Published online May 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i5.253

Peer-review started: December 18, 2019

First decision: January 19, 2020

Revised: January 24, 2020

Accepted: April 18, 2020

Article in press: April 18, 2020

Published online: May 27, 2020

Processing time: 160 Days and 14.5 Hours

Cryptococcosis is a fungal infection caused by the yeast-like encapsulated basidiomycetous fungus of the Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) species complex. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and bird droppings, and infection by them is an important global health concern, particularly in immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients and those infected by the human immunodeficiency virus. The fungus usually enters the body through the respiratory tract, but extremely rare cases of infection acquired by transplantation of solid organs have been reported.

We report a case of disseminated cryptococcosis in a liver transplant recipient, diagnosed 2 wk after the procedure. The patient initially presented with fever, hyponatremia and elevated transaminase levels, manifesting intense headache after a few days. Blood cultures were positive for C. neoformans. Liver biopsy showed numerous fungal elements surrounded by gelatinous matrix and sparse granulomatous formations. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed multiple small lesions with low signal in T2, peripheric enhancement and edematous halo, diffuse through the parenchyma but more concentrated in the subcortical regions. Treatment with amphotericin B for 3 wk, followed by maintenance therapy with fluconazole, led to complete resolution of the symptoms. The recipients of both kidneys from the same donor also developed disseminated cryptococcosis, confirming the transplant as the source of infection. The organ donor lived in a rural area, surrounded by tropical rainforest, and had negative blood cultures prior to organ procurement.

This case highlights the risk of transmission of fungal diseases, specifically of C. neoformans, through liver graft during liver transplantation.

Core tip: Transmission of cryptococcosis through a liver graft during transplantation is an exceedingly rare occurrence, with less than 10 cases reported in the literature. Many of these patients either died or were followed for only a short period of time prior to the report, so there is little information about long term follow-up of patients with this condition. We report the case of a patient who acquired disseminated cryptococcosis from a liver graft during transplantation and was successfully treated, along with the results of follow-up biopsies and imaging exams up to 3.5 years after the transplant.

- Citation: Ferreira GSA, Watanabe ALC, Trevizoli NC, Jorge FMF, Couto CF, de Campos PB, Caja GON. Transmission of cryptococcosis by liver transplantation: A case report and review of literature. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(5): 253-261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i5/253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i5.253

Cryptococcosis is a fungal infection caused by the yeast-like encapsulated basidiomycetous fungus of the Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) species complex. This fungus is ubiquitous in soil and tree bark and is found in particularly great concentrations in the nitrogen-rich environment that is present in the droppings of birds, bats and other vertebrates. It can also be found in up to 50% of domestic dust samples[1]. There are two pathogenic species: C. neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii (C. gattii). Approximately 95% of reported cryptococcal infections are caused by C. neoformans serotype A, with the remaining 5% caused by other serotypes or by C. gattii[2].

The fungus presents as an oval or globular yeast at microscopy, with a diameter of 3 mm to 8 mm, and is characteristically surrounded by a mucopolysaccharidal capsule[1]. The capsule has a high content of melanin, produced as a result of the action of the phenoloxidase enzyme. Brain tissue is rich in substrates for phenoloxidase action, which may at least in part explain the tropism of Cryptococcus for the central nervous system (CNS)[1]. Cryptococcus has several characteristics that underlie increased virulence, including thermotolerance and variations in composition of its cell wall and capsule. There are reports of infection by Cryptococcus in dogs, cats, horses, sheep, snakes, and porpoises. Birds appear to be relatively resistant to this infection, possibly due to their high body temperature[3].

C. neoformans was first described in 1894, isolated from fermenting peach juice[4,5]. That same year, it was first described as a human pathogen, having infected a young woman with osteomyelitis[5]. Cryptococcosis was first reported in Brazil in 1941, in a patient with pulmonary disease[6]. Infection usually occurs by inhalation of basidiospores and dry yeasts but it can also occur through the gastrointestinal tract[2,7]. In the pulmonary alveoli, the fungus comes in contact with alveolar macrophages, which play a central role in the initial immune response. The macrophages internalize the fungal structures through phagocytosis, and Cryptococcus is able to survive and replicate inside the vacuole despite acidification. After replication, it can exit the host cell by a lytic process that destroys the host cell, or by a non-lytic process that leaves both cells intact[5].

The most common site of symptomatic cryptococcosis is the CNS, which is affected in about 80% of patients with the disease, and usually presents as a subacute or chronic meningitis with or without hydrocephalus, or less commonly as cerebral cryptococcomas, which may be confused for brain neoplasms in imaging evaluation[1]. The most common symptoms are headache, fever and confusion, but ataxia, amaurosis and cranial nerve palsies may also occur[8,9]. Signs of meningeal irritation are present in about 50% of patients[10]. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion may occur as a complication of cryptococcal meningitis and can cause severe hyponatremia[11]. There are reports from endemic areas in Brazil where C. gattii is the main causative agent of meningeal cryptococcosis, but C. neoformans remains the most common agent throughout the world[12].

Pulmonary disease is the second most common manifestation of cryptococcosis, presenting as pulmonary consolidations, nodular or cavitary infiltrates, miliary pattern, or rarely as pleural effusion, and may be unilateral or bilateral[1]. Symptoms of pulmonary disease include coughing, fever, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis, but it can be asymptomatic in up to 30% of patients[1,13].

Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present as nodular lesions with a central umbilication, mimicking molluscum contagiosum, or as areas of swelling and erythema, similar in aspect to bacterial cellulitis. The most common sites for cryptococcal skin lesions are the lower extremities (65% of cases) and the trunk (26%)[14]. Subcutaneous abscesses are a rare manifestation of cryptococcosis, described mainly in solid organ transplant recipients[15].

Cryptococcal peritonitis is clinically similar to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and usually occurs in cirrhotic patients[16]. Hepatic cryptococcal infection is rare but may occur in disseminated disease, usually manifesting as cholestatic jaundice that may rapidly progress to liver failure and death[17]. Disease affecting more than one organ is considered as disseminated cryptococcosis. Vertical transmission of cryptococcosis during pregnancy is extremely rare[1].

The diagnosis of cryptococcosis can be made by direct microscopy of sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, urine, or organ biopsy. The use of India ink is helpful in the identification of fungal elements, having a 50%-80% sensitivity. Fungal culture can also be obtained from the same kind of samples, and colony growth is usually observed in 48 h to 72 h using mediums such as Sabouraud agar or blood agar, and having a sensitivity of 70%-90%. A latex agglutination test can be used to detect Cryptococcus antigens in serum and CSF, having a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 98%. Titers above 1:8 strongly suggest active cryptococcosis, and titration can be used as a parameter to assess the response to antifungal treatment. Serum antigen does not cross the blood-brain barrier, and therefore does not interfere with titers detected in the CSF. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can also be used for the detection of both antigens and antibodies to Cryptococcus, with even greater sensitivity. Analysis of the CSF usually shows pleocytosis with lymphocytosis, an increase in protein content, and a decrease in glucose[1,2]. Imaging of the brain in patients with cryptococcosis affecting the CNS can show leptomeningeal enhancement, encephalomalacia, infarcts, cerebellitis, hydrocephalus, transverse myelitis, or the presence of cryptococcomas. In these patients, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is more sensitive than computerized tomography (CT), which can be normal in 50% of patients[10,18,19]. Analysis of the ascitic fluid in patients with cryptococcal peritonitis is highly variable but seldom shows significant pleocytosis and usually shows an increase in lymphocytes[16].

Recommendations for the treatment of cryptococcosis vary according to the site of infection and the immunological status of the host. Amphotericin B (0.7 mg/kg daily) in combination with flucytosine or fluconazole for 2 wk to 10 wk is the recommended induction treatment for cryptococcal meningitis, followed by a maintenance treatment of 12-24 mo with daily fluconazole or itraconazole. Refractory cases should be treated with higher doses (3-6 mg/kg daily) of amphotericin B for another 6-10 wk. High doses of fluconazole (800-2000 mg daily) can be used if amphotericin B is not tolerated or unavailable. Intrathecal infusion of amphotericin B has multiple side effects and should only be used in refractory cases[20]. Voriconazole and posaconazole can also be treatment alternatives for these patients. Echinocandins appear to have no efficacy against Cryptococcus. Intermittent lumbar punctures can be of great importance in the first weeks of the treatment to alleviate intracranial hypertension, which is a significant source of mortality in cryptococcal meningitis.

There is no consensus in the current literature regarding persistent inflammatory lesions in the brain during treatment. The complete regression of these lesions can take a long time, and analysis of the CSF is of limited value to assess the presence of Cryptococcus in the brain parenchyma. If the lesions persist after the full treatment course has been completed, and the patient remains asymptomatic and with negative cultures, the suspension of the antifungal drugs appears to be safe, as long as adequate clinical and imaging follow-up can be obtained[21].

Treatment for pulmonary cryptococcosis consists of fluconazole (200 mg to 400 mg daily) for 6-12 mo.

In solid organ transplant recipients afflicted with cryptococcosis, an important adjuvant for antifungal treatment will involve reduction of the immunosuppressive drug regimen to the lowest possible levels, in order to increase host cellular immunity against the fungus[3].

Incidence of cryptococcosis in solid organ recipients has been estimated at 0.3% up to 5%, being the third most commonly occurring invasive fungal infection in this population[8,22]. Mortality ranges from 15%-20% but may be as high as 40% when infection of the CNS is present[23,24]. Among solid organ transplant recipients, lung and liver recipients appear to the be the most vulnerable to cryptococcosis, but mortality is higher in heart transplant patients[25,26]. The onset of the disease after the transplant usually ranges from 8-21 mo but may occur many years after the procedure[6,8,27,28]. Patients who develop cryptococcosis more than 24 mo after transplantation are more likely to have CNS disease than those with early-onset disease[29].

Since many antifungals, such as fluconazole, are inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 enzymes, a reduction of about 40%-50% in the dose of tacrolimus may be warranted in order to maintain therapeutic drug levels[4].

Cirrhosis is an independent risk factor for the development of cryptococcosis, particularly for cryptococcal peritonitis, and the possibility that early-onset disease after the transplant actually represents an increase in the symptoms of preexisting disease must be considered[30-32]. If adequately treated before the transplant, cryptococcosis is not a contraindication for liver transplantation[33]. There are some reports on the transmission of Cryptococcus by organ transplantation, and early (less than 4 wk after the procedure) post-transplant cryptococcosis warrants consideration of donor transmission[6,34,35]. There are well recorded cases of transmission by corneal[36,37], lung[38], kidney[39-41] and liver transplants[42-44].

At 14 d after the surgery, a 57-year-old male returned to the emergency room complaining of fever and malaise.

The patient reported fever (39 °C), chills and loss of appetite that had started 5 d after hospital discharge.

A 57-year-old male diagnosed with cryptogenic cirrhosis – with hepatic encephalopathy being the main manifestation of the disease – underwent liver transplant in a Brazilian tertiary care hospital. At the time of transplantation, the patient’s model for end-stage liver disease score was 14 and Child-Pugh classification was class B (8 points). Prior to the procedure, the patient had been admitted to the hospital several times for hepatic encephalopathy and suffered two major episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Investigation for viral hepatitis and autoimmune disease had negative results, and there was no previous history of significant alcohol consumption. The patient worked as a farmer in a rural area located in the North of Brazil, had no comorbidities, and suffered from frequent and severe symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy in spite of optimal clinical treatment. He had a previous CT scan of the brain, with no abnormal findings, and both an ultrasound and a CT scan of the abdomen, which were unremarkable except for portal hypertension and liver cirrhosis.

The patient was submitted to orthotopic liver transplantation with a graft obtained from a cadaveric donor (53-year-old male), in whom brain death had been caused by a hemorrhagic stroke that occurred 3 d before organ procurement. The donor worked as a lumberjack in the rural area of the North region of Brazil and was reported as being previously healthy, having normal biochemical tests, and no evidence of ongoing infection at the moment of organ procurement. He had positive results for serological tests for anti-HBs and anti-HBc but negative result for the serological test for HBsAg; these findings suggested a resolved hepatitis B infection. The transplantation procedure was uneventful, with a total ischemia time of 9 h and 9 min, no intraoperative complications, and no need for blood product transfusions. The patient was discharged from the intensive care unit 3 d after the procedure and from the hospital 8 d after the transplant.

The patient had no significant comorbidities, other than the recent transplant. He had no pulmonary, neurological or genitourinary symptoms. His immunosuppressive drug regimen consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisone, with a blood level of tacrolimus of 11.4 ng/mL.

Physical examination was unremarkable, with absence of skin lesions, vital signs within the normal range of values, and no signs of infection in the surgical wound. Neurological examination was completely normal. The patient was admitted to the hospital for investigation. As he remained hemodynamically stable, admission to the intensive care unit was not deemed to be necessary.

Blood and urine cultures were obtained, producing growth of C. neoformans after 48 h in two separate blood cultures. Biochemical tests showed normal leukocyte and platelet counts, and levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine within the normal range. Remarkable findings were anemia (hemoglobin concentration of 8.1 g/dL; normal range: 13.5-17.5 g/dL), hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin of 5.3 mg/dL; normal range: 0.1-1.2 mg/dL), hyponatremia (sodium concentration of 119 mmol/L; normal range: 136-145 mmol/L), increased gamma-glutamyl transferase (referred to as GGT) (1470 UI/L; normal range: 9-48 UI/L), alanine aminotransferase (referred to as ALT) (45 UI/L; normal range: 7-56 UI/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (referred to as AST) (132 UI/L; normal range: 10-40 UI/L). A lumbar puncture was obtained, with the analysis of CSF showing values of glucose, protein and cytology all within normal range. CSF culture was negative for fungal growth.

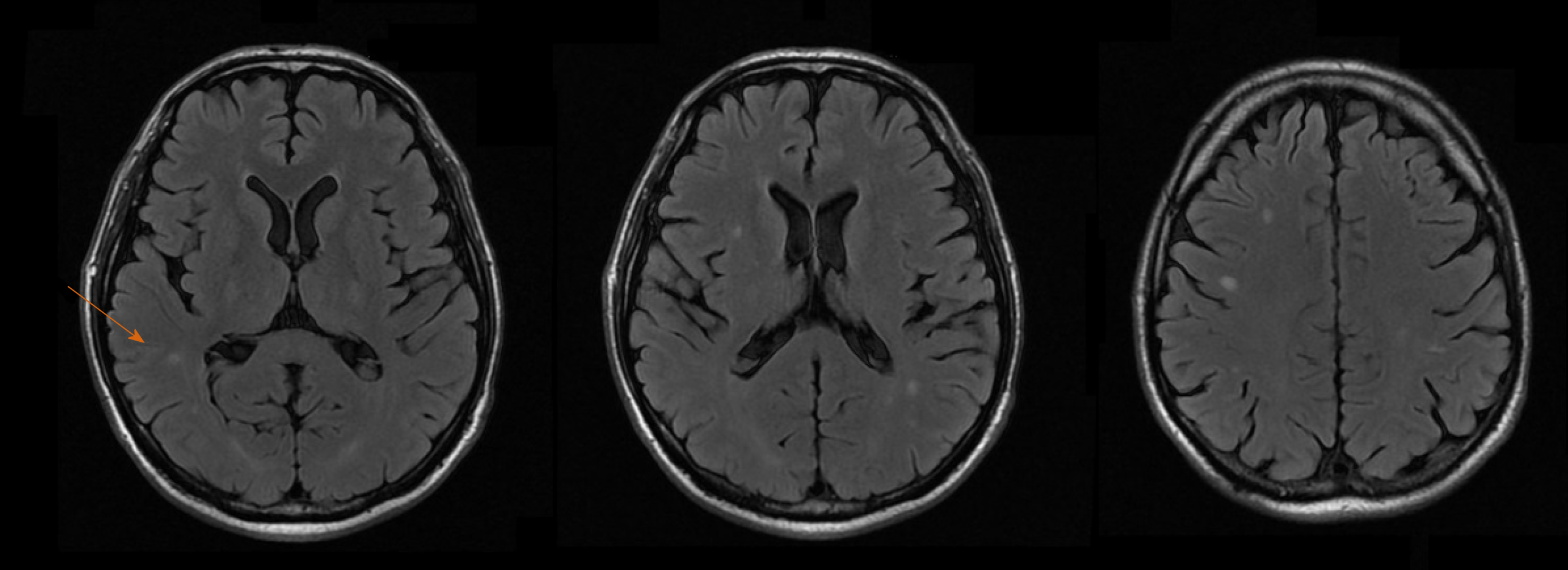

An ultrasound of the liver with doppler evaluation of the hepatic vessels was performed and gave normal results. An X-ray of the chest was also normal. An MRI of the brain was obtained, showing multiple small lesions with low signal in T2, peripheric enhancement and edematous halo, diffuse through the parenchyma but more concentrated in the subcortical regions (Figure 1).

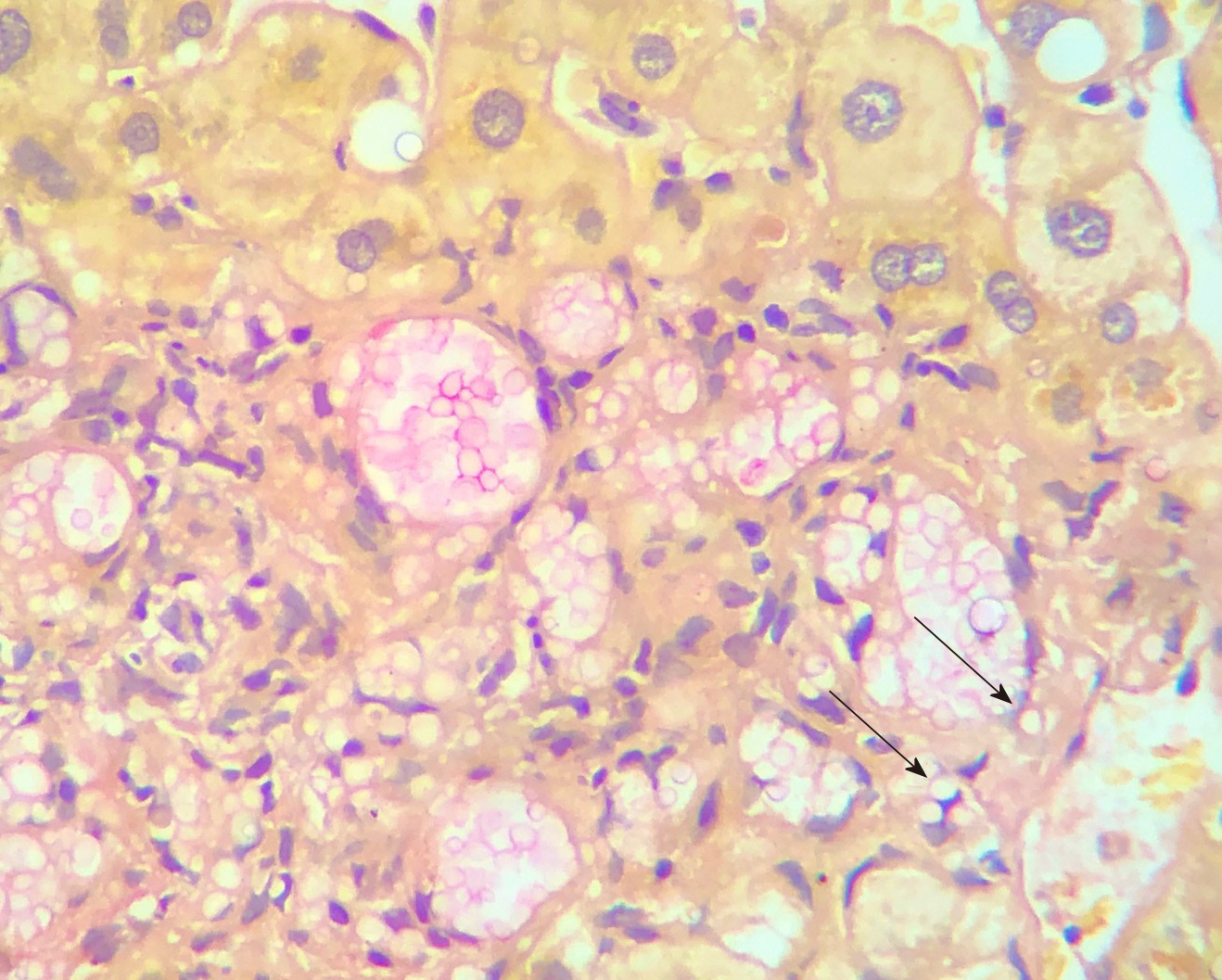

A liver biopsy was obtained and investigated by histological analysis carried out by an expert in liver pathologies (Dr. ESM).

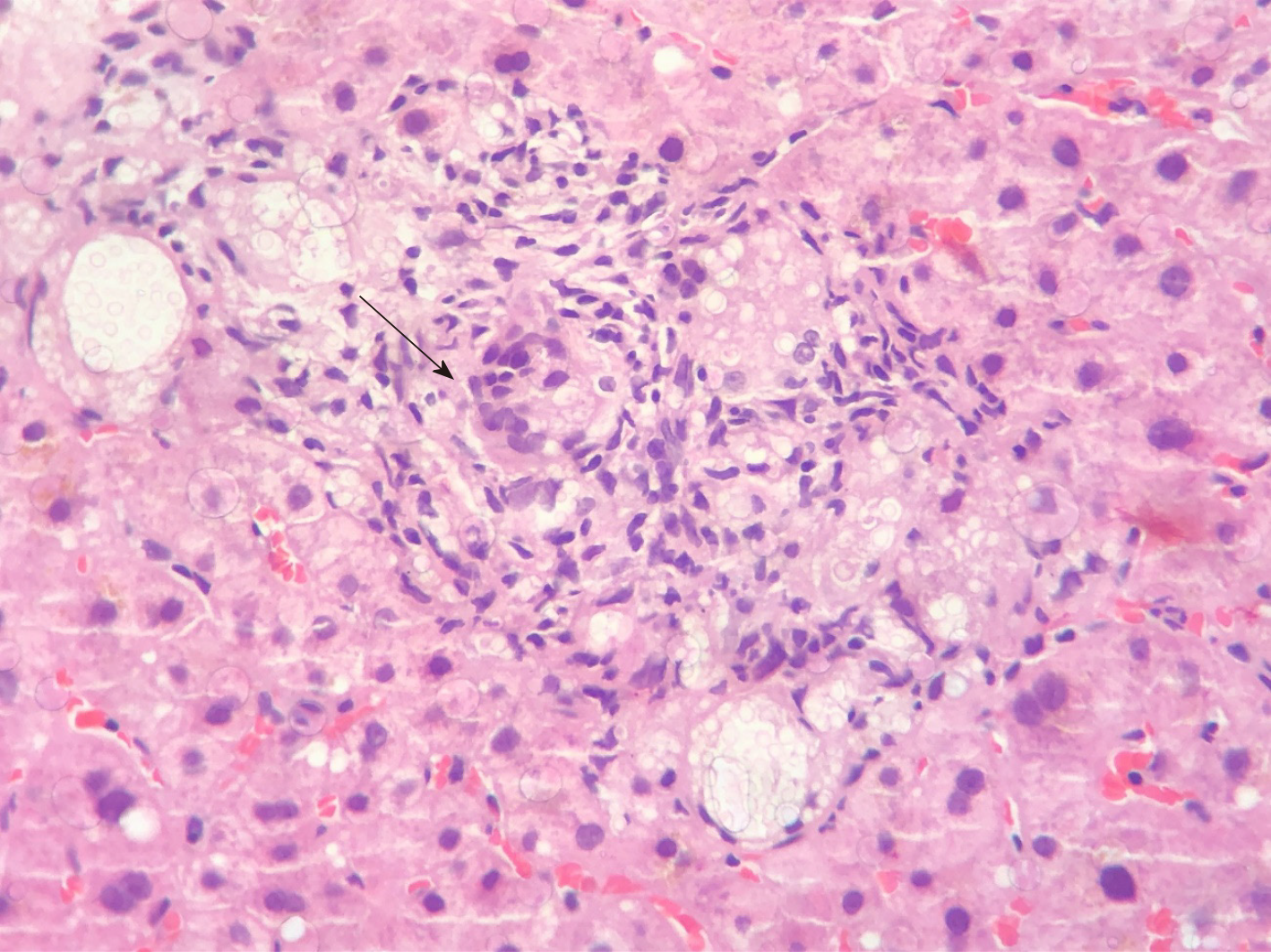

Histology of the liver biopsy showed a large number of fungal elements immersed in gelatinous matrix, in both liver parenchyma and portal spaces, with some of them surrounded by a loose histiocytic response (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with disseminated cryptococcosis, affecting both the CNS and the liver graft.

Treatment was initiated with liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg) in combination with fluconazole for 3 wk, followed by maintenance treatment with oral fluconazole (450 mg daily). Mycophenolate was discontinued and tacrolimus dosage was adjusted according to serum levels, which eventually stabilized around 8 ng/mL, with the patient taking 1 mg of tacrolimus on alternate days. The patient remained afebrile and asymptomatic after the amphotericin B treatment, showing marked decrease in total bilirubin levels (1 mg/dL) and progressive decrease in GGT levels (1162 UI/L).

Early disseminated cryptococcosis was also reported in the recipients of both kidneys obtained from the same donor of our liver transplant recipient; those transplants had occurred in hospitals located in different parts of the country. We concluded that the donor, while reportedly asymptomatic, had disseminated cryptococcosis that was transmitted by the grafts to the recipients. Our patient remained asymptomatic and with laboratory tests showing normal range of values for the 3.5 years of outpatient follow-up. The fluconazole dosage was progressively reduced to the current dosage of 150 mg daily. Control MRIs of the brain were obtained at 6, 12, 18 and 36 mo, all showing persistence of the brain lesions but with gradual reduction of the contrast enhancing halo around them. Liver biopsies were obtained at 4 and 16 mo, initially showing numerous granulomas containing oval fungal structures (Figure 3) and finally the absence of fungal structures, respectively.

Diagnosis and treatment of disseminated cryptococcosis in recipients of solid organ transplantation remains a clinical challenge, given the unspecific nature of the initial symptoms, the need for reduction in immunosuppression – which may cause rejection, and the adverse reactions associated with antifungal treatment. In the case we report, diagnosis of disseminated disease was obtained by growth of Cryptococcus in blood cultures. The CSF cultures and direct microbiology tests were negative despite the presence of multiple brain lesions, highlighting the poor correlation between the presence of the fungus in the CSF and in the brain parenchyma. Serological tests were unavailable at our institution at that time. The patient also presented with severe hyponatremia, which may have been associated with CNS cryptococcosis infection, and increases the morbidity of the disease. The patient also had a marked increase in bilirubin and liver enzymes caused by fungal infiltration of the liver, which was diagnosed by liver biopsy and quickly improved after antifungal treatment was initiated. The fact that all recipients (both kidneys and liver) who received organs from the same donor reported here developed early disseminated cryptococcosis, makes transmission by the transplant the most likely means of contagion in this case. This impression is reinforced by the presence of Cryptococcus in the biopsies of all three transplanted organs. In the cases of suspected or confirmed transmission of cryptococcosis through a liver transplant previously reported in the literature, the most common outcome was the death of the organ recipient[17,31,44]. Chang et al[42] reported on a patient who developed hepatic and pulmonary cryptococcosis one week after a liver transplant and was successfully treated with amphotericin B. We have found no previous reports in the literature of long-term follow-up of a liver transplant recipient with disseminated cryptococcosis, which allowed us to document the complete clearance of fungal structures in the liver 16 mo after treatment was started, and the long-term persistence of brain lesions in a asymptomatic patient with no other signs of infection.

Cryptococcosis is a relatively common fungal infection in patients that undergo liver transplantation, causing significant morbidity and mortality in this population. The most severe form of disease is disseminated cryptococcosis, with infection reaching multiple organs through the bloodstream. Treatment involves both a reduction of the immunosuppressive drug regimen and prolonged antifungal treatment. While most cases of cryptococcosis in solid organ recipients is caused by reactivation of their latent disease due to immunosuppression, in rare cases, the infection may be acquired through the liver graft, which may be suspected in cases of early infection after the transplant. Maintenance of prolonged antifungal treatment, even in asymptomatic patients, is important, since complete elimination of viable fungal elements in liver tissue may take more than a year of treatment to be achieved.

The authors would like to acknowledge the important contribution by Dr. Evandro Sobroza de Mello and the CICAP laboratory, in the diagnostic investigation and follow-up of the case reported, as well as in the elaboration of this manuscript.

| 1. | Moretti ML, Resende MR, Lazéra MS, Colombo AL, Shikanai-Yasuda MA. [Guidelines in cryptococcosis--2008]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:524-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:179-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | da Silva EC, Guerra JM, Torres LN, Lacerda AM, Gomes RG, Rodrigues DM, Réssio RA, Melville PA, Martin CC, Benesi FJ, de Sá LR, Cogliati B. Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII infection associated with lung disease in a goat. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wald-Dickler N, She R, Blodget E. Cryptococcal disease in the solid organ transplant setting: review of clinical aspects with a discussion of asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Srikanta D, Santiago-Tirado FH, Doering TL. Cryptococcus neoformans: historical curiosity to modern pathogen. Yeast. 2014;31:47-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pappalardo MC, Melhem MS. Cryptococcosis: a review of the Brazilian experience for the disease. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2003;45:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vilchez RA, Fung J, Kusne S. Cryptococcosis in organ transplant recipients: an overview. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang YL, Chen M, Gu JL, Zhu FY, Xu XG, Zhang C, Chen JH, Pan WH, Liao WQ. Cryptococcosis in kidney transplant recipients in a Chinese university hospital and a review of published cases. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:154-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wirth F, Azevedo MI, Goldani LZ. Molecular types of Cryptococcus species isolated from patients with cryptococcal meningitis in a Brazilian tertiary care hospital. Braz J Infect Dis. 2018;22:495-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koshy JM, Mohan S, Deodhar D, John M, Oberoi A, Pannu A. Clinical Diversity of CNS Cryptococcosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mansoor S, Juhardeen H, Alnajjar A, Abaalkhail F, Al-Kattan W, Alsebayel M, Al Hamoudi W, Elsiesy H. Hyponatremia as the Initial Presentation of Cryptococcal Meningitis After Liver Transplantation. Hepat Mon. 2015;15:e29902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Santos WR, Meyer W, Wanke B, Costa SP, Trilles L, Nascimento JL, Medeiros R, Morales BP, Bezerra Cde C, Macêdo RC, Ferreira SO, Barbosa GG, Perez MA, Nishikawa MM, Lazéra Mdos S. Primary endemic Cryptococcosis gattii by molecular type VGII in the state of Pará, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singh N, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Gupta KL, John GT, del Busto R, Klintmalm GB, Somani J, Lyon GM, Pursell K, Stosor V, Muñoz P, Limaye AP, Kalil AC, Pruett TL, Garcia-Diaz J, Humar A, Houston S, House AA, Wray D, Orloff S, Dowdy LA, Fisher RA, Heitman J, Wagener MM, Husain S. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients: clinical relevance of serum cryptococcal antigen. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e12-e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Forrest GN, Lyon GM, Somani J, Gupta KL, Del Busto R, Pruett TL, Sifri CD, Limaye AP, John GT, Klintmalm GB, Pursell K, Stosor V, Morris MI, Dowdy LA, Muñoz P, Kalil AC, Garcia-Diaz J, Orloff SL, House AA, Houston SH, Wray D, Huprikar S, Johnson LB, Humar A, Razonable RR, Fisher RA, Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N; Cryptococcal Collaborative Transplant Study Group. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Singh N, Gayowski T, Marino IR. Successful treatment of disseminated cryptococcosis in a liver transplant recipient with fluconazole and flucytosine, an all oral regimen. Transpl Int. 1998;11:63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park WB, Choe YJ, Lee KD, Lee CS, Kim HB, Kim NJ, Lee HS, Oh MD, Choe KW. Spontaneous cryptococcal peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Am J Med. 2006;119:169-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lu S, Furth EE, Blumberg EA, Bing Z. Hepatic involvement in a liver transplant recipient with disseminated cryptococcosis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ecevit IZ, Clancy CJ, Schmalfuss IM, Nguyen MH. The poor prognosis of central nervous system cryptococcosis among nonimmunosuppressed patients: a call for better disease recognition and evaluation of adjuncts to antifungal therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1443-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baddley JW, Forrest GN; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Cryptococcosis in solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Day JN, Chau TTH, Wolbers M, Mai PP, Dung NT, Mai NH, Phu NH, Nghia HD, Phong ND, Thai CQ, Thai LH, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, Duong VA, Hoang TN, Diep PT, Campbell JI, Sieu TPM, Baker SG, Chau NVV, Hien TT, Lalloo DG, Farrar JJ. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1291-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alexander BD. Cryptococcosis after solid organ transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Gupta KL, John GT, Del Busto R, Klintmalm GB, Somani J, Lyon GM, Pursell K, Stosor V, Munoz P, Limaye AP, Kalil AC, Pruett TL, Garcia-Diaz J, Humar A, Houston S, House AA, Wray D, Orloff S, Dowdy LA, Fisher RA, Heitman J, Albert ND, Wagener MM, Singh N. Calcineurin inhibitor agents interact synergistically with antifungal agents in vitro against Cryptococcus neoformans isolates: correlation with outcome in solid organ transplant recipients with cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:735-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ponzio V, Chen Y, Rodrigues AM, Tenor JL, Toffaletti DL, Medina-Pestana JO, Colombo AL, Perfect JR. Genotypic diversity and clinical outcome of cryptococcosis in renal transplant recipients in Brazil. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8:119-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in organ transplant recipients: variables influencing clinical characteristics and outcome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | George IA, Santos CAQ, Olsen MA, Powderly WG. Epidemiology of Cryptococcosis and Cryptococcal Meningitis in a Large Retrospective Cohort of Patients After Solid Organ Transplantation. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Singh N, Dromer F, Perfect JR, Lortholary O. Cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients: current state of the science. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1321-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Marques S, Carmo R, Ferreira I, Bustorff M, Sampaio S, Pestana M. Cryptococcosis in Renal Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2289-2293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Osawa R, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Forrest GN, Lyon GM, Somani J, Gupta KL, Del Busto R, Pruett TL, Sifri CD, Limaye AP, John GT, Klintmalm GB, Pursell K, Stosor V, Morris MI, Dowdy LA, Muñoz P, Kalil AC, Garcia-Diaz J, Orloff S, House AA, Houston S, Wray D, Huprikar S, Johnson LB, Humar A, Razonable RR, Fisher RA, Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N. Identifying predictors of central nervous system disease in solid organ transplant recipients with cryptococcosis. Transplantation. 2010;89:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Singh N. How I treat cryptococcosis in organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2012;93:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lin YY, Shiau S, Fang CT. Risk factors for invasive Cryptococcus neoformans diseases: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Forrest GN, Lyon GM, Somani J, Gupta KL, del Busto R, Pruett TL, Sifri CD, Limaye AP, John GT, Klintmalm GB, Pursell K, Stosor V, Morris MI, Dowdy LA, Munoz P, Kalil AC, Garcia-Diaz J, Orloff SL, House AA, Houston SH, Wray D, Huprikar S, Johnson LB, Humar A, Razonable RR, Fisher RA, Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N; Cryptococcal Collaborative Transplant Study Group. Unrecognized pretransplant and donor‐derived cryptococcal disease in organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1062-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Singh N, Sun HY. Iron overload and unique susceptibility of liver transplant recipients to disseminated disease due to opportunistic pathogens. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1249-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sifri CD, Sun HY, Cacciarelli TV, Wispelwey B, Pruett TL, Singh N. Pretransplant cryptococcosis and outcome after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:499-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Powderly WG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:710-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 754] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Beyt BE, Waltman SR. Cryptococcal endophthalmitis after corneal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:825-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | de Castro LE, Sarraf OA, Lally JM, Sandoval HP, Solomon KD, Vroman DT. Cryptococcus albidus keratitis after corneal transplantation. Cornea. 2005;24:882-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kanj SS, Welty-Wolf K, Madden J, Tapson V, Baz MA, Davis RD, Perfect JR. Fungal infections in lung and heart-lung transplant recipients. Report of 9 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:142-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | MacEwen CR, Ryan A, Winearls CG. Donor transmission of Cryptococcus neoformans presenting late after renal transplantation. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Agrawal C, Sood V, Kumar A, Raghavan V. Cryptococcal Infection in Transplant Kidney Manifesting as Chronic Allograft Dysfunction. Indian J Nephrol. 2017;27:392-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ooi BS, Chen BT, Lim CH, Khoo OT, Chan DT. Survival of a patient transplanted with a kidney infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Transplantation. 1971;11:428-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chang CM, Tsai CC, Tseng CE, Tseng CW, Tseng KC, Lin CW, Wei CK, Yin WY. Donor-derived Cryptococcus infection in liver transplant: case report and literature review. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12:74-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ison MG, Hager J, Blumberg E, Burdick J, Carney K, Cutler J, Dimaio JM, Hasz R, Kuehnert MJ, Ortiz-Rios E, Teperman L, Nalesnik M. Donor-derived disease transmission events in the United States: data reviewed by the OPTN/UNOS Disease Transmission Advisory Committee. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1929-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Baddley JW, Schain DC, Gupte AA, Lodhi SA, Kayler LK, Frade JP, Lockhart SR, Chiller T, Bynon JS, Bower WA. Transmission of Cryptococcus neoformans by Organ Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e94-e98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cimen SG, El-Raziky M, Gencdal G, Moralioglu S, Tsuchiya A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu XYJ