INTRODUCTION

Primary gastric low-grade marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type is a distinct disease entity with a characteristic histological presentation and clinical behaviour[1]. The role of chronic Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma has become increasingly recognized. Thus MALT in the stomach is formed as an immunologic defense-system to control local infection caused by H. pylori. It is composed of antigen specific-reactive T-cells, plasma cells, some B-cells, and antigen-presenting, follicular, dendritic cells, and thus mimicing the lymphoid follicles known from other intestinal sites. Data were emerging to indicate that in fact low-grade MALT lymphomas in the stomach are a result of genetic changes probably affecting B-cells which clonally evolve from H. pylori related chronic gastritis[2]. There has been major progress in this area, including improvement of biopsy diagnosis, and especially, the start of a revolution in the treatment of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma by eradicating H. pylori that lead to a complete remission in about 80% of cases[3-8].

Despite decreasing numbers of gastric cancer in western countries, it is still the second most common cause of death due to a malignant disease world wide[9]. Serological investigations in 1990 revealed that a high prevalence of anti H. pylori IgG antibodies is associated with a high incidence of gastric cancer in South America and China[10,11]. Thereafter, many case control studies reported on a 3-6 fold increased risk for gastric cancer in H. pylori positive individuals[12-15]. Since there are many other factors that are important for the development of gastric cancer, i.e. low vitamin C level, gastric mucosal atrophy or hypergastrinaemia with an increase of nitroso compounds, the role of H. pylori is currently under investigation, thus the question if early eradication of the infection in high risk patients can prevent the development of gastric cancer[16,30].

Among the literature reviewed, only a few reports describe the development of synchronous gastric adenocarcinoma and primary gastric lymphoma[17-19]. However, only one report mentioned the probable co-factor H. pylori and the role of minimal invasive methods such as eradication therapy in the case of the lymphoma and endoscopic treatment for early gastric carcinomas[20]. The association of gastric lymphoma and the subsequent development of gastric adenocarcinoma is an exceptional finding, and has only been reported once with a gastric lymphoma of immunocytoma type in 1990 by a Spanish group[21].

In this paper, we reported 3 patients with H. pylori associated gastric MALT lymphoma who developed early gastric cancer 4 and 5 years, respectively, after complete lymphoma remission following cure of H. pylori infection.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

As reported earlier[5,7,22], 120 patients with primary gastric low-grade B cell MALT lymphoma in an early stage EI and H. pylori infection were included in the German MALT lymphoma trial starting from 1993. Cure of the infection leads to complete lymphoma remission in 79%, and partial remission in 10% of cases. Eleven percent of patients did not respond to antibiotic treatment.

Of the patients achieving complete lymphoma remission (n = 95; 79%) three developed an early gastric adenocarcinoma 4 and 5 years, respectively, after complete remission detected during routine follow-up endoscopy. Patient 1 (#1), a 74-year-old male, was included in the trial in March 1995 presenting with a gastric ulcer in the antrum and was treated in accordance to the protocol receiving antibiotic medication[5]. Four weeks later, the infection was cured, and after another 8 weeks, the patient achieved complete lymphoma remission. During the first year of follow-up, the patient was endoscoped every 3 months. Biopsy specimens were obtained each time and examined for continuous complete lymphoma remission and absent H. pylori colonization. Endoscopic controls were then performed twice a year. In June 1999, 4 years after complete lymphoma remission, routine control endoscopy showed a small flat elevation at the same location of the stomach where the MALT lymphoma ulcer was diagnosed 4 years earlier. Biopsies obtained from this area revealed an tubular adenoma partially transformed into a well-differentiated early gastric adenocarcinoma of the mucosa-type (m-type), 4 mm in diameter, type IIa, intestinal type in accordance to the Laurén classification[23], UICC Ia (pT1G1pN × M × R0). H. pylori could not be detected either in the antrum or corpus mucosa. The early gastric adenocarcionoma was removed by endoscopic mucosa resection (EMR). Staging procedures revealed an adenocarcinoma of the left colon that was removed by surgery.

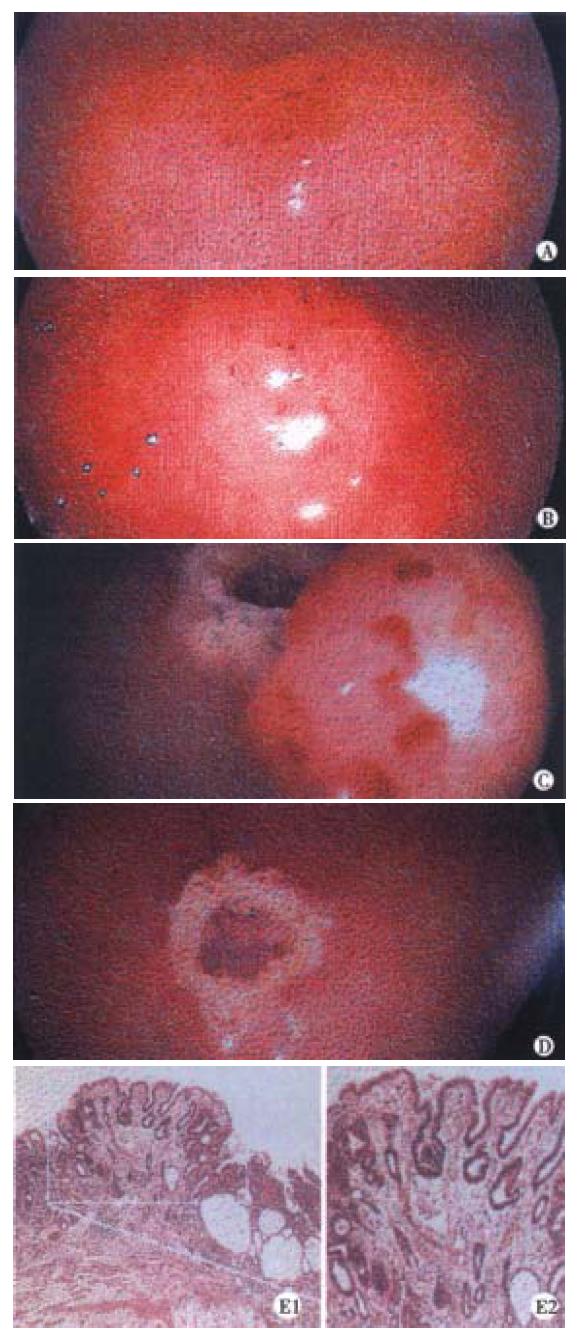

The second patient (#2), a 77-year-old woman, entered the MALT lymphoma trial in December 1995. Thirteen years earlier, the woman was diagnosed suffering from nodal Hodgkin’s disease stage II b that was initially successfully treated with chemotherapy. In 1994, the Hodgkin’s disease relapsed and the patient received another course of chemotherapy. In December 1995 she presented with a gastric ulcer at the angulus. Biopsy specimens revealed an early stage H. pylori-associated low-grade MALT lymphoma and she was enrolled in the study receiving antibiotic treatment. As described in patient #1, she underwent routine endoscopic control examinations after achieving complete lymphoma remission. Four years later, surveillance endoscopy revealed a complete erosion, 6 mm in diameter, opposite the ulcer scar where the MALT lymphoma was diagnosed with H. pylori negative. Biopsy specimens showed a well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma of the mucosa-type (m-type), 6 mm in diameter, type II c (according to the Japanese classification), intestinal type based on the Laurén classification[23], UICC I a (pT1G1pN × M × R0) that was removed by EMR (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Endoscopic mucosa resection (EMR) in patient #2.

A. Early gastric adenocarcinoma (EGC) in the antrum; φ 0.4 cm, m-type, B. EGC in the antrum; φ 0.4 cm, m-type after injection of suprarenine, C. Mucosa after EMR, D. Ulcer after EMR, treatment with argon beamerplasma coagulation, E. H&E stain of the endoscopically resected mucosa showing a gastric intestinal type adenocarcinoma, restricted to the mucosa (m-type)

The third patient (#3), a 70-year-old man, was diagnosed having an H. pylori associated low-grade MALT lymphoma in the upper corpus region in October 1994. He received antibiotic treatment and achieved complete lymphoma remission 12 months after cure of the infection. The patient was followed up in accordance to the protocol[5], and surveillance endoscopy 5 years after complete remission of the gastric MALT lymphoma revealed three flat elevations in the prepyloric antrum mucosa, approximately 5-6 mm in diameter. Endosonographic ultrasound revealed a mucosa-type tumor, and biopsies obtained during gastroscopy showed infiltrates of an intestinal type (Laurén) early gastric adenocarcinoma type II a and II c (Japanese classification), UICC Ia (pT1G1pN × M × R0). EMR was performed as well as additional argon plasma coagulation.

All histological evaluations were done by one central pathologist (M.S.). Sections were stained with H&E to grade gastritis, and Warthin-Starry stain to detect and grade colonization with H. pylori. Grading of the varibles of gastritis was done using the Sydney system[25], with slight modifications characterized by using a scoring system ranging from 0 = none to 4 = severe, and including the degree of replacement of foveolae by regenerative epithelium as an additional variable[26].

RESULTS

Briefly, 120 patients with primary gastric low-grade B cell MALT lymphoma in an early stage EI and H. pylori infection were included in the German MALT lymphoma trial starting in 1993. Cure of the infection leads to complete lymphoma remission in 79% (n = 95), and partial remission in 10% (n = 12) of cases. Eleven percent of patients (n = 13) did not respond to antibiotic treatment probably because of more advanced stages that were initially undergraded, or high-grade tumor components that were undetected[22]. Nine patients showed a lymphoma relapse, 8 local and 1 distant, 128 to 481 days after complete remission all but 1 H. pylori negative. The median follow-up time was 32 months.

Within the group of patients achieving complete lymphoma remission (n = 95; 79%) three patients aged 70-77 years, two men and one man, developed an early gastric adenocarcinoma 4 and 5 years, respectively, after complete remission detected during routine follow-up endoscopy, comprising an incidence rate of 3.15%. Based on the median follow-up time of 48 months, the annual risk for the development of a gastric adenocarcinoma following complete remission of gastric MALT lymphoma is 0.78%. In all patients, minimal invasive methodssuch as eradication therapy in lymphoma, diagnosed early and endoscopic treatment for early gastric carcinoma was employed (Figure 1). Endoscopic treatment of the carcinoma with EMR resulted in R0 resection of the cancer, and a follow-up examination 6 months after EMR in patients #1 and #2 revealed no remnant carcinoma infiltrates.

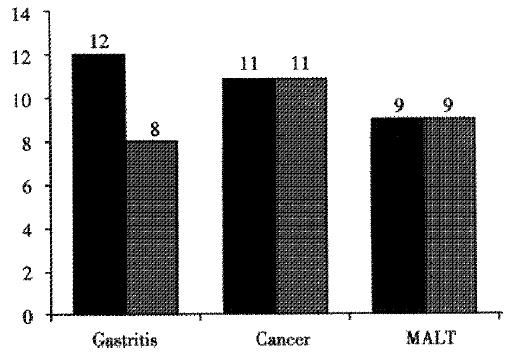

At the time of diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma, none of the patients showed H. pylori infection. In two patiens, the carcinoma was diagnosed near an area with intestinal metaplasia and signs of focal atrophy (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Medians of the summed gastritis score in antrum and corpus, formed by adding together the respective values of grade and activity of gastritis, replacement of foveolae by regenerative epithelium, and density of H.

pylori colonization as presented in Reference 24.

DISCUSSION

The association of primary gastric MALT lymphoma and the subsequent development of gastric adenocarcinoma is an exceptional finding. In the review of the literature, we have found only 1 case of this subsequent association with an immunocytoma type gastric lymphoma[21]. The patient was treated with subtotal gastrectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy and developed an adenocarcinoma of the gastrojejunal anastomosis. As no one looked for H. pylori infection at that time the implicated factors in the development of this association are gastric resection and radiotherapy, and as it was also speculated, the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma itself. Reports on simultaneous MALT-type lymphoma and early adenocarcinoma of the stomach are more frequent[17-20]. It was speculated for a long time that patients with Hodgkin’s disease and nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma seem to have an excess risk for other cancers, and a high incidence of other cancers (20%) has also been found in some series of patients with gastric MALT lymphomas[27]. Montalbán and co-workers[28]were able to show that in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, other cancers do occur, but that there is no increase in risk above the background population. Among 136 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, other cancers were detected in 11.7%, either prior to the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma, concomitantly or after diagnosis. Of all 136 patients investigated, only 53 had not received chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery as implicated factors, and of those, 2 (3.7%) patients developed a gastric adenocarcinoma. This cumulative incidence is in line with the cumulative incidence we report in this paper, that is 3.15% (3/95 patients).

The observation of concurrent or subsequent gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma is of interest as both are etiologically related to H. pylori. For gastric MALT lymphoma, the causative association with this chronic stimulus is well established, and cure of the infection can lead to complete remission of early lymphoma in about 80% of cases[5,7,8]. As indicated earlier, serological investigations demonstrated a high prevalence of anti H. pylori IgG antibodies in an area with a high incidence of gastric cancer[10,11], and many case control studies reported on a 3-6 fold increased risk for gastric cancer in H. pylori positive individuals[12-15]. In one report analysing synchronous adenocarcinoma and low-grade B-cell MALT lymphoma, H. pylori was seen in 7 (78%) of 9 cases which is consistent with an etiological role for this organism in both tumors in the stomach[18].

Primarily on the basis of this epidemiological evidence, H. pylori has been classified as a definite human carcinogen in 1994[29]. Although several pathophysiological mechanisms have been identified which may contribute to the development of gastric carcinoma, the role of H. pylori eradication for disease prevention is currently under investigation[16,30]. The aim of these studies is to test the hypothesis that H. pylori eradication alone can reduce the incidence of gastric cancer in a subgroup of individuals with an increased risk for developing gastric adenocarcinoma. A non-randomized Japanese study on 132 H. pylori positive patients with early gastric cancer who had undergone endoscopic mucosa resection showed that after additional H. pylori eradication therapy, no new early gastric cancer occurred during 2 years. Another 2 years later, i.e. 4 years after eradication therapy, one of these patients so far has developed a second gastric cancer. However, among those who remained infected, there was a 9% recurrence rate of early gastric cancer[33,34]. Whether H. pylori eradication can lead to regression of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, histological risk markers for gastric cancer, is still controversial[16]. Based on all these evidences and, hence, the idea of a possible prevention of the development of gastric adenocarcinoma by curing chronic H. pylori infection, it is surprising that 3 patients within our MALT lymphoma trial developed gastric carcinoma despite eradication of the bacterium 4 and 5 years earlier in the scope of treating the gastric MALT lymphoma. These data may indicate that H. pylori eradication alone might not be sufficient to prevent cancer. However, it might have been successful, if cure of the infection probably occurred earlier in life. The timing of treatment might be crucial for the determination if the development of gastric adenocarcinoma can be prevented by H. pylori eradication alone. Although our report suggests that gastric cancer may still occur after H. pylori eradication, these data can not be transferred to the general population since those patients already had a gastric malignancy.

Based on the findings that MALT lymphoma patients, in fact, do not have an increased risk of additional neoplasms, there is no need to invoke or be concerned about general genetic instability of the host as a possible underlying mechanism for lymphoma-and/or carcinogenesis. Differences in the characteristics of H. pylori strains as well as different environmental factors in the infected hosts seem also being involved in the variable outcome of the infection[31,32]. Recently, a corpus-dominant distribution of H. pylori gastritis has been recognized as a histological gastric cancer risk marker, and studies concerning the degree and distribution of H. pylori have shown significant differences among H. pylori associated diseases[24]. As it was demonstrated by Meining et al[24], in both malignant diseases investigated, gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric MALT lymphoma, the extent of gastritis was equal in the corpus and in the antrum mucosa. Thus both malignant diseases differ from the benign gastritis only in the extent of the gastritis in the antrum and corpus part of the stomach. Furthermore, the overall extent of gastritis in MALT lymphoma patients was not as severe as in patients who had a carcinoma or gastritis only. Gastric atrophy was much more frequent in gastric cancer patients than in MALT lymphoma patients (42% vs 6% in the antrum mucosa, 18% vs 4% in the corpus mucosa)[24]. The three patients with gastric adenocarcinoma presented here also have a gastritis equally expressed in the corpus and antrum mucosa but of a milder degree. The carcinomas diagnosed were found near or within intestinal metaplasia in two cases of consecutive atrophy, the histological risk markers for early gastric cancer. The exact reasons for the differences in distribution and degree of gastritis in different H. pylori associated diseases have not yet been fully understood. It seems possible, that patients developing a minimal to mild gastritis, equally distributed in the antrum and corpus mucosa are likely to have a higher risk of developing a gastric MALT lymphoma.

Our study population included 56 men and 64 women with a median age of 65 years (a range of 29-88 years). The three patients developing a gastric adenocarcinoma were 70, 74, and 77 years old, respectively. The incidence of cancer in the general population increases continuously with age, affected by changing patterns of population screening and intensity of attempts at cancer detection, and is about 120 for men and 50 for women in this age group in Germany. The relatively high median age in our MALT lymphoma study group is therefore, independently of other risk factors, associated with a high cumulative incidence of cancers. Appreciating the apparent increase in cancer incidence brought about by better screening methods and earlier detection, and comparing our results to a defined general population with accurately known cancer incidences, there is still to state that the association of primary gastric MALT lymphoma and the subsequent development of gastric adenocarcinoma is an exceptional finding, and that H. pylori gastritis must be considered to be associated with the development of these two malignancies with an approximately 6-7 fold increase of the overall incidence.

All cancers of our three patients were detected during routine surveillance endoscopy. Endoscopy was performed in each patient twice yearly in accordance to the MALT lymphoma protocol since these patients have achieved complete lymphoma remission after cure of H. pylori infection. Early gastric adenocarcinoma was detected 4 and 5 years after complete remission of lymphoma. Due to the early stage diagnosis of the gastric cancer, endoscopic therapy (mucosal resection = EMR) was successfully performed in each case. In contrast to most cases of synchronous MALT lymphoma and gastric carcinoma, the definite diagnosis of gastric lymphoma and carcinoma was obtained preoperatively. As it has been also stated by Müller et al[20], this seems to be in future times an essential prerequisite for employing minimal invasive methods such as eradication therapy in the case of the diagnosed early lymphoma and endoscopic treatment for early gastric carcinomas. This management of the diseases seems to be benefical and effective especially with regard to the life quality of the patients. However, to apply this treatment strategy, it is important to perform regular long-term follow-up endoscopies in patients with complete remission of gastric MALT lymphoma after cure of H. pylori infection.