Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.114677

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 113 Days and 8.6 Hours

Endoscopy is the gold standard for examining inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and fecal calprotectin (FC) is a widely used surrogate marker for IBD. However, both methods are considered unpleasant by patients because of their invasiveness and inconvenience. Leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein (LRG) is a novel serum bio

To evaluate the predictive utility of LRG in a Taiwanese cohort.

Patients with IBD were prospectively enrolled between 2022 and 2024. Serum and stool samples were collected within 1 month of endoscopy, and patient albumin, hemoglobin (Hb), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were measured. Active endoscopic disease was defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore ≥ 2 for ulcerative colitis (UC) or a Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease ≥ 6 for Crohn’s dis

A total of 203 patients (100 with UC and 103 with CD) were enrolled. LRG was positively correlated with FC and CRP but negatively correlated with Hb and albumin (P < 0.05). In UC, the area under the curves (AUCs) for CRP, LRG, and FC in predicting endoscopic activity were 0.54, 0.56, and 0.77, respectively (P < 0.001). In CD, the corresponding AUCs were 0.69, 0.60, and 0.72 (P > 0.05). The addition of LRG modestly improved predictive ability for endoscopic activity in patients with UC. In patients with UC with low CRP levels, combining CRP, Hb, and LRG significantly improved diagnostic accuracy (AUC increased from 0.60 to 0.76, P < 0.05), achieving a performance comparable to, though slightly lower than, that of FC (AUC: 0.78).

LRG may serve as a supportive biomarker, particularly in combination with other markers, for assessing disease activity in Taiwanese patients with IBD. In patients with UC with normal CRP levels, adding LRG and Hb could enhance the pre

Core Tip: Endoscopy and fecal calprotectin (FC) are standard tools for assessing disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but both have limitations. We evaluated serum leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein (LRG) as a noninvasive biomarker in a Taiwanese IBD cohort. LRG correlated with FC, C-reactive protein (CRP), hemoglobin, and albu

- Citation: Chen YC, Weng MT, Tsai FP, Chen ZC, Wu HY, Tung CC, Wang CY, Wei SC. Role of leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein in Taiwanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease as a predictive biomarker for endoscopic activity. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 114677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/114677.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.114677

Although medical treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have advanced considerably over the past 2 decades, no definitive cure exists, and treatment response varies over time. Thus, close monitoring is essential for improving outcomes in patients with IBD. The treat-to-target strategy involves a short-term goal of achieving symptomatic response, a mid-term goal of reducing and normalizing biomarkers, and a long-term goal of achieving endoscopic healing and preventing disability[1]. Endo

C-reactive protein (CRP) is the most widely recognized and commonly used blood-based biomarker. However, it is primarily synthesized by hepatocytes in response to interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling, and its low sensitivity limits its accuracy in predicting endoscopic activity[4]. This limitation highlights the need for novel serum biomarkers or more effective combinations of blood-based tests to enhance the prediction of endoscopic activity.

Leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein (LRG) is a 50-kDa protein that was identified through proteomic analysis of IL-6- independent biomarkers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis[5], and it has attracted attention as a potential predictor of endoscopic activity. Although its precise function remains unclear, LRG is produced by neutrophils, macrophages, hepatocytes, and intestinal epithelial cells, and the presence of LRG reflects inflammation triggered by cytokines such as IL-22, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IL-1β[5,6]. LRG exacerbates colonic inflammation, partly by enhancing leukocyte trafficking through the upregulation of tumor growth factor-β1-induced endoglin expression in vascular endothelial cells[7]. These characteristics suggest that LRG may complement or even outperform CRP performances as biomarkers for IBD. Several studies of patients with IBD have reported that LRG correlates with CRP as well as clinical, endoscopic, and intestinal ultrasound assessments of disease activity[6-23]. However, nearly all of these studies were conducted in Japan[6-22,24,25], where LRG testing is currently reimbursed in clinical practice. Moreover, the reported cutoff values for LRG used to predict endoscopic activity vary across studies[12-14,18,20,24]. Findings from Japan may not be generalizable to Taiwanese patients due to differences in genetic background, environmental exposure, dietary habits, and healthcare systems. To date, the clinical utility of LRG for predicting endoscopic activity in Taiwanese patients with IBD has not been evaluated. Therefore, we investigated the predictive performance and optimal cutoff values of LRG in a Taiwanese cohort and identified the most effective combination of blood-based biomarkers for predicting endoscopic activity in IBD.

This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (approval No. 202112116RINC). All procedures followed the ethical principles for medical research involving human patients outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). Written informed consent was obtained from all par

Patients with IBD were enrolled between March 2022 and March 2024 at National Taiwan University Hospital, a tertiary referral center, during ileocolonoscopy performed for disease monitoring. Patients with infectious, autoimmune, or inflammatory conditions other than IBD were excluded from this study. As this study aimed to assess correlations between biomarkers and endoscopic disease severity, patients with inflammation limited to the proximal small bowel were excluded, as these lesions cannot be assessed by ileocolonoscopy. The Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES)[26] was used to determine the severity of ulcerative colitis (UC), and patients with an MES score of ≥ 2 were classified as having active disease. For Crohn’s disease (CD), severity was determined using the Simple Endoscopic Score for CD (SES-CD)[27], and patients with an SES-CD score of ≥ 6 were considered to have active disease. Endoscopic severity was inde

Serum samples for assessing LRG and stool samples for assessing FC were collected within 1 month of endoscopy. The stool samples were preserved at -20 °C after collection until FC levels were analyzed within 1 week.

Blood samples were collected in serum separator tubes and allowed to clot for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight. Samples were then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting serum was aliquoted and stored at -80 °C until analysis to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Serum LRG1 concentrations were quantified using a human LRG1 ELISA kit (Cosmo Bio United States, CSB-E12962h) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Levels of CRP, Hb, and Alb measured closest to the time of LRG sampling were determined from electronic medical records.

FC levels were measured using the EliA Stool Extraction Kit 2. Extraction tubes were prefilled with 1300 μL EliA Calprotectin 2 Extraction Buffer. Measurements were performed using the Phadia 200 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or as n (%). Differences in LRG, CRP, FC, Hb, and Alb levels between endoscopically active and inactive groups were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations among biomarkers (CRP, LRG, and FC), Hb, and Alb levels were evaluated using Spearman correlation analysis. Diagnostic performance and optimal cutoff values of each biomarker were determined using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC). Differences between ROC curves were analyzed using the DeLong test. Cutoff values, sensitivity, and specificity were defined using the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity-1). The effectiveness of different combinations of diagnostic tools was analyzed using logistic regression. All statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio statistical software (version 2025.05.1, Build 513, Boston, MA, United States).

A total of 203 patients with IBD were enrolled in this study between March 2022 and March 2024 (100 with UC and 103 with CD; Table 1). The median ages of the UC and CD groups were 50 years and 43 years, respectively. Male patients accounted for 54% of the UC group and 67% of the CD group. According to the Montreal classification system, the most common disease extent was extensive colitis (E3) in the UC group (82%) and ileocolonic involvement (L3) in the CD group (87.4%). A low proportion of isolated ileal disease (L1) was observed in the CD group (1.9%), likely due to the study design, which involved SES-CD scoring based on ileocolonoscopy. Patients with proximal disease beyond the reach of ileocolonoscopy were not included. Additionally, as a tertiary referral center, National Taiwan University Hospital frequently manages more complex and severe cases, which may partly explain the higher proportion of extensive disease in this cohort. Active endoscopic disease was observed in 49% of patients with UC (MES ≥ 2) and 26.2% of patients with CD (SES-CD ≥ 6).

| UC (n = 100) | CD (n = 103) | |

| Male sex | 54 (54.0) | 69 (67.0) |

| Age (years old), median (IQR) | 50 (40-61) | 43 (33-56) |

| Time interval, day, median (IQR)1 | 11.5 (3-24) | 15.5 (6.5-24) |

| Disease extent | ||

| E1 | 2 (2.0) | - |

| E2 | 16 (16.0) | - |

| E3 | 82 (82.0) | - |

| L1 | - | 2 (1.9) |

| L2 | - | 11 (10.7) |

| L3 | - | 90 (87.4) |

| Upper GI modifier | - | 5 (4.9) |

| Perianal disease modifier | - | 14 (13.6) |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | ||

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.5 (12.5-14.5) | 13.9 (12.6-15) |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.5 (4.3-4.7) | 4.5 (4.4-4.8) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.05-0.23) | 0.11 (0.05-0.33) |

| LRG (μg/mL) | 8.6 (7.05-11.1) | 9.0 (6.9-12.1) |

| FC (mg/kg) | 47.5 (17-230) | 68 (32-257) |

| Endoscopic activity | ||

| MES < 2 | 51 (51) | - |

| MES ≥ 2 | 49 (49) | - |

| SES-CD < 6 | - | 76 (73.8) |

| SES-CD ≥ 6 | - | 27 (26.2) |

| Clinical disease activity, median (IQR) | ||

| Partial Mayo score | 0 (0-1) | - |

| HBI | - | 1 (0-2) |

| Medications | ||

| No current therapies | 3 (3.0) | 8 (7.8) |

| 5-ASA | 91 (91.0) | 15 (14.6) |

| Immunomodulators | 16 (16.0) | 57 (55.3) |

| Corticosteroid | 9 (9.0) | 3 (2.9) |

| Biologics | ||

| Anti-TNF | 2 (2.0) | 40 (38.8) |

| Anti-integrin | 17 (17.0) | 5 (4.9) |

| Anti-IL12/23 or anti-IL23 | 5 (5.0) | 19 (18.4) |

| JAK inhibitor | 9 (9.0) | 1 (1.0) |

The median Hb levels were 13.5 g/dL and 13.9 g/dL in the UC and CD groups, respectively, with corresponding IQRs of 12.5-14.5 g/dL and 12.6-15.0 g/dL. The median Alb level was 4.5 g/dL in the UC and CD groups, with the groups having IQRs of 4.3-4.7 g/dL and 4.4-4.8 g/dL, respectively. The median CRP levels were 0.10 mg/dL and 0.11 mg/dL in the UC and CD groups, respectively, with corresponding IQRs of 0.05-0.23 mg/dL and 0.05-0.33 mg/dL. The median serum LRG levels were 8.6 μg/mL and 9.0 μg/mL in the UC and CD groups, respectively, with corresponding IQRs of 7.05-11.1 μg/mL and 6.9-12.1 μg/mL. Furthermore, the median FC levels were 47.5 mg/kg and 68 mg/kg in the UC and CD groups, respectively, with corresponding IQRs of 17-230 mg/kg and 32-257 mg/kg.

Spearman correlation analysis revealed that serum LRG was significantly associated with multiple biomarkers (Table 2). In all patients with IBD, LRG was significantly and positively correlated with FC (r = 0.155, P = 0.028) and CRP (r = 0.565, P < 0.001). In contrast, LRG was negatively correlated with Hb (r = -0.479, P < 0.001) and Alb (r = -0.484, P < 0.001). Among patients with UC, LRG was significantly and positively correlated with FC (r = 0.201, P = 0.045) and CRP (r = 0.376, P < 0.001) but negatively correlated with Hb (r = -0.489, P < 0.001) and Alb (r = -0.358, P < 0.001). In patients with CD, LRG was strongly correlated with CRP (r = 0.629, P < 0.001) but exhibited only a weak, nonsignificant positive correlation with FC (r = 0.179, P = 0.07). LRG also demonstrated significant and negative correlations with Hb (r = -0.495, P < 0.001) and Alb (r = -0.584, P < 0.001). Overall, LRG correlated more strongly with blood-based biomarkers than with FC.

| CRP | Alb | Hb | FC | |||

| IBD | Correlation coefficient | LRG | 0.565 | -0.484 | -0.479 | 0.155 |

| Two-tailed significance | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.028 | ||

| UC | Correlation coefficient | LRG | 0.376 | -0.358 | -0.489 | 0.201 |

| Two-tailed significance | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.045 | ||

| CD | Correlation coefficient | LRG | 0.629 | -0.584 | -0.495 | 0.179 |

| Two-tailed significance | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

When biomarker levels were compared between endoscopically active and inactive groups (Table 3), the serum LRG levels were significantly higher in patients with IBD (P = 0.049) and CD (P = 0.012) with active disease but only numerically higher in patients with UC (P = 0.431). CRP level was significantly increased in patients with endoscopically active CD (P = 0.019) but not in patients with UC (P = 0.815) or in the overall IBD cohort (P = 0.079). In contrast, the FC level was consistently and significantly higher in patients with endoscopically active disease in the IBD (P < 0.001), UC

| Active | Inactive | P value | |

| IBD | |||

| LRG, μg/mL | 9.5 (7.25-11.75) | 8.5 (6.75-11.2) | 0.049a |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.13 (0.06-0.33) | 0.08 (0.04-0.23) | 0.079 |

| Hb, g/dL | 13.9 (12.6-15.0) | 13.7 (12.5-14.6) | 0.403 |

| Alb, g/dL | 4.5 (4.3-4.7) | 4.5 (4.4-4.8) | 0.582 |

| FC, mg/kg | 217 (45-880) | 47 (18-132) | < 0.001a |

| UC | |||

| LRG, μg/mL | 8.8 (7.5-11.2) | 8.3 (6.7-11) | 0.431 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.11 (0.05-0.23) | 0.08 (0.05-0.21) | 0.815 |

| Hb, g/dL | 14 (12.8-14.8) | 13.3 (12.4-14.5) | 0.221 |

| Alb, g/dL | 4.6 (4.3-4.8) | 4.5 (4.4-4.7) | 0.905 |

| FC, mg/kg | 102 (45-1336) | 31 (10-79.5) | 0.006a |

| CD | |||

| LRG, μg/mL | 11 (7-16.5) | 8.6 (6.9-11.4) | 0.012a |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.2 (0.1-0.65) | 0.09 (0.04-0.23) | 0.019a |

| Hb, g/dL | 14.3 (12.2-15.5) | 13.9 (12.8-14.6) | 0.753 |

| Alb, g/dL | 4.5 (4.4-4.6) | 4.5 (4.4-4.8) | 0.269 |

| FC, mg/kg | 273 (55-626) | 57.5 (27-167) | < 0.001a |

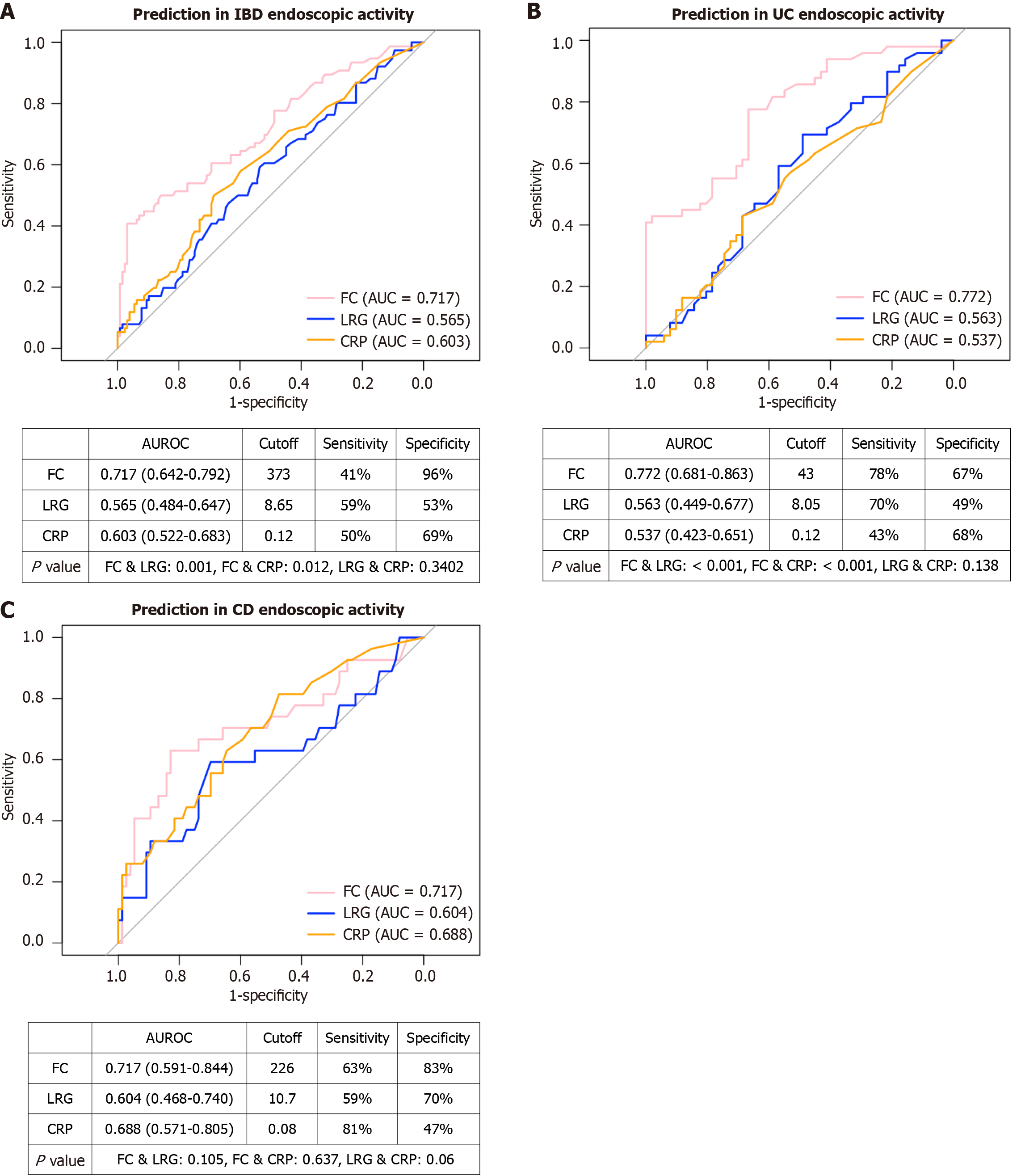

As comparisons between the endoscopically active and inactive groups revealed significant differences in LRG, CRP, and FC levels, we performed ROC curve analyses to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy and optimal cutoff values of each biomarker for predicting active endoscopic disease, defined as an MES score of ≥ 2 for UC and an SES-CD score of ≥ 6 for CD (Figure 1). In all patients with IBD (Figure 1A), the area under the curves (AUCs) of CRP, LRG, and FC were 0.60, 0.57, and 0.72, respectively. The optimal cutoff values were 0.12 mg/dL for CRP, 8.65 μg/mL for LRG, and 373 mg/kg for FC. FC demonstrated significantly greater predictive power than CRP (P = 0.012) and LRG (P = 0.001), whereas there was no significant difference in predictive power between CRP and LRG (P = 0.34). Among patients with UC (Figure 1B), the AUCs were 0.54 for CRP, 0.56 for LRG, and 0.77 for FC. The cutoff values were 0.12 mg/dL for CRP, 8.05 μg/mL for LRG, and 43 mg/kg for FC. FC demonstrated significantly greater predictive power than CRP (P < 0.001) and LRG (P < 0.001); however, there was no difference in predictive power between CRP and LRG (P = 0.14). In patients with CD (Figure 1C), the AUCs were 0.69 for CRP, 0.60 for LRG, and 0.72 for FC. The cutoff values were 0.08 mg/dL for CRP, 10.7 μg/mL for LRG, and 226 mg/kg for FC. No significant difference in predictive power was observed among the three biomarkers (P > 0.05). Overall, FC demonstrated the strongest predictive ability among all biomarkers. LRG numerically outperformed CRP in UC but exhibited comparable performance in CD.

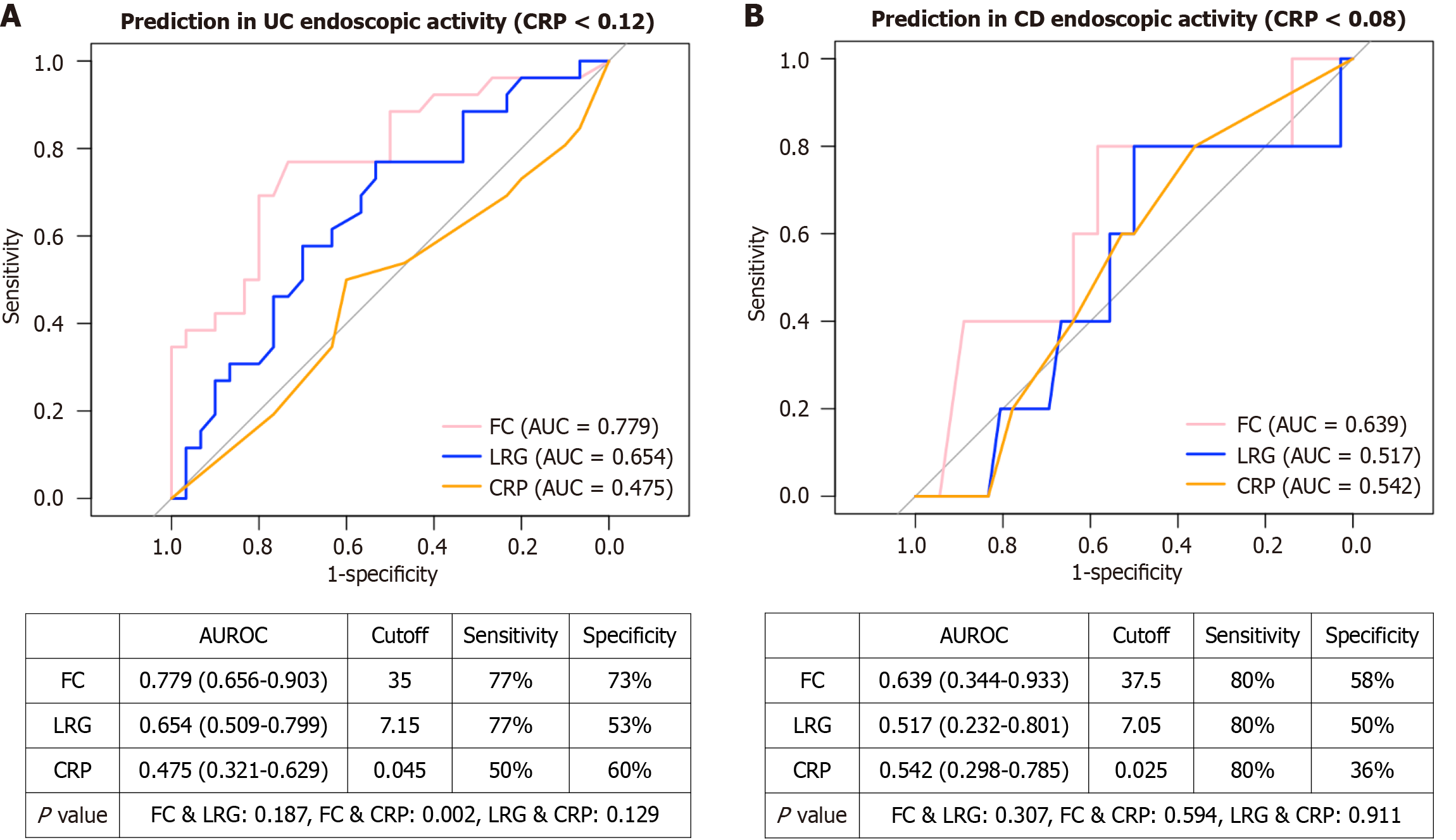

We further conducted subgroup analyses for the UC and CD groups to determine whether LRG has greater utility in patients with normal CRP levels (Figure 2). Among patients with UC with a CRP level of < 0.12 mg/dL (cutoff), the AUCs of CRP, LRG, and FC were 0.48, 0.65, and 0.78, respectively. The optimal cutoff values were 0.05 mg/dL for CRP, 7.15 μg/mL for LRG, and 35 mg/kg for FC. Under these conditions, there was no significant difference in predictive ability between FC and LRG (P = 0.19), although FC still outperformed CRP (P = 0.002). Among patients with CD with a CRP level of < 0.08 mg/dL (cutoff), the AUCs of CRP, LRG, and FC were 0.54, 0.51, and 0.64, respectively. The optimal cutoff values were 0.03 mg/dL for CRP, 7.05 μg/mL for LRG, and 37.5 mg/kg for FC. In this subgroup, there were no significant differences in predictive ability among the biomarkers.

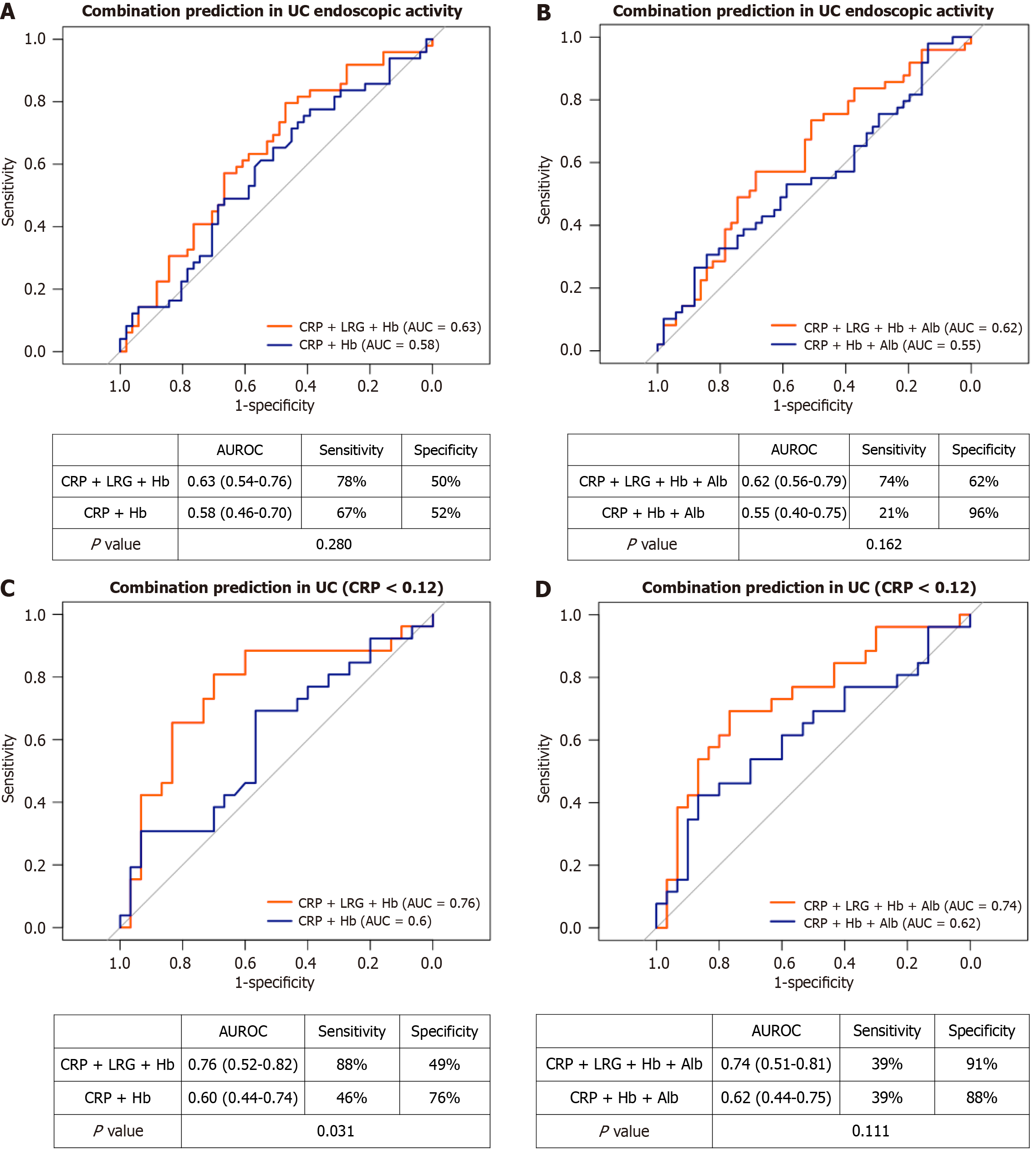

We explored whether combining blood-based biomarkers could improve predictive accuracy for endoscopic activity to nearly that of FC. In patients with UC (Figure 3), the AUCs for the combinations CRP + Hb, CRP + LRG + Hb, CRP + Hb + Alb, and CRP + LRG + Hb + Alb were 0.58, 0.63, 0.55, and 0.62, respectively (Figure 3A and B). Among patients with UC with a CRP level of < 0.12 mg/dL, the corresponding AUCs were 0.60, 0.76, 0.62, and 0.74 (Figure 3C and D). In this subgroup, the addition of LRG significantly improved predictive performance (the AUC increased from 0.60 to 0.76 for CRP + Hb + LRG, P = 0.03, and from 0.62 to 0.74 for CRP + Hb + Alb + LRG, P = 0.11); however, the overall performance remained lower than that of FC.

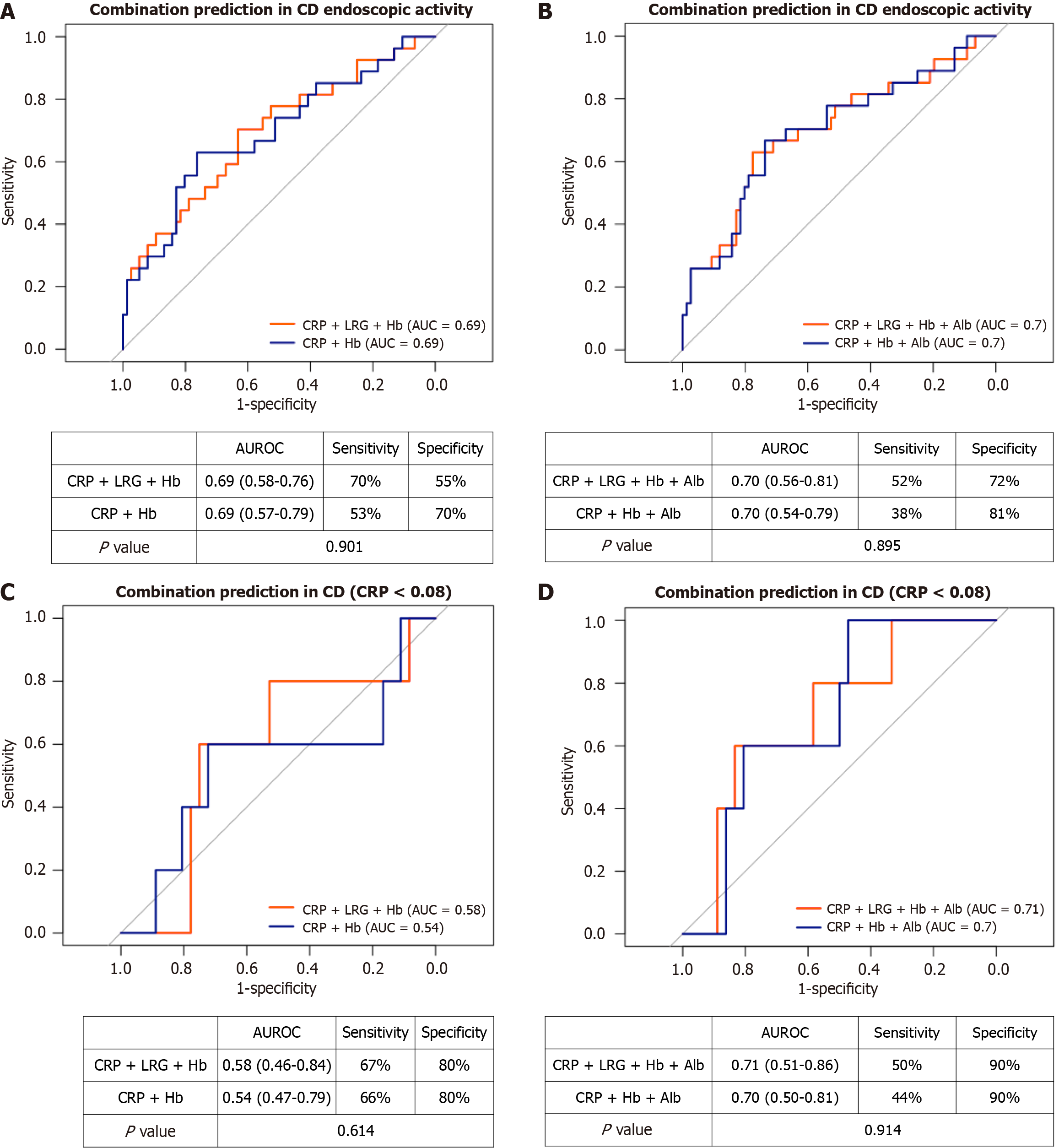

In patients with CD (Figure 4), the AUCs for the combinations of CRP + Hb, CRP + LRG + Hb, CRP + Hb + Alb, and CRP + LRG + Hb + Alb were 0.69, 0.69, 0.70, and 0.70, respectively (Figure 4A and B). In patients with a CRP level of < 0.08 mg/dL, the corresponding AUCs of these combinations were 0.54, 0.58, 0.70, and 0.71 (Figure 4C and D). Adding LRG did not significantly improve prediction, likely because CRP alone already exhibited strong predictive value and was highly correlated with LRG in CD.

Because CRP and LRG are acute-phase proteins with short half-lives and rapidly change in response to inflammation, we were concerned that a 1-month sampling window could introduce temporal bias. To investigate this, we re-analyzed samples collected within 7 days and 14 days and compared the AUCs with the 1-month group. As shown in Supple

These results suggest that FC is the most reliable noninvasive marker for predicting endoscopic activity in IBD. Our study validates LRG as a noninvasive biomarker in Taiwanese patients with IBD and demonstrates its greatest utility for patients with UC with low CRP levels. When combined with Hb and CRP, the diagnostic performance of LRG improved to nearly that of FC.

Close monitoring can improve outcomes in patients with IBD, and among the available monitoring tools, blood-based assessments are generally preferred over stool- or endoscopy-based methods because they offer greater convenience and comfort[3]. To date, most studies on LRG in patients with IBD has been conducted in Japanese cohorts[3,6-25]. Our study is the first to evaluate the clinical utility of LRG in a non-Japanese population. In addition to confirming correlations between LRG, CRP, and FC, we demonstrated that LRG levels were negatively correlated with Alb and Hb levels. This is the first study to determine the diagnostic performance of combining blood-based tests, including traditional markers (CRP, Hb, and Alb) and the novel biomarker LRG, in patients with IBD.

Although CRP remains the most widely used serum biomarker in IBD, it has notable limitations, particularly in cases of UC (AUC: 0.53). In our cohort, LRG was positively correlated with CRP and FC but negatively correlated with Hb and Alb. A recent study reported that LRG had a greater predictive ability for endoscopic activity than CRP in CD and UC[28,29]. However, our findings reveal differential utility for CRP; CRP demonstrated strong diagnostic performance in CD but not in UC, wherein most patients had low or normal CRP values (median: 0.1 mg/dL; range: 0.02-5.5 mg/dL; IQR: 0.05-0.23 mg/dL). This finding highlights that additional biomarkers or biomarker combinations are required in cases of UC. The addition of LRG resulted in only a nonsignificant increase in the AUROC (from 0.58 to 0.63) for all patients with UC. Notably, the combination of blood-based tests provided the greatest benefit for patients with UC who had low CRP levels (AUROC increased from 0.60 to 0.76). In CD, CRP and LRG levels significantly differed between endoscopically active and inactive subgroups. However, ROC analysis revealed that adding LRG did not improve AUROC, even in patients with CD who had low CRP levels. These findings suggest that CRP alone is sufficient as a serum biomarker for disease assessment in CD.

In our cohort, the optimal LRG cutoff values for predicting active endoscopic disease (MES ≥ 2 for UC and SES-CD ≥ 6 for CD) were 8.1 μg/mL for UC and 10.8 μg/mL for CD. The corresponding AUCs were 0.56 for UC, 0.60 for CD, and 0.57 for all patients with IBD. These AUROCs were lower than those reported in Japanese cohorts (AUC: 0.68-0.82)[6,23]. These findings should be further validated in Western populations to confirm their generalizability. Regarding this study, the differences between our findings and those from Japanese populations may be explained by several factors. First, because LRG production is regulated by multiple cytokines[5,6], genetic polymorphisms affecting these pathways may contribute to ethnic differences. Second, we utilized an ELISA kit (Cosmo Bio United States, CSB-E12962h) for LRG measurements, which was distinct from previous Japanese studies (IBL, Fujioka, Japan[6], or Nanopia LRG, Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan[16,20,24]). Third, patients in our cohort were largely in biochemical remission, with low median CRP and FC levels. In a narrower disease severity spectrum, the performance of LRG in distinguishing endo

Reported LRG cutoff values have varied widely across studies in this field, likely because of differences regarding disease endpoints (e.g., clinical activity, endoscopic remission, small bowel involvement, transmural inflammation, and endoscopic activity). As summarized in Table 4, the cutoff values we used in this study were higher for detecting small bowel involvement, which may indicate more severe inflammation. In addition to the explained differences from the genetic background, testing kits, and disease severity distribution, it is essential for local validation and calibration prior to the adoption of LRG. Another strategy is to combine different parameters. Shimoyama et al[16] analyzed clinical and endoscopic activity in UC and CD and reported increased specificity and positive likelihood ratios when LRG and CRP levels were higher than their respective cutoff values. Similarly, Takada et al[28] also reported that combining LRG and CRP improved specificity for predicting moderate-to-severe endoscopic activity in CD. Consistent with these findings, our results revealed the additive value of LRG to CRP, particularly in patients with UC. Moreover, the inclusion of Alb and Hb, parameters routinely monitored in clinical practice, further enhanced predictive accuracy and showed negative correlations with LRG.

| Reference | Endpoints/AUC | Sensitivity/specificity | Cutoff for LRG |

| Serada et al[6], 2012 | UC/clinical CAI | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.901 | 84.0%/82.5% | 7.21 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.845 | 80.0%/80.7% | 0.20 |

| Takenaka et al[17], 2023 | CD/transmural inflammation | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.845 | 67%/90% | 14 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.766 | 48%/94% | 0.03 |

| Asonuma et al[12], 2023 | CD/small bowel lesions | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.77 | 89.0%/100% | 9/16 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.74 | 50%/89% | 1 |

| Shimoyama et al[16], 2023 | IBD/MES > 0 or SES-CD > 2 | ||

| LRG (UC), μg/mL | 0.80 | 71%/85% | 12.7 |

| CRP (UC), mg/dL | 0.72 | 56%/80% | 0.14 |

| LRG (CD), μg/mL | 0.79 | 88%/63% | 13.3 |

| CRP (CD), mg/dL | 0.78 | 65%/75% | 0.46 |

| IBD/partial Mayo > 0/CDAI > 150 | |||

| LRG (UC), μg/mL | 0.73 | 69%/73% | 12.7 |

| CRP (UC), mg/dL | 0.63 | 66%/53% | 0.08 |

| LRG (CD), μg/mL | 0.71 | 67%/71% | 22.2 |

| CRP (CD), mg/dL | 0.64 | 64%/68% | 0.9 |

| Takada et al[28], 2025 | CD/SES-CD > 6 | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.74 | 70.8%/87.5% | 15.5 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.63 | 58.3%/71.9% | 0.13 |

| Aoyama et al[29], 2025 | UC/MES > 1 | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.68 | 50%/82% | 14.8 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.62 | 44%/83% | 0.21 |

| Ojaghi Shirmard et al[23], 2025 | IBD/meta-analysis | ||

| LRG, μg/mL | 0.82 | 75.4%/77.3% | - |

| Current study | IBD/MES ≥ 2 for UC, SES-CD ≥ 6 | ||

| LRG (UC), μg/mL | 0.57 | 69%/50% | 8.1 |

| CRP (UC), mg/dL | 0.45 | 98%/6% | 1.01 |

| LRG (CD), μg/mL | 0.61 | 59%/70% | 10.8 |

| CRP (CD), mg/dL | 0.70 | 85%/46% | 0.08 |

In our study, LRG exhibited a nonsignificant correlation with FC among patients with CD. Biologically, LRG ex

Although the AUC value of LRG was lower than that of FC in our study, LRG may still serve as a useful complementary biomarker, particularly when stool collection is difficult or when a more comprehensive evaluation of systemic inflammation is desired. As LRG is induced by multiple inflammatory cytokines beyond those reflected by FC, it may detect additional aspects of inflammation, including systemic or deeper tissue activity. Clinicians may use LRG for frequent monitoring and reserve FC for confirmatory testing or when precise quantification of mucosal inflammation is needed.

Considering cost and accessibility, LRG testing is not routinely implemented in clinical practice and remains largely confined to research settings in Taiwan. The cost of LRG testing is approximately US$16-25 per test, whereas CRP testing is considerably cheaper at around US$7-10 per test. In contrast, FC testing remains relatively expensive in many Asian countries, typically ranging from US$50-70 per test, often imposing a substantial financial burden on patients. Overall, LRG testing is less expensive than FC but not yet widely available for routine clinical use.

This study has several strengths. First, it included serum and fecal biomarkers, which enabled direct comparison of their diagnostic performance for endoscopic activity. Second, this is the first study to evaluate the predictive value of LRG in a Taiwanese IBD population, establishing a path for broader investigation and application in this area. Third, this is the first study to report real-world findings on combining LRG with routinely used blood biomarkers.

This study also has several limitations. First, data were collected within 1 month of endoscopy, which represents a relatively long interval that could substantially reduce the accuracy of blood-based biomarkers. Given that CRP and LRG are acute-phase proteins with short plasma half-lives and rapid fluctuations in response to inflammation, such a wide sampling window likely introduced temporal bias and may have considerably attenuated the observed associations with endoscopic activity. However, in clinical practice, patients often undergo endoscopy weeks before follow-up visits and complete laboratory tests only a few days prior. Second, the number of patients with active CD was small because most participants were on maintenance therapy rather than being newly diagnosed, which reduced the statistical power of subgroup analysis. Third, this study was conducted at a single tertiary referral center, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Although the sample size was reasonable, it remains modest. Additional multicenter studies with larger and more diverse cohorts and with biomarker and endoscopy data collected within a shorter interval are warranted to confirm our findings and refine optimal cutoff values for LRG in monitoring disease activity, remission, and mucosal healing.

This is the first study to evaluate LRG as a serum biomarker for predicting endoscopic disease activity in a Taiwanese IBD population. It is also the first study to demonstrate that combining LRG with CRP, Alb, and Hb enhances the predictive performance of serum biomarkers, with the performance nearing that of FC. Although FC remains the most reliable noninvasive test for detecting endoscopic activity, our findings support the integration of LRG into routine blood-based monitoring for IBD, particularly among patients with UC who have low CRP levels.

We thank the staff of the Second Core Lab, Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital, for providing technical support during the study.

| 1. | Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Schölmerich J, Bemelman W, Danese S, Mary JY, Rubin D, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Abreu MT, Dignass A; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 1967] [Article Influence: 393.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lin WC, Wong JM, Tung CC, Lin CP, Chou JW, Wang HY, Shieh MJ, Chang CH, Liu HH, Wei SC; Taiwan Society of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multicenter Study. Fecal calprotectin correlated with endoscopic remission for Asian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13566-13573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Christensen KR, Steenholdt C, Buhl S, Brynskov J, Ainsworth MA. A systematic monitoring approach to biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: patients' and physicians' preferences and adherence. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:274-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mosli MH, Zou G, Garg SK, Feagan SG, MacDonald JK, Chande N, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG. C-Reactive Protein, Fecal Calprotectin, and Stool Lactoferrin for Detection of Endoscopic Activity in Symptomatic Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:802-19; quiz 820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Serada S, Fujimoto M, Ogata A, Terabe F, Hirano T, Iijima H, Shinzaki S, Nishikawa T, Ohkawara T, Iwahori K, Ohguro N, Kishimoto T, Naka T. iTRAQ-based proteomic identification of leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a novel inflammatory biomarker in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:770-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Serada S, Fujimoto M, Terabe F, Iijima H, Shinzaki S, Matsuzaki S, Ohkawara T, Nezu R, Nakajima S, Kobayashi T, Plevy SE, Takehara T, Naka T. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a disease activity biomarker in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2169-2179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mishima T, Fujimoto M, Urushima H, Funajima E, Suzuki Y, Ohkawara T, Murata O, Serada S, Naka T. A Role for Leucine-Rich α2-Glycoprotein in Leukocyte Trafficking and Mucosal Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31:1637-1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Komatsu M, Sagami S, Hojo A, Karashima R, Maeda M, Yamana Y, Serizawa K, Umeda S, Asonuma K, Nakano M, Hibi T, Matsuda T, Kobayashi T. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein Is Associated With Transmural Inflammation Assessed by Intestinal Ultrasound in Patients With Crohn's Disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61:658-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shinzaki S, Matsuoka K, Iijima H, Mizuno S, Serada S, Fujimoto M, Arai N, Koyama N, Morii E, Watanabe M, Hibi T, Kanai T, Takehara T, Naka T. Leucine-rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein is a Serum Biomarker of Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:84-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shinzaki S, Matsuoka K, Tanaka H, Takeshima F, Kato S, Torisu T, Ohta Y, Watanabe K, Nakamura S, Yoshimura N, Kobayashi T, Shiotani A, Hirai F, Hiraoka S, Watanabe M, Matsuura M, Nishimoto S, Mizuno S, Iijima H, Takehara T, Naka T, Kanai T, Matsumoto T. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a potential biomarker to monitor disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease receiving adalimumab: PLANET study. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:560-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoshimura T, Mitsuyama K, Sakemi R, Takedatsu H, Yoshioka S, Kuwaki K, Mori A, Fukunaga S, Araki T, Morita M, Tsuruta K, Yamasaki H, Torimura T. Evaluation of Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein as a New Inflammatory Biomarker of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2021;2021:8825374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Asonuma K, Kobayashi T, Kikkawa N, Nakano M, Sagami S, Morikubo H, Miyatani Y, Hojo A, Fukuda T, Hibi T. Optimal Use of Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein as a Biomarker for Small Bowel Lesions of Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2023;8:13-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ichimiya T, Kazama T, Ishigami K, Yokoyama Y, Hayashi Y, Takahashi S, Itoi T, Nakase H. Application of plasma alternative to serum for measuring leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein as a biomarker of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0286415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ito T, Dai K, Horiuchi M, Horii T, Furukawa S, Maemoto A. Monitoring of leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein and assessment by small bowel capsule endoscopy are prognostic for Crohn's disease patients. JGH Open. 2023;7:645-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nasuno M, Shimazaki H, Nojima M, Hamada T, Sugiyama K, Miyakawa M, Tanaka H. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein levels for predicting active ultrasonographic findings in intestinal lesions of patients with Crohn's disease in clinical remission. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shimoyama T, Yamamoto T, Yoshiyama S, Nishikawa R, Umegae S. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein Is a Reliable Serum Biomarker for Evaluating Clinical and Endoscopic Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1399-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Takenaka K, Kitazume Y, Kawamoto A, Fujii T, Udagawa Y, Wanatabe R, Shimizu H, Hibiya S, Nagahori M, Ohtsuka K, Sato H, Hirakawa A, Watanabe M, Okamoto R. Serum Leucine-Rich α2 Glycoprotein: A Novel Biomarker for Transmural Inflammation in Crohn's Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1028-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yasuda R, Arai K, Kudo T, Nambu R, Aomatsu T, Abe N, Kakiuchi T, Hashimoto K, Sogo T, Takahashi M, Etani Y, Kato K, Yamashita Y, Mitsuyama K, Mizuochi T. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein and calprotectin in children with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:1131-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Amano T, Yoshihara T, Shinzaki S, Sakakibara Y, Yamada T, Osugi N, Hiyama S, Murayama Y, Nagaike K, Ogiyama H, Yamaguchi T, Arimoto Y, Kobayashi I, Kawai S, Egawa S, Kizu T, Komori M, Tsujii Y, Asakura A, Tashiro T, Tani M, Otake-Kasamoto Y, Uema R, Kato M, Tsujii Y, Inoue T, Yamada T, Kitamura T, Yonezawa A, Iijima H, Hayashi Y, Takehara T. Selection of anti-cytokine biologics by pretreatment levels of serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep. 2024;14:29755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Horiuchi I, Horiuchi K, Horiuchi A, Umemura T. Serum Leucine-Rich α2 Glycoprotein Could Be a Useful Biomarker to Differentiate Patients with Normal Colonic Mucosa from Those with Inflammatory Bowel Disease or Other Forms of Colitis. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Karashima R, Sagami S, Yamana Y, Maeda M, Hojo A, Miyatani Y, Nakano M, Matsuda T, Hibi T, Kobayashi T. Early change in serum leucine-rich α-2-glycoprotein predicts clinical and endoscopic response in ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2024;22:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yoshimura S, Okata Y, Ooi M, Horinouchi T, Iwabuchi S, Kameoka Y, Watanabe A, Kondo A, Uemura K, Tomioka Y, Samejima Y, Nakai Y, Nozu K, Kodama Y, Bitoh Y. Significance of Serum Leucine-rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein as a Diagnostic Marker in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Kobe J Med Sci. 2024;69:E122-E128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ojaghi Shirmard F, Pourfaraji SM, Saeedian B, Bagheri T, Ismaiel A, Matsumoto S, Babajani N. The usefulness of serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a novel biomarker in monitoring inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;37:891-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoshida T, Shimodaira Y, Fukuda S, Watanabe N, Koizumi S, Matsuhashi T, Onochi K, Iijima K. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Monitoring Disease Activity and Intestinal Stenosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022;257:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ondriš J, Husťak R, Ďurina J, Malicherová Jurková E, Bošák V. Serum Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Anything New on the Horizon? Folia Biol (Praha). 2024;70:248-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2327] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Daperno M, D'Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, Sostegni R, Rocca R, Pera A, Gevers A, Mary JY, Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 999] [Cited by in RCA: 1388] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takada Y, Kiyohara H, Mikami Y, Taguri M, Sakakibara R, Aoki Y, Nanki K, Kawaguchi T, Yoshimatsu Y, Sugimoto S, Sujino T, Takabayashi K, Hosoe N, Ogata H, Kato M, Iwao Y, Nakamoto N, Kanai T. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein in combination with C-reactive protein for predicting endoscopic activity in Crohn's disease: a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Ann Med. 2025;57:2453083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Aoyama Y, Hiraoka S, Yasutomi E, Inokuchi T, Tanaka T, Takei K, Igawa S, Takeuchi K, Takahara M, Toyosawa J, Yamasaki Y, Kinugasa H, Kato J, Okada H, Otsuka M. Changes of leucine-rich alpha 2 glycoprotein could be a marker of changes of endoscopic and histologic activity of ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:5248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 1253] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/