbugua E, Shah R. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in a Kenyan cohort of HIV infected anti-retroviral therapy naïve adults. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Chadwick D, Doyle T, Ellis S, Price D, Abbas I, Valappil M, Geretti AM. Occult hepatitis B virus coinfection in HIV-positive African migrants to the UK: a point prevalence study. HIV Med. 2014;15:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ryan K, Anderson M, Gyurova I, Ambroggio L, Moyo S, Sebunya T, Makhema J, Marlink R, Essex M, Musonda R, Gaseitsiwe S, Blackard JT. High Rates of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in HIV-Positive Individuals Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy in Botswana. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Gachara G, Magoro T, Mavhandu L, Lum E, Kimbi HK, Ndip RN, Bessong PO. Characterization of occult hepatitis B virus infection among HIV positive patients in Cameroon. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ayana DA, Mulu A, Mihret A, Seyoum B, Aseffa A, Howe R. Occult Hepatitis B virus infection among HIV negative and positive isolated anti-HBc individuals in eastern Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2020;10:22182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Bivigou-Mboumba B, Amougou-Atsama M, Zoa-Assoumou S, M'boyis Kamdem H, Nzengui-Nzengui GF, Ndojyi-Mbiguino A, Njouom R, François-Souquière S. Hepatitis B infection among HIV infected individuals in Gabon: Occult hepatitis B enhances HBV DNA prevalence. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Bivigou-Mboumba B, François-Souquière S, Deleplancque L, Sica J, Mouinga-Ondémé A, Amougou-Atsama M, Chaix ML, Njouom R, Rouet F. Broad Range of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Patterns, Dual Circulation of Quasi-Subgenotype A3 and HBV/E and Heterogeneous HBV Mutations in HIV-Positive Patients in Gabon. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0143869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Attiku K, Bonney J, Agbosu E, Bonney E, Puplampu P, Ganu V, Odoom J, Aboagye J, Mensah J, Agyemang S, Awuku-Larbi Y, Arjarquah A, Mawuli G, Quaye O. Circulation of hepatitis delta virus and occult hepatitis B virus infection amongst HIV/HBV co-infected patients in Korle-Bu, Ghana. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Attia KA, Eholié S, Messou E, Danel C, Polneau S, Chenal H, Toni T, Mbamy M, Seyler C, Wakasugi N, N'dri-Yoman T, Anglaret X. Prevalence and virological profiles of hepatitis B infection in human immunodeficiency virus patients. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Opaleye OO, Oluremi AS, Atiba AB, Adewumi MO, Mabayoje OV, Donbraye E, Ojurongbe O, Olowe OA. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection among HIV Positive Patients in Nigeria. J Trop Med. 2014;2014:796121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Rusine J, Ondoa P, Asiimwe-Kateera B, Boer KR, Uwimana JM, Mukabayire O, Zaaijer H, Mugabekazi J, Reiss P, van de Wijgert JH. High seroprevalence of HBV and HCV infection in HIV-infected adults in Kigali, Rwanda. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Powell EA, Boyce CL, Gededzha MP, Selabe SG, Mphahlele MJ, Blackard JT. Functional analysis of 'a' determinant mutations associated with occult HBV in HIV-positive South Africans. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:1615-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ayuk J, Mphahlele J, Bessong P. Hepatitis B virus in HIV-infected patients in northeastern South Africa: prevalence, exposure, protection and response to HAART. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mayaphi SH, Roussow TM, Masemola DP, Olorunju SA, Mphahlele MJ, Martin DJ. HBV/HIV co-infection: the dynamics of HBV in South African patients with AIDS. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:157-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Mudawi H, Hussein W, Mukhtar M, Yousif M, Nemeri O, Glebe D, Kramvis A. Overt and occult hepatitis B virus infection in adult Sudanese HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | El-Ghitany EM, Farghaly AG, Hashish MH. Occult hepatitis B virus infection among hepatitis C virus seropositive and seronegative blood donors in Alexandria, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Mahmoud OAEK, Ghazal AAER, Metwally DES, Shamseya MM, Hamdallah HM. Detection of occult hepatitis B virus among chronic hepatitis C patients. Alex J Med. 2016;52:115-123. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Kishk R, Atta HA, Ragheb M, Kamel M, Metwally L, Nemr N. Genotype characterization of occult hepatitis B virus strains among Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:130-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Selim HS, Abou-Donia HA, Taha HA, El Azab GI, Bakry AF. Role of occult hepatitis B virus in chronic hepatitis C patients with flare of liver enzymes. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:187-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Emara MH, El-Gammal NE, Mohamed LA, Bahgat MM. Occult hepatitis B infection in egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients: prevalence, impact on pegylated interferon/ribavirin therapy. Virol J. 2010;7:324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | El-Sherif A, Abou-Shady M, Abou-Zeid H, Elwassief A, Elbahrawy A, Ueda Y, Chiba T, Hosney AM. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a screening test for occult hepatitis B virus infection in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:359-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Raouf HE, Yassin AS, Megahed SA, Ashour MS, Mansour TM. Seroprevalence of occult hepatitis B among Egyptian paediatric hepatitis C cancer patients. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:103-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Omar HH, Taha SA, Hassan WH, Omar HH. Impact of schistosomiasis on increase incidence of occult hepatitis B in chronic hepatitis C patients in Egypt. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:761-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Elbahrawy A, Alaboudy A, El Moghazy W, Elwassief A, Alashker A, Abdallah AM. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in Egypt. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1671-1678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Petrick JL, Braunlin M, Laversanne M, Valery PC, Bray F, McGlynn KA. International trends in liver cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype, 1978-2007. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1534-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Ayele TA, Barac A, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bhutta Z, Castillo-Rivas J, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dey S, Dicker D, Phuc H, Ekwueme DU, Zaki MS, Fischer F, Fürst T, Hancock J, Hay SI, Hotez P, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kumar A, Kutz M, Larson H, Lopez A, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, McAlinden C, Meier T, Mendoza W, Mokdad A, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Ogbo F, Patton G, Pereira DM, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Roshandel G, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou S, Shackelford K, Shore H, Sun J, Mengistu DT, Topór-Mądry R, Tran B, Ukwaja KN, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wakayo T, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Yonemoto N, Younis M, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zhu L, Murray CJL, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1459] [Cited by in RCA: 1575] [Article Influence: 175.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Gouas DA, Villar S, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Legros P, Ferro G, Kirk GD, Lesi OA, Mendy M, Bah E, Friesen MD, Groopman J, Chemin I, Hainaut P. TP53 R249S mutation, genetic variations in HBX and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in The Gambia. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1219-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Obika M, Shinji T, Fujioka S, Terada R, Ryuko H, Lwin AA, Shiraha H, Koide N. Hepatitis B virus DNA in liver tissue and risk for hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. A prospective study. Intervirology. 2008;51:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Gissa SB, Minaye ME, Yeshitela B, Gemechu G, Tesfaye A, Alemayehu DH, Shewaye A, Sultan A, Mihret A, Mulu A. Occult hepatitis B virus infection among patients with chronic liver disease of unidentified cause, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Majed AA, El Hussein ARM, Ishag AEH, Madni H, Mustafa MO, Bashir RA, Assan TH, Elkhidir IM, Enan KA. Absence of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Haemodialysis Patients in White Nile State, Sudan. Virol Immunol J. 2018;2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 101. | Mustafa M, Ka E, Im E, Arm EH. Occult Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis B Genotypes among Renal Transplant Patients in Khartoum State, Sudan. J Emerg Dis Virol. 2020;5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 102. | Ibrahim SAE, Mohamed SB, Kambal S, Diya-Aldeen A, Ahmed S, Faisal B, Ismail F, Ibrahim A, Sabawe A, Mohamed O. Molecular Detection of Occult Hepatitis B virus in plasma and urine of renal transplant patients in Khartoum state Sudan. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;97:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Ramezani A, Banifazl M, Mamishi S, Sofian M, Eslamifar A, Aghakhani A. The influence of human leukocyte antigen and IL-10 gene polymorphisms on hepatitis B virus outcome. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Abdel-Maksoud NHM, El-Shamy A, Fawzy M, Gomaa HHA, Eltarabilli MMA. Hepatitis B variants among Egyptian patients undergoing hemodialysis. Microbiol Immunol. 2019;63:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Abu El Makarem MA, Abdel Hamid M, Abdel Aleem A, Ali A, Shatat M, Sayed D, Deaf A, Hamdy L, Tony EA. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in hemodialysis patients from egypt with or without hepatitis C virus infection. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Amer F, Yousif MM, Mohtady H, Khattab RA, Karagoz E, Ayaz KFM, Hammad NM. Surveillance and impact of occult hepatitis B virus, SEN virus, and torque teno virus in Egyptian hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Elgohry I, Elbanna A, Hashad D. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in a cohort of Egyptian chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Lab. 2012;58:1057-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Helaly GF, El Ghazzawi EF, Shawky SM, Farag FM. Occult hepatitis B virus infection among chronic hemodialysis patients in Alexandria, Egypt. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8:562-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Mandour M, Nemr N, Shehata A, Kishk R, Badran D, Hawass N. Occult HBV infection status among chronic hepatitis C and hemodialysis patients in Northeastern Egypt: regional and national overview. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Mohammed AA, Khalid AE, Osama MK, Mohammed OH, Abdel RMEH, Isam ME. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in haemodialysis patients in Khartoum State, Sudan from 2012 to 2014. J Med Lab Diagn. 2015;6:22-26. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 111. | Sahr Hagmohamed S, Isam M, M. El Hussein A, Khalid A. Prevelance of occult Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection among Hemodialysis Patients in Northern State, Sudan. Virol Immunol J. 2019;3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 112. | Ahmed EA, Mohammed AE, Mohamed Nour BY, Talha AA, Hamid Z, Elshafia MA, Salih ME. The Possibilities of Chronic Renal Failure Patients Contracting Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection, Sudan. Adv Microbiol. 2022;12:91-102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 113. | Elkady A, Aboulfotuh S, Ali EM, Sayed D, Abdel-Aziz NM, Ali AM, Murakami S, Iijima S, Tanaka Y. Incidence and characteristics of HBV reactivation in hematological malignant patients in south Egypt. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6214-6220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Elbedewy TA, Elashtokhy HE, Rabee ES, Kheder GE. Prevalence and chemotherapy-induced reactivation of occult hepatitis B virus among hepatitis B surface antigen negative patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: significance of hepatitis B core antibodies screening. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2015;27:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Diop M, Cisse-Diallo VMP, Ka D, Lakhe NA, Diallo-Mbaye K, Massaly A, Dièye A, Fall NM, Badiane AS, Thioub D, Fortes-Déguénonvo L, Lo G, Diop CT, Ndour CT, Soumaré M, Seydi M. [Occult hepatitis B reactivation in a patient with homozygous sickle cell disease: clinical case and literature review]. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Shaker O, Ahmed A, Abdel Satar I, El Ahl H, Shousha W, Doss W. Occult hepatitis B in Egyptian thalassemic children. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:340-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Seo DH, Whang DH, Song EY, Han KS. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and blood transfusion. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:600-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Said ZN, El-Sayed MH, El-Bishbishi IA, El-Fouhil DF, Abdel-Rheem SE, El-Abedin MZ, Salama II. High prevalence of occult hepatitis B in hepatitis C-infected Egyptian children with haematological disorders and malignancies. Liver Int. 2009;29:518-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Amponsah-Dacosta E, Lebelo RL, Rakgole JN, Selabe SG, Gededzha MP, Mayaphi SH, Powell EA, Blackard JT, Mphahlele MJ. Hepatitis B virus infection in post-vaccination South Africa: occult HBV infection and circulating surface gene variants. J Clin Virol. 2015;63:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Singh H, Pradhan M, Singh RL, Phadke S, Naik SR, Aggarwal R, Naik S. High frequency of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with beta-thalassemia receiving multiple transfusions. Vox Sang. 2003;84:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |