Published online Feb 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113693

Revised: October 31, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: February 7, 2026

Processing time: 149 Days and 20.5 Hours

Accurate prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recurrence after curative therapy remains challenging. Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2

To evaluate the association between preoperative M2BPGi levels and HCC recu

We searched PubMed Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, and BIOSIS Citation Index for English-language studies in humans reporting HCC recurrence outcomes str

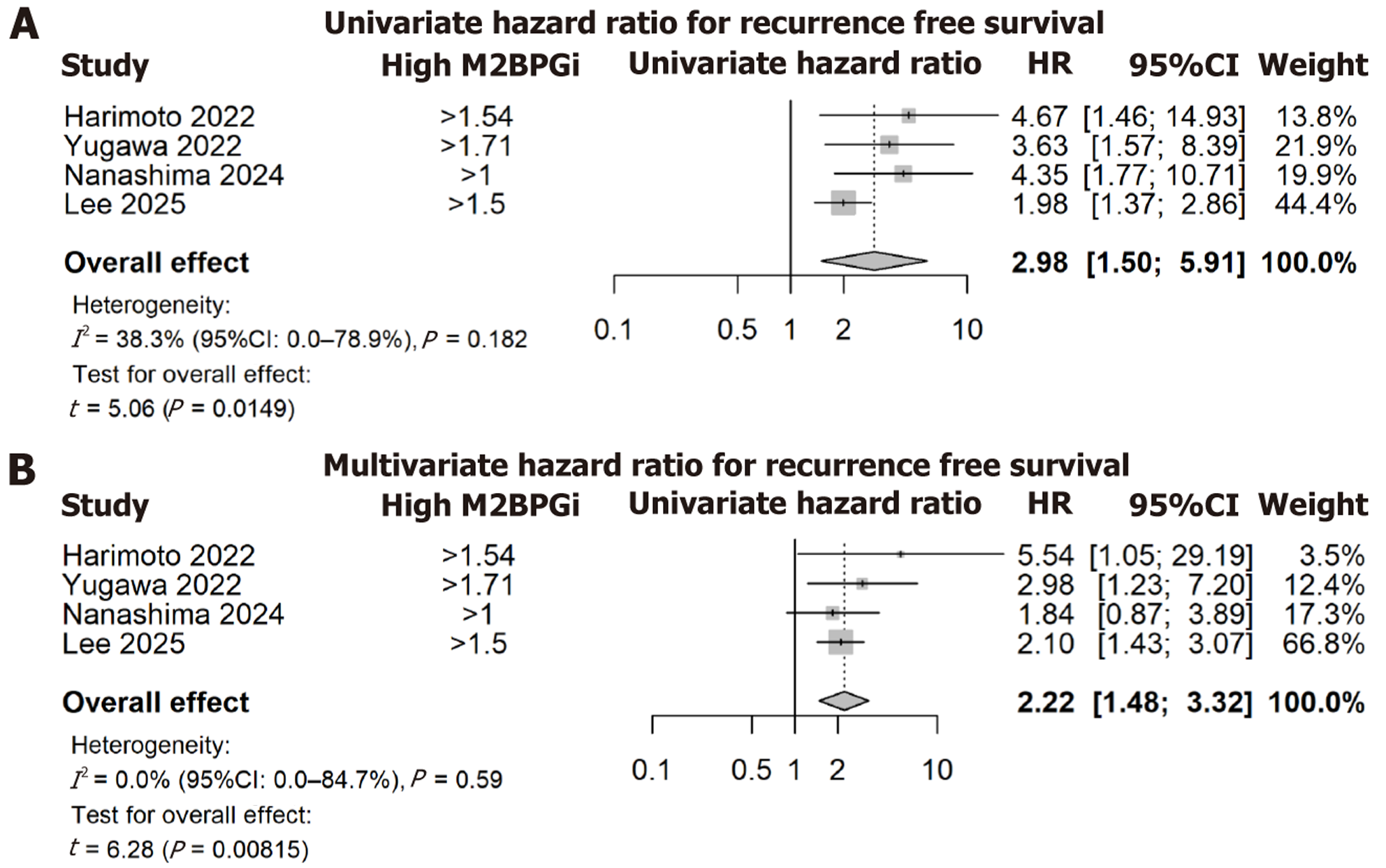

High preoperative M2BPGi was significantly associated with increased recurrence risk. The pooled unadjusted HR was 2.98 (95%CI: 1.50-5.91; P < 0.01; I2 = 38.3%), and the pooled adjusted HR was 2.22 (95%CI: 1.48-3.32; P < 0.01; I2 = 0%). Meta-regression showed no effect of varying cutoff thresholds on HRs, and Egger’s tests indicated no evidence of publication bias in the multivariate results. The bias-corrected estimated of the univariate HR remained statistically significant (HR = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.21-4.41, P = 0.021, I2 = 32%).

Preoperative serum M2BPGi is a promising biomarker for HCC recurrence after hepatectomy. Its strong association with risk, minimal heterogeneity across studies, and ease of measurement support its potential clinical utility.

Core Tip: Predicting tumor recurrence following curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a cha

- Citation: Stephens KR, Wilson M, Xu M, Gaskins JT, Genova G, Martin II RCG. Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer as a novel serum biomarker for recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(5): 113693

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i5/113693.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i5.113693

Primary liver cancer is currently the 6th most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States, with a 5-year survival rate of 22.0%[1]. More recent data shows that alcohol-related and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) make up a greater proportion of HCC in the United States, while viral-related HCC is decreasing due to universal hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination in the United States and sustained viral response (SVR) from hepatitis C virus (HCV) direct acting anti-virals (DAAs)[2]. However, HBV infection remains the most common risk factor associated with HCC on the global scale, being the predominate cause of the cancer in the most high-risk HCC regions (i.e., China, South Korea, and sub-Saharan Africa)[3,4]. Regardless of the underlying etiology, the development of cirrhosis is the most commonly exhibited risk factor in HCC and is present in 80% of cases[5].

Treatment for HCC depends on disease staging. Approximately 30%-40% of patients are diagnosed at earlier stages [Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stages 0 and A or American Joint Committee on Cancer stages IA-B]. These cases are usually treated with curative intent, namely partial hepatectomy, liver transplantation, or microwave ablation[3,6]. Due to the high risk of HCC recurrence in the curative intent modalities, surveillance following treatment is recom

In addition, the use of serum biomarkers has been of great interest to clinicians due to their potential ability to provide valuable information about HCC prognosis and recurrence. Historically, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) has been utilized as both a biomarker of diagnosis (with levels > 400 ng/mL being considered diagnostic) and of recurrence in AFP-positive patients, used in adjunct with serial imaging[5]. However, greater than 40% of HCC tumors have been found to be AFP-negative, and AFP production is not specific to HCC, with other tumors such as those of germ cell origin and hepatoblastoma also secreting the biomarker[5,7]. In a large Italian multi-center review of 1158 patients, 18% had AFP > 400 and 46% had normal AFP (< 20) at diagnosis[8]. Though still routinely used in diagnosis and surveillance of HCC, these factors limit AFP’s ability to reliably predict HCC recurrence and behavior. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines also acknowledge des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), also known as protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, and lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP (AFP-L3), an isoform of AFP, as additional biomarkers that are useful for additional risk stratification, but does not routinely recommend their use for surveillance status post curative intent therapy[9]. Thus, there is a need for novel serum biomarkers that can more accurately predict pro

Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2BPGi) is a glycoprotein previously shown to be a biomarker of liver fibrosis, with the unaltered Mac-2 binding protein undergoing changes in N-glycosylation to produce M2BPGi as fibrosis progresses[10]. Thus far, this biomarker has been used to diagnose and assess the degree of fibrosis in both chronic viral hepatitis and non-viral liver disease patients, being superior to other non-invasive diagnostic methods overall and dem

In recent years, there has been increased investigation into other possible applications for M2BPGi. Given that cirrhosis is this most significant risk factor for development of HCC, in 80% of cases as previously mentioned, intuitively one could postulate that increasing concentrations of M2BPGi would correlate with an increased risk of HCC recurrence and act as a surrogate biomarker for this process. Thus, given its utility in assessing liver fibrosis and the need for non-invasive biomarkers to predict HCC recurrence, M2BPGi has emerged as a potential biomarker for just that. Furthermore, prior in vitro work has demonstrated that M2BPGi stimulates HCC progression through the mTOR pathway[13]. Here, we perform the first meta-analysis in the literature evaluating M2BPGi as a biomarker of HCC recurrence following curative intent hepatectomy.

M2BPGi was first identified by our group as a novel biomarker after performing a literature review for all possible serum biomarkers for recurrence in HCC following curative intent treatment. English articles in humans between 2020 and 2025 were evaluated in the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, and BIOSIS Citation Index. Of all 1303 studies were identified, there were 1007 studies after duplicates were removed, 235 were identified for full text review following abstract/title screening, and 89 studies met the aforementioned parameters. Biomarkers analyzed in these 89 studies included DCP, circulating tumor cells (CTC), ctDNA, AFP-L3, and M2BPGi. In addition, other included biomarkers consisted of a combination of other serum values, such as albumin-bilirubin grade (ALBI grade), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR).

While several potential biomarkers were identified in our initial search, many had limited utility in the context of our proposed meta-analysis. For DCP, AFP-L3, and ALBI, there have already been other meta-analyses examining their role in HCC behavior and recurrence. While CTCs and ctDNA demonstrate promising data in predicting recurrence, we found that the included studies contained much variability in wet lab technique, making direct statistical comparison between them difficult. The remainder of the biomarkers contained too few studies to perform an adequate meta-analysis. The sole biomarker in our initial search that had a sufficient number of comparable studies and had not already been analyzed within a meta-analysis was M2BPGi. At that time, we identified 4 studies that involved M2BPGi, which was a considered a novel assay and had not previously undergone this level of analysis. Therefore, the following sys

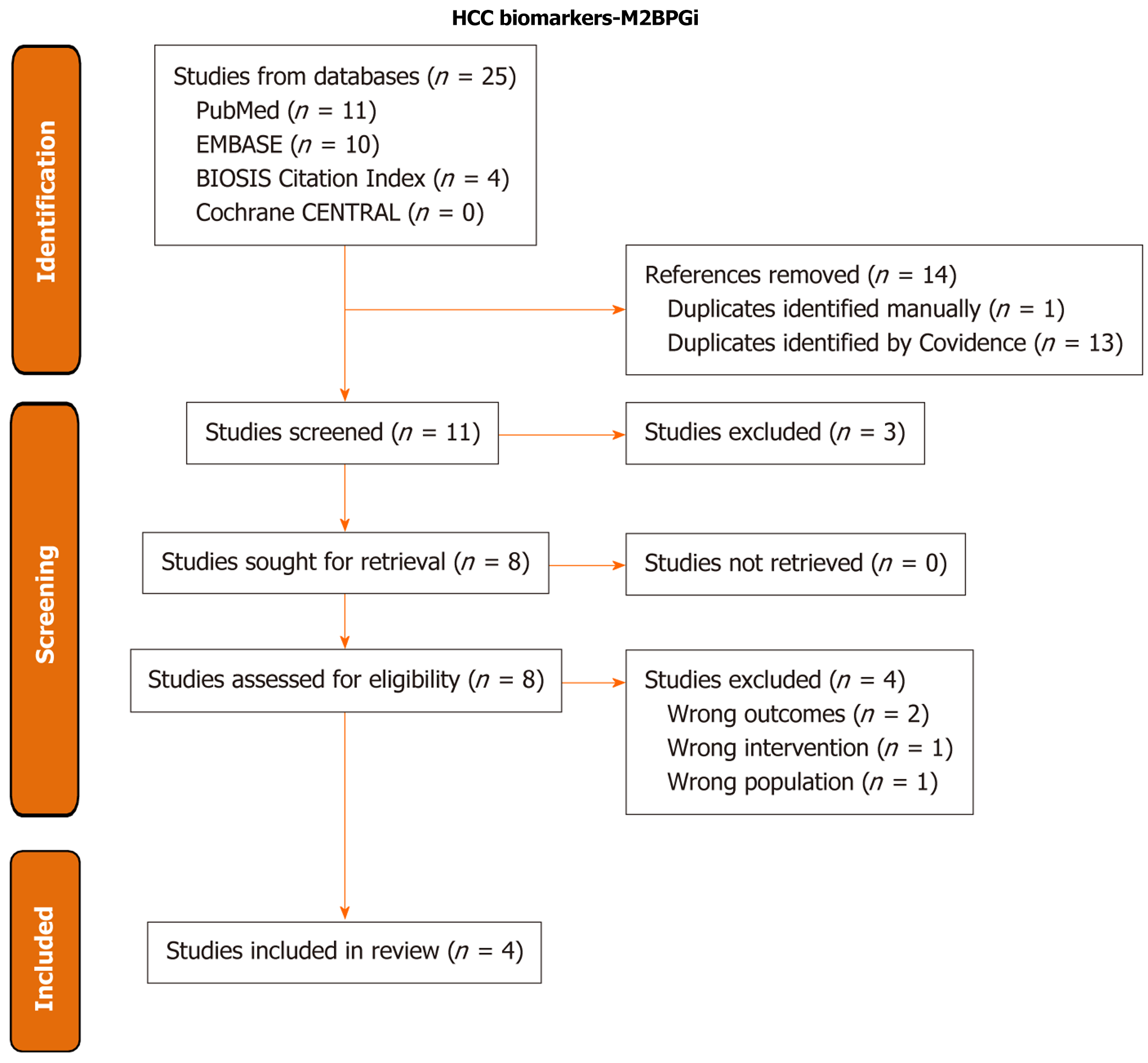

We then conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis for studies on the use of M2BPGi as a biomarker for HCC recurrence. Databases searched included PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, and BIOSIS Citation Index. The PubMed search strategy was: (“Carcinoma, Hepatocellular”[Mesh] OR “hepatocellular carcinoma”[tiab] OR “hepatocellular cancer*”[tiab] HCC[tiab] OR “liver carcinoma*”[tiab] OR “liver cancer*”[tiab] OR “liver tumor*”[tiab] OR “liver tumour*”[tiab] OR “liver neoplas*”[tiab] OR “liver malignan*”[tiab] OR “hepatic carcinoma*”[tiab] OR “hepatic cancer*”[tiab] OR “hepatic tumor*”[tiab] OR “hepatic tumour*”[tiab] OR “hepatic neoplas*”[tiab] OR “hepatic malignan*”[tiab]) AND (M2BPGi*[tiab] OR “mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer*”[tiab] OR “mac-2 binding protein glycan isomer*”[tiab] AND (Recurrence[Mesh] OR recur*[tiab]). Search results were filtered to English. Full search strategies for all databases are available in the Supplementary material. Covidence was used to complete screening and to generate the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia)[14]. Two independent reviewers performed title/abstract screening and full-text review, and conflicts were resolved by the lead author.

Inclusion criteria was as follows: (1) Patients were diagnosed with HCC; (2) Serum M2BPGi was obtained; (3) Patients underwent curative treatment; (4) Recurrence data was collected follow treatment; and (5) Published in peer-reviewed journal articles. Two independent reviewers were utilized for data extraction, and the lead author resolved any conflicts. Major variables collected during extraction include study design, sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria, demographic distribution of the cohort (including age, gender, HCC BCLC/tumor-node-metastasis stage, underlying liver disease, treatment type, and follow-up duration), and recurrence definition. Recurrence metrics extracted include recurrence free survival (RFS) and tumor free survival (TFS). Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies was utilized to evaluate for risk of bias.

The included studies provided comparisons of a recurrence-related survival measure and a high/Low binary categorization of M2BPGi. We used both univariate (unadjusted) and multivariate (adjusted) hazard ratios (HR) on all. One study, Nanashima et al[15], reported RFS as TFS in 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals, so this data was converted into an approximate unadjusted HR using the methods described by Tierney et al[16].

HRs are summarized across manuscripts using random effects meta-analysis on the log-HR, unadjusted and adjusted analyzed separately. We used a random effect model to account for expected heterogeneity across publications and report heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. Publication bias was assessed using Egger test for funnel plot asymmetry; the Duval & Tweedie trim and fill method was used to re-estimate the pooled effect in cases when publication bias was detected[17]. Significant differences in the HR based on the different values of the threshold chosen to define high levels of M2BPGi were also tested by fitting a meta-regression model with threshold value as the predictor. All analyses were run in R statistical software version 4.2.2[18].

The database searches returned 25 results, with 11 studies remaining from initial screening after de-duplication. Three studies were excluded during title/abstract screening for failing to meet the inclusion criteria, and an additional 4 studies were excluded in full text review, one for lacking recurrence data, one for evaluating HCV patients with SVR following interferon administration, one for containing early recurrence data only, and the final for including the non-curative TACE intervention. The remaining 4 studies were included in the systemic review and meta-analysis. All 4 studies had low risk of bias on the NOS scale, all with 9/9 stars.

The major characteristics of each study are displayed in Table 1. All were retrospective studies, with Harimoto et al[19] being a 2-institution study while the remainder were single-center. Each study originated from different institutions, with no study demonstrating institutional overlap with another. In terms of underlying liver disease, HCV-related HCC was present in all studies, with Nanashima et al[15] and Lee et al[20] including patients with additional etiologies. Hepa

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Country | Underlying liver disease | Treatment type | Serum assay | 1M2BPGi cutoff | Endpoint | Outcome |

| Harimoto et al[19], 2022 | Two institution retrospective study | 60 | Japan | HCV-related HCC at SVR | Hepatectomy | Not specified | 1.54 | RFS | RFS M2BPGi > 1.54. Univariate: HR = 4.67 (1.46-14.92), P < 0.01. Multivariate: HR = 5.54 (1.05-29.14), P = 0.04. Median RFS: High M2BPGi: 1.25 years. Low M2BPGi: Did not reach 50% in 4 years |

| Yugawa et al[24], 2022 | Single-center retrospective study | 57 | Japan | HCV-related HCC at SVR | Hepatectomy | Lectin-antibody Sandwich Immunoassay (Sysmex Co., Hyogo, Japan) | 1.71 COI | RFS | RFS M2BPGi at SVR ≥1.71 COI. Univariate: HR = 3.63 (1.57-8.39), P = 0.0026. Multivariate: HR = 2.98 (1.23-7.19), P = 0.0153. 3/5/7-year RFS: High M2BPGi: 37.3%/12.4%/12.4%. Low M2BPGi: 84.2/84.2%/71.7% |

| Nanashima et al[15], 2024 | Single-center retrospective study | 130 | Japan | HCC with underlying: Normal liver: 30. MASLD: 44. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2. HBV: 30. HCV: 24 | Hepatectomy | Chemiluminescent Enzyme Immunoassay with Anti-Wisteria Floribunda Agglutinin (HSCL-2000i Immunoanalyzer; Sysmex Co., Tokyo, Japan) | 1 COI | TFS | TFS 1/3/5 years: < 1 (n = 75) 91/73/65. ≥ 1 (n = 55) 81/66/53. Multi-variate analysis. M2BPGi (COI) (< 1 vs ≥ 1): TFS RR = 1.84 (0.87-3.89), P = 0.11 |

| Lee et al[20], 2025 | Single-center retrospective study | 247 | Taiwan | HCC with underlying: HBV: 107. HCV: 62. HBV + HCV: 3. Nonviral: 75 | Hepatectomy | HISCL M2BPGi reagent on HISCL-800 immunoanalyzer (Sysmex Co., Kobe, Japan) | 1.5 COI | RFS | RFS M2BPGi (COI). > 1.5 vs ≤ 1.5. Univariate: HR = 1.979 (1.369-2.862), P < 0.001. Multivariate: HR = 2.100 (1.435-3.074), P < 0.001. Median RFS: High M2BPGi: 19.8 months. Low M2BPGi: 56.3 months |

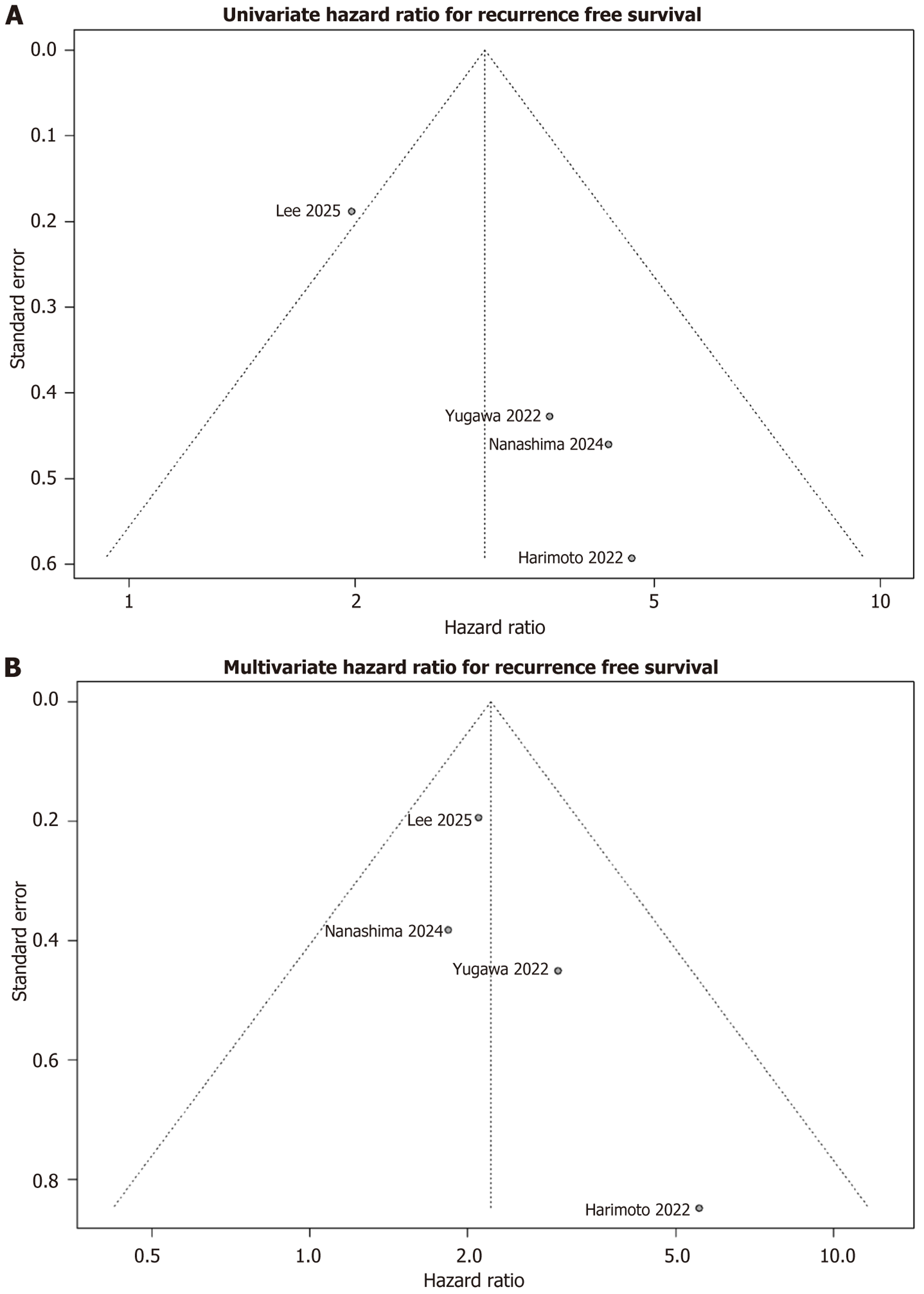

The pooled unadjusted HR was 2.98 (95%CI: 1.50-5.91, P < 0.01), representing a significant association between high M2BPGi and an increased hazard of recurrence events, Figure 2A. Level of heterogeneity across included studies was moderate (I2 = 38.3%). A meta-regression analysis of the M2BPGi cut-off was performed, with no significant association between HRs and the M2BPGi threshold definition (P = 0.71). For the univariate analyses, there was evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (Figure 3A) and significant evidence of publication bias using Egger’s test (P = 0.012). The bias-corrected estimate of the univariate HR again demonstrated a significant association between high M2BPGi and recurrence events (pooled HR = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.21-4.41, P = 0.021).

The overall adjusted HR was 2.22 (95%CI: 1.48 to 3.32, P = 0.008), again representing a significant association between high M2BPGi and increased hazard of recurrence, Figure 2B. Minimal heterogeneity was found across studies (I2 = 0%). The meta-regression analysis again demonstrated no significant association between HRs and the M2BPGi threshold definition (P = 0.46). Using the funnel plot and Egger’s test, there was no evidence of publication bias or asymmetry (P = 0.25), Figure 3B.

After evaluating the 4 studies included in our meta-analysis, we found a significant association between high M2BPGi and elevated risk of HCC recurrence in both our unadjusted and adjusted HR, with HR = 2.98 and HR = 2.22, respectively. Analyses for both publication bias and bias due to difference in M2BPGi threshold definition showed no significant bias in the multivariate analysis. While there was evidence of publication bias for univariate associations, the re-estimated effect continued to show a strong positive association between high M2BPGi and recurrence (HR = 2.31). In both sets of analyses, we found low heterogeneity that would limit comparison between studies. Taken together, this would suggest that pre-operative serum M2BPGi levels, which was not temporally defined across the included studies in terms of when the blood draw was performed, is a promising prognostic indicator for HCC recurrence following curative treatment.

There a several key factors to explore in our analysis. To begin, the included studies observed populations in East Asia, namely Japan and Taiwan. We must keep this in mind when assessing the applicability of our findings to populations of different ethnicities and nationalities. Beyond this, the etiology of HCC can vary by region and should be noted when evaluating HCC behavior and prognosis. HBV, followed by HCV, are the most common causes of HCC in Taiwan, though the country does have a larger HCV-related HCC minority than other HBV-dominate East Asian nations such as South Korea and China[21,22]. These national trends in etiology appear in our included study population as well, with an HBV-related HCC majority being noted in Lee et al[20] in a Taiwanese population. In Japan, however, HCV infection is a more common cause of HCC than HBV[23]. Two of the included Japanese studies (Harimoto et al[19] and Yugawa et al[24]) exclusively observed HCV-related HCC populations, while Nanashima et al[15] included a wider array of both viral and non-viral HCC cases. Because of this, viral-related HCC cases make up a large portion of the overall meta-analysis population (n = 343), though non-viral cases do make up a notable minority (n = 151). The large proportion of both HCV and HBV patients included in our analysis does aid in the applicability of our findings to other populations where either HBV or HCV are the dominant HCC etiology, such as China and the United States, respectively[3,25].

Additionally, HCC etiology merits close examination as past studies have shown that M2BPGi has greatest efficacy when assessing liver fibrosis incurred by active HCV infection vs HBV or non-viral causes[11,12]. However, the adjusted HR shows a strong correlation between high M2BPGi and HCC recurrence, suggesting that serum M2BPGi may also be predictive of HCC prognosis in non-HCV cases. This comes with the caveat that our analysis contains a smaller population of non-viral HCC cases, which is further subdivided into more specific etiologies. Because of this, we must be cautious as these small sample sizes may limit our analysis’ power in these subgroups. As HBV-vaccination rates and HCV eradication via DAAs have increased worldwide, the proportion of non-viral HCC has also risen, with NASH becoming an increasingly prevalent etiology in Western countries[2,23,25]. Thus, there is a need for special attention to ensure any novel biomarkers are also effective in these populations. Nonetheless, the strong association demonstrated by our meta-analysis does implicate M2BPGi as a promising biomarker of recurrence despite our analysis’ relatively lower power in non-viral cases.

Additionally, it is worth noting that several of the studies excluded from our analysis also demonstrated that elevated M2BPGi is predictive of HCC recurrence. Though excluded for a non-curative intervention, the Tak et al[26] study demonstrated that M2BPGi is a significant predictor of recurrence following TACE. However, additional studies would need to be done evaluating M2BPGi in the setting of chemo/radio-embolization or ablation to determine if this novel biomarker has external validity for detecting recurrence following these treatments. One 2022 WJH study by Nakai et al[27] did demonstrate significantly worse RFS among HCV negative patients following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) who had elevated M2BPGi when compared to the low cohort, as demonstrated by the statistically significant relationship between these factors in the studies time-to-event curves. This study had to be excluded from our full analysis due to the authors only reporting time-to-event data without any HR for recurrence, only providing HR for survival in the multi

This study has limitations that must be discussed. First, M2BPGi is fairly new to the commercial market, only used in Asia, and has not been validated in the United States. Thus, there is some inherent limitations in the generalizability of these studies as the population in the United States fits a different demographic and the underlying pathophysiology for developing HCC is often different. Further studies would be required to assess the applicability of M2BPGi in HCC recurrence in Western populations, as current studies demonstrate a notable geographic bias. As mentioned previously, the most prevalent etiology of HCC in the included studies is viral hepatitis, and though non-viral etiologies such as NASH-driven HCC are included in the overall analysis, their overall contribution to the recurrence data is smaller and carries less analytical power. As NASH and NASH-driven HCC rates rise worldwide (and are particularly significant in Western nations such as the United States), further studies into M2BPGi’s prognostic value in HCC recurrence in these populations should be done to address this gap in the data. Additionally, only one company, Sysmex, is commercially offering this assay and corresponding analyzer. Our study only included 4 manuscripts, which may reduce the reliability of our tests for publication bias. Furthermore, the primary intervention of all the studies was hepatectomy. Thus, our results may not be applicable to other treatments, such as liver transplantation or RFA. Finally, we looked at only studies with patients who underwent therapies of curative intent. Neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy were not included, so the impact they have on M2BPGi is not explored here.

M2BPGi is an established, commercially available serum analyte currently utilized by gastroenterologists in Asia for evaluating liver fibrosis. Our analysis has shown that preoperative serum M2BPGi is a promising prognostic biomarker of HCC recurrence that can be easily utilized by medical and surgical oncologists now, but requires send out testing or access to proprietary technology. The strength of its association with recurrence in HBV and particularly HCV-related HCC populations suggest that it may have use in the United States, as well as other regions beyond where our meta-analysis’s component studies occurred. Further investigations into its efficacy in different HCC etiologies and treatment types will allow for a better definition of its strengths, weaknesses, and the role it can play in HCC treatment. As its role is further elucidated, M2BPGi could potentially become a contributing factor in post-treatment surveillance strategies, with high pre-operative levels being used to identify patients at higher risk for recurrence. By being identified as individuals with a possible poorer prognosis, these patients could subsequently undergo more frequent surveillance imaging and/or AFP levels, allowing for earlier identification of recurrence and more timely intervention. As the need for novel, non-invasive HCC biomarkers remains high, this evidence in support of M2BPGi as one such encouraging candidate will ideally allow for a greater understanding of HCC prognosis and the improvement of patient outcomes.

| 1. | National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Programs. Cancer Stat Facts: Common Cancer Sites. 2025. [cited 2 December 2025]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html. |

| 2. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4428] [Article Influence: 885.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, Kudo M, Johnson P, Wagner S, Orsini LS, Sherman M. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35:2155-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 1012] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12562] [Article Influence: 6281.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 5. | Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, Jou JH, Kulik LM, Agopian VG, Marrero JA, Mendiratta-Lala M, Brown DB, Rilling WS, Goyal L, Wei AC, Taddei TH. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;78:1922-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 1148] [Article Influence: 382.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 6. | Koulouris A, Tsagkaris C, Spyrou V, Pappa E, Troullinou A, Nikolaou M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Overview of the Changing Landscape of Treatment Options. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021;8:387-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arif D, Mettler T, Adeyi OA. Mimics of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review and an approach to avoiding histopathological diagnostic missteps. Hum Pathol. 2021;112:116-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Farinati F, Marino D, De Giorgio M, Baldan A, Cantarini M, Cursaro C, Rapaccini G, Del Poggio P, Di Nolfo MA, Benvegnù L, Zoli M, Borzio F, Bernardi M, Trevisani F. Diagnostic and prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:524-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Benson AB 3rd, Abrams TA, Ben-Josef E, Bloomston PM, Botha JF, Clary BM, Covey A, Curley SA, D'Angelica MI, Davila R, Ensminger WD, Gibbs JF, Laheru D, Malafa MP, Marrero J, Meranze SG, Mulvihill SJ, Park JO, Posey JA, Sachdev J, Salem R, Sigurdson ER, Sofocleous C, Vauthey JN, Venook AP, Goff LW, Yen Y, Zhu AX. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: hepatobiliary cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:350-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kuno A, Ikehara Y, Tanaka Y, Ito K, Matsuda A, Sekiya S, Hige S, Sakamoto M, Kage M, Mizokami M, Narimatsu H. A serum "sweet-doughnut" protein facilitates fibrosis evaluation and therapy assessment in patients with viral hepatitis. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Toshima T, Shirabe K, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Kuno A, Togayachi A, Gotoh M, Narimatsu H, Korenaga M, Mizokami M, Nishie A, Aishima S, Maehara Y. A novel serum marker, glycosylated Wisteria floribunda agglutinin-positive Mac-2 binding protein (WFA(+)-M2BP), for assessing liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:76-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Nishikawa H, Enomoto H, Iwata Y, Kishino K, Shimono Y, Hasegawa K, Nakano C, Takata R, Nishimura T, Yoh K, Ishii A, Aizawa N, Sakai Y, Ikeda N, Takashima T, Iijima H, Nishiguchi S. Serum Wisteria floribunda agglutinin-positive Mac-2-binding protein for patients with chronic hepatitis B and C: a comparative study. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:977-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dolgormaa G, Harimoto N, Ishii N, Yamanaka T, Hagiwara K, Tsukagoshi M, Igarashi T, Watanabe A, Kubo N, Araki K, Handa T, Yokobori T, Oyama T, Kuwano H, Shirabe K. Mac-2-binding protein glycan isomer enhances the aggressiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating mTOR signaling. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Covidence. [cited 2 December 2025]. Available from: https://app.covidence.org/. |

| 15. | Nanashima A, Hiyoshi M, Imamura N, Hamada T, Tsuchimochi Y, Shimizu I, Ochiai T, Nagata K, Hasuike S, Nakamura K, Iwakiri H, Kawakami H. Clinical significances of several fibrotic markers for prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent hepatectomy. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13:2332-2345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 5099] [Article Influence: 268.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Ebert DD. Doing Meta-Analysis with R. 1st ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [cited 2 December 2025]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org. |

| 19. | Harimoto N, Itoh S, Yamanaka T, Hagiwara K, Ishii N, Tsukagoshi M, Watanabe A, Araki K, Yoshizumi T, Shirabe K. Mac-2 Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer as a Prognostic Marker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Sustained Virological Response. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee IC, Lei HJ, Wang LC, Yeh YC, Chau GY, Hsia CY, Chou SC, Luo JC, Hou MC, Huang YH. M2BPGi Correlated with Immunological Biomarkers and Further Stratified Recurrence Risk in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2025;14:68-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Su TH, Wu CH, Liu TH, Ho CM, Liu CJ. Clinical practice guidelines and real-life practice in hepatocellular carcinoma: A Taiwan perspective. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:230-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim BH, Park JW. Epidemiology of liver cancer in South Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nakano M, Yatsuhashi H, Bekki S, Takami Y, Tanaka Y, Yoshimaru Y, Honda K, Komorizono Y, Harada M, Shibata M, Sakisaka S, Shakado S, Nagata K, Yoshizumi T, Itoh S, Sohda T, Oeda S, Nakao K, Sasaki R, Yamashita T, Ido A, Mawatari S, Nakamuta M, Aratake Y, Matsumoto S, Maeshiro T, Goto T, Torimura T. Trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incident cases in Japan between 1996 and 2019. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yugawa K, Maeda T, Nagata S, Sakai A, Edagawa M, Omine T, Kometani T, Yamaguchi S, Konishi K, Hashimoto K. Mac-2-Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer as a Novel Predictor of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Eradication. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:2711-2719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pinheiro PS, Jones PD, Medina H, Cranford HM, Koru-Sengul T, Bungum T, Wong R, Kobetz EN, McGlynn KA. Incidence of Etiology-specific Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diverging Trends and Significant Heterogeneity by Race and Ethnicity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:562-571.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tak KY, Jang B, Lee SK, Nam HC, Sung PS, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Jang JW. Use of M2BPGi in HCC patients with TACE. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2917-2924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nakai M, Morikawa K, Hosoda S, Yoshida S, Kubo A, Tokuchi Y, Kitagataya T, Yamada R, Ohara M, Sho T, Suda G, Ogawa K, Sakamoto N. Pre-sarcopenia and Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer as predictors of recurrence and prognosis of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:1480-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yugawa K, Maeda T, Tsuji K, Shimokawa M, Sakai A, Yamaguchi S, Konishi K, Hashimoto K. Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer as a novel predictor of early recurrence after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Today. 2025;55:62-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nakagawa M, Nawa N, Takeichi E, Shimizu T, Tsuchiya J, Sato A, Miyoshi M, Kawai-Kitahata F, Murakawa M, Nitta S, Itsui Y, Azuma S, Kakinuma S, Fujiwara T, Watanabe M, Tanaka Y, Asahina Y; Ochanomizu Liver Conference Study Group. Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer as a novel predictive biomarker for patient survival after hepatitis C virus eradication by DAAs. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:990-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/