Published online Dec 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2805

Revised: September 13, 2003

Accepted: October 12, 2003

Published online: December 15, 2003

AIM: Bleeding and perforation are major and serious complications associated with endoscopic polypectomy. To develop a safe and effective method to resect hyperplastic polyps of the stomach, we employed rubber bands to strangulate hyperplastic polyps and to determine the possibility of inducing avascular necrosis in these lesions.

METHODS: Forty-seven patients with 72 hyperplastic polyps were treated with endoscopic banding ligation (EBL). At 14 days after endoscopic ligation, follow-up endoscopies were performed to assess the outcomes of the strangulated polyps.

RESULTS: After being strangulated by the rubber bands, all of the polyps immediately became congested (100%), and then developed cyanotic changes (100%) approximately 4 minutes later. On follow-up endoscopy 2 weeks later, all the polyps except one had dropped off. The only one residual polyp shrank with a rubber band in its base, and it also dropped off spontaneously during subsequent follow-up. No complications occurred during or following the ligation procedures.

CONCLUSION: Gastric polyps develop avascular necrosis following ligation by rubber bands. Employing suction equipment, EBL can easily capture sessile polyps. It is an easy, safe and effective method to eradicate hyperplastic polyps of the stomach.

- Citation: Lo CC, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Tseng HH, Chen HC, Hsu PN, Lin CK, Chan HH, Tsai WL, Chen WC, Wang EM, Lai KH. Endoscopic banding ligation can effectively resect hyperplastic polyps of the stomach. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(12): 2805-2808

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i12/2805.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2805

Bleeding is the most common complication of electrocautery snare polypectomy for upper gastrointestinal polyps, with an incidence ranging from 6.0% to 7.2% in prospective studies[1-3]. To prevent polypectomy-elicited bleeding, epinephrine injection into the stalk[2] or placement of a metallic clip[4,5] before resection has been employed. Hachisu et al[6] also reported favorable results of preventive ligation during polypectomy with placement of detachable snares at the bases of polyps. However, it is difficult to place detachable snares on sessile polyps or on polyps situated in technically difficult areas.

Endoscopic ligation using suction equipment and rubber bands or detachable snare[7-12] have been extensively applied in the management of bleeding esophageal and gastric varices. The varices are automatically eradicated through the use of ligation. In our pilot studies[13,14], we used detachable snares to strangulate gastric polyps, and demonstrated that most gastric polyps (89%) developed avascular necrosis following ligation. Those results implied that a strangulating technique alone can achieve the bloodless transection of gastrointestinal neoplasm. However, it is important to note that a significant portion of gastric polyps (11%) remain alive following detachable snare ligation. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of endoscopic banding ligation (EBL) for removal of hyperplastic polyps of the stomach.

From June 2000 to October 2001, forty-five patients (30 men and 15 women) who had 70 hyperplastic polyps documented in previous endoscopic biopsies were electively treated with EBL. Another two male patients received emergent EBL to treat bleeding gastric polyps. The mean patient age was 59.9 years (range 14 to 75 years). Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects. The characteristics of their polyps are analyzed and illustrated in Table 1. The mean diameter of the head of polyps was 9.3 mm (range 5 to 25 mm).

| Variables | Number |

| Number of cases (M/F) | 47 (32/15) |

| Age ( years ± SD) | 59.9 ± 15.1 |

| Number of polyps | 72 |

| Mean size of polyps | 9.3 mm (5-25 mm) |

| Morphology of polyps | |

| Sessile | 70 (97.2%) |

| Pedunculated | 2 (2.8%) |

| Location of polyps | |

| Cardia (superior, inferior, anterior, posterior) | (0, 1, 0, 2) |

| Fundus (superior, inferior, anterior, posterior) | (1, 4, 4, 1) |

| Antrum (superior, inferior, anterior, posterior) | (4, 5, 9, 7) |

| Body (superior, inferior, anterior, posterior) | (5, 10, 4, 15) |

| Initial endoscopic findings after ligation | |

| Congestion | 72 (100%) |

| Cyanosis | 72(100%) |

| Endoscopic findings at second look | |

| Shrunken polyps | 1 (1.4%)a |

| Ligation-related ulcer | 71 (98.6%) |

EBL was carried out with a GIF XQ200 endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and a 19 cm flexible overtube (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan). We set a transparent hood at the end of a scope that was equipped with a pneumoactivated esophageal variceal ligation (EVL) device set (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan). The EVL device set consisted of an air feeding tube, a sliding tube, an inner cylinder, and a rubber band (O-ring). Pumping through an air feeding tube made a sliding tube slide on an inner cylinder and, as a result, the rubber band slipped off, thus ligating a lesion aspirated into the hood.

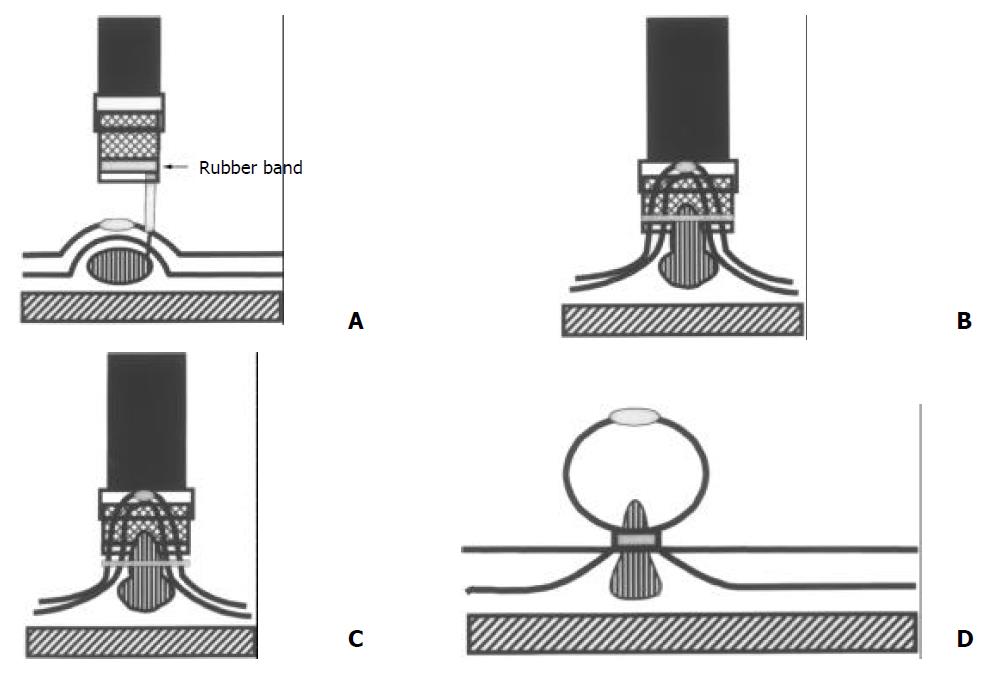

As premedication, 20 mg of hyoscine-N-butylbromide was given intramuscularly 5 minutes before performing EBL. The endoscope with a flexible overtube attached to its base was inserted and the overtube was inserted gently over the endoscope to avoid mechanical injury to the thorax, larynx, and cervical esophagus. Before banding ligation, one to 4 ml of distilled water was injected into the submucosal layer near the lesion to tear and lift it off the muscle layer (Figure 1A). The endoscope was removed, and the pneumoactivated EVL device set was assembled on the instrument, which was then reinserted through the overtube. The raised lesion was aspirated into the hood (Figure 1B) and ligated with the rubber band after air was pumped through the air feeding tube (Figure 1C). Also, the polyp was observed for 5 minutes to investigate the sequential macroscopic changes of the strangulated lesion after EBL and biopsies were conducted later.

After the procedure, the patient was allowed to consume a liquid meal for a 24 hour period, and then issued a regular diet. An H2-receptor antagonist was administered orally for 4 weeks. A follow-up endoscopy was performed 14 days after initial endoscopic ligation to assess the outcome of the strangulated polyp.

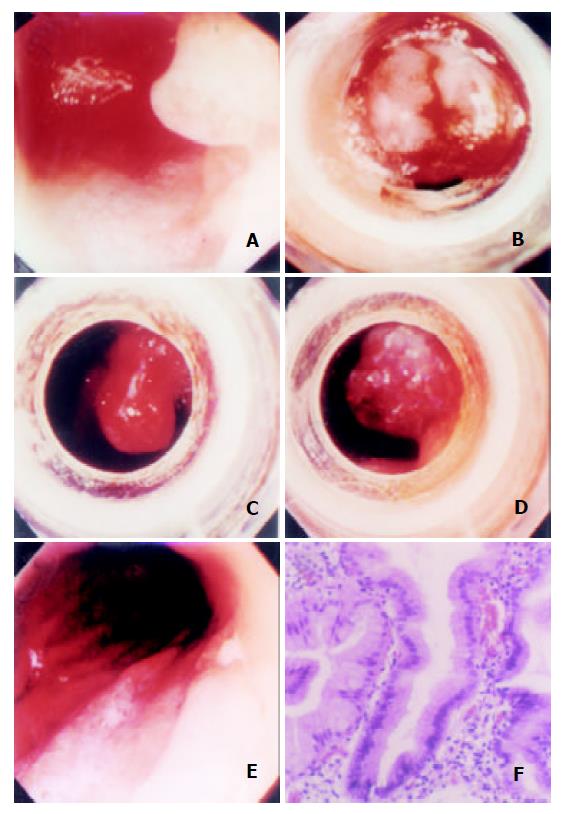

Table 1 summarizes the results of 47 patients treated with EBL. EBL was performed easily and safely in each case. Following strangulation with detachable snares, all of the polyps immediately became congested (100%), and then developed cyanotic change (100%) approximately 4 minutes later. Figure 2 displays the typical sequential changes of a strangulated polyp. Following ligation, biopsies were conducted, and almost no bleeding was induced by biopsy procedures from the strangulated polyps. Pathological examination revealed severe venous congestion in the lamina propria of the lesions (Figure 2F). In the case of the two patients with bleeding gastric polyps above the antrum, EBL achieved successful hemostasis. The biopsies of polyps following EBL disclosed that they were hyperplastic lesions.

The follow-up endoscopy 2 weeks later revealed that all the polyps except one had dropped off, and EBL-related ulcers were found at the sites of the original lesions. The only one residual polyp shrank with a rubber band at its base. An additional follow-up endoscopy was performed for this lesion 1 month later, revealing that both the ligated polyp and rubber band had disappeared. No complications, such as bleeding or perforation, occurred during or after EBL and biopsies.

The current study has confirmed that gastric hyperplastic polyps developED avascular necrosis following EBL. A strangulated polyp became congested immediately after ligation, and developed cyanotic changes within a few minutes. These important findings herein have not been documented before. Our study also reveals that EBL can be applied not only in the elective treatment of asymptomatic hyperplastic polyps, but also in the management of bleeding lesions. A strangulated polyp was bloodlessly transected without complications following the banding ligation.

Hyperplastic polyp is the most common polyp in the stomach, comprising 75% to 90% of gastric polyps[15-17]. Most of the hyperplastic gastric polyps are asymptomatic. However, malignant transformation of hyperplastic polyps has been reported in several long-term follow-up studies[18,19]. They therefore should be resected when incidentally detected. Bleeding is a common complication of electrocautery snare polypectomy for gastric polyps. In a well-conducted prospective study[2], bleeding was observed in 16 of 222 snare polypectomies (7.2%). Recently, various endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) techniques have been developed. They included strip biopsy[20], double snare polypectomy[21] and cap-fitted panendoscopy[22]. However, complications (bleeding and perforation) of these new techniques were also high with an incidence ranging from 2.7% to 23.9%[23-25]. These studies underscored the importance of proficiency in endoscopic hemostatic techniques by the endoscopic team as a prerequisite for performing polypectomy in the stomach.

To prevent hemorrhage following polypectomy, preventive ligation could be conducted before the procedure[6]. However, bleeding can be encountered if a polyp is resected by electrocautery in cases where the distance above the detachable snare or rubber band is inadequate. According to our results, single ligation could effectively remove all the gastric polyps without requiring further electrocautery. No complications occurred during or after ligation. The low bleeding rate associated with EBL seemed to be attributed mainly to both a ligation of the vessels at the polyp bases and the avoidance of resecting polyps with a high-frequency electrocautery. Additionally, perforation was prevented by lifting the lesion from the muscle layer.

Our results further demonstrated that the ligating method could be employed to treat actively bleeding polyps. In the two patients with bleeding gastric polyps, EBL successfully achieved hemostasis for their bleeding polyps. Furthermore, the strangulated polyps were bloodlessly transected without complications following the banding.

Conventional snare polypectomy or EMR methods encounter difficulties in effectively managing lesions located in the lesser curvature side, posterior wall and cardia of the stomach. Employing the EBL method allowed a lesion to be easily captured into the transparent hood, even in cases where it was situated tangentially.

Sessile polyps pose another dilemma for traditional electrocautery polypectomy, and it is difficult for snare to capture these polyps. EMR with cap-fitted panendoscopy[22] may solve this problem, but bleeding and perforation remain very problematic. Employing the proposed EBL procedure allowed theses polyps to be easily captured after submucosal injection with distilled water followed by suction. However, our EBL technique is not suitable for treating gastric adenoma, which has a high risk of carcinomatous conversion[16,17]. In managing such lesions, additional electrocautery is still required to assess the possibility of malignant transformation of polyps.

Previously, we also employed the endoscopic detachable snare ligation method to treat hyperplastic gastric polyps[13], and found that cyanotic change was an important predictor of the outcome of strangulated polyps. All the polyps with cyanotic changes developed avascular necrosis, but those without cyanotic changes remained alive following ligation by detachable snares. This study demonstrated that all the polyps became cyanotic following ligation by rubber bands, and that all the cyanotic polyps then developed avascular necrosis.

In conclusion, gastric polyps congest immediately following strangulation by rubber bands, and then develop cyanotic change within a few minutes. Avascular necrosis occurs in all the gastric polyps following banding ligation. Employing suction equipment, EBL can easily capture sessile polyps. It is an easy, safe and effective method to eradicate gastric hyperplastic polyps. Additionally, the new technique may be the choice of therapy for bleeding gastrointestinal polyps.

The authors would like to express their deep appreciation to Dr. Chang-Bih Shie, Jeng-Jie Pzeng, Miss Yu-San Chen, and Hsuan-Chun Huang for their invaluable support to this study.

| 1. | Lanza FL, Graham DY, Nelson RS, Godines R, McKechnie JC. Endoscopic upper gastrointestinal polypectomy. Report of 73 polypectomies in 63 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;75:345-348. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Muehldorfer SM, Stolte M, Martus P, Hahn EG, Ell C. Diagnostic accuracy of forceps biopsy versus polypectomy for gastric polyps: a prospective multicentre study. Gut. 2002;50:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hsieh YH, Lin HJ, Tseng GY, Perng CL, Li AF, Chang FY, Lee SD. Is submucosal epinephrine injection necessary before polypectomy A prospective, comparative study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1379-1382. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Chang FY. Endoscopic ligation for removal of stomach hyperptastic polyp: less risk or saving money. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi (Taipei). 2001;64:615-616. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sobrino-Faya M, Martínez S, Gómez Balado M, Lorenzo A, Iglesias-García J, Iglesias-Canle J, Domínquez Muñoz JE. Clips for the prevention and treatment of postpolypectomy bleeding (hemoclips in polypectomy). Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2002;94:457-462. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hachisu T. A new detachable snare for hemostasis in the removal of large polyps or other elevated lesions. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Prisco A, Garofano ML. Emergency endoscopic ligation of actively bleeding gastric varices with a detachable snare. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:400-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Huang HC, Hsu PI, Lin CK. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:461-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Hsu PI, Chiang HT. Prophylactic banding ligation of high-risk esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: a prospective, randomized trial. J Hepatol. 1999;31:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lo GH, Chen WC, Chen MH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Tsai WL, Lai KH. Banding ligation versus nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:728-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Hou MC, Chen WC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A new "sandwich" method of combined endoscopic variceal ligation and sclerotherapy versus ligation alone in the treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:572-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deschênes M, Barkun AN. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:630-633. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lo GH, Lin CK, Lo CC, Wang EM, Wang YY, Tsai WL, Lin CP, Tseng HH. Sequential changes of gastric hyperplastic polyps following endoscopic ligation. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi (Taipei). 2001;64:609-614. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lo GH, Lin CK, Lo CC, Wang EM, Wang YY, Tsai WL, Lin CP, Tseng HH. Sequential changes of gastric hyperplastic polyps following endoscopic ligation. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi (Taipei). 2001;64:609-614. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Koch HK, Lesch R, Cremer M, Oehlert W. Polyps and polypoid foveolar hyperplasia in gastric biopsy specimens and their precancerous prevalence. Front Gastrointest Res. 1979;4:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Laxén F, Sipponen P, Ihamäki T, Hakkiluoto A, Dortscheva Z. Gastric polyps; their morphological and endoscopical characteristics and relation to gastric carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A. 1982;90:221-228. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rösch W. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of benign gastric tumours. Front Gastrointest Res. 1980;6:167-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Daibo M, Itabashi M, Hirota T. Malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1016-1025. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kamiya T, Morishita T, Asakura H, Munakata Y, Miura S, Tsuchiya M. Histoclinical long-standing follow-up study of hyperplastic polyps of the stomach. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;75:275-281. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Karita M, Tada M, Okita K. The successive strip biopsy partial resection technique for large early gastric and colon cancers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:174-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Takekoshi T, Takagi K, Kato Y. Radical endoscopic treatment of early gastric cancer. Gann Monogr Cancer Res. 1990;37:111-126. |

| 22. | Inoue H, Takeshita K, Hori H, Muraoka Y, Yoneshima H, Endo M. Endoscopic mucosal resection with a cap-fitted panendoscope for esophagus, stomach, and colon mucosal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hirao M, Asanuma T, Masuda K. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer following locally injecting hypertonic saline-epinephrine. Stomach Intest. 1988;23:399-409. |

| 24. | Yokota K, Tanabe Y, Komatsu H. Safety and risk in the endo-scopic mucosal resection of gastric disease: the strip biopsy method. Endoscopia Digestiva. 1996;8:465-471. |

| 25. | Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Long WB, Furth EE, Ginsberg GG. Efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection: a study of 101 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:390-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Edited by Zhu LH