Published online Nov 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i11.735

Peer-review started: August 22, 2019

First decision: September 20, 2019

Revised: September 28, 2019

Accepted: October 15, 2019

Article in press: October 15, 2019

Published online: November 27, 2019

Processing time: 77 Days and 15.1 Hours

Herbal supplements (HS) for weight loss are perceived to be “safe” and “natural”, as advertised in ads, however, hepatotoxicity can be associated with consumption of some HS. Use of HS may be missed, as the patient may not report these unless specifically asked about these products, since they are often not thought of as medications with potential side effects or interaction potential.

We reported a case of a 21-year-old female with morbid obesity who presented with abdominal pain for 1 wk associated with nausea, vomiting, anorexia and myalgias. She denied smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, usage of illicit drugs, hormonal contraceptives, or energy drinks. There was no significant past medical or family illnesses. Her laboratory workup revealed acute liver failure. The workup for possible etiologies of acute liver failure was unremarkable. She was using a weight loss herbal supplement “Garcinia cambogia” for 4 wks. This case demonstrates the association of acute liver failure with Garcinia cambogia.

Medical reconciliation of HS should be performed in patients with suspected acute liver failure and early discontinuation of HS can prevent further progression of drug induced hepatoxicity.

Core tip: Drug induced liver injury is a diagnosis of exclusion of possible etiologies of liver failure. Medical reconciliation of herbal supplements is important in these patients. The Council of International Organizations of Medical Sciences and Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method “CIOMS/RUCAM” scale is a useful tool for the assessment of drug induced liver injury. A high index of suspicion is required for identification of patients with drug induced liver failure. Early discontinuation of offending agent may prevent progression of disease and results in rapid recovery.

- Citation: Yousaf MN, Chaudhary FS, Hodanazari SM, Sittambalam CD. Hepatotoxicity associated with Garcinia cambogia: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(11): 735-742

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i11/735.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i11.735

In the United States, the prevalence of obesity is 39.8%, which is even higher among individuals aged 40 to 59 years old (42.8%)[1]. Individuals are using various modalities for weight loss including lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches. Herbal supplements (HS) have become a common method for weight loss due to accessibility without prescriptions, relatively low cost, and false perception of safety as widely advertised in the ads. Currently, there is lack of tight regulation of HS by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) which raises a concern for safety. Every year millions of American use over-the-counter herbal products and most of them are unaware of the potential harmful effects of these products. Among these individuals, 58% failed to report use of HS to their primary care providers[2]. Since they are often not viewed as medications with potential side effects, usage of these HS may be missed because patients may not report their use unless specifically asked about these products. The United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) noted increasing rates of hepatotoxicity due to HS in the past 10 years, ranging from 2%-16% of all reported liver injuries[3,4].

Garcinia cambogia (GC), a widely available “natural” HS, is found within a tropical fruit, commonly found in South Asia. Its extract is frequently used for weight loss and has been extensively marketed as such for the past decade. Herein we report a case of hepatotoxicity associated with use of the extract of GC.

A 21-year-old African American female with noted obesity (basic metabolic index 40.34 kg/m2), without significant past medical history, presented with abdominal pain for 1 wk.

Her abdominal pain was described as 7 out of 10 on a pain scale, diffuse, and non-radiating. It was associated with nausea, multiple episodes of non-biliary and non-bloody vomiting, anorexia, and myalgias. She denied any jaundice, pruritis, change in bowel habits, urinary symptoms, or extremity swelling. There was no history of fever, sick contacts, or recent blood transfusions.

There was no significant past medical illness.

She denied smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, usage of illicit drugs, hormonal contraceptives, or energy drinks. She mentioned that she was taking a HS, GC (1400 mg daily), for weight loss since 4 wks. Family history was unremarkable.

Vital signs were notable for tachycardia (133 bpm). On examination, she had epigastric and right upper quadrant tenderness, without jaundice or hepatosplenomegaly.

Laboratory workup (Table 1) revealed elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 981 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1062 U/L, alkaline phosphate 248 U/L, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.6, prothrombin time 19 s, and ammonia level 44 μmol/L. Acetaminophen and alcohol levels were negative, as was her urine toxicology. Testing for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus, parvovirus, and rapid plasma regain were negative. Autoimmune work-up including antinuclear antibody, antimitochondrial antibody, and anti-smooth muscle antibody were also negative. Serologies for alpha-1 antitrypsin, ceruloplasmin, iron studies, alpha fetoprotein, and carcinoembryonic antigen were unremarkable.

| Laboratory test | Reference range | Results |

| Liver function tests | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 15-41 U/L | 981 (H) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 3-34 U/L | 1062 (H) |

| Alkaline phosphate | 45-117 U/L | 248 (H) |

| Total bilirubin | 0.2-1.3 mg/dL | 1.3 (N) |

| Conjugated bilirubin | 0.0-0.30 mg/dL | 0.73 (H) |

| Total Protein | 6.3-8.2 g/dL | 6.8 (N) |

| Albumin | 3.5-5.0 g/dL | 2.8 (L) |

| Ammonia level | 0-32 μmol/L | 44 (H) |

| Coagulation Studies | ||

| Prothrombin time | 10-13.5 s | 19.0 (H) |

| International normalized ration | 0.8-1.2 | 1.6 (H) |

| Viral serologies | ||

| Hepatitis A, IgM | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Hepatitis A, IgG | Nonreactive | Reactive |

| Hepatitis B, core IgM | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Hepatitis B, surface antigen | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2 antibody/antigen | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 IgM | Negative | Negative |

| Cytomegalovirus, IgM | Negative | Negative |

| Cytomegalovirus, IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Epstein Barr virus, IgM | Negative | Negative |

| Parvovirus B19, IgM/IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Rapid plasma regain (RPR) | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Influenza A, antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Influenza B, antigen | Negative | Positive |

| Autoimmune liver disease panel | ||

| Antinuclear antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Antinuclear antibody titer | < 1.0 U | 0.6 (N) |

| Antismooth muscle antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Antimitochondrial antibody, M2 | < 0.1 U | < 0.1 (N) |

| Toxicology studies | ||

| Acetaminophen level | 10-30 mcg/ml | < 2 |

| Ethanol level | 0-3 mg/dL | < 3 |

| Urine toxicology screen | Negative | Negative |

Abdominal ultrasound showed hepatosplenomegaly with heterogenous increased echogenicity compatible with fatty liver. Abdominal computer tomography (CT) scan showed hepatosplenomegaly with heterogeneous-appearing liver.

The final diagnosis of presented case is acute liver failure associated with GC.

GC was stopped, and she was provided supportive care at the liver transplant center.

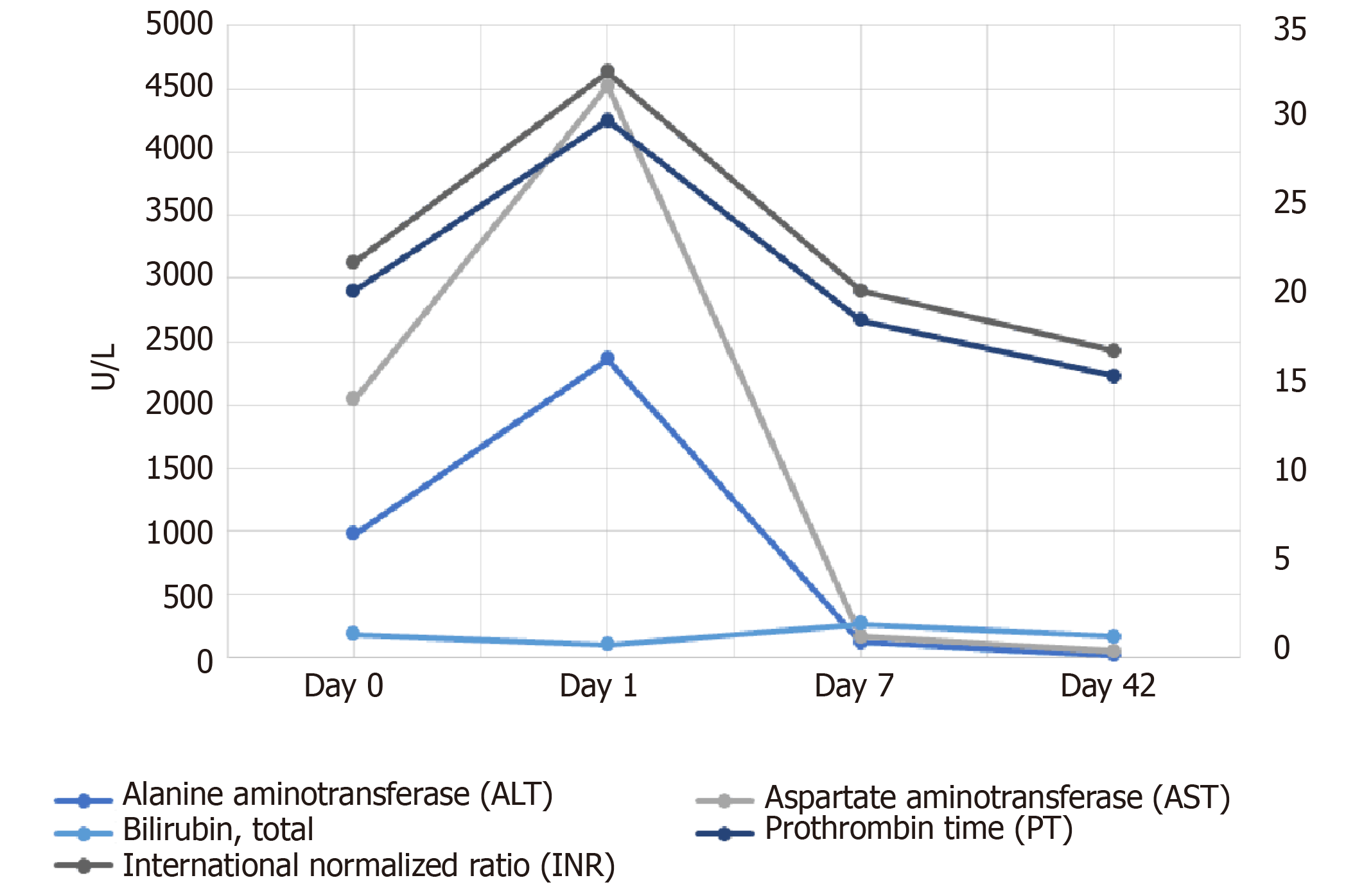

Patient’s symptoms resolved, and liver enzymes improved gradually (Figure 1) by day 7 (ALT 125 U/L, AST 46 U/L, alkaline phosphate 248 U/L). Her liver function test returned to her baseline at 42 days follow-up from discharge.

Herbal and dietary supplements are the second most common cause of drug-induced liver injury (DILI), after antibiotic therapy, in the United States[5]. Americans spend an estimated $66 billion annually on weight loss products[6]. Approximately 10% of obese population are using over-the-counter weight loss products in the Unites States[7]. HS are increasingly used for weight loss in the past decade, as these products are easily available over the counter and considered natural supplements without potential side effects. GC is one of the HS which is increasingly being used in the United States for weight loss. It contains hydroxycitric acid which is considered to be a “magical ingredient” responsible for weight loss. It affects the metabolism of citric acid cycle and inhibits the de novo synthesis of fatty acid[8].

“Hydroxycut” is a weight loss supplement which was commonly used for weight loss about a decade ago. GC was one of the active ingredients in Hydroxycut supplement. In April 2009, the FDA reported 23 cases of severe hepatotoxicity attributed to Hydroxycut[9] and issued a public warning in May 2009 causing Hydroxycut product to be recalled by its manufacturer. A reformulated form of Hydroxycut without GC extract was manufactured and reissued within the market for weight loss. Since May 2009, multiple case reports have identified the causal relationship of GC with severe hepatotoxicity (Table 2)[7,10-16]. These case reports reinforce the potential toxic effects of GC contributing to hepatotoxicity.

| Case report | Year | Age | Sex | Duration of GC use | Clinical presentation | CIOSM/RUCAM score | Liver transplantation |

| Present case | 2019 | 26 | Female | 28 d | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia and myalgia | 9 | No |

| Sharma et al[15] | 2018 | 57 | Female | 28 d | Vomiting and abdominal pain | 11 | No |

| Kothadia et al[14] | 2018 | 36 | Female | 28 d | Fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fatigue and jaundice | 8 | No |

| Lunsford et al[7] | 2016 | 34 | Male | 150 d | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and dark urine | NA | Yes |

| Smith et al[13] | 2016 | 26 | Male | 7 d | Fatigue, icteric sclera and skin | 6 | Yes |

| Corey et al[12] | 2016 | 52 | Female | 25 d | Fatigue, intermittent confusion and jaundice | 7 | Yes |

| Melendez-Rosado et al[11] | 2015 | 42 | Female | 7 d | Nausea, abdominal pain, clamminess | NA | No |

| Lee et al[16] | 2014 | 39 | Female | 2 d | Nausea, abdominal pain, anorexia, dyspepsia, fatigue and jaundice | 9 | No |

| Sharma et al[10] | 2010 | 19 | Male | NA | Fever, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, Nausea, Vomiting, abdominal pain and jaundice, erythematous skin rash lower extremities | 7 | No |

Due to multitude of ingredients in the supplement formulations, it is difficult to establish correlation of hepatotoxicity with GC. The exact mechanism by which it causes liver failure is unclear. A rodent study revealed that GC may exacerbate steatohepatitis by increasing hepatic collagen accumulation, lipid peroxidation, oxygen free radical injury, and levels of proinflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1[17]. The pattern of liver injury caused by GC was noted to be hepatocellular and cholestatic in most of the case reports (Table 2). The most common symptoms of presentation are nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, fatigue and generalized myalgias. The duration of GC use before onset of symptoms was ranged from 7 to 28 days however, it was found to be 2 days and 150 days in two case reports, respectively. In most patients, there was an improvement of symptoms and liver function with stopping GC and providing supportive care. Liver transplantation was required in 3 patients. In our case, the patient developed acute liver failure within 4 wks after starting GC. DILI is diagnosis of exclusion of other possible etiologies of acute liver failure, as was investigated in this patient.

To reduce the chances of overdiagnosis or misdiagnosis related to GC, The Council of International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scale is the “most commonly used scoring system to establish the etiology of DILI” (Table 3)[18]. The “CIOMS/RUCAM scale” grades DILI into definitive (score > 8), probable (score 6-8), possible (score 3-5), unlikely (score 1-2), or excluded (scores < 0). In this patient, a score of 9 was found and indicated acute liver failure secondary to use of herbal supplements. We excluded other possible etiologies of acute liver failure. Improvement in the patient’s symptoms and liver function with discontinuation of GC also indicated correlation of hepatotoxicity with GC.

| Criteria | Score |

| Time from drug intake until reaction onset | |

| 5-90 d | +2 |

| < 5 or > 90 d | +1 |

| Time from drug withdrawal until reaction onset | |

| < 15 d | +1 |

| > 15 d | 0 |

| Alcohol risk | |

| Present | +1 |

| Absent | 0 |

| Age | |

| > 55 yr | +1 |

| < 55 yr | 0 |

| Course of reaction | |

| > 50% improvement within 8 d | +3 |

| > 50% improvement within 30 d | +2 |

| Worsening or < 50% improvement in 30 d | -1 |

| Concomitant therapy | |

| Time to onset incompatible | 0 |

| Time to onset compatible but with unknown reaction | -1 |

| Time to onset compatible but known reaction Role proved in the case | -2 -3 |

| None or information not available | 0 |

| Exclusion of non-drug related causes | |

| Ruled out | +2 |

| Possible or not investigated | 0 |

| Probable | -3 |

| Previous information on hepatotoxicity | |

| Reaction unknown | 0 |

| Reaction published but unlabeled | +1 |

| Reaction labeled in the product’s characteristics | +2 |

| Response to re-administration | |

| Positive | +3 |

| Compatible | +2 |

| Negative | -2 |

| Not available or not interpretable | 0 |

| Plasma concentration of drug known as toxic | +3 |

| Validated laboratory test with high specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values positive | +3 |

| Validated laboratory test with high specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values negative | -3 |

| Interpretation of score for drug induced liver injury: | |

| > 8 definite drug induced liver injury | |

| 6-8 probable drug induced liver injury | |

| 3-5 Possible drug induced liver injury | |

| 1-2 Unlikely drug induced liver injury | |

| < 0 drug induced liver injury excluded |

Early recognition and discontinuation of GC can prevent progression of drug-induced liver failure to fulminant hepatic failure and the potential need for liver transplantation if not investigated and stopped rather quickly. Therefore, a medication reconciliation of both prescribed and over-the-counter supplements are prudent on an ongoing basis. Ingredients of herbal and dietary supplements should be regulated by FDA for adverse health consequences and safety profile; however, this may prove to be a daunting task given the number of HS that are on the market and continue to be developed. Further clinical trials are needed to recognize the association between GC and hepatotoxicity and whether this ingredient needs to be closely regulated, given its high propensity for detrimental and potentially fatal complications.

| 1. | Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief No. 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf. |

| 2. | Gardiner P, Graham R, Legedza AT, Ahn AC, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Factors associated with herbal therapy use by adults in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13:22-29. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dara L, Hewett J, Lim JK. Hydroxycut hepatotoxicity: a case series and review of liver toxicity from herbal weight loss supplements. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6999-7004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | García-Cortés M, Robles-Díaz M, Ortega-Alonso A, Medina-Caliz I, Andrade RJ. Hepatotoxicity by Dietary Supplements: A Tabular Listing and Clinical Characteristics. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Navarro VJ, Lucena MI. Hepatotoxicity induced by herbal and dietary supplements. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:172-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | The U. S. Weight Loss & Diet Control Market. Available from: https://www.marketresearch.com/Marketdata-Enterprises-Inc-v416/Weight-Loss-Diet-Control-10825677/. |

| 7. | Lunsford KE, Bodzin AS, Reino DC, Wang HL, Busuttil RW. Dangerous dietary supplements: Garcinia cambogia-associated hepatic failure requiring transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10071-10076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Heymsfield SB, Allison DB, Vasselli JR, Pietrobelli A, Greenfield D, Nunez C. Garcinia cambogia (hydroxycitric acid) as a potential antiobesity agent: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1596-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fong TL, Klontz KC, Canas-Coto A, Casper SJ, Durazo FA, Davern TJ 2nd, Hayashi P, Lee WM, Seeff LB. Hepatotoxicity due to hydroxycut: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1561-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sharma T, Wong L, Tsai N, Wong RD. Hydroxycut(®) (herbal weight loss supplement) induced hepatotoxicity: a case report and review of literature. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69:188-190. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Melendez-Rosado J, Snipelisky D, Matcha G, Stancampiano F. Acute hepatitis induced by pure Garcinia cambogia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:449-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Corey R, Werner KT, Singer A, Moss A, Smith M, Noelting J, Rakela J. Acute liver failure associated with Garcinia cambogia use. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Smith RJ, Bertilone C, Robertson AG. Fulminant liver failure and transplantation after use of dietary supplements. Med J Aust. 2016;204:30-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kothadia JP, Kaminski M, Samant H, Olivera-Martinez M. Hepatotoxicity Associated with Use of the Weight Loss Supplement Garcinia cambogia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Reports Hepatol. 2018;2018:6483605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Sharma A, Akagi E, Njie A, Goyal S, Arsene C, Krishnamoorthy G, Ehrinpreis M. Acute Hepatitis due to Garcinia Cambogia Extract, an Herbal Weight Loss Supplement. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:9606171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee JL, S. A Case of Toxic Hepatitis by Weight-Loss Herbal Supplement Containing Garcinia cambogia. Soonchunhyang Medical Science. 2014;20 (2):p. 96-98. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim YJ, Choi MS, Park YB, Kim SR, Lee MK, Jung UJ. Garcinia Cambogia attenuates diet-induced adiposity but exacerbates hepatic collagen accumulation and inflammation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4689-4701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Danan G, Teschke R. RUCAM in Drug and Herb Induced Liver Injury: The Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Manautou JE, Skrypnyk I S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ