INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common infectious agent associated with post-transfusion and community-acquired non-A-non-B hepatitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis[1]. Up to 85% of patients with acute HCV infection will develop chronic liver disease and spontaneous viral elimination is rare[2]. In studies with a follow up of 10-20 years, cirrhosis secondary to chronic HCV infection develops in 20%-30%[2,3] and is the most common indication for liver transplantation worldwide[4]. Patients with cirrhosis secondary to chronic HCV infection also have an increased risk for development of hepatocellular carcinoma, estimated to be between 1%-4% per year[5]. The introduction of alpha interferon (IFNα) for the treatment of HCV infection is an outstanding revolution in antiviral therapy [6]. However, alpha interferon monotherapy strategies can only induce a sustained response in 8%-21% of the patients with chronic HCV-related liver disease[7]. Thus, new therapeutic strategies were needed for chronic HCV infection in order to increase the sustained response rate in naive patients and patients in whom the response to standard alpha interferon monotherapy was ineffective, in particular the relapsers and non-responders.

Systemic ribavirin (1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1, 2, 4-triazole-3-carboxamide), a broad-spectrum oral purine nucleoside analogue, has been used for the treatment of a variety of viral diseases[8]. In children with viral diseases, ribavirin is usually given orally at a dosage of 10 mg/kg daily[8]. In adult human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients, ribavirin plasma levels between 6 and 12 µmol/L are required to achieve viral inhibition with acceptable toxicity[9]. Daily oral doses of 600 (1200) mg ribavirin resulted in a mean peak plasma concentration of 5.0 (11.1) µmol/L at the end of the first week. Clinical and hematologic toxicities were not noted at a ribavirin dosage of 600 mg/d for 2 weeks, but a dosage of 1200 mg/d for 2 weeks resulted in moderate to severe clinical and hematological adverse events (hematocrit decrease)[9]. Furthermore Glue et al[10] reported similar ribavirin pharmacokinetics comparing pediatric and adult patients.

In patients with chronic HCV infection, ribavirin monotherapy has been found to improve serum levels of hepatic transaminases and liver histology by decreasing hepatic inflammation and necrosis[11-13]. In 1991, oral ribavirin treatment in a dosage of 1000 mg/d for chronic HCV-infected patients weighing less than 75 kg and 1200 mg/d weighing more than 75 kg for 12 weeks was evaluated in a pilot study[14]. In 1994 and 1995, the first promising reports[15-18] on the combined therapy with alpha interferon and ribavirin in a dosage of 1000-1200 mg/d orally according to Reichard et al[14] were obtained in relapsers and non-responders as well in naive patients with chronic HCV infection. Therefore, we started a combination treatment with interferon alfa-2a (IFN) in non-responders and relapsers to IFN monotherapy. However, we used a lower dosage of oral ribavirin (10 mg/kg body weight daily) according to that used in child[8] and adult[9] HIV-infected patients and to pharmacokinetic studies performed in healthy volunteer and patient populations[10]. Duration of the combined therapy was 6 months, followed by a 6-month treatment with IFN monotherapy for responders to combined therapy in chronic HCV-infected patients who were previous non-responders or non-sustained responders (relapsers) to IFN alone. The results of safety, tolerability and virological efficacy during and after treatment are reported.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Fourty-seven chronic HCV-infected patients (15 female, 32 male, mean age 48 years) with histological mild chronic hepatitis ( n = 17), moderate chronic hepatitis (n = 18), severe chronic hepatitis (n = 5), cirrhosis (n = 5) and unknown histology (n = 2) received antiviral therapy. HCV genotypes were classified in 10 patients as I (1a), in 30 as II (1b), in 2 as IV (2b), in 4 as V (3a), and one was unclassifiable according to Okamoto[19] and Simmonds[20]. The cause for HCV transmission could be identified as lood-transfusions (n = 13), injection drug use (n = 3), occupational (n = 2), sexual/household (n = 1) and unknown (n = 28). All patients had been previously treated with IFN. Thirty-four patients had not responded. Non-response to the first IFN therapy was defined as the persistence of at least 3 abnormal aminotransferase activities during a course of at least 3 months of IFN treatment with monthly control and after IFN discontinuation, and by PCR which remained positive [21]. Thirteen patients had an initial response to a dose of 3-6 million units three times per week for at least 20 weeks but not more than 18 months[22], followed by relapse. The IFN treatment was discontinued for at least 3 months before the combination therapy was started. All patients had persistent elevations of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), a positive third-generation anti-HCV test using an immunoblot procedure (CHIRON RIBA HCV 3.0 SIA, Ortho Diagnostic Systems Inc., Raritan, USA) and positive serum HCV RNA by reverse transcriptase/polymerase chain reaction (RT/PCR). Patients with decompensated liver disease, autoimmune disorders, thyroid gland alterations, active alcohol or injection drug abuse, history of major psychiatric disease, pregnancy, significant anemia (hemoglobin < 12 g/dL), leukocytopenia ( < 3000 µL)or thrombocytopenia ( < 50000 µL) were not included. Active hepatitis A virus, HIV, hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus or Ebstein-Barr virus infections were excluded by convential laboratory tests. Informed consent was obtained in all treated patients.

Treatment

Combination therapy was given for 6 months with IFN and ribavirin. The IFN dose was adjusted to the previous IFN treatment. Twenty-two of 34 previous non-responders were treated with 6 MU subcutaneous (s.c.) t.i.w. and 12/34 with 3 MU t.i. w.. Eleven of 13 previous relapsers were treated with 6 MU t.i.w. and 2/13 with 3 MU t.i.w.. To improve virological efficacy and tolerability instead of using ribavirin at a dose of 1000-1200 mg/day, we administered ribavirin at 10 mg/kg body weight daily in three divided doses orally. This dose was chosen in accordance to the tolerability data obtained in HIV-infected children[8] whose pharmacokinetic data are similar to those obtained in adults[10] and in HIV-infected adults[9]. Patients who responded to the combination therapy were treated for another 6 months with IFN monotherapy with the same preceeded dose (3 or 6 MU s.c. t.i.w.). After 12 months of treatment, the patients were followed up for at least 9 months.

Monitoring

Clinical examination, total blood cell counts, routine biochemical tests and detection of serum HCV RNA by RT/PCR were performed before and at monthly intervals during and after 6 months treatment, thereafter every 3 months.

Detection of serum HCV-specific RNA by RT/PCR

RNA was extracted from serum samples (140 μL) using the QIAamp viral RNA KIT (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One-fifth of the extracted material from serum was subjected to a nested RT/PCR procedure essentially as described[23].

Determination of HCV genotypes

HCV genotypes were determined according to Okamoto et al[19] using RT/PCR with a type-specific primer of the core region. Genotypes determination was then confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion analysis as described previously[24].

RESULTS

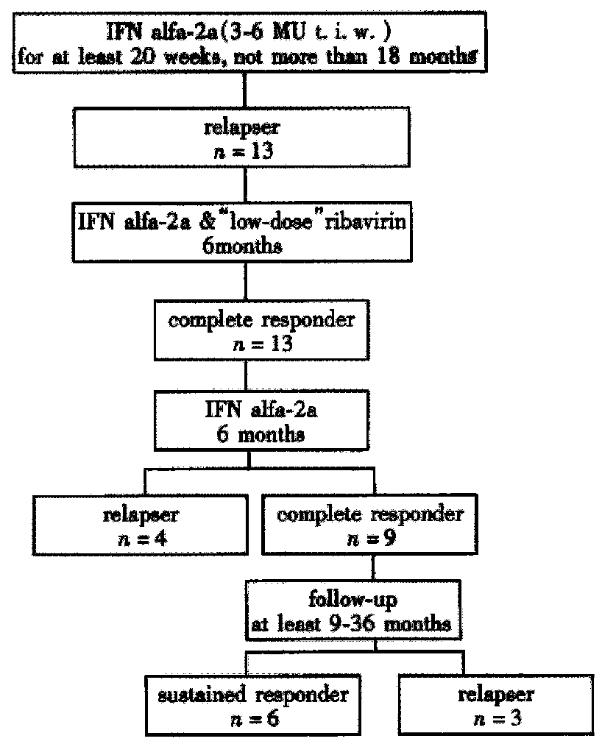

Response to previous IFN monotherapy, combination therapy with IFN and ribavirin, subsequent IFN monotherapy for responders to combination therapy and outcome during follow-up for previous non-responders is depicted in Figure 1 and for previous relapsers in Figure 2.

Figure 1 Outcome of 34 HCV infected non-responders to IFN monotherapy, including response to combined therapy with IFN and “low-dose” ribavirin for 6 months, response to followed IFN monotherapy for 6 months for complete responders to combined therapy and outcome during follow up after 12 months treatment.

Figure 2 Outcome of 13 HCV-infected relapsers to IFN monotherapy, including response to combined therapy with IFN and “low-dose” ribivirin for 6 months, response to followed IFN monotherapy for 6 months for complete responders to combined therapy and outcome during follow-up after end of 12 months treatment.

Drop-outs

Seven of 34 non-responders to previous IFN monotherapy (20.6%) stopped the combination therapy because of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (n = 1), sarcoidosis (n = 1), lichen ruber oris mucosae (n = 1), severe fatigue (n = 1) or depression and fatigue (n = 3). Two of seven drop-out patients had a histological and clinical Child A cirrhosis. During combination therapy and after withdrawal, transaminases remained unchanged at elevated levels and serum HCV RNA was still positive in all patients. There were no drop-outs in the 13 relapsers to the previous IFN monotherapy.

Outcome of combination treatment (6 months)

Twenty-seven non-responders to previous IFN monotherapy continued on the 6-month course of combination therapy. At the end of the 3 months, 17/27 (63%) patients did not respond to the combination therapy with unchanged elevated transaminases and positive serum HCV-RNA, so therapy was stopped. Ten of 27 (37%) had a complete response with transaminases in the reference ranges and negative serum HCV RNA.

All 13 relapsers to previous IFN monotherapy completed the 6-month course of combination therapy. At the end of 6 months, 13/13 (100%) patients had a complete response with transaminases in the reference ranges and negative serum HCV RNA.

Outcome of complete treatment (12 months)

The 10 non-responders to previous IFN monotherapy, who had a complete response at the end of combination therapy were treated with the same dose of IFN used before as monotherapy for a further 6 months . During the 6-month course of IFN monotherapy, 4/10 (40%) patients had a relapse within 6-months after the end of ribavirin treatment. Six of ten (60%) patients still had a complete response at the end of 12-month treatment course with transaminases in the reference ranges and undetectable serum HCV RNA.

All 13 relapsers to previous IFN monotherapy had a complete response at the end of combination therapy and were treated with the same dose of IFN used before as monotherapy for a further 6 months . During the 6-month course of IFN monotherapy, 4/13 (31%) patients had a relapse within 6 months after ribavirin treatment. Nine of 13 (69%) patients still had a complete response at the end of 12-month treatment with transaminases in the reference ranges and undetectable serum HCV RNA.

Follow-up (at least 9 months)

At the end of the 12-month treatment, 6 non-responders to previous IFN monotherapy became complete responders. At a mean follow-up of 28 months (16-37 months), 2/6 (33%) patients relapsed, 4/6 (67%) were sustained responders, including one patient with genotype II (1b) and cirrhosis.

At the end of 12-month treatment, 9 relapsers to previous IFN monotherapy became complete responders. At a mean follow-up of 22 months (9-36 months), 3/9 (33%) patients relapsed, 6/9 (67%) were sustained responders with transaminases in the normal range and undetectable serum HCV-RNA.

In summery, 4/27 previous non-responders (15%) and 6/13 previous relapsers (46%) are sustained responders.

Side effects

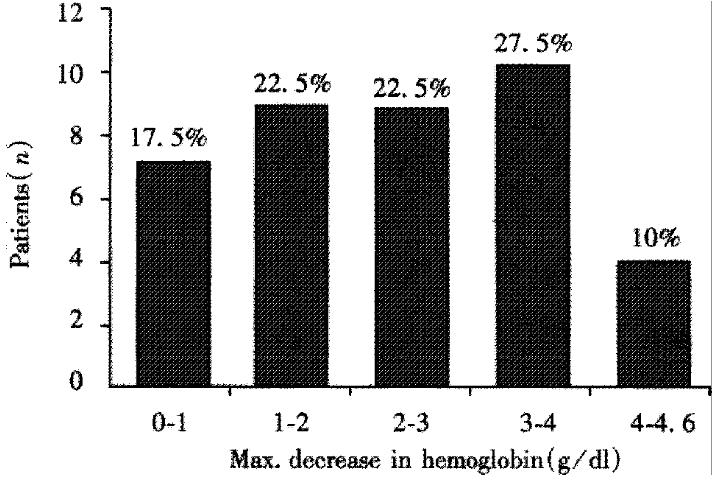

Combination therapy with IFN (3-6 MU s.c. t.i.w.) and “low-dose” ribavirin (10 mg/kg body weight) was well tolerated. Monitoring of side effects by questioning and clinical examination revealed arthralgia in 77%, fatigue in 27% and loss of weight in 19% of the patients. The most prominent side effects of combination therapy were alterations in total blood cell counts. Mild leukocytopenia (minimal 2000/μL in a patient without cirrhosis and 1400/μL in a patient with cirrhosis) and thrombocytopenia (minimal 79000 μL in a patient without cirrhosis and 35000 μL in a patient with cirrhosis) were generally seen. Decreases in hemoglobin is shown in Figure 3. Of 40 patients who continued on combination therapy 7 patients were withdrawn. There was no need of transfusion or drug dose reduction. All side effects were completely reversible within one month after treatment.

Figure 3 Decrease of hemoglobin of 40 patients (34 non-responders and 13 relapsers to IFN monotherapy) who continued on combination therapy with IFN and “low-dose” ribavirin.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective uncontrolled analysis, we report on our experience of 47 chronic HCV-infected patients who received a combination treatment of IFN and “low-dose” ribavirin after previous failure to IFN monotherapy. Of the 47 patients, 34 were non-responders and 13 relapsers to the initial IFN monotherapy. Seven of 34 (20.6%) non-responders to the previous IFN monotherapy (two with histological cirrhosis), did not complete the 6 months course of combination therapy due to various side effects, but none of the 13 relapsers to previous IFN monotherapy. In comparison to our results, a meta-analysis of individual patient data from European centers revealed that about 10% of patients withdrawn from treatment[25]. Although our results have the drawback of being obtained under uncontrolled conditions, they have the advantage of being more realistic as every day experience is often different from that obtained under controlled study conditions.

In our patients, we found that a 6-month course of combined therapy with “low-dose” ribavirin induced a complete response at the end of treatment in 10 (37%)of 27 initial non-responders. In a similar retrospective analysis, 2 (12.5%) of 16 non-responders to IFN monotherapy were complete responders at the end of combination therapy and both patients relapsed during the follow - up period[26]. From our initial 13 relapsers to IFN monotherapy, 13 (100%) were complete responders at the end of 6-month combination treatment with “low-dose” ribavirin, in contrast to the multicenter study from Davis et al, who found 77% complete responders at the end of 6-month combination treatment with ribivarin in a dose of 1000-1200 mg per day depending on body weight[22].

Previous publications had suggested that duration of therapy longer than 6 months may reduce the number of relapsers[16,27]. Therefore, the 23 complete responders (10 initial non-responders and 13 relapsers to IFN monotherapy) at the end of 6-month combined therapy continued with IFN alone for another 6 months. Eight of 23 (35%) complete responders at the end of combined therapy with “low-dose” ribavirin (4 initial non-responders and 4 relapsers to IFN monotherapy) relapsed under IFN monotherapy within 3 months, suggesting that in a subgroup of patients a longer course of combined therapy could leed to sustained response.

During the follow-up period, 5 of 15 (33%) complete responders at the end of 12 months treatment (2 initial non-responders and 3 relapsers to IFN monotherapy) relapsed within 3 months. Also, these patients represent a subgroup who may benefit of a longer period of combined therapy. However, 4/27 (15%) initial non-responders (including one with histological cirrhosis and genotype I (1b) and 6/13 (46%) relapsers to IFN monotherapy were still complete sustained responders (16-37 months follow-up for initial non-responders and 9-36 months for initial relapsers to IFN monotherapy) after 12 months treatment.

A combined therapy with IFN and “low-dose” ribavirin for 6 months followed by 6 months of IFN monotherapy in those patients who responded to the combination therapy can induce sustained response not only in relapsers to IFN monotherapy, but also in some non-responders, among whom, one patient had histological sign of cirrhosis and genotype I (1b). This result is noteworthy as the monotherapy course was performed with a total amount of IFN which was previously shown to be effective in a large number of patients[27]. This suggests that retreatment with a higher dose of IFN for a longer period[28-30] is less promising than the combination therapy. Our experience also shows that a further 6 months of IFN monotherapy after combination therapy may help reduce the number of relapsers and that on the other hand the duration of the combination therapy of 6 months may not be sufficient for some patients. The results of this retrospective analysis are difficult to compare with those recently published by Sostegni et al[31], Davis et al[22], Pol et al[21] and by Milella et al[32] obtained treating patients who were non-responders to[21,31,32] or relapsed after[22,32] interferon alfa monotherapy with a combination therapy for 6 months, because the number of non - responders and relapsers we treated is small. However, it is also noteworthy that the lower dose of ribavirin we used seems to allow response rate may similar to those recently published in controlled studies[21,22,31,32]. This strategy received support in a recently presented abstract[33] where a ribavirin dose of 600 mg/day was as effective as 1000 mg/day as for as week 12 HCV RNA levels concerns during alpha interferon and ribavirin therapy in chronic HCV-infected patients. This is also of economic relevance as the ribavirin released into the market recently increases the costs of about 1000 Dollars per month. Our results may stimulate a prospective study where complete responders under combination therapy are treated for further 6 months with alpha interferon alone as has been recently suggested by Perasso et al[34].

In conclusion, combination therapy with “low-dose” ribavirin may represent a therapeutic alternative for at least some non-responders and relapsers.