Published online Feb 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i2.337

Peer-review started: November 28, 2017

First decision: December 18, 2017

Revised: January 10, 2018

Accepted: February 5, 2018

Article in press: February 5, 2018

Published online: February 27, 2018

Processing time: 96 Days and 4.6 Hours

To assess outcomes of kidney transplantation including patient and allograft outcomes in recipients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and the trends of patient’s outcomes overtime.

A literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Database from inception through October 2017. Studies that reported odds ratios (OR) of mortality or renal allograft failure after kidney transplantation in patients with HBV [defined as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive] were included. The comparison group consisted of HBsAg-negative kidney transplant recipients. Effect estimates from the individual study were extracted and combined using random-effect, generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird. The protocol for this meta-analysis is registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; no. CRD42017080657).

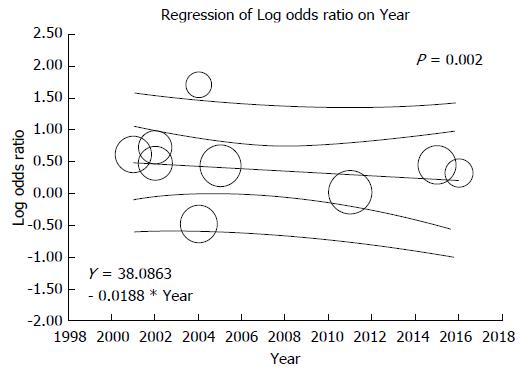

Ten observational studies with a total of 87623 kidney transplant patients were enrolled. Compared to HBsAg-negative recipients, HBsAg-positive status was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality after kidney transplantation (pooled OR = 2.48; 95%CI: 1.61-3.83). Meta-regression showed significant negative correlations between mortality risk after kidney transplantation in HBsAg-positive recipients and year of study (slopes = -0.062, P = 0.001). HBsAg-positive status was also associated with increased risk of renal allograft failure with pooled OR of 1.46 (95%CI: 1.08-1.96). There was also a significant negative correlation between year of study and risk of allograft failure (slopes = -0.018, P = 0.002). These associations existed in overall analysis as well as in limited cohort of hepatitis C virus-negative patients. We found no publication bias as assessed by the funnel plots and Egger’s regression asymmetry test with P = 0.18 and 0.13 for the risks of mortality and allograft failure after kidney transplantation in HBsAg-positive recipients, respectively.

Among kidney transplant patients, there are significant associations between HBsAg-positive status and poor outcomes including mortality and allograft failure. However, there are potential improvements in patient and graft survivals in HBsAg-positive recipients overtime.

Core tip: Hepatitis B is one of the most common infectious diseases worldwide. Despite advances in medicine, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is currently incurable. In addition, clinical outcomes of kidney transplantation in HBV infected patients are still unclear. To further assess these outcomes, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to assess patient and allograft outcomes after kidney transplantation in patients with HBV Infection. We found significant associations between HBV positive status and poor outcomes including 2.5-fold increased risk of mortality and 1.5-fold increased risk of allograft loss.

- Citation: Thongprayoon C, Kaewput W, Sharma K, Wijarnpreecha K, Leeaphorn N, Ungprasert P, Sakhuja A, Cabeza Rivera FH, Cheungpasitporn W. Outcomes of kidney transplantation in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(2): 337-346

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i2/337.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i2.337

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the most common infectious diseases and major health problems worldwide[1-3]. In 2017, approximately 257 million people have chronic hepatitis B virus infection[1]. Despite advances in medicine which have resulted in a cure for hepatitis C infection in recent years[4], chronic HBV infection is still currently considered as an incurable disease[2,3,5], leading to significant mortality (887000 death in 2015) and morbidities including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[1,2].

Advances in immunosuppression and kidney transplant techniques have led to significant improvements in short-term survival of the renal allograft[6]. Long-term graft survival, however, has remained relatively lagged behind and has now become one of the main problems in kidney transplantation[7-9]. Although HBV is preventable disease by HBV vaccine, HBV infection remains a challenge issue in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis, affecting from 1.3% up to 14.6% of chronic dialysis patients [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) –positive] depending on geographical regions[10-12], and, consequently leading to chronic HBV infection kidney transplant patients[13-31]. Among renal transplant patients with HBV (HBsAg positive), there have been reported cases of HBV reactivation[32], massive liver necrosis due to fulminant hepatitis, and severe cholestatic hepatitis after kidney transplantation[10,16,33-36]. In addition, chronic HBV infection may result in HBV-related membranous nephropathy after kidney transplantation[37-43].

Even though HBV is incurable, current more available antiviral agents against HBV effectively suppress viral replication[10]. Thus, these agents can prevent hepatic fibrosis[10] and potentially reduce significant hepatic and extra-hepatic complications related to chronic HBV. In spite of improvement of HBV care, outcomes of kidney transplantation including patient and allograft outcomes in recipients with HBV infection remain unclear. Thus, we conducted this meta-analysis to (1) Assess the risks of mortality and allograft failure in kidney transplant recipients with HBsAg-positive status; and (2) evaluate trends of patient’s outcomes overtime.

The protocol for this meta-analysis is registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; no. CRD42017080657). A systematic literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from database inception to October 2017 was conducted to identify studies assessing outcomes of kidney transplantation including patient and allograft outcomes in patients with HBV. The systematic literature review was undertaken independently by two investigators (C.T. and W.C.) applying the search approach that incorporated the terms of “hepatitis B” or “HBV”, or “viral hepatitis” and “kidney transplantation” which is provided in online supplementary data 1. No language limitation was applied. A manual search for conceivably relevant studies using references of the included articles was also performed. This study was conducted by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement[44] and previously published guidelines[45,46].

Eligible studies must be randomized controlled trials or observational studies including cohort studies, case-control, or cross-sectional that assessed the risks of mortality and/or allograft loss after kidney transplantation in patients with HBV (HBsAg-positive). They must provide the effect estimates odds ratios (OR), relative risks (RR), or hazard ratios (HR) with 95%CI. The comparison group consisted of HBsAg-negative kidney transplant recipients. Retrieved articles were individually reviewed for their eligibility by the two investigators (C.T. and W.C.) noted previously. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by mutual consensus. Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to appraise the quality of study for case-control study and outcome of interest for cohort study[47]. The modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used for cross-sectional study[48], as shown in Table 1.

| Study | Lee et al[55] | Breitenfeldt et al[56] | Chan et al[21] | Morales et al[57] | Ridruejo et al[52] | Aroldi et al[53] | Yap et al[18] | Reddy et al[36] | Grenha et al[31] | Lee et al[54] |

| Country | Taiwan | Germany | Hong Kong | Spain | Argentina | Italy | Hong Kong | USA | Portugal | Korea |

| Study design | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort study | Cohort | Cohort study | Cohort study |

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2002 | 2004 | 2004 | 2005 | 2010 | 2011 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Total number | 477 | 927 | 509 | 3365 | 231 | 541 | 126 | 75681 | 2284 | 3482 |

| Age (yr) | 38.6 ± 11.5 | 41.7 | N/A | 45.6 ± 13.0 | 38 | 31.7 | 49.2 | N/A | 44.3 | 40.6 ± 12.9 |

| Male | 280 (58.7%) | 595 (64.2%) | N/A | 2119 (63.0%) | 136 (58.9%) | 322 (59.5%) | 90 (71.4%) | 45249 (59.8%) | 1524 (66.7%) | 2084 (59.9%) |

| Living donor | N/A | 19 (2.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 62 (11.5%) | 41 (32.5%) | 32096 (42.4%) | 80 (3.5%) | 2571 (73.8%) |

| HBsAg | 62 (13.0%) | 37 (4.0%) | 67 (13.2%) | 76 (2.2%) | 17 (7.3%) | 77 (14.2%) | 63 (50%) | 1346 (1.8%) | 76 (3.3%) | 160 (4.6%) |

| HBeAg in HbsAg (+) patients | N/A | 11/37 (29.7%) | 29/67 (43.3%) | N/A | N/A | 34/77 (44.2%) | 16/63 (25.4%) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HBV treatment | N/A | N/A | Lamivudine 26/67 (39%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lamivudine 38/63 (60%) | N/A | N/A | Not specified 129/160 (81%) |

| Anti-HCV | 151 (31.7%) | 130 (14.0%) | 0 (0%) | 513 (15.2%) | 106 (45.9%) | 244 (45.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 113 (4.9%) | 55/3482 (1.6%) |

| Immunosuppression | Cyclosporine, steroid, azathioprine, MMF | N/A | Cyclosporine, steroid, azathioprine | Cyclosporine, steroid, azathioprine, MMF, FK506 | Cyclosporine, steroid, azathioprine | Cyclosporine, steroid, azathioprine | Cyclosporine/tacrolimus, steroid, MMF | Cyclosporine/tacrolimus, steroid, azathioprine, MMF, mTOR | N/A | Cyclosporine/tacrolimus, steroid, azathioprine/MMF |

| Follow-up after KTx | 6.0 ± 7.0 yr | 9.2 ± 4.4 yr | 82 ± 58 mo | N/A | 39.9 (1-10.4.2) mo | 11 yr | 140.1 mo | 1098 d | 10 yr | 89.1 ± 54.1 mo |

| Mortality | Overall | Overall | No HCV | Overall | Overall | Overall | No HCV | Overall | Overall | 2.37 (1.16-4.87) |

| 2.72 (1.48-4.99) | 4.08 (2.10-7.93) | 8.07 (3.65-17.86) | 2.06 (1.24-3.40) | 2.20 (0.57-8.34) | 2.36 (1.50-3.70) | 11.70 (1.45-94.40) | 1.07 (0.88-1.31) | 1.33 (0.78-2.29) | ||

| No HCV | No HCV | No HCV | No HCV | Living donor | No HCV | |||||

| 4.61 (2.41-8.84) | 3.60 (1.72-7.54) | 2.97 (1.66-5.33) | 4.40 (2.06-9.41) | 0.98 (0.59-1.63) | 1.02 (0.54-1.94) | |||||

| Deceased donor | ||||||||||

| 1.09 (0.88-1.36) | ||||||||||

| Graft failure | Overall | Overall | No HCV | Overall | 5.45 (1.95-15.23) | Overall | N/A | Overall | Overall | 1.38 (0.55-3.50) |

| 1.84 (1.08-3.15) | 2.07 (1.06-4.05) | 1.61 (0.86-3.03) | 0.62 (0.37-1.02) | 1.55 (1.12-2.14) | 1.02 (0.81-1.28) | 1.57 (0.99-2.49) | ||||

| No HCV | No HCV | No HCV | No HCV | Living donor | No HCV | |||||

| 3.56 (1.89-6.71) | 1.48 (0.71-3.08) | 0.59 (0.32-1.09) | 0.65 (0.27-1.54) | 0.90 (0.62-1.30) | 1.63 (0.98-2.71) | |||||

| Deceased donor | ||||||||||

| 1.10 (0.82-1.47) | ||||||||||

| Confounder adjustment | None | None | None | None | None | Age, Hepatitis C status | none | Recipient age, gender, BMI, race, comorbid, dialysis duration, donor HBcAb, expanded criteria donor, HLA DR mismatch, cold ischemia time, induction therapy, immunosuppressants | none | Age, sex, DM, BMI, primary renal disease, donor type, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, immunosuppressive agents |

| New Castle-Ottawa score | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 | S 4 |

| C 0 | C 0 | C 0 | C 0 | C 0 | C 1 | C 0 | C 2 | C 0 | C 2 | |

| O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 | O 3 |

A structured data collecting form was used to derive the following information from each study including title, year of the study, name of the first author, publication year, country where the study was conducted, demographic and characteristic data, mean age, patient’s sex, donor type, % of patients with HBeAg, % of patients with coexist patients infected with hepatitis C virus, and adjusted effect estimates with 95%CI and covariates that were adjusted in the multivariable analysis.

Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 3; Biostat Inc) was used to analyze the data. Adjusted point estimates from each study were consolidated by the generic inverse variance approach of DerSimonian and Laird, which designated the weight of each study based on its variance[49]. Given the likelihood of increased inter-observation variance; a random-effect model was utilized to assess the pooled prevalence and pooled OR with 95%CI for the risks of atrial fibrillation with sleep duration, insomnia, and frequent awakening. Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic were applied to determine the between-study heterogeneity. A value of I2 of 0-25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, 26%-50% represents low heterogeneity, 51%-75% represents moderate heterogeneity, and > 75% represents high heterogeneity[50]. The presence of publication bias was evaluated via the Egger test[51].

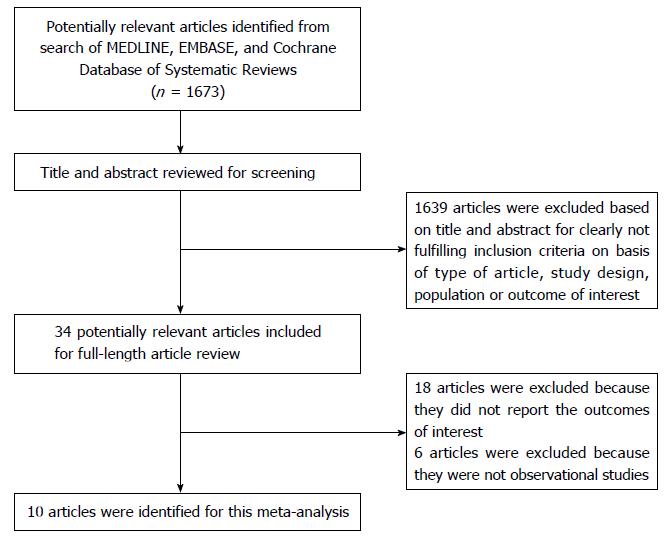

A total of 1673 potentially eligible articles were identified using our search strategy. After the exclusion of 1639 articles based on the title and abstract for clearly not fulfilling inclusion criteria on the basis of the type of article, study design, population or outcome of interest, leaving 34 articles for full-length review. Eighteen of them were excluded from the full-length review as they did not report the outcome of interest while six articles were excluded because they were descriptive studies without comparative analysis. Thus, the final analysis included 10 cohort studies[18,21,31,36,52-57] with 87623 kidney transplant patients. The literature retrieval, review, and selection process are demonstrated in Figure 1. The characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Patients in most included studies used calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression. Mean age was between the ages of 32-49.

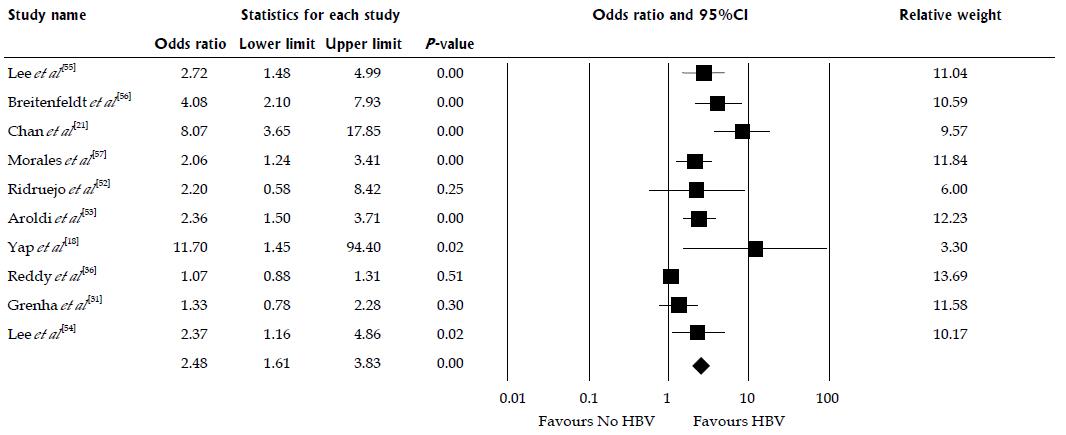

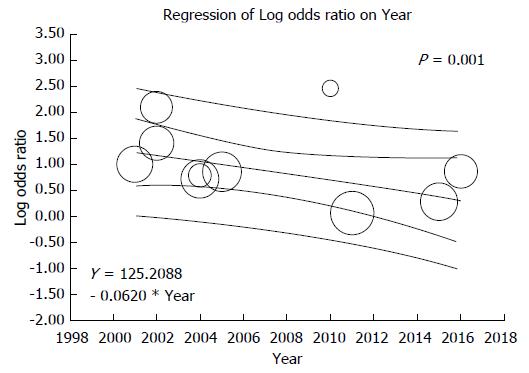

Ten studies assessed the mortality risk after kidney transplantation in patients with HBV as shown in Table 1. Compared to HBsAg-negative patients, HBsAg-positive status was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality after kidney transplantation (pooled OR = 2.48; 95%CI: 1.61-3.83, I2 = 82, Figure 2). When meta-analysis was limited only to non-HCV patient population, the pooled OR of mortality was 2.98 (95%CI: 1.47-6.07, I2 = 89). When meta-analysis was limited only to studies with adjusted analysis for confounders[36,53,54], the pooled OR of mortality was 1.27 (95% CI: 1.06-1.51, I2 = 85). Meta-regression showed significant negative correlations between mortality risk after kidney transplantation in HBsAg-positive patients and year of study (slopes = -0.062, P = 0.001, Figure 3). Meta-regression showed no significant impact of donor type on the association between HBsAg-positive status and increased risk of mortality after kidney transplantation (P = 0.11).

Of 10 studies[18,21,31,36,52-57], 3 studies[18,21,54] provided data on prophylactic antiviral treatment for HBV. When meta-analysis was limited only to studies with HBsAg-positive recipients (> 50%) treated with prophylactic antiviral treatment for HBV, the pooled OR of mortality was 3.85 (95%CI: 0.91-16.23, I2 = 50%). In a recent study by Lee et al[54], which 81% of HBs Ag-positive recipients were treated with prophylactic antiviral treatment, HBsAg-positive status was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality after kidney transplantation with adjusted HR of 2.37 (95%CI: 1.16-4.87).

Yap et al[18] demonstrated that recipients treated with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues had significantly better patient survival, when compared to those who were not on treatment (83% vs 34% at 20 years, P = 0.006). In patients who had lamivudine-resistant HBV, the investigators showed that treatment with adefovir or entecavir was effective with a three-log reduction in HBV DNA by 6 mo. When compared to patients who were treated with lamivudine or adefovir, Lee et al[54] demonstrated that those treated with new generation antiviral agent entecavir had better patient survival (log-rank, P = 0.050).

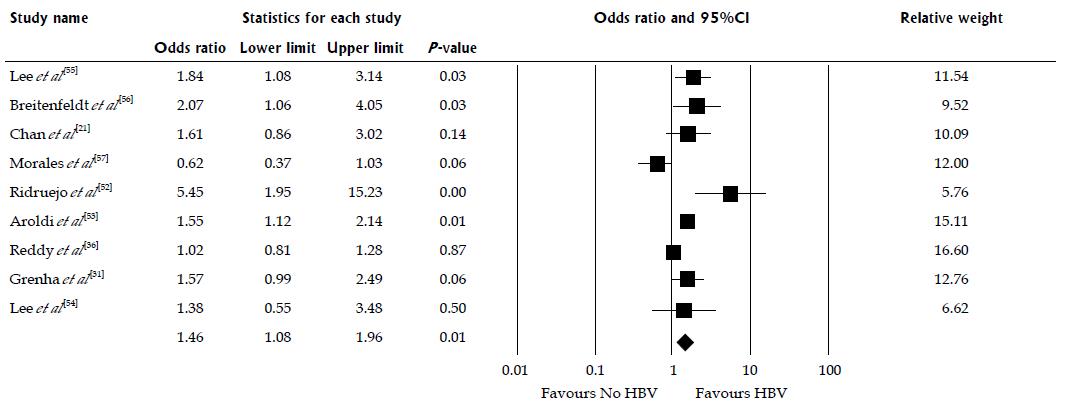

There were 9 studies assessed renal allograft outcomes in HBsAg-positive patients (Table 1). HBsAg-positive status was significantly associated with increased risk of renal allograft loss with pooled OR of 1.46 (95%CI: 1.08-1.96, I2 = 69, Figure 4). When meta-analysis was limited only to non-HCV patient population, the pooled OR of allograft failure was 1.33 (95%CI: 1.00-1.77, I2 = 80). When meta-analysis was limited only to studies with adjusted analysis for confounders[36,53,54], the pooled OR of allograft failure was 1.25 (95%CI: 0.90-1.73, I2 = 54). There was also a significant negative correlation between year of study and risk of allograft failure (slopes = -0.018, P =0.002, Figure 5). Meta-regression showed no significant impact of donor type on the association between HBsAg-positive status and increased risk of renal allograft loss (P =0.52).

We found no publication bias as assessed by the funnel plots (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2) and Egger’s regression asymmetry test with P = 0.18 and 0.13 for the risks of mortality and allograft failure after kidney transplantation in HBV infected patients, respectively.

In this systematic review, we demonstrated that HBsAg-positive status in kidney transplant recipients was significantly associated with poor outcomes after transplantation including a 2.5-fold increased risk of mortality and 1.5-fold increased risk of allograft loss. Theses associations existed in overall analysis as well as in limited cohort of hepatitis C virus-negative patients.

Chronic HBV infection can negatively impact the clinical outcomes of kidney allograft recipients. Compared to the HBsAg-negative recipients, HBsAg-positive recipients carry a higher risk of hepatic complications including chronic hepatitis, liver failure, fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[34,36,58]. In addition, some immunosuppressive agents after kidney transplantation may also put patients at higher risks of HBV reactivation[23,40]. HBV genome contains glucocorticoid responsive element that activates transcription of HBV genes[35]. Moreover, cyclosporine may also enhance HBV replication, leading to higher risks of HBV-related complications in kidney transplant recipients[37]. Previously, in 2005, Fabrizi et al[27] conducted a meta-analysis of six observational studies and demonstrated a significant association between HBsAg seropositive status and increased mortality after kidney transplantation. Since then, although hepatitis B is still incurable, there have been significant advancements in antiviral agents including the United States Food and Drug Administration approvals of entecavir in 2005 and telbivudine in 2006[59] resulting in reasonably sustained suppression of HBV replication after kidney transplantation[10]. Our meta-analysis with a new era of medicine also demonstrated a 2.7-fold increased risk of mortality in kidney transplant recipients with HBsAg positivity, when compared to HBsAg-negative recipients. In addition, our meta-analysis is the first to demonstrate a significant negative correlation between the mortality risk and year of study, which potentially represents improvements in patient care and management for chronic HBV in kidney transplant patients[60]. Although antiviral treatment has been shown to reduce mortality after kidney transplantation due to decrease in liver complications[18,21,54], in the era of antiviral therapies, Lee et al[54] recently showed that deaths from liver complications remained a significant problem accounting for 40% of deaths in HBsAg patients and 22.2% of all mortalities that occurred in recipients treated with antiviral agents[54].

There are several plausible explanations for the increased risk of renal allograft failure in recipients with HBsAg-positivity. Firstly, it is known that chronic HBV infection can result in HBV-related membranous nephropathy, not only in patients with native kidneys but also in kidney transplant recipients[37-43]. Secondly, due to a concern of HBV reactivation, physicians may avoid or limit the use particular immunosuppression or Rituximab in HBsAg-positive patients when it is indicated such as for recurrent glomerulonephritis post-transplantation[61,62]. Lastly, treatment of chronic HBV infection itself such as tenofovir could affect renal function[63]. Thus, the findings from our meta-analysis confirm an increased risk of allograft failure in HBsAg seropositive patients, when compared to HBsAg-negative recipients. Also, we found a significant negative correlation between the risk of allograft failure in HBsAg positive patients and year of study. Recently, data analysis from the Organ Procurement Transplant Network/United Network for Organ Sharing database (OPTN/UNOS) suggested no increased risk for allograft failure or death in HBV-infected kidney transplant patients in a recent era (between 2001 and 2007)[36]. Although follow-up time was limited to only 3 years post-transplant, these data along with the findings from our study suggest potential improvements in patient and graft survivals in HBsAg-positive recipients overtime.

There are several limitations in this meta-analysis that bear mentioning. First, there was low to moderate statistical heterogeneity between studies in meta-analysis assessing the risks of mortality and allograft failure in HBsAg-positive recipients. The possible source of this heterogeneity includes the difference in population, type of donor, number of patients with positive HBeAg, immunosuppression regimens, and difference in confounder adjustments. In addition, the data on the graft quality (e.g., Kidney Donor Profile Index) and surgical technique in HBsAg-positive recipients were limited. Second, despite the associations of HBsAg-positive status with poor kidney transplant outcomes, there is limited evidence whether the treatment with antiviral drugs for chronic HBV helps improve patient and allograft survival. However, with potential improvements in patient and graft survivals overtime demonstrated in our meta-analysis, future studies are required to evaluate if advancement in patient care for chronic HBV plays an important role. Also, additional studies are required to identify optimal antiviral treatment regimens and duration of suppressive therapy for HBV after kidney transplantation, since outcomes after withdrawal of antiviral treatment in kidney transplant recipients with chronic HBV infection remain unknown. While cautious withdrawal of antiviral therapy post kidney transplantation has been described especially in those with stable renal allograft function, low immunological risk for rejection and no evidence for HBV activity[10,23], fatal hepatitis flares in several kidney transplant recipients have been reported after withdrawal of antiviral therapy[64]. Lastly, this is a meta-analysis of observational studies. Thus, it can at best identify only associations of HBsAg-positive status with poor kidney transplant outcomes, but not a causal relationship.

In summary, our study reveals an association between HBsAg-positive status in kidney transplant recipients and higher risks of mortality and allograft failure after kidney transplantation. However, there are also significant negative correlations between the risks of mortality and allograft failure and year of study, representing potential improvements in patient and graft survivals overtime.

Among renal transplant patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) (HBsAg positive), there have been reported cases of HBV reactivation, massive liver necrosis due to fulminant hepatitis, and severe cholestatic hepatitis after kidney transplantation. In spite of improvement of HBV care, the outcomes of kidney transplantation including patient and allograft outcomes in recipients with HBV infection remain unclear.

Although hepatitis B is still incurable, there have been significant advancements in antiviral agents resulting in reasonably sustained suppression of HBV replication after kidney transplantation. The results of studies on kidney transplant outcomes in patients with renal transplant patients with HBV (HBsAg positive) were inconsistent. To further investigate outcomes of renal transplant patients with HBsAg positivity, the authors conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis reporting the association between HBsAg positivity in kidney transplant recipients and higher risks of mortality and allograft failure after kidney transplantation.

We conducted this meta-analysis to assess the outcomes of kidney transplantation including patient and allograft outcomes in recipients with HBV infection; and the trends of patient’s outcomes overtime.

A literature search was conducted using databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Database) from inception through October 2017. Those studies reported odds ratios (OR) of mortality or renal allograft failure after kidney transplantation in HBV patients (defined as HBsAg positive) were included. HBsAg-negative kidney transplant recipients are the comparison group. The effect estimates from the individual study were extracted and combined.

The authors demonstrated that HBsAg-positive status in kidney transplant recipients was significantly associated with poor outcomes after transplantation. These associations existed in overall analysis as well as in limited cohort of hepatitis C virus-negative patients.

The authors found significant associations of HBsAg positive status with poor outcomes after transplantation. Significant negative correlations between the risks of mortality and allograft failure and year of study, representing potential improvements in patient and graft survivals overtime were found.

This study demonstrated significantly increased risks of mortality and allograft failure in HBsAg-positive kidney transplant recipients. This finding suggests that HBsAg positive status may be an independent potential risk factor for poor outcomes after transplantation. However, there are also potential improvements in patient and graft survivals with HBV infection overtime.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/. |

| 2. | Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1532] [Cited by in RCA: 1631] [Article Influence: 163.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 2057] [Article Influence: 205.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 4. | AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 998] [Article Influence: 90.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ, Brown RS Jr, Wong JB, Ahmed AT, Farah W, Almasri J, Alahdab F, Benkhadra K, Mouchli MA, Singh S, Mohamed EA, Abu Dabrh AM, Prokop LJ, Wang Z, Murad MH, Mohammed K. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B viral infection in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63:284-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hariharan S, Johnson CP, Bresnahan BA, Taranto SE, McIntosh MJ, Stablein D. Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the United States, 1988 to 1996. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1431] [Cited by in RCA: 1444] [Article Influence: 55.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Kaplan B. Long-term renal allograft survival: have we made significant progress or is it time to rethink our analytic and therapeutic strategies? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1289-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:450-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 664] [Cited by in RCA: 708] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schinstock CA, Stegall M, Cosio F. New insights regarding chronic antibody-mediated rejection and its progression to transplant glomerulopathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:611-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marinaki S, Kolovou K, Sakellariou S, Boletis JN, Delladetsima IK. Hepatitis B in renal transplant patients. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:1054-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18:52-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johnson DW, Dent H, Yao Q, Tranaeus A, Huang CC, Han DS, Jha V, Wang T, Kawaguchi Y, Qian J. Frequencies of hepatitis B and C infections among haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Asia-Pacific countries: analysis of registry data. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1598-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Filik L, Karakayali H, Moray G, Dalgiç A, Emiroğlu R, Ozdemir N, Colak T, Gür G, Yilmaz U, Haberal M. Lamivudine therapy in kidney allograft recipients who are seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:496-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lai HW, Chang CC, Chen TH, Tsai MC, Chen TY, Lin CC. Safety and efficacy of adefovir therapy for lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection in renal transplant recipients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fontaine H, Vallet-Pichard A, Chaix ML, Currie G, Serpaggi J, Verkarre V, Varaut A, Morales E, Nalpas B, Brosgart C. Efficacy and safety of adefovir dipivoxil in kidney recipients, hemodialysis patients, and patients with renal insufficiency. Transplantation. 2005;80:1086-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chopra B, Sureshkumar KK. Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Exposed to Hepatitis B Virus: Analysis by Phase of Infection. Transplant Proc. 2017;49:278-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kamar N, Milioto O, Alric L, El Kahwaji L, Cointault O, Lavayssière L, Sauné K, Izopet J, Rostaing L. Entecavir therapy for adefovir-resistant hepatitis B virus infection in kidney and liver allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2008;86:611-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yap DY, Tang CS, Yung S, Choy BY, Yuen MF, Chan TM. Long-term outcome of renal transplant recipients with chronic hepatitis B infection-impact of antiviral treatments. Transplantation. 2010;90:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Daudé M, Rostaing L, Sauné K, Lavayssière L, Basse G, Esposito L, Guitard J, Izopet J, Alric L, Kamar N. Tenofovir therapy in hepatitis B virus-positive solid-organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;91:916-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nho KW, Kim YH, Han DJ, Park SK, Kim SB. Kidney transplantation alone in end-stage renal disease patients with hepatitis B liver cirrhosis: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 2015;99:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chan TM, Fang GX, Tang CS, Cheng IK, Lai KN, Ho SK. Preemptive lamivudine therapy based on HBV DNA level in HBsAg-positive kidney allograft recipients. Hepatology. 2002;36:1246-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chan TM, Tse KC, Tang CS, Lai KN, Ho SK. Prospective study on lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1103-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cho JH, Lim JH, Park GY, Kim JS, Kang YJ, Kwon O, Choi JY, Park SH, Kim YL, Kim HK. Successful withdrawal of antiviral treatment in kidney transplant recipients with chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pattullo V. Prevention of Hepatitis B reactivation in the setting of immunosuppression. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22:219-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pattullo V. Hepatitis B reactivation in the setting of chemotherapy and immunosuppression - prevention is better than cure. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:954-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lampertico P, Viganò M, Facchetti F, Invernizzi F, Aroldi A, Lunghi G, Messa PG, Colombo M. Long-term add-on therapy with adefovir in lamivudine-resistant kidney graft recipients with chronic hepatitis B. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2037-2041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Kanwal F, Dulai G. HBsAg seropositive status and survival after renal transplantation: meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2913-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jiang H, Wu J, Zhang X, Wu D, Huang H, He Q, Wang R, Wang Y, Zhang J, Chen J. Kidney transplantation from hepatitis B surface antigen positive donors into hepatitis B surface antibody positive recipients: a prospective nonrandomized controlled study from a single center. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1853-1858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fabrizi F, Dulai G, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Martin P. Lamivudine for the treatment of hepatitis B virus-related liver disease after renal transplantation: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Transplantation. 2004;77:859-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tsai MC, Chen YT, Chien YS, Chen TC, Hu TH. Hepatitis B virus infection and renal transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3878-3887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Grenha V, Parada B, Ferreira C, Figueiredo A, Macário F, Alves R, Coelho H, Sepúlveda L, Freire MJ, Retroz E. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and kidney transplant acute rejection and survival. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:942-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sezgin Göksu S, Bilal S, Coşkun HŞ. Hepatitis B reactivation related to everolimus. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yap DY, Chan TM. Evolution of hepatitis B management in kidney transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:468-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shah AS, Amarapurkar DN. Spectrum of hepatitis B and renal involvement. Liver Int. 2018;38:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Reddy PN, Sampaio MS, Kuo HT, Martin P, Bunnapradist S. Impact of pre-existing hepatitis B infection on the outcomes of kidney transplant recipients in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1481-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yagisawa T, Toma H, Tanabe K, Ishikawa N, Tokumoto N, Iguchi Y, Goya N, Nakazawa H, Takahashi K, Ota K. Long-term outcome of renal transplantation in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients in cyclosporin era. Am J Nephrol. 1997;17:440-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Xie Q, Li Y, Xue J, Xiong Z, Wang L, Sun Z, Ren Y, Zhu X, Hao CM. Renal phospholipase A2 receptor in hepatitis B virus-associated membranous nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:345-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Berchtold L, Zanetta G, Dahan K, Mihout F, Peltier J, Guerrot D, Brochériou I, Ronco P, Debiec H. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in hepatitis-B virus-associated PLA2R-positive membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;In Press. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fornairon S, Pol S, Legendre C, Carnot F, Mamzer-Bruneel MF, Brechot C, Kreis H. The long-term virologic and pathologic impact of renal transplantation on chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Transplantation. 1996;62:297-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hu TH, Tsai MC, Chien YS, Chen YT, Chen TC, Lin MT, Chang KC, Chiu KW. A novel experience of antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B in renal transplant recipients. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:745-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Harnett JD, Zeldis JB, Parfrey PS, Kennedy M, Sircar R, Steinmann TI, Guttmann RD. Hepatitis B disease in dialysis and transplant patients. Further epidemiologic and serologic studies. Transplantation. 1987;44:369-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fontaine H, Thiers V, Chrétien Y, Zylberberg H, Poupon RE, Bréchot C, Legendre C, Kreis H, Pol S. HBV genotypic resistance to lamivudine in kidney recipients and hemodialyzed patients. Transplantation. 2000;69:2090-2094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18665] [Cited by in RCA: 18038] [Article Influence: 1061.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14425] [Cited by in RCA: 17246] [Article Influence: 663.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | STROBE statement--checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies (STROBE initiative). Int J Public Health. 2008;53:3-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 13618] [Article Influence: 851.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 962] [Cited by in RCA: 1240] [Article Influence: 95.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 31208] [Article Influence: 780.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 48598] [Article Influence: 2113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 51. | Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2020] [Cited by in RCA: 2040] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ridruejo E, Brunet Mdel R, Cusumano A, Diaz C, Michel MD, Jost L, Jost L Jr, Mando OG, Vilches A. HBsAg as predictor of outcome in renal transplant patients. Medicina (B Aires). 2004;64:429-432. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Aroldi A, Lampertico P, Montagnino G, Passerini P, Villa M, Campise MR, Lunghi G, Tarantino A, Cesana BM, Messa P. Natural history of hepatitis B and C in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2005;79:1132-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Lee J, Cho JH, Lee JS, Ahn DW, Kim CD, Ahn C, Jung IM, Han DJ, Lim CS, Kim YS. Pretransplant Hepatitis B Viral Infection Increases Risk of Death After Kidney Transplantation: A Multicenter Cohort Study in Korea. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lee WC, Shu KH, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Chen CH, Lian JC. Long-term impact of hepatitis B, C virus infection on renal transplantation. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Breitenfeldt MK, Rasenack J, Berthold H, Olschewski M, Schroff J, Strey C, Grotz WH. Impact of hepatitis B and C on graft loss and mortality of patients after kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:130-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Morales JM, Domínguez-Gil B, Sanz-Guajardo D, Fernández J, Escuin F. The influence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in the recipient on late renal allograft failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19 Suppl 3:iii72-iii76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kanaan N, Raggi C, Goffin E, De Meyer M, Mourad M, Jadoul M, Beguin C, Kabamba B, Borbath I, Pirson Y. Outcome of hepatitis B and C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma occurring after renal transplantation. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kau A, Vermehren J, Sarrazin C. Treatment predictors of a sustained virologic response in hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:634-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lin KH, Chen YL, Lin PY, Hsieh CE, Ko CJ, Lin CC, Ming YZ. A Follow-Up Study on the Renal Protective Efficacy of Telbivudine for Hepatitis B Virus-Infected Taiwanese Patients After Living Donor Liver Transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2017;15:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Masutani K, Omoto K, Okumi M, Okabe Y, Shimizu T, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, Nakamura M, Ishida H, Tanabe K; Japan Academic Consortium of Kidney Transplantation (JACK) Investigators. Incidence of Hepatitis B Viral Reactivation After Kidney Transplantation With Low-Dose Rituximab Administration. Transplantation. 2018;102:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Lee J, Park JY, Huh KH, Kim BS, Kim MS, Kim SI, Ahn SH, Kim YS. Rituximab and hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/ anti-HBc-positive kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:722-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Battaglia Y, Cojocaru E, Forcellini S, Russo L, Russo D. Tenofovir and kidney transplantation: case report. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2016;4:18-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Miao B, Lao XM, Lin GL. Post-transplant withdrawal of lamivudine results in fatal hepatitis flares in kidney transplant recipients, under immune suppression, with inactive hepatitis B infection. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:1094-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hilmi I, Lu K S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF