Published online Dec 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i12.2192

Peer-review started: June 11, 2021

First decision: July 27, 2021

Revised: July 29, 2021

Accepted: October 27, 2021

Article in press: October 27, 2021

Published online: December 27, 2021

Processing time: 198 Days and 19.8 Hours

Primary liver teratoma is an extremely rare tumor usually affecting children under the age of 3 years. Specific signs of teratoma on ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging are lacking, which makes morphology the only diagnostic tool. Misdiagnosis of a mature teratoma may lead to excessive liver resection, whereas misdiagnosis of an immature teratoma may result in spread, causing a life-threatening condition. Consequently, a careful tumor examination is important, and the rarest types of tumors must be accounted for.

We describe a 52 years old female who presented with a solid mass in the left liver lobe. Contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a round, heterogeneous lesion containing a number of fluid areas and areas of calcification in the middle, and the provisional diagnosis was cholangiocarcinoma. The patient underwent resection of liver segment I. Immunohistochemistry analysis of the resected lesion indicated thyroid follicular epithelium; however, the thyroid gland was intact. 10 years prior to presentation the patient underwent a surgery due to mature teratoma of the right ovary, nevertheless the tumor was benign and could not spread to the liver, in addition teratoma of the liver was also benign. This led to the final diagnosis of primary mature liver teratoma.

Primary hepatic teratoma, including heterotopia of the thyroid gland in the liver, is an extremely rare condition in adults that needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of solid-cystic neoplasms in the liver and cholangiocarcinoma. This case adds to the limited literature on the patient presentation, clinical workup and management of liver teratomas.

Core Tip: Primary liver teratoma is an extremely rare tumor. This condition in adults needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of solid-cystic neoplasms in the liver and cholangiocarcinoma. A careful tumor examination is important, and the rarest types of tumors must be accounted for to allow the diagnosis of heterotopia of the thyroid gland in the liver.

- Citation: Kovalenko YA, Zharikov YO, Kiseleva YV, Goncharov AB, Shevchenko TV, Gurmikov BN, Kalinin DV, Zhao AV. Rare primary mature teratoma of the liver: A case report. World J Hepatol 2021; 13(12): 2192-2200

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v13/i12/2192.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i12.2192

Teratoma is a rare germ cell tumor (GCT) that comprises at least two of three germ cell layers, the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, and affects both children and adults. Teratomas primarily affect gonadal tissues, as the origin of these tumors is primordial germ cells, which migrate from the allantois to the fetal gonads during the first week of fetal life[1]. Thus, teratomas may also occur along the migration path of primordial germ cells, which can remain in midline extragonadal sites[2]. Consequently, the liver is an extremely rare site for primary teratomas, with an incidence of approximately 1% of all teratomas. Most patients with hepatic teratoma are children under the age of 3 years[3]. Nevertheless, primary or secondary teratomas of the liver can lead to serious health issues and can be a life-threatening condition that claims a comprehensive diagnosis and well-timed therapy. Therefore, our case report and review aim to collect scarce information about hepatic teratomas.

Depending on the differentiation degree of their components, teratomas are classified as mature and immature[1]. Immature teratomas have a tendency for rapid growth, malignant transformation, and metastasis within adults; therefore, the prognosis is very poor[2].

Mature teratomas can be cystic, solid and mixed. According to the reported cases, cystic teratomas of the liver are the most common within mature teratomas. Mature cystic teratomas of the liver represent a mostly unilocular cystic cavity that may have septation and/or calcification and comprise mature elements derived from 3 cell layers, such as thyroid tissue, tooth enamel, hairs, skin, bone, fat, cartilage, neural tissue, or epithelium. The most commonly mature cystic teratomas affect the ovaries; however, approximately 1% of these lesions are found in the liver, usually within females in the right liver lobe[4-6]. The shape and size of mature cystic teratomas on gross appearance are not unique and vary significantly; thus, the largest reported lesion dimensions were 21 cm× 18 cm× 12 cm, and the weight was 1837 g[7]. The symptoms of mature cystic liver teratoma are nonspecific and conditioned by mechanical pressure of the growing tumor, including abdominal distension, constipation, fever, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, a sense of fullness in the right upper quadrant, vomiting, etc.[3,8]. Cases of asymptomatic mature teratoma have also been reported[9,10]. Rahmat et al[11] described a 46 years old male who presented with cholangitis caused by a primary benign teratoma of the liver measuring 5.0 cm x 6.5 cm x 8.0 cm and compressing a common bile duct. Despite their high degree of differentiation, cystic teratomas can transform to malignant tumors and harbor other neoplasms; therefore, complete surgical removal is an optimal treatment that can be followed by chemotherapy if necessary[5,12]. Recently, Ramkumar et al[13] reported a case of a primary mature teratoma rupture accompanied by acute abdominal pain in a 65 years old female. Surgical removal of the tumor was performed after liquid and antibiotic therapy, and areas of necrosis and hemorrhage were found on histopa

The differentiation degree of the components of immature teratomas is low, and these tumors may involve any type of tissue, although neurogenic elements are the most common. On histopathology, these teratomas can also be divided into predominantly cystic, solid, and solid with multiple cysts and may contain areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Immature teratomas tend to show rapid growth with liver capsule invasion and metastasis[2]. Primary immature hepatic teratomas are extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 3 case reports have been published in the English literature up to 2021. The liver is also a rare site of teratoma metastasis; however, secondary immature teratomas are more frequent[14,15]. The symptoms of immature liver teratoma have been described in a few case reports and include pain and sensation of fullness in the right upper quadrant, fatigue, sweating, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss[2,16]. Malek-Hosseini et al[16] reported the largest immature liver teratoma, measuring 27 cm in diameter, and the patient recovered completely through surgery with a good follow-up. Immature liver teratomas lead to an elevation in AFP levels, whereas mature teratomas cannot produce AFP; thus, AFP is usually utilized for the differential diagnosis; nevertheless, AFP elevation does not necessarily occur[14,17]. The treatment of immature teratomas includes adjuvant chemotherapy and complete resection of the primary tumor and every metastasis whenever possible[18]. Nonresectable hepatic teratomas require liver transplantation[19].

The main diagnostic tools for liver teratoma detection are contrast-enhanced CT and MRI, which can show the size, shape, and structure of the tumor and its position related to adjacent elements and organs. CT scans can reveal areas of calcification in teratomas, whereas MRI scans are not sensitive to calcium[3]. Cho et al[20] revealed the high sensitivity of attenuation correction CT (AC-CT) acquired during 18F-FDG PET-CT in the diagnosis of immature ovarian teratomas, as their components show significant 18F-FDG uptake. Thus, 18F-FDG PET-CT may be a useful diagnostic tool[20]. Serum AFP, LDH, hCG, CEA, and liver enzymes may be elevated in some patients[2]. However, the final diagnosis of teratoma can be made based only on the histopathology of the tumor samples[9].

Teratomas are usually treated with surgery and chemotherapy. However, metastatic teratomas of nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs) may not respond to chemotherapy and become significantly enlarged even after the original tumor is removed and serum tumor markers (AFP, beta-HCG) and LDH return to normal. This condition is known as growing teratoma syndrome (GTS). This syndrome is uncommon, and its etiology and pathogenesis are still unclear; consequently, the diagnosis may be delayed, and the patient's prognosis may become poor[21]. There are two dominant theories on the pathogenesis of GTS: (1) Chemotherapy leads to the survival and subsequent thriving of mature components, whereas immature components are highly sensible; and (2) Chemotherapy results in DNA damage and transformation of the immature teratoma to a mature teratoma[22]. Hiester et al[23] suggested a model of GTS development, according to which these tumors comprise meroclones derived from holoclones under chemotherapy. The authors termed these cells “teratoma-forming transit-amplifying cells (TF-TACs)”[23].

GTS should be suspected in every patient with a growing tumor and normal tumor marker levels after chemotherapy of the original NSGCT[21]. The most common sites of original NSGCTs are the ovaries and testis, whereas metastasis usually affects the retroperitoneum; nevertheless, cases of GTS from liver metastasis have also been reported. The common features of the described patients included young age (22 and 24 years old), multiple metastatic deposits among the entire liver, retroperitoneal lymph nodes and kidney from testicular tumors, and elevated AFP levels. Interestingly, the liver teratomas were mature, and there was no evidence of malignancy. Both patients underwent radical orchiectomy, nephrectomy, retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy and chemotherapy, and AFP levels returned to normal. However, the liver teratomas continued to grow, confirming the GTS diagnosis, and patients were accepted for liver transplantation (LT). After LT, there was no evidence of teratoma recurrence[24,25]. O’Reilly et al[22] presented the first case of GTS in a primary liver teratoma in a 22 years old female. AFP levels were elevated (over 18000 cm before chemotherapy) and significantly decreased thereafter, whereas the tumor continued to enlarge up to 31.4 cm x 25.4 cm x 42.1 cm, and GTS was suspected. The patient was discharged after right hepatectomy and resection of the right mediastinal and diaphragmatic metastases, and there was no evidence of teratoma recurrence after 18 mo[22]. Growing teratomas of the liver may cause a disturbance in vital function either by the mechanical compression of contiguous organs and vessels or by hepatic failure; moreover, the incidence of GTS-related malignancy is 2%-8%. As these tumors do not respond to chemo- or radiotherapy, such patients should undergo complete surgical removal of the teratomas, as incomplete resection has a higher rate of tumor recurrence[23].

A 52 years old woman was referred to our hospital by a specialist at the diagnostic center after a solid tumor was detected in the left lobe of the liver with ultrasound (US).

US revealed that the lesion measured 118 mm x 93 mm in size with sharp edges, a heterogeneous and hyperechoic parenchyma and areas of calcification. The patient did not have any complaints associated with this lesion.

The patient underwent right oophorectomy 10 years prior to presentation due to an epidermoid cyst (mature teratoma), and no chemo- or radiotherapy was assigned because the tumor was benign. Apart from that, the medical and family histories were unremarkable.

Personal and family history is not burdened.

During the general examination, no abnormalities were detected.

The laboratory assessment also did not reveal any pathological findings. The tumor markers CA 19-9 and AFP were not elevated (< 2.5 U/mL and 4.61 U/mL, respectively).

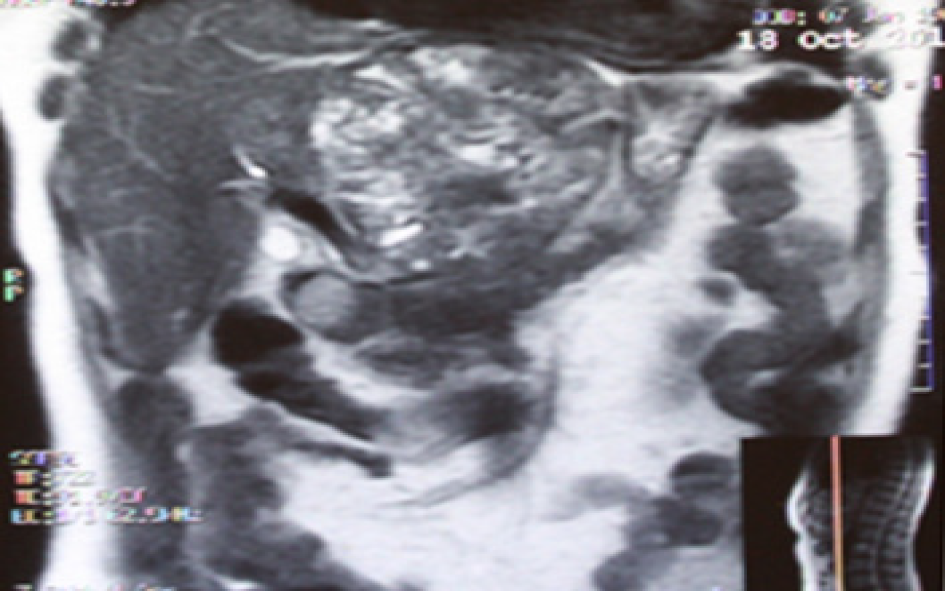

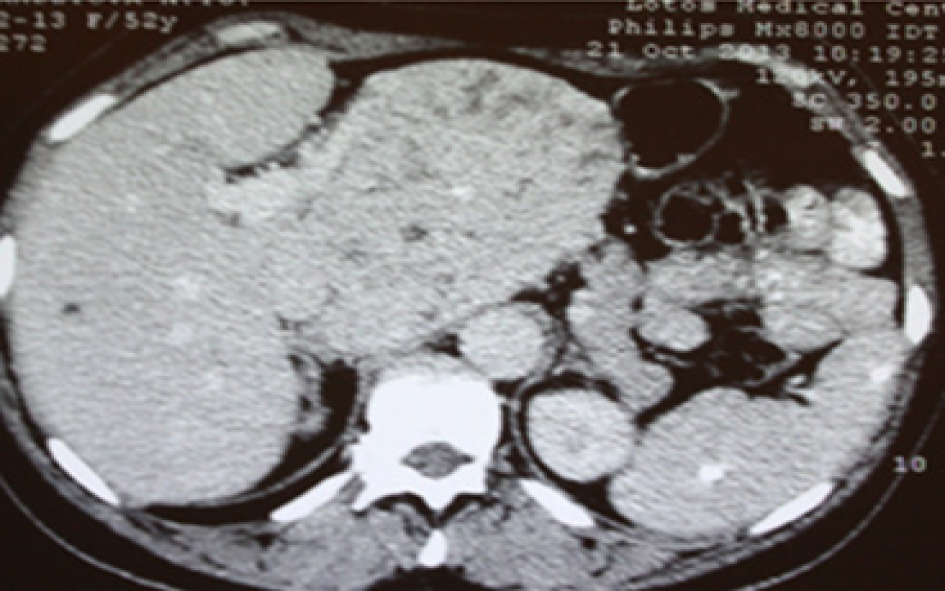

Subsequent US with color flow mapping (CFM) revealed moderate vascularization of the lesion and compression of the left portal vein, left hepatic artery and left hepatic vein. Subsequent CT and MRI revealed a heterogeneous lesion 111 mm x 109 mm x 97 mm in size with a round shape containing a number of fluid areas sized from 5 to 12 mm and areas of calcification in the middle of the tumor. The distal intrahepatic bile ducts were dilated, and the inferior vena cava was compressed (Figures 1 and 2). With reference to the CT and MRI scans, the provisional diagnosis was formulated as cholangiocarcinoma of the left hepatic lobe.

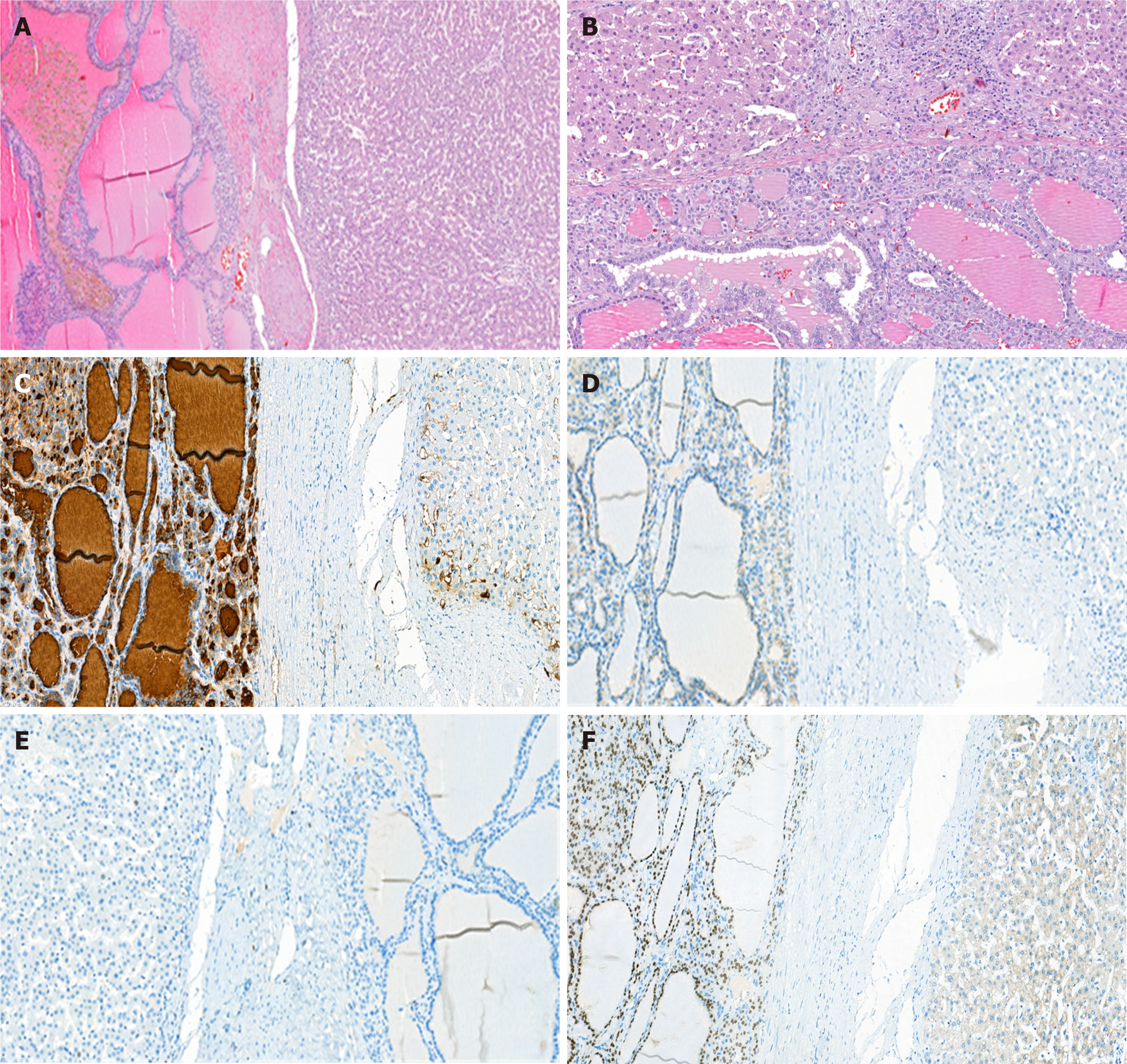

The histological examination suggested biliary hamartoma, but the lack of bilirubin in the cells lining the cavity did not allow us to exclude lymphangioma or follicular cancer (Figure 3). To reveal the true nature of the tumor and exclude a malignancy, immunohistochemical tests were performed. They demonstrated focal positive expression of thyroglobulin (clone 2H11+6 E1), TTF-1 (clone 8G7G3/1), and galectin-3 (clone 9C4), overexpression of cytokeratin 8 and 18 (clones B22.1 + B23.1) and negative expression of CD34 (clone QBEnd/10). The immunophenotype corresponded to the thyroid follicular epithelium. In the postoperative period, we performed ultrasonography, which did not show thyroid gland malignancy and the patient had no endocrine problems.

According to the gross appearing, histology and immunohistophenotype the ectopic thyroid gland in the liver (mature teratoma) was finally evident in the patient.

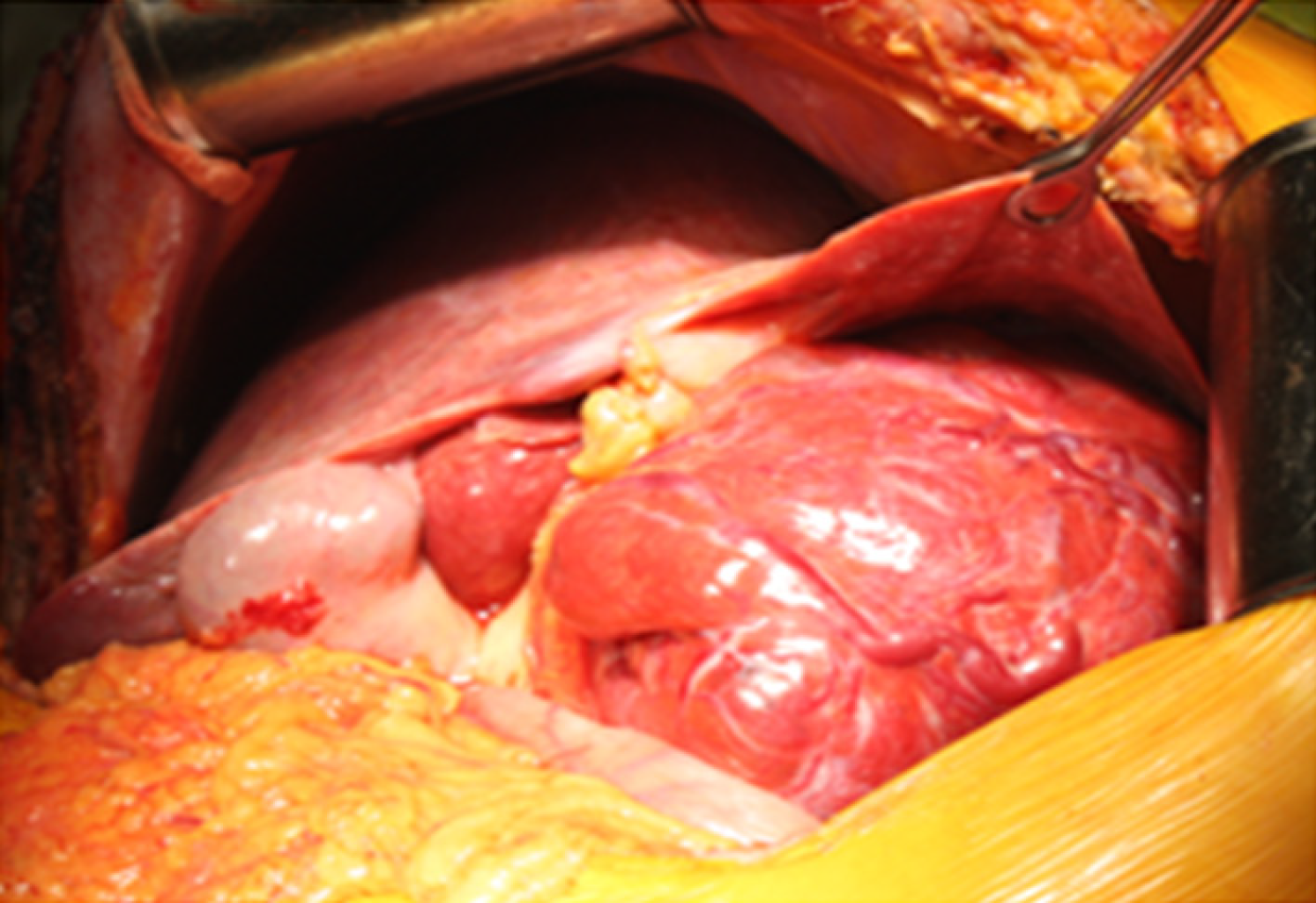

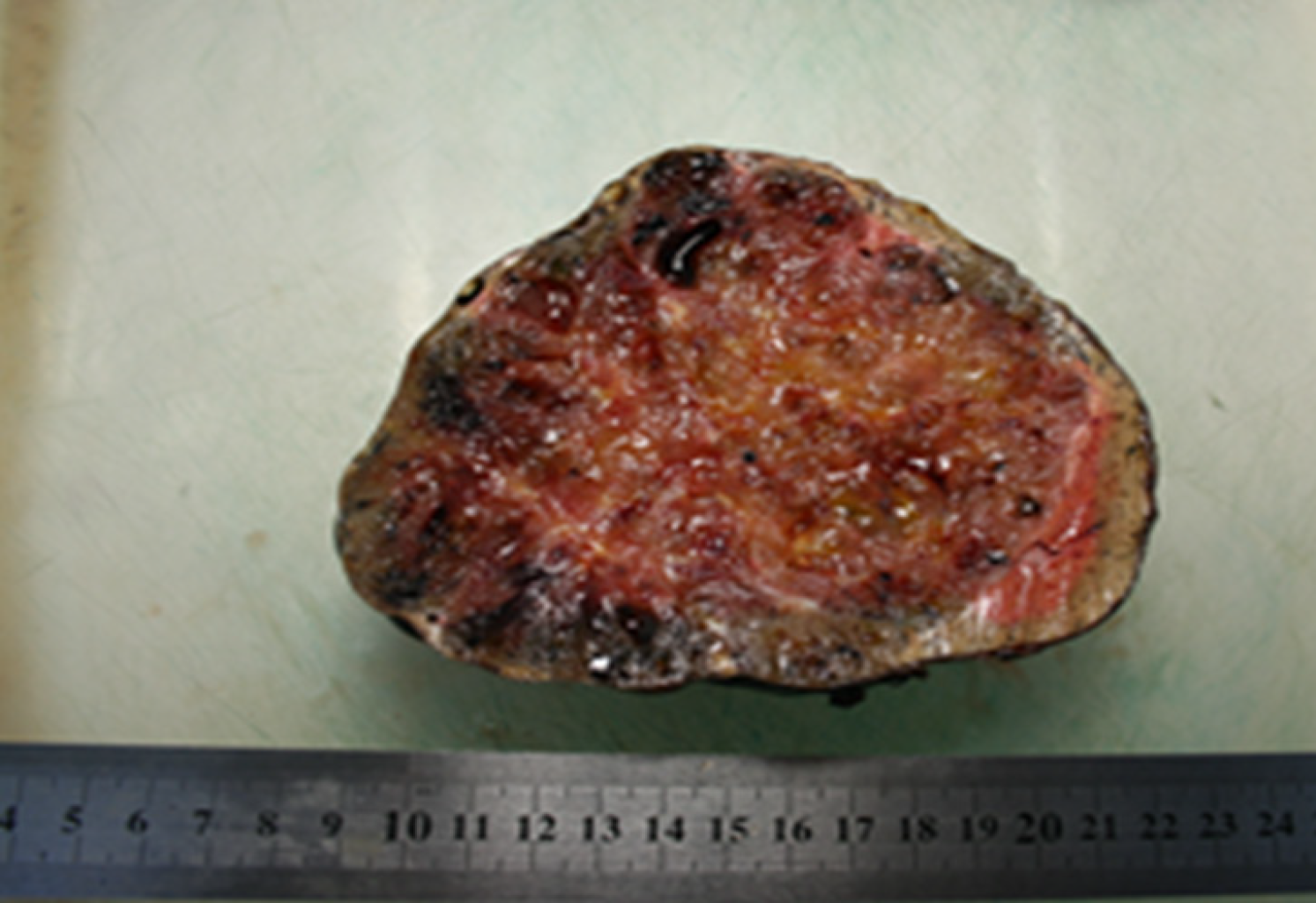

The patient underwent resection of segment I with the surrounding tumor hepatic parenchyma, D1 Lymphadenectomy and cholecystectomy. The intraoperative inspection revealed an increase in the left liver lobe due to the well-defined encapsulated inhomogeneous tumor in the first segment of the liver (14 cm х 13 cm х 13 cm), crushing atrophied segments 2 and 3 (Figures 4 and 5). The consistency of the tumor was soft, and on its surface, there were twisted veins.

The postoperative period was uneventful. Considering the benign nature of teratoma no complementary treatment was indicated. The patient was discharged from the hospital on the 8th day after the operation. Eight years after operation the patient has no complaints, no evidence of teratoma recurrence nor newly formed teratomas were revealed during CT examination in 2021.

Hepatic teratoma is rare; to the best of our knowledge, only a small number of case reports exist in the literature (Table 1), and no liver-specific treatment guidelines have been established[5]. The successful treatment of an ectopic thyroid gland in the liver, confirmed by morphological and immunohistochemical tests, described herein was very difficult to correctly diagnose preoperatively due to the highly variable instrumental visualization of the tumor and clinical manifestations of this disease. We managed to find only one similar case of hepatic teratoma in the reviewed literature[26].

| Ref. | Patient age | Diagnosis | Liver lobe | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Madan et al[8] | 34, female | Mature cystic teratoma | Right | Complete resection | Uneventful |

| Watanabe et al[27] | 20, female | N/A | Right | Complete resection | N/A |

| Winter et al[28] | 61, female | Mature Teratoma | Right | N/A | N/A |

| Martin et al[29] | 53, female | Mature cystic teratoma | Right | Complete resection | Uneventful |

| Nirmala et al[6] | 36, female | Mature teratoma | Right | Complete resection | Uneventful |

| O'Reilly et al[22] | 22, female | Immature teratoma | Right | Complete resection, chemotherapy | Uneventful |

| Certo et al[10] | 27, female | Mature teratoma | N/A | Complete resection | N/A |

| Jaklitsch et al[7] | 27, female | Mature cystic teratoma | N/A | Complete resection | Uneventful |

| Cöl et al[2] | 21, female | Immature teratoma | Right | Complete resection, chemotherapy | Recurrence, death |

| Xu et al[30] | 34, male | Immature teratoma | Right | Complete resection, chemotherapy | Recurrence, death |

| Han et al[31] | 46, male | Mature cystic teratoma | Quadrant | Complete resection | Uneventful |

The patient’s medical history provided no evidence of teratoma in thyroid gland tissue. Before the results of the morphological and immunohistochemical tests became available, the patient was considered to have perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Bearing in mind the state of our patient, we initially planned hepatectomy with a reconstruction biliary tract live-saving procedure.

The immunohistochemical test results demonstrated thyroid follicular epithelium as a result of the focal positive expression of thyroglobulin (clone 2H11+6 E1), TTF-1 (clone 8G7G3/1), and galectin-3 (clone 9C4), overexpression of cytokeratin 8 and 18 (clones B22.1 + B23.1) and negative expression of CD34 (clone QBEnd/10). This clinical case clearly demonstrates the diagnostic challenge of patients presenting with heterotopia of the thyroid gland in the liver simulating perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Only a comprehensive examination by clinical, biochemical, and radiological methods makes tumor detection possible and allows the identification of such rare conditions. The diagnostic challenges of this condition can be met with the mass-forming type of cholangiocarcinoma. A proper preoperative evaluation, surgical treatment and preparation facilitate positive treatment outcomes.

The patient underwent ovariectomy due to an epidermoid cyst (mature teratoma) of the right ovary 10 years prior to the detection of the hepatic tumor. Unfortunately, micrographs of the lesion were not available. The ovarian teratoma had no signs of malignancy; therefore, no chemotherapy or radiotherapy was indicated. Nevertheless, hepatic teratomas are not metastases from ovarian teratomas, as mature ovarian teratomas cannot spread. Hepatic teratoma is sometimes misdiagnosed as an immature ovarian teratoma if malignant; however, in the current case, the lesion had no signs of malignancy. Consequently, the patient was diagnosed with metachronous teratomas of the right ovary and liver.

In summary, we present an exceedingly rare clinical presentation of heterotopia of the thyroid gland in the liver in an adult patient who underwent surgical resection. The clinical workup included a CT scan, with confirmation of the diagnosis of hepatic teratoma on histopathology. Resection remains the mainstay of treatment.

Heterotopia of the thyroid gland in the liver is an extremely rare condition in adults that needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of solid-cystic neoplasms in the liver and cholangiocarcinoma. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of management, and risk stratification based on histology should determine postoperative surveillance. This case adds to the limited literature on the patient presentation, clinical workup, and management of liver teratomas.

| 1. | Peterson CM, Buckley C, Holley S, Menias CO. Teratomas: a multimodality review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2012;41:210-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cöl C. Immature teratoma in both mediastinum and liver of a 21-Year-old female patient. Acta Med Austriaca. 2003;30:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gupta R, Bansal K, Manchanda V, Gupta R. Mature cystic teratoma of liver. APSP J Case Rep. 2013;4:13. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ahmed A, Lotfollahzadeh S. Cystic teratoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2020. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564325/. |

| 5. | Krainev AA, Mathavan VK, Klink D, Fuentes RC, Birhiray R. Resection of a mature cystic teratoma of the liver harboring a carcinoid tumor. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nirmala V, Chopra P, Machado NO. An unusual adult hepatic teratoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:306-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jaklitsch M, Sobral M, deFigueiredo AAFP, Martins A, Marques HP. Rare giant: mature cystic teratoma in the liver. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Madan M, Arora R, Singh J, Kaur A. Mature cystic teratoma of the liver in an adult female. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:872-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Silva DS, Dominguez M, Silvestre F, Calhim I, Daniel J, Teixeira M, Ribeiro V, Davide J. Liver teratoma in an adult. Eur Surg. 2007;39:372-375. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Certo M, Franca M, Gomes M, Machado R. Liver teratoma. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2008;71:275-279. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Rahmat K, Vijayananthan A, Abdullah B, Amin S. Benign teratoma of the liver: a rare cause of cholangitis. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2006;2:e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SY, Jang MH, Koo YJ, Lee DH. Undifferentiated carcinoma arising in ovarian mature cystic teratoma: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020;13:1750-1754. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ramkumar J, Best A, Gurung A, Dufresne AM, Melich G, Vikis E, MacKenzie S. Resection of ruptured hepatic teratoma in an adult. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:414-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shannon NB, Chan NHL, Teo MCC. Recurrence of immature ovarian teratoma as malignant follicular carcinoma with liver and peritoneal metastasis 22 years after completion of initial treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Byun JC, Choi IJ, Han MS, Lee SC, Roh MS, Cha MS. Soft tissue metastasis of an immature teratoma of the ovary. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1689-1693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Malek-Hosseini SA, Baezzat SR, Shamsaie A, Geramizadeh B, Salahi R, Salahi H, Lotfi M. Huge immature teratoma of the liver in an adult: a case report and review of the literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2010;3:332-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Paradies G, Zullino F, Orofino A, Leggio S. Rare extragonadal teratomas in children: complete tumor excision as a reliable and essential procedure for significant survival. Clinical experience and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2014;85:56-68. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Pietzak EJ, Assel M, Becerra MF, Tennenbaum D, Feldman DR, Bajorin DF, Motzer RJ, Bosl GJ, Carver BS, Sjoberg DD, Sheinfeld J. Histologic and Oncologic Outcomes Following Liver Mass Resection With Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection in Patients With Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumor. Urology. 2018;118:114-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oh D, Yi NJ, Song S, Kim OK, Hong SK, Yoon KC, Ahn SW, Kim HS, Kim H, Kim HY, Kang HJ, Lee M, Lee KB, Lee KW, Suh KS. Split liver transplantation for retroperitoneal immature teratoma masquerading as hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Transplant. 2017;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cho A, Kim SW, Choi J, Kang W, Lee JD, Yun M. The additional value of attenuation correction CT acquired during 18F-FDG PET/CT in differentiating mature from immature teratomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:e193-e196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kataria SP, Varshney AN, Nagar M, Mandal AK, Jha V. Growing Teratoma Syndrome. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2017;8:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | O'Reilly D, Alken S, Fiore B, Dooley L, Prior L, Hoti E, Fennelly D. Growing Teratoma Syndrome of the Liver in a 22-Year-Old Female. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9:124-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hiester A, Nettersheim D, Nini A, Lusch A, Albers P. Management, Treatment, and Molecular Background of the Growing Teratoma Syndrome. Urol Clin North Am. 2019;46:419-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kapoor V, Ferris JV, Rajendiran S. Growing teratoma syndrome of the liver: treatment with living related donor liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:839-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eghtesad B, Marsh WJ, Cacciarelli T, Geller D, Reyes J, Jain A, Fontes P, Devera M, Fung J. Liver transplantation for growing teratoma syndrome: report of a case. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1222-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Strohschneider T, Timm D, Worbes C. [Ectopic thyroid gland tissue in the liver]. Chirurg. 1993;64:751-753. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Watanabe I, Kasai M, Suzuki S. True teratoma of the liver--report of a case and review of the literature--. Acta Hepatogastroenterol (Stuttg). 1978;25:40-44. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Winter TC, Freeny P. Hepatic teratoma in an adult. Case report with a review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:308-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Martin LC, Papadatos D, Michaud C, Thomas J. Best cases from the AFIP: liver teratoma. Radiographics. 2004;24:1467-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xu AM, Gong SJ, Song WH, Li XW, Pan CH, Zhu JJ, Wu MC. Primary mixed germ cell tumor of the liver with sarcomatous components. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:652-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Han SY. Dermoid cyst of the liver. Report of a case. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970;109:842-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Russia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Badessi G S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ