Published online Jul 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1390

Revised: January 4, 2003

Accepted: February 11, 2003

Published online: July 15, 2003

AIM: To investigate the association of the NQO1 (C609T) polymorphism with susceptibility to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma (GCA) in North China.

METHODS: The NQO1 C609T genotypes were determined by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis in 317 cancer patients (193 ESCC and 124 GCA) and 165 unrelated healthy controls.

RESULTS: The NQO1 C609T C/C, C/T and T/T genotype frequency among healthy controls was 31.5%, 52.1% and 16.4% respectively. The NQO1 T/T genotype frequency among ESCC patients (25.9%) was significantly higher than that among healthy controls (χ2 = 4.79, P = 0.028). The NQO1 T/T genotype significantly increased the risk for developing ESCC compared with the combination of C/C and C/T genotypes, with an age, sex and smoking status adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.78 (1.04-2.98). This increased susceptibility was pronounced in ESCC patients with family histories of upper gastrointestinal cancers (UGIC) (adjusted OR = 2.20, 95%CI: 1.18-3.98). Similarly, the susceptibility of the NQO1 T/T genotype to GCA development was also observed among patients with family histories of UGIC, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.55 (95%CI: 1.21-5.23), whereas no difference in NQO1 genotype distribution was shown among patients without family histories of UGIC.

CONCLUSION: Determination of the NQO1 C609T genotype may be used as a stratification marker to predicate the individuals at high risk for developing ESCC and GCA in North China.

-

Citation: Zhang JH, Li Y, Wang R, Geddert H, Guo W, Wen DG, Chen ZF, Wei LZ, Kuang G, He M, Zhang LW, Wu ML, Wang SJ.

NQO1 C609T polymorphism associated with esophageal cancer and gastric cardiac carcinoma in North China. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(7): 1390-1393 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i7/1390.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1390

China is a country with high incidence regions of esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC) and gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma (GCA). Chemical carcinogenesis existed in consumed alcohol and tobacco or ingested food[1,2], nutrition deficiency[3], unhealthy living habits[2] and pathogenic infections[4-6] are in general considered as the risk factors for developing these two cancers. However, not all individuals exposed to the above exogenous risk factors will develop ESCC or GCA, indicating that the host susceptibility factors may play an important role in the cancer development. The role of a genetic background in developing these cancers was also strongly suggested by the familial clustering of upper gastrointestinal cancer (UGIC) patients in high incidence regions[7,8].

In recent years, many polymorphic genes encoded carcinogen metabolic enzymes have been found to be associated with susceptibility to chemically induced cancers such as esophageal cancer and gastric cancer[9-13]. NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) is a cytosolic enzyme which catalyzes the two-electron reduction of quinone compounds and prevents the generation of semiquinone free radicals and reactive oxygen species, thus protecting cells from oxydative damage[14]. On the other hand, NQO1 catalyzes the reductive activation of quinoid chemotherapeutic agents and of environmental carcinogens such as nitrosamines, heterocyclic amines and cigarette smoke condensate[15]. The activity of the NQO1 enzyme may be influenced by a single C to T substitution at nucleotide 609 of exon 6 of the NQO1 cDNA that causes the Pro187Ser amino acid change[16]. The homozygous wild-type (C/C) encodes NQO1 protein with complete enzyme activity, whereas the protein encoded by the heterozygous phenotype (C/T) has approximately three-fold decreased activity and the homozygous mutant (T/T) phenotype has a complete lack of enzyme activity[15-18]. The NQO1 C609T polymorphism is correlated with the susceptibility to several chemical carcinogen induced tumors such as lung cancer[19,20] and leukemia[21,22]. The association of NQO1 C609T polymorphism with the susceptibility to ESCC and GCA has not been reported so far. Therefore, the current study investigated the NQO1 C609T genotype distribution in ESCC and GCA patients and healthy controls from North China.

This case-control study recruited 317 patients with histologically confirmed cancers (193 esophageal cancer and 124 gastric cardiac cancer) and 165 unrelated healthy controls. The cancer patients were hospitalized for tumor resection in the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Hebei Medical University between 2001 and 2002. The histological pattern of the resected samples was determined by pathologists of the same hospital according to the international standard[23]. The healthy controls were unrelated blood donors or voluntary staff of Hebei Cancer Institute. All of the patients and controls were from Shijiazhuang city or its surrounding regions. The information about sex, age, smoking habits and family history was obtained from the cancer patients by their hospital recordings and from the healthy controls by interview directly after bleeding. The smokers were defined as ex- or current smoking 5 cigarettes per day for at least two years. The individuals with at least one first-degree relative or at least two second-degree relatives having esophageal/cardiac/gastric cancer were defined as having family histories of upper gastrointestinal cancers (UGIC). The informed consent was obtained from all the recruited subjects. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hebei Cancer Institute. The demographic data of the cancer patients and healthy controls are presented in Table 1.

| Groups | Control n (%) | ESCC n (%) | GCA n (%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 109 (66.1) | 124 (64.3) | 92 (74.2) |

| Female | 56 (33.9) | 69 (35.7) | 32 (25.8) |

| Mean age ± SD (yrs) | 52 ± 7.16 | 59 ± 8.73 | 60 ± 8.24 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 82 (49.7) | 104 (53.9) | 68 (59.8) |

| Non-smoker | 83 (50.3) | 89 (46.1) | 46 (40.2) |

| Family history of UGIC | |||

| Positive | 0 | 86 (44.6) | 45 (36.3) |

| Negative | 165 (100) | 107 (55.4) | 79 (63.7) |

| Genotype | |||

| C/C | 52 (31.5) | 51 (26.4) | 40 (32.3) |

| C/T | 86 (52.1) | 92 (47.7) | 55 (44.3) |

| T/T | 27 (16.4) | 50 (25.9)a | 29 (23.4) |

| Allele type | |||

| C | 190 (57.6) | 194 (50.3) | 135 (54.4) |

| T | 140 (42.4) | 192 (49.7)b | 113 (45.6) |

Five mL of venous blood from each subject was drawn in vacutainer tubes containing EDTA. The genomic DNA was extracted within one week after bleeding using proteinase K digestion followed by a salting out procedure.

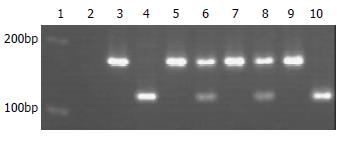

NQO1 genotyping of healthy controls and ESCC patients was performed at the Molecular Laboratory of the Institute of Pathology, Heinrich-Heine University, Duesseldorf. The genotyping of the GCA patients was performed at the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Hebei Cancer Institute with the same reagents and the same methods. The base change (C to T) at nucleotide 609 of NQO1 cDNA created a Hinf I restriction site. Therefore, the NQO1 C609T genotyping was performed by PCR and subsequent restriction fragment analysis. PCR was performed in a 25 μL volume containing 100 ng DNA template, 2.5 μL 10 × PCR-buffer, 1 U Hotstar Taq-DNA-polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 200 μmol dNTPs and 10 pmol sense primer (5'-AAGCCCAGACCAACTTCT-3') and antisense primer (5'-ATTTGAATTCGGGCGTCTGCTG-3'). Initial denaturation for 14 min at 94 °C was followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, at 56 °C for 1 min, and at 72 °C for 2 min. The PCR products were subsequently digested with 20 units of Hinf I (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) for 3 h at 37 °C and separated on a 2% agarose gel (Figure 1). The NQO1 wild-type allele showed a 172-bp PCR product resistant to enzyme digestion, whereas the null allele showed a 131-bp and a 41-bp band. For quality control, each PCR reaction used distilled water instead of DNA as a negative control, and 10% of the samples were analyzed twice.

The comparison of NQO1 genotype distribution in the study groups was performed by means of two-sided contingency tables using χ2 test. Hardy-Weinberg analysis was performed to compare the observed and expected genotype frequencies using χ2 test. A probability level of 5% was made as statistically significant. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and adjusted for age, sex and smoking status with the unconditional logistic regression model. Statistical analysis was made using SPSS software package (10.0 version).

As shown in Table 1, the composition of gender, age and the proportion of smokers in ESCC and GCA patients were compared with the healthy controls. Eighty-six (44.6%) of the ESCC and 45 (36.3%) of the GCA patients had family histories of UGIC. The proportion of age, sex and smoking status in ESCC and GCA patients with and without family histories of UGIC was also not significantly different (data not shown). None of the healthy controls had a family history of UGIC.

The NQO1 C609T genotyping was successfully performed in all study subjects. The observed NQO1 genotype frequencies were not significantly deviated from those expected from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the healthy controls (χ2 = 0.061;P = 0.970), ESCC patients (χ2 = 0.166; P = 0.920) and GCA patients (χ2 = 0.832; P = 0.660). The NQO1 C609T genotype distribution among healthy controls was 31.5% (C/C), 52.1% (C/T), and 16.4% (T/T) respectively (Table 1). The genotype distribution was not correlated with gender, age and smoking status in each study group (data not shown).

The overall NQO1 null-allele frequency among ESCC patients (49.7%) was marginally higher than that among healthy controls (42.4%) (χ2 = 3.83, P = 0.05). There was no difference in allele distribution between GCA patients and healthy controls (χ2 = 0.567, P = 0.451) (Table 1). The distribution of NQO1 C/C and C/T genotypes among ESCC and GCA patients was not significantly different from that among healthy controls (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Interestingly, in ESCC patients, the NQO1 T/T genotype was significantly more frequent (25.9%) than that among healthy controls (χ2 = 4.79, P = 0.028) (Table 2). The relative risk of the T/T genotype for the ESCC development was increased by about 1.8 fold compared with the combination of the C/C or C/T genotypes, with an age, sex and smoking status adjusted odds ratio of 1.78 (95%CI: 1.04-2.98). When stratified for the family history of UGIC, the NQO1 T/T genotype was significantly more common among patients with family histories of UGIC (30.2%) than that among healthy controls (χ2 = 6.53, P = 0.011). The T/T genotype significantly increased the risk for developing ESCC among patients with family histories of UGIC, compared with the C/C and C/T genotypes (adjusted OR = 2.20, 95%CI: 1.18-3.98). In contrast, the NQO1 T/T genotype frequency was not significantly different between ESCC patients without family history of UGIC (22.4%) and healthy controls (χ2 = 1.49, P = 0.223) (Table 2).

| Groups | NQO1 genotype | aOR (95%CI)d | |

| C/C+C/T n (%) | T/T n (%) | ||

| Healthy controls | 138 (83.6) | 27 (16.4) | |

| ESCC patient | 143 (74.1) | 50 (25.9)a | 1.78 (1.04-2.98) |

| Family history of UGIC | |||

| Positive | 60 (69.8) | 26 (30.2)b | 2.20 (1.18-3.98) |

| Negative | 83 (77.6) | 24 (22.4) | 1.46 (0.79-2.63) |

| GCA patient | 95 (76.6) | 29 (23.4) | 1.44 (0.86-2.30) |

| Family history of UGIC | |||

| Positive | 30 (66.7) | 15 (33.3)c | 2.55 (1.21-5.23) |

| Negative | 65 (82.3) | 14 (17.7) | 1.10 (0.80-1.34) |

In line with the result of ESCC, the NQO1 T/T genotype significantly increased the risk for developing GCA compared with the C/C and C/T genotypes. However, this increased risk was only demonstrated when stratified for the family history. Thus, among GCA patients with family histories of UGIC, the T/T frequency (33.3%) was significantly higher than that among healthy controls (χ2 = 6.36, P = 0.012). In this patient group, the relative risk of the T/T genotype for developing GCA was more than two-fold higher compared with the combination of C/C and C/T genotypes (adjusted OR = 2.55, 95%CI: 1.21-5.23), whereas the NQO1 T/T genotype frequency among the overall GCA patients (23.4%) and GCA patients without family histories of UGIC (17.7%) remained similar to that of the healthy controls (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

To observe the different influence of the NQO1 C609T polymorphism on the ESCC or GCA development among smokers and non-smokers, the genotype distribution was also stratified according to the smoking habits. No difference in NQO1 genotype distribution among smoking or non-smoking ESCC and GCA patients was observed as compared with that of the healthy controls (data not shown).

Both of ESCC and GCA are characterized by a particularly poor prognosis since most of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages. Endoscopic examination is the only feasible way to detect ESCC and GCA at early and/or precancerous stages. However, the wide application of this method is limited by the high cost and painfulness of the examination. The laboratory identification of high-risk individuals, in combination with the clinical detection, will provide a promising way to detect the early tumors.

The present hospital based case control study suggests that NQO1 C609T homozygous null genotype may increase the susceptibility to ESCC and GCA in the northern Chinese population. This result is consistent with the previous investigations, which showed that the NQO1 homozygous null genotype increased the susceptibility to other tumor types such as lung cancer[19], leukemia[21,22] and cutaneous cancers[24]. The underlying mechanism of the correlation of NQO1 C609T polymorphism with increased risk for developing various tumors may be related to the different enzyme activities encoded by the different NQO1 genotypes. Thus, lack of NQO1 activity encoded by the homozygous null genotype results in a reduced detoxification of exogenous carcinogens and leads cells to be easily damaged by oxidation, and thereby increasing the susceptibility to chemically induced cancers such as ESCC and GCA. In addition, the recessive effect of the NQO1 C609T null allele on the development of ESCC and GCA was suggested by the current study, since the heterozygous genotype frequency among tumor patients was similar to that among healthy controls. The result indicates that although the NQO1 heterozygous genotype results in a three-fold decrease of the NQO1 enzyme activity, it may be sufficient for protecting cells from damage by exogenous carcinogens.

In this study, the increased risk of the NQO1 C609T homozygous null genotype for developing both of ESCC and GCA was only evident in patients with family histories of UGIC, indicating that in families aggregated with UGIC patients, a predisposition to ESCC and GCA may be inherited by lack of NQO1 enzyme activity. A strong association of increased risk for esophageal cancer with a positive family history of UGIC in the first-degree relatives has been reported in the high incidence regions of China[7,8]. The segregation analysis on the high-risk nuclear families suggested that the ESCC occurrence was best fit to the autosomal recessive Mendelian inheritance[8]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms for the familial clustering of UGIC patients have not been elucidated so far. Our results suggested, that the NQO1 C609T polymorphic gene, together with other possible susceptible genes, might give an opportunity to challenge the genetic mechanisms of cancer development in the UGIC clustered families and provide a chance to predict high-risk individuals in the high-incidence regions. In addition, the consistent association of NQO1 C609T polymorphism with the susceptibility to ESCC and GCA, as shown in this study, supports that there might be a common genetic background in the development of these two tumor types. However, the result should be interpreted cautiously, since the number of cases, especially in the subgroup analyses, was probably too small to draw a final conclusion.

In summary, our preliminary data suggest that the NQO1 C609T gene polymorphism may influence the susceptibility to ESCC and CAC in a northern Chinese population. Determination of NQO1 C609T genotype may provide a useful genetic marker in predicating high-risk individuals for the development of ESCC and CAC. It is worthwhile conducting additional population-based studies including enlarged subjects before its clinical application.

We greatly acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Mrs. C. Pawlik, Mrs. H. Huss and Mrs. B. Maruhn-Debowski. We also thank Mrs. Heyu Tong, Mr. Fanshu Meng, and Mr. Baoshan Zhao for their assistance in recruiting study subjects.

| 1. | Launoy G, Milan CH, Faivre J, Pienkowski P, Milan CI, Gignoux M. Alcohol, tobacco and oesophageal cancer: effects of the duration of consumption, mean intake and current and former consumption. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1389-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yokokawa Y, Ohta S, Hou J, Zhang XL, Li SS, Ping YM, Nakajima T. Ecological study on the risks of esophageal cancer in Ci-Xian, China: the importance of nutritional status and the use of well water. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:620-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cai L, Yu SZ, Zhang ZF. Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of gastric cancer in Changle County, Fujian Province, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:374-376. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Matsha T, Erasmus R, Kafuko AB, Mugwanya D, Stepien A, Parker MI. Human papillomavirus associated with oesophageal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:587-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lavergne D, de Villiers EM. Papillomavirus in esophageal papillomas and carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:681-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chang-Claude J, Becher H, Blettner M, Qiu S, Yang G, Wahrendorf J. Familial aggregation of oesophageal cancer in a high incidence area in China. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1159-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang W, Bailey-Wilson JE, Li W, Wang X, Zhang C, Mao X, Liu Z, Zhou C, Wu M. Segregation analysis of esophageal cancer in a moderately high-incidence area of northern China. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matsuo K, Hamajima N, Shinoda M, Hatooka S, Inoue M, Takezaki T, Tajima K. Gene-environment interaction between an aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) polymorphism and alcohol consumption for the risk of esophageal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:913-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Song C, Xing D, Tan W, Wei Q, Lin D. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms increase risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3272-3275. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tan W, Song N, Wang GQ, Liu Q, Tang HJ, Kadlubar FF, Lin DX. Impact of genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 2E1 and glutathione S-transferases M1, T1, and P1 on susceptibility to esophageal cancer among high-risk individuals in China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:551-556. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Cai L, Yu SZ, Zhang ZF. Glutathione S-transferases M1, T1 genotypes and the risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:506-509. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cai L, Yu SZ, Zhan ZF. Cytochrome P450 2E1 genetic polymorphism and gastric cancer in Changle, Fujian Province. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:792-795. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Winski SL, Koutalos Y, Bentley DL, Ross D. Subcellular localization of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1420-1424. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Larson RA, Wang Y, Banerjee M, Wiemels J, Hartford C, Le Beau MM, Smith MT. Prevalence of the inactivating 609C--& gt; T polymorphism in the NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) gene in patients with primary and therapy-related myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:803-807. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kuehl BL, Paterson JW, Peacock JW, Paterson MC, Rauth AM. Presence of a heterozygous substitution and its relationship to DT-diaphorase activity. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moran JL, Siegel D, Ross D. A potential mechanism underlying the increased susceptibility of individuals with a polymorphism in NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) to benzene toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8150-8155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smith MT. Benzene, NQO1, and genetic susceptibility to cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7624-7626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen H, Lum A, Seifried A, Wilkens LR, Le Marchand L. Association of the NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 609C--& gt; T polymorphism with a decreased lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3045-3048. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Xu LL, Wain JC, Miller DP, Thurston SW, Su L, Lynch TJ, Christiani DC. The NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene polymorphism and lung cancer: differential susceptibility based on smoking behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:303-309. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Wiemels JL, Pagnamenta A, Taylor GM, Eden OB, Alexander FE, Greaves MF. A lack of a functional NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase allele is selectively associated with pediatric leukemias that have MLL fusions. United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4095-4099. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Smith MT, Wang Y, Kane E, Rollinson S, Wiemels JL, Roman E, Roddam P, Cartwright R, Morgan G. Low NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 activity is associated with increased risk of acute leukemia in adults. Blood. 2001;97:1422-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gabbert HE, Shimoda T, Hainaut P, Nakamura Y, Field JK, Inoue H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Lyon IARCP Press. 2000;11-32. |

| 24. | Clairmont A, Sies H, Ramachandran S, Lear JT, Smith AG, Bowers B, Jones PW, Fryer AA, Strange RC. Association of NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) null with numbers of basal cell carcinomas: use of a multivariate model to rank the relative importance of this polymorphism and those at other relevant loci. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1235-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Edited by Ma JY