Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.116856

Revised: December 7, 2025

Accepted: January 7, 2026

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 81 Days and 16.4 Hours

The special choledocholithiasis (common hepatic duct stone) proximal to hepa

A 58-year-old male with a history of PD for a duodenal tumor eleven years prior presented with a three-month history of intermittent upper abdominal discomfort. Imaging revealed a nodular filling defect in the common hepatic duct and mild in

EUS-TASR is a viable, minimally invasive approach for managing choledocholithiasis in post-PD patients with altered anatomy where conventional endoscopic access is restricted.

Core Tip: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is often anatomically impossible for choledocholithiasis after pancreaticoduodenectomy. This case highlights endoscopic ultrasound-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal as a highly promising minimally invasive solution. By enabling precise puncture and single-session stone removal through a transgastric approach in surgically altered anatomy, endoscopic ultrasound-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal avoids the need for multiple procedures or complex surgery, positioning it as a potential first-line therapy in such patients. Further studies are warranted to standardize this advanced technique.

- Citation: Li YM, Yasen A, Chen SF, Fan J, Huang XB, Zuo GH, Zheng L. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal for choledocholithiasis after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 116856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/116856.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.116856

Choledocholithiasis proximal to the hepaticojejunostomy anastomosis following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a rare but challenging benign biliary complication, often necessitating technically demanding endoscopic interventions or surgical revision of choledochoenterostomy[1,2]. Its pathogenesis involves multifactorial interactions stemming from surgically altered anatomy, with key contributors including hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture, biliary stasis and altered biliary composition, local inflammation, retained foreign material, biliary duct dilation, preexisting biliary stones or chronic cholangitis, excessively long biliary segments or the formation of a pouch-like configuration and impaired ductal vascular supply[3-5].

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) remains the gold standard for managing choledocholithiasis and enables simultaneous diagnosis and therapeutic stone extraction[6,7]. ERCP is typically precluded in post-PD pa

A 58-year-old male with a three-month history of intermittent upper abdominal discomfort presented at our department.

Symptoms began three months prior to presentation with intermittent upper abdominal discomfort.

Eleven years ago, he underwent an open PD at our institution. Postoperative pathological examination revealed a benign duodenal tumor.

His personal history included chronic alcohol consumption (100 mL/day for 40 years) and tobacco use (10 cigarettes/day for 40 years). The patient denied any family history of genetic diseases.

The following vital signs were recorded: Body temperature, 36.3 °C; blood pressure, 110/70 mmHg; heart rate, 78 beats per minute; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute. Physical examination revealed mild tenderness in the upper abdomen.

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 14.96 × 109/L, a neutrophil percentage of 94.8% and a procalcitonin concentration of 3.687 ng/mL. Other indicators, including hepatic function parameters, complete blood count and tumor markers showed no significant abnormalities.

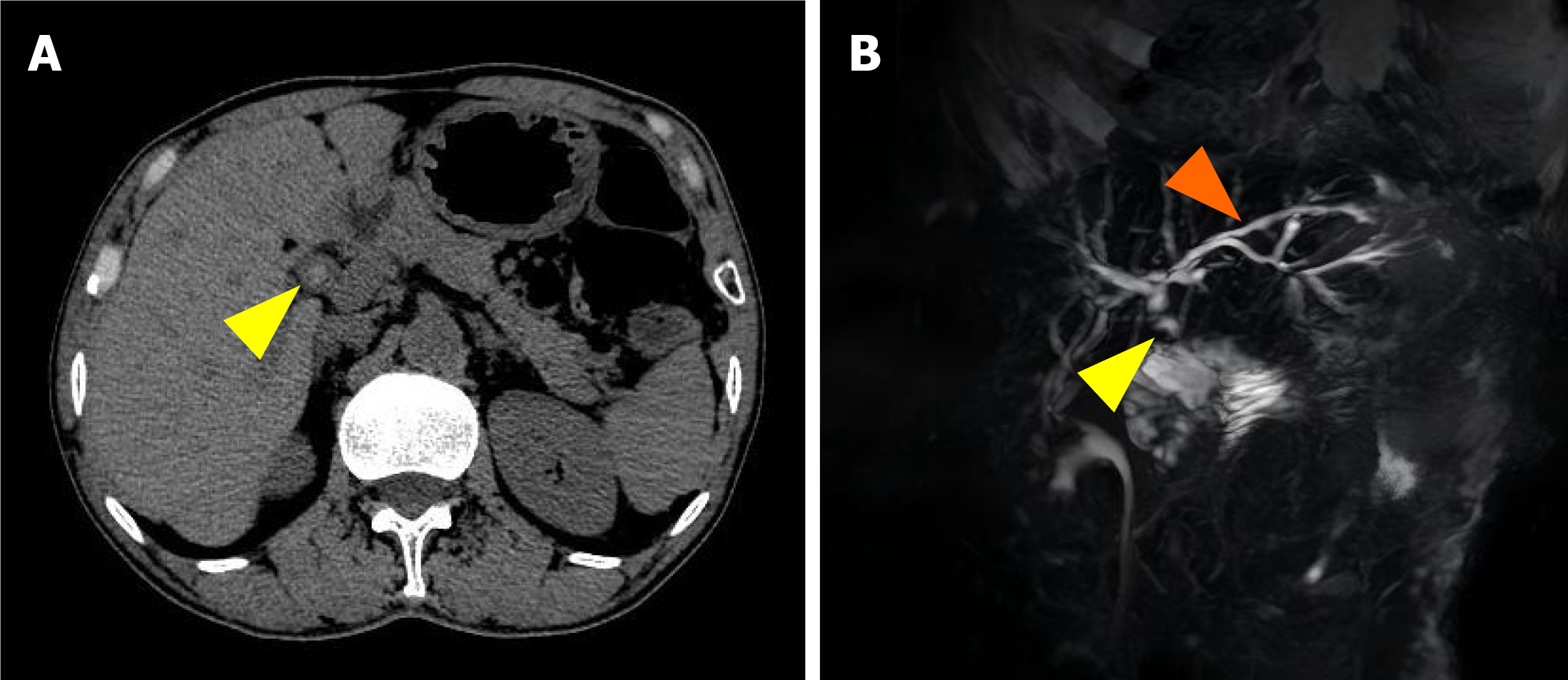

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed hyperdense foci in the common hepatic duct, indicating the presence of calculi (Figure 1A). Subsequent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography confirmed 7-mm filling defects in the common hepatic duct with mild intrahepatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1B).

On the basis of these findings, the diagnosis was symptomatic common hepatic duct stones, warranting consideration of therapeutic endoscopic procedures or surgical intervention.

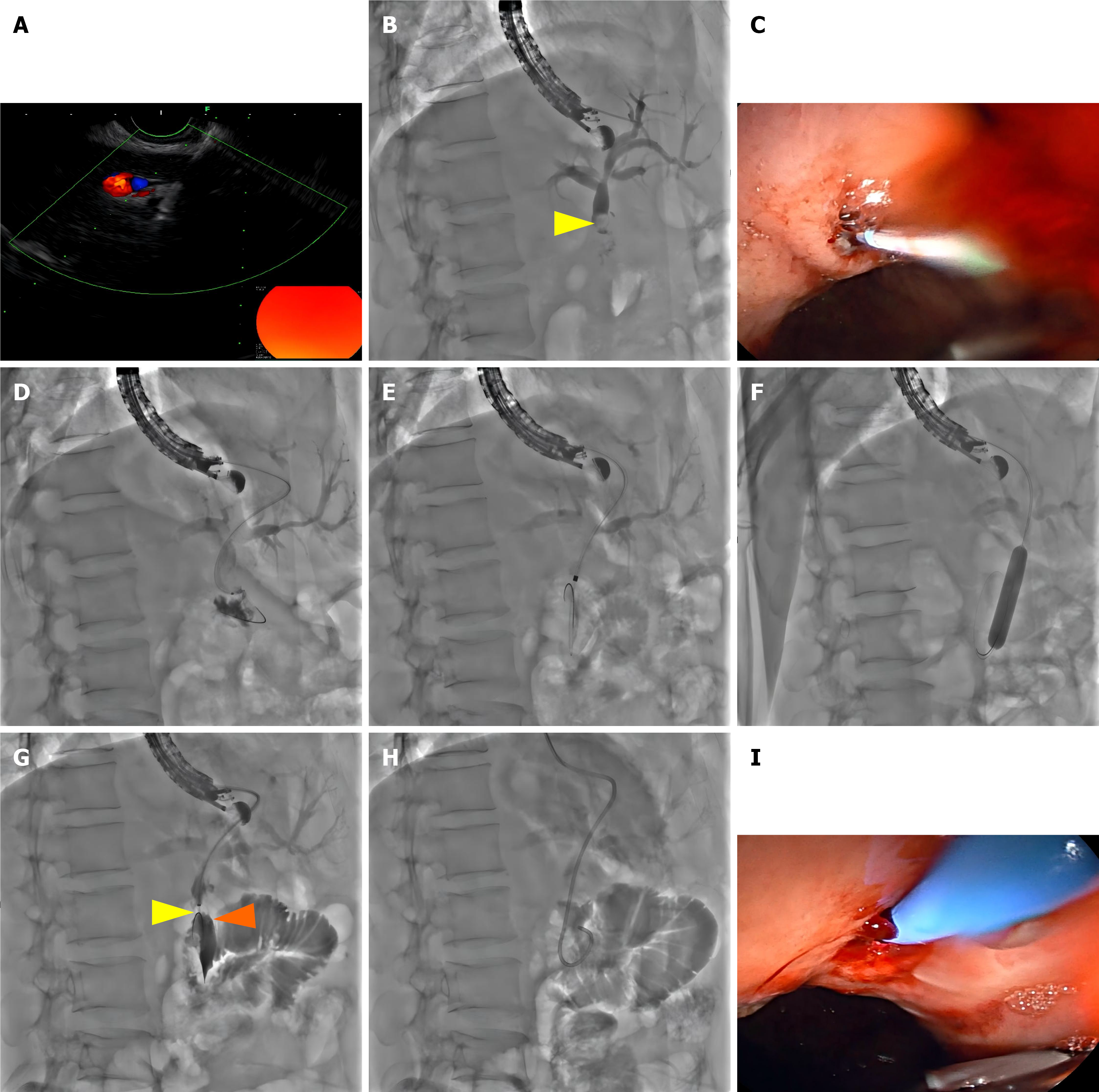

A linear-array scanning echoendoscope (EG-580UT; Fujiflim, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced to the gastric fundus. After confirming the absence of gastric fundus varices and the patency of the gastrointestinal anastomosis, an echoendoscope was used to scan the left lateral lobe of the liver, identifying a mildly dilated bile duct in segment S2 (diameter approximately 2.9 mm). A 19-gauge fine-needle aspiration needle (Boston Scientific, MA, United States) was used to puncture the selected S2 duct branch under EUS guidance, and bile was aspirated (Figure 2A). Cholangiography revealed mildly dilated intrahepatic bile ducts and a 0.7 cm hyperechoic nodule within the common hepatic duct. Notably, the contrast agent did not opacity the distal jejunum (Figure 2B). Subsequently, a 0.035-inch Zebra guidewire with a hydrophilic tip (Boston Scientific, MA, United States) was advanced into the left intrahepatic duct.

After the fine-needle aspiration needle was withdrawn, a triple lumen needle knife (MicroKnife™ XL, 5.5F, Boston Scientific, MA, United States) was used over the guidewire to incise the gastric wall and the liver parenchyma (Figure 2C) to access the left hepatic duct lumen. The guidewire was then advanced across through the biliary-enteric anastomosis into the jejunum under manipulation with a sphincterotome (Figure 2D). The hepatoenteric tract created was dilated using 5-8.5F dilators (Cook Medical, IN, United States) (Figure 2E). The narrow biliary-enteric anastomosis was sequentially dilated by using 6 mm/7 mm/8 mm and 8 mm/9 mm/10 mm balloon dilatation catheters (CRE™ Wireguided, Boston Scientific, MA, United States) (Figure 2F).

The stone within the common hepatic duct was successfully dislodged and pushed into the jejunum loop using a retrieval balloon catheter (9 mm/12 mm; Extractor™ pro XL; Boston Scientific, MA, United States) using repeated withdrawal and advancement maneuvers (Figure 2G). After complete stone removal, repeat cholangiography confirmed the absence of residual stones within the intrahepatic ducts. Finally, an 8.5F nasobiliary drainage catheter (Boston Scientific, MA, United States) was placed across the bilioenteric anastomosis over the guidewire (Figure 2H and I). The echoendoscope was then withdrawn, and the nasobiliary tube was properly secured.

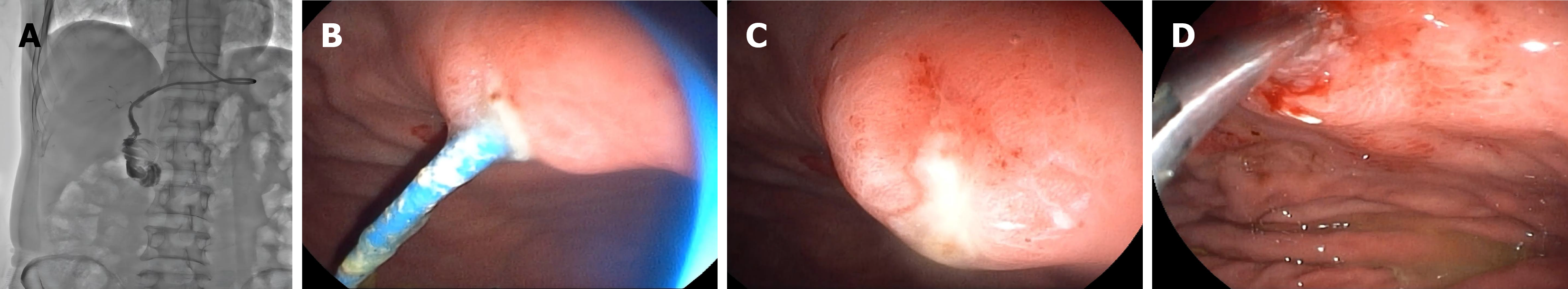

Postoperatively, the patient received a three-day course of cefuroxime for infection prophylaxis, fluid replacement and continuous nasobiliary drainage (approximately 300 mL of bile per day). On postoperative day 7, cholangiography via the nasobiliary duct revealed no residual stones in the intrahepatic bile ducts and no significant stenosis at the biliary-enteric anastomosis site (Figure 3A). Subsequently, a duodenoscope was inserted into the stomach cavity, confirming the proper position of the nasobiliary tube (Figure 3B). The nasobiliary tube was then removed under direct vision, and meticulous endoscopic observation confirmed the absence of active hemorrhage or biliary leakage at the puncture site (Figure 3C). Hemostatic clips were applied to close the puncture site to ensure hemostasis (Figure 3D). The patient was discharged on postoperative day 8.

At the ten-month follow-up after EUS-TSAR, the patient remained free of complications such as upper abdominal discomfort, fever, recurrence of bile duct stones, and jaundice.

Choledocholithiasis following PD is a rare but clinically challenging complication, that occurs in approximately 2%-5% of patients within 5-15 years post-surgery[2]. Its development involves interconnected multifactorial mechanisms. Anastomotic strictures, which occur in 2%-11% of cases, initiate biliary stasis that promotes bacterial colonization and stone formation[11-13]. Biliary-enteric reflux exacerbates this process by facilitating ascending cholangitis and pigment stone deposition[14]. Ischemic injury at the hepaticojejunostomy site contributes significantly, leading to fibrotic scarring and impairing ductal clearance mechanisms[15]. Additionally, excessively long afferent limbs or pouch-like configurations above the anastomosis create sediment traps where debris accumulates[16]. In the present case, the patient exhibited several classic risk factors, including chronic inflammation at the anastomotic site, biliary-enteric anastomotic stricture and ischemic injury at the hepaticojejunostomy site following PD, all of which synergistically promoted stone formation.

The optimal therapeutic strategy for this case was determined by a multidisciplinary team comprising hepatobiliary surgeons, gastroenterologists, experienced endoscopists, diagnostic radiologists and ultrasound interventionalists. Surgical treatment for choledocholithiasis after PD, traditionally considered the traditional standard, is associated with significant trauma, slow recovery, and prolonged hospitalization. ERCP success rates are relatively low because of excessively long afferent limbs, dense adhesions preventing the duodenoscope from reaching the biliary anastomosis, and difficulty in identifying the narrow biliary-enteric anastomosis post-PD. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotripsy (PTCSL) requires sufficiently dilated intrahepatic bile ducts, repeated sinus tract dilation, and the insertion of a bile drainage tube, which can cause patient discomfort and bile leakage. Consequently, after comprehensive discussion, a EUS-guided intervention was considered an efficient solution for such anatomically complex scenarios. Specifically, EUS-TASR offers a minimally invasive, single-session therapeutic option with the advantages of minimal trauma, rapid recovery and low cost.

The successful implementation of EUS-TASR in this case demonstrated several innovative techniques. First, successful transgastric puncture of the mildly dilated left intrahepatic duct (segment II, 2.9 mm) was crucial and depended on exquisite puncture skills to precisely avoid the hepatic artery and portal vein branches, providing stable access and direct alignment with the stonebearing the common hepatic duct. Second, a meticulous dilation strategy involving gradual tract dilation (5F-8.5F) followed by sequential balloon dilation for biliary-enteric anastomosis (6-8 mm, then 8-10 mm) was employed to minimize ductal trauma. Third, for stone extraction, a 9-12 mm retrieval balloon enabled antegrade dislodgement and propulsion into the jejunum without lithotripsy, reducing procedural time and complexity. Finally, prophylactic nasobiliary tube placement across the anastomosis reduces the risks of postoperative bleeding, bile leakage, and biliary tract infection. Moreover, postoperative cholangiography via the nasobiliary tube confirmed the absence of residual stones and revealed the patency of the biliary-enteric anastomosis. A double pigtail stent was not placed because of the potential risks of stone recurrence, stent displacement, and the need for subsequent hospitalization for stent removal.

Post-PD choledocholithiasis can be managed using several approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Conventional ERCP, although effective for normal anatomy, is often anatomically inaccessible after PD, resulting in low success rates (< 20%) and notable complication risks (10%-25%), such as perforation and pancreatitis[17-19]. PTCSL, although feasible, typically requires multiple sessions, imposes the burden of an external drain, and has risks of bleeding and infection (10%-30% complication rate)[20,21]. Surgical revision, although highly effective (> 90% success), is as

| Method | Success rate | Major limitations | Complication rate | Ref. |

| ERCP | < 20% | Anatomical inaccessibility, long Roux limbs, adhesions | 10%-25% (perforation, pancreatitis) | [17-19] |

| PTCSL | 70%-88% | External drain burden, fistula risk, requires multiple sessions | 10%-30% (bleeding, infection) | [20,21] |

| Surgical revision | > 90% | High morbidity/mortality (5%-15%), challenging reoperation | 5%-20% (anastomotic leak, recurrent stricture) | [22,23] |

| EUS-TASR | 85%-95% | Requires advanced expertise, limited right-duct access | 8%-15% (bleeding, bile leak) | [24,25] |

Despite its promising results, EUS-TASR has several limitations. Primarily, the procedure demands exceptional te

In conclusion, EUS-TASR is a highly promising approach for managing choledocholithiasis in the context of surgically altered anatomy. By enabling transgastric access and facilitating antegrade instrumentation, EUS-TASR effectively cir

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the patient and his family for their support.

| 1. | Ito T, Sugiura T, Okamura Y, Yamamoto Y, Ashida R, Aramaki T, Endo M, Matsubayashi H, Ishiwatari H, Uesaka K. Late benign biliary complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2018;163:1295-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Nagai M, Nakagawa K, Nishiwada S, Terai T, Hokuto D, Yasuda S, Matsuo Y, Doi S, Akahori T, Sho M. Clinically Relevant Late-Onset Biliary Complications After Pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2022;46:1465-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, Wang WM, Wan YL, Huang YT. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2456-2461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | House MG, Cameron JL, Schulick RD, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ. Incidence and outcome of biliary strictures after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;243:571-6; discussion 576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mie T, Sasaki T, Kobayashi K, Takeda T, Okamoto T, Kasuga A, Inoue Y, Takahashi Y, Saiura A, Sasahira N. Impact of preoperative self-expandable metal stent on benign hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture after pancreaticoduodenectomy. DEN Open. 2024;4:e307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shah-Khan SM, Zhao E, Tyberg A, Sarkar S, Shahid HM, Duarte-Chavez R, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Directed Transgastric ERCP (EDGE) Utilization of Trends Among Interventional Endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:1167-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ichkhanian Y, Yang J, James TW, Baron TH, Irani S, Nasr J, Sharaiha RZ, Law R, Wannhoff A, Khashab MA. EUS-directed transenteric ERCP in non-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgical anatomy patients (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:1188-1194.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Srivastava RP, Moran RA, Elmunzer BJ. EUS-guided enteroenterostomy to facilitate peroral altered anatomy ERCP. VideoGIE. 2024;9:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brenner TA, Bapaye J, Zhang L, Khashab M. EUS-directed transenteric ERCP-assisted internalization of a percutaneous biliary drain in Roux-en-Y anatomy. VideoGIE. 2022;7:364-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brewer Gutierrez OI, Runge T, Ichkhanian Y, Vosoughi K, Khashab MA. Lumen-apposing metal stent for the creation of an endoscopic duodenojejunostomy to facilitate bile duct clearance following Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 2019;51:E400-E401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Javed AA, Mirza MB, Sham JG, Ali DM, Jones GF 4th, Sanjeevi S, Burkhart RA, Cameron JL, Weiss MJ, Wolfgang CL, He J. Postoperative biliary anastomotic strictures after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2021;23:1716-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morgan KA, Fontenot BB, Harvey NR, Adams DB. Revision of anastomotic stenosis after pancreatic head resection for chronic pancreatitis: is it futile? HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matsumoto I, Kamei K, Kawaguchi K, Yoshida Y, Matsumoto M, Lee D, Murase T, Satoi S, Takebe A, Takeyama Y. Longitudinal Pancreaticojejunostomy for Pancreaticodigestive Tract Anastomotic Stricture After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2022;6:412-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim JK, Park CH, Huh JH, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung J, Bang S. Endoscopic management of afferent loop syndrome after a pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenecotomy presenting with obstructive jaundice and ascending cholangitis. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bannone E, Andrianello S, Marchegiani G, Malleo G, Paiella S, Salvia R, Bassi C. Postoperative hyperamylasemia (POH) and acute pancreatitis after pancreatoduodenectomy (POAP): State of the art and systematic review. Surgery. 2021;169:377-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Choquet A, Sokal A, Dokmak S, Le Bot A, Delahaye F, Dembinski J, Aussilhou B, Rebours V, de Lastours V, Sauvanet A. Recurrent Nonobstructive Cholangitis After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Treatment. World J Surg. 2025;49:2570-2577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Garcés-Durán R, Monino L, Deprez PH, Piessevaux H, Moreels TG. Endoscopic treatment of biliopancreatic pathology in patients with Whipple's pancreaticoduodenectomy surgical variants: Lessons learned from single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2024;23:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamauchi H, Kida M, Imaizumi H, Okuwaki K, Miyazawa S, Iwai T, Koizumi W. Innovations and techniques for balloon-enteroscope-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6460-6469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Katanuma A, Isayama H. Current status of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with surgically altered anatomy in Japan: questionnaire survey and important discussion points at Endoscopic Forum Japan 2013. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Piraka C, Shah RJ, Awadallah NS, Langer DA, Chen YK. Transpapillary cholangioscopy-directed lithotripsy in patients with difficult bile duct stones. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1333-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Verdonk RC, de Ruiter AJ, Weersma RK. [Treatment of complex biliary stones by cholangioscopy laser lithotripsy in 10 patients]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A2085. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Testini M, Piccinni G, Lissidini G, Gurrado A, Tedeschi M, Franco IF, Di Meo G, Pasculli A, De Luca GM, Ribezzi M, Falconi M. Surgical management of the pancreatic stump following pancreato-duodenectomy. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Duconseil P, Turrini O, Ewald J, Berdah SV, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Biliary complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: skinny bile ducts are surgeons' enemies. World J Surg. 2014;38:2946-2951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yu T, Hou S, Du H, Zhang W, Tian J, Hou Y, Yao J, Hou S, Zhang L. Simplified single-session EUS-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal for management of choledocholithiasis in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2024;12:goae056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mukai S, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka R, Tonozuka R, Honjo M, Fujita M, Yamamoto K, Nagakawa Y. EUS-guided antegrade intervention for benign biliary diseases in patients with surgically altered anatomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:399-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Iwashita T, Iwasa Y, Senju A, Tezuka R, Uemura S, Okuno M, Iwata K, Mukai T, Yasuda I, Shimizu M. Comparing endoscopic ultrasound-guided antegrade treatment and balloon endoscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of bile duct stones in patients with surgically altered anatomy: A retrospective cohort study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:1078-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Iwashita T, Nakai Y, Hara K, Isayama H, Itoi T, Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided antegrade treatment of bile duct stone in patients with surgically altered anatomy: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nakai Y, Kogure H, Isayama H, Koike K. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage for Benign Biliary Diseases. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pizzicannella M, Caillol F, Pesenti C, Bories E, Ratone JP, Giovannini M. EUS-guided biliary drainage for the management of benign biliary strictures in patients with altered anatomy: A single-center experience. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Bronswijk M, Tyberg A, Vanella G, Anderloni A, Hindryckx P, Shahid H, Arcidiacono PG, Ratone JP, Sarkar A, Binda C, Andalib I, Laleman W, Poley JW, Haba MG, Caillol F, Fabbri C, Boeken T, Becq A, Monino L, Cellier C, Kahaleh M, van der Merwe S. Transenteric ERCP via EUS-guided anastomosis using lumen-apposing metal stents in patients with surgically altered anatomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;S0016-5107(25)02080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dietrich CF, Braden B, Burmeister S, Aabakken L, Arciadacono PG, Bhutani MS, Götzberger M, Healey AJ, Hocke M, Hollerbach S, Ignee A, Jenssen C, Jürgensen C, Larghi A, Moeller K, Napoléon B, Rimbas M, Săftoiu A, Sun S, Bun Teoh AY, Vanella G, Fusaroli P, Carrara S, Will U, Dong Y, Burmester E. How to perform EUS-guided biliary drainage. Endosc Ultrasound. 2022;11:342-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/