Published online Nov 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i11.887

Peer-review started: June 4, 2018

First decision: July 10, 2018

Revised: August 15, 2018

Accepted: October 10, 2018

Article in press: October 10, 2018

Published online: November 27, 2018

Processing time: 176 Days and 20.4 Hours

Abdominal pain with elevated transaminases from inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction is a relatively common reason for referral and further workup by a hepatologist. The differential for the cause of IVC obstruction is extensive, and the most common etiologies include clotting disorders or recent trauma. In some situations the common etiologies have been ruled out, and the underlying process for the patient’s symptoms is still not explained. We present one unique case of abdominal pain and hepatomegaly secondary to IVC constriction from extrinsic compression of the diaphragm. Based on this patient’s presentation, we urge that physicians be cognizant of the IVC diameter and consider extrinsic compression as a contributor to the patient’s symptoms. If IVC compression from the diaphragm is confirmed, early referral to vascular surgery is strongly advised for further surgical intervention.

Core tip: Common etiologies of abdominal pain with elevated transaminases are clotting disorders and trauma. In this article, we present a rare case of external compression of the diaphragm as the cause of these symptoms that requires surgical intervention to relieve the obstruction.

- Citation: Grandhe S, Lee JA, Chandra A, Marsh C, Frenette CT. Trapped vessel of abdominal pain with hepatomegaly: A case report. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(11): 887-891

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i11/887.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i11.887

Inferior vena cava (IVC) obstruction presenting with abdominal pain and hepatomegaly is generally seen in patients with venous thromboses, including Budd Chiari syndrome, infective phlebitis, or in iatrogenic cases such as post-liver transplant or vascular catheter placement[1-4]. In the realm of obstetrics and gynecology, IVC obstruction is more commonly seen as vessel compression in the late second trimester of pregnancy[5]. Occasionally, tumors, such as renal cell carcinomas, may be initially detected due to compression of the IVC. Herein, we present a unique case of abdominal pain due to IVC constriction from extrinsic compression of the diaphragm. Previously this has been documented in patients with congenital chest wall abnormalities, such as pectus excavatum; however, this patient described below is one of the first to have this pathology without this birth defect[6].

A 49-year-old female was referred for further evaluation of hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, and thrombocytopenia. On interview, she endorsed a several year history of right upper quadrant abdominal pain and very mild dyspnea with exertion. She reported that the abdominal discomfort was worse in a sitting position. At the time of initial evaluation she was feeling well with no symptoms of jaundice, pruritus, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, edema, or ascites. She also reported no constitutional symptoms.

Past medical history was notable for a 10-year history of mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count 90000-130000) of unclear etiology with negative laboratory workup. Past surgical history was remarkable for an enlarged and nodular appearing liver observed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed one year prior due to the same symptoms. The patient has been followed by a hematologist as an outpatient, and a recent liver spleen single photon emission computed tomography scan had confirmed hepatomegaly without splenomegaly. Abdominal ultrasound characterized the liver as 18.1 cm in size with no evidence of cirrhosis or portal hypertension. Patent vasculature was reported throughout with normal hepatopedal flow. The patient had also previously undergone a computer tomography-guided liver biopsy, which showed mild perivascular and pericellular fibrosis but no evidence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly 4 cm below the costal margin but was otherwise unremarkable. Initial labs included a complete blood count (white count: 4.6, hemoglobin: 13.5, platelets: 112000), comprehensive metabolic panel (sodium: 141, potassium: 3.8, urea nitrogen: 11, creatinine: 0.8, alkaline phosphatase: 51, total protein: 7.3, aspartate aminotransferase: 30, and alanine aminotransferase: 29), and coagulation panel (international normalized ratio: 1.0). Additional workup revealed a ferritin of 28. Antimitochondrial antibody and actin IgG were negative. Ceruloplasmin level was 32. Patient also tested positive for antinuclear antibody titer (1:80, diffuse pattern) and epstein-barr virus IgG. An elevated transient elastography score of 9.6 was also noted.

Due to concern for early cirrhosis in the setting of thrombocytopenia and an elevated transient elastography score, the patient was advised to pursue a healthy lifestyle and abstain from alcohol. A magnetic resonance venography of the abdomen showed no evidence of thrombosis or obstruction.

At this point in time the patient reported worsening, intermittent, epigastric abdominal discomfort that radiated to the right upper quadrant of her abdomen, often waking her up at night and only improved with standing upright or walking. She occasionally felt nauseous but otherwise reported no jaundice, pruritus, edema, ascites, chest pain, or dyspnea. Physical examination showed a positive hepatojugular reflux, consistent with hepatic congestion. The patient was evaluated by a cardiologist, and a transthoracic echocardiogram showed pericardial thickening but no evidence of constrictive pericarditis or systolic or diastolic dysfunction.

The patient then underwent a transjugular liver biopsy with intravenous ultrasound and pressure measurements, which showed an elevated central venous pressure at 13-15 mmHg, wedged right hepatic vein pressure with occlusion balloon measuring 16-17 mmHg, and a dilated IVC of 3 cm cephalad to the patent veins prior to reentry into the right atrium. Significant respiratory variation involving near-collapse of the retrohepatic IVC at end-expiration was noted. There was question of intraluminal narrowing of the retrohepatic IVC down to approximately 10-15 mm, which had significantly improved upon Valsalva maneuver. Right heart catheterization showed hepatic congestion with normal intracardiac and pulmonary artery pressures.

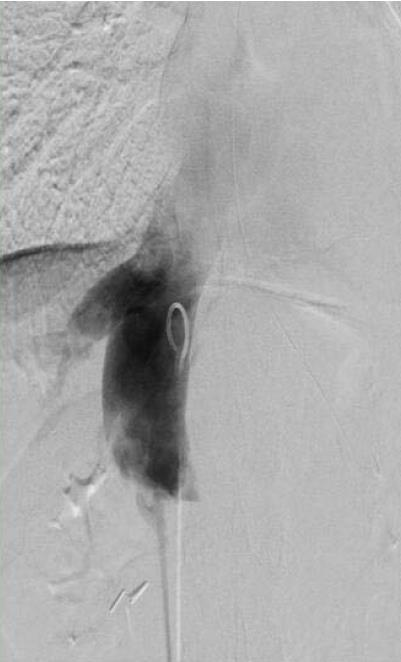

A multidisciplinary conference among the hepatology, vascular surgery, and cardiology services was held. It was suspected that the diaphragm, via the diaphragmatic hiatus through which the IVC was passing, was causing extrinsic compression of the vessel, thereby eliciting symptoms of epigastric and right upper quadrant pain. Repeat transient elastography was still elevated and the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy with IVC venolysis and division of the diaphragmatic constriction. After the above intervention, resolution of previously identified constriction was noted via repeat venogram (Figures 1 and 2) and intravascular ultrasound.

Intraoperative liver biopsy revealed sinusoidal congestion with dilatation in the perivenular areas, features consistent with extrahepatic venous outflow obstruction. The patient recovered remarkably well from the laparotomy. The available pre- and post-venolysis labs are presented in Table 1. At her four week postoperative follow up visit, she reported resolution of her abdominal discomfort and complete ability to perform her activities of daily living without the use of any pain medications. Unfortunately, follow-up liver enzymes were unable to be obtained due to losing her health insurance.

| Pre-venolysis | Post-venolysis | |

| Sodium | 137 | 137 |

| Potassium | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Chloride | 109 | 104 |

| Bicarbonate | 24 | 31 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 14 | 10 |

| Creatinine | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Glucose | 111 | 98 |

| Calcium | 7.4 | 8.3 |

| Alkaline phosphatase1 | 39 | --- |

| Albumin1 | 2.9 | --- |

| Total protein1 | 5.6 | --- |

| Aspartate aminotransferase1 | 49 | --- |

| Alanine aminotransferase1 | 43 | --- |

| Bilirubin, direct1 | 0.1 | --- |

| Bilirubin, total1 | 0.6 | --- |

The most common etiologies of IVC obstruction are from hypercoagulable states, inflammation, trauma, or recent surgery. Budd Chiari syndrome and hepatic vena cava syndrome, more common conditions associated with hepatic vein outflow obstruction, and hepatic vena cava syndrome may present subacutely or even arise from congenital strictures of the hepatic segment of the IVC[1,2]. While the cause of IVC obstruction is usually due to the abovementioned causes, it is important to consider extrinsic compression from neighboring tumors or even native structures, such as the diaphragm, as in the case outlined above. To date, very few cases have been published attributing abdominal pain or hepatomegaly to compression of the IVC by the diaphragm[7].

Chronic IVC obstruction may be silent in presentation or manifest late with acute symptoms of abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, renal dysfunction, or even unilateral limb symptoms such as leg heaviness, pain, swelling, or even cramping[8,9]. These unusual features may be anatomically related to the extensive network of collateralization of the natural and tributary vessels near the IVC.

The symptoms that arise from extrinsic compression and intrinsic occlusion of the IVC can be explained by understanding the embryological development of the large vessel. As the IVC develops near the liver and diaphragm, new outgrowths from hepatic veins and the infrarenal IVC may make this site more prone to developmental anomalies such as strictures and webs[8]. The patency of the iliac vein is important to collateral function, and occlusion of this vessel usually precipitates acute symptoms of abdominal pain[9]. However, the extent of collateralization may actually prevent patients from developing significant hepatic or renal dysfunction. In addition to the rich vasculature, studies analyzing the interaction between the diaphragm and the IVC during inspiration are limited, but they all support the idea that the size and shape of the lumen of the IVC can be altered by the contraction or anatomy of the diaphragm[7].

The diagnostic workup of IVC obstruction includes a color Doppler sonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or venography[9]. Intravascular ultrasound with pressure measurements and cavography provide an additional assessment of hepatic and collateral vein obstructions and thromboses and may indicate if these obstructions are subacute or chronic in nature[4]. Our patient showed evidence of IVC obstruction based on venography and intravascular ultrasound. In terms of therapeutic intervention, endovascular management of hepatic vein outflow obstruction usually includes portocaval shunts or balloon angioplasties with stent implantation[9,10]. Stent implantation via balloon angioplasty has proven to be safer with fewer complications of restenosis compared to open surgery[9].

IVC obstruction continues to remain an infrequent cause of abdominal pain and chronic liver disease. While this condition may be rare, it may lead to chronic abdominal pain, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension if not recognized and treated appropriately. Nonetheless, whether from intravascular obstruction, thrombosis, or extrinsic compression from neighboring structures, it is important to keep a broad differential and consider atypical causes of this phenomenon once common etiologies have been ruled out. Referral to vascular surgery may be necessary for surgical intervention, which will ultimately provide symptomatic relief for these patients.

Patients who present with abdominal pain and hepatomegaly are commonly diagnosed as having Budd Chiari or another type of obstruction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) whether it is intrinsic due to thrombosis or an obstruction. However, extrinsic compression, although rare, can also be the culprit of the patient’s symptoms.

Right upper quadrant and epigastric pain and hepatomegaly.

Budd Chiari, infective phlebitis, intravascular obstruction, thrombosis, or external compression from neighboring structures including the diaphragm, kidney, or uterus.

Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation panel, in addition to labs evaluating causes of cirrhosis including ferritin, anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, antinuclear antibody, and ceruloplasmin.

Color doppler sonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or venography.

Sinusoidal congestion with dilatation in the perivenular areas, features consistent with extrahepatic venous outflow obstruction.

Portocaval shunts or balloon angioplasties with stent implantation.

A case of IVC compression from the diaphragm has been reported only once in the literature from Louisiana State University Health Science Center in a patient with Pectus Excavatum. Interestingly an article from 1992 demonstrated how radiography can help identify how the IVC can be obstructed, but never specifically discussed a case in which the IVC was externally compressed by the diaphragm.

This case will guide clinicians to think of other etiologies that can cause abdominal pain and hepatomegaly in patients with unremarkable laboratory data. Biopsies are not necessary for this diagnosis. With consideration of this diagnosis, patient care will be expedited with quicker referrals, thereby minimizing the delay in treatment and resolution of symptoms.

| 1. | Schaffner F, Gadboys HL, Safran AP, Baron MG, Aufses AH Jr. Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by a web in the inferior vena cava. Am J Med. 1967;42:838-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shrestha SM, Kage M, Lee BB. Hepatic vena cava syndrome: New concept of pathogenesis. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:603-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shin N, Kim YH, Xu H, Shi HB, Zhang QQ, Colon Pons JP, Kim D, Xu Y, Wu FY, Han S. Redefining Budd-Chiari syndrome: A systematic review. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:691-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shrestha SM, Okuda K, Uchida T, Maharjan KG, Shrestha S, Joshi BL, Larsson S, Vaidya Y. Endemicity and clinical picture of liver disease due to obstruction of the hepatic portion of the inferior vena cava in Nepal. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:170-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ryo E, Okai T, Kozuma S, Kobayashi K, Kikuchi A, Taketani Y. Influence of compression of the inferior vena cava in the late second trimester on uterine and umbilical artery blood flow. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;55:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yalamanchili K, Summer W, Valentine V. Pectus excavatum with inspiratory inferior vena cava compression: a new presentation of pulsus paradoxus. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:45-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pearson AA, Sauter RW, Oler RC. Relationship of the diaphragm to the inferior vena cava in human embryos and fetuses. Thorax. 1971;26:348-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Raju S, Hollis K, Neglen P. Obstructive lesions of the inferior vena cava: clinical features and endovenous treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:820-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Srinivas BC, Dattatreya PV, Srinivasa KH, Prabhavathi , Manjunath CN. Inferior vena cava obstruction: long-term results of endovascular management. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kohli V, Pande GK, Dev V, Reddy KS, Kaul U, Nundy S. Management of hepatic venous outflow obstruction. Lancet. 1993;342:718-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

CARE Checklist (2013): The authors have read the CARE checklist and the manuscript was prepared and reviewed according to the CARE checklist.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Coelho JCU, Gencdal G, Kohla MAS, Roohvand F, Zhu Y S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW