Published online Oct 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i10.1164

Peer-review started: August 14, 2023

First decision: September 11, 2023

Revised: September 18, 2023

Accepted: October 11, 2023

Article in press: October 11, 2023

Published online: October 27, 2023

Processing time: 71 Days and 5.7 Hours

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a rare and benign lesion that mimics malig

We report a case of a 65-year-old male who presented with fevers, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss following an influenza infection and was found to have multiple hepatic IPT’s following an extensive work up.

Our case highlights the importance of considering hepatic IPT’s in the differential in a patient who presents with symptoms and imaging findings mimicking malignancy shortly following a viral infection.

Core Tip: Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a rare and benign lesion that can develop in any part of the body. Although the pathophysiology remain unclear, it is thought to develop in the setting of infection, inflammation, autoimmunity, trauma, etc. In this case report, we are the first to highlight the development of IPT in the liver in a patient following a recent influenza infection. Our case report emphasizes the importance of including IPT in the differential in a patient who presents with symptoms and radiologic findings concerning for malignancy shortly after a viral infection, such as Influenza.

- Citation: Patel A, Chen A, Lalos AT. Inflammatory pseudotumors in the liver associated with influenza: A case report. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(10): 1164-1169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i10/1164.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i10.1164

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a rare, mostly benign inflammatory solid tumor containing spindle cells, myofibroblasts, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Although IPT can occur in any age, it typically affects children and young adults. The pathophysiology and etiology of IPT is not fully understood and the diagnosis continues to remain one of exclusion. IPTs often mimic malignancy and can develop in various organs, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g., liver). Case reports of IPT involving the GI tract are scarce.

Several hypotheses suggest systemic inflammatory conditions, infection, autoimmune conditions, and trauma/surgical inflammation to be causes of IPT. One case series reported three patients with hepatic IPTs that occurred following either biliary drainage and stent placement or hepatic abscess[1]. Viral infections may contribute to the development of IPTs[2]. A case report of IPT following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination has been reported[3]. However, there are no cases reporting the development of IPT in the GI tract following influenza. We report a case of a 65-year-old male who we believe developed hepatic IPTs following influenza.

A 65 year old male was referred to our hospital after multiple liver masses were detected on computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis.

In March 2023, a 65-year-old male with a history of microcytic anemia due to erosive gastritis, diverticulosis, and diabetes mellitus presented for evaluation of multiple liver masses. He reported high-grade fevers, night sweats, confusion, and unintentional weight loss of 40 pounds weight in a 3-wk timespan that occurred five months prior to presentation in our hepatology clinic.

Patient with a past medical history of microcytic anemia due to erosive gastritis, diverticulosis, and diabetes mellitus.

Personal and family history is noncontributory.

During the general examination, no abnormalities were detected.

Bloodwork at that time revealed a microcytic anemia of hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 191.0 mg/L and > 130 mm/h, respectively. He was initially diagnosed with influenza A via PCR of nasal swab.

Alpha-fetoprotein, hepatitis B (core and surface antibody) and C, antinuclear antibody, mitochondrial antibody, actin (smooth muscle) antibody and carcinoembryonic antigen were all negative. IgG antibody titers to hepatitis B surface antibody were low/non-immune. Cancer antigen 19-9 was measured at 42 U/mL (reference range: 0-35 U/mL).

A CT scan was performed, which showed heterogeneous left hepatic lobe masses measuring 5.0 cm × 3.0 cm, 4.0 cm × 3.1 cm and 4.1 cm × 3.7 cm as well as a hypodense right hepatic lobe mass measuring 1.1 cm × 1.1 cm (Figure 1). Adenopathy of the periportal, paraceliac, and multiple mediastinal lymph nodes were noted. The patient was referred to oncology for presumed metastatic malignancy and underwent a positron emission tomography (PET) scan which showed small focal areas of uptake. However, the overall uptake of the left lobe hepatic masses appeared similar to the remainder of the liver (Figure 2).

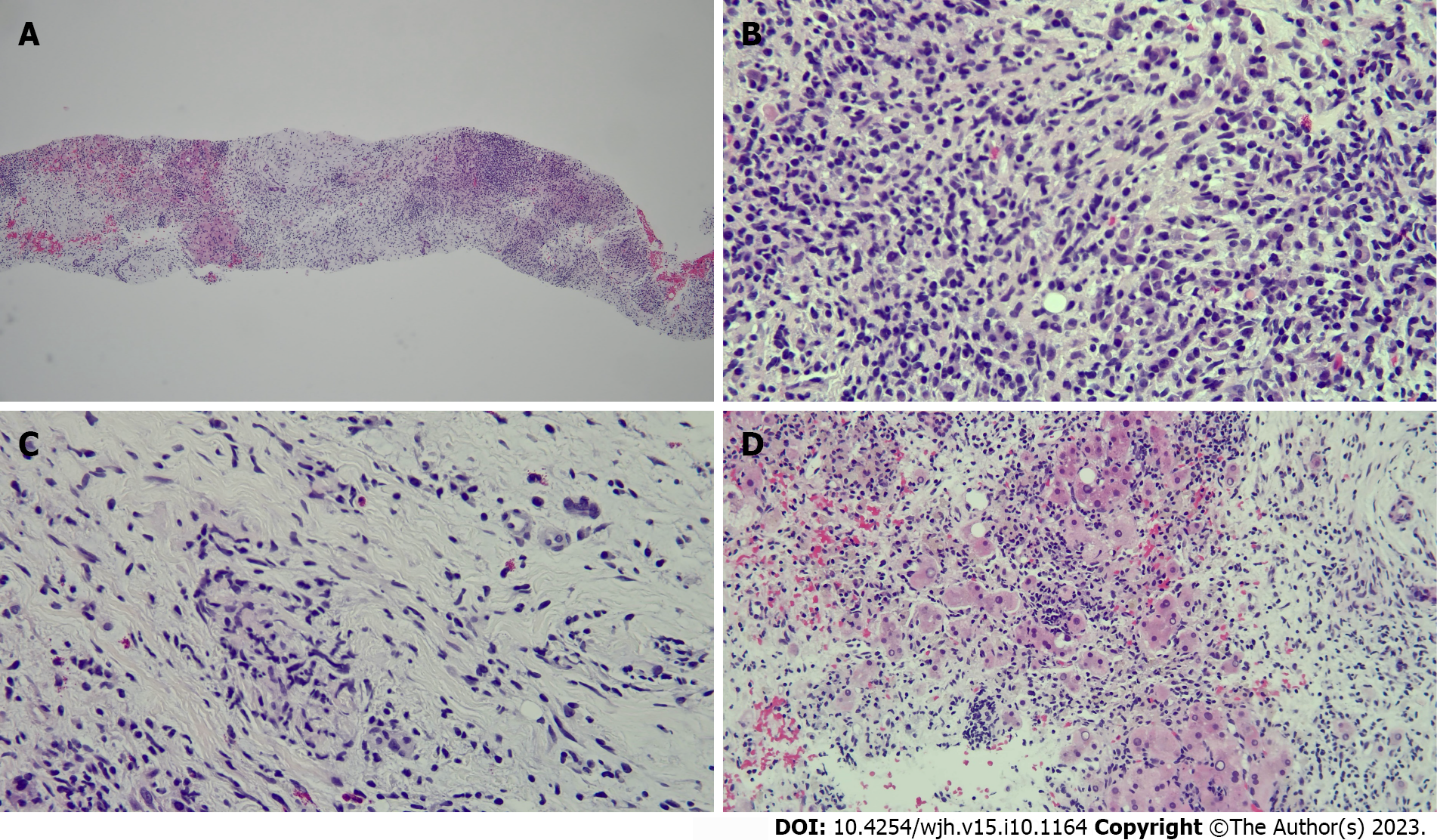

Biopsy of the liver masses showed inflammatory cells but no malignant cells, and subsequent core biopsies revealed replacement of multiacinar liver parenchyma by fibrous and myxoid stroma with dense lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate (Figure 3). Trichrome stain highlighted dense fibrosis, CK7 immunostain showed preserved bile ducts, and smooth muscle actin immunostain showed extensive reactivity in the fibrous stroma. Immunostains for IgG4 and ALK1 were negative.

The patient was subsequently referred to hepatology and underwent a repeat CT scan, which showed a decrease in size of the left hepatic lobe masses and resolution of the right hepatic lobe mass. Previously enlarged lymph nodes either decreased in size or remained stable except for a 1.1 cm × 0.9 cm soft tissue density anterior to the left hepatic lobe which was suspicious for a new lymph node. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were performed to investigate his microcytic anemia and were significant for erosive gastritis.

Based on radiologic and histologic examination of the liver masses, the patient was diagnosed with inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver.

The treatment of hepatic IPTs in our patient was conservative management with supportive care and serial imaging to ensure resolution.

Serial CT imaging showed significant improvement in lymphadenopathy, significant decrease in size of the left hepatic lobe masses, and resolution of the right hepatic lobe mass. Normalization of inflammatory marker (CRP). Patient has returned to his baseline health and weight.

IPT is a benign, rare disease process which mimics malignancy on both clinical and imaging findings. It can present as a solitary mass or multiple masses composed of polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate. Although it can occur anywhere in the body and at any age, it is more typically found in the lungs and occurs more commonly in children and young adults. Hepatic IPT is a rare phenomenon first described by Pack and Baker[4] in 1953 and is most frequently seen in men[5,6].

Although the pathophysiology and etiology of hepatic IPT remains unclear, infection and autoimmune disorders are thought to be a few of the causes. Various infectious agents have been hypothesized to play a role in the development of IPTs, such as Mycoplasma and Nocardia in lung, Epstein-Barr virus in the spleen and lymph nodes, mycobacteria in spindle cell tumors, and Actinomycetes in liver pseudotumors[5]. Recently, a patient with human immunodeficiency virus was diagnosed with biopsy-proven, herpes simplex virus-positive pseudotumor in the gastroesophageal junction[7]. Otherwise, IPT’s have been associated with autoimmune conditions such as IgG4-related disease. Interleukin 1, a cytokine produced by monocytes and macrophages, contributes to the local and systemic effects of IPT. Although treatment of GI IPT’s with surgical resection is usually curative, other reports have shown response to steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and thalidomide. The reported recurrence rate of GI IPT’s is between 18% and 40%[8]. If there is recurrence following initial therapy, surgical resection is highly advised. Spontaneous regression and malignant transformation have also been rarely reported.

While diagnosis and differentiation of IPT from other etiologies requires histologic examination of the tissue, radiographic characteristics may be helpful in ascertaining whether there is potential of the tumor to be malignant[9]. CT and magnetic resonance imaging findings are variable which is attributed to the variability in histologic composition[10]. Similarly, contrast enhanced ultrasound was unable to solely differentiate IPT from other hepatic malignancies[11,12]. However, several imaging characteristics have been studied and may help guide diagnostic workup[13,14].

We believe our case is likely a consequence of the inflammatory state caused by influenza. The temporal association with contracting influenza may be coincidental but the patient does not have any other risk factors including recent infections, malignancy, immunosuppression, trauma, or autoimmune conditions. Our diagnosis of IPT is supported by the lack of uptake on PET-CT, the absence of malignant cells on biopsy, the presence of mixed inflammatory infiltrate and fibrosis on cytopathology, and the resolution with anti-viral treatment directed against influenza.

Due to the rarity of hepatic IPT’s and their features mirroring that of malignancy, our case highlights the importance of including pseudotumor in the differential diagnoses of a new liver mass(es) associated with regional lymphadenopathy following a viral infection, such as Influenza. To date, there have been no reported cases of IPT following influenza and therefore would add to current gaps in knowledge when evaluating patients with masses concerning for malignancy.

| 1. | Zhao J, Olino K, Low LE, Qiu S, Stevenson HL. Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor: An Important Differential Diagnosis in Patients With a History of Previous Biliary Procedures. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang Z, Jin F, Sun L, Wu H, Chen B, Cui Y. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the thymus: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1414-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yucel Gencoglu A, Mangan MS. Orbital Inflammatory Pseudotumor following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:1141-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pack GT, Baker HW. Total right hepatic lobectomy; report of a case. Ann Surg. 1953;138:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patnana M, Sevrukov AB, Elsayes KM, Viswanathan C, Lubner M, Menias CO. Inflammatory pseudotumor: the great mimicker. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W217-W227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park JY, Choi MS, Lim YS, Park JW, Kim SU, Min YW, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC. Clinical features, image findings, and prognosis of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a multicenter experience of 45 cases. Gut Liver. 2014;8:58-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kripalani S, Williams J, Joneja U, Bansal P, Spitz F. Herpes Simplex Virus Pseudotumor Masking as Gastric Malignancy. ACG Case Rep J. 2023;10:e00985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sanders BM, West KW, Gingalewski C, Engum S, Davis M, Grosfeld JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the alimentary tract: clinical and surgical experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bian Y, Jiang H, Zheng J, Shao C, Lu J. Basic Pancreatic Lesions: Radiologic-pathologic Correlation. J Transl Int Med. 2022;10:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawaguchi T, Mochizuki K, Kizu T, Miyazaki M, Yakushijin T, Tsutsui S, Morii E, Takehara T. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver and spleen diagnosed by percutaneous needle biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liao M, Wang C, Zhang B, Jiang Q, Liu J, Liao J. Distinguishing Hepatocellular Carcinoma From Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor Using a Nomogram Based on Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound. Front Oncol. 2021;11:737099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kong WT, Wang WP, Shen HY, Xue HY, Liu CR, Huang DQ, Wu M. Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor mimicking malignancy: the value of differential diagnosis on contrast enhanced ultrasound. Med Ultrason. 2021;23:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kong WT, Wang WP, Cai H, Huang BJ, Ding H, Mao F. The analysis of enhancement pattern of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor on contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Möller K, Stock B, Ignee A, Zadeh ES, De Molo C, Serra C, Jenssen C, Lim A, Görg C, Dong Y, Klinger C, Tana C, Meloni MF, Sparchez Z, Francica G, Dirks K, Hollerweger A, Kinkel H, Weskott HP, Montagut NE, Srivastava D, Dietrich CF. Comments and illustrations of the WFUMB CEUS liver guidelines: Rare focal liver lesions - non-infectious, non-neoplastic. Med Ultrason. 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ataei-Pirkooh A, Iran; Francica G, Italy; Liu K, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Lin C