Published online Nov 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i42.112577

Revised: September 4, 2025

Accepted: October 13, 2025

Published online: November 14, 2025

Processing time: 105 Days and 17.6 Hours

Bismuth quadruple therapy (BQT) induces troublesome gastrointestinal side effects that reduce adherence and efficacy.

To evaluate multistrain probiotics efficacy for alleviating gastrointestinal sym

One hundred seventy-four adults (18-60 years) with confirmed H. pylori infections between July 2022 and December 2023 were randomised to receive BQT plus a multispecies probiotic (n = 89) or a maltodextrin placebo (n = 85) for 4 weeks. Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Bristol Stool Classification Scale scores were collected at baseline, 2, 4 and 8 weeks; eradication was assessed 8 weeks post-treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis used multiple imputation and SPSS 26.0.

After 8 weeks, GSRS scores (all dimensions and total) decreased significantly compared with those at baseline. ITT analysis showed significantly greater reductions for the intervention vs the placebo in reflux by week 2, total/diarrhea scores by week 4, and total/dyspepsia scores by week 8. Probiotics provided no protective effect against gastrointestinal symptoms at week 2 but showed significant protection at weeks 4 and 8. Both groups reported decreased diarrhea/constipation-type stools and increased normal-type stools post-intervention. H. pylori eradication rates were slightly higher for the intervention group (88.8%) than for the placebo group (84.7%), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.430).

Multistrain probiotics significantly relieved BQT-associated gastrointestinal symptoms without affecting era

Core Tip: In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 174 adults, a 4-week multistrain probiotics formula mainly containing five Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species added to bismuth quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection significantly reduced reflux, dyspepsia and diarrhea scores at weeks 4-8 without affecting eradication rates. Probiotics are a safe adjunct to ease antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Citation: Liu WJ, Zhao YM, Xie QQ, Wu MC, Pan YF, Yan HK, Shan XX, Xu WT, Liu YL, Peng CX, Zhang XM, Lin Q. Multistrain probiotics alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms during bismuth quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(42): 112577

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i42/112577.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i42.112577

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative bacterium that was first isolated and cultured by Marshall and Warren in 1983 from the gastric mucosa of patients diagnosed with gastritis and peptic ulcers[1]. A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis published in the journal Gastroenterology in January 2024 reported a global adult H. pylori infection rate of 43.9%, with a rate of 42.3% among adults in China[2]. In China, H. pylori infection is characterized by a high prevalence, substantial disease burden, and significant levels of drug resistance. Humans are universally susceptible to H. pylori and represent its only natural host. All naturally occurring strains of H. pylori are pathogenic, and all infected individuals exhibit pathologically active gastritis. Over 90% of duodenal ulcers and 70% to 80% of gastric ulcers are attributable to H. pylori infection, with 1% to 2% of infected individuals developing gastric cancer[3-5]. Moreover, H. pylori infection is strongly associated with a range of extragastrointestinal diseases, including iron deficiency anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases. H. pylori is widely disseminated and potentially harmful, making it a major public health concern[6]. Therefore, eradicating H. pylori is urgently important to prevent and mitigate the occurrence of associated diseases.

Antibiotic therapy is currently considered the primary method for H. pylori eradication. Bismuth is considered safe, effective, and inexpensive; the bismuth quadruple regimen is recommended as the first-line treatment for H. pylori eradication in China. Compared with the triple regimen, the bismuth quadruple regimen has a greater eradication rate for H. pylori infection, a benefit that remains consistent across subgroup analyses of various antimicrobial combinations. However, this regimen is associated with certain drawbacks, including an increased incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abnormal bowel movements during treatment. These adverse effects may impact patient compliance, which, in turn, affects the success of eradication therapy. Therefore, further research is urgently needed to explore novel treatment options or adjunctive therapies.

Probiotic agents, as emerging adjunctive therapies, have demonstrated potential advantages in H. pylori eradication in recent years. A meta-analysis demonstrated that probiotic supplementation in a quadruple regimen can improve the H. pylori eradication rate[7], potentially through the ability of probiotics to combat H. pylori through competitive in

The current research on the role of probiotics in H. pylori eradication treatment is limited and inconclusive, and there is a lack of standardization regarding the types, number, and duration of probiotic strains, which warrants further investigation. Consequently, a more in-depth and comprehensive study is needed to build on existing data and thoroughly evaluate the effects of probiotics on H. pylori eradication and their underlying mechanisms of action.

Accordingly, the present study was designed as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving adults with a primary diagnosis of H. pylori infection, aimed at evaluating the efficacy of a multifactorial probiotic preparation (primarily consisting of five Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species) in alleviating gastrointestinal symptoms associated with H. pylori infection and providing a scientific foundation for anti-H. pylori treatment.

This study was conducted from July 2022 to December 2023 at Xiangya Hospital of Central South University in Changsha, Hunan Province. The study participants were aged between 18 years and 60 years and had been diagnosed as H. pylori-positive by a urea breath test within the past month and had not received any treatment. After initial screening, pa

Inclusion criteria: (1) Aged 18 to 60 years; (2) Positive result on the 13C urea breath test (13C-UBT) or 14C urea breath test

Exclusion criteria: (1) Had not resided locally for at least 6 months in the past year; (2) Had severe cardiovascular, gastrointestinal (e.g., colon cancer, severe enteritis, or intestinal obstruction), hepatic, renal, endocrine, or psychiatric disorders; (3) Had undergone surgical procedures in the past 6 months; (4) Had used probiotics, antibiotics, bismuth, or laxatives in the past month; (5) Were pregnant or lactating; and (6) Were allergic to lactose or fructose or had been diagnosed with lactose malabsorption.

Bismuth quadruple therapy program: The study participants received 2 weeks of BQT according to the following dosing regimen: Amoxicillin capsules (Qionggong Sanyang, 0.25 g × 50), 1 g; doxycycline capsules (Sukunshan Yongxin, 0.1 g × 10), 0.1 g; rabeprazole enteric-coated tablets (Eisai China Pharmaceutical, 10 mg × 7), 10 mg twice daily; and colloidal bismuth tartrate capsules (Jinxin Baoyuan System, 55 mg × 36), 220 mg three times daily.

Specific characteristics of the multistrain probiotics preparation and placebo preparation: The probiotic preparation used in this study was an active lactobacilli compound powder (3 g per strip) containing live bacteria at ≥ 2.0 × 1010 CFU per strip (at the time of shipment). The main ingredients included Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum. This formulation has been clinically validated in both animal and human studies, including trials on postoperative intestinal function and the eradication of H. pylori, and has been available since 2019. The placebo used in this study was maltodextrin, which has identical packaging and specifications as the probiotic preparation. Maltodextrin is characterized by low sweetness, low caloric content, low osmolality, and ease of absorption. Maltodextrin has been demonstrated to be safe and nonharmful to humans and is commonly used as a placebo in probiotic intervention trials.

The participants in the intervention group received 4 weeks of probiotic supplementation in addition to 2 weeks of BQT, whereas those in the placebo-controlled group received 4 weeks of maltodextrin supplementation along with 2 weeks of BQT. The probiotic preparation or maltodextrin was administered as follows: 1 strip was taken 2 hours after antibiotic administration with warm water, twice daily.

Questionnaire survey: The general demographic data of the study participants were collected at baseline with an electronic questionnaire, and gastrointestinal symptoms and stool types were assessed at baseline and after 2, 4, and 8 weeks of the intervention. The questionnaire included the following details: (1) Basic information: Age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education level, occupation, income, smoking history, and drinking history; (2) Gastrointestinal symptoms gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed by the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), which consists of 15 items (including abdominal pain, heartburn, acid reflux, nausea/vomiting, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, urgency to defecate, and incomplete defecation). The GSRS is organized into five dimensions: Reflux syndrome, abdominal pain syndrome, dyspepsia, diarrhea syndrome, and constipation syndrome. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale for symptom severity, ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (severe symptoms). Each dimension includes 2 to 4 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 24. The total GSRS score is the sum of the scores for all dimensions, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The GSRS has been translated into several languages and has good internal consistency and reliability; (3) Stool type: Stool type was assessed by the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS), a widely used tool for evaluating bowel motility, which categorizes stool types from hard to watery on a 7-point scale. The scale classifies stool types from type I (hard) to type VII (watery), with visual depictions for each type; and (4) Adherence: Adherence was assessed at 2 and 4 weeks of intervention through questionnaires, which asked whether participants took the prescribed medication and probiotic preparation (or placebo) as directed in terms of timing and dosage. In this study, good adherence was defined as taking ≥ 80% of the prescribed medication and probiotics (for ≥ 11 days) as directed during the first 2 weeks and ≥ 80% adherence (for ≥ 22 days) during the 4-week intervention. This level of adherence was considered indicative of successful trial completion.

Follow-up: A case report book was provided to all participants, who were instructed to document the weekly administration of medication and either the probiotic or placebo preparation, as well as any gastrointestinal symptoms or bowel movements during the intervention period. Follow-up visits were conducted after 2, 4, and 8 weeks via telephone or WeChat, during which participants completed questionnaires to assess adherence to the intervention protocol.

Occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms: The total score of the GSRS and the scores of its five dimensions—reflux syndrome, abdominal pain syndrome, dyspepsia, diarrhea syndrome, and constipation syndrome—were assessed in both groups before and after the intervention. Additionally, changes in the total GSRS score and scores for each dimension were evaluated at baseline and after 2, 4, and 8 weeks of intervention.

Incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms: Incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms = number of participants with gastrointestinal symptoms/total number of participants × 100%.

Relative risk reduction: Relative risk reduction = (|incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the placebo - controlled group - incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the intervention group|)/(incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the placebo - controlled group) × 100%.

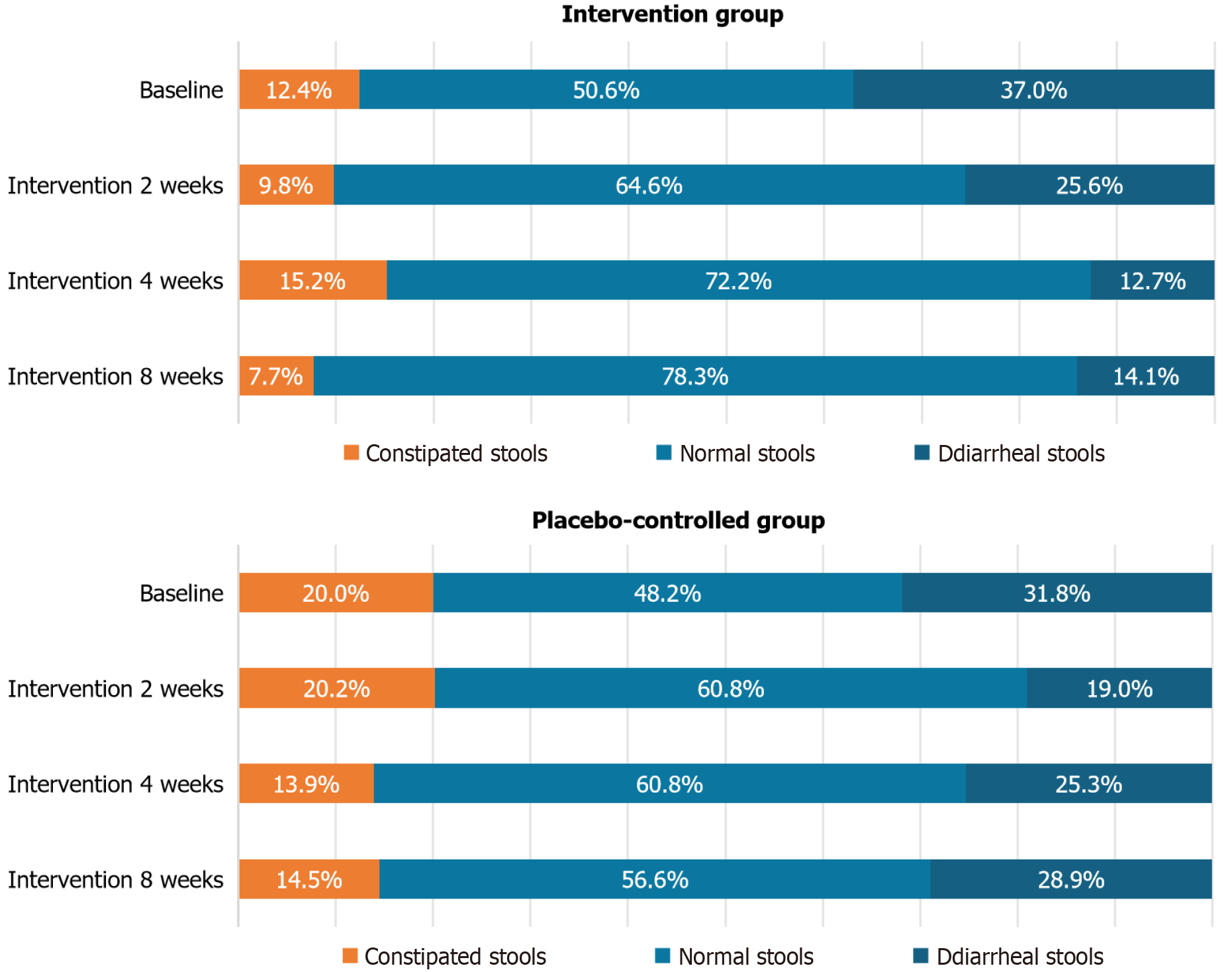

BSFS: In this study, stool types were classified according to the BSFS as follows - types I and II were categorized as constipated stools; types III and IV were categorized as normal stools; and types V, VI, and VII were categorized as diarrheal stools. The incidence of both diarrhea and constipation was assessed after 2, 4, and 8 weeks of intervention.

Eradication rate: Eradication rate (ER) of H. pylori in the study population, evaluated 8 weeks after baseline (i.e., 4 weeks following the completion of eradication treatment): ER = review of H. pylori negative individuals/total number of participants × 100%.

On the basis of a review of the literature, it was assumed that 16% of participants in the intervention group and 36% in the placebo-controlled group would exhibit diarrhea symptoms (as determined by the BSFS) after four weeks of intervention. With a type I error rate of 0.05 and a power of 80%, the required sample size was estimated to be 72 participants per group. To account for a 20% dropout rate, a total of 87 participants were needed from each group, resulting in a total of 174 participants for the study. The sample size was calculated with PASS 15.0 software as follows:

In this study, fixed-block randomization (fixed block size = 30) was implemented with the R software (version 3.6.3) random package. Participants were randomly assigned to the multistrain probiotics group or the placebo group, at a 1:1 ratio. A table containing 30 random numbers was generated every two months for a total of six times. Each set of 30 numbers was sequentially matched to the corresponding random numbers, sorted in ascending order. The first 15 numbers were assigned to the intervention group, and the last 15 numbers were assigned to the placebo-controlled group. The corresponding probiotic or placebo products were then placed into labeled bags on the basis of these assignments.

To conceal the randomization process, the envelope method was used. The researcher responsible for generating the randomization sequence placed the grouping information (including the number, random digit, serial number, and group) along with the randomized table into opaque kraft paper envelopes. These envelopes were stored by the project leader and were only unsealed at the end of the study by the project team mentor, the randomization sequence generator, and the project leader. The recruiter, who was not involved in the randomization process, was solely responsible for distributing the products to the study participants according to the enrollment order.

This study used a double-blind design, in which both the investigators (including clinicians) and the participants were unaware of group assignments. Both the probiotic and placebo preparations were packaged identically and had the same physical characteristics to maintain blinding throughout the study.

SPSS version 26.0 was used for data cleaning, organization, and statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (i.e., de

Full data analysis set (ITT analysis): The full data analysis set included all study participants who were randomized and assigned a random number, referred to as the ITT population. This dataset analyzed the outcomes for all participants, including those who were lost to follow-up, by multiple imputation techniques.

Protocol-compliant data analysis set (PP analysis): Prior to the start of the study, the researcher conducted a test of the questionnaire, which took 8-10 minutes to complete. The PP analysis set excluded participants with poor medication adherence, dropouts, or incomplete questionnaire data, including those who took less than 6 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

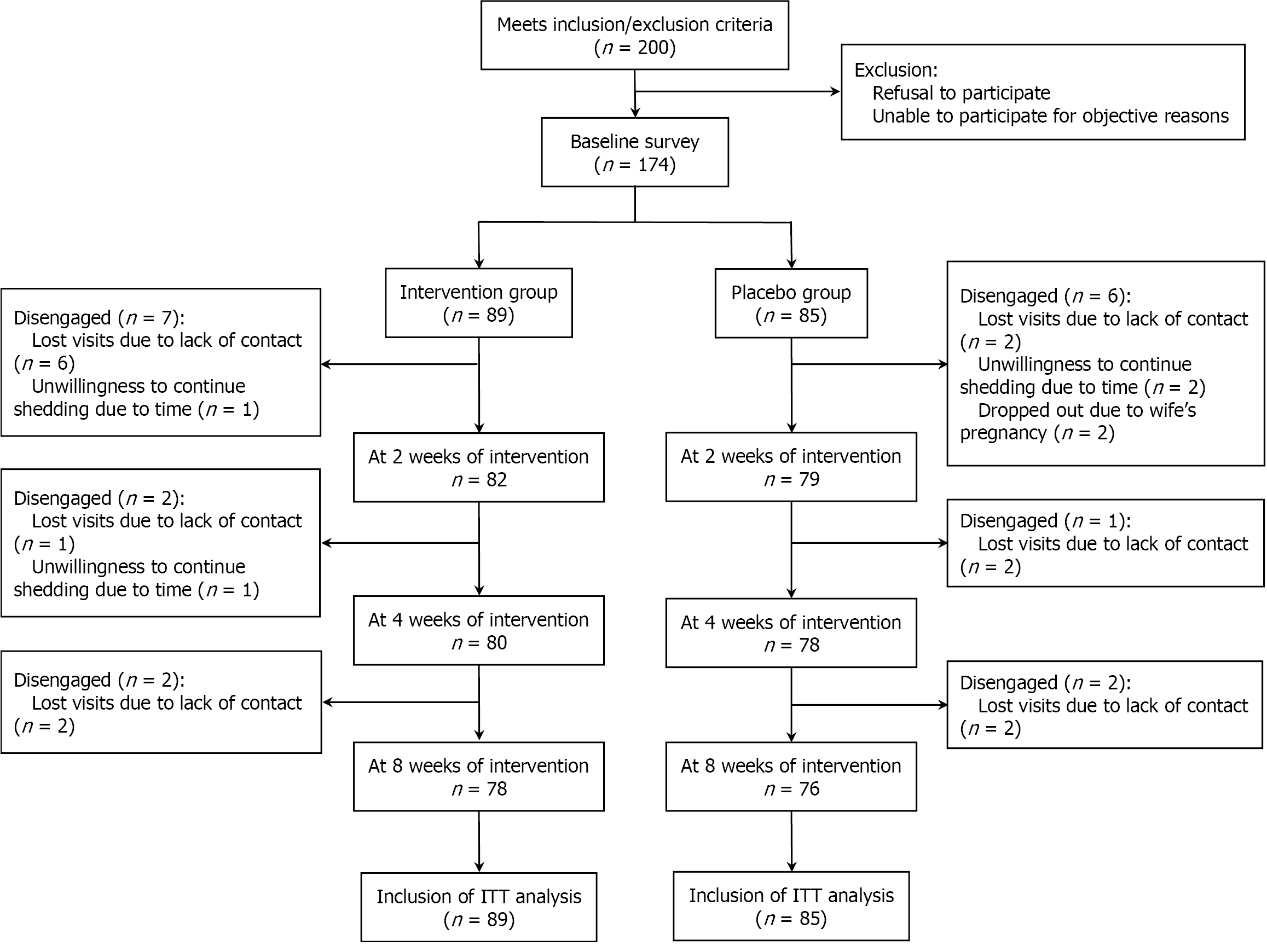

This study was conducted between July 2022 and December 2023. A total of 174 participants were enrolled at baseline, with 154 completing the 8-week intervention, resulting in a dropout rate of 11.5% (20/174). Among the 89 participants in the intervention group, 11 were lost to follow-up by 8 weeks (9 due to lack of contact and 2 who chose to discontinue for personal reasons), whereas 85 participants were enrolled in the placebo-controlled group, with 9 dropping out by the end of the study (5 due to lack of contact, 2 who discontinued for personal reasons, and 2 who withdrew because of a family-related pregnancy). The flow of study participants is illustrated in Figure 1.

A total of 174 individuals with H. pylori infection were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of all participants. No significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to sex, age, body mass index, ethnicity, household attributes, marital status, education, occupation, per capita monthly income, smoking, alcohol consumption, reason for medical consultation, or 13C/14C breath test scores (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Total population (n = 174) | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | χ²/t | P value |

| Sex | 2.271 | 0.132 | |||

| Male | 63 (36.2) | 37 (41.6) | 26 (30.6) | ||

| Female | 111 (63.8) | 52 (58.4) | 59 (69.4) | ||

| Age, years | 2.987 | 0.394 | |||

| ≤ 29 | 49 (28.2) | 26 (29.2) | 23 (27.1) | ||

| 30-39 | 59 (33.9) | 25 (28.1) | 34 (40.0) | ||

| 40-49 | 35 (20.1) | 20 (22.5) | 15 (17.6) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 31 (17.8) | 18 (20.2) | 13 (15.3) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.081 | 0.960 | |||

| < 18.5 | 12 (6.9) | 6 (6.7) | 6 (7.1) | ||

| 18.5-23.9 | 107 (61.5) | 54 (60.7) | 53 (62.4) | ||

| ≥ 24.0 | 55 (31.6) | 29 (32.6) | 26 (30.6) | ||

| Ethnic group | 0.528 | 0.468 | |||

| Han | 164 (94.3) | 85 (95.5) | 79 (92.9) | ||

| Other | 10 (5.7) | 4 (4.5) | 6 (7.1) | ||

| Household characteristics | 0.169 | 0.681 | |||

| Urban | 101 (58.0) | 53 (59.6) | 48 (56.5) | ||

| Rural | 73 (42.0) | 36 (40.4) | 37 (43.5) | ||

| Marital status | 1.316 | 0.518 | |||

| Unmarried | 45 (25.9) | 25 (28.1) | 20 (23.5) | ||

| Married | 118 (67.8) | 60 (67.4) | 58 (68.2) | ||

| Other | 11 (6.3) | 4 (4.5) | 7 (8.2) | ||

| Education | 0.109 | 0.991 | |||

| Junior high school and below | 21 (12.1) | 11 (12.4) | 10 (11.8) | ||

| High school | 26 (14.9) | 13 (14.6) | 13 (15.3) | ||

| College/vocational university | 28 (16.1) | 15 (16.9) | 13 (15.3) | ||

| Bachelor's degree and above | 99 (56.9) | 50 (56.1) | 49 (57.6) | ||

| Vocation | 0.708 | 0.702 | |||

| Working | 101 (58.0) | 50 (56.2) | 51 (60.0) | ||

| Unemployed/household | 25 (14.4) | 12 (13.5) | 13 (15.3) | ||

| Other | 48 (27.6) | 27 (30.3) | 21 (24.7) | ||

| Per capita monthly income (CNY) | 2.358 | 0.670 | |||

| < 4000 | 46 (26.4) | 23 (25.8) | 23 (27.1) | ||

| 4001-6000 | 33 (19.0) | 20 (22.5) | 13 (15.3) | ||

| 6001-8000 | 31 (17.8) | 17 (19.1) | 14 (16.5) | ||

| 8001-10000 | 19 (10.9) | 8 (9.0) | 11 (12.9) | ||

| > 10000 | 45 (25.9) | 21 (23.6) | 24 (28.2) | ||

| Smoking | 0.009 | 0.923 | |||

| Yes | 16 (9.2) | 8 (9.0) | 8 (9.4) | ||

| Drinking | 0.071 | 0.789 | |||

| Yes | 76 (43.7) | 38 (42.7) | 38 (44.7) | ||

| Reason for visit | 1.446 | 0.485 | |||

| Digestive discomfort | 109 (62.6) | 52 (58.4) | 57 (67.1) | ||

| Chronic gastritis | 52 (29.9) | 30 (33.7) | 22 (25.9) | ||

| Ulcers | 13 (7.5) | 7 (7.9) | 6 (7.0) | ||

| 13C/14C expiratory value | 22.23 ± 16.17 | 21.94 ± 15.48 | 23.80 ± 16.93 | 0.739 | 0.461 |

As shown in Table 2, prior to the intervention, the GSRS reflux syndrome score was significantly higher in the inter

| Variables | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | Z | P value |

| Baseline | ||||

| Reflux syndrome | 3.87 ± 2.13 | 3.09 ± 1.43 | -2.606 | 0.009b |

| Abdominal pain syndrome | 2.76 ± 2.91 | 2.44 ± 2.94 | -0.999 | 0.318 |

| Dyspepsia | 5.78 ± 4.61 | 4.79 ± 3.71 | -1.232 | 0.218 |

| Diarrhea | 3.76 ± 3.78 | 3.13 ± 3.02 | -0.876 | 0.381 |

| Constipation | 2.75 ± 3.50 | 2.56 ± 3.34 | -0.370 | 0.711 |

| GSRS total score | 18.67 ± 12.75 | 16.25 ± 10.43 | -1.094 | 0.274 |

| After 4 weeks of intervention | ||||

| Reflux syndrome | 0.55 ± 1.11 | 0.42 ± 1.43 | -0.896 | 0.370 |

| Abdominal pain syndrome | 0.60 ± 0.98 | 0.68 ± 1.51 | -1.283 | 0.196 |

| Dyspepsia | 1.71 ± 1.94 | 2.05 ± 2.86 | -0.362 | 0.717 |

| Diarrhea | 0.90 ± 1.07 | 1.44 ± 1.80 | -1.396 | 0.163 |

| Constipation | 0.88 ± 1.49 | 1.32 ± 2.15 | -1.027 | 0.304 |

| GSRS total score | 4.64 ± 4.36 | 5.90 ± 7.05 | -0.351 | 0.726 |

| After 8 weeks of intervention | ||||

| Reflux syndrome | 0.34 ± 1.21 | 0.33 ± 1.32 | -0.044 | 0.965 |

| Abdominal pain syndrome | 0.54 ± 1.13 | 0.74 ± 1.47 | -0.220 | 0.826 |

| Dyspepsia | 1.41 ± 1.81 | 1.97 ± 2.55 | -1.308 | 0.191 |

| Diarrhea | 0.85 ± 1.09 | 1.12 ± 1.74 | -0.009 | 0.314 |

| Constipation | 0.80 ± 1.38 | 1.05 ± 1.58 | -1.027 | 0.304 |

| GSRS total score | 3.94 ± 4.45 | 5.22 ± 6.26 | -1.096 | 0.273 |

Table 3 presents the changes in the gastrointestinal symptom scores of the study participants from baseline following the intervention. The results indicate that the total GSRS score and scores for all dimensions decreased significantly from preintervention levels at all observation time points after the intervention. After 2 weeks, the reduction in the reflux syndrome score was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the placebo-controlled group. After 4 weeks, the total GSRS score and the diarrhea syndrome score showed significantly greater reductions in the intervention group than in the placebo-controlled group. By 8 weeks, both the total GSRS score and the dyspepsia score were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo-controlled group. However, the reduction in the scores for the remaining dimensions did not reach statistical significance between the two groups.

| Variables | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | Z | P value |

| GSRS score after 2 weeks of intervention - baseline GSRS score | ||||

| Reflux syndrome2-0 | -3.06 ± 1.50 | -2.58 ± 1.26 | 2.243 | 0.025a |

| Abdominal pain syndrome2-0 | -1.25 ± 2.11 | -1.46 ± 2.68 | 0.016 | 0.987 |

| Dyspepsia2-0 | -3.00 ± 3.66 | -2.58 ± 3.17 | 0.801 | 0.423 |

| Diarrhea2-0 | -1.70 ± 3.74 | -1.87 ± 2.83 | -0.831 | 0.406 |

| Constipation2-0 | -1.62 ± 3.08 | -1.62 ± 2.93 | -0.164 | 0.870 |

| GSRS total score2-0 | -8.63 ± 9.54 | -8.11 ± 8.30 | 0.495 | 0.620 |

| GSRS score after 4 weeks of intervention - baseline GSRS score | ||||

| Reflux syndrome4-0 | -3.09 ± 1.41 | -2.64 ± 1.34 | -1.933 | 0.053 |

| Abdominal pain syndrome4-0 | -1.93 ± 2.39 | -1.58 ± 2.68 | -0.754 | 0.451 |

| Dyspepsia4-0 | -3.89 ± 3.87 | -2.45 ± 3.59 | -1.813 | 0.070 |

| Diarrhea4-0 | -2.90 ± 3.21 | -1.60 ± 2.77 | -2.458 | 0.014a |

| Constipation4-0 | -1.74 ± 2.54 | -1.14 ± 2.87 | -1.525 | 0.127 |

| GSRS total score4-0 | -13.55 ± 9.26 | -9.40 ± 8.46 | -2.356 | 0.018a |

| GSRS score after 8 weeks of intervention - baseline GSRS score | ||||

| Reflux syndrome8-0 | -3.00 ± 1.41 | -2.62 ± 1.64 | -1.365 | 0.172 |

| Abdominal pain syndrome8-0 | -2.02 ± 2.32 | -1.60 ± 3.04 | -1.350 | 0.177 |

| Dyspepsia8-0 | -4.19 ± 3.75 | -2.59 ± 3.20 | -2.381 | 0.017a |

| Diarrhea8-0 | -2.98 ± 3.31 | -1.83 ± 2.62 | -1.846 | 0.065 |

| Constipation8-0 | -1.87 ± 3.02 | -1.36 ± 3.00 | -1.316 | 0.188 |

| GSRS total score8-0 | -14.06 ± 9.32 | -10.00 ± 8.56 | -2.279 | 0.023a |

As shown in Table 4, the protective effect of probiotics on the occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms was not evident after 2 weeks of intervention. However, probiotics demonstrated a significant protective effect after both 4 and 8 weeks of intervention, reducing the incidence and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms more effectively than the placebo.

| Variables | Incidence of gastrointestinal reactions after 2 weeks of intervention (%) | Relative risk reduction (%) | Incidence of gastrointestinal reactions after 4 weeks of intervention (%) | Relative risk reduction (%) | Incidence of gastrointestinal reactions after 8 weeks of intervention (%) | Relative risk reduction (%) | |||

| Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | ||||

| Reflux syndrome | 37.8 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 7.1 | 59.2 |

| Abdominal pain syndrome | 48.8 | 48.1 | 0.01 | 12.9 | 14.8 | 12.8 | 8.7 | 16.9 | 48.5 |

| Dyspepsia | 74.4 | 70.9 | 0.05 | 34.3 | 37.9 | 9.5 | 26.1 | 36.6 | 28.7 |

| Diarrhea | 69.5 | 55.7 | 0.2 | 26.8 | 37.8 | 29.1 | 23.3 | 28.2 | 13.9 |

| Constipation | 39.0 | 34.2 | 0.1 | 18.6 | 21.6 | 13.9 | 13.1 | 17.0 | 22.9 |

As shown in Figure 2, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding the composition of stool types (constipated, normal, and diarrheal) after 2, 4, and 8 weeks of intervention. In the intervention group, the proportion of constipated stool initially decreased but then increased, ultimately falling below baseline levels after 8 weeks. Compared with that at baseline, the proportion of diarrheal stool decreased in both groups following the intervention, whereas the proportion of normal stool increased relative to the baseline level.

The results revealed that the eradication rate in the intervention group was 88.8%, whereas the eradication rate in the placebo-controlled group was 84.7%. The difference in eradication rates between the two groups was not statistically significant, as shown in Table 5.

| Variables | Intervention group (n = 89) | Placebo-controlled group (n = 85) | χ² | P value |

| Eradication rate | 79 (88.8) | 72 (84.7) | 0.790 | 0.430 |

During the first two weeks of the intervention, 5 participants in the intervention group and 9 participants in the control group did not adhere to the prescribed regimen for medication and probiotics or placebo. As a result, 93.9% of the participants in the intervention group and 88.6% of the participants in the control group followed the trial protocol during the first two weeks. By the fourth week of the intervention, 8 participants in the intervention group and 9 participants in the control group had not complied with the prescribed regimen. In total, 89.7% of the participants in the intervention group and 88.2% in the control group successfully completed the intervention protocol within the first four weeks, as shown in Table 6.

| Time points | Good compliance |

| After 2 weeks of intervention | |

| Intervention group (n = 82) | 77 (93.9) |

| Placebo-controlled group (n = 79) | 70 (88.6) |

| Total population (n = 161) | 147 (91.3) |

| After 4 weeks of intervention | |

| Intervention group (n = 78) | 70 (89.7) |

| Placebo-controlled group (n = 76) | 67 (88.2) |

| Total population (n = 154) | 137 (89.0) |

No serious adverse events were observed. Only two participants in the intervention group discontinued the intervention at week 4 because of mild abdominal distension and constipation; these symptoms were assessed by gastroenterologists as benign and resolved spontaneously within 1-2 days without any specific treatment. Other adverse events—including bitter taste, dizziness, headache, and rash—were uncommon and declined similarly in both groups, with no statistically significant between-group differences.

In this study, we observed that the administration of a multistrain probiotics preparation taken 2 hours after each dose of antibiotics significantly reduced the incidence of certain gastrointestinal symptoms and improved (GSRS scores during H. pylori eradication therapy. Furthermore, probiotics had a protective effect on gastrointestinal symptoms during H. pylori eradication without influencing H. pylori eradication rates.

Previous studies have demonstrated that supplementing standard H. pylori eradication regimens with probiotic preparations reduces gastrointestinal adverse effects, particularly diarrheal symptoms[8,18]. The results of the present study align with these findings, as both regimens with and without probiotics improved the occurrence of diarrhea syndrome in patients undergoing treatment. However, the improvement in reflux syndrome and dyspepsia symptoms was more pronounced in the intervention group than in the placebo-controlled group. The probiotic preparations used in this study consisted primarily of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp., both of which have been shown to ameliorate a variety of upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms[19]. This may explain the similarity between the results of this study and those of previous investigations. The positive effects of probiotics on gastrointestinal symptoms can increase patient compliance and improve the safety profile of eradication therapy, both of which are critical for the successful eradication of H. pylori. Additionally, the present study demonstrated a protective effect of probiotics on the occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms after 4 weeks of intervention, similar to findings reported by Niu et al[20], which may be attributed to the duration of probiotic use, with probiotics being administered for 2 weeks following the 14-day coadministration with bismuth-containing drugs. Although the precise mechanism by which probiotics improve gastrointestinal symptoms remains unclear, several potential mechanisms have been proposed: (1) Certain probiotic strains (e.g., Lactobacillus spp.) can colonize the stomach and directly or indirectly antagonize H. pylori[21-23]; (2) SCFAs produced by probiotics may reduce the urease activity of H. pylori and inhibit its colonization of the gastric mucosa[24]; and (3) Probiotics may inhibit interleukin-8-mediated inflammatory responses following H. pylori infection[25].

A study by Shi et al[26] found that multistrain probiotics treatment for H. pylori resulted in a high eradication rate and a low incidence of adverse effects, particularly with the combination of Lactobacillus and polymicrobial strains. However, the results of current studies regarding the effects of probiotic agents on H. pylori eradication rates remain inconsistent[26,27]. The present study did not observe any effect of the probiotic intervention on the H. pylori eradication rate. The findings of a multicenter randomized controlled trial conducted in China revealed that a mixed probiotic preparation containing Bifidobacterium bifidum, in combination with a bismuth quadruple regimen, failed to improve the H. pylori eradication rate[28], which is consistent with the results of this study. This may be attributed to the bismuth quadruple regimen used in the present study, which has been shown to reduce the concentration of H. pylori on its own[29], as well as its rapid antimicrobial effect on H. pylori and its synergistic interaction with certain antibiotics[30], which likely increases its efficacy. Therefore, the difference in eradication rates between the two groups was not statistically sig

In conclusion, this study revealed that a multistrain probiotics preparation, primarily composed of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum, effectively alleviated gastrointestinal symptoms during H. pylori eradication therapy. Probiotic supplementation demonstrated efficacy as an adjunct to bismuth-based quadruple therapy for H. pylori infection in adults. This study provides new evidence supporting the use of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium as adjuncts to quadruple therapy and preliminarily suggests that four weeks of probiotic supplementation may be beneficial. However, the ultimate goal of H. pylori research is to reduce the disease burden and improve eradication rates while increasing the gastrointestinal health of infected individuals. Therefore, further studies are needed to identify more effective probiotic strains, optimize dosage and timing regimens, and maximize their therapeutic potential. Additionally, factors such as the manufacturing process, stability (shelf life), and formulation type significantly influence the effectiveness of probiotic products[33]. Although probiotics are available in various formulations, including yogurt, fermented beverages, sachet powders, lyophilized capsules, and tablets, limited evidence comparing their relative efficacies exists[34]. Notably, only 25% of trials have examined probiotic use in quadruple therapy, limiting the ability to draw strong conclusions regarding multistrain probiotics combinations in this treatment context[19]. Future research should further explore the impact of probiotic formulations and specific strain combinations on H. pylori eradication efficacy.

This study used a rigorous randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate a mixed-strain probiotic preparation, which was primarily composed of five probiotic species, as an intervention. Probiotics were administered for four weeks within an eight-week intervention regimen, and outcome metrics were assessed at multiple time points: Baseline, two weeks, four weeks, and eight weeks. This design allowed for the evaluation of the dynamics of gast

However, this study has several limitations. First, as a single-center study conducted exclusively at the Department of Gastroenterology of Xiangya Hospital in Changsha, Hunan Province, China, there is a potential for selection bias. Additionally, geographical and population differences may limit the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, a two-month follow-up is insufficient to assess the long-term impact of probiotics-assisted BQT on the eradication of H. pylori and its broader impact on human health. Moreover, the low incidence of drug withdrawal due to mild gastrointestinal discomfort observed during the study (2/89, 2.2%) indicates good short-term tolerance. However, extended monitoring is also needed to confirm its safety and sustained efficacy. Third, the study assessed gastrointestinal symptoms from a macroscopic perspective without incorporating microbiological analyses, such as the intestinal microecological profile of patients. This limitation limits the ability to explore the precise mechanisms underlying the protective effects of probiotics on gastrointestinal symptoms. Future research could integrate animal models and histological techniques to address this gap. Fourth, none of the enrolled participants had received prior anti-H. pylori treatment; therefore, the effect of this multistrain probiotics in patients with prior eradication failure was not assessed and warrants future investigation. Finally, the probiotic strains and supplementation regimens used in this study were not definitively superior to other available formulations. Given that different probiotic compositions and strain combinations exhibit varying efficacies in H. pylori eradication, this variability may have influenced the accuracy of the study’s findings. Further research is needed to determine the optimal probiotic strains, supplementation regimens, and timing to effectively increase H. pylori eradication rates.

In this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, a four-week multistrain probiotics containing Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species significantly alleviated reflux, dyspepsia and diarrhoea symptoms associated with bismuth quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication, with benefits emerging after four weeks and persisting to eight weeks. No improvement in eradication rates was observed. The intervention is safe, well tolerated and can be recommended as an adjunct to enhance patient comfort and adherence during standard eradication regimens.

We sincerely thank the faculty and students of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, China, for their valuable contributions to this study. We also extend our gratitude to the faculty and leadership of Xiangya Hospital for their support. Finally, we deeply appreciate all the study participants for their time and cooperation.

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3302] [Cited by in RCA: 3314] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Chen YC, Malfertheiner P, Yu HT, Kuo CL, Chang YY, Meng FT, Wu YX, Hsiao JL, Chen MJ, Lin KP, Wu CY, Lin JT, O'Morain C, Megraud F, Lee WC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS, Liou JM. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Incidence of Gastric Cancer Between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology. 2024;166:605-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 140.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1475] [Cited by in RCA: 1267] [Article Influence: 115.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, Marshall JK. The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:51-69.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 695] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 2089] [Article Influence: 232.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Mathers C, Forman D, Bray F. Global burden of cancer in 2008: a systematic analysis of disability-adjusted life-years in 12 world regions. Lancet. 2012;380:1840-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pourmasoumi M, Najafgholizadeh A, Hadi A, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F. The effect of synbiotics in improving Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;43:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Homan M, Orel R. Are probiotics useful in Helicobacter pylori eradication? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10644-10653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Eslami M, Yousefi B, Kokhaei P, Jazayeri Moghadas A, Sadighi Moghadam B, Arabkari V, Niazi Z. Are probiotics useful for therapy of Helicobacter pylori diseases? Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;64:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 1071] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Lionetti E, Indrio F, Pavone L, Borrelli G, Cavallo L, Francavilla R. Role of probiotics in pediatric patients with Helicobacter pylori infection: a comprehensive review of the literature. Helicobacter. 2010;15:79-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hauser G, Salkic N, Vukelic K, JajacKnez A, Stimac D. Probiotics for standard triple Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Linsalata M, Russo F, Berloco P, Caruso ML, Matteo GD, Cifone MG, Simone CD, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. The influence of Lactobacillus brevis on ornithine decarboxylase activity and polyamine profiles in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Helicobacter. 2004;9:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim MN, Kim N, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Lee DH, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. The effects of probiotics on PPI-triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2008;13:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Wilhelm SM, Johnson JL, Kale-Pradhan PB. Treating bugs with bugs: the role of probiotics as adjunctive therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:960-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vítor JM, Vale FF. Alternative therapies for Helicobacter pylori: probiotics and phytomedicine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63:153-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang Z, Zhou Y, Han Z, He K, Zhang Y, Wu D, Chen H. The effects of probiotics supplementation on Helicobacter pylori standard treatment: an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Sci Rep. 2024;14:10069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McFarland LV, Huang Y, Wang L, Malfertheiner P. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Multi-strain probiotics as adjunct therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication and prevention of adverse events. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:546-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | de Milliano I, Tabbers MM, van der Post JA, Benninga MA. Is a multispecies probiotic mixture effective in constipation during pregnancy? 'A pilot study'. Nutr J. 2012;11:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Niu Y, Li J, Qian H, Liang C, Shi X, Bu S. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LRa05 in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1450414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta SP, Magistà AM, Maurogiovanni G, Bucci N, De Canio A, Indrio F, Cavallo L, Ierardi E, Miniello VL. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection in humans by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and effect on eradication therapy: a pilot study. Helicobacter. 2008;13:127-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Espinoza JL, Matsumoto A, Tanaka H, Matsumura I. Gastric microbiota: An emerging player in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ryan KA, Jayaraman T, Daly P, Canchaya C, Curran S, Fang F, Quigley EM, O'Toole PW. Isolation of lactobacilli with probiotic properties from the human stomach. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mukai T, Asasaka T, Sato E, Mori K, Matsumoto M, Ohori H. Inhibition of binding of Helicobacter pylori to the glycolipid receptors by probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;32:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Panpetch W, Spinler JK, Versalovic J, Tumwasorn S. Characterization of Lactobacillus salivarius strains B37 and B60 capable of inhibiting IL-8 production in Helicobacter pylori-stimulated gastric epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shi X, Zhang J, Mo L, Shi J, Qin M, Huang X. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in eradicating Helicobacter pylori: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Navarro-Rodriguez T, Silva FM, Barbuti RC, Mattar R, Moraes-Filho JP, de Oliveira MN, Bogsan CS, Chinzon D, Eisig JN. Association of a probiotic to a Helicobacter pylori eradication regimen does not increase efficacy or decreases the adverse effects of the treatment: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | He C, Xie Y, Zhu Y, Zhuang K, Huo L, Yu Y, Guo Q, Shu X, Xiong Z, Zhang Z, Lyu B, Lu N. Probiotics modulate gastrointestinal microbiota after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1033063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | McLaren A, Donnelly C, McDowell S, Williamson R. The role of ranitidine bismuth citrate in significantly reducing the emergence of Helicobacter pylori strains resistant to antibiotics. Helicobacter. 1997;2:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dore MP, Lu H, Graham DY. Role of bismuth in improving Helicobacter pylori eradication with triple therapy. Gut. 2016;65:870-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Viazis N, Argyriou K, Kotzampassi K, Christodoulou DK, Apostolopoulos P, Georgopoulos SD, Liatsos C, Giouleme O, Koustenis K, Veretanos C, Stogiannou D, Moutzoukis M, Poutakidis C, Mylonas II, Tseti I, Mantzaris GJ. A Four-Probiotics Regimen Combined with A Standard Helicobacter pylori-Eradication Treatment Reduces Side Effects and Increases Eradication Rates. Nutrients. 2022;14:632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pantoflickova D, Corthésy-Theulaz I, Dorta G, Stolte M, Isler P, Rochat F, Enslen M, Blum AL. Favourable effect of regular intake of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus johnsonii on Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:805-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sanders ME, Klaenhammer TR, Ouwehand AC, Pot B, Johansen E, Heimbach JT, Marco ML, Tennilä J, Ross RP, Franz C, Pagé N, Pridmore RD, Leyer G, Salminen S, Charbonneau D, Call E, Lenoir-Wijnkoop I. Effects of genetic, processing, or product formulation changes on efficacy and safety of probiotics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1309:1-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sniffen JC, McFarland LV, Evans CT, Goldstein EJC. Choosing an appropriate probiotic product for your patient: An evidence-based practical guide. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/