Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.114226

Revised: October 29, 2025

Accepted: December 5, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 124 Days and 15.5 Hours

Hydatid cyst disease of the liver remains a significant public health problem in endemic regions. While surgical treatment has traditionally been the mainstay of therapy, minimally invasive percutaneous approaches have emerged as safe and effective alternatives, especially for selected World Health Organization (WHO) cystic echinococcosis (CE) 1 and CE3a cysts. Comparative data on efficacy, com

To compare and evaluate the efficacy, safety, complication rates, and clinical course of WHO CE1 and CE3a liver hydatid cysts treated with surgical and per

A total of 989 patients diagnosed with liver hydatid cyst and treated either surgically (n = 734) or percutaneously (n = 255) between 2005 and 2025 were included in the study. Demographic data, treatment process, complications, and recurrence rates of the retrospectively evaluated patients were recorded. Cyst volume, hospital stay duration, and catheter removal times were compared. Cases with and without fistula development were also analyzed separately.

There was no significant difference between the surgical (n = 734) and percutaneous (n = 255) groups in terms of gender (female: 76.0% vs 72.2%; P = 0.250) and age (38.4 ± 15.9 years vs 38.1 ± 16.1 years; P = 0.800), respectively. Operation time (85.6 ± 34.5 minutes vs 40.3 ± 15.7 minutes; P < 0.001), hospital stay duration (7.3 ± 6.2 days vs 3.1 ± 2.3 days; P < 0.001), catheter removal time (6.6 ± 5.3 days vs 5.5 ± 6.4 days; P = 0.014), and intraoperative organ injury rate (2.7% vs 0%; P = 0.002) were significantly longer/higher in the surgical group compared to the per

For treatment of WHO CE1 and CE3a liver cysts, the percutaneous approach is a safe and effective method due to shorter hospital stays, minimal invasiveness, and negligible risk of intraoperative organ injury, whereas surgical methods appear marginally advantageous regarding recollection and anaphylaxis. In both groups, higher cyst volume increases the risk of fistula and may prolong the treatment process. Patient selection should consider these parameters.

Core Tip: This large-scale, retrospective study compares percutaneous and surgical treatments for World Health Organization cystic echinococcosis (CE) 1 and CE3a liver hydatid cysts over a 20-year period. Based on real-world data from an endemic region, the study highlights the safety and efficacy of percutaneous approaches, while also showing slightly lower recollection rates with surgery. Notably, the findings suggest that higher cyst volume increases the risk of fistula formation and prolongs treatment, regardless of the method used. These insights can help guide personalized treatment decisions and emphasize the need for standardizing follow-up protocols and recurrence definitions in future studies.

- Citation: Tahtabasi M, Kaya E, Yalcin M, Kaya V. Percutaneous vs surgical management of World Health Organization cystic echinococcosis 1 and 3a liver hydatid cysts. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(3): 114226

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i3/114226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i3.114226

Hydatid disease is an endemic zoonotic infection caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus and remains a major public health problem in regions such as the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and South America[1]. Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, which distinguish active cysts requiring treatment from inactive ones (CE4 and CE5). Even asymptomatic viable cysts should be treated because of the risk of life-threatening complications[2,3]. Surgery has traditionally been the mainstay of treatment, but percutaneous techniques such as puncture, aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration (PAIR) and catheter drainage have emerged[4-7]. The growing adoption of minimally invasive management, studies directly comparing long-term outcomes of surgical and percutaneous treatment remain limited, and consensus on recurrence rates is lacking.

As part of the HERACLES project, which investigates the burden of CE in endemic regions, Sanliurfa in southeastern Turkey has been identified as an important data center[8]. In this study, we deliberately included only WHO CE1 and CE3a cysts, as these are the most commonly encountered types in daily clinical practice and are the most amenable to percutaneous interventions. Their predominantly unilocular, fluid-filled morphology facilitates safe puncture and complete evacuation during PAIR or catheter-based techniques. In contrast, CE2 and CE3b cysts often contain multiple daughter cysts or partially detached membranes, which complicate drainage, reduce procedural success, and increase the risk of recurrence or recollection. This study compares surgical and percutaneous management of CE1 and CE3a liver hydatid cysts in this high-prevalence region, evaluating complications, hospital stay, and recurrence to address a major evidence gap in the literature.

This retrospective study was conducted at the largest tertiary referral hospital in Sanliurfa, a province located in southeastern Türkiye, where hydatid cyst disease is endemic. The study included patients diagnosed with hepatic hydatid cysts between July 2005 and September 2025. Patients who had received only medical treatment were excluded, underwent surgery for CE2 or CE3b cysts, had ruptured cysts, lacked accessible medical records, or were younger 18 years of age. Only patients with CE1 or CE3a cysts who underwent surgical or percutaneous treatment and had available follow-up data were included in the analysis.

Demographic data (age and sex), cyst type and size, pre- and post-treatment cyst volumes, occurrence of major and minor complications, presence of cysto-biliary fistula, catheter removal time, length of hospital stay, recurrence or recollection status, and treatment modality were obtained from electronic medical records. Patients were categorized and compared based on the presence or absence of fistula formation and the type of treatment received (surgery vs per

All patients received oral albendazole tablets (10 mg/kg/day) for at least two weeks prior to the procedure to prevent intraperitoneal dissemination and recurrence[9]. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia in an operating room environment due to the risk of anaphylactic shock. The standard catheterization technique described by Akhan et al[10] was used for percutaneous treatment. Procedures were performed using the Seldinger technique under ultrasound (US) and fluoroscopic guidance. To prevent intraperitoneal dissemination, a minimum of 1 cm of normal liver tissue was traversed[11]. Under US guidance, an 18-gauge needle was introduced into the cyst cavity, and approximately 10% of the cyst volume was aspirated. Then, 10-30 mL of contrast medium was injected for cystography, and a 0.035-inch Amplatz guidewire (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, United States) was inserted. Depending on the cyst content, an 8-12 French pigtail drainage catheter was placed. To exclude cystobiliary communication before scolicidal therapy, the aspirated fluid was first inspected macroscopically for bile. Cystography was repeated under fluoroscopy with 10-30 mL of contrast medium. Absence of bile in the fluid and no opacification of the biliary tree were considered indicative of no biliary communication, and 20% hypertonic saline followed by 95% ethanol (30%-40% of cyst volume) was instilled for at least 10 minutes before respiration. If bile was present macroscopically or contrast passed into the biliary tree, ethanol instillation was avoided to prevent sclerosing cholangitis, and the catheter was left in place for follow-up. Scolicidal therapy was applied only after closure of the bile fistula. The catheter was removed once daily drainage fell below 10 mL. Persistent bile leakage was managed with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy and biliary stenting[11].

In open surgery, a laparotomy was performed via a subcostal incision to expose the cyst. In laparoscopic surgery, four ports were inserted one for the camera through the infraumbilical region and three others depending on the cyst location for optimal access around the liver. Surrounding tissues were protected using gauze soaked in a scolicidal agent. The cyst was punctured and drained with the help of a Veress needle. Hypertonic saline was injected into the cyst and left for 10 minutes before respiration. Next, a partial excision of the cyst wall closest to the liver capsule was performed, and the germinative membrane was removed intact. The cyst cavity was irrigated with scolicidal agent and inspected for bile leakage. In cases with visible bile leakage, intraoperative suturing or clipping was performed where feasible. A drainage catheter was placed into the cyst cavity before completing the operation.

All patients underwent US at 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-procedure and annually thereafter. On US evaluation, cyst volume, internal content, wall structure, calcification, and the presence of solid or semi-solid components were assessed. Recurrence was defined as the reappearance or interval enlargement of a cystic lesion with imaging features suggesting viable parasitic elements, such as newly formed or detached membranes, daughter cysts, or enhancing solid components, following an initial post-treatment reduction in size. Recollection, in contrast, referred to sterile fluid accumulation within the residual cavity without viable structures or parasitic membranes. This distinction is clinically important, as reco

All analyses were performed using SPSS software v. 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, United States: IBM Corp.). The variables were divided into two groups as categorical or continuous. Categorical variables were expressed as n (%) and compared with the χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to test normality and a P > 0.05 was considered to indicate normally distributed data. Continuous variables that showed normal distribution were compared using Student’s t test, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed samples. The statistical significance level was accepted as P < 0.05.

A total of 989 patients were included, with 74.2% (n = 734) undergoing surgical treatment and 25.8% (n = 255) receiving percutaneous treatment. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the surgical and percutaneous groups in terms of gender distribution (female: 76.0% vs 72.2%; P = 0.250) or age (38.4 ± 15.9 years vs 38.1 ± 16.1 years; P = 0.800). The majority of patients in both groups had a single cyst (74.7%, n = 548 vs 75.3%, n = 192; P = 0.850). The percutaneous group had a significantly higher proportion of cysts located in the right lobe (80.9% vs 70.6%;

| Variables | Surgical (n = 734) | Percutaneous (n = 255) | All patients | P value |

| Age (years) | 38.4 ± 15.9 | 38.1 ± 16.1 | 38.3 ± 16.0 | 0.801 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 176 (24.0) | 71 (27.8) | 247 (24.9) | 0.250 |

| Female | 558 (76.0) | 184 (72.2) | 742 (75.1) | |

| Number of cysts | ||||

| Single | 548 (74.7) | 192 (75.3) | 740 (74.8) | 0.850 |

| Two | 153 (20.9) | 49 (19.1) | 202 (20.4) | 0.450 |

| Multiple | 31 (4.2) | 14 (5.6) | 45 (4.6) | 0.350 |

| Location | ||||

| Right lobe | 518 (70.6) | 206 (80.9) | 724 (73.2) | 0.042a |

| Left lobe | 216 (29.4) | 49 (19.1) | 265 (26.8) | |

| Position | ||||

| Central | 292 (39.8) | 67 (26.4) | 359 (36.3) | 0.031a |

| Peripheral | 442 (60.2) | 188 (73.6) | 630 (63.7) | |

| Cyst type | ||||

| WHO CE1 | 479 (65.3) | 200 (78.6) | 679 (68.7) | 0.048a |

| WHO CE3a | 255 (34.7) | 55 (21.8) | 310 (31.3) | |

| Cyst longest diameter (mm) | 120.4 ± 47.8 | 118.2 ± 46.9 | 119.9 ± 47.6 | 0.620 |

| Initial volume (mL) | 421.1 ± 266.0 | 374.3 ± 295.2 | 410.0 ± 274.3 | 0.537 |

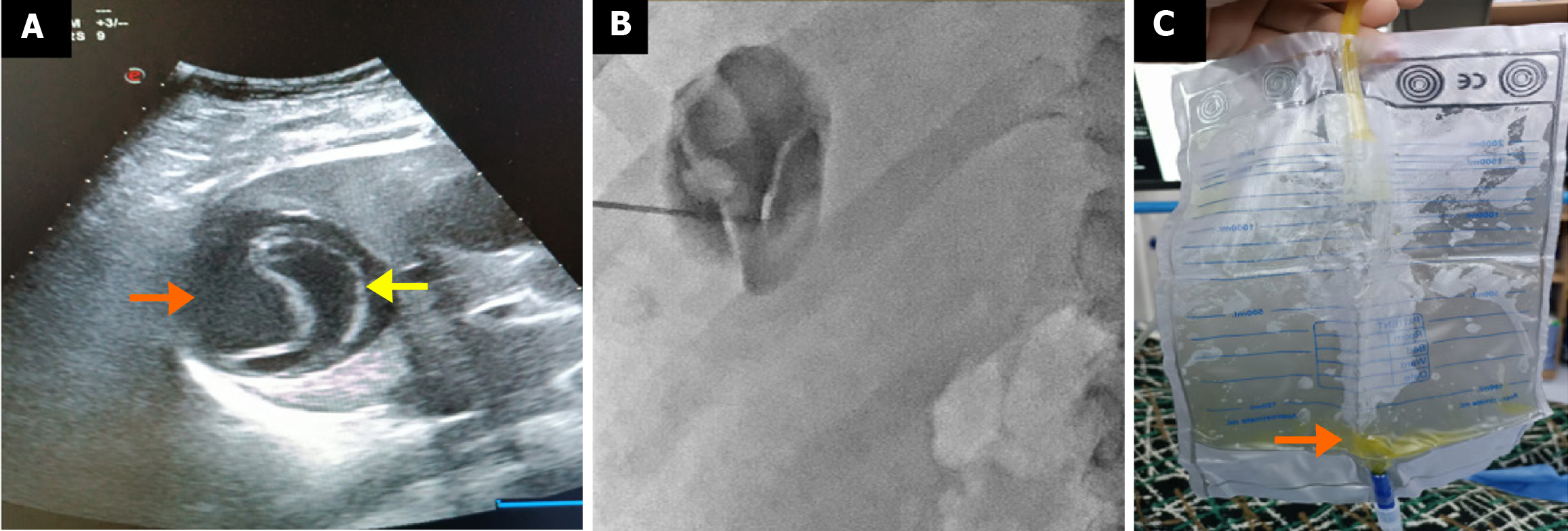

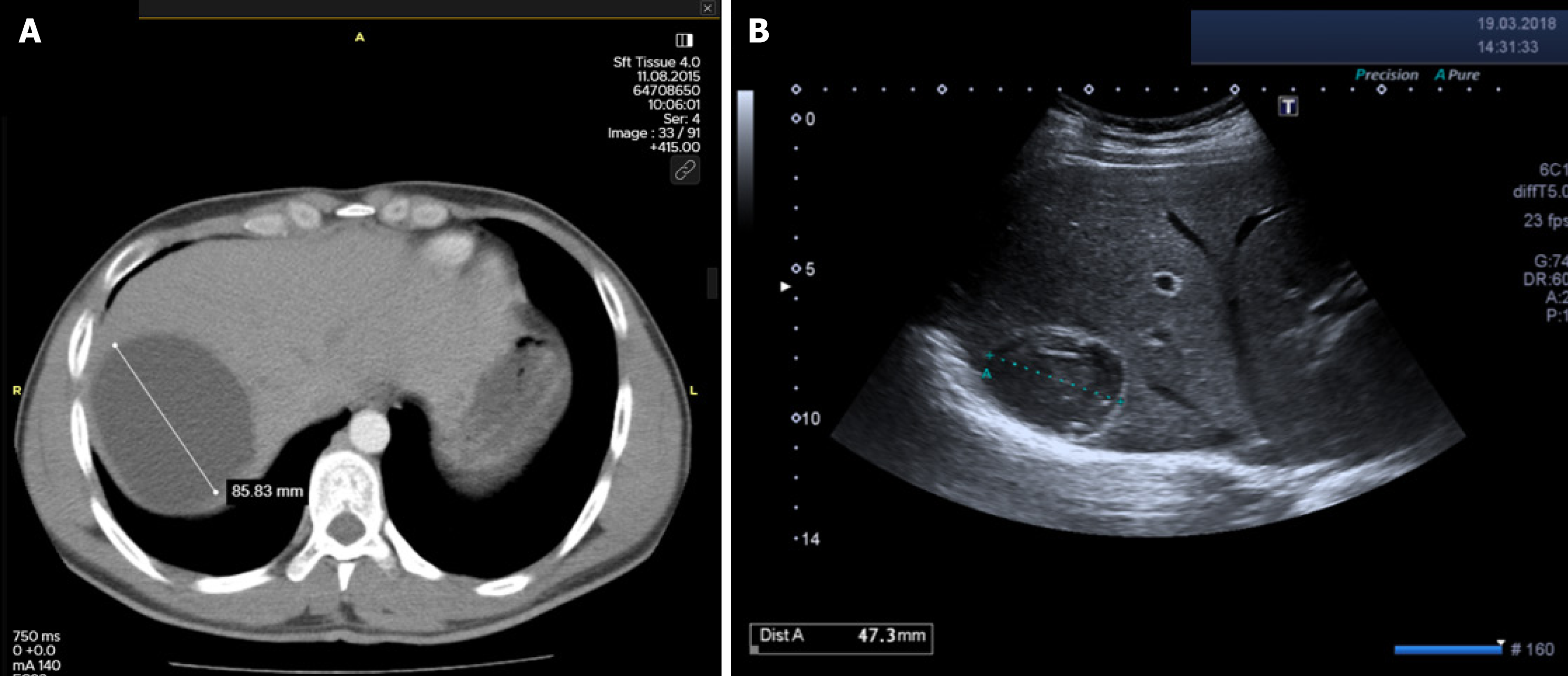

Table 2 summarizes the rates of major and minor complications according to treatment modality. The incidence of cystobiliary fistula (CBF) was comparable between the surgical and percutaneous groups (15.4% vs 16.8%; P = 0.651). However, recollection was significantly more frequent in the percutaneous group (4.7% vs 1.2%; P = 0.001), as was anaphylaxis (1.6% vs 0.3%; P = 0.041) (Figures 1 and 2). In contrast, true recurrence rates were low in both groups and did not differ significantly [surgical: 8/734 (1.1%) vs percutaneous: 4/255 (1.6%); P = 0.550]. Intraoperative organ injuries (diaphragm, liver, intestine) occurred in 2.7% of surgical patients (n = 20), but none were observed in the percutaneous group (P = 0.002). Minor complication rates were comparable between groups (23.4% vs 18.4%; P = 0.092). Postoperative pain was significantly more frequent in the surgical group (19.5% vs 11.0%; P = 0.002). Other minor complications such as fever, pleural effusion, and urticaria showed no significant differences between groups. Incisional or umbilical hernia occurred in 1.2% (n = 9) of surgical patients, while no hernias were observed in the percutaneous group (P = 0.067).

| Type of complication | Surgical (n = 734) | Percutaneous (n = 255) | P value |

| Major complication | 155 (21.1) | 63 (24.7) | 0.234 |

| Cystobiliary fistula | 113 (15.4) | 43 (16.8) | 0.651 |

| Isolated cystobiliary fistula | 107 (14.6) | 38 (14.9) | 0.880 |

| Fistula + infection | 6 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | 0.231 |

| Isolated cavity infection | 5 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0.342 |

| Recollection | 9 (1.23) | 12 (4.71) | 0.001a |

| Recurrence | 8 (1.09) | 4 (1.57) | 0.550 |

| Anaphylaxis | 2 (0.3) | 4 (1.6) | 0.041a |

| Intraoperative iatrogenic injury | 20 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.002a |

| Diaphragm | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Liver | 12 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Intestinal | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Minor complications | 172 (23.4) | 47 (18.4) | 0.092 |

| Pain | 143 (19.5) | 28 (11.0) | 0.002a |

| Fever | 27 (3.7) | 9 (3.5) | 0.891 |

| Pleural effusion | 27 (3.7) | 8 (3.1) | 0.690 |

| Urticaria | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.8) | 0.262 |

| Incisional/umbilical hernia | 9 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.067 |

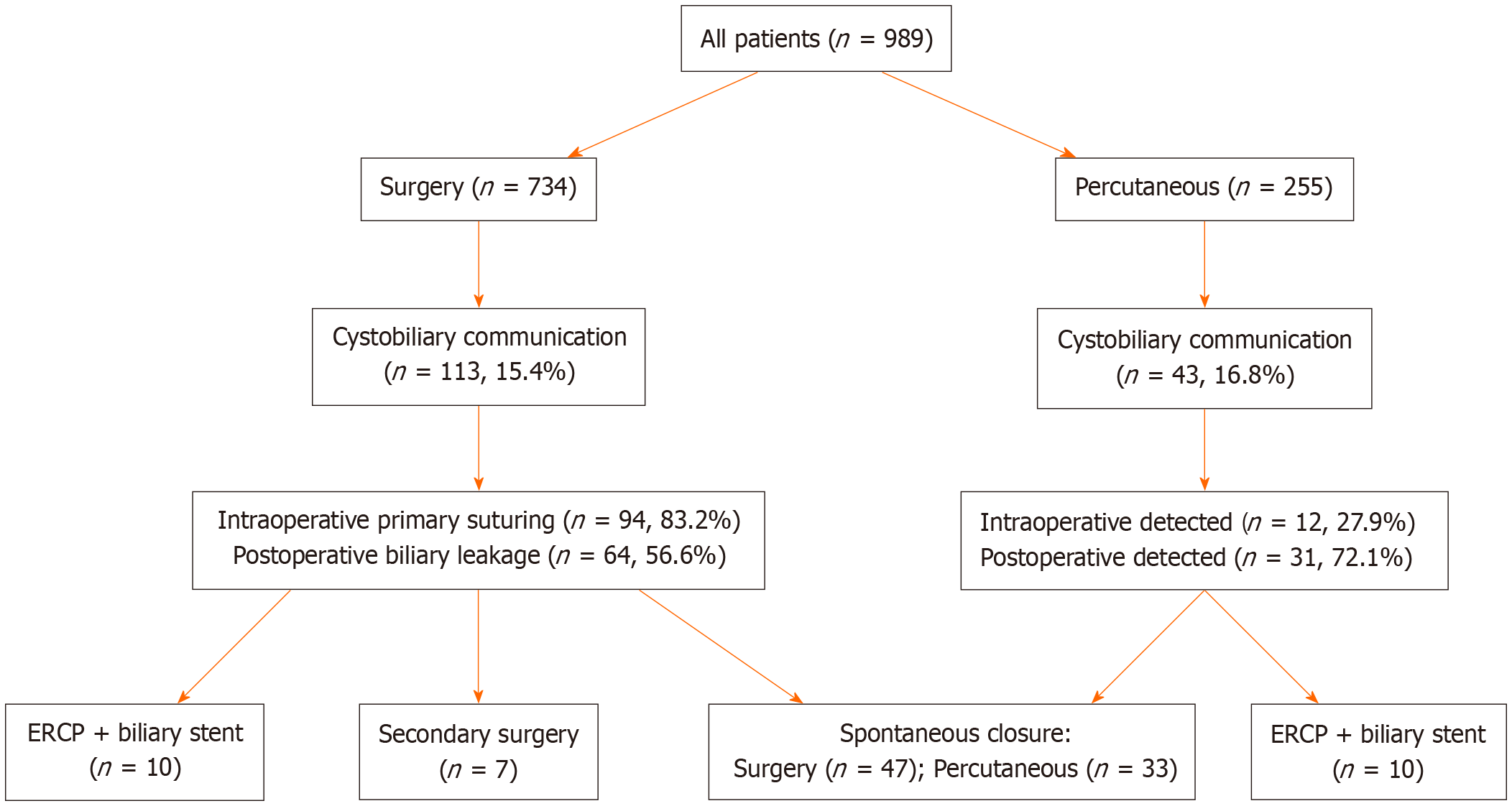

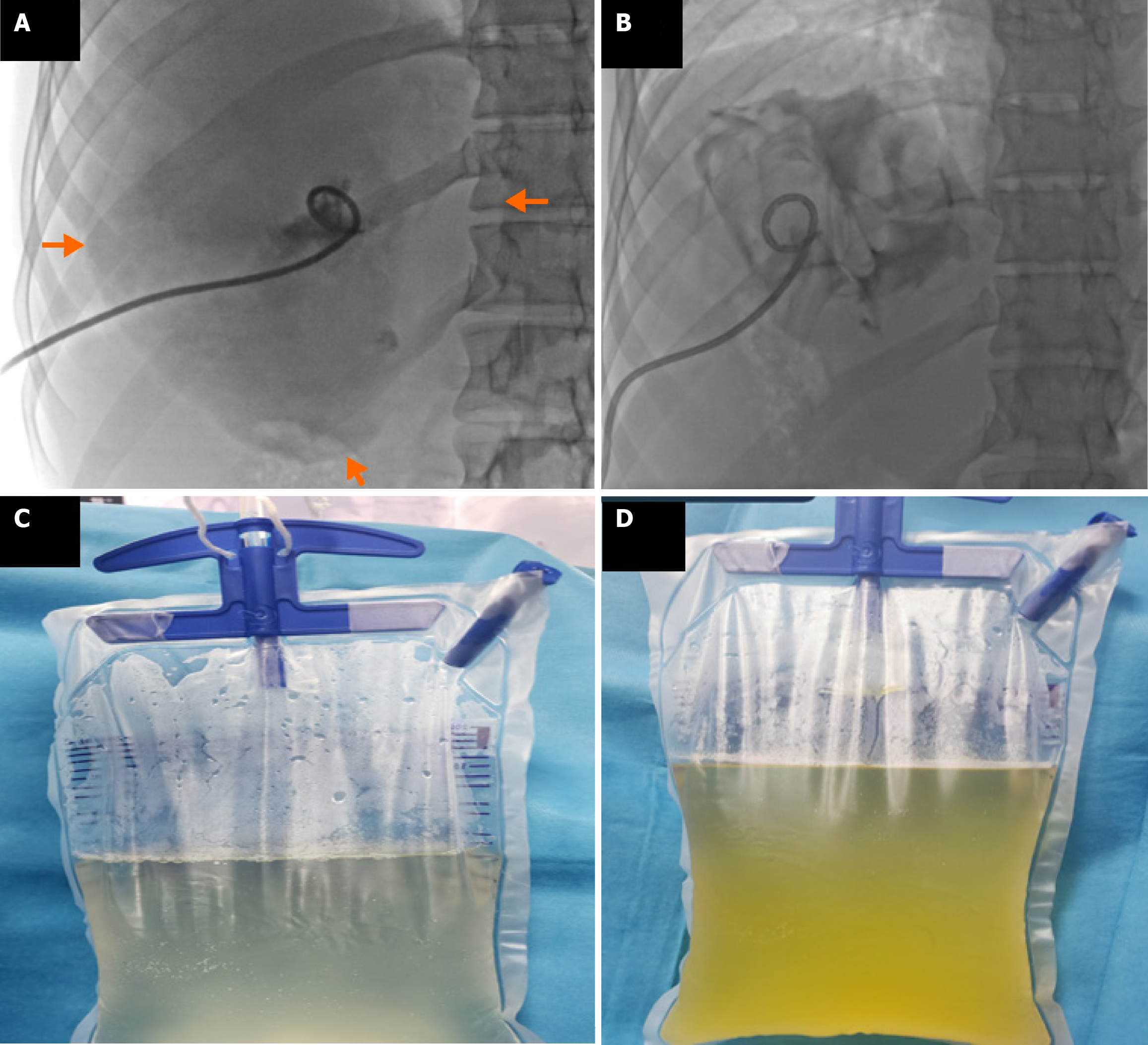

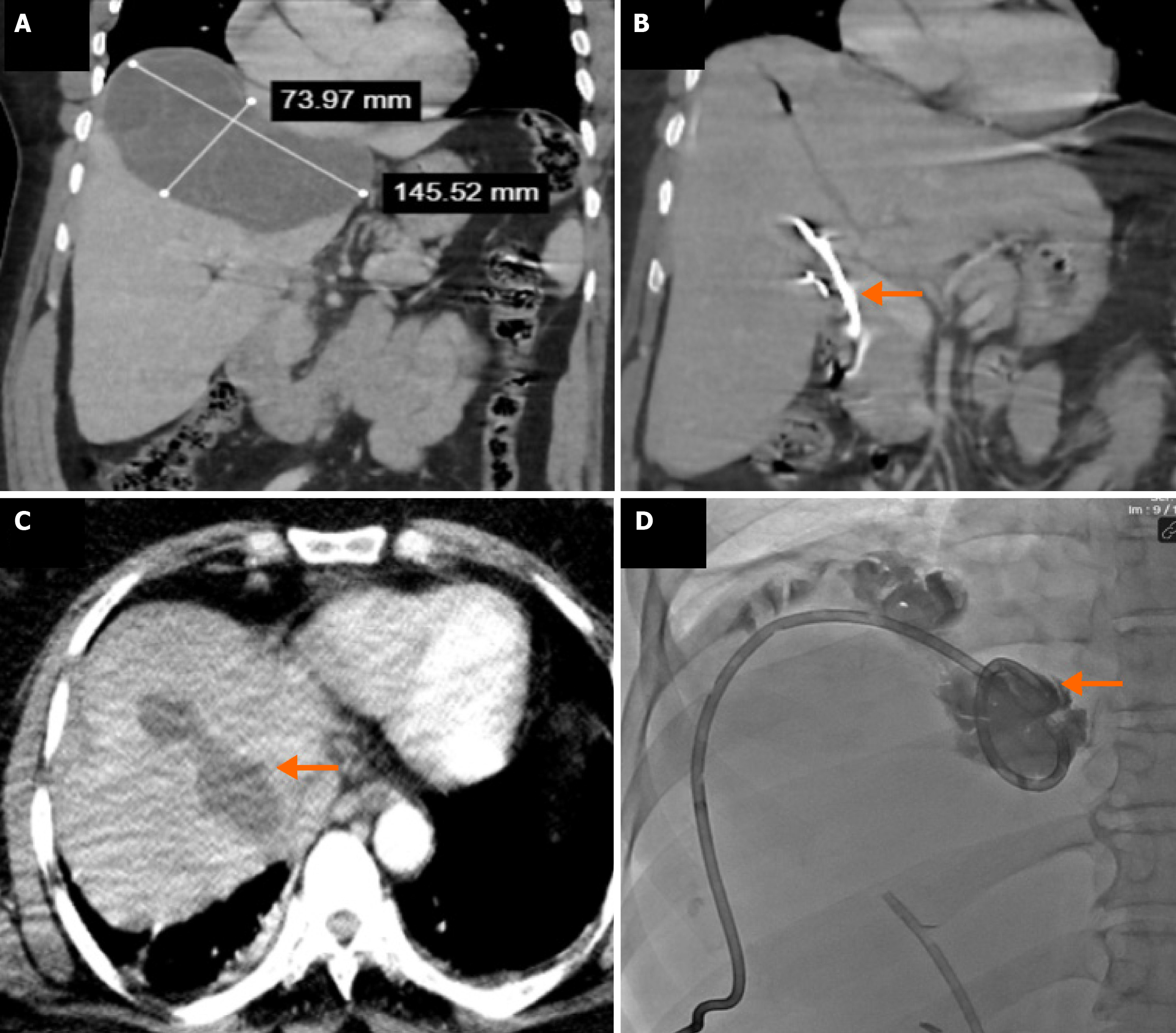

CBFs developed in 15.4% (n = 113/734) of surgically treated patients and 16.8% (n = 43/255) of percutaneously treated patients, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.651) (Table 3 and Figure 3). Intraoperative bile leakage was identified in 83.2% (n = 94) of surgical patients, with primary suture or clipping performed. Such interventions were not applicable in the percutaneous group (Figure 4). Post-procedural bile drainage via drains or catheters occurred more frequently in the percutaneous group (100% vs 56.6%; P < 0.001). The rate of spontaneous closure of the fistula without intervention was similar in both groups (76.7% vs 73.4%; P = 0.825). The mean time to spontaneous closure was also comparable between the surgical and percutaneous groups (14.2 ± 7.3 days vs 11.7 ± 9.4 days, respectively; P = 0.110). The need for postoperative ERCP due to persistent fistula was significantly higher in the percutaneous group (21.8% vs 8.8%; P = 0.033) (Figure 5). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of secondary surgical intervention (6.2% vs 4.6%, respectively; P = 1.000). In the surgical group, secondary surgery was required in 7 patients (6.2%) due to persistent fistulas. In the percutaneous group, two patients underwent secondary surgery by personal preference: One underwent left lobectomy and the other partial cystectomy.

| Variables | Surgical (n = 113) | Percutaneous (n = 43) | Total (n = 156) | P value |

| Cystobiliary fistula | 113/734 (15.4) | 43/255 (16.8) | 156/989 (15.8) | 0.651 |

| Intraoperative detection | 94/113 (83.2) | 12/43 (27.9) | 106/156 (67.9) | < 0.001a |

| Intraoperative primary suture | 94/113 (83.2) | 0/43 (0) | 94/156 (60.3) | |

| Postoperative bile drainage via catheter/drain | 64/113 (56.6) | 43/43 (100) | 107/156 (68.6) | < 0.001a |

| Spontaneous closure | 47/64 (73.4) | 33/43 (76.7) | 80/97 (82.4) | 0.825 |

| Secondary operation | 7/113 (6.2) | 2/43 (4.6) | 9/156 (5.8) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative ERCP | 10/113 (8.8) | 10/43 (21.8) | 20/156 (12.8) | 0.033a |

| Spontaneous closure time (days) | 14.2 ± 7.3 | 11.7 ± 9.4 | 13.0 ± 8.6 | 0.110 |

When all patients were considered, those who developed a fistula had significantly longer hospital stays (9.9 ± 5.3 days vs 5.4 ± 4.6 days, respectively; P < 0.001), prolonged catheter removal times (13.0 ± 8.9 days vs 4.5 ± 3.2 days, respectively; P < 0.001), and larger initial cyst volumes (726.8 ± 397.6 mL vs 351.1 ± 226.4 mL, respectively; P < 0.001) compared to those without fistulas (Table 4). When each treatment group was evaluated separately, hospital stay duration was significantly longer in patients with fistulas in both the surgical group (10.3 ± 5.7 days vs 6.7 ± 6.0 days, respectively; P = 0.002) and the percutaneous group (9.4 ± 4.9 days vs 2.7 ± 1.5 days, respectively; P < 0.001). Similarly, catheter removal time was also significantly prolonged in patients with fistulas in both groups (surgical: 8.3 ± 4.9 days vs 5.9 ± 2.7 days, respectively; P = 0.018 and percutaneous: 17.8 ± 8.7 days vs 3.5 ± 2.9 days, respectively; P < 0.001). Additionally, initial cyst volumes were significantly higher in the groups that developed fistulas. In the surgical group, the initial volume was 774.8 ± 513.2 mL in patients with fistulas and 356.7 ± 95.6 mL in those without (P < 0.001). In the percutaneous group, these values were 700.9 ± 288.2 mL and 346.5 ± 279.2 mL (P < 0.001).

| Parameter | Treatment group | Cystobiliary fistula (+) | Cystobiliary fistula (-) | P value |

| Hospital stay (days) | Surgical | 10.3 ± 5.7 | 6.7 ± 6.0 | 0.002a |

| Percutaneous | 9.4 ± 4.9 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | < 0.001a | |

| All patients | 9.9 ± 5.3 | 5.4 ± 4.6 | < 0.001a | |

| Catheter removal time (days) | Surgical | 8.3 ± 4.9 | 5.9 ± 2.7 | 0.018a |

| Percutaneous | 17.8 ± 8.7 | 3.5 ± 2.9 | < 0.001a | |

| All patients | 13.0 ± 8.9 | 4.5 ± 3.2 | < 0.001a | |

| Initial volume (mL) | Surgical | 774.8 ± 513.2 | 356.7 ± 95.6 | < 0.001a |

| Percutaneous | 700.9 ± 288.2 | 346.5 ± 279.2 | < 0.001a | |

| All patients | 726.8 ± 397.6 | 351.1 ± 226.4 | < 0.001a |

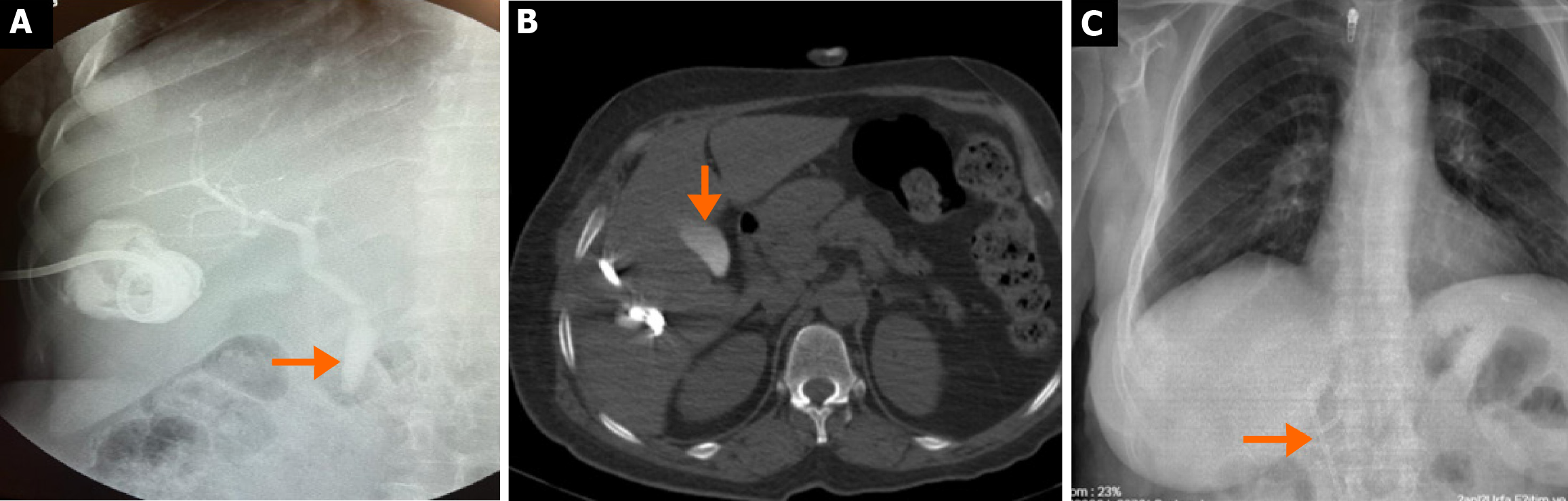

As shown in Table 5, during follow-up after treatment, the mean final cyst volume was significantly lower in the surgical group compared to the percutaneous group (46.9 ± 38.8 mL vs 63.3 ± 55.6 mL, respectively; P = 0.025), and the final volume reduction rate was statistically higher in the surgical group (88.9% vs 83.1%; P = 0.005) (Figure 6). The mean duration of follow-up imaging was significantly different between the groups, being 12.0 months (range: 3-60 months) in the surgical group and 18.6 months (range: 8-60 months) in the percutaneous group (P < 0.001). Hospital stay and catheter removal time were also significantly longer in the surgical group than in the percutaneous group (7.3 ± 6.2 days vs 3.1 ± 2.3 days, respectively; P < 0.001, and 6.6 ± 5.3 days vs 5.5 ± 6.4 days, respectively; P = 0.014). Among uncomplicated cases, the mean procedure duration was significantly longer in the surgical group [81.3 ± 27.6 minutes (range: 40-180 minutes) vs 40.4 ± 6.2 minutes (range: 30-60 minutes); P < 0.001]. In the surgical group, operation duration was considerably longer in patients who experienced complications (Table 5). Recurrence or recollection defined as symptomatic fluid accumulation in the cavity reaching initial volume levels was observed in 17 patients (2.3%) in the surgical group and 16 patients (6.3%) in the percutaneous group (P = 0.002). These patients underwent drainage or secondary surgery (Figure 7).

| Features | Surgical (n = 734) | Percutaneous (n = 255) | All patients | P value |

| Final volume of cyst (mL) | 46.9 ± 38.8 | 63.3 ± 55.6 | 53.5 ± 45.9 | 0.025a |

| Final reduction rate (%) | 88.9 | 83.1 | 86.6 | 0.005a |

| Follow-up imaging duration (months), median (IQR) | 12.0 (3.0-60.0) | 18.6 (8-60) | 13.7 (3-60) | < 0.001a |

| Hospital stay (days) | 7.3 ± 6.2 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 6.3 ± 5.8 | < 0.001a |

| Catheter removal time (days) | 6.6 ± 5.3 | 5.5 ± 6.4 | 6.3 ± 5.6 | 0.014a |

| Operation time without complications (minutes) | 81.3 ± 27.6 | 40.4 ± 6.2 | 70.6 ± 31.5 | < 0.001a |

| Operation time in patients with complications (minutes) | ||||

| Diaphragm injury (n = 6) | 163.3 ± 81.4 | |||

| Intestinal injury (n = 2) | 187.8 ± 53.1 | |||

| Liver injury (n = 12) | 115.6 ± 62.1 | |||

| Suturing and/or omentopexy in bile fistula | 103.1 ± 35.6 |

This study represents, to our knowledge, the largest comparative series from an endemic region evaluating surgical and percutaneous treatments for WHO CE1 and CE3a liver hydatid cysts, covering a 20-year period. While surgery has traditionally been the standard approach, percutaneous therapy has gained popularity in recent decades due to its minimally invasive nature, shorter hospital stays, and lower morbidity. However, large-scale comparative studies remain scarce. Previous studies by Khuroo et al[13], Tan et al[14], Abdelraouf et al[15], and Shera et al[16] included relatively small cohorts ranging from 40 to 102 patients. In contrast, our study provides robust data from a large patient population managed over two decades in an endemic region, encompassing both treatment approaches. Importantly, our analysis is limited to WHO CE1 and CE3a cysts, allowing for a more focused and clinically homogeneous evaluation. Consistent with earlier studies[13-16], we found that surgically treated patients experienced longer hospital stays (mean: 7.3 days vs 3.1 days), prolonged operative durations, and extended catheterization times. Based on these findings, percutaneous treatment appears to be a preferable approach for CE1 and CE3a cysts, offering reduced morbidity, lower healthcare costs, and a faster return to normal activities. Although the overall rate of major complications was similar between the groups (21.1% vs 24.7%), intraoperative organ injury involving the diaphragm, liver, or intestines occurred in 2.7% of surgical cases, underscoring the potential risks associated with operative management. A 2003 meta-analysis by Smego et al[17] which included 21 studies comprising 769 percutaneously and 952 surgically treated patients, reported higher rates of major complications such as cyst infection, intra-abdominal abscess, and biliary fistula in the surgical group, while the incidence of anaphylaxis was comparable between groups. In our study, similarly, cavity infections were more frequent among surgically treated patients, while biliary fistula rates were comparable. Notably, anaphylaxis and fluid recollection were observed more frequently in the percutaneous group.

Anaphylaxis is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication that can occur during the treatment of CE. A systematic review of 5943 patients reported a fatal anaphylaxis rate of 0.03%, and a reversible anaphylactic reaction rate of 1.7%[18]. In another study focused exclusively on patients with giant cysts treated percutaneously, the rate of reversible anaphylaxis was 4.5%[19]. In our cohort, anaphylaxis occurred more frequently in percu

In recent years, a modified form of the PAIR technique referred to as drainage, puncture, alcohol injection (DPAI) has been introduced, in which the instilled ethanol is not re-aspirated. Shera et al[16] have reported its feasibility in selected cases. However, we intentionally adhered to the conventional PAIR method with re-aspiration in order to reduce the risk of systemic absorption of ethanol and sclerosing cholangitis, particularly in cysts with a potential but undetected cys

In our study, CBF was present in a considerable proportion of patients in both treatment groups, with comparable rates (surgical: 15.4%, percutaneous: 16.8%). Cystobiliary communication remains one of the most significant challenges in the management of hepatic hydatid cysts, as it is associated with prolonged hospitalization, extended catheterization duration, and an increased risk of cavity infection. Previous studies on percutaneous treatment have reported highly variable CBF rates, ranging from 5% to 37%[20-23]. For instance, Aribas et al[20] reported an incidence of 11.1% (10/90), Atli et al[22] reported 21% (24/116), Unalp et al[23] reported 25% (64/252), and Kayaalp et al[21] reported 37% (45/121). In a surgical cohort, Chopra et al[24] documented a CBF incidence of 39.0% among 41 patients, with intraoperative identification and suturing performed in 28.9%. Several factors may account for the variability in CBF rates, including cyst characteristics (type, size, and location), fistula tract diameter (> 5 mm considered major; < 5 mm minor), the presence of frank vs occult fistulae, and the timing of detection. Pre-treatment pressure gradients also play a role. While the biliary system typically has a lower baseline pressure (15-20 cm water) compared to the cyst cavity (30-80 cm water), favoring bile flow toward the bile ducts, this gradient may reverse following percutaneous intervention, leading to bile leakage into the cyst cavity and clinical manifestation of a fistula[23,25]. One major advantage of surgery is the opportunity for intraoperative identification and direct suturing or clipping of the fistula. In our surgical cohort, 83.4% of CBF cases were identified and sutured intraoperatively. Similarly, Chopra et al[24] reported that 68.8% (11/16) of cases were managed surgically at the time of operation, while 18.7% (3/16) required ERCP due to persistent postoperative leakage. These findings suggest that intraoperative management may reduce the need for postoperative ERCP. In our study, ERCP was required significantly less often in the surgical group compared to the percutaneous group (8.8% vs 21.8%, P = 0.033). However, previous reports have indicated that up to 72% of CBFs resolve spontaneously within two months without the need for ERCP[20]. Aribas et al[20] suggested that for patients with daily bile drainage less than 206 mL, observation for up to three months may be appropriate. In our cohort, the mean time to spontaneous closure was similar between groups: 14.2 days in the surgical group and 11.7 days in the percutaneous group. Consistent with the literature, patients with CBF in both treatment arms experienced longer hospital stays, extended catheter duration, and larger initial cyst volumes compared to those without fistulae.

The effectiveness of percutaneous treatment in WHO CE1 and CE3a cysts has been well demonstrated, with clinical success rates ranging between 97.1% and 100%[26-29]. In our study, when patients who developed recurrence or recollection were excluded, clinical success was achieved in 97.7% of surgical cases and 93.3% of those treated percutaneously. Previous research has demonstrated recurrence rates of 6% in a cohort of 100 surgically treated patients[30], and as low as 1.7% in a combined series of 60 laparoscopic and 253 open surgical cases[31]. In contrast, other studies have reported recurrence rates ranging between 1.1% and 24%[32,33] reflecting substantial variability in outcomes. In our cohort, true recurrence occurred in 1.1% of surgically treated patients (8/734) and 1.6% of those treated percutaneously (4/255), while sterile recollection was observed in 1.2% and 4.7% of the respective groups (P = 0.001 for recollection). These findings suggest that recollection was significantly more frequent following percutaneous procedures, whereas recurrence rates were comparable between groups. In patients with CE, clinical success is typically defined by symptom resolution, absence of viable parasites, and lack of recurrence. The considerable variability in reported recurrence rates may be attributed to differences in definitions, diagnostic criteria, and interpretation between radiologists and surgeons. Notably, while “recurrence” and “recollection” are often used interchangeably in the literature, they actually denote different phenomena: Recurrence refers to disease reappearance with viable parasites, whereas recollection describes fluid accumulation without parasitic activity[6,7,33]. In our study, microbiological analysis of aspirated cyst fluid for viable protoscolices was not performed; thus, differentiation between the two was primarily based on imaging characteristics and clinical evolution. In a comparative study by Abdelraouf et al[15], which compared both treatment methods, the recurrence rate in the percutaneous group (n = 8/23, 34.8%) was higher than in the surgical group (n = 2/14, 14.3%), likely because cases of recollection were misclassified as recurrence. A systematic review by Gomez I Gavara et al[34] emphasized the role of omentoplasty, when combined with conservative surgery, in preventing postoperative fluid collection. This aligns with our findings, where a higher rate of recollection was observed among patients treated percutaneously. Based on these data, surgical treatment appears more favorable in minimizing recurrence or recollection. Moreover, although both modalities significantly reduced cyst volume during follow-up, volume reduction was more pronounced in the surgical group. It is important to note, however, that this reflects anatomical rather than clinical outcomes, as calcified or solidified cysts may still indicate successful therapy. The removal of the germinative membrane during surgery, particularly in larger cysts, may contribute to the greater final volume reduction observed in this group. It should be noted that the mean follow-up duration was significantly longer in the percutaneous group. This discrepancy may have led to an underestimation of late recurrence or recollection in the surgical group, representing a potential source of bias when comparing long-term outcomes.

In recent years, radical surgical approaches such as total cysto-pericystectomy and hepatectomy have been increasingly advocated as the definitive treatment for hepatic hydatid disease, particularly in large or centrally located cysts. These methods allow complete removal of the cyst and pericystic tissue, resulting in very low recurrence rates and are considered by some authors to be the treatment of first choice in experienced centers[35,36]. Subadventitial (closed) total pericystectomy, in particular, is proposed as the standard technique where feasible, as it enables complete restoration of liver parenchyma while preserving hepatic function[37]. However, these radical procedures require advanced surgical expertise, adequate instrumentation and are associated with higher intraoperative risk, especially in cysts located near major vascular or biliary structures. In our center, the majority of patients presented with WHO CE1 and CE3a cysts, which are morphologically suitable for conservative surgery or percutaneous treatment. Radical procedures were not routinely performed due to cyst proximity to critical vasculobiliary structures, limited surgical resources in some instances, and an institutional preference for parenchyma-sparing surgery. Therefore, our study focuses on conservative surgery vs percutaneous therapy, which reflects real-world practice in many endemic regions. This also highlights the need for future studies comparing percutaneous treatment with radical surgical procedures such as total pericystectomy or hepatectomy.

In our cohort, CE3a cysts and centrally located lesions in the left hepatic lobe were significantly more likely to be treated surgically[13,19]. This may reflect operator preference rather than absolute clinical necessity. Central location is often associated with a higher likelihood of cystobiliary communication and greater technical difficulty for safe per

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective evaluation of patient data based on medical records may have resulted in missing or incomplete information. Second, due to the inclusion of patients over a long time period, differences in operator experience, skills, techniques, and technological advancements may have influenced clinical outcomes and complication rates. Third, the study is limited to WHO CE1 and CE3a cyst types, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to other types such as CE2 and CE3b. Fourth, the absence of randomized patient allocation may have introduced selection bias. Fifth, the unequal follow-up durations between groups may have influenced recurrence estimates, potentially favoring the surgical group due to shorter observation time. Future studies should incorporate time-to-event analyses such as Kaplan-Meier curves to more accurately compare recurrence-free survival. Lastly, the lack of subgroup analysis for surgical techniques (laparoscopic vs open, or conventional vs radical) is also a limitation. Additionally, a potential selection bias may have occurred because CE3a and centrally located cysts, which are generally more complex and technically challenging, were more frequently treated surgically. This non-random allocation may have influenced the observed complication and recurrence rates between treatment groups. Additionally, no parasitological or microbiological examination of the cyst fluid was performed to confirm the presence of viable protoscoleces. Therefore, recurrence and recollection were defined solely based on imaging findings and clinical follow-up, which may limit the precision of recurrence classification. Furthermore, this study did not stratify surgical inter

From an internal validity perspective, the retrospective and non-randomized design, operator variability, and reliance on medical records may have introduced measurement and selection biases.

From an external validity perspective, the single-center nature, focus on only CE1 and CE3a cysts, and the endemic setting limit the generalizability of our results to other populations and cyst types.

To improve both internal and external validity, future studies should consider prospective, multicenter designs and randomized controlled trials including broader cyst types such as CE2 and CE3b. Additionally, standardized definitions of recurrence and recollection, along with uniform follow-up protocols, are essential for more accurate outcome comparisons.

Our study demonstrates that the percutaneous approach is a safe and effective treatment modality for WHO CE1 and CE3a hepatic cysts, offering advantages such as shorter hospital stay, minimal invasiveness, reduced operative time, and a very low risk of intraoperative organ injury. Both surgical and percutaneous methods achieve high clinical success rates; however, the surgical approach appears slightly more advantageous in terms of reducing the risks of recollection and anaphylaxis. A larger cyst volume is associated with an increased risk of fistula formation and prolonged treatment duration for both treatment modalities. Therefore, patient selection should be carefully guided by these parameters. However, it should be emphasized that radical surgery (e.g., total pericystectomy or hepatectomy) remains the gold standard in eligible patients, while percutaneous treatment offers a safe and practical alternative for selected CE1/CE3a cysts, particularly in resource-limited or high-risk surgical settings.

| 1. | Nunnari G, Pinzone MR, Gruttadauria S, Celesia BM, Madeddu G, Malaguarnera G, Pavone P, Cappellani A, Cacopardo B. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1448-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | WHO Informal Working Group. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003;85:253-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akhan O, Özbay Y, Ünal E, Karaagaoglu E, Çiftçi TT, Akıncı D. Long-Term Results of Modified Catheterization Technique in the Treatment of CE Type 2 and 3b Liver Hydatid Cysts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2025;48:503-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kern P, Menezes da Silva A, Akhan O, Müllhaupt B, Vizcaychipi KA, Budke C, Vuitton DA. The Echinococcoses: Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Burden of Disease. Adv Parasitol. 2017;96:259-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Akhan O, Salik AE, Ciftci T, Akinci D, Islim F, Akpinar B. Comparison of Long-Term Results of Percutaneous Treatment Techniques for Hepatic Cystic Echinococcosis Types 2 and 3b. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:878-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Akhan O, Gumus B, Akinci D, Karcaaltincaba M, Ozmen M. Diagnosis and percutaneous treatment of soft-tissue hydatid cysts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tamarozzi F, Akhan O, Cretu CM, Vutova K, Akinci D, Chipeva R, Ciftci T, Constantin CM, Fabiani M, Golemanov B, Janta D, Mihailescu P, Muhtarov M, Orsten S, Petrutescu M, Pezzotti P, Popa AC, Popa LG, Popa MI, Velev V, Siles-Lucas M, Brunetti E, Casulli A. Prevalence of abdominal cystic echinococcosis in rural Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey: a cross-sectional, ultrasound-based, population study from the HERACLES project. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:769-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akhan O, Yildiz AE, Akinci D, Yildiz BD, Ciftci T. Is the adjuvant albendazole treatment really needed with PAIR in the management of liver hydatid cysts? A prospective, randomized trial with short-term follow-up results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1568-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akhan O, Dincer A, Gököz A, Sayek I, Havlioglu S, Abbasoglu O, Eryilmaz M, Besim A, Baris I. Percutaneous treatment of abdominal hydatid cysts with hypertonic saline and alcohol. An experimental study in sheep. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Akhan O, Erdoğan E, Ciftci TT, Unal E, Karaağaoğlu E, Akinci D. Comparison of the Long-Term Results of Puncture, Aspiration, Injection and Re-aspiration (PAIR) and Catheterization Techniques for the Percutaneous Treatment of CE1 and CE3a Liver Hydatid Cysts: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:1034-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Balli O, Balli G, Cakir V, Gur S, Pekcevik R, Tavusbay C, Akhan O. Percutaneous Treatment of Giant Cystic Echinococcosis in Liver: Catheterization Technique in Patients with CE1 and CE3a. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:1153-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, Khan BA, Yattoo GN, Shah AH, Jeelani SG. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tan A, Yakut M, Kaymakçioğlu N, Ozerhan IH, Cetiner S, Akdeniz A. The results of surgical treatment and percutaneous drainage of hepatic hydatid disease. Int Surg. 1998;83:314-316. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Abdelraouf A, El-Aal AA, Shoeib EY, Attia SS, Hanafy NA, Hassani M, Shoman S. Clinical and serological outcomes with different surgical approaches for human hepatic hydatidosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:587-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shera TA, Choh NA, Gojwari TA, Shera FA, Shaheen FA, Wani GM, Robbani I, Chowdri NA, Shah AH. A comparison of imaging guided double percutaneous aspiration injection and surgery in the treatment of cystic echinococcosis of liver. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:20160640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smego RA Jr, Bhatti S, Khaliq AA, Beg MA. Percutaneous aspiration-injection-reaspiration drainage plus albendazole or mebendazole for hepatic cystic echinococcosis: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1073-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Neumayr A, Troia G, de Bernardis C, Tamarozzi F, Goblirsch S, Piccoli L, Hatz C, Filice C, Brunetti E. Justified concern or exaggerated fear: the risk of anaphylaxis in percutaneous treatment of cystic echinococcosis-a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Kaya V, Tahtabasi M, Konukoglu O, Yalcin M. Percutaneous Treatment of Giant Hydatid Cysts and Cystobiliary Fistula Management. Acad Radiol. 2023;30 Suppl 1:S132-S142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aribas BK, Arda K, Aribas O, Ciledag N, Yildirim E, Kavak S, Cosar Y, Tekin E. Percutaneous Management of Cystobiliary Fistulas by Small Catheters. Iran J Radiol. 2016;14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kayaalp C, Bostanci B, Yol S, Akoglu M. Distribution of hydatid cysts into the liver with reference to cystobiliary communications and cavity-related complications. Am J Surg. 2003;185:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Atli M, Kama NA, Yuksek YN, Doganay M, Gozalan U, Kologlu M, Daglar G. Intrabiliary rupture of a hepatic hydatid cyst: associated clinical factors and proper management. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1249-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Unalp HR, Baydar B, Kamer E, Yilmaz Y, Issever H, Tarcan E. Asymptomatic occult cysto-biliary communication without bile into cavity of the liver hydatid cyst: a pitfall in conservative surgery. Int J Surg. 2009;7:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chopra N, Gupta V; Rahul, Kumar S, Joshi P, Gupta V, Chandra A. Liver hydatid cyst with cystobiliary communication: Laparoscopic surgery remains an effective option. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14:230-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yalin R, Aktan AO, Yeğen C, Döşlüoğlu HH. Significance of intracystic pressure in abdominal hydatid disease. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1182-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Köroğlu M, Erol B, Gürses C, Türkbey B, Baş CY, Alparslan AŞ, Köroğlu BK, Toslak İE, Çekiç B, Akhan O. Hepatic cystic echinococcosis: percutaneous treatment as an outpatient procedure. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:212-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Akhan O, Ozmen MN. Percutaneous treatment of liver hydatid cysts. Eur J Radiol. 1999;32:76-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kabaalioğlu A, Ceken K, Alimoglu E, Apaydin A. Percutaneous imaging-guided treatment of hydatid liver cysts: do long-term results make it a first choice? Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kahriman G, Ozcan N, Donmez H. Hydatid cysts of the liver in children: percutaneous treatment with ultrasound follow-up. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:890-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Faraj W, Abi Faraj C, Kanso M, Nassar H, Hoteit L, Farsakoury R, Zaghal A, Yaghi M, Jaafar RF, Khalife M. Hydatid Disease of the Liver in the Middle East: A Single Center Experience. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2022;23:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tuxun T, Aji T, Tai QW, Zhang JH, Zhao JM, Cao J, Li T, Shao YM, Abudurexiti M, Ma HZ, Wen H. Conventional versus laparoscopic surgery for hepatic hydatidosis: a 6-year single-center experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1155-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Alzoubi M, Daradkeh S, Daradka K, Shattarat LN, Al-Zyoud A, Al-Qalqili LA, Al-Warafi WA, Al-Nezaa I, ElMoubarek MN, Qtaishat L, Rawashdeh B, Alhajahjeh A. The recurrence rate after primary resection cystic echinococcosis: A meta-analysis and systematic literature review. Asian J Surg. 2024;S1015-9584(24)02081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tarim I, Mutlu V, Karabulut K, Bircan R, Derebey M, Kamali Polat A, Erzurumlu K. Recurrence of Hepatic Hydatidosis: How and Why? Middle Black Sea J Health Sci. 2021;7:186-191. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Gomez I Gavara C, López-Andújar R, Belda Ibáñez T, Ramia Ángel JM, Moya Herraiz Á, Orbis Castellanos F, Pareja Ibars E, San Juan Rodríguez F. Review of the treatment of liver hydatid cysts. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Mohkam K, Belkhir L, Wallon M, Darnis B, Peyron F, Ducerf C, Gigot JF, Mabrut JY. Surgical management of liver hydatid disease: subadventitial cystectomy versus resection of the protruding dome. World J Surg. 2014;38:2113-2121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Goja S, Saha SK, Yadav SK, Tiwari A, Soin AS. Surgical approaches to hepatic hydatidosis ranging from partial cystectomy to liver transplantation. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pavlidis ET, Symeonidis NG, Psarras KK, Martzivanou EK, Marneri AG, Stavrati KE, Pavlidis TE. Total cysto-pericystectomy for huge echinococcal cyst located on hepatic segment IVb. Case report and review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;2021:rjab002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | WHO guidelines for the treatment of patients with cystic echinococcosis [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Öztürk G, Uzun MA, Özkan ÖF, Kayaalp C, Tatlı F, Eren S, Aksungur N, Çoker A, Bostancı EB, Öter V, Kaya E, Taşar P. Turkish HPB Surgery Association consensus report on hepatic cystic Echinococcosis (HCE). Turk J Surg. 2022;38:101-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Khuroo MS. Percutaneous Drainage in Hepatic Hydatidosis-The PAIR Technique: Concept, Technique, and Results. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11:592-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/