Published online Jan 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i3.95871

Revised: October 29, 2024

Accepted: November 26, 2024

Published online: January 21, 2025

Processing time: 242 Days and 22.1 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a prevalent disease encountered in military internal medicine and recognized as the main cause of dyspepsia, gastritis, and peptic ulcer, which are common diseases in military personnel. Current guidelines in China state all patients with evidence of active infection with H. pylori are offered treatment. However, the prevalence of H. pylori infection and its regional distribution in the military population remain unclear, which hinders effective prevention and treatment strategies. Understanding the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the military population will aid in the development of customized strategies to better manage this infectious disease.

To investigate the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Chinese military population in different geographic areas.

This multicenter, retrospective study included 22421 individuals from five tertiary hospitals located in north, east, southwest, and northwest cities of China. H. pylori infection was identified using the urea breath test, which had been performed between January 2020 and December 2021.

Of the 22421 military service members, 7416 (33.1%) were urea breath test-positive. The highest prevalence of H. pylori was in the 30-39 years age group for military personnel, with an infection rate of 34.9%. The majority of infected subjects were younger than 40-years-old, accounting for 70.4% of the infected population. The individuals serviced in Lanzhou and Chengdu showed a higher infection prevalence than those in Beijing, Nanjing, and Guangzhou, with prevalence rates of 44.3%, 37.9%, 29.0%, 31.1%, and 32.3%, respectively.

H. pylori infection remains a common infectious disease among military personnel in China and has a relatively high prevalence rate in northwest China.

Core Tip: This multicenter, retrospective study included 22421 participants from five tertiary hospitals located in north, east, southwest, and northwest China and investigated the current prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Chinese military personnel. The H. pylori infection rate was 33.1%, and the highest prevalence of H. pylori was in the 30-39 years age group. Among military service members, 70.4% of the infected personnel were aged < 40 years. The individuals stationed in Lanzhou and Chengdu showed a higher infection prevalence than those stationed in Beijing, Nanjing, and Guangzhou, with prevalence rates of 44.3%, 37.9%, 29.0%, 31.1%, and 32.3%, respectively.

- Citation: Min HC, Zhang CY, Wang FY, Yu XH, Tang SH, Zhu HW, Zhao YG, Liu JL, Wang J, Guo JH, Zhang XM, Yang YS. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese military personnel: A cross-sectional, multicenter-based study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(3): 95871

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i3/95871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i3.95871

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is estimated to affect approximately 50% of the world’s population, with approximately 4.4 billion individuals infected with H. pylori worldwide[1]. Its prevalence varies considerably with respect to geographical location, economic development, age, ethnicity, health habits, and population lifestyles. The prevalence tends to be low in developed countries (30.2%-39.3%) and high in developing countries (46.8%-54.7%)[2-4]. A continuous decrease in H. pylori prevalence has been reported in many countries, including Korea[5], Iran[6], Austria[7], and China[2,8]. A systematic review showed that the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in mainland China has been decreasing over the past few decades. Specifically, the infection rate decreased from 58.3% in 1983-1994 to 40.0% in 2015-2019[2]. However, H. pylori infection remains a high-risk factor and a heavy burden in China, and there have been extensive variations in the prevalence of H. pylori infection across different regions. The prevalence was relatively high in the southwest (51.8%) and northwest (46.6%) regions, which could be related to lower economic living standards, unhealthy living habits, and poor environmental factors[2].

Risk factors for H. pylori infection include smoking, occupational risk factors, water supply, food, age, drinking, socioeconomic status, and living environment[3,9]. Since different occupations may represent distinct pathways for acquiring the infection, it is reasonable to assume that it could be much more contagious in closed communities, i.e., among military service members than in the civilian population. H. pylori infection is a common and significant problem in military internal medicine and is recognized as the main cause of dyspepsia, gastritis, and peptic ulcer disease, which are very common in the military population.

Current guidelines, including the recently published “Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report”[10], “Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis”[11], and “Sixth Chinese national consensus report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection” recommend eradicating H. pylori infection unless there are competing considerations[12]. However, evidence on the prevalence of H. pylori infection and its regional variation, particularly from large-scale and multiregional investigations in the military population, is scarce, hindering the establishment of effective prevention and treatment strategies for military personnel.

Moreover, most studies were conducted in the 1990s. Studies from other countries have reported a lower prevalence of infection in military population than in the general population[9]. A recent single hospital-based study in Shenyang, northeast China, showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in military service members was 33.9%, which was similar to that in the civilian population[13]. Furthermore, among the population aged 17-25 years, the infection rate was much higher in the military group than in the civilian group (35.6% vs 25.9%)[13]. Understanding the prevalence of H. pylori infection and its regional variation in the military population will aid in the development of customized strategies to better manage this infectious disease, with the premise of up-to-date information. The study presented herein aimed to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection in military servicemen with a large sample from five tertiary hospitals located in the northwest, southeast, north, south, and southwest cities of China to help establish strategies for the prevention and eradication of H. pylori infection and related diseases in military servicemen.

This multicenter, retrospective study was performed in five tertiary hospitals in China, including Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital in Beijing, General Hospital of Eastern Theater Command in Nanjing, General Hospital of Western Theater Command in Chengdu, General Hospital of Southern Theater Command in Guangzhou, and the 940th Hospital of Joint Logistic Support Force of Chinese People’s Liberation Army in Lanzhou. H. pylori infection was identified by the urea breath test (UBT), which was performed between January 2020 and December 2021. The identity of eligible participants was recognized as military personnel based on their unique identity document numbers obtained from the electronic medical record system.

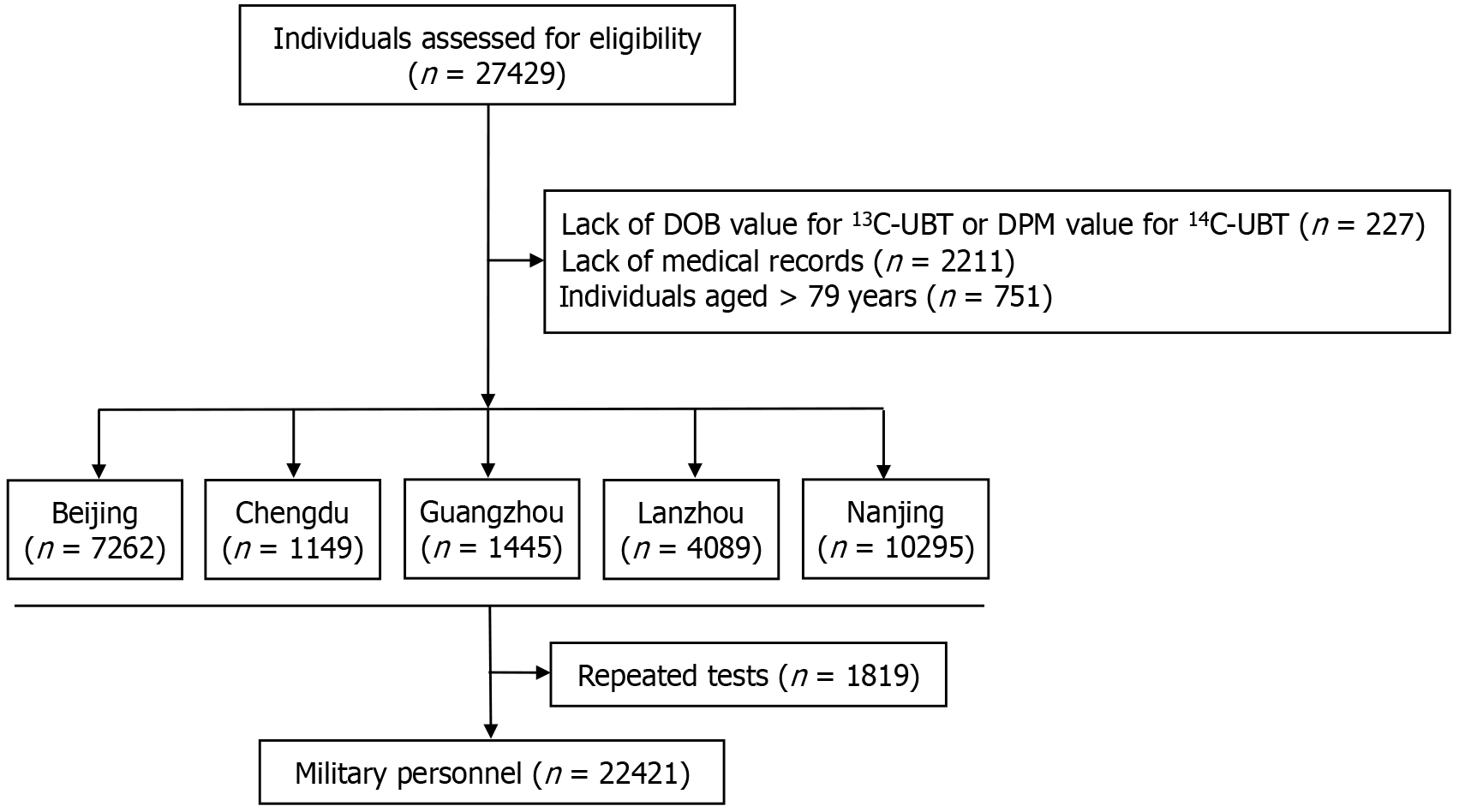

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Lack of the disintegrations per minute (DPM) values for 14C-UBT or the delta-over-baseline (DOB) values for 13C-UBT; (2) Individuals aged > 79 years; (3) Missing information on demographics and/or individuals’ identity records; and (4) Repeated UBTs performed in the same individual. We primarily collected information regarding demographics (i.e., age and sex) and H. pylori infection status. This study was a retrospective study and did not obtain consent from all the patients. We had applied for a waiver of the informed consent form, and it was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (Approval No. S2022-358-01).

The UBT, including 13C and 14C, was used to identify H. pylori infection status. 13C-UBT was performed after an overnight fast. The baseline exhaled breath samples were collected by blowing through a disposable plastic straw into a CO2 storage container. Then, patients were instructed to ingest the test meal with 75 mg of 13C-urea dissolved in 100 mL of water. Further, breath samples were collected 30 minutes after ingestion of the tracer. Breath samples were subjected to infrared spectroscopy for H. pylori detection. The results were presented as DOB values. According to the manufacturer, a DOB ≥ 4% indicates a diagnosis of H. pylori infection.

14C-UBT was performed after an overnight fast. Patients were instructed to take a 14C-urea (27.8 kBq) capsule with warm water. Breath samples were collected in a special bottle containing CO2 gas collector 15 minutes after ingestion. Each breath sample was trapped in a 4.5 mL diluted scintillation solution. 14C content was measured in DPM mode using a liquid beta-scintillation counter. A cutoff value of 100 was set for the positive test result.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age, sex, and region. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 22421 individuals were included after excluding 227 cases lacking DOB values for 13C-UBT or DPM values for 14C-UBT, 2211 cases lacking medical records, 751 individuals older than 79 years, and 1819 cases with repeated tests (Figure 1). The ratio of males to females in the military group was 4.3:1. The majority of individuals were younger than 40-years-old, with 28.1% in the 18-29 years age group and 39.3% in the 30-39 years age group. The number of subjects collected from Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, Lanzhou, and Nanjing were 6659, 1048, 1348, 3771, and 9595, respectively (Table 1).

| Characteristic | n | % |

| Total | 22421 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 4263 | 19.0 |

| Male | 18158 | 81.0 |

| Age group in year | ||

| 18-29 | 6301 | 28.1 |

| 30-39 | 8818 | 39.3 |

| 40-49 | 3487 | 15.6 |

| 50-59 | 2244 | 10.0 |

| 60-69 | 1138 | 5.1 |

| 70-79 | 433 | 1.9 |

| Hospital location | ||

| Beijing | 6659 | 29.7 |

| Chengdu | 1048 | 4.7 |

| Guangzhou | 1348 | 6.0 |

| Lanzhou | 3771 | 16.8 |

| Nanjing | 9595 | 42.8 |

Overall prevalence in the military personnel: Among the 22421 military cases, 7416 cases were UBT-positive, with an infection rate of 33.1%. No significant differences were observed between males and females (Table 2).

| Parameter | Prevalence, % (n/total) | P value |

| Total | 33.1 (7416/22421) | |

| Sex | 0.771 | |

| Male | 33.1 (6014/18158) | |

| Female | 32.9 (1402/4263) | |

| Age group in year | < 0.001 | |

| 18-29 | 33.9 (2137/6301) | |

| 30-39 | 34.9 (3080/8818) | |

| 40-49 | 31.8 (1108/3487) | |

| 50-59 | 29.6 (664/2244) | |

| 60-69 | 26.2 (298/1138) | |

| 70-79 | 29.8 (129/433) | |

| Hospital location | < 0.001 | |

| Beijing | 29.0 (1929/6659) | |

| Chengdu | 37.9 (397/1048) | |

| Guangzhou | 32.3 (435/1348) | |

| Lanzhou | 44.3 (1671/3771) | |

| Nanjing | 31.1 (2984/9595) |

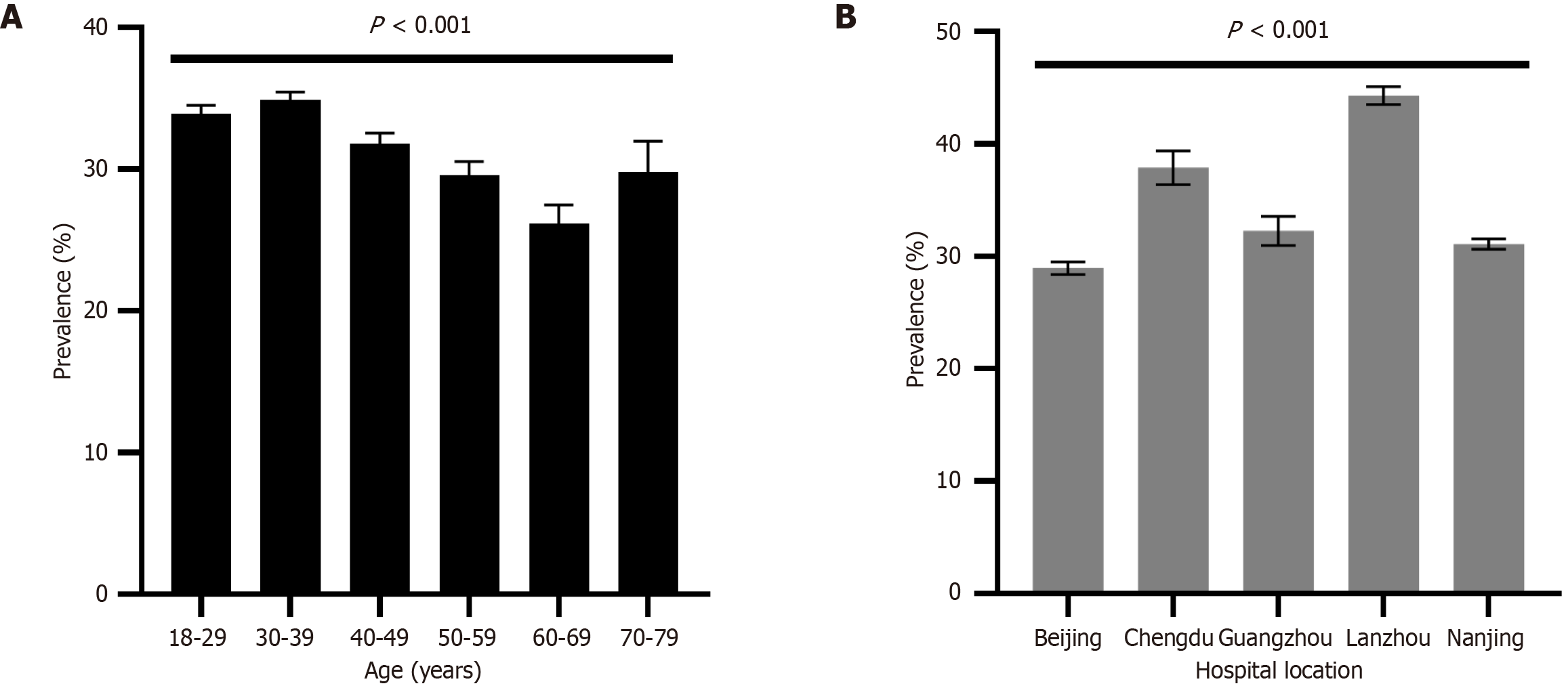

Age demographics and H. pylori infection: The highest prevalence of H. pylori was in the age group of 30-39 years for military personnel, with infection rates of 34.9%, followed by the age groups of 18-29 years (33.9%), 40-49 years (31.8%), 50-59 years (29.6%), and 60-69 years (26.2%) (Figure 2A).

H. pylori prevalence in different regions: Among military personnel, Lanzhou had the highest prevalence, followed by Chengdu (44.3% and 37.9%, respectively). On the contrary, Beijing, Nanjing, and Guangzhou were among the areas with lower prevalence (29.0%, 31.1%, and 32.3%, respectively) (Figure 2B).

A cross-sectional, multicenter-based study was conducted to investigate the prevalence of H. pylori infection among military service members in China. Patients from five participating hospitals located in north, east, south, southwest, and northwest China and the military members of active-duty service in combat and non-combat army were included. The H. pylori infection rate in the military group was 33.1% in our study.

There remains a high H. pylori infection rate in the Chinese army, especially when approximately 70% of the infected individuals are under the age of 40, which is an important part of the insurance of their health and effectiveness. Based on the data of this study, we infer that the actual prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Chinese military population should be lower than that found in this study because this was a hospital-based study, and most individuals were patients with gastrointestinal complaints. In line with most other studies, we showed that individuals from the armed forces had a lower prevalence of infection than the general population of the same country[9,14]. This result may be explained by the fact that most individuals in the military group were in the younger age group.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in military populations varies among countries. The prevalence obtained in our study was higher than that reported in other countries; H. pylori seropositivity rate was 26.3% in army recruits in the United States[15], 33% in male recruits in Hungary[16], and 19.01% in navy recruits in Greece[17]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 32% in military personnel, with a lower rate of 19.9% in North America and 21.1% in Europe and a higher rate of 50.2% in Asia[18]. This rate may be related to the overall prevalence in the civilian population, national socioeconomic conditions, and military environment.

Although we could not obtain the exact risk factors for infection in the military population from the five hospitals by the retrospective data analysis, geographical location was found to be the important factor related with the infection rate. The data from the 940th Hospital in Lanzhou showed that the prevalence was 44.3%, followed by 37.9% prevalence from the General Hospital of Western Theater Command in Chengdu. These two hospitals are located in the northwest and southwest regions of China, which have a low socioeconomic status. In contrast, in economically developed areas, such as Beijing (29.0%), Nanjing (31.1%), and Guangzhou (32.3%), the infection rate was relatively low. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis showed that the infection rate of H. pylori among the civilian population in China was relatively high in the northwest and southwest regions, which could be related to the lower economic living standards and poor environmental factors[19].

Among military service members with no significant difference in economic income in different regions, it is rea

In our study, infection rates in military personnel were not different between sexes, which may be attributed to the relatively small sample size of females. Considering age stratification, up to 70% of the patients who were H. pylori-positive were younger than 40 years. The proportion of soldiers or combat personnel is high among young recruits, and most lived in remote areas with poor sanitary environments and shared the same dormitory in barracks, which may have increased H. pylori infection and transmission. Young military personnel have more frequent high-intensity military activities, which may increase the risk of H. pylori infections[23]. In this study, a lower infection rate was found in the elder group, which may be related due to this group serving as non-combat personnel with better sanitary conditions or some individuals having received H. pylori eradication in time during their routine health check.

Considering age-stratified prevalence, our study found that people aged 30-39 years had the highest infection rate, consistent with a study assessing prevalence in a region with high-risk for gastric cancer[24,25]. However, it was inconsistent with other studies suggesting that infection rate gradually increases with age[2]. This may be attributed to different populations of subjects. This study was performed among military personnel, and they are mainly young and middle-aged, having a different age structure than the general population. This may also be attributed to different methods for evaluating prevalence, as UBT was used in our study and seroprevalence or stool antigen was used in other studies. Our study used 13C-UBT and 14C-UBT to investigate the prevalence of H. pylori. These two methods do not differ in sensitivity and specificity and have good performance for diagnosis and reflecting the current infection of H. pylori[26]. However, serum H. pylori antibodies may exist for a long period even after eradication therapy. Many older adults may show a negative status on UBT for reduced gastric acid secretion, and others may experience an unintentional eradication from using antibiotics.

This study had some limitations. First, in contrast to the epidemiological sampling survey, this study was based on a data set from hospitals, and individuals included were patients with gastrointestinal complaints. Therefore, the infection rate obtained in this study may have been higher than that obtained in an epidemiological survey. Second, the UBT used in this study may have led to false-negative results in patients with a history of use of antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors, or bismuth[27]. However, this proportion is extremely low because these hospitals are large tertiary hospitals, and detection was carried out according to standard procedures, including the question of medication history before the test. Third, due to the retrospective design of the study, some information, such as H. pylori infection eradication history and detailed personal information, could not be accurately tracked through electronic medical records, and the risk factors for infection were not considered. Lastly, we could not distinguish between soldiers, officers, and combat and non-combat personnel. Thus, comparison data among rank groups could not be obtained. In the future, we plan to conduct pro

H. pylori infection has a high prevalence among Chinese military service members, affecting more than one-third of the military personnel. More than 70% of the infected personnel were aged < 40 years. There was a relatively high prevalence rate in northwest and southwest China. Ongoing efforts to control H. pylori infection are crucial in military internal medicine to reduce the incidence of digestive ulcers, dyspepsia, gastric precancerous lesions, and cancer. This study’s findings offer a significant foundation for allocating healthcare resources and developing H. pylori eradication strategies appropriate for military personnel.

| 1. | Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 2208] [Article Influence: 245.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Ren S, Cai P, Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, Li Q, Gu Y, Wei L, Yan C, Jin G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | Leja M, Grinberga-Derica I, Bilgilier C, Steininger C. Review: Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2019;24 Suppl 1:e12635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, Derakhshan MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:868-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 66.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lim SH, Kim N, Kwon JW, Kim SE, Baik GH, Lee JY, Park KS, Shin JE, Song HJ, Myung DS, Choi SC, Kim HJ, Yim JY, Kim JS. Trends in the seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and its putative eradication rate over 18 years in Korea: A cross-sectional nationwide multicenter study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maleki I, Mohammadpour M, Zarrinpour N, Khabazi M, Mohammadpour RA. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Sari Northern Iran; a population based study. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2019;12:31-37. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kamogawa-Schifter Y, Yamaoka Y, Uchida T, Beer A, Tribl B, Schöniger-Hekele M, Trauner M, Dolak W. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and its CagA subtypes in gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer at an Austrian tertiary referral center over 25 years. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yu X, Yang X, Yang T, Dong Q, Wang L, Feng L. Decreasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori according to birth cohorts in urban China. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kheyre H, Morais S, Ferro A, Costa AR, Norton P, Lunet N, Peleteiro B. The occupational risk of Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91:657-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O'Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 210.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1475] [Cited by in RCA: 1263] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Helicobacter pylori Study Group; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; Chinese Medical Association. [Sixth Chinese national consensus report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection (treatment excluded)]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2022;42:289-303. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Wang C, Liu J, Shi X, Ma S, Xu G, Liu T, Xu T, Huang B, Qu Y, Guo X, Qi X. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Military Personnel from Northeast China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1499-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pateraki E, Mentis A, Spiliadis C, Sophianos D, Stergiatou I, Skandalis N, Weir DM. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Greece. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1990;2:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Smoak BL, Kelley PW, Taylor DN. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections in a cohort of US Army recruits. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fürész J, Lakatos S, Németh K, Fritz P, Simon L, Kacserka K. The prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infections among young recruits during service in the Hungarian Army. Helicobacter. 2004;9:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kyriazanos I, Ilias I, Lazaris G, Hountis P, Deros I, Dafnopoulou A, Datsakis K. A cohort study on Helicobacter pylori serology before and after induction in the Hellenic Navy. Mil Med. 2001;166:411-415. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wang C, Liu J, An Y, Zhang D, Ma R, Guo X, Qi X. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in military personnel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Hyams KC, Taylor DN, Gray GC, Knowles JB, Hawkins R, Malone JD. The risk of Helicobacter pylori infection among U.S. military personnel deployed outside the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Taylor DN, Sanchez JL, Smoak BL, DeFraites R. Helicobacter pylori infection in Desert Storm troops. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:979-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou XZ, Lyu NH, Zhu HY, Cai QC, Kong XY, Xie P, Zhou LY, Ding SZ, Li ZS, Du YQ; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Large-scale, national, family-based epidemiological study on Helicobacter pylori infection in China: the time to change practice for related disease prevention. Gut. 2023;72:855-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jia K, An L, Wang F, Shi L, Ran X, Wang X, He Z, Chen J. Aggravation of Helicobacter pylori stomach infections in stressed military recruits. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:367-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang F, Pu K, Wu Z, Zhang Z, Liu X, Chen Z, Ye Y, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Zhang J, An F, Zhao S, Hu X, Li Y, Li Q, Liu M, Lu H, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Yuan H, Ding X, Shu X, Ren Q, Gou X, Hu Z, Wang J, Wang Y, Guan Q, Guo Q, Ji R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and associated risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Wuwei cohort of north-western China. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26:290-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang X, Shu X, Li Q, Li Y, Chen Z, Wang Y, Pu K, Zheng Y, Ye Y, Liu M, Ma L, Zhang Z, Wu Z, Zhang F, Guo Q, Ji R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Wuwei, a high-risk area for gastric cancer in northwest China: An all-ages population-based cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, Madani W, Firwana B, Hasan R, Altayar O, Limburg PJ, Murad MH, Knawy B. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1305-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 27. | Patel SK, Pratap CB, Jain AK, Gulati AK, Nath G. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: what should be the gold standard? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12847-12859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/