INTRODUCTION

Stress has been shown to induce gastric mucosal lesions and lower the effectiveness of the mucosa as a barrier[1-6]. In rats, gastric ulcers can be produced by cold-restraint stress[7-9] and it is frequently employed as a model for the study of the mechanisms of stress on ulcer formation. Cold-restraint stress, however, is not normally encountered in human subjects while sleep deprivation is a common experience among city dwellers. swift workers and medical professionals. It imposes stress on the body, and produces a variety of health problems[10-14]. Sleep deprivation is associated with poor congitive ability, and shortening of longevity[15]. Studies have found that the cognitive function of doctors after a night shift was considerably decreased. Sleep deprivation is also a major problem in the intensive care units and it has been suggested to affect the healing process of patients thus contributing to an increase in morbidity and mortality[16]. Sleep deprivation has been shown to induce typical dermatitis in experimental animals. Severe ulcerative and hyperkeratotic skin lesions localized to the paws and tails developed in rats deprived of sleep[17]. This effect of sleep deprivation may affect the epithelial linings of the gastrointestinal tract, because stress has been demonstrated to produce gastric mucosal lesions in rats[18,19]. Our previous works showed that the food and water consumption in sleep disturbed rats were not affected but they had a smaller percentage gain in body weight. The locomotion activities of sleep disturbed rats were similar to the controls, however, their adrenal weights were increased[20]. The mucosal epithelial cell proliferation rate was also suppressed by sleep disturbance. Although various factors have been proposed to account for this process, the precise mechanism of how sleep deprivation affects the gastric mucosa barrier, especially at the molecular level, still remains unclear. Previously, we used cDNA expression arrays to identify genes that abnormal expressed in gastric mucosa of sleep deprivation rats[20]. In this project, inducible heat shock protein 70, one candidate gene emerging from cDNA array for its potential significance was further analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rats and reagents

Male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 180 g-200 g were used in the experiments. They were housed in a temperature 22 °C ± 1 °C and humidity 65%-70% controlled room with a day night cycle of 12 h. The rats were given standard laboratory diet (Ralston Purina Co., Chicago, IL) and tap water ad libitum. Rats were starved for 24 h and water withdrawn 1 hour prior to any oral or intragastric administration of agents in order to obtain a uniform distribution of those agents onto the gastric mucosa. All chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, USA) unless specified otherwise. The present study has been examined and approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Rats for Teaching and Research of the University of Hong Kong.

Sleep disturbance

Rats for sleep disruption were placed inside a computerized rotating drum while the control animals were left undisturbed in a stationary drum. The drum was rotated 180o in 30 s at 5 minutes intervals and was programed to switch off for 1 h every day at 13:00 to allow for an hour of undisturbed sleep. Sleep disturbance was continued for 1 wk before the animals were killed.

Collection of gastric mucosa

Rats were killed by ether anesthesia followed by cutting off the abdominal aortic artery. The stomachs were removed rapidly, opened along the greater curvature, and rinsed with cooled normal saline thoroughly. A longitudinal section of gastric tissue was taken from the anterior part of the stomach and then fixed in 100 mL·L-1 buffered formalin for 24 h. It was cut into sections of 5 µm and then used in immunostaining. Gastric mucosa was taken from the remaining part of the stomach by scraping with a glass slide on a glass dish on ice. They were wrapped by a piece of aluminum foil, immediately froze in liquid nitrogen and stored at -70 °C until assayed.

Detection of inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA expression by RT-PCR[

21-23]

Total RNA was extracted from gastric mucosa of rats by using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Gaitherburg, MD). First-strand complementary DNAs were synthesized from 5 µg RNA by using oligo dt primer and Thermoscript RT-PCR system (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). The PCR cycle was performed for in ducible heat shock protein 70 and β-actin from the same complementary DNA sample using a PCR Thermal Cycler (Gene Amp PCR System 9700, The Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, CT). The sequence of the oligonucleotide primers are as follows: sense inducible heat shock protein 70, 5’-TGCTGACCAAGATGAAG-3’; antisense inducible heat shock protein 70, 5’-AGAGTCGATCTCCAGGC-3’[24] and sense β-actin, 5’-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3’; antisense β-actin, 5’-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3’[25]. After-denatur-ation for 10 min at 95 °C, 30 cycles of amplification were carried out followed by final extension of 10 min at 72 °C, each step for 1 min. After amplification, 10 µL of PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide.

Immunohistochemical detection of inducible heat shock protein 70 in gastric mucosa[

26-30]

Fixed tissue sections (5 µm) were mounted on Vectabond Reagent-coated slides, deparaffinized and rehydrated through xyline, graded ethanol to distilled water. After blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3 mL·L-1 hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min, sections were treated with 0.05 mol·L-1 phosphate-buffered saline containing 30 mL·L-1 normal horse serum and 3 g·L-1 Triton X-100 for 30 min, then the sections were rinsed with PBS, incubated with mouse anti-rat monoclonal antibody (StressGen Biotechnologies Corp. Victoria, Canada, Cat# SPA-810) at dilution of 1:200 overnight at 4 °C in a humidity chamber. The secondary, biotinylated antibody (LSAB kit, Dako, Denmark) was then applied for 30 min followed by rinsing with PBS. Staining was performed by the addition of streptavidin (LSAB kit, Dako, Denmark) for 30 min, rinsed in PBS and developed in 3, 3’-diaminobendine tetrahydrochloride for about 3 min. Sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared and mounted.

Detection of inducible heat shock protein 70 proteins expression by Western blotting

The gastric mucosa were homogenized at 4 °C in RIPA buffer (50 mmol·L-1 Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mmol·L-1 NaCl, 1 g·L-1 sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 g·L-1 a-cholate, 2 mmol·L-1 EDTA, 10 g·L-1 Triton X-100, 100 mL·L-1 glycerol) containing 1 mmol·L-1 PMSF and 10 mg·L-1 aprotinin. After centrifuged at 10000 ×g at 4 °C for 20 min, the supernatant (50 µg of total protein) were denatured and separated on 75 g·L-1 sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA)[31,32]. The membranes were blocked with blocking buffer ( 50 mL·L-1) nonfat milk in wash buffer (20 mmol·L-1 PBS, pH7.5 containing 100 mmol·L-1 NaCl and 1 g·L-1 Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature, and subsequently incubated at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal antibody against rat inducible heat shock protein 70 (StressGen Biotechnologies Gorp. Victoria, Canada, Cat# SPA-810) diluted in blocking buffer (1:1000). Membranes were washed 6 times and incubated with a rabbit-anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with the horseradish peroxidase (1:4000) (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 1 h. After six times additional washes, membranes were developed by a commercial chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) and exposed to X-ray film. Protein determinations were made with Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Prestained molecular-weight standards (Bio-Rad) were used as markers.

Ethanol-induced gastric mucosal damage

Rats were starved for 24 h before 1mL of 500 mL·L-1 ethanol was administered orally to induce acute gastric mucosal damage[33]. Rats were killed 2 h later by a sharp blow on the heads followed by cervical dislocation. The stomach was removed and opened along the greater curvature. The gastric lesion area (mm2) was traced onto a glass plate and subsequently measured on a graph paper with 1 mm2 division[34]. The lesion index was calculated by dividing the total lesion area with the number of rats in each group.

Statistics

The data were statistically analyzed with the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

RESULTS

Sleep deprivation increase the expression of inducible heat shock protein 70

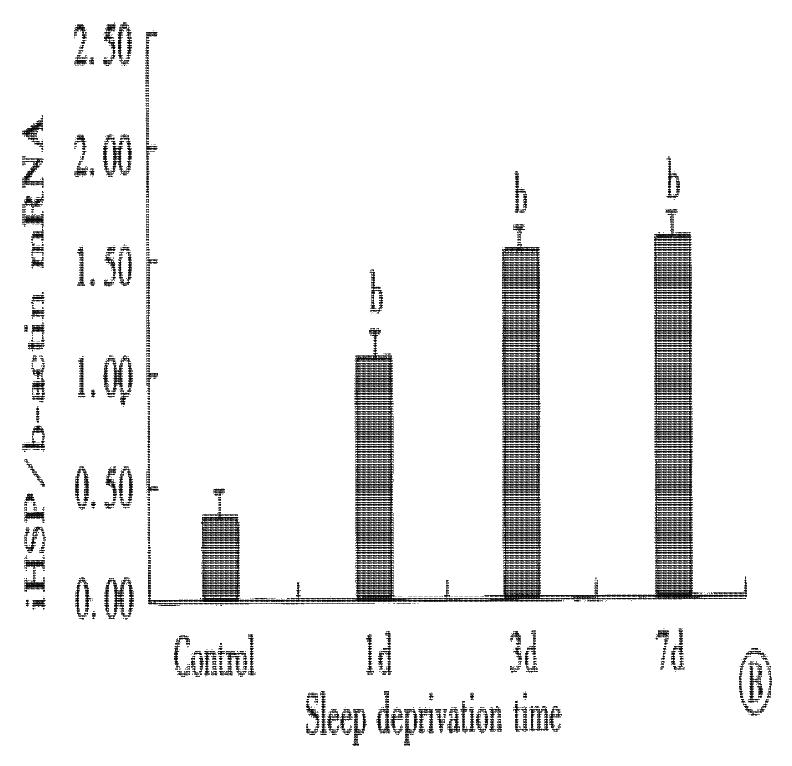

Total RNA and protein were isolated from rats’ gastric mucosa at various times of sleep deprivation. As shown in Figure 1, RT-PCR results indicated that the expression of inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA was low in normal gastric mucosa. Following the sleep deprivation, inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA expression was elevated. The pattern of inducible heat shock protein 70 protein accumulation showed a similar trend to mRNA expression (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Effect of sleep deprivation in inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA expression in gastric mucosa of rats.

Inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA was determined by RT-PCR. (A). Gel photograph of PCR-amplified inducible heat shock protein 70 and β-actin cDNA derived from inducible heat shock protein 70 and β-actin mRNA. Lane 1: normal control; Lane 2: 1 d sleep deprivation; Lane 3: 3 d sleep deprivation; Lane 4: 7 d sleep deprivation. (B). Bar graph showing the relative amount of inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA quantified by densitometry and expressed as mean of inducible heat shock protein 70 mRNA: β-actin mRNA ratios. Error bars represent SE, n = 8 for each group. bP < 0.01 vs control group.

Figure 2 Western blotting analysis of inducible heat shock protein 70 from gastric mucosa of sleep deprivation rats.

Lane 1 and 2: control; Lane 3 and 4: 1 d sleep deprivation; Lane 5 and 6: 3 d sleep deprivation; Lane 7 and 8: 7 d sleep deprivation.

Inducible heat shock protein 70 immunohistochemistry in gastric mucosa

To further prove that inducible heat shock protein 70 is increased in gastric mucosa of sleep deprived rats, confirm their expression at protein level, and determine their cellular sources, immunostaining for iHsp 70 was performed on gastric mucosa of sleep deprived rats and normal rats. The results showed that inducible heat shock protein 70 staining was nearly absent in normal mucosa but in mucosa of sleep deprived rats was detected in epithelium (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Inducible heat shock protein 70 immunohistochemistry in gastric mucosa of rats with 7 d sleep deprivation.

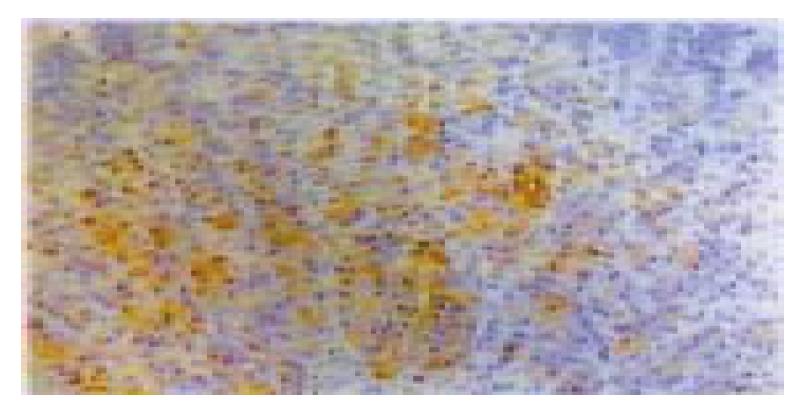

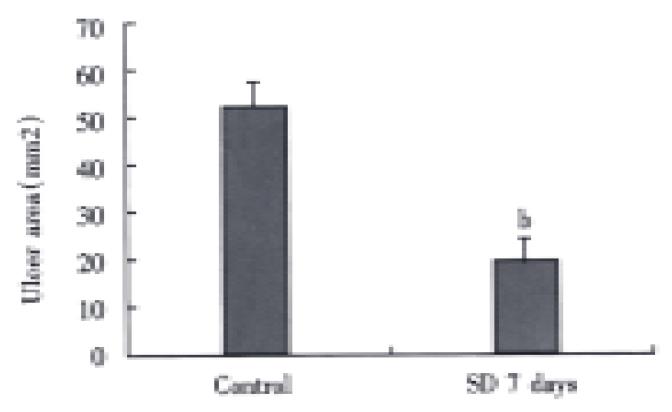

Sleep deprivation decrease ethanol induced gastric ulceration

After the 500 mL·L-1 ethanol challenge, the ulcer area found in the rats with 7 d sleep deprivation (19.2 ± 4.2) mm2 was significantly lower (P < 0.01) then the corresponding control (53.7 ± 8.1) mm2, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Effect of sleep deprivation in ethanol induced (50% ethanol 1 mL p.

o. for 2 h) gastric ulceration in rats. Error bars represent SE, n = 10 for each group. bP < 0.01 vs control group.

DISCUSSION

In our previously experiment, cDNA arrays were used to search for genes that were differentially expressed in gastric mucosa of sleep deprivation rats compared to gastric mucosa of control rats. More than 10 differentially expressed genes were found in total 588 genes, most of these were digestive enzyme related genes, one of the overexpression gene was inducible heat shock protein 70 gene[20]. A variety of chemicals, viruses, and noxious stimuli such as trauma, hypoxia, or ischemia trigger the heat shock response and the subsequent synthesis of heat shock proteins[35-43]. The results of our experiment indicated that sleep deprivation as a stress resulted in significantly greater expression of inducible heat shock protein 70 in gastric mucosa of rats, which was confirmed by RT-PCR, Western blotting and immunostaining. Substantial evidence showed that heat shock is capable of protecting cells, tissues and organs, and animals from a subsequent, normally lethal heating, as well as from other types of noxious condition[44]. The protective effect of heat shock is likely mediated by overexpressed heat shock protein 70, because there is a lag between heat shock and the development of protection correlated with the production of heat shock protein 70, and protection is affected when heat shock protein 70 production is inhibited by treatment with inhibitors[45-47]. Microinjection of anti-heat shock protein 70 antibody into fibroblasts to neutralize heat shock protein 70 increases the vulnerability of the cells to sublethal temperatures[48]. Furthermore, heat shock protein 70 also provides protection when induced by methods other than heat shock, such as rats that overexpress heat shock protein 70 induced by methods other than heat shock display protection of the lungs from sepsis-induced injury[49] and a reduction in hepatocyte apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-α[40]. Transgenic mice that overexpress heat shock protein 70 demonstrate resistance to adverse effects of lethal heat or ischemia[41]. Similar evidence has been derived from the study of cultured cells after heat shock or heat shock protein 70 gene transfection to promote overexpression of heat shock protein 70[50,51]. Our results showed that sleep deprivation was able to decrease the gastric mucosa damage caused by 50% ethanol. Although we cannot completely preclude the possibility that the vascular, neural, and hormonal factors may be involved in this mucosa protective effect, our previous work showed that sleep deprivation decreased the gastric mucosal blood flow, hampered the ability of the gastric mucosa to repair itself by slowing down its cellular replication rate, and depressed gastric potential difference. In conclusion, our results lead us to speculate that the heat shock protein 70 may play an important role in gastric mucosal protection.