Published online Mar 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i3.294

Peer-review started: December 29, 2018

First decision: January 27, 2019

Revised: January 27, 2019

Accepted: March 12, 2019

Article in press: March 12, 2019

Published online: March 27, 2019

Processing time: 89 Days and 19.7 Hours

Although hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most vascular solid tumors, antiangiogenic therapy has not induced the expected results.

To uncover immunohistochemical (IHC) aspects of angiogenesis in HCC.

A retrospective cohort study was performed and 50 cases of HCC were randomly selected. The angiogenesis particularities were evaluated based on the IHC markers Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A and the endothelial area (EA) was counted using the antibodies CD31 and CD105.

The angiogenic phenotype evaluated with VEGF-A was more expressed in small tumors without vascular invasion (pT1), whereas COX-2 was rather expressed in dedifferentiated tumors developed in non-cirrhotic liver. The CD31-related EA value decreased in parallel with increasing COX-2 intensity but was higher in HCC cases developed in patients with cirrhosis. The CD105-related EA was higher in tumors developed in patients without associated hepatitis.

In patients with HCC developed in cirrhosis, the newly formed vessels are rather immature and their genesis is mediated via VEGF. In patients with non-cirrhotic liver, COX-2 intensity and number of mature neoformed vessels increases in parallel with HCC dedifferentiation.

Core tip: In this paper we showed a possible role of morphological and immunohistochemical features of Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in predicting the individualized antiangiogenic therapy of HCC. Based on the results and literature data, it seems that dedifferentiated HCCs developed in non-cirrhotic liver are predominantly driven via Cyclooxygenase-2 axis, whereas vascular endothelial growth factor-A induces hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with HCCs developed on the cirrhosis background.

- Citation: Fodor D, Jung I, Turdean S, Satala C, Gurzu S. Angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma: An immunohistochemistry study. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(3): 294-304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i3/294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i3.294

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic primary malignant tumor (over 70% of cases) which globally ranks fifth in terms of cancer frequency and second in terms of cancer mortality[1-3]. It is a well-vascularized tumor in which angiogenesis plays an important role in development, invasion and metastasis[4]. HCC cells can synthesize angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A, Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF). At the same time, they might produce antiangiogenic factors such as angiostatin and endostatin. Thus, tumor angiogenesis depends on a local balance between these positive and negative regulators[5].

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is an enzyme encoded by the PTGS2 gene, which belongs to the group of endogenous tumor factors that might stimulate genesis and progression of HCC[6]. There are three isoforms: constitutive COX-1, inducible COX-2, and COX-3[3,7]. If COX-1 is present in nearly all types of tissues, being responsible for the synthesis of prostaglandins in normal conditions, COX-2 is induced by cellular stress or tumor promoters, being responsible for the synthesis of prostaglandins involved in inflammation, cell growth, tumor development and progression[3,6,8]. Although the therapeutic inhibition of COX enzymes and prostaglandins was supposed to be linked to lower risk and better survival of HCC[9], the exact mechanism of inhibition and criteria of identification of those cases that can benefit by anti-COX therapy are still unknown.

VEGF is a glycoprotein with an important role in both physiological and pathological angiogenesis. It is located on the 6p chromosome, contains 8 exons[10] and encodes five variants: VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D and PIGF (Placental Growth Factor)[3]. VEGF is the key mediator of formation of new vessels from pre-existing vessels[3].

Microvessel density (MVD) and endothelial area (EA) values are parameters used as prognostic factors in many tumors and can be assessed using immunohistochemical (IHC) markers such CD31 and CD105[11,12]. To determine the MVD, the number of vessels are counted, whereas EA can be semiautomatically quantified and take into account the area of endothelial cells versus total tissue area[13].

CD31 or PECAM-1 (Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1) is a receptor expressed by cells of the hematopoietic system, such as platelets, monocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes, but also by endothelial cells[14]. In the liver, CD31 is diffusely expressed in sinusoids, as opposed to CD34 which is expressed only in hepatic periportal areas[15]. CD31 marks neoformed and preexistent vessels[16].

CD105 or endoglin is a co-receptor for TGF (transforming growth factor)-beta1 and -beta3[16]. It is a marker of proliferating activated endothelial cells[13,16-18].

As the antiangiogenic therapy did not show encouraging results in patients with HCC[19], the aim of this paper was to perform an IHC study and try to identify those cases that might benefit by anti-VEGF-A or anti-COX-2 drugs therapy. The angiogenic phenotype of tumor cells was evaluated with VEGF-A and COX-2, and the value of EA was semiautomatically quantified with CD31 and CD105.

From 2004-2014, in a period of 11 years, all of the 113 cases of HCC were evaluated and 50 cases were randomly selected for angiogenesis quantification. The agreement of the Ethical Commitee of University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tirgu-Mures, Romania, was obtained for retrospective assessment of the cases.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the cases (Table 1) were correlated with the angiogenic parameters. We reassessed the microscopic slides in order to establish the tumor grade (G) and tumor stage (pT) according to AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition[20]. No preoperative radiochemotherapy was done in any of the included cases.

| Variable | Number of cases (n = 50) | Percentage |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 36 | 72 |

| Females | 14 | 28 |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 64.66 ± 9.6 | |

| Age groups | ||

| 31-50 yr | 2 | 4 |

| 51-60 yr | 12 | 24 |

| 61-70 yr | 21 | 42 |

| 71-80 yr | 15 | 30 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD, cm) | 40.12 ± 40.58 | |

| Tumor aspect | ||

| Single nodule | 36 | 72 |

| Multifocality | 14 | 28 |

| Tumor grade | ||

| G1 | 8 | 16 |

| G2 | 24 | 48 |

| G3 | 17 | 34 |

| G4 | 1 | 2 |

| Tumor stage | ||

| T1 | 23 | 46 |

| T2 | 27 | 54 |

| Cirrhosis | ||

| Without | 32 | 64 |

| With | 18 | 36 |

| Mallory bodies | ||

| Without | 36 | 72 |

| With | 14 | 28 |

| Hepatitis | ||

| Without | 26 | 52 |

| With | 24 | 48 |

| Cholestasis | ||

| Without | 41 | 82 |

| With | 9 | 18 |

| Steatosis | ||

| Without | 33 | 66 |

| With | 17 | 34 |

The IHC stains, with antibodies used for examination of the angiogenic immunophenotype of tumor cells (VEGF-A and COX-2) and assessment of the endothelial area (CD31 and CD105), were performed using 5-μm thick sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. For heat-induced antigen retrieval the sections were subjected to incubation with high-pH buffer (pH 9.0) for 30 min. The developing was performed with DAB solution (diaminobenzidine, Novocastra) and counterstaining was done with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Novocastra). For negative controls, incubation was done with omission of specific antibodies. The characteristics of the antibodies are summarized in Table 2.

| Antibody | Clone | Company, town, country | Dilution | External control |

| COX-2 | 4H12 | Novocastra, NewCastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom | 1:100 | Brain-multipolar neurons; renal tubes |

| VEGF | VG1 | LabVision, Fremont, CA, United States | 1:50 | Renal tubes |

| CD31 | JC70A | DAKO,Glostrup, Denmark | 1:40 | Renal glomerules |

| CD105 | SN6H | LabVision, Fremont, CA, United States | 1:50 | Tonsils |

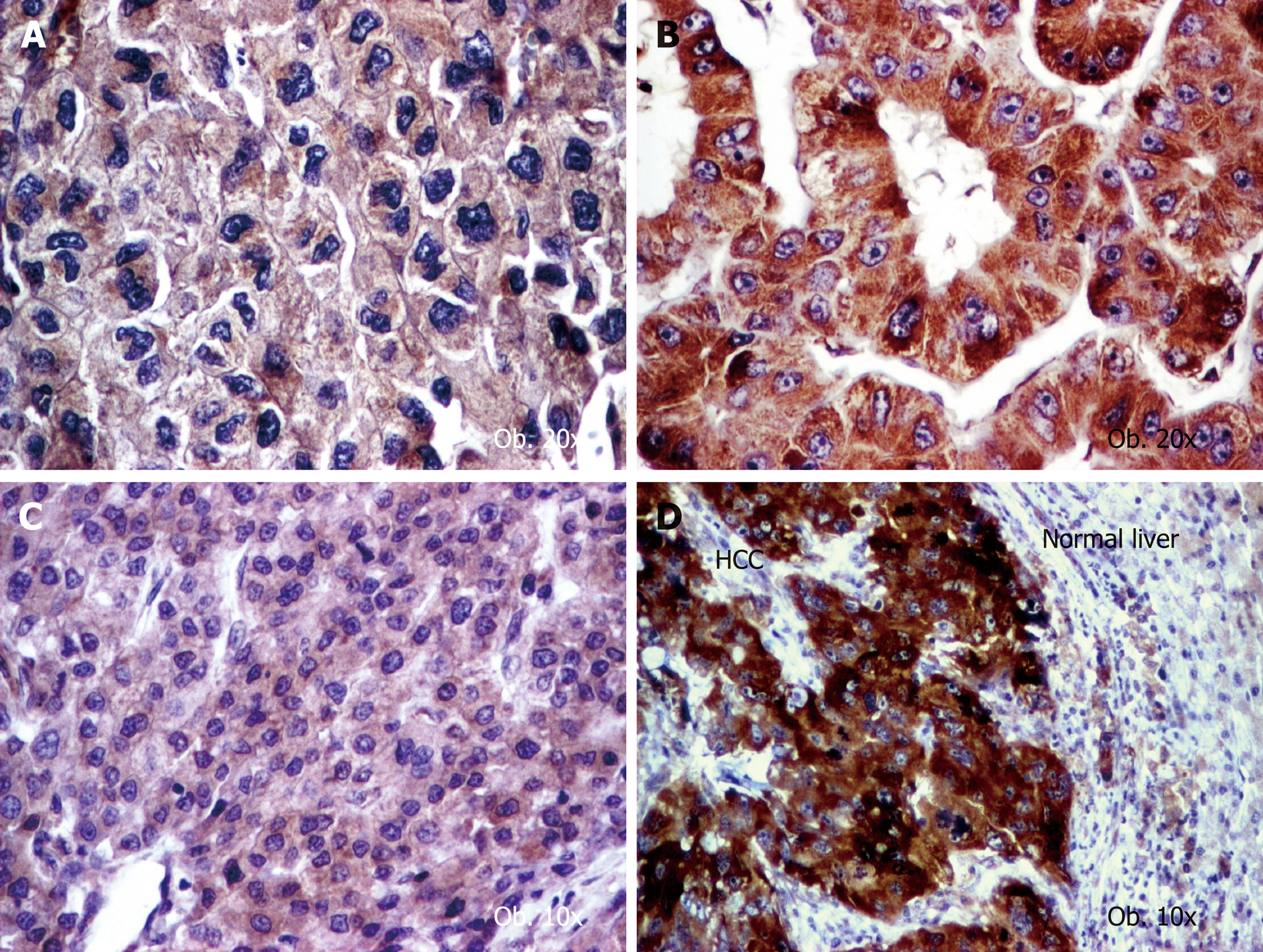

For COX-2 and VEGF-A, the intensity of the IHC reaction was quantified in the cytoplasm of tumor cells, based on the cytoplasmic staining intensity and percentage of positive cells, as follows (Figure 1): negative (no stain or weak positivity < 5% of cells); score 1+ (weak diffuse cytoplasmic staing in 5%-10% of tumor cells); score 2+ (moderate positivity in 10%-70% of cells); score 3+ (strong positivity >70% of tumor tumor cells)[16]. Each slide was independenlty evaluated by three pathologists (SG, IJ and ST).

For the semiautomated assessment of endothelial area (EA), marked with CD31 and CD105, the "hot spot" method was used. Using Nikon E800 microscope, equipped with a digital camera, the areas with the highest vascular density were identified at a magnification of 100x. We discarded the areas with necrosis or rich in inflammatory infiltrate as well as those in which the antibodies have marked nonspecific other elements besides the endothelial cells. We digitally captured the images from "hot spot" areas at 400x high power fields, of intra- and peritumoral regions, performing 5 JPEG format photos per each region[13,16].

The EA was quantified using NIH's ImageJ software. We manually selected the vessels, with or without lumen, that were marked positive, then the software automatically determined the EA, respectively the positive endothelial cells, with or without lumen, and reported it to the total tissue area[13,16]. For statistical purposes, the median value of EA, using the 5 hot-spot pictures, was used.

The statistical assessment was done using the GraphPadInStat 3 statistical software (free access). We calculated the mean ± SD. A P-value < 0.05 with 95% confidence interval was considered statistically significant. We also turned to correlations, Fisher’s Exact Test, using frequency tables for obtaining numerical data and percentage, as well as the ANOVA test and multivariate regressions.

In a period of 11 years, 113 patients were diagnosed with HCC: 81 males and 32 females (M:F = 2.5:1). They showed a median age of 66.11 ± 9.98 years (ranging from 31 to 94 years), slightly lower (P = 0.05) in females (64.56 ± 11.18 years) than males (66.71 ± 9.47 years). All of the cases were diagnosed in stages pT1 (n = 52; 46.01%) or pT2 (n = 61; 53.99%). Regarding the tumor grade, 14 cases (12.38%) were diagnosed as G1, 64 (56.63%) as G2, 31 cases (27.43%) as G3, the other 4 cases (3.53%) being classified as G4 carcinomas. As for the associated hepatic lesions, we identified 47 cases (41.59%) developed in patients with cirrhosis, 39 patients (34.51%) had chronic persistent hepatitis, 23 (20.35%) showed Mallory bodies in absence of hepatitis, 34 (30.08%) were associated with steatosis, and 19 (16.81%) with cholestasis. From the 113 cases, 50 were randomly selected for angiogenesis assessment (Table 1).

Evaluation of COX-2 and VEGF-A expression in the 50 cases with HCC, revealed that the angiogenic immunophenotype of tumor cells, independently by the used antibody, was not correlated with the gender or age of the patient (Table 3). More than half of the cases showed a moderate (score 2+) expression of VEGF-A but COX-2 intensity was distributed in a similar manner, each third part of the cases revealing 1+, 2+ or 3+ intensity. No negative cases were identified.

| Parameter | COX-2 intensity | P value | VEGF-A intensity | P value | |||||

| 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | ||||

| n (%) | 14 (28) | 18 (36) | 18 (36) | 12 (24) | 28 (56) | 10 (20) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Males | 10 | 12 | 14 | 0.75 | 8 | 22 | 6 | 0.47 | |

| Females | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Age groups (yr) | |||||||||

| 31-50 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.33 | |

| 51-60 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 61-70 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 5 | |||

| 71-80 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 1 | |||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||

| G1+G2 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 0.006 | 6 | 19 | 7 | 0.50 | |

| G3+G4 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 3 | |||

| Tumor stage | |||||||||

| pT1 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 0.38 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 0.03 | |

| pT2 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 2 | |||

| Associated lesions | |||||||||

| With cirrhosis | 8 | 3 | 7 | 0.05 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 0.81 | |

| Without cirrhosis | 6 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 19 | 6 | |||

| With Mallory bodies | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0.05 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0.85 | |

| Without Mallory bodies | 7 | 13 | 16 | 8 | 21 | 7 | |||

| With hepatitis | 7 | 9 | 8 | 0.93 | 6 | 14 | 4 | 0.85 | |

| Without hepatitis | 7 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 6 | |||

Regarding tumor stage, COX-2 intensity did not show correlation with tumor size or multifocal aspect (pT stage). In solitary tumors smaller than 2 cm (pT1), VEGF-A presented a higher intensity (20 of the 23 cases showed 2+ or 3+ score of VEGF-A) than tumors with vascular invasion or multifocal aspect (pT2) (Table 3).

On the other hand, VEGF-A intensity was not correlated with tumor grade or the associated hepatic lesions. In contrast, COX-2 high intensity (score 2+ and 3+) was rather observed in dediferentiated carcinomas (G3+G4), whereas the G1+G2 cases showed an oscillating pattern of COX-2. The COX-2 expression was slightly elevated in patients that developed HCC in absence of premalignant lesions such hepatic cirrhosis or Mallory bodies (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Evaluation of EA showed that, independently of the antibody used for quantification of this angiogenic parameter (CD31 or CD105), it was not correlated with gender of patient, tumor stage or grade of differentiation (Table 4).

| Parameter | Number of cases | CD31-EA(median and range values) | P value | P value | |

| CD105-EA(median and range values) | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 36 | 7.35 ± 2.16 (2.57-11.18) | 0.31 | 8.91 ± 2.64 (4.06-15.53) | 0.44 |

| Females | 14 | 8.06 ± 2.30 (4.17-11.85) | 9.59 ± 3.28 (4.23-16.56) | ||

| Tumor grade | |||||

| G1+G2 | 32 | 7.69 ± 2.22 (2.57-11.69) | 0.53 | 9.28 ± 2.64 (4.06-16.56) | 0.55 |

| G3+G4 | 18 | 7.29 ± 2.21 (3.34-11.85) | 8.78 ± 3.17 (5.77-15.53) | ||

| Tumor stage | |||||

| pT1 | 23 | 7.85 ± 2.33 (2.57-11.69) | 0.59 | 9.47 ± 3.15 (4.06-16.56) | 0.39 |

| pT2 | 27 | 7.71 ± 2.11 (3.34-11.85) | 8.79 ± 2.51 (5.47-14.91) | ||

| Associated lesions | |||||

| With cirrhosis | 18 | 8.29 ± 1.68 (5.64-11.85) | 0.07 | 9.12 ± 2.51 (4.23-14.33) | 0.97 |

| Without cirrhosis | 32 | 7.13 ± 2.37 (2.57-11.69) | 9.09 ± 3.01 (4.06-16.56) | ||

| With Mallory bodies | 14 | 8.01 ± 1.39 (5.56-10.53) | 0.36 | 9.86 ± 2.89 (5.85-15.53) | 0.23 |

| Without Mallory bodies | 36 | 7.37 ± 2.44 (2.57-11.85) | 8.81 ± 2.77 (4.06-16.56) | ||

| With hepatitis | 24 | 7.28 ± 1.99 (2.57-10.53) | 0.40 | 8.26 ± 2.25 (4.23-12.28) | 0.04 |

| Without hepatitis | 26 | 7.80 ± 2.39 (3.07-11.85) | 9.88 ± 3.09 (4.06-16.56) |

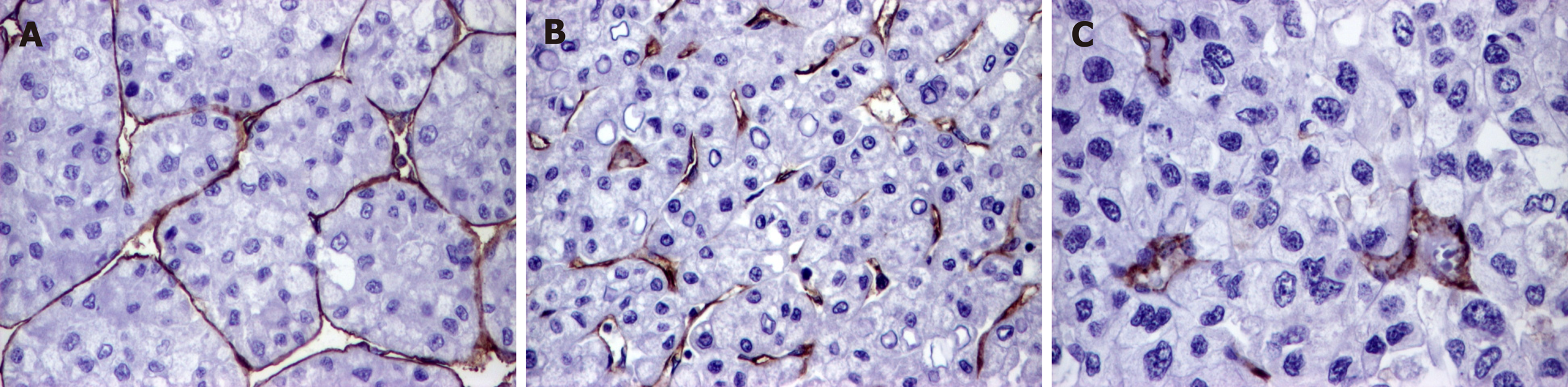

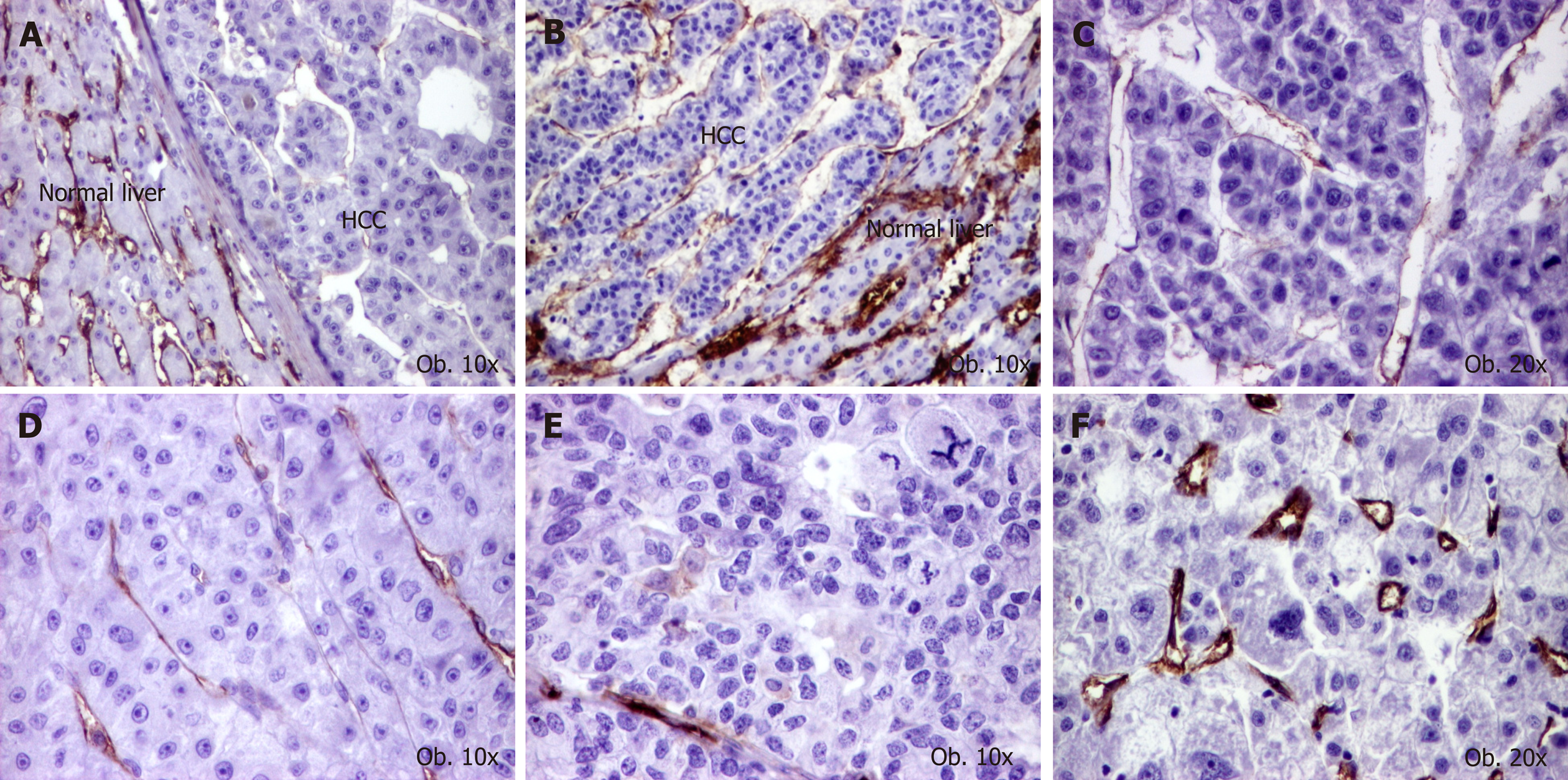

Regarding the associated lesions, a slightly elevated CD31-related EA was observed in tumors developed on the background of cirrhosis, whereas CD105-related EA was rather increased in cases without associated hepatitis (Table 4 and Figures 2 and 3).

COX-2 intensity increased in parallel with decreasing CD31-related EA. No correlation between CD105-EA value and CD31-EA, or COX-2 either VEGF-A intensity was observed (Table 5).

| COX-2 intensity | P value | VEGF-A intensity | P value | |||||

| 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | |||

| EA-CD31 | 8.66 ± 1.41 | 7.47 ± 2.29 | 6.76 ± 2.34 | 0.04 | 7.23 ± 1.52 | 7.53 ± 2.44 | 8.01 ± 2.32 | 0.72 |

| EA-CD105 | 9.22 ± 1.83 | 9.58 ± 3.56 | 8.53 ± 2.64 | 0.53 | 8.45 ± 1.74 | 8.95 ± 3.02 | 10.31 ± 3.15 | 0.28 |

The stepwise process of angiogenesis consists of releasing proteases by the activated endothelial cells, basal membrane degradation of the existing vessel, migration of the endothelial cells into the interstitial space, endothelial cells proliferation, and lumen formation[21]. However, the mechanism of formation of new vessels is still insufficiently known[21].

In HCCs, the pro-angiogenic VEGF-A is supposed to influence proliferation of tumor cells and endothelial cells[22-25]. At the same time, proliferated hepatocytes can release VEGF-A which binds to receptors (VEGF-R1/Flt-1, VEGF-R2/KDR, and VEGF-R3/Flt-4) that are localized within the tumor cells or on the surface of activated endothelial cells[3,24]. Despite this supposed mechanism, the anti-VEGF drugs such as bevacizumab (anti-VEGF-A) and ramucirumab (anti-VEGF-R2) or multi-tyrosine inhibitors such as sorafenib, regorafenib, lenvatinib or tivatinib, did not show encouraging results in all cases of HCC[18,19,26,27]. Morphological explanation of resistance is still unknown. It was recently supposed that angiogenesis might induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells[26], as a possible explanation of resistance to antiangiogenic drugs[19].

Regarding anti-COX therapy, in a meta-analysis published in 2018 it was shown that only 11 representative studies have been published about the controversial role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the occurrence and prognosis of HCC[9]. The conclusion of this meta-analysis was that NSAIDs decrease the risk of HCC occurrence and induce a better disease-free survival and overall survival, compared with non-NSAIDs users[9]. There were not differences between aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs users[9]. Moreover, in patients with HCC, aspirin did not increase the risk of bleeding[9]. However, it would be useful to identify morphological criteria of HCC cells that might select patients that could benefit by anti-VEGF versus anti-COX therapy. The commonly used dose of aspirin was 100 mg/d, for at least 90 consecutive days[9].

The morphological studies showed that, in peritumoral hepatocytes, both VEGF-A and COX-2 expression is higher than in tumor cells[2,28]. In our material, an oscillating pattern of VEGF-A was found in the HCC, independently from the tumor grade. In smaller tumors and those without vascular invasion, we also proved high VEGF-A intensity. The intensity decreased in parallel with tumor size and was also lower in cases with multiple nodules. Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) can upregulate VEGF-A[3], we did not find differences between VEGF expression in patients with or without hepatitis.

Regarding COX-2 expression, the literature data even indicates that COX-2 does not mediate the process of fibrosis[6,29,30], or, contrary, COX-2 plays roles in fibrogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis via metalloproteinases/mismatch repair proteins MMP-2 and MMP-9 or through activation of β-catenin[3], one of the mediators of epithelial mesenchymal transition[19]. Although COX-2 stimulates HCV replication and HCV stimulates COX-2 expression via oxidative stress[3], we did not find differences between COX-2 expression in patients with or without hepatitis. We proved that COX-2 induced tumor dedifferentiation in patients without cirrhosis and/or Mallory bodies.

The endothelial cells can be marked by CD31 but CD105 is more specific and marks only the activated cells. A high EA value is the expression of immature vessels, whereas predominance of mature vessels is quantified as a lower EA[21].

In our cases, mature vessels (low CD31-related EA) were predominant in COX-2 positive dedifferentiated HCCs, except those cases developed on a background of cirrhosis, which mostly showed immature vessels, and respectively a higher EA value[21]. In line to our data, it was experimentally shown that, although CD31 injection promotes migration of endothelial cells and HCC metastasis, it does influence intrahepatic metastases (pT stage)[26]. CD31 expression is higher in patients with associated cirrhosis and is mostly seen in tumor-derived endothelial cells[26]. CD31 reflects the rate of endothelization of sinusoids and extent of capillarization, which are characteristic features of HCC[31].

In contrast, the CD105-positive activated endothelial cells, mostly found in immature vessels[32,33], were more frequent in HCCs developed in the absence of hepatitis. Lack of correlation of EA/MVD with cirrhosis and tumor grade has also been observed by other authors[34]. As HCV might disturbe angiogenesis pathways and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis[3], it can be supposed that HCV might induce activation of endothelial cells and genesis of CD105 positive mature neoformed vessels.

As HCC is a heterogenous and frequent multifocal tumor, correlation with clinicopathological factors is difficult to be proved and literature data are controversial. Decreased MVD is supposed to be an indicator of poor prognosis[35,36]. Similar to our study, a lower MVD, respectively predominance of mature vessels, was shown in dediferentiated HCC[37,38]. The idea is not agreed by all authors, in some studies being showed that MVD is increased in dedifferentiated tumors of large sizes and in those associated with cirrhosis[39].

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the authors examined a small number of cases (n = 50). Although higher number of cases (but below 100) were analyzed in other studies[26,31], they were mostly performed using tissue microarrays slides. We have analyzed the angiogenesis in classic (full) slides, that confers the reproductibility character. Secondly, other cytokines and markers of epithelial mesenchymal transition[19] have been reported to be associated with HCC. The interaction of angiogenesis with these biomarkers should be explored in future studies.

In conclusion, based on the literature data and the present study, we can affirm that, in HCC, angiogenesis has an oscillating pattern but some specific features can be emphasized. In patients with cirrhosis, the newly formed vessels are rather immature, are syntesized via VEGF, and COX-2 is downregulated. The VEGF-A expression is rather high in first steps of carcinogenesis, respectively in small tumors that do not show vascular invasion. VEGF-A intensity decreases in advanced stages. In dedifferentiated HCCs, which were developed in absence of cirrhosis, COX-2 overexpression and predominance of mature vessels is characteristic.

Although hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one the most vascular solid tumors, mechanisms of angiogenesis are still unknown. Moreover, angiogenesis is not properly inhibited by the currently used chemotherapics. For these reasons, new data are necessary to be published regarding the angiogenesis background.

The aim of the study was to perform a complex immunohstochemical assessment of angiogenic immunophenotype pf HCC cells.

In this paper, we aimed to correlate the angiogenic immunophenotype of tumor cells with the values of endothelial area (EA). To reach the aim of the paper and understand the angiogenesis mechanisms, these two parameters were necessary to be examined.

The angiogenic immunophenotype of tumor cells was examined with the immunohisto-chemically antibodies Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A, whereas the values of EA were quantified using the antibodies CD31 and CD105. To increase the study reliability, the EA was digitally counted, using a semi automatically method.

The immunohistochemical study performed in this paper showed that the VEGF-A-related angiogenesis is more intense in small tumors, without vascular invasion, which were classified as pT1 HCCs. In the dedifferentiated and aggressive tumors, COX-2 was more expressed and CD31-related EA decreased, as result of proliferation of mature neoformed vessels. In patients with associated cirrhosis, CD31-related EA was higher, as result of proliferation of immature vessels. In patients without associated hepatitis, CD105-related EA was higher, as result of activated endothelial cells.

The original data identified in the present study showed that the antiangiogenic therapy do not show the expected results for several reasons: angiogenesis has an oscillating pattern, the mechanisms of inducing angiogenesis depend on the tumor size and grade of differentiation and the EA is not always a reflection of the angiogenesis intensity. Based on these data, it can be concluded that a targeted antiangiogenic therapy should be considered in patients with HCC, based on the pathways of induction angiogenesis in specific cases.

Before performing clinical trials with antiangiogenic/antityrosine-kinase drugs, the immunohistochemical and molecular background of the tumor tissue is mandatory to be checked in any patient. It should be tested, in experimental study, the theory of predominance of VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis in small differentiated HCCs and COX-2 induced angiogenesis and vascular maturation in dedifferentiated cases.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray. F. GLOBOCAN. 2012;IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013 [accessed on 20/05/2016] Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. |

| 2. | Turdean S, Gurzu S, Turcu M, Voidazan S, Sin A. Current data in clinicopathological characteristics of primary hepatic tumors. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2012;53:719-724. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mahmoudvand S, Shokri S, Taherkhani R, Farshadpour F. Hepatitis C virus core protein modulates several signaling pathways involved in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:42-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Liu K, Min XL, Peng J, Yang K, Yang L, Zhang XM. The Changes of HIF-1α and VEGF Expression After TACE in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:297-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhu B, Lin N, Zhang M, Zhu Y, Cheng H, Chen S, Ling Y, Pan W, Xu R. Activated hepatic stellate cells promote angiogenesis via interleukin-8 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2015;13:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liang R, Yan XX, Lin Y, Li Q, Yuan CL, Liu ZH, Li YQ. Functional polymorphisms of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma-a cohort study in Chinese people. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martín-Sanz P, Mayoral R, Casado M, Boscá L. COX-2 in liver, from regeneration to hepatocarcinogenesis: what we have learned from animal models? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1430-1435. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Takasu S, Tsukamoto T, Cao XY, Toyoda T, Hirata A, Ban H, Yamamoto M, Sakai H, Yanai T, Masegi T, Oshima M, Tatematsu M. Roles of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 expression and beta-catenin activation in gastric carcinogenesis in N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-treated K19-C2mE transgenic mice. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2356-2364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tao Y, Li Y, Liu X, Deng Q, Yu Y, Yang Z. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially aspirin, are linked to lower risk and better survival of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2695-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mattei MG, Borg JP, Rosnet O, Marmé D, Birnbaum D. Assignment of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placenta growth factor (PLGF) genes to human chromosome 6p12-p21 and 14q24-q31 regions, respectively. Genomics. 1996;32:168-169. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Murakami K, Kasajima A, Kawagishi N, Ohuchi N, Sasano H. Microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinoma: Prognostic significance and review of the previous published work. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:1185-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li Y, Ma X, Zhang J, Liu X, Liu L. Prognostic value of microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Biol Markers. 2014;29:e279-e287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gurzu S, Jung J, Azamfirei L, Mezei T, Cîmpean AM, Szentirmay Z. The angiogenesis in colorectal carcinomas with and without lymph node metastases. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2008;49:149-152. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Privratsky JR, Newman DK, Newman PJ. PECAM-1: conflicts of interest in inflammation. Life Sci. 2010;87:69-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pusztaszeri MP, Seelentag W, Bosman FT. Immunohistochemical expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34, von Willebrand factor, and Fli-1 in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:385-395. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Jung I, Gurzu S, Raica M, Cîmpean AM, Szentirmay Z. The differences between the endothelial area marked with CD31 and CD105 in colorectal carcinomas by computer-assisted morphometrical analysis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50:239-243. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Barriuso B, Antolín P, Arias FJ, Girotti A, Jiménez P, Cordoba-Diaz M, Cordoba-Diaz D, Girbés T. Anti-Human Endoglin (hCD105) Immunotoxin-Containing Recombinant Single Chain Ribosome-Inactivating Protein Musarmin 1. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Kasprzak A, Adamek A. Role of Endoglin (CD105) in the Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Anti-Angiogenic Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gurzu S, Turdean S, Kovecsi A, Contac AO, Jung I. Epithelial-mesenchymal, mesenchymal-epithelial, and endothelial-mesenchymal transitions in malignant tumors: An update. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:393-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abou-Alfa GK, Pawlik TM, Shindoh J, Vauthey JN. Liver. AJCC Cancer Staging manual. 2017;287-293. |

| 21. | Gurzu S, Cimpean AM, Kovacs J, Jung I. Counting of angiogenesis in colorectal carcinomas using double immunostain. Tumori. 2012;98:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park YN, Kim YB, Yang KM, Park C. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the early stage of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1061-1065. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lichtenberger BM, Tan PK, Niederleithner H, Ferrara N, Petzelbauer P, Sibilia M. Autocrine VEGF signaling synergizes with EGFR in tumor cells to promote epithelial cancer development. Cell. 2010;140:268-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shimizu H, Miyazaki M, Wakabayashi Y, Mitsuhashi N, Kato A, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Yoshidome H, Kataoka M, Nakajima N. Vascular endothelial growth factor secreted by replicating hepatocytes induces sinusoidal endothelial cell proliferation during regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats. J Hepatol. 2001;34:683-689. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Jain RK, Tong RT, Munn LL. Effect of vascular normalization by antiangiogenic therapy on interstitial hypertension, peritumor edema, and lymphatic metastasis: insights from a mathematical model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2729-2735. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Zhang YY, Kong LQ, Zhu XD, Cai H, Wang CH, Shi WK, Cao MQ, Li XL, Li KS, Zhang SZ, Chai ZT, Ao JY, Ye BG, Sun HC. CD31 regulates metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via the ITGB1-FAK-Akt signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2018;429:29-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Turkes F, Chau I. Ramucirumab and its use in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhu AX, Duda DG, Sahani DV, Jain RK. HCC and angiogenesis: possible targets and future directions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:292-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Soslow RA, Dannenberg AJ, Rush D, Woerner BM, Khan KN, Masferrer J, Koki AT. COX-2 is expressed in human pulmonary, colonic, and mammary tumors. Cancer. 2000;89:2637-2645. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Yu J, Wu CW, Chu ES, Hui AY, Cheng AS, Go MY, Ching AK, Chui YL, Chan HL, Sung JJ. Elucidation of the role of COX-2 in liver fibrogenesis using transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:571-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bösmüller H, Pfefferle V, Bittar Z, Scheble V, Horger M, Sipos B, Fend F. Microvessel density and angiogenesis in primary hepatic malignancies: Differential expression of CD31 and VEGFR-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1136-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yu D, Zhuang L, Sun X, Chen J, Yao Y, Meng K, Ding Y. Particular distribution and expression pattern of endoglin (CD105) in the liver of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:122. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Zhuang PY, Wang JD, Tang ZH, Zhou XP, Quan ZW, Liu YB, Shen J. Higher proliferation of peritumoral endothelial cells to IL-6/sIL-6R than tumoral endothelial cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yang LY, Lu WQ, Huang GW, Wang W. Correlation between CD105 expression and postoperative recurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:110. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Sun HC, Tang ZY, Li XM, Zhou YN, Sun BR, Ma ZC. Microvessel density of hepatocellular carcinoma: its relationship with prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1999;125:419-426. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Nanashima A, Nakayama T, Sumida Y, Abo T, Takeshita H, Shibata K, Hidaka S, Sawai T, Yasutake T, Nagayasu T. Relationship between microvessel count and post-hepatectomy survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4915-4922. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Asayama Y, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Nishihara Y, Aishima S, Tajima T, Hirakawa M, Ishigami K, Kakihara D, Taketomi A, Honda H. Poorly versus moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma: vascularity assessment by computed tomographic hepatic angiography in correlation with histologically counted number of unpaired arteries. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:188-192. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Asayama Y, Yoshimitsu K, Nishihara Y, Irie H, Aishima S, Taketomi A, Honda H. Arterial blood supply of hepatocellular carcinoma and histologic grading: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:W28-W34. [PubMed] |

| 39. | El-Assal ON, Yamanoi A, Soda Y, Yamaguchi M, Igarashi M, Yamamoto A, Nabika T, Nagasue N. Clinical significance of microvessel density and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and surrounding liver: possible involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor in the angiogenesis of cirrhotic liver. Hepatology. 1998;27:1554-1562. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed content statement: This is a retrospective study. No consent was necessary.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Chen G, Gorrell MD, Xiao E, Zhang Y S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL