INTRODUCTION

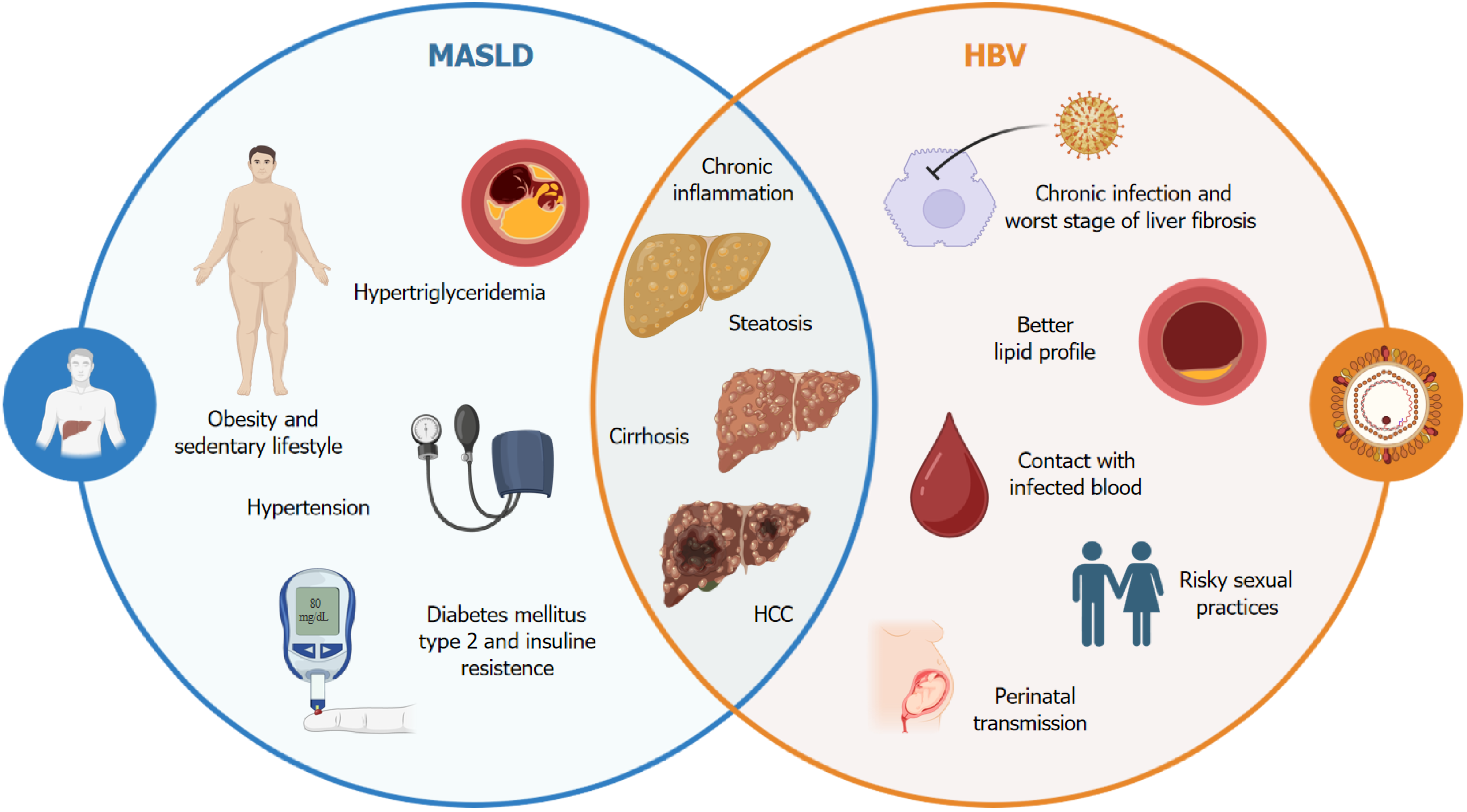

In this editorial, we discuss the study conducted by Wang et al[1], which we read with great interest in the latest issue of the World Journal of Hepatology. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has emerged as the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, driven largely by the global epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus[2,3]. MASLD is not only prevalent in Western countries but also increasingly recognized in regions traditionally associated with viral hepatitis, such as Asia and Africa[4,5]. This dual burden of MASLD and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection represents a unique clinical challenge, as both conditions contribute to the progression of liver disease, potentially leading to more severe outcomes such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Figure 1)[6,7].

Figure 1 Multifactorial interaction between hepatitis B virus and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

The complex relationship between chronic hepatitis B virus infection and the manifestations of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, including a predisposition to hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, is illustrated. Potential mechanisms involve chronic inflammation, metabolic alterations, and changes in the gut microbiome composition. This figure highlights the importance of considering integrated therapeutic interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of this interaction on hepatic and metabolic health. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; MASLD: Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Currently, there is not a universally accepted definition of metabolic dysfunction. Some authors have proposed defining it based on the concept of the metabolic syndrome[8]. Metabolic dysfunction is a broad term that refers to an impaired ability of the body to regulate key metabolic processes, including glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and energy balance. This dysfunction is typically characterized by insulin resistance (IR), dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity, all of which can contribute to the development of various metabolic disorders, including MASLD[9]. The pathophysiology of MASLD is complex and involves multiple interconnected mechanisms, such as IR, inflammation, oxidative stress and lipid metabolism dysregulation[8]. At the heart of this process is IR, which promotes the accumulation of free fatty acids in the liver, leading to hepatic steatosis. As hepatocytes become overloaded with lipids, they undergo metabolic stress, resulting in oxidative stress and the production of proinflammatory cytokines. This inflammatory response, coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress, further exacerbates liver damage. One of the key mechanisms underlying MASLD is the dysregulation of lipid metabolism, where excess triglycerides and fatty acids are deposited in hepatocytes, impairing their normal function. Additionally, adipose tissue dysfunction, which often accompanies obesity, contributes to the release of adipokines and proinflammatory mediators that can promote hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Another crucial aspect of MASLD pathogenesis is the gut-liver axis, where alterations in the gut microbiota can lead to increased intestinal permeability and the translocation of endotoxins to the liver. This process triggers an immune response that amplifies liver inflammation and accelerates fibrosis[9]. These factors contribute to fat accumulation in the liver and chronic inflammation, which can progress to significant liver damage[10]. When MASLD is present along with HBV infection, the clinical scenario is further complicated. HBV infection is a chronic viral condition that can cause persistent liver inflammation, fibrosis and lead to an increased risk of cirrhosis and HCC[11]. The virus integrates into the host genome, allowing it to evade immune detection and persist within hepatocytes. This persistence triggers a chronic immune response, particularly involving cluster of differentiation 8 + T cells, which, although unable to eliminate the virus completely, continue to attack infected hepatocytes in an effort to control viral replication. This ongoing immune attack contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of HBV-related liver damage[12]. The relationship between chronic HBV infection and MASLD remains a subject of ongoing research. Recent studies have demonstrated that the coexistence of chronic HBV infection and MASLD is associated with an increased risk of advanced liver disease and HCC[13,14]. The synergistic interaction between these two diseases aggravates liver pathology, making it imperative that clinicians understand and treat both diseases simultaneously[15]. The dual etiology of liver disease in patients with MASLD and HBV pose complex and multifaceted challenges, requiring an integrated approach for diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management.

MASLD AND HBV INFECTION: DUAL ETIOLOGY OF LIVER DISEASE

The interaction between MASLD and HBV infection in hepatocytes reveals a complex interplay that impacts both metabolic and viral pathways. Importantly, MASLD, characterized by IR, hepatic steatosis, and chronic inflammation, affects the liver’s response to HBV infection. Specifically, MASLD-related lipid accumulation within hepatocytes can impair the host’s immune defenses against HBV, facilitating viral persistence and replication. Additionally, HBV infection in the presence of MASLD may aggravate metabolic dysregulation, leading to increased oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress, further promoting liver inflammation and fibrosis. The co-occurrence of these conditions accelerates liver injury progression, challenging conventional treatment strategies for chronic hepatitis B, as MASLD complicates the assessment of liver fibrosis and disease severity[16].

The pathological mechanisms at play when MASLD and chronic HBV infection coexist reveal that metabolic dysfunctions in MASLD, such as altered lipid metabolism and systemic inflammation, exacerbate HBV-related liver damage. Studies have shown that steatosis induced by MASLD can increase virus-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes, leading to more pronounced liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD than in patients with HBV alone. Furthermore, the combination of MASLD and HBV appears to promote a proinflammatory hepatic environment, increasing the expression of profibrotic markers and activating hepatic stellate cells more aggressively. This dual pathology not only worsens liver damage but also increases the risk of progression to cirrhosis and HCC[17].

The study by Wang et al[1] underscores the complexity of managing patients with concurrent MASLD and HBV and raises critical questions regarding the future direction of research and clinical care in this field. A comprehensive retrospective cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from the Taiwan Biobank, a large population-based database, to assess the impact of the coexistence of MASLD and chronic HBV infection on liver disease progression and clinical outcomes. The study focused on three main groups: Patients with only MASLD, patients with only chronic HBV infection and patients with both MASLD and HBV, referred to as the dual etiology group. The groups were matched by age and sex via the propensity score matching method to ensure comparable baseline characteristics, which allowed a more accurate assessment of the interactions between metabolic dysfunction and chronic viral hepatitis.

The results of this study are particularly noteworthy. Patients with dual etiology (MASLD-HBV) showed more severe liver inflammation, as indicated by higher aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, than did those with MASLD alone. In addition, these patients had higher fibrosis indices, as measured by the fibrosis-4 score, suggesting a greater risk of advanced fibrosis. Despite this, the dual etiology group had a lower incidence of atherosclerosis than the MASLD alone group did, introducing an interesting paradox in the relationship between metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular risk. Another critical finding was the comparison of the lipid profiles between HBV carriers and healthy controls. The study revealed that HBV carriers presented better lipid profiles, characterized by lower triglyceride and cholesterol levels, and a lower prevalence of MASLD than the control group did. These findings suggest that chronic HBV infection may exert a protective effect against the development of MASLD, despite the increased risk of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Furthermore, by focusing on factors associated with advanced liver fibrosis (fibrosis-4 > 2.67) in patients with MASLD, the study identified age, gamma-glutamyl transferase levels, and the presence of chronic HBV infection as independent risk factors. The adjusted odds ratio for chronic HBV infection associated with advanced fibrosis in patients with MASLD was 2.15, highlighting the significant impact of viral infection on the severity of liver disease in the context of metabolic dysfunction.

The findings of Wang et al[1] are consistent with the observations of other studies, which demonstrate that concurrent hepatic steatosis is independently associated with a lower risk of HCC. However, as the burden of metabolic dysfunction increases, the risk of HCC increases significantly in patients with untreated chronic HBV[18]. Additionally, patients with MASLD and chronic HBV infection have been shown to have different clinicopathologic features than those with MASLD alone. These patients tend to present with less severe hepatic steatosis but are more likely to experience increased hepatic inflammation and fibrosis[19]. Finally, a recent study revealed that, in these patients, the presence of metabolic dysfunction-not only the degree of steatosis-plays a crucial role in disease progression. This metabolic burden can lead to more severe outcomes, such as advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, even in the context of mild steatosis[20]. These findings highlight the urgent need for longitudinal studies that can elucidate the long-term outcomes of patients with concurrent MASLD and HBV. Such studies are essential for understanding the natural history of these patients, which in turn will be crucial for developing effective management strategies. As MASLD is increasingly recognized for its significant role in the progression of liver disease, it is important to explore how metabolic dysfunction interacts with HBV infection to influence disease outcomes. Mechanistic studies that delve into the underlying biological interactions between MASLD and HBV are imperative.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

As our understanding of MASLD continues to evolve, it has become evident that clinical guidelines must be updated to reflect these new insights. The recent shift from NAFLD to MASLD underscores the growing recognition of metabolic dysfunction as a central driver of liver disease, moving the focus away from traditional alcohol-related causes[21]. This change highlights the need to reassess current clinical guidelines, especially for patients with dual etiologies, such as MASLD and chronic HBV infection. Given the complex interplay between metabolic and viral factors, updated guidelines should provide clear and comprehensive recommendations for managing these coexisting conditions. Physicians must incorporate the latest evidence to ensure that they are effectively addressing both metabolic and viral components in these patients.

The coinfection of MASLD and chronic HBV presents significant therapeutic challenges, as the presence of HBV complicates treatment decisions and may interact unpredictably with metabolic interventions. Recent advances, such as the therapeutic targeting of sphingolipid metabolism in MASLD, offer promising avenues for addressing the metabolic aspects of liver disease[22]. However, future research should focus on developing personalized treatment strategies that account for the unique pathophysiological mechanisms in patients with both conditions. By stratifying patients based on their metabolic and virological profiles, clinicians can optimize the efficacy of treatments while minimizing adverse effects. Personalized approaches are essential for managing the dual challenges posed by MASLD and HBV, offering the potential for safer and more effective therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, since patients with concurrent MASLD and HBV infection face an increased risk of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, it is crucial to integrate targeted strategies that address the entire MASLD-cirrhosis spectrum to reduce the burden of liver-related complications[23].

To improve long-term outcomes, specific recommendations for managing MASLD and chronic HBV coinfection emphasize early detection and comprehensive treatment approaches. Early detection of hepatic steatosis in HBV patients is suggested, as it can exacerbate liver injury and fibrosis. Regular monitoring of liver function and fibrosis levels is essential, along with lifestyle interventions such as weight management, dietary modifications, and increasing physical activity levels, to mitigate the effects of MASLD. These interventions may also enhance antiviral therapy outcomes by reducing liver inflammation and improving the host immune response to HBV[24]; furthermore, it highlights the need for tailored treatment plans that integrate both metabolic and antiviral therapies, particularly for patients with significant steatosis or advanced fibrosis. The use of statins or other lipid-lowering agents combined with antiviral drugs can offer dual benefits by controlling dyslipidemia and reducing liver inflammation. Individualized risk assessments are crucial for identifying patients at greater risk of cirrhosis or HCC, guiding decisions regarding more aggressive interventions or those requiring closer surveillance[25]. By adopting these combined insights, physicians can take a more nuanced approach to managing MASLD and HBV coinfection, optimizing long-term liver health outcomes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study by Wang et al[1] provides a critical foundation for future research and clinical practice in the management of patients with concurrent MASLD and HBV. By pursuing the research directions outlined above, we can deepen our understanding of this complex interaction and develop more effective strategies for improving patient outcomes. As the global burden of MASLD continues to rise, addressing its interplay with chronic viral infections will be a key challenge for the hepatology community. The integration of new research findings into clinical practice, along with the promotion of public health initiatives, will be essential in combating this emerging health crisis.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade E

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

P-Reviewer: Arslan M; Greco S; Vasudevan D S-Editor: Fan M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ