MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, the Chinese Academy of Sciences) were allowed to acclimate to our laboratory conditions for at least 5 d. The animals were fed standard commercial rat pellet chow, which contained crude protein 25%, fat 10%, crude fiber 50%, calcium 1.0%, phosphate 0.8% (Jiangsu Province Jiangpu Laboratory Animal Feeds Factory, Nanjing, China) and tap water ad libitum. Constant room temperature (22 °C) with 12 h light and dark cycles were supplied. The experiment protocols described below were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinling Hospital.

Experimental design

After an overnight fasting, all animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg). Resect-control animals (n = 10) and growth hormone-resect (GH-resect) animals (n = 10) underwent 80% mid-small bowel resection, leaving 7 cm of proximal jejunum and 7 cm of terminal ileum. Control-transect animals (n = 10) underwent bowel transection of ileum 7 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. Postoperatively, animals were allowed to drink water libitum on the first day, and chow on the beginning of the second postoperative day. Somatropin (1 IU/kg) (Saizen, Laboratories Serona S.A., 1170 Aubonne, Switzerland) was administered subcutaneously once daily at 16:00 from the first postoperative day to the day of killing. All animals were sacrificed at about 08:00 to 10:00 on the 29th postoperative day. Residual ileum from 2 cm distal to the anastomosis to the ileocecal valve was excised and luminal contents were removed. In transected animals anatomically similar segments were removed. The first 1 cm of the excised ileum was for histological analysis. The mucosa of the following 2 cm segment was scraped for nuclear acid analysis. And the mucosa of the remaining ileum was scraped for flow cytometric analysis.

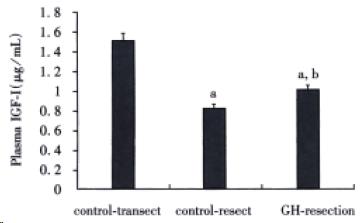

Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) determination

Total plasma IGF-I concentrations were measured after acid-ethanol extraction with the use of DSL-2900 rat IGF-Iradioimmunoassay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories Inc., Webster, Texas, USA).

Mucosal histological image analysis and immunohistochemical assay for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)

Fixed specimens of ileum were embedded in paraffin and oriented to provide cut sections parallel with the longitudinal axis of the bowel. Four-micrometer-thick slices were mounted and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Villus height, crypt depth and mucosal thickness were measured using a video assisted integrated computer program (HPIAS-1000 True Color Image Analysis System). Villi were chosen on the basis of the ability to completely visualize the central lymphatic channel and crypts to visualize the crypt-villus junction on both sides of the crypt. At least 15 villi and crypts were counted per sample.

The immunohistochemical staining for PCNA was performed by Labeled Streptavidin-Biotin method (S-P) with staining kit (Fuzhou Maxim Biotech, Inc., Fuzhou, China) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Those cells with brown-stained nuclei were reckoned as positively stained cells. The PCNA index was measured as a percentage of the number of positively stained cells over the total number of cells in the crypt. Five high-resolution fields from each slide were randomly chosen for measurement.

Flow cytometric analysis

Freshly scraped small bowel mucosa was mechanically dispersed through wire mesh and collected into cold (4 °C) phosphate buffered solution (PBS). The cell suspension was washed and filtered through 60 μm nylon mesh and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106 cell/mL. Aliquots of 1 mL mucosal cell suspension were centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min and the cell pellets were subjected to DNA labeling with method described in[13]. The stained cells suspension was analyzed using an Epics XL flow cytometer (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL, U.S.A.). The percentages of cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle were determined. The cell proliferative activity was measured by proliferative index (PI), calculated by (S + G2/M)/(G0/G1 + S + G2/M) × 100%.

Semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the ileal mucosa using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Concentrations of total RNA were determined spectrophotometrically at A260. RT reactions were carried out using 2.5 μg of total rat RNA and a cDNA synthesis kit (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) in a final reactionvolume of 20 μL. Synthetic oligonucleotides (Sango Biotech. Corp., Shanghai, China) for cDNA amplification were as follows: 5’-gcatgaggaaccgcattgccgcctccaagt-3’ (sense), 5’-cgcacagtctgccggccaataggccgct-3’ (anti-sense) for C-jun and 5’-catttccggtgcacgatggag-3’ (sense), 5’-ggcatcctgcgtctggacctg-3’ (anti-sense) for β-actin respectively. The PCR amplified products were of 459-base-pair for C-jun cDNA and 599-base-pair for β-actin cDNA respectively. PCR was performed using 6.0 μL of reverse transcription product and a master mixture containing 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH8.8), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 75 mmol/L KCl, 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs, 5’ and 3’-C-jun-oligon-ucleotides (0.25 μmol/L each), 5’ and 3’β-actin oligonucleotides (0.25 μmol/L each), and 2.0 unit Taq polymerase (GIBCOBRL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.). The samples were denatured initially at 94 °C for 5 min. Amplification was performed on Gene Cycler (Bio-Rad, Japan). The cycling condition was selected for β-actin as denaturating at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 58 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min for 28 cycles; for C-jun as denaturating at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 61 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min for 33 cycles. The final cycle was followed by an extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR amplifiers were subjected to electrophoresis through 1.6% agarose gel containing 0.5 mg/L ethidium bromide, visualized by ultraviolet illumination. The electrophoresis gel images analyzed with Kodak Digital Science 1D Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.). The expression of C-jun was measured as a ratio compared with β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. Possible post hoc comparison of pairs of means was conducted by Ducan’s multiple range test. A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

DISCUSSION

Our animal experiment demonstrated that small bowel resection led to significant increase in villous height, mucosal thickness and PCNA index, which proved that our massive small bowel resection model had induced adaptive hyperplasia in remnant ileum. We chose to study the remnant ileum because previous studies had revealed that after massive small bowel resection the remnant ileum bore greater adaptive potential than the remnant jejunum[14,15]. Moderate dose of rhGH (1 IU·kg-1·day-1) stimulated further hyperplasia of remnant small bowel mucosa, which was manifested by increased villous height, PI value, and PCNA index. C-jun encoded a member of the AP-1 complex of transcription factors that were known to increase after various mitogenic stimuli. Previous studies had demonstrated that enhanced intestinal proliferative activity was associated with augmentation of intestinal expression of C-jun[16,17]. Semi-quantitative analysis of C-jun mRNA revealed enhanced expression of C-jun in GH-resect animals, which further reflected increased proliferative activity.

The result of our study was consistent with the notion that GH is an important growth factor for small intestinal mucosa. Complete GH depletion due to hypophysectomy caused pronounced hypoplasia of small intestinal mucosa with decreased villous height and reduced cryptal cell proliferation. Simple replacement of GH can restore mucosal proliferative activity[18]. Hypophysectomy was shown to impair the adaptive hyperplasia in response to small bowel resection[19]. Study of the transgenic mice overexpressing the bovine growth hormone demonstrated that chronic GH excess could produce hyperplasia in small intestinal mucosa whether food intake was ad lib or restricted[20]. Short-term GH administration has also been shown to promote further hyperplasia of remaining small intestinal mucosa, which was not associated with appetite variation[2].

Plasma IGF-I is primarily derived from liver and GH is the principal stimulus for IGF-I synthesis in liver as well as in peripheral tissues[21]. Apart from GH, nutritional status is another major regulator of plasma IGF-I concentration[22]. Both calorie restriction and protein restriction have been shown to down-regulate the plasma IGF-I level. In this study, massive small bowel resection significantly lowered the plasma IGF-I concen-trations in two bowel-resected groups. This may be attributed to bowel resection-induced impairment of nutrient absorption as the mean body weights of these two groups were significantly decreased. Nevertheless, animals in GH-resect group had higher plasma IGF-I concentrations than those in control-resect group. This suggests that as a powerful stimulatory agent for IGF-I synthesis, GH is still effective in enhancing IGF-I synthesis even in condition of mild nutritional restriction.

GH and IGF-I can both exert marked anabolic effect, stimulate nitrogen accretion, and lean body weight gain even when nutrition supply is restricted mildly or moderately[23]. Therefore, in our experiment, improved body weight gain in GH-resect group could at least partially result from the anabolic effect of GH. On the other hand, GH treatment stimulated the remnant small bowel mucosa hyperplasia and increased the absorptive area of the remnant small bowel in GH-resect group. As adaptive enlargement of absorptive area of remnant small bowel is a major mechanism by which the absorptive capacity of the remnant small bowel can be enhanced[24], it is reasonable to speculate that the nutrient absorption function of animals in GH-resect group was improved by GH treatment. The accelerated body weight gain in GH-resect group therefore is very likely due to the combined effect of increased nutrient absorption and improved anabolic metabolism.

The enterotrophic effect of GH observed in this study may well be mediated by GH-induced enhancement of local IGF-Iproduction within the intestinal mucosa. Convincing evidence has shown that IGF-I is a very important intestinal growth factor. Systemic IGF-I administration increased rat small bowel mass in normal rat[25], in parenterally fed rat[26], in catabolic status induced by dexamethasone[27], in compensatory intestinal mucosa hyperplastic status[9], as well as in post-transplantational status[28].GH transgenic mice have increased expression of endogenous IGF-I locally within small bowel as well as increased plasma concentrations of IGF-I, whereas IGF-I transgenic mice have increased IGF-I serum level, local expression in small bowel, and secondary GH deficiency. However, the effects on small bowel growth are similar in these two transgenics[20,29]. These observations suggest that IGF-I mediates most of the enterotrophic effects of GH. Besides, recent studies on IGF-I null mice have proved definitely that IGF-I is essential for postnatal somatic growth and mammary development in response to GH[30,31]. These discoveries make it very possible that IGF-I mediates the enterotrophic effect of GH. In addition, recent gene targeting study has demonstrated that liver-derived IGF-I is not essential for normal postnatal growth[32]. This discovery gives strong emphasis to the importance of IGF-I locally produced. In support, GH induced high serum IGF-I level is not necessarily associated with enhanced growth of peripheral tissues[33,34]. Therefore, we deduce that IGF-I produced locally within intestinal mucosa mediates the enter otrophic effect of GH.

However, Vanderhoof and his colleagues have published conflicting data, which failed to prove the mitogenic effect of short-term GH administration on rat intestinal mucosa[35,36]. Close examination of the experimental conditions revealed that in one of the two studies continuous subcutaneous infusion of rhGH at a dosage of 3 mg·kg-1·day-1 failed to produce significant change in serum concentrations of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) whether the animals had undergone bowel transection or resection[35]. On the other hand, serum IGF-I and IGFBP-3 both are known to be up-regulated by serum GH concentration[37]. So unaltered serum levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 may be taken as evidence for insufficient action of GH in their experiment. On the contrary, in our experiment rhGH at 1 IU·kg-1·day-1 was sufficient to increase rat plasma IGF concentration in bowel-resected rats. In another study the authors increased the dosage to 12 mg·kg-1·day-1, which produced significant increase in serum IGF concentration. However, they had not observed GH mitogenic action on intestinal mucosa[37]. To interpret these phen-omena, other difference in experimental conditions should be emphasized. First, the control of food-intake, both the presence and quantity of which have been established as important regulators of postransectional small bowel adaptive hyperplasia[38,39]. Vanderhoof et al[9] had employed pair-feeding to distinguish the effect of diet and GH, while our animals were fed ad lib. Though our preliminary observation indicated unremarkable difference in food-intake between the control-resect group and GH-resect group, at present, we cannot decide whether the effect of food-intake on intestinal proliferation in our experiment is involved in the effect of GH administration. Second, the ages of experimental animals were different, we and Shulman et al[2] used adult rats while Vanderhoof et al[9] used young rats. Therefore it is most possible that the responsiveness of intestinal mucosa to GH stimulation is influenced by age. These apparently inconsistent observations indicate the complexity of growth regulation of intestinal mucosa and warrant further studies to explore the influence of age and food intake on the enterotrophic effects of GH.

These findings of our animal experiment certainly cannot be used directly to extrapolate the condition in human beings. However, the possibility that patients with short bowel syndrome may be benefited by the same mechanism from GH administration during the early adaptation stage is of important clinical relevance. After massive small bowel resection, the adaptation of the remnant small bowel usually takes months to 2 years[40,41]. Augmentation or acceleration of the adaptive process means not only less hospital care and expense on parenteral nutrition but also better well-being and life quality.

In summary, we have observed that GH administration stimulates remnant small intestinal mucosa proliferation though whether it is due to direct GH action on intestinal mucosa or due to indirect effect of increased food-intake induced by GH administration has not been clearly determined in this study. Early GH treatment may benefit patients immediately after massive small bowel resection.