Published online Mar 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i3.525

Peer-review started: November 25, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 11, 2022

Accepted: February 15, 2022

Article in press: February 15, 2022

Published online: March 27, 2022

Processing time: 118 Days and 19.8 Hours

With a globally estimated 58 million people affected by, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection still represents a hard challenge for scientific community. A chronic course can occur among patients with a weak innate ad adaptive response with cirrhosis and malignancies as main consequences. Oncologic patients undergoing chemotherapy represent a special immunocompromised population predisposed to HCV reactivation (HCVr) with undesirable changes in cancer treatment and outcome. Aim of the study highlight the possibility of HCVr in oncologic population eligible to chemotherapy and its threatening consequences on cancer treatment; underline the importance of HCV screening before oncologic therapy and the utility of direct aging antivirals (DAAs). A comprehensive overview of scientific literature has been made. Terms searched in PubMed were: “HCV reactivation in oncologic setting” “HCV screening”, “second generation DAAs”. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamics characteristics of DAAs are reported, along with drug - drug interactions among chemotherapeutic drug classes regimens and DAAs. Clinical trials conducted among oncologic adults with HCV infection eligible to both chemotherapy and DAAs were analyzed. Viral eradication with DAAs in oncologic patients affected by HCV infection is safe and helps liver recovery, allowing the initiation of cancer treatment no compromising its course and success.

Core Tip: Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a hard clinical challenge, especially regarding oncologic patients eligible to chemotherapy. HCV reactivation in this setting of population is due to iatrogenic immunosuppression and can impair cancer treatment and outcome. Several specialists still do not prescribe direct aging antivirals to oncologic patients affected by HCV infection, because no univocal guidelines on HCV treatment in oncologic setting are available. The review highlights the importance of screening HCV infection before starting oncologic treatment, the safety of direct aging antivirals treatment under chemotherapy and the utility of treating HCV infection in oncologic setting no compromising chemotherapy course and success.

- Citation: Spera AM. Safety of direct acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in oncologic setting: A clinical experience and a literature review. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(3): 525-534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i3/525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i3.525

Hepatitis C is a viral infection due to a single-stranded RNA enveloped virus, with a mainly hepatic trophism. Eight genotypes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) along with several different subtypes have been identified[1,2]. Since its discovery, in 1989, 184 million patients with hepatitis C have been reported worldwide[3], and 40% of hepatic transplantations performed until 2009 were due to HCV-based liver cirrhosis[1]. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 58 million people worldwide live with chronic HCV infection in 2021, with approximately 1.5 million new infections occurring per year, and approximately 400000 people died from hepatitis C, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, in 2019[3].

The interplay between viral replication and a patient’s immune response determines the biological course of HCV infection[4], considering that viral immune tropism secondary to hepatocyteinfection activates the innate and adaptive immune systems.

The typical outcome of primary infection in immunocompetent subjects is a self-limited illness with spontaneous resolution after an acute phase, characterized by host-protective antibody production. Otherwise, a chronic course of hepatitis has been often described in exposed patients, with weak innate and adaptive immune responses determining an insufficient reduction in viral load, despite concomitant liver function recovery[4]. Consequences of chronicity are cirrhosis and hepatocarcinogenesis[5,6], along with haematologic malignancies, including B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[7], intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and other solid tumours, such as head and neck, colorectal, renal, and pancreatic cancers[7,8,9]. Any kind of immune central reconstitution after immunosuppressive medication can trigger viral reactivation in this chronic setting of HCV, with diversified clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic flares of transaminases to severe liver damage[4].

Approximately two weeks before hepatitis flares, an increase in viral RNA often occurs[4]. Hepatitis C reactivation is therefore defined by an increase in HCV-RNA > 1 Log IU/mL over baseline, while the detection of anti-HCV antibodies cannot help in distinguishing between acute and chronic infection but can determine only the occurrence of an infection[10]. Early identification of HCV infection and/or its reactivation can be merely ensured only by liver function testing and anti-HCV and viral load level surveillance.

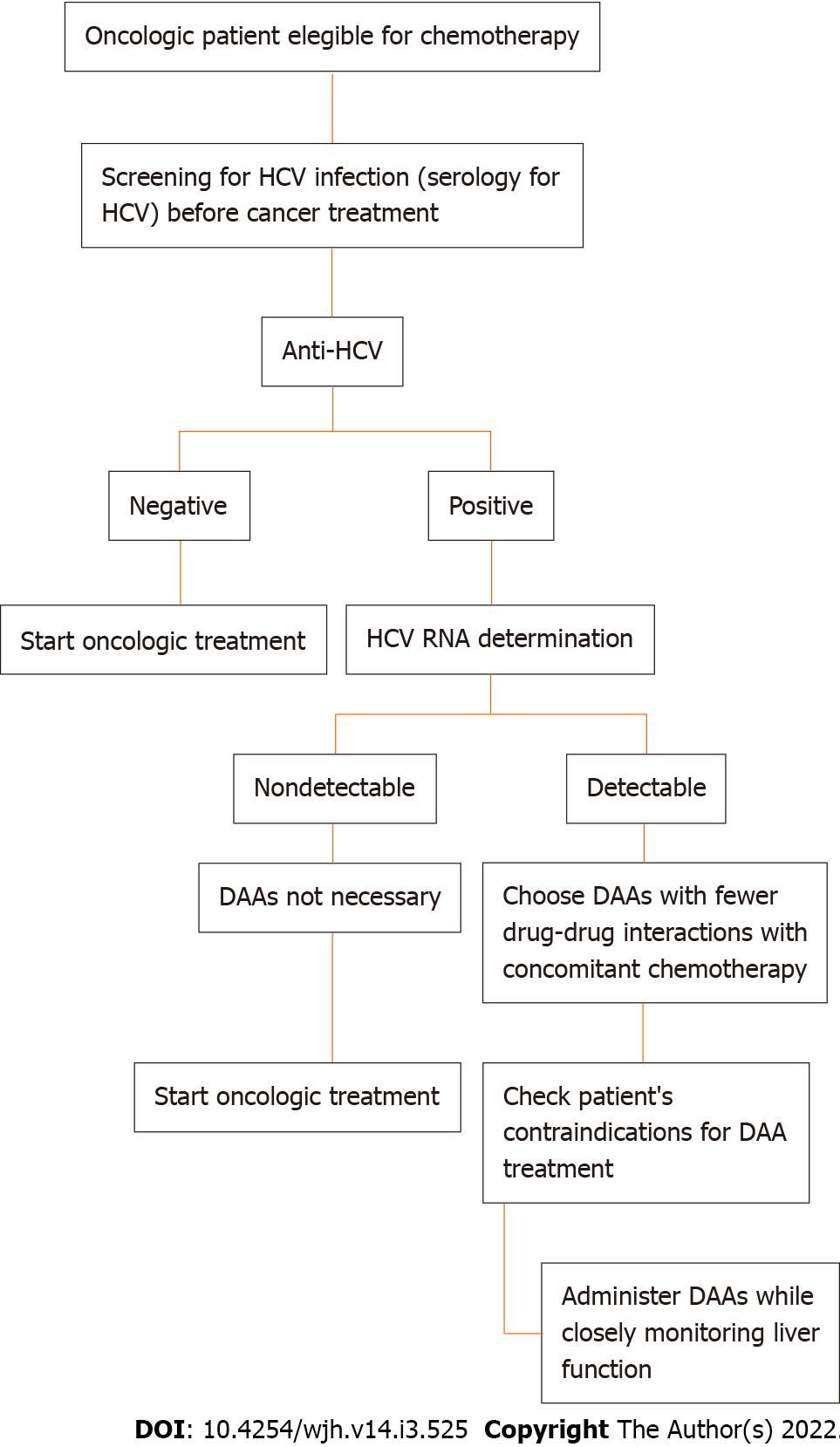

According to Rung Li et al[11], HCV reactivation (HCVr) in an oncologic setting is promoted by immunosuppression due to chemotherapy, often resulting in deleterious changes in the cancer treatment plan and its outcomes. HCVr prevalence rates in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy range from 1.5% to 32% worldwide[12]. Although less fearful than HBV reactivation, HCVr is challenging for oncologists and HCV treating physicians, who often avoid administering antiviral treatment to patients under chemotherapy because of a lack of data about the safety of this treatment combination[12,10]. The multicentre, prospective cohort study performed by Ramsey and colleagues[13] among more than 5000 new oncologic patients found an observed infection rate of 2.4% (95%CI: 1.9% to 3.0%) for HCV, with a substantial proportion of patients being unaware of their viral status at the time of cancer diagnosis (31%) and having no identifiable related risk factors (32.4%). Finally, according to this cohort study, therapeutic decisions were changed in 8% of patients because of their viral status[4,13]. In an observational study conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center, an HCVr rate of 23% was estimated among patients with cancer (36% in haematologic and 10% in solid tumour settings), with a more frequent recurrence in patients with prolonged lymphopenia (median 95 vs 22 d, P < 0.001) and in patients receiving rituximab (44% vs 9%), bendamustine (22% vs 0%), high-dose steroids (57% vs 21%) and purine analogues (22% vs 5%). The study also showed an unanticipated discontinuation or dose reduction of chemotherapy for 26% (6 of 23) of oncologic patients with HCVr[4]. In both studies, it was concluded that the early identification and treatment of chronic HCV hepatitis prevent HCVr after iatrogenic immunodepression and the remodulation of chemotherapy itself. Thus, screening for HCV infection before cancer treatment appears to be useful and advisable. Figure 1 shows an HCV screening recommendation flowchart for oncologic patients eligible for chemotherapy.

HCV infection therapeutic strategies have changed over time[2]. The first therapeutic combination employed against HCV infection in 1990 was based on interferon (IFN) plus ribavirin, which was associated with suboptimal response rates and short- and long-term toxicity even related to drug-to-drug interactions with other medications taken[14]. Moreover, because of intrinsic contraindications for each element of the compound, patients with unbalanced mood unbalanced or anaemia were excluded from the treatment[14]. The first direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), boceprevir and telaprevir, were approved in 2011; since then, the HCV cure rates have markedly improved, and they have been added to the classic dual therapy represented by IFN + ribavirin[15]. After the introduction of the combined regimens based on glecaprevir/pibrentasvir [Glecaprevir (GLE)/Pibrentasvir (PIB)], sofos

| Trade name | Compound | Year of FDA/EMA approval | Mechanism of action | Pharmaceutical form | Dose | Genotypes |

| Zepatier | Elbasvir/grazoprevir | 2016 | NS5A inhibitor/protease inhibitor | Film-coated tablet | 50 mg/100 mg qd | 1a, 1b, 4 |

| Epclusa | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir | 2016 | NS5B inhibitor/ NS5A inhibitor | Film-coated tablet | 400 mg/100 mg | Pangenotypic |

| Maviret | Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir | 2017 | Protease inhibitor/NS5A inhibitor | Film-coated tablet | 100 mg/40 mg qd | Pangenotypic |

| Vosevi | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir | 2018/2017 | NS5B inhibitor /NS5A inhibitor/protease inhibitor | Film-coated tablet | 400 mg/100 mg/100 mg | Pangenotypic |

In relation to the pharmacokinetic characteristics of currently used DAAs, the time to maximal plasma concentration (tmax), maximal plasma concentration (cmax), area under the concentration time curve (AUC) and minimal plasma concentration (cmin) are considered with regard to absorption, while the apparent volume of distribution (Vd/L) and percentage of protein binding are considered in relation to distribution. Metabolism is described in terms of the type of substrate elicited by DAAs and excretion as the elimination half-life (T ½)[1].

The pharmacokinetic characteristics of currently used DAAs are summarized in Table 2.

| DAAs | Absorption | Distribution | Metabolism | Excretion | |||||

| Tradename | Compound | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | Cmin (ng/mL) | AUC (ng∙h/mL) | Vd/F | Protein binding (%) | Substrate of | T ½, (h) |

| Zepatier | Elbasvir | 3 | 121 | 48.4 | 1920 | 680 | > 99.9 | P-gp | 31 |

| Grazoprevir | 2 | 165 | 18.0 | 1420 | 1250 | > 98.8 | P-gp | 24 | |

| Epclusa | Sofosbuvir | 0.5-1/3 | 566/868 | NR | 1260/13970 | NR | 61-65 minim | P-gp and BCRP | 0.5/25 |

| Velpatasvir | 4 | 311 | NR | 2970 | NR | > 99.5 | P-gp, OATP1B, and BCRP | 15 | |

| Maviret | Glecaprevir | 5.0 | 597 | NR | 4800 | NR | 97 | P-gp | 6-9 |

| Pibrentasvir | 5.0 | 110 | NR | 1430 | NR | > 99.9 | P-gp | 23-29 | |

| Vosevi | Sofosbuvir | 2/4 | 678/744 | NR | 1665/12,834 | NR | 61-65 minim | P-gp and BCRP | 0.5/29 |

| Velpatasvir | 4 | 311 | NR | 4041 | NR | > 99 | P-gp, OATP1B1/3, and BCRP | 17 | |

| Voxilaprevir | 4 | 192 | 47 | 2577 | NR | > 99 | P-gp and BCRP | 33 | |

Absorption: EBR is a substrate of P-gp, with a median tmax of 3 h and a range of 3-6 h. The bioavailability is estimated approximately 32%. Absorption (AUC 11% and Cmax 15%) can be decreased by a high-fat meal (900 kcal; 500 kcal fat). GZR acts as a substrate for P-gp and has a median tmax of 2 h with a range of 0.5-3 h. The absolute bioavailability varies from 15 to 27% after a single dose and from 20 to 40% after multiple doses. Absorption (AUC 50% and Cmax 108%) can be increased by a high-fat meal (900 kcal; 500 kcal fat). HCV-infected patients have increased exposure (approximately 2-fold) compared with healthy individuals. Steady state is reached at approximately the sixth day of administration[21,22].

Distribution: EBR and GZR are highly bound to albumin for > 99.9% and to α1-acid glycoprotein for > 98.8%[23,24]. The estimated Vd/L values for EBR and GZR are 680 and 1250 L, respectively. The hepatic transporter OATP1B1/3 actively transports GZR[25]. EBR inhibits P-gp. EBR and GZR inhibit BCRP[21,22].

Metabolism: EBR and GZR are metabolized by CYP3A4, but no circulating metabolites can be found in plasma. CYP3A4 is weakly inhibited by GZR[21,22].

Excretion: EBR and GZR are excreted mainly by liver; more than 99% of the excreted dose can be found in faeces. The apparent t1⁄2 of EBR and GZR is 24 and 31 h[21,22].

Absorption: The SOF Cmax after administration is 0.5-1 h. The AUC∞ of SOF can be increased by 60% and 78% by a moderate- and high-fat meal, respectively. However, the SOF Cmax is not affected by food[23,24]. The VEL median tmax is estimated around 3 h, while the AUC and Cmax values are lower in healthy volunteers (41% and 37%), when compared to those of HCV-infected subjects. The AUC of VEL can be increased after a moderate- (600 kcal; 30% fat) and high-fat (800 kcal; 50% fat) meals, while the Cmax increases by only 34% and 5%, respectively. The solubility of VEL is pH-dependent: In fact the increase of pH determines a reduction in solubility and absorption[23,24].

Distribution: Circulation proteins highly protein bind VEL (> 99.5%), regardless of the concentration range 0.09-1.8 μg/mL of the drug. SOF acts as a substrate of BCRP and P-gp. VEL acts as a substrate of BCRP, P-gp and OATP1B[25,26]. Plasma proteins that are not dose-dependent (1-20 μg/mL) bind SOF at 61%-65%[23,24].

Metabolism: VEL is metabolized by CYP2B6, CYP2C8, and CYP3A4, but > 98% of the parent drug can be found in the blood after a single dose. VEL inhibits P-gp, BCRP, and OATP1B1/3[23,24]. Refers to the SOF/VEL/VOX paragraph for SOF metabolism.

Excretion: The clearance of VEL is mainly hepatic, VEL is retrieved in faeces for > 94% and in urine for 0.4%. The t1⁄2 of VEL is approximately 15 h[25,26]. SOF is mainly excreted by kidneys (80%) as GS-331007 (78%). The t1⁄2 of SOF is 0.5 h, while the t1⁄2 of GS-331007 is 25 h[23,24].

Absorption: The tmax of GLE/PIB is about 5 h. Fat meals (moderate and high) can increase the absorption of GLE/PIB: The exposure of GLE after a meal is increased 83%-163% and the exposure of PIB is increased 40%-53%. Both drugs are P-gp substrates[25,26].

Distribution: Plasma proteins highly bind 97.5% to GLE and > 99.9% to PIB, both of drugs are actively transported by BCRP. GLE constitutes also a substrate of OATP1B1/3[25,26].

Metabolism: GLE is metabolized by CYP3A4, and PIB does not undergo biotransformation[25,26].

Excretion: GLE is primarily excreted by the liver; in fact, 92.1% of a radioactive dose is retrieved in faeces. The t1⁄2 is 6-9 h at steady state. PIB is also primarily found in stool (96.6%), with a t1⁄2 of 23–29 h[25,26].

Absorption: The Cmax of VOX, VEL, and a major metabolite of SOF, namely, GS-331007 is reached after approximately 4 h; the Cmax of SOF is reached after 2 h. The AUC and Cmax of VEL are 41% and 39% decreased in patients, respectively, while the AUC and Cmax of VOX are both elevated by 260% when comparing HCV-infected individuals and healthy volunteers[27,28]. The AUC∞ and Cmax of SOF increasefrom 64 to 114% and 9% to 76%, respectively, after a meal. The Cmax of GS-331007 after a meal decreases (19%-35%). The AUC∞ and Cmax of VEL increase (40%-166% and 37%-187%, respectively). The AUC of VOX increases from 112% to 435%, while the Cmax of VOX increases from 147% to 680%[27,28].

Distribution: Plasma proteins highly bind to SOF, VEL, and VOX (61%-65%, > 99%, and > 99%, respectively), with a concentration independent pharmacokinetics (ranging from 1 to 20 and 0.09 to 1.8 μg/mL, respectively) for SOF and VEL. SOF acts as a substrate of P-gp and BCRP, while VEL acts as a substrate of P-gp, OATP1B1/3, and BCRP. Finally, VOX acts as a substrate of P-gp and BCRP[27,28].

Metabolism: VOX is a substrate of CYP3A4. VOX is an inhibitor of P-gp, BCRP, and OATP1B1/3[27,28]. The metabolism of SOF and VEL is reported in the paragraph on SOF/VEL combination therapy above.

Excretion: SOF is excreted by the kidneys (80%), mainly in the form of GS-331007 (78%). The t1⁄2 of SOF is 0.5 h and the t1⁄2 of GS-331007 is 29 h[28,29]. The clearance of VEL is mainly hepatic. The t1⁄2 of VEL is approximately 17 h (27). The excretion is mainly biliary[27,28].

Intended as the balance between the effect (reduction of HCV-RNA under therapy) and toxicity (adverse effects), the pharmacodynamics of currently used DAAs consist of the duration of therapy, safety profile and estimated adverse effects.

EBR/GZR is efficacious for subjects affected by genotypes 1 and 4 HCV infection treated for 12 wk. EBR/GZR is approved for patients with renal insufficiency and compensated cirrhosis. This combination is approved in the fixed dose combination of 50 mg/100 mg once daily. The favourable safety profile with low discontinuation rates (< 5%) makes this compound suitable for HCV-infected patients with genotypes 1 and 4. The most frequent adverse effects are fatigue, headache, asthenia, nausea, rash, and an increase in ALT/AST and ALP[1,21].

SOF/VEL combination for 12 wk is valid in HCV pangenotypic patients treatment-experienced and/or treatment-naïve. Mild described adverse events are headache, fatigue, nausea and insomnia. Combination therapy with ribavirin leads to anaemia in over 10% of patients[1,24].

GLE/PIB is a pangenotypic regimen that is highly effective when administered for 8 to 12 wk once daily at doses of 100 mg/40 mg. Naïve and experienced patients with or without cirrhosis can be treated with this compound, whichhas a mild toxicity profile, in which headache, fatigue, nasopharyngitis and nausea can arise[1,25].

Finally, the pangenotypic highly effective SOF/VEL/VOX combination is licenced for patients who fail to respond to IFN/riba and DAAs and those with or without compensated cirrhosis. The adverse effects described are headache, diarrhoea, fatigue, nausea and constipation[1,27].

The pharmacodynamic properties of currently used DAAs are summarized in Table 3.

| Trade name | Compound | Efficacy | Toxicity |

| Zepatier | Elbasvir/grazoprevir | Effective regimen used for 12 wk against HCV genotype 1 and 4. Approved for patients with renal insufficiency and compensated cirrhosis. Fixed dose combination of 50 mg/100 mg once daily. Favourable safety profile with low discontinuation rates (< 5%) | Fatigue, headache, asthenia, nausea, rash, ALT/AST and ALP increase |

| Epclusa | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir | Treatment for 12 wk highly effective in both treatment-experienced and treatment-naïve HCV pangenotypic patients | Fatigue, headache, nausea and insomnia. Combination therapy with ribavirin led to anaemia in over 10% of patients |

| Maviret | Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir | Pangenotypic highly effective regimen. Administered for 8 to 12 wk once daily at doses of 100 mg/40 mg. Naïve and experienced patients with or without cirrhosis | Headache, fatigue, nasopharyngitis and nausea |

| Vosevi | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir | Pangenotypic, highly effective, licenced for patients in whom IFN/riba and DAAs failed | Headache, diarrhoea, fatigue, nausea and constipation |

Drug-drug interactions are challenging in the course of cotreatment with chemo

| Chemotherapy drug classes | Examples |

| Platinum-containing agents | (Cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin) |

| Folate antagonists | (Methotrexate, pemetrexed) |

| Pyrimidine compounds | (Fluorouracil, capecitabine, cytarabine, gemcitabine, decitabine) |

| Purine analogues | (Mercaptopurine, fludarabine, cladribine, clofarabine) |

| Alkylating agents | (Cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, melphalan, bendamustine, busulfan) |

| Anthracyclines | (Daunorubicin, doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin, bleomycin) |

| Topoisomerases | (Topotecan, etoposide, irinotecan) |

| Cytidine analogues | (Azacytidine, decitabine) |

| Immunosuppressants | (Tacrolimus, cyclosporine) |

| Immunomodulatory drugs | (Ienalidomide, thalidomide) |

| Mitotic inhibitors | (Paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine, vincristine) |

| Hormonal therapies | (Tamoxifen) |

| Targeted therapies other than rituximab | (e.g., cetuximab, bortezomib, alemtuzumab) |

According to the Liverpool HEP chart, drugs that absolutely should not be coadministered (RED interactions) are as follows: Elbasvir/grazoprevir + immunosuppressants (cyclosporine): Concomitant use of elbasvir/grazoprevir with OATP1B inhibitors, such as cyclosporine, is contraindicated. The coadministration of multiple doses of elbasvir/grazoprevir and a single dose of cyclosporin increases the grazoprevir AUC by 15-fold. The risk of ALT elevations may be increased due to the significant increase in grazoprevir plasma concentrations caused by OATP1B1/3 inhibition[29].

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir + folate antagonists (methotrexate): Coadministration has not been studied but would not be recommended due to increased exposure tomethotrexate due to BCRP inhibition by voxilaprevir[29]. Sofos

According to the Liverpool HEP chart, potential clinically significant interactions-likely to require additional monitoring and an alteration of drug dosage or the timing of administration (AMBER interactions)-are described among the following: Elbasvir/grazoprevir + folate antagonists (methotrexate): Coadministration has not been studied. Methotrexate is a substrate of BCRP, and concentrations could increase due to inhibition by elbasvir/grazoprevir. No a priori dose alteration is recommended, but patients should be closely monitored[29]. Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir + folate antagonists (methotrexate): Coadministration has not been studied. Methotrexate is a substrate of BCRP, and concentrations may increase due to inhibition by sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Although no a priori dose alteration is required, close monitoring is recommended[29]. Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir + immunosuppressants (cyclosporine): Concomitant use of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir with cyclosporine requires close monitoring of doses, as concentrations of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir may increase due to the inhibition of OATP1B. The coadministration of gleca

According to the Liverpool HEP chart, potentially weak interactions-for which additional action/monitoring or dosage adjustment is unlikely to be required (YELLOW interactions)-are described among the following: Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir + hormonal therapies (tamoxifen): Coadministration has not been studied. Tamoxifen is mainly metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, which are not affected by sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. However, tamoxifen induces CYP3A4 and could potentially decrease the concentrations of velpatasvir, although to a moderate extent. Coadministration with food is suggested if tamoxifen is coadministered with sofos

Some comedications with a green classification may require dose adjustment due to hepatic impairment.

HCV-infected oncologic patients represent a special population needing guided treatment[12]: The updated guidelines provided by the AASL and IDSA[4] for the first time address treatment in this setting, supporting that the virologic and hepatic benefits of DAA treatment in oncologic patients with HCV infection overcome the risk of no treatment[7,30,31]. In fact, the quick eradication of chronic HCV infection prior to cancer therapy helps liver recovery, normalizes liver enzymes and avoids potentially decompensating hepatitis flares; in other words, it allows the initiation of cancer treatment that could be hampered by persistent elevated ALT levels due to HCV virus infection[12]. The eradication of HCV in oncologic patients can also diminish the risk of HCVr, allow patients to participate in experimental oncologic clinical trials based on new drug strategies against cancer, reduce the risk of the development of HCV-associated cancers[4], minimize drug-induced hepatotoxicity and avoid detrimental dose reduction.

DAA-based therapy can also promote liver disease progression[12]. In clinical practice, the temporary suspension of cancer treatment during DAA-based therapy has often been observed to avoid overlapping toxicities and DDIs. However, the present review proves that when cancer treatment cannot be interrupted, currently used DAAs can be simultaneously administered under close comonitoring by oncologists and hepatologists, especially during the first month of this dual therapy, since serious observed adverse events most usually appear within the first 2-4 wk of concomitant treatment.

Economides et al[12] stated that DAA therapy in cancer patients was efficacious and durable in terms of SVR, and few drug-drug interactions were observed. Otherwise, prospective data on HCV in oncologic patients remain limited.

This review, in the absence of current specific available guidelines for the use of DAA therapy in HCV-infected cancer patients, tried to clarify that treatment with DAAs for oncologic patients undergoing chemotherapy affected by HCV infection is safe and favourably impacts oncologic outcomes.

Finally, given that cancer treatment can negatively impact untreated chronic HCV-related liver disease, it appears clear that pre-emptive antiviral therapy in the oncologic setting is necessary to pursue chemotherapy without risking the progression of viral liver disease.

| 1. | Smolders EJ, Jansen AME, Ter Horst PGJ, Rockstroh J, Back DJ, Burger DM. Viral Hepatitis C Therapy: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations: A 2019 Update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:1237-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gao LH, Nie QH, Zhao XT. Drug-Drug Interactions of Newly Approved Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents in Patients with Hepatitis C. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:289-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hepatitis C – World Health Organization. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c. |

| 4. | Ziogas DC, Kostantinou F, Cholongitas E, Anastasopoulou A, Diamantopoulos P, Haanen J, Gogas H. Reconsidering the management of patients with cancer with viral hepatitis in the era of immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hwang JP, LoConte NK, Rice JP, Foxhall LE, Sturgis EM, Merrill JK, Torres HA, Bailey HH. Oncologic Implications of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:629-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1764] [Cited by in RCA: 1857] [Article Influence: 92.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Torres HA, Shigle TL, Hammoudi N, Link JT, Samaniego F, Kaseb A, Mallet V. The oncologic burden of hepatitis C virus infection: A clinical perspective. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:411-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mahale P, Sturgis EM, Tweardy DJ, Ariza-Heredia EJ, Torres HA. Association Between Hepatitis C Virus and Head and Neck Cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Balakrishnan M, Glover MT, Kanwal F. Hepatitis C and Risk of Nonhepatic Malignancies. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:543-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Torres HA, Hosry J, Mahale P, Economides MP, Jiang Y, Lok AS. Hepatitis C virus reactivation in patients receiving cancer treatment: A prospective observational study. Hepatology. 2018;67:36-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li YR, Hu TH, Chen WC, Hsu PI, Chen HC. Screening and prevention of hepatitis C virus reactivation during chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5181-5188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Economides MP, Mahale P, Kyvernitakis A, Turturro F, Kantarjian H, Naing A, Hosry J, Shigle TL, Kaseb A, Torres HA. Concomitant use of direct-acting antivirals and chemotherapy in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1235-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ramsey SD, Unger JM, Baker LH, Little RF, Loomba R, Hwang JP, Chugh R, Konerman MA, Arnold K, Menter AR, Thomas E, Michels RM, Jorgensen CW, Burton GV, Bhadkamkar NA, Hershman DL. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis C Virus, and HIV Infection Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer From Academic and Community Oncology Practices. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:497-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ghany MG, Liang TJ. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:679-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Strader DB, Seeff LB. A brief history of the treatment of viral hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2012;1:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Smith BD, Jorgensen C, Zibbell JE, Beckett GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiatives to prevent hepatitis C virus infection: a selective update. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 Suppl 1:S49-S53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Garrison KL, German P, Mogalian E, Mathias A. The Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of Antiviral Agents for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46:1212-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chahine EB, Kelley D, Childs-Kean LM. Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir: A Pan-Genotypic Direct-Acting Antiviral Combination for Hepatitis C. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:352-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Karaoui LR, Mansour H, Chahine EB. Elbasvir-grazoprevir: A new direct-acting antiviral combination for hepatitis C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1533-1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yao Y, Yue M, Wang J, Chen H, Liu M, Zang F, Li J, Zhang Y, Huang P, Yu R. Grazoprevir and Elbasvir in Patients with Genotype 1 Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Comprehensive Efficacy and Safety Analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:8186275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics: Zepatier. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/zepatier-epar-product-information_en.pdf. |

| 22. | US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: Zepatier. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/Label/2017/208261s002Lbl.pdf. |

| 23. | European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics: Epclusa [in Dutch]. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/epclusa-epar-product-information_nl.pdf. |

| 24. | US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: Epclusa. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/Label/2017/208341s007Lbl.pdf. |

| 25. | European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics: Maviret 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/maviret-epar-product-information_nl.pdf. |

| 26. | US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: Maviret. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/Label/2017/209394s000Lbl.pdf. |

| 27. | European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics: Vosevi. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/vosevi-epar-product-information_en.pdf. |

| 28. | US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: Vosevi. 2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/Label/2017/209195s000Lbl.pdf. |

| 29. | DAAs-chemotherapies drug-drug interactions according to Liverpool Drug Interactions Group, University of Liverpool, Pharmacology Research Labs, 1st Floor Block H, 70 Pembroke Place, LIVERPOOL, L69 3GF. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.hep-druginteractions.org. |

| 30. | Torres HA, Pundhir P, Mallet V. Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Patients With Cancer: Impact on Clinical Trial Enrollment, Selection of Therapy, and Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:909-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | AASLD-IDSA. Hcv guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Accessed 16 Nov 2021. Available from: https://www.Hcvguidelines.Org. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Negro F, Sira AM S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH