Published online Jan 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.115098

Revised: November 9, 2025

Accepted: November 19, 2025

Published online: January 7, 2026

Processing time: 89 Days and 15.2 Hours

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) has emerged as the preferred approach for both benign and malignant lesions located in the pancreatic body and tail. Ne

To establish procedure-specific criteria for TO and identify independent predi

Consecutive patients who underwent LDP at a single high-volume pancreatic center between January 2015 and August 2022 were retrospectively analyzed. TO was defined as the absence of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade B/C), post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (grade B/C), severe complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III), readmission within 30 days, and in-hospital or 30-day mortality. Multivariable logistic regression was employed to identify independent predictors of TO failure, and a nomogram was constructed and internally validated.

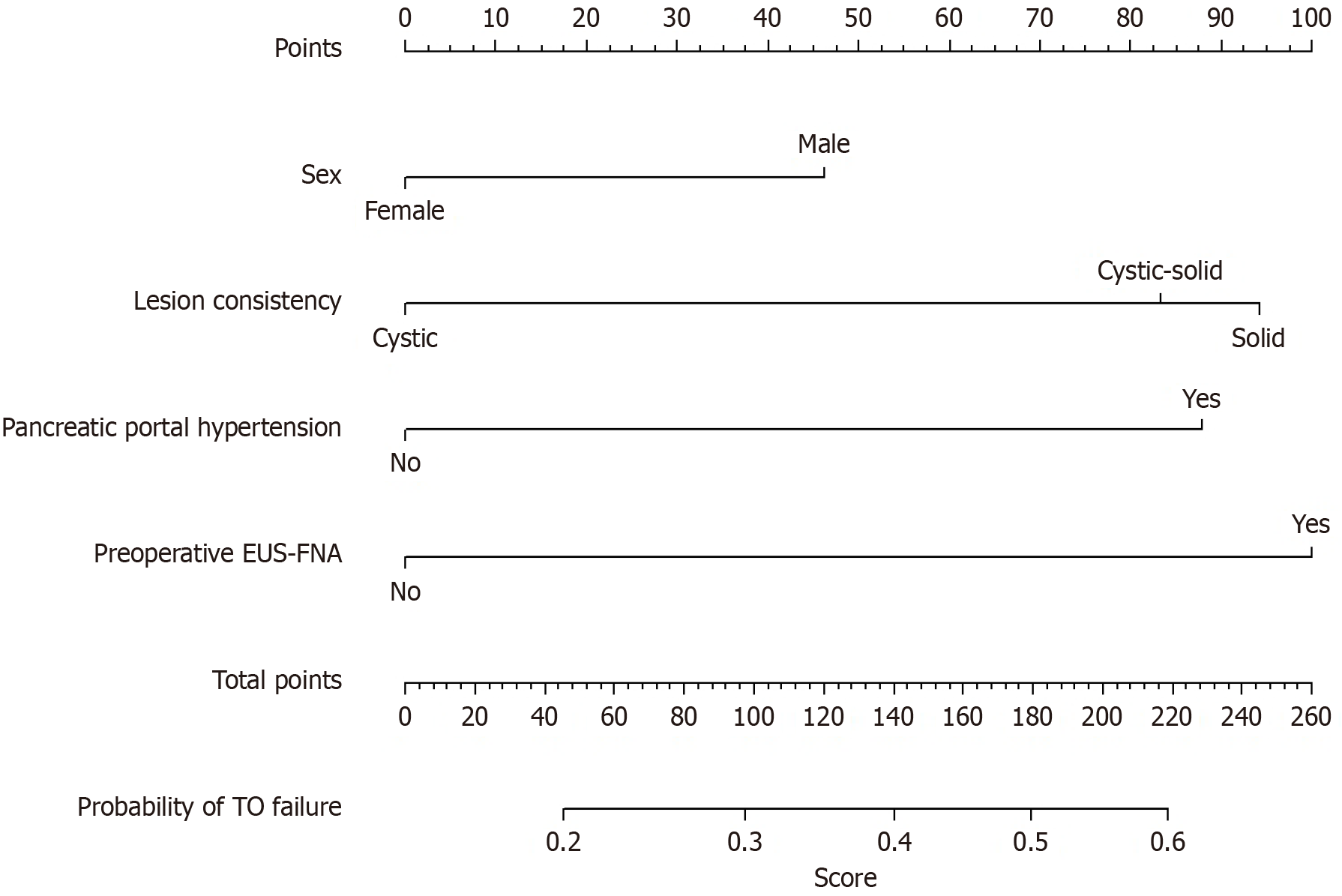

Among 405 eligible patients, 286 (70.6%) attained TO. Multivariable analysis revealed that female sex [odds ratio (OR) = 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.39-0.99] conferred a protective effect, while preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (OR = 2.66, 95%CI: 1.05-6.73), pancreatic portal hypertension (OR = 2.81, 95%CI: 1.06-7.45), and cystic-solid (OR = 2.51, 95%CI: 1.34-4.69) or solid lesions (OR = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.06-3.44) were independently associated with TO failure (all P < 0.05). The derived nomogram exhibited modest discrimination and calibration when assessed in both the training and validation datasets.

The proposed LDP-specific definition of TO is feasible and discriminative, and the developed nomogram provides an objective tool for individualized risk assessment.

Core Tip: We established a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy-specific textbook outcome composite absence of grade B/C postoperative pancreatic fistula, grade B/C post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage, Clavien-Dindo ≥ III morbidity, 30-day readmission, and in-hospital or 30-day mortality as a standardized quality indicator for distal pancreatic resection. Among 405 consecutive patients, textbook outcome was attained in 70.6%; female sex enhanced achievement, whereas pre-operative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration, pancreatic portal hypertension, and cystic-solid/solid pathology predicted failure. An internally validated nomogram is provided for individual pre-operative risk counselling.

- Citation: Huang XR, Zhu DS, Guo XY, Zhang JZ, Zhang Z, Zheng H, Guo T, Yu YH, Zhang ZW. Defining and predicting textbook outcomes in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(1): 115098

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i1/115098.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.115098

Minimally invasive surgery has progressed to the extent where laparoscopy has established itself as the standard approach for pancreatic interventions, including laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP)[1]. LDP presents numerous advantages over traditional open surgery, such as obviating the necessity for biliary-pancreatic-enteric reconstruction, simplifying operative procedures, and offering benefits such as reduced incision size, diminished blood loss, decreased occurrences of delayed gastric emptying, shorter hospitalization durations, and lower overall costs while upholding comparable long-term oncologic outcomes[2-4]. Consequently, LDP has evolved into a standard practice for both benign conditions (e.g., trauma, chronic pancreatitis, cystadenoma) and malignant lesions (e.g., ductal adenocarcinoma) affecting the pancreatic body and tail in high-volume centers worldwide[5,6].

Despite these advancements, LDP remains a technically demanding procedure with significant perioperative risks. The pancreas is situated deep within the retroperitoneum, encircled by critical structures such as the portal vein, superior mesenteric vessels, splenic vessels, stomach, colon, and spleen, which constrains the operative field[7]. The gland itself is delicate and prone to damage, with pancreatic juice possessing high corrosive properties, making even minor paren

While traditional quality metrics such as mortality, major morbidity, and length of stay (LOS) are easily measurable, they do not offer a comprehensive evaluation of perioperative quality[10,11]. Composite indicators such as “textbook outcome (TO)” are now considered as more effective than individual endpoints for assessing surgical quality. Initially introduced by Kolfschoten et al[12] in 2013 for colorectal surgery, TO represents an “all-or-none” composite measure[13] encompassing the absence of major complications, reoperation, readmission, prolonged hospitalization, and 30-day mortality. Since its inception, TO has been widely adopted in gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, and pancreatic surgery as a sensitive discriminator between institutions and a practical tool for enhancing quality[14-17].

In 2020, the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group (DPCG) proposed the initial definition of TO for pancreatic surgery in a nationwide study involving 3341 pancreatoduodenectomies (PD) and distal pancreatectomies (DP)[18]. Subsequent researches have demonstrated that TO standardizes quality assessment, identifies modifiable determinants of an “ideal” clinical course, and reduces resource utilization[19,20]. Nonetheless, the majority of TO investigations in pancreatic sur

This study aims to fill this research void by investigating the occurrence of TO in LDP, identifying its independent predictors, and constructing a visual risk prediction model using data from a single-center, prospectively maintained database. The results offer an evidence-based quality assessment tool for minimally invasive pancreatic surgery, advocate for the standardization of LDP procedures, expedite recovery, reduce healthcare expenses, and contribute Chinese data to future international guidelines. Through these efforts, we aspire to enhance the comprehension and implementation of TO in LDP, ultimately improving patient outcomes and surgical quality.

This retrospective single-center study was carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. TJ-IRB202407020). Sequential patients who underwent LDP between January 1, 2015, and August 31, 2022, were identified from our prospectively maintained pancreatic surgery database. Essential missing variables were obtained from the electronic medical records and the picture archiving and communication system.

Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) Cases of diagnostic laparoscopy or biopsy solely, or those converted to open surgery (n = 45); (2) Prior pancreatic operation requiring redo LDP (n = 8); and (3) Incomplete assessment of any TO component (n = 59). The final analysis included a cohort of 405 patients.

All procedures were performed by three senior surgical teams, each of which had surpassed the learning curve for LDP. Preoperative indications were assessed by a multidisciplinary team: Patients were considered eligible if they had benign or malignant lesions confined to the pancreatic body or tail, no involvement of the celiac axis or superior mesen

Pancreas-specific morbidities, namely post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) and postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), were categorized according to the 2007 and 2016 criteria of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery[23,24], respectively. Other complications were classified using Clavien-Dindo grading system[25], with a grade of III or higher considered severe complications.

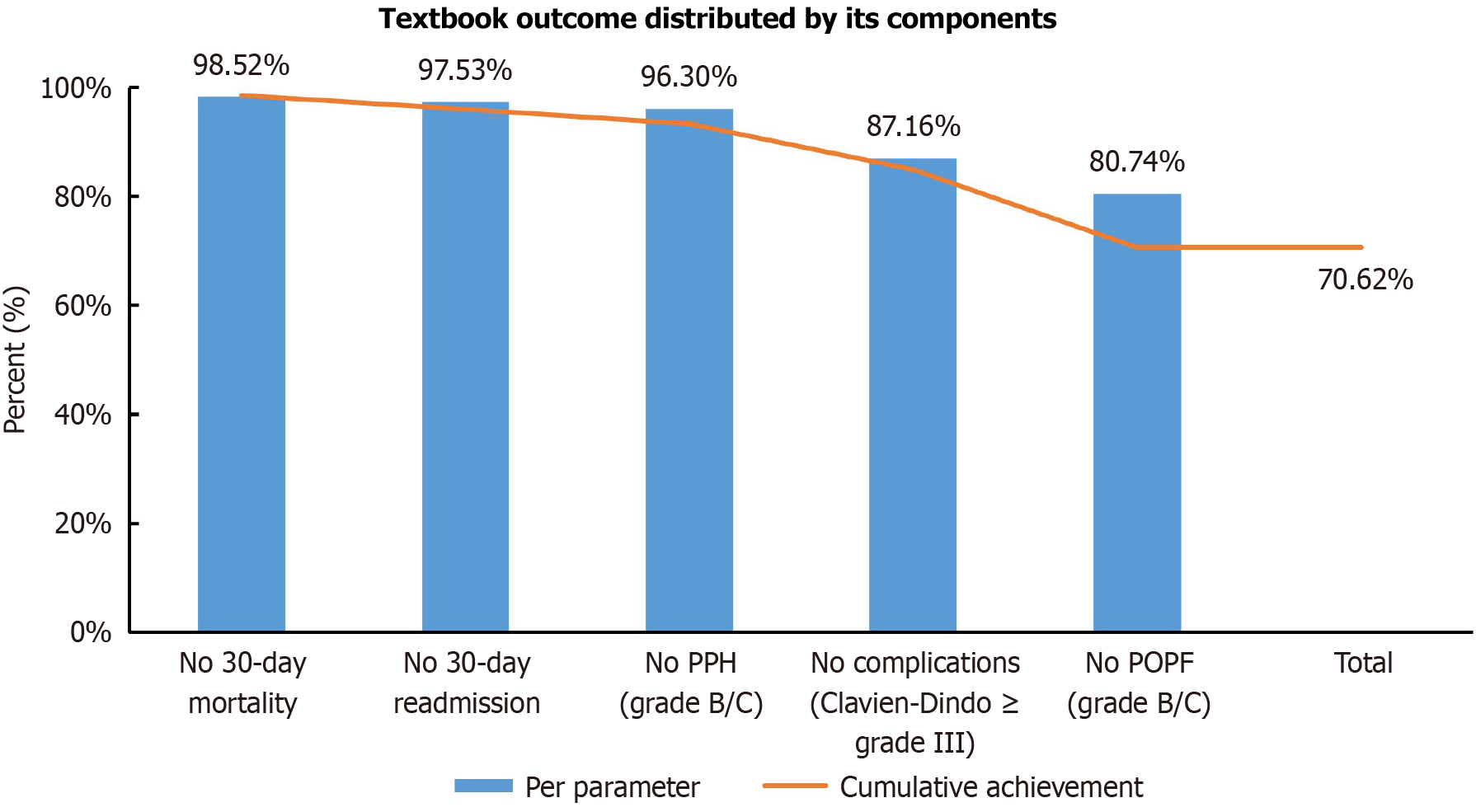

In LDP, TO was defined as the simultaneous satisfaction of the following criteria: (1) Absence of POPF (grade B/C); (2) Absence of PPH (grade B/C); (3) Absence of severe complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III); (4) No readmission within 30 days after discharge; and (5) No in-hospital or 30-day mortality[18].

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.1, R Core Team, 2024). A two-sided P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD and compared between groups using the independent-samples Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as median (25th, 75th percentiles) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are described as n (%) and compared using Pearson’s χ2 test, continuity-corrected χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test, depending on expected cell frequencies. Univariable screening (P < 0.05) was followed by multivariable logistic regression, with backward elimination used to retain variables that minimized the Akaike information criterion. The dataset was randomly divided into a training set and a validation set in a 7:3 ratio. The risk-prediction model was de

The baseline characteristics of the 405 patients who underwent LDP are summarized in Table 1. Patients who achieved TO were significantly younger, more often female, and exhibited lower body mass index and fewer cardiovascular comorbidity compared to the TO-failure group (all P < 0.05). Significant differences were also observed in lesion-related factors: The TO cohort had fewer cystic-solid and solid lesions, a lower incidence of pancreatic portal hypertension, decreased involvement of splenic vessels, lower rates of local invasion, and less frequent preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) utilization (all P < 0.05). Intraoperatively, cases meeting TO criteria displayed shorter anesthesia and operative durations, along with a higher rate of spleen preservation.

| Variables | Total (n = 405) | TO (n = 286) | TO failure (n = 119) | P value |

| Age (years), median IQR | 51.0 (39.0-60.0) | 50.0 (37.0-58.0) | 53.0 (42.0-61.0) | 0.025a |

| Sex | 0.004a | |||

| Female | 245 (60.5) | 186 (65) | 59 (49.6) | |

| Male | 160 (39.5) | 100 (35) | 60 (50.4) | |

| BMI, median IQR | 22.5 (20.3-24.7) | 22.3 (20.0-24.3) | 23.2 (20.7-25.1) | 0.045a |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 31 (7.7) | 20 (7) | 11 (9.2) | 0.438 |

| Diabetes | 25 (6.2) | 20 (7) | 5 (4.2) | 0.288 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 57 (14.1) | 33 (11.5) | 24 (20.2) | 0.023a |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 34 (8.4) | 25 (8.7) | 9 (7.6) | 0.697 |

| Asymptomatic | 170 (42) | 123 (43) | 47 (39.5) | 0.514 |

| Weight loss | 56 (13.8) | 34 (11.9) | 22 (18.5) | 0.080 |

| ASA score | 0.425 | |||

| I | 64 (15.8) | 49 (17.1) | 15 (12.6) | |

| II | 279 (68.9) | 196 (68.5) | 83 (69.7) | |

| III | 62 (15.3) | 41 (14.3) | 21 (17.6) | |

| Lesion size (cm), median IQR | 3.5 (2.2-5.2) | 3.4 (2.1-5.0) | 3.7 (2.5-5.4) | 0.063 |

| Lesion location | 0.514 | |||

| Body | 189 (46.7) | 136 (47.6) | 53 (44.5) | |

| Neck | 45 (11.1) | 34 (11.9) | 11 (9.2) | |

| Tail | 171 (42.2) | 116 (40.6) | 55 (46.2) | |

| Pancreatic duct dilation | 73 (18) | 55 (19.2) | 18 (15.1) | 0.328 |

| Lesion consistency | < 0.001a | |||

| Cystic | 142 (35.1) | 117 (40.9) | 25 (21) | |

| Cystic-solid | 101 (24.9) | 65 (22.7) | 36 (30.3) | |

| Solid | 162 (40) | 104 (36.4) | 58 (48.7) | |

| Pancreatitis | 30 (7.4) | 19 (6.6) | 11 (9.2) | 0.363 |

| Pancreatic portal hypertension | 27 (6.7) | 13 (4.5) | 14 (11.8) | 0.008a |

| Splenic vessel involvement | 56 (13.8) | 33 (11.5) | 23 (19.3) | 0.039a |

| Preoperative EUS-FNA | 21 (5.2) | 10 (3.5) | 11 (9.2) | 0.017a |

| Pancreatic texture | 0.746 | |||

| Hard | 58 (14.3) | 42 (14.7) | 16 (13.4) | |

| Soft | 347 (85.7) | 244 (85.3) | 103 (86.6) | |

| Local invasion | 18 (4.4) | 8 (2.8) | 10 (8.4) | 0.013a |

| Anesthesia time (minute), median IQR | 212.0 (180.0-255.0) | 206.0 (174.0-245.0) | 221.0 (191.0-285.5) | < 0.001a |

| Operation time (minute), median IQR | 180.0 (150.0-225.0) | 178.0 (142.0-210.0) | 189.0 (160.0-245.5) | 0.005a |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL), median IQR | 100.0 (50.0-100.0) | 100.0 (50.0-100.0) | 100.0 (50.0-175.0) | 0.055 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 16 (4) | 10 (3.5) | 6 (5) | 0.467 |

| Spleen preservation | 179 (44.2) | 139 (48.6) | 40 (33.6) | 0.006 |

| Additional organ resection | 4 (1) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.7) | 0.363 |

| Lymph node dissection | 182 (44.9) | 121 (42.3) | 61 (51.3) | 0.099 |

| Malignancy | 86 (21.2) | 54 (18.9) | 32 (26.9) | 0.073 |

| Histological diagnoses | 0.033a | |||

| CP/PPC | 34 (8.4) | 22 (7.7) | 12 (10.1) | |

| Cyst | 13 (3.2) | 10 (3.5) | 3 (2.5) | |

| IPMN | 20 (4.9) | 18 (6.3) | 2 (1.7) | |

| MCN | 43 (10.6) | 33 (11.5) | 10 (8.4) | |

| NET/NEC | 45 (11.1) | 29 (10.1) | 16 (13.4) | |

| PDAC | 67 (16.5) | 37 (12.9) | 30 (25.2) | |

| SCN | 110 (27.2) | 86 (30.1) | 24 (20.2) | |

| SPN | 60 (14.8) | 42 (14.7) | 18 (15.1) | |

| Other | 13 (3.2) | 9 (3.1) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Margin | 1 | |||

| R0 | 400 (98.8) | 282 (98.6) | 118 (99.2) | |

| R1 | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 23 (5.7) | 12 (4.2) | 11 (9.2) | 0.046a |

Overall, 286 of 405 patients (70.6%) achieved TO. Figure 1 illustrates the achievement rates for each TO component: The most commonly met criterion was the absence of in-hospital or 30-day mortality (98.5%), followed by no 30-day readmission (97.5%), absence of grade B/C PPH (96.3%), and no severe complications (87.2%). POPF of grade B/C was the least frequently avoided (80.7%), emerging as the primary challenge in achieving TO.

Univariate analysis identified sex, cardiovascular disease, lesion consistency, splenic-vessel involvement, pancreatic portal hypertension, preoperative EUS-FNA, local invasion, and spleen preservation as factors associated with TO. Mul

| Variables | Univariable OR (95%CI) | P value | Multivariable OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 1.44 (0.93-2.22) | 0.100 | ||

| Sex: Female | 0.53 (0.34-0.82) | 0.004a | 0.62 (0.39-0.99) | 0.046a |

| BMI grade | ||||

| 18.5-24 | Ref. | |||

| < 18.5 | 0.84 (0.39-1.81) | 0.658 | ||

| ≥ 24 | 1.50 (0.94-2.39) | 0.088 | ||

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 1.35 (0.63-2.92) | 0.439 | ||

| Alcohol | 1.55 (0.68-3.52) | 0.297 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.58 (0.21-1.59) | 0.293 | ||

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.85 (0.39-1.89) | 0.697 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 0.87 (0.56-1.34) | 0.514 | ||

| Anemia | 1.24 (0.66-2.31) | 0.508 | ||

| Weight loss | 1.68 (0.94-3.02) | 0.082 | ||

| ASA score | ||||

| I and II | Ref. | |||

| III and IV | 1.28 (0.72-2.28) | 0.400 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.94 (1.09-3.45) | 0.025 | 1.62 (0.88-2.98) | 0.117 |

| Pancreatitis | 1.43 (0.66-3.11) | 0.365 | ||

| Lesion size (cm) | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | 0.078 | ||

| Lesion location | ||||

| Tail | Ref. | |||

| Body | 0.82 (0.52-1.29) | 0.394 | ||

| Neck | 0.68 (0.32-1.45) | 0.319 | ||

| Lesion consistency | ||||

| Cystic | Ref. | |||

| Cystic-solid | 2.59 (1.43-4.69) | 0.002a | 2.51 (1.34-4.69) | 0.004a |

| Solid | 2.61 (1.52-4.47) | < 0.001a | 1.91 (1.06-3.44) | 0.032a |

| Splenic vessel involvement | 1.84 (1.03-3.29) | 0.041a | 0.86 (0.41-1.81) | 0. 689 |

| Pancreatic portal hypertension | 2.80 (1.27-6.16) | 0.010a | 2.81 (1.06-7.45) | 0.038a |

| Pancreatic duct dilation | 0.75 (0.42-1.34) | 0.329 | ||

| Preoperative EUS-FNA | 2.81 (1.16-6.81) | 0.022a | 2.66 (1.05-6.73) | 0.038a |

| Pancreatic texture | ||||

| Hard | Ref. | |||

| Soft | 1.11 (0.60-2.06) | 0.746 | ||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 1.47 (0.52-4.13) | 0.469 | ||

| Local invasion | 3.19 (1.23-8.29) | 0.017a | 1.97 (0.70-5.55) | 0.200 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2.33 (1.00-5.43) | 0.051 | ||

| Spleen preservation | 0.54 (0.34-0.84) | 0.006a | 0.83 (0.50-1.36) | 0.455 |

| Additional organ resection | 2.43 (0.34-17.44) | 0.378 | ||

| Lymph node dissection | 1.43 (0.93-2.20) | 0.100 | ||

| Malignancy | 1.58 (0.96-2.61) | 0.074 |

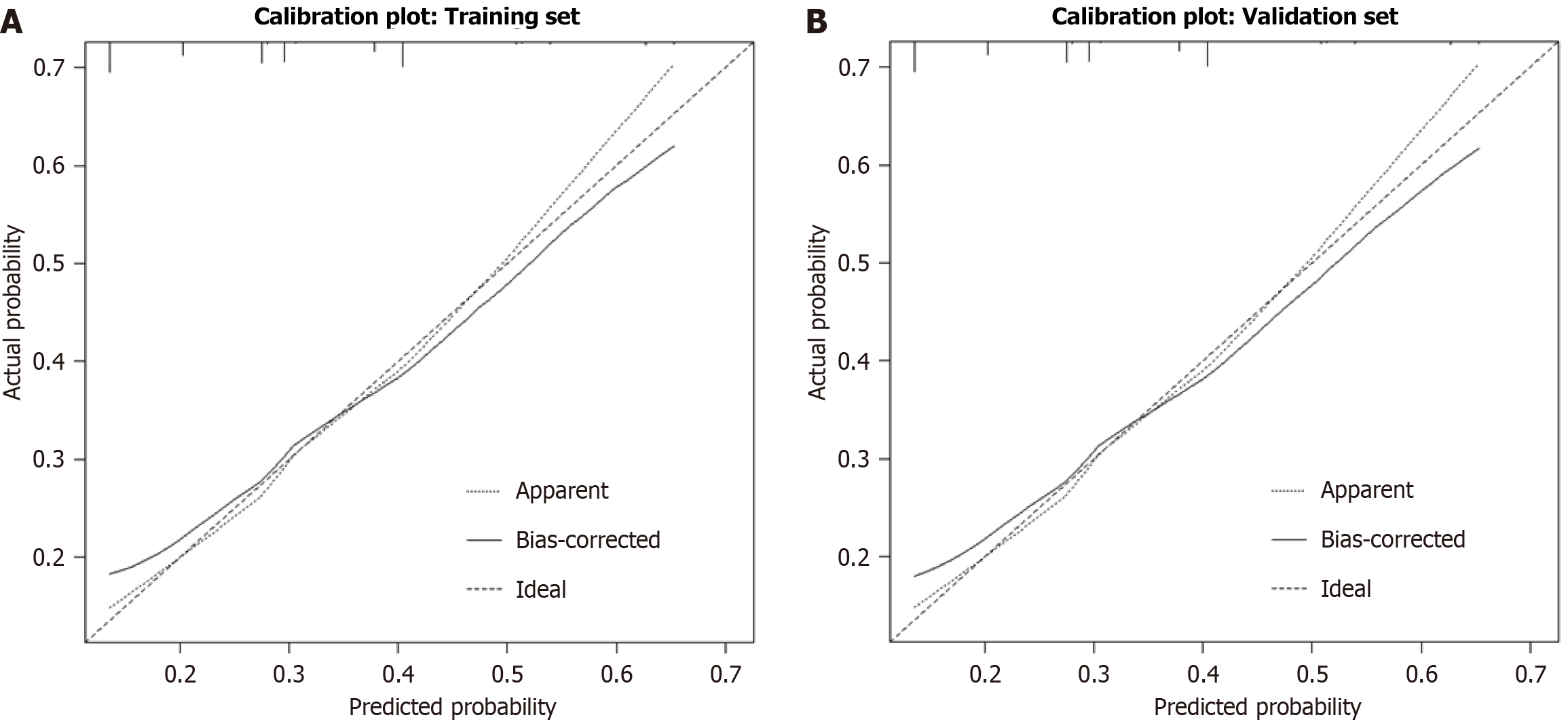

Utilizing the training cohort (n = 283), a risk-prediction model for TO failure was developed incorporating the four multivariate predictors sex, lesion consistency, pancreatic portal hypertension, and preoperative EUS-FNA and visualized as a nomogram (Figure 2). The C-indices were 0.661 (95%CI: 0.58-0.74) and 0.619 (95%CI: 0.53-0.71), respectively, indicating modest discrimination that marginally meets clinical acceptability. Calibration curves demonstrated close alignment between predicted and observed probabilities in both cohorts, with mean absolute errors of 0.020 and 0.022, respectively (Figure 3).

LDP has established itself as the standard treatment modality for lesions affecting the pancreatic body and tail in high-volume medical centers. Despite this, the absence of a robust tool for comparing perioperative quality among institutions remains a notable gap in the field. A pressing need exists for a metric that enables the benchmarking of LDP quality across institutions. Since 2013, the composite measure termed “TO” has gained prominence in gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, and pancreatic surgery as a comprehensive tool for assessing perioperative performance and guiding quality-improvement initiatives[15-18,22]. In pancreatic surgery specifically, TO has emerged as a critical instrument for addressing the limitations of single-indicator assessments. Nevertheless, current studies on TO display significant heterogeneity and imbalance.

The 2020 DPCG nationwide study was the first to introduce a TO specific to pancreatic surgery, requiring the absence of clinically significant POPF, bile leak, PPH (all grade B/C), severe complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III), 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality[18]. This TO definition, validated in over 3000 open and laparoscopic PD and DP cases, includes a criterion (bile leak) relevant only to procedures involving biliary reconstruction, rendering it inapplicable to DP. In 2021, a United States multicenter study proposed a “best pancreatic surgery” framework similar to TO but excluded PPH, compromising its completeness[26]. More recently, a 2024 Spanish six-center study developed a DP-specific TO that excluded prolonged LOS, Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III complications, in-hospital mortality, 90-day readmission, and POPF (grade B/C)[22]. However, this study combined open and laparoscopic cases and likewise ignored hemorrhage, limiting its ability to accurately depict the quality profile of LDP. Consequently, the existing body of evidence on TO predominantly concentrates on PD, with limited and inconsistent studies on DP. A dedicated TO investigation specifically focusing on a pure LDP cohort is currently lacking.

Building on the 2020 DPCG nationwide study and recognizing the absence of biliary anastomosis in LDP, we have refined the LDP-specific TO criteria to encompass the absence of POPF (grade B/C), PPH (grade B/C), severe morbidity (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III), 30-day readmission, and in-hospital or 30-day mortality[18]. Prolonged LOS was intentionally omitted due to its susceptibility to non-medical influences such as patient preference, bed availability, or insurance policies. By explicitly incorporating PPH, our definition addresses the predominant hemorrhagic complication specific to LDP, filling a crucial assessment gap and ensuring that TO accurately reflects operative technical quality and perioperative care effectiveness.

Among the 405 patients who underwent LDP in our study, 286 individuals (70.6%) achieved TO, surpassing the 67.4% reported for the LDP subgroup in the 2020 DPCG nationwide study[18] and the 58.2% recorded in a recent Spanish DP cohort[22]. This superior performance likely reflects both institutional volume and metric selection: Our institution performs over 80 LDP procedures annually, and the accrued expertise has been demonstrated to lower rates of intraoperative bleeding, POPF, and PPH. Moreover, by excluding prolonged LOS a variable influenced by external factors such as insurance policies and bed availability we circumvented the potential distortion of TO outcomes observed when LOS is included (the DPCG DP rate dropped from 67.4% to 63.3% after adding LOS), thereby providing a more accurate measure of surgical quality.

Univariate and multivariate analyses concordantly identified female sex, pre-operative EUS-FNA, pancreatic portal hypertension, and lesion consistency as independent predictors of TO failure following LDP.

Female sex emerged as a protective factor against TO failure in our cohort (OR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.39-0.99, P = 0.046), consistent with the DPCG finding that female sex was a positive predictor of TO achievement (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.01-1.90, P = 0.05)[18]. This protective association has been corroborated by larger datasets: A 2022 United States nationwide analysis of 1950 pancreatectomies showed that women more frequently attained an “ideal outcome” and outperformed men in all TO component (severe complications, 30-day mortality, re-operation, readmission)[27]. Similarly, the 2022 German pancreas registry (n = 10224) reported lower overall morbidity (57.3% vs 60.1%, P = 0.005), mortality (3.4% vs 4.9%, P < 0.001) and clinically relevant POPF after DP (22.5% vs 27.3%, P = 0.012) in females[28]. In our study, POPF rates were nearly halved in women (15.1% vs 25.6%, P = 0.009), while other major complications and 30-day mortality rates were comparable between genders. Given that POPF represents the primary barrier to TO after LDP, the favorable outcomes observed in females likely stem from an inherently lower risk of fistula formation. However, prospective multicenter investigations are warranted to establish causality.

At high-volume centers, EUS-FNA serves as an important preoperative diagnostic modality for both cystic and solid pancreatic lesions[29,30]. While EUS-FNA enhances diagnostic accuracy for pancreatic neoplasms with a low overall complication rate (3.4%)[30], it is an invasive maneuver that may induce local pancreatic inflammation or minor ductal injury, potentially increasing the risk of postoperative fistula formation. Additionally, complications such as hemorrhage, perforation, infection, and needle-tract seeding have been reported in specific cases[31,32]. In our series, patients sub

Patients with concurrent pancreatic portal hypertension had a significantly higher risk of TO failure (OR = 2.94, 95%CI: 1.11-7.76, P = 0.030). Pancreatic portal hypertension commonly results from recurrent episodes of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis or direct tumor invasion of the splenic vein[33]. Chronic inflammation damages the endothelium of the splenic vein, leading to thrombosis and thickening of the vessel wall, while causing diffuse fibrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma with areas of edema or pseudocysts, significantly increasing tissue vulnerability[34]. This process also results in collateral dilation of the short gastric and left gastroepiploic veins, forming a delicate vascular network that is prone to bleeding during surgical dissection. Consequently, during LDP, the glandular transection plane becomes uneven and fragile, complicating secure closure with staples or sutures and heightening the risk of POPF; dilated collateral ves

Patients with mixed cystic-solid (OR = 2.60, 95%CI: 1.40-4.82, P = 0.002) and solid lesions (OR = 1.99, 95%CI: 1.11-3.55, P = 0.020) were associated with markedly lower TO rates compared to those with purely cystic lesions. This disparity is likely attributable to the benign nature of cystic lesions (e.g., serous cystadenoma), which can often be excised with simple resection without lymph-node dissection, resulting in minimal surgical trauma and low complication rates[30]. In contrast, cystic-solid or solid lesions, such as solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, or neuroendocrine tumors, often necessitate extensive resection and lymph node clearance, leading to larger surgical fields and prolonged operative durations. Furthermore, the higher micro-vessel density in solid lesions heightens the risk of intraoperative bleeding, increasing the likelihood of POPF and intra-abdominal infections[35,36]. Therefore, tailored ma

Additionally, utilizing the independent predictors of TO failure identified through multivariable analysis sex, preo

Importantly, it should be acknowledged that TO was conceived as a surrogate indicator for perioperative technical quality rather than a reflection of patient-centered endpoints such as quality of life, pain, fatigue, or time to functional recovery. Surgeons traditionally track mortality and morbidity, whereas administrators emphasize cost and LOS; patients, however, prioritize symptom relief, return to normal activities, and long-term well-being. Consequently, over-interpreting TO as a comprehensive measure of “surgical success” risks creating an illusion of excellence while neglecting outcomes that matters most to patients. Future prospective studies should integrate patient-reported outcome measures and functional recovery scores to better align quality assessment with patient priorities and to clarify whether achieving TO truly translates into improved quality of life after LDP.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, being a single-center retrospective cohort, it is susceptible to selection bias, necessitating caution when generalizing the findings to community or low-volume centers. Subsequent research should encompass external cohorts from diverse regions and institutions with varying case volumes to validate the applicability of our TO criteria and risk factors. Secondly, the model development and validation were performed within the same institution, lacking a fully independent external dataset and potentially overestimating predictive performance. Pro

In this single-institution cohort of 405 patients, we established a tailored TO for LDP, defined as the absence of grade B/C POPF, grade B/C PPH, Clavien-Dindo ≥ III morbidity, 30-day readmission, in-hospital, and 30-day mortality. TO was achieved in 70.6% of cases, serving as a robust standard for perioperative quality assessment. Our analysis identified female sex as a protective factor, while preoperative EUS-FNA, pancreatic portal hypertension, and cystic-solid or solid lesion consistency independently predicted TO failure. Leveraging these insights, we developed and internally validated a nomogram that translates these factors into individualized risk estimations, providing a practical and standardized tool for preoperative risk assessment and ongoing quality enhancement in LDP.

We acknowledge all patients who contributed to this study.

| 1. | Lof S, Claassen L, Hannink G, Al-Sarireh B, Björnsson B, Boggi U, Burdio F, Butturini G, Capretti G, Casadei R, Dokmak S, Edwin B, Esposito A, Fabre JM, Ferrari G, Fretland AA, Ftériche FS, Fusai GK, Giardino A, Groot Koerkamp B, D'Hondt M, Jah A, Kamarajah SK, Kauffmann EF, Keck T, van Laarhoven S, Manzoni A, Marino MV, Marudanayagam R, Molenaar IQ, Pessaux P, Rosso E, Salvia R, Soonawalla Z, Souche R, White S, van Workum F, Zerbi A, Rosman C, Stommel MWJ, Abu Hilal M, Besselink MG; European Consortium on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (E-MIPS). Learning Curves of Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy in Experienced Pancreatic Centers. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:927-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cucchetti A, Bocchino A, Crippa S, Solaini L, Partelli S, Falconi M, Ercolani G. Advantages of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and matched studies. Surgery. 2023;173:1023-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Konishi T, Takamoto T, Fujiogi M, Hashimoto Y, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Tanabe M, Seto Y, Yasunaga H. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy: A propensity score analysis in Japan. Int J Surg. 2022;104:106765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Riviere D, Gurusamy KS, Kooby DA, Vollmer CM, Besselink MG, Davidson BR, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Pastena M, van Bodegraven EA, Mungroop TH, Vissers FL, Jones LR, Marchegiani G, Balduzzi A, Klompmaker S, Paiella S, Tavakoli Rad S, Groot Koerkamp B, van Eijck C, Busch OR, de Hingh I, Luyer M, Barnhill C, Seykora T, Maxwell T T, de Rooij T, Tuveri M, Malleo G, Esposito A, Landoni L, Casetti L, Alseidi A, Salvia R, Steyerberg EW, Abu Hilal M, Vollmer CM, Besselink MG, Bassi C. Distal Pancreatectomy Fistula Risk Score (D-FRS): Development and International Validation. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e1099-e1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Coco D, Leanza S, Schillaci R, Reina GA. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for benign and malignant disease: a review of techniques and results. Prz Gastroenterol. 2022;17:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ban D, Nishino H, Ohtsuka T, Nagakawa Y, Abu Hilal M, Asbun HJ, Boggi U, Goh BKP, He J, Honda G, Jang JY, Kang CM, Kendrick ML, Kooby DA, Liu R, Nakamura Y, Nakata K, Palanivelu C, Shrikhande SV, Takaori K, Tang CN, Wang SE, Wolfgang CL, Yiengpruksawan A, Yoon YS, Ciria R, Berardi G, Garbarino GM, Higuchi R, Ikenaga N, Ishikawa Y, Kozono S, Maekawa A, Murase Y, Watanabe Y, Zimmitti G, Kunzler F, Wang ZZ, Sakuma L, Osakabe H, Takishita C, Endo I, Tanaka M, Yamaue H, Tanabe M, Wakabayashi G, Tsuchida A, Nakamura M. International Expert Consensus on Precision Anatomy for minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy: PAM-HBP Surgery Project. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29:161-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Bodegraven EA, Francken MFG, Verkoulen KCHA, Abu Hilal M, Dijkgraaf MGW, Besselink MG. Costs of complications following distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2023;25:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Song KB, Hong S, Kim HJ, Park Y, Kwon J, Lee W, Jun E, Lee JH, Hwang DW, Kim SC. Predictive Factors Associated with Complications after Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smits FJ, Verweij ME, Daamen LA, van Werkhoven CH, Goense L, Besselink MG, Bonsing BA, Busch OR, van Dam RM, van Eijck CHJ, Festen S, Koerkamp BG, van der Harst E, de Hingh IH, Kazemier G, Klaase JM, van der Kolk M, Liem M, Luyer MDP, Meerdink M, Mieog JSD, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Roos D, Schreinemakers JM, Stommel MW, Wit F, Zonderhuis BM, de Meijer VE, van Santvoort HC, Molenaar IQ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Impact of Complications After Pancreatoduodenectomy on Mortality, Organ Failure, Hospital Stay, and Readmission: Analysis of a Nationwide Audit. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e222-e228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nimptsch U, Krautz C, Weber GF, Mansky T, Grützmann R. Nationwide In-hospital Mortality Following Pancreatic Surgery in Germany is Higher than Anticipated. Ann Surg. 2016;264:1082-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kolfschoten NE, Kievit J, Gooiker GA, van Leersum NJ, Snijders HS, Eddes EH, Tollenaar RA, Wouters MW, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. Focusing on desired outcomes of care after colon cancer resections; hospital variations in 'textbook outcome'. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Nolan T, Berwick DM. All-or-none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA. 2006;295:1168-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu Y, Wujimaimaiti N, Yuan J, Li S, Zhang H, Wang M, Qin R. Risk factors for achieving textbook outcome after laparoscopic duodenum-preserving total pancreatic head resection: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2023;109:698-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lucocq J, Scollay J, Patil P. Evaluation of Textbook Outcome as a Composite Quality Measure of Elective Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2232171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Levy J, Gupta V, Amirazodi E, Allen-Ayodabo C, Jivraj N, Jeong Y, Davis LE, Mahar AL, De Mestral C, Saarela O, Coburn NG; PRESTO Group. Textbook Outcome and Survival in Patients With Gastric Cancer: An Analysis of the Population Registry of Esophageal and Stomach Tumours in Ontario (PRESTO). Ann Surg. 2022;275:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Görgec B, Benedetti Cacciaguerra A, Lanari J, Russolillo N, Cipriani F, Aghayan D, Zimmitti G, Efanov M, Alseidi A, Mocchegiani F, Giuliante F, Ruzzenente A, Rotellar F, Fuks D, D'Hondt M, Vivarelli M, Edwin B, Aldrighetti LA, Ferrero A, Cillo U, Besselink MG, Abu Hilal M. Assessment of Textbook Outcome in Laparoscopic and Open Liver Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:e212064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Roessel S, Mackay TM, van Dieren S, van der Schelling GP, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Bosscha K, van der Harst E, van Dam RM, Liem MSL, Festen S, Stommel MWJ, Roos D, Wit F, Molenaar IQ, de Meijer VE, Kazemier G, de Hingh IHJT, van Santvoort HC, Bonsing BA, Busch OR, Groot Koerkamp B, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Textbook Outcome: Nationwide Analysis of a Novel Quality Measure in Pancreatic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;271:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mohamed A, Nicolais L, Fitzgerald TL. Textbook outcome as a composite measure of quality in hepaticopancreatic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:1172-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsilimigras DI, Pawlik TM, Moris D. Textbook outcomes in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:1524-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yuan J, Du C, Wu H, Zhong T, Zhai Q, Peng J, Liu N, Li J. Risk factors of failure to achieve textbook outcome in patients after pancreatoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:3093-3106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Villodre C, Del Río-Martín J, Blanco-Fernández G, Cantalejo-Díaz M, Pardo F, Carbonell S, Muñoz-Forner E, Carabias A, Manuel-Vazquez A, Hernández-Rivera PJ, Jaén-Torrejimeno I, Kälviäinen-Mejia HK, Rotellar F, Garcés-Albir M, Latorre R, Longoria-Dubocq T, De Armas-Conde N, Serrablo A, Esteban Gordillo S, Sabater L, Serradilla-Martín M, Ramia JM. Textbook outcome in distal pancreatectomy: A multicenter study. Surgery. 2024;175:1134-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CM, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3041] [Cited by in RCA: 3215] [Article Influence: 357.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 24. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 2067] [Article Influence: 108.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9215] [Article Influence: 542.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Beane JD, Borrebach JD, Zureikat AH, Kilbane EM, Thompson VM, Pitt HA. Optimal Pancreatic Surgery: Are We Making Progress in North America? Ann Surg. 2021;274:e355-e363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Roalsø MT, Nymo LS, Kleive D, Waardal K, Dille-Amdam R, Søreide K. Sex Disparity and Procedure-Related Differences in Achieving an Ideal Outcome after Pancreatic Surgery: A National Observational Cohort Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2025;241:669-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Damanakis AI, Toader J, Wahler I, Plum P, Quaas A, Ernst A, Popp F, Gebauer F, Bruns C. Influence of patient sex on outcomes after pancreatic surgery: multicentre study. Br J Surg. 2022;109:746-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Machicado JD, Sheth SG, Chalhoub JM, Forbes N, Desai M, Ngamruengphong S, Papachristou GI, Sahai V, Nassour I, Abidi W, Alipour O, Amateau SK, Coelho-Prabhu N, Cosgrove N, Elhanafi SE, Fujii-Lau LL, Kohli DR, Marya NB, Pawa S, Ruan W, Thiruvengadam NR, Thosani NC, Qumseya BJ; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of solid pancreatic masses: summary and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;100:786-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1144] [Cited by in RCA: 976] [Article Influence: 122.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Terasawa H, Matsumoto K, Tanaka T, Tomoda T, Ogawa T, Ishihara Y, Kikuchi T, Obata T, Oda T, Matsumi A, Miyamoto K, Morimoto K, Fujii Y, Yamazaki T, Uchida D, Horiguchi S, Tsutsumi K, Kato H, Otsuka M. Cysts or necrotic components in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is associated with the risk of EUS-FNA/B complications including needle tract seeding. Pancreatology. 2023;23:988-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kitano M, Yoshida T, Itonaga M, Tamura T, Hatamaru K, Yamashita Y. Impact of endoscopic ultrasonography on diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:19-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Zhang Y, Su Q, Li Y, Zhan X, Wang X, Zhang L, Luo H, Kang X, Lv Y, Liang S, Ren G, Pan Y. Development of a nomogram for predicting pancreatic portal hypertension in patients with acute pancreatitis: a retrospective study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2024;11:e001539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tidwell J, Thakkar B, Wu GY. Etiologies of Splenic Venous Hypertension: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2024;12:594-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lennon AM, Vege SS. Pancreatic Cyst Surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1663-1667.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Younan G. Pancreas Solid Tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:565-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/