Published online Apr 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i4.854

Peer-review started: November 20, 2021

First decision: January 12, 2022

Revised: February 3, 2022

Accepted: March 26, 2022

Article in press: March 26, 2022

Published online: April 27, 2022

Processing time: 152 Days and 20 Hours

Spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation of the liver is a rare entity. It may mimic pulmonary mass especially in the absence of trauma. Cough is a common side effect of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors that may cause diaphragmatic rupture due to a sudden increase in trans-diaphragmatic pressure. We present a case of ACE-inhibitor associated spontaneous herniation of the liver mimicking pleural mass.

An 80-year-old woman presented with dry cough for 1 mo and sudden onset of cramping abdominal pain for 1 d. She denied history of trauma, prior surgeries, smoking, alcohol or illicit drug use. She has a history of diabetes and was started on an ACE inhibitor 6 mo ago for the management of hypertension. Examination was remarkable for right upper quadrant tenderness. Lab work-up was unremarkable. Chest X-ray showed a right lower lung opacity suspecting right pleural mass. Chest computed tomography scan ruled out pleural mass, however, revealed herniated right lobe of the liver (3.9 cm × 3.6 cm × 3.4 cm) into the thoracic cavity through the posterolateral diaphragmatic defect. Laparoscopic repair of the diaphragmatic defect was performed and the ACE inhibitor was stopped. Patients’ symptoms had completely resolved on follow-up.

ACE inhibitor-associated cough may cause diaphragmatic liver herniation mimicking pleural mass. Early diagnosis, surgical repair and addressing the triggering factors improve patients’ outcomes.

Core Tip: Diaphragmatic herniation of the liver secondary to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors induced cough is uncommon. Cough is a rare cause of diaphragmatic liver herniation and it may be overlooked. This case illustrates the importance of combining clinical presentation with cross-sectional radiological imaging for early diagnosis and surgical repair of diaphragmatic liver herniation and for better patient outcomes.

- Citation: Tebha SS, Zaidi ZA, Sethar S, Virk MAA, Yousaf MN. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor associated spontaneous herniation of liver mimicking a pleural mass: A case report. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(4): 854-859

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i4/854.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i4.854

Spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity is an uncommon entity. A congenital defect in the diaphragm is the most common cause of diaphragmatic hernia with a reported incidence of 0.8-5 per 10000 births[1]. Acquired rupture of the diaphragm is most commonly caused by high-velocity blunt or penetration abdomino-thoracic trauma and postsurgical diaphragmatic defect that may result in herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity[2,3]. Spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation is an uncommon subtype of acquired hernia without history of trauma. Commonly herniated abdominal organs are the stomach, small or large intestines, mesentery and spleen[2,4,5]. Spontaneous herniation of the liver into the thoracic cavity due to a non-traumatic rupture of the diaphragm is unusual with only a few cases reported[4,6,7].

Clinical presentation of diaphragmatic hernias are variable depending upon the acuity of diaphragmatic rupture, size of the defect and underlying etiology. Majority of patients present with abdominal pain, chest pain, tachycardia, shortness of breath and cough, however, a subset of patients remain asymptomatic in cases of a small defect in the diaphragm[8]. Diaphragmatic liver herniation may mimic pleural malignancy. A high index of clinical suspicion is required for early identification of diaphragmatic hernias and differentiating them from pleural malignancy with a careful review of cross-sectional radiological imaging of chest and abdomen. We present a case of cough induced spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation of the liver due to the use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor.

An 80-year-old female presented for evaluation of dry cough for 4 wk.

Patient’s cough was severe, persistent, without associated hemoptysis or sputum production. She also reported the sudden onset of upper abdominal pain and mild shortness of breath for 1 d prior to visiting the hospital.

She had past medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension and was started on an ACE inhibitor 6 mo ago for the management of hypertension. She denied history of previous surgery or recent trauma.

Family history was unremarkable.

On examination, the patient was afebrile (98.6 F), tachycardiac (112/min) with an elevated blood pressure (140/80 mmHg) and respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute. Abdominal examination was remarkable for mild right upper quadrant tenderness without evidence of Murphy’s sign or skin bruising. The lower border of the liver was non-palpable; however, a percussion dullness was noted at the right fourth intercostal space of the chest in the midclavicular line. The patient was admitted for further evaluation.

Her baseline blood work including complete blood count, liver function tests and basic metabolic panel were unremarkable except for low hemoglobin and hematocrit (Table 1).

| Lab investigation | Value | Normal range for female |

| Hemoglobin | 9.7 g/dL | 11.1-14.5 g/dL |

| Hematocrit, % | 29 | 35.4-42.0 |

| WBC count | 10.1 × 109/L | 4.0-11.0 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 209 × 109/L | 150-450 × 109/L |

| Urea | 17 mg/dL | 10-50 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.76 mg/dL | 0.6-1.1 mg/dL |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | 0.357 (non-reactive) | 1.0 |

| Hepatitis C virus antibody | 0.090 (non-reactive) | 1.0 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.50 | Up to 1.2 mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.20 | < 0.2 mg/dL |

| Alanine transaminase | 08 | < 34 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 96 | 44-147 U/L |

| GGTP | 22 | < 38 U/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 13 | < 31 U/L |

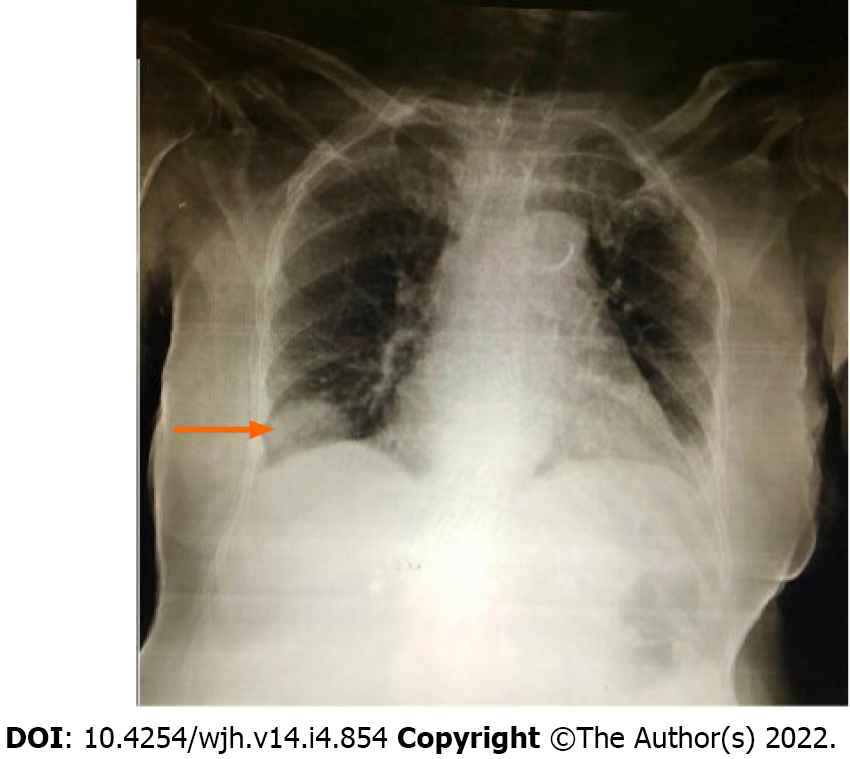

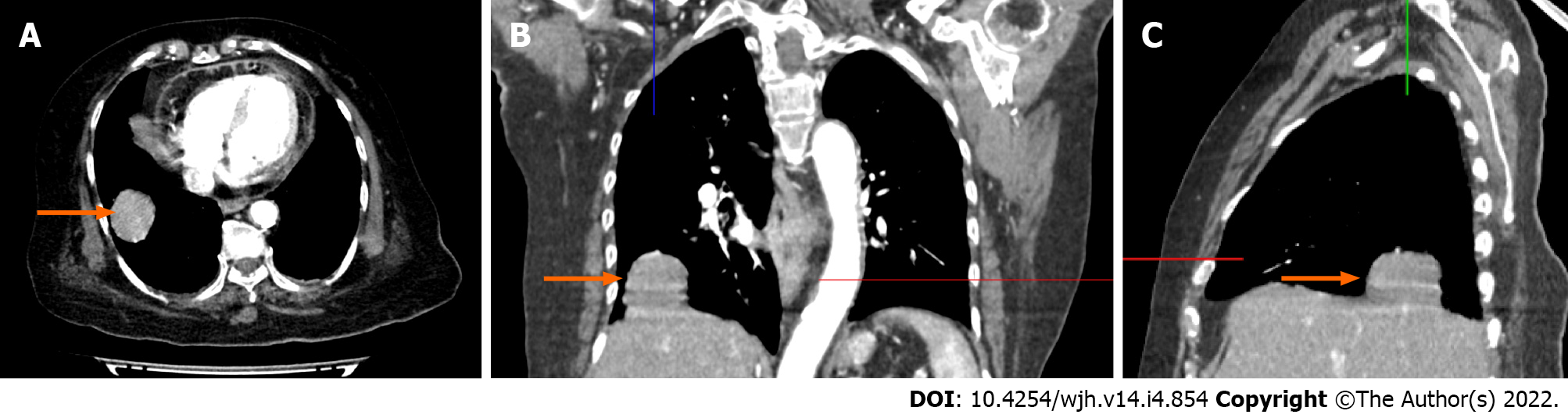

Ultrasound of the abdomen showed normal echotexture of the liver without evidence of liver lesions, cholelithiasis, acute cholecystitis or hepatobiliary ductal dilation. Chest radiograph demonstrated a well-defined soft tissue mass noted just above the right hemidiaphragm making an obtuse angle suggesting pleural or extra-pleural mass (Figure 1). Given a suspicion of pleural malignancy, a high-resolution computed tomography (CT)-scan of the chest was performed which revealed a defect in the posterolateral aspect of the right diaphragm with a herniated right lobe of the liver into the thoracic cavity representing a mass measuring 3.9 cm × 3.6 cm × 3.4 cm (Figure 2).

Spontaneous liver herniation through the right diaphragm due to an ACE inhibitor associated cough.

Laparoscopic surgical repair of the diaphragmatic defect was performed after the retraction of herniated liver into the abdominal cavity. The post-surgical hospital course was uneventful. Patient was discharged on day 3 of hospitalization. Her ACE inhibitor was switched to a calcium channel blocker (verapamil) for the management of hypertension.

At the 8-wk follow-up, the patients’ symptoms were completely resolved and blood pressure was well controlled on Verapamil.

This case illustrates an unusual presentation of spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation of the liver secondary to ACE inhibitor associated cough. ACE inhibitors are common medications used for the management of hypertension and congestive heart failure. Approximately 5%-35% of patients develop ACE inhibitor associated dry cough with a reported onset within hours to months after initiation of therapy[9-11]. Coughing causes an opposing force on the diaphragm due to respiratory muscle discoordination. Abdominal muscle contraction causes an upward pushing force on the diaphragm against the downward and inward movement of the ribs[12]. Sustained cough increases the trans-diaphragmatic pressure gradient that may cause trivial injury to the diaphragm. This phenomenon may result in spontaneous herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity through diaphragmatic defects.

Our patient had an ACE inhibitor associated cough that caused a sudden increase in trans-diaphragmatic pressure and induced liver herniation through a diaphragmatic defect. The herniated liver closely mimicked a pleural mass leading to a diagnosis of suspected malignancy particularly in the setting of new onset of cough and shortness of breath. Our case was initially misdiagnosed as a pleural malignancy due to the rarity of the finding and confusing it with other causes of pulmonary origin. Investigation with chest CT scan ruled out pleural malignancy and revealed diaphragmatic defect with liver herniation. Pataka et al[13] presented a similar case of liver herniation which mimicked lung malignancy due to the gastrointestinal reflux associated with sustained cough.

The sensitivity of chest radiography to differentiate diaphragmatic liver herniation from the pulmonary mass is only 17% in right sided and 46% on left sided diaphragmatic defects[14]. Helical CT scan of the chest and abdomen is the radiological imaging of choice with a 73% sensitivity and a 90% specificity in the identification of diaphragmatic defects, herniated abdominal organs and differentiating them from pulmonary mass[15]. Small diaphragmatic defects may be difficult to locate on CT scan. In these cases, magnetic resonance imaging, diagnostic thoracoscopy or laparoscopy may assist in the identification of diaphragmatic defects and in the planning of surgical repair[8]. Surgical reduction of herniated abdominal contents and repair of the diaphragmatic defect is the treatment of choice. Laparoscopic and/or thoracoscopic repair is preferred over open laparotomy or thoracostomy because of less risk of morbidity and mortality with these minimally invasive modalities[8].

Spontaneous diaphragmatic herniation of the liver may mimic a pleural/pulmonary mass. A high index of clinical suspicion is required for early identification of non-traumatic diaphragmatic liver herniation particularly in individuals at risk of the increased transabdominal pressure gradient. ACE inhibitor associated cough is a known adverse reaction that rarely results in liver herniation. Early diagnosis with cross-sectional radiological imaging, surgical repair and addressing triggering factors improves patient outcome.

| 1. | Chandrasekharan PK, Rawat M, Madappa R, Rothstein DH, Lakshminrusimha S. Congenital Diaphragmatic hernia - a review. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Zaidi ZA, Tebha SS, Sethar SS, Mishra S. Incidental Finding of Right-Sided Idiopathic Spontaneous Acquired Diaphragmatic Hernia. Cureus. 2021;13:e15793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Amreen S, Qayoom Z, Nazir N, Shaheen F, Gojwari T. Post-esophagectomy diaphragmatic hernia—a case series. EurSurg. 2019;271. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gupta S, Kulshreshtha R, Chhabra SK. Non-traumatic herniation of the liver in an asthmatic patient. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:169-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sheer TA, Runyon BA. Recurrent massive steatosis with liver herniation following transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1324-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Warbrick-Smith J, Chana P, Hewes J. Herniation of the liver via an incisional abdominal wall defect. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Farinacci-Vilaró M, Gerena-Montano L, Nieves-Figueroa H, Garcia-Puebla J, Fernández R, Hernández R, González M, Quintana C. Chronic cough causing unexpected diaphragmatic hernia and chest wall rupture. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:15-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rashid F, Chakrabarty MM, Singh R, Iftikhar SY. A review on delayed presentation of diaphragmatic rupture. World J EmergSurg. 2009;4:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mello CJ, Irwin RS, Curley FJ. Predictive values of the character, timing, and complications of chronic cough in diagnosing its cause. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:997-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smyrnios NA, Irwin RS, Curley FJ. Chronic cough with a history of excessive sputum production. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of the diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Chest. 1995;108:991-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:169S-173S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hillenbrand A, Henne-Bruns D, Wurl P. Cough induced rib fracture, rupture of the diaphragm and abdominal herniation. World J EmergSurg. 2006;1:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pataka A, Paspala A, Sourla E, Bagalas V, Argyropoulou P. Non traumatic liver herniation due to persistent cough mimicking a pulmonary mass. Hippokratia. 2013;17:376-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gelman R, Mirvis SE, Gens D. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt trauma: sensitivity of plain chest radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sirbu H, Busch T, Spillner J, Schachtrupp A, Autschbach R. Late bilateral diaphragmatic rupture: challenging diagnostic and surgical repair. Hernia. 2005;9:90-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Amreen S, India; Daoud A, Egypt S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH