Published online Feb 7, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i5.462

Peer-review started: November 1, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Revised: December 19, 2023

Accepted: January 11, 2024

Article in press: January 11, 2024

Published online: February 7, 2024

Processing time: 90 Days and 14 Hours

Some hydatid cysts of cystic echinococcosis type 1 (CE1) lack well-defined cyst walls or distinctive endocysts, making them difficult to differentiate from simple hepatic cysts.

To investigate the diagnostic methods for atypical hepatic CE1 and the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic surgeries.

The clinical data of 93 patients who had a history of visiting endemic areas of CE and were diagnosed with cystic liver lesions for the first time at the People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (China) from January 2018 to September 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical diagnoses were made based on findings from serum immunoglobulin tests for echinococcosis, routine abdominal ultrasound, high-frequency ultrasound, abdominal computed tomo

All 93 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by conventional abdominal ultrasound and abdominal CT scan. Among them, 16 patients were preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1, and 77 were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by high-frequency ultrasound. All the 16 patients preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1 underwent laparoscopy, of whom 14 patients were intraoperatively confirmed to have CE1, which was consistent with the postope

Abdominal high-frequency ultrasound can detect CE1 hydatid cysts. The laparoscopic technique serves as a more effective diagnostic and therapeutic tool for CE.

Core Tip: This retrospective study investigated the diagnostic methods for atypical hepatic cystic echinococcosis type 1 (CE1) and evaluated the clinical efficacy of laparoscopic surgeries. In total, 93 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by conventional abdominal ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography scan. Among them, 16 patients were preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1, of whom 14 were diagnosed with CE1 intraoperatively after laparoscopy. The remaining 77 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by high-frequency ultrasound, of whom 4 patients received aspiration sclerotherapy of hepatic cysts, and 19 patients were intraoperatively diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts. Abdominal high-frequency ultrasound can detect CE1 hydatid cysts.

- Citation: Li YP, Zhang J, Li ZD, Ma C, Tian GL, Meng Y, Chen X, Ma ZG. Diagnosis and treatment experience of atypical hepatic cystic echinococcosis type 1 at a tertiary center in China. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(5): 462-470

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i5/462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i5.462

Humans can be affected by hepatic hydatid disease, also known as hepatic echinococcosis, by ingesting eggs from Echinococcus granulosus through eating contaminated food products[1]. Along with developments in animal husbandry and tourism, hepatic echinococcosis has become a worldwide epidemic disease that threatens public health and hinders social progress. Surveys organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations indicated that alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis are the second and third most common foodborne parasitic diseases, respectively[2,3]. The average prevalence of echinococcosis is 1.08% among the population in western China. Globally, the disease affects approximately 66 million people, resulting in an annual economic loss of around 400 million US dollars[4]. Echinococcosis may further aggravate the economic burden in low-income regions. Early-stage hepatic echinococcosis lacks specific clinical symptoms. Some patients may have already missed the opportunity of treatment at the time of diagnosis, leading to a marked deterioration in their quality of life and premature death[5-7]. In endemic areas of hepatic echinococcosis, surgery is the most effective treatment[8]. Given the distinct biological features of this disease, only a few patients with hepatic echinococcosis can receive standardized diagnosis and treatment. This explains the high incidence of complications and high recurrence rate of hepatic echinococcosis, further increasing the likelihood of repeated surgeries. The WHO-Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO/IWGE) divided cystic echinococcosis (CE) into six types (WHO classification)[9]. CE type 1 (CE1) is defined as a unilocular anechoic cystic lesion, presenting with a hydatid cyst wall and an endocyst that are distinctly demarcated from the surrounding liver tissues. However, some patients with CE1 exhibit atypical clinical manifestations, and findings from laboratory tests and radiographic examinations may not align with typical patterns. In specific cases of CE1, hydatid cysts may lack clearly defined cyst walls or characteristic endocysts. It is challenging to differentiate these lesions from simple hepatic cysts. Erroneous diagnosis and treatment of atypical CE1 may lead to grim consequences[10]. For instance, some atypical CE1 lesions are misdiagnosed and surgically treated as simple hepatic cysts, resulting in the spillage of hydatid fluid, or even anaphylactic shock and death. Developing appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for atypical CE1 hydatid cysts is of great importance.

In the present study, a high-frequency linear array transducer (5.0-12 MHz) was utilized to scan patients with a history of visiting CE endemic areas. The patients were diagnosed with hepatic cysts by conventional abdominal ultrasound (convex array probe, 3.5-5.0 MHz) and abdominal computed tomography (CT). The purpose was to improve the diagnostic rate of atypical CE1. Laparoscopic procedures were performed to verify the diagnosis of atypical CE1 and to deliver a less invasive treatment, in order to reduce the misdiagnosis rate and the risks associated with potential delays in treatment.

From January 2018 to September 2023, 93 patients received treatments for simple hepatic cysts at the People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Urumqi, China). All patients had a history of visiting CE endemic areas. Fur

Medical history inquiry, physical examinations, and laboratory tests: The main complaints and findings from physical and abdominal examinations were collected. The results of routine blood tests, liver function tests, tumor marker tests, and serum immunoglobulin tests for echinococcosis (colloidal gold-based immunochromatographic strip assay, Colloidal Gold Diagnostic Kit for Echinococcosis by Xinjiang Hydatid Clinical Research Institute, China) were obtained.

Radiographic examinations: Ultrasound scan was performed using the GE LOGIQ E9 ultrasound scanner (GE HealthCare Technologies, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and the Philips iu22 ultrasound machine (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands), with a convex array probe for conventional abdominal ultrasound (3.5-5.0 MHz). Upon discovery of hepatic cystic lesions, we changed the convex array probe to the high-frequency linear array transducer (5.0-12 MHz), which allowed for a multi-directional observation of whether the cystic lesion had localized cyst wall thickening or a bilayered wall. If the high-frequency linear array transducer only delivered a limited penetrating power, there would be a change back to the convex array transducer for local magnification to observe whether there was a bilayered wall or local cyst wall thickening.

Abdominal CT scanning was carried out using the Philips 128-slice spiral CT scanner, with a slice thickness of 3 mm and a spacing of 5 mm. Before CT scanning, the patient drank 1000-1500 mL clear water and lay on their back. The CT was performed in the supine position to observe whether the upper and lower layers of the cyst fluid in the simple hepatic lesions had uneven density.

Patients identified with distinctive signs of hepatic cystic lesions using color Doppler ultrasound, and subsequently diagnosed with atypical CE1, underwent laparoscopic exploration to determine the optimal surgical approach.

Patients received laparotomic/laparoscopic endocystectomy plus partial ectocystectomy or laparotomic/laparoscopic cystectomy if they met the following conditions: (1) The average hydatid cyst diameter was > 5 cm; (2) The average hydatid cyst diameter was ≤ 5 cm , and the lesion was located in the first and second hepatic hila; and (3) The average hydatid cyst diameter was ≤ 5 cm , and patients could not tolerate medication or had poor medication compliance or were unable to tolerate percutaneous-aspiration-injection-reaspiration (PAIR).

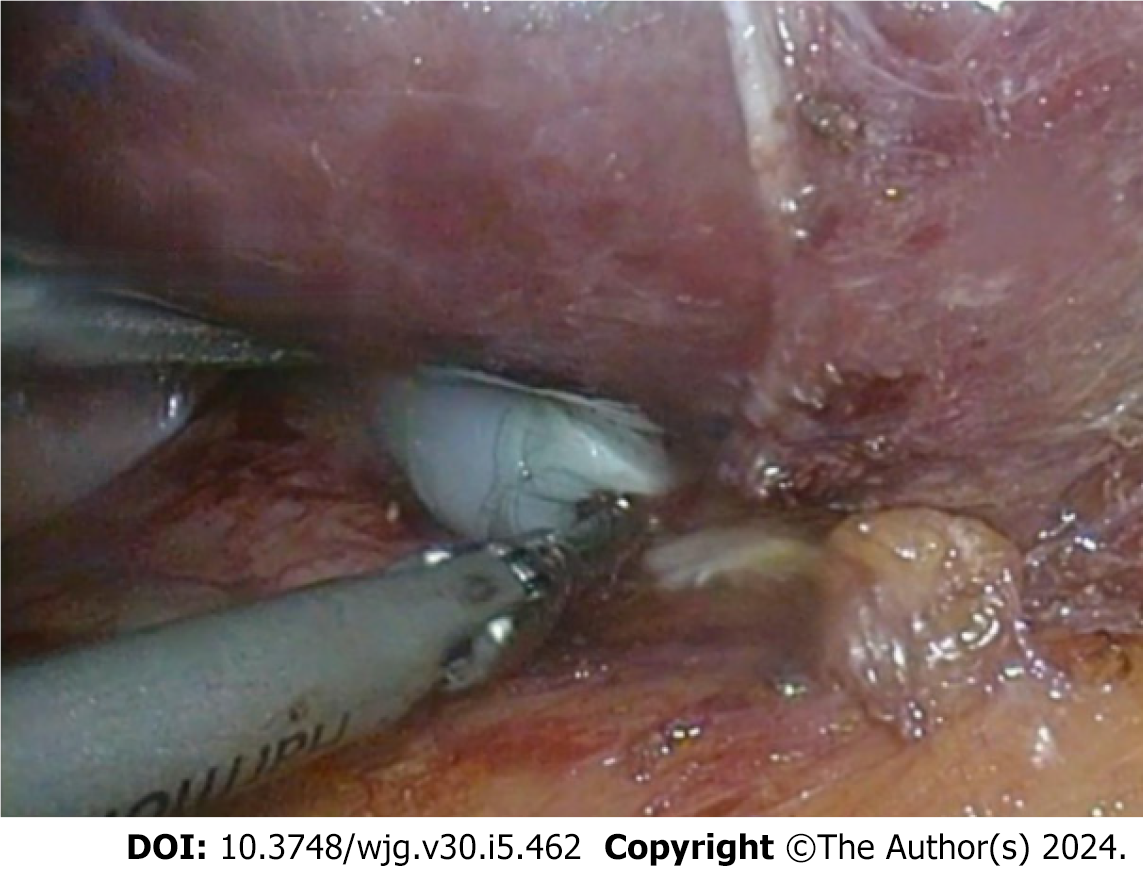

Laparoscopic endocystectomy plus partial or intact ectocystectomy was performed as follows: After general anesthesia, a prophylactic intravenous injection of 100 mg of hydrocortisone was given to prevent allergy. The pneumoperitoneum pressure was 10-12 mmHg. Five trocars were placed in the abdominal wall, with the observing trocar situated above the umbilicus and the operating trocars arranged in a fan-shaped pattern, concentrating on the lesion at the center. Gauze soaked with hypertonic saline (20%) was placed around the hydatid cysts to isolate them from abdominal organs. For lesions with thin-walled ectocysts and high tension, aspiration was carried out at the highest point in the cyst wall relative to the body position to aspirate the cyst fluid and to decompress the lesions (the diameter of the aspiration device was small, and the device was connected to a strong negative pressure). An echinococcosis rotary cutter was placed through the aspiration orifice to fully aspirate the cyst content. The cyst was flushed with 20% hypertonic saline, and caution was taken to prevent spillage of cyst content. The ectocyst wall was excised with an ultrasound knife, with preservation of the segment near vital blood vessels that proved challenging for removal. During laparoscopic examination, any identified points of bile leakage in the hydatid cyst wall were closed with 4-0 vascular sutures, if necessary. If leakage still existed after suturing, choledochotomy was performed for T-tube drainage. The gauze saturated with hypertonic saline was carefully placed inside a specimen pouch alongside the ectocyst wall, ensuring no contamination of the pouch exterior. A drainage tube was indwelled in the residual cavity. None of the patients required oral albendazole after intact ectocystectomy. For those receiving laparoscopic endocystectomy plus partial ectocystectomy, these patients received oral albendazole tablets at the daily dose of 10-15 mg/kg (in two equally divided doses) after normal liver function was restored. Each cycle of albendazole treatment lasted 1 month, and 3-6 cycles of treatment were delivered. Two cycles were administered, 7-10 d apart.

Patients diagnosed with asymptomatic simple hepatic cysts received no specific treatments except for follow-up observation.

Patients diagnosed with symptomatic simple hepatic cysts exceeding 5 cm and located in the liver parenchyma underwent aspiration sclerotherapy. Percutaneous liver aspiration was conducted to aspirate the fluid from the cyst, followed by injection of sclerosing agent (absolute alcohol, lauromacrogol). Laparoscopic fenestration of the hepatic cysts was performed for shallow-lying cysts with a larger volume and located no more than 1 cm from the liver capsule. The cyst fluid was aspirated using an aspiration needle under the laparoscope. After checking for the bile leakage point, sclerotherapy was administered by injecting absolute alcohol or lauromacrogol. The lesion was soaked in the sclerosing agent for several minutes before the sclerosing agent was aspirated. The cyst wall protruding outside the liver parenchyma was resected using an ultrasound knife.

Patients with CE received outpatient follow-up once every 3-6 months, and those with simple hepatic cysts received follow-up once every 6-12 months. Patients underwent abdominal ultrasound and liver function tests during the follow-up period until October 2023.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Quantitative data obeying a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD; otherwise, they were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) (25th and 75th). Pairwise comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance or the Chi-square test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 93 patients were recruited, including 30 men and 63 women aged 56.6 ± 12.3 years. All of these patients had a history of visiting CE endemic areas. In addition, 30 patients presented with distension and discomfort in the upper abdomen; 63 patients were found to have nonspecific signs and symptoms, including hepatic cysts during physical check-up.

Among the 93 patients, 21 and 72 patients were CE-positive and CE-negative, respectively.

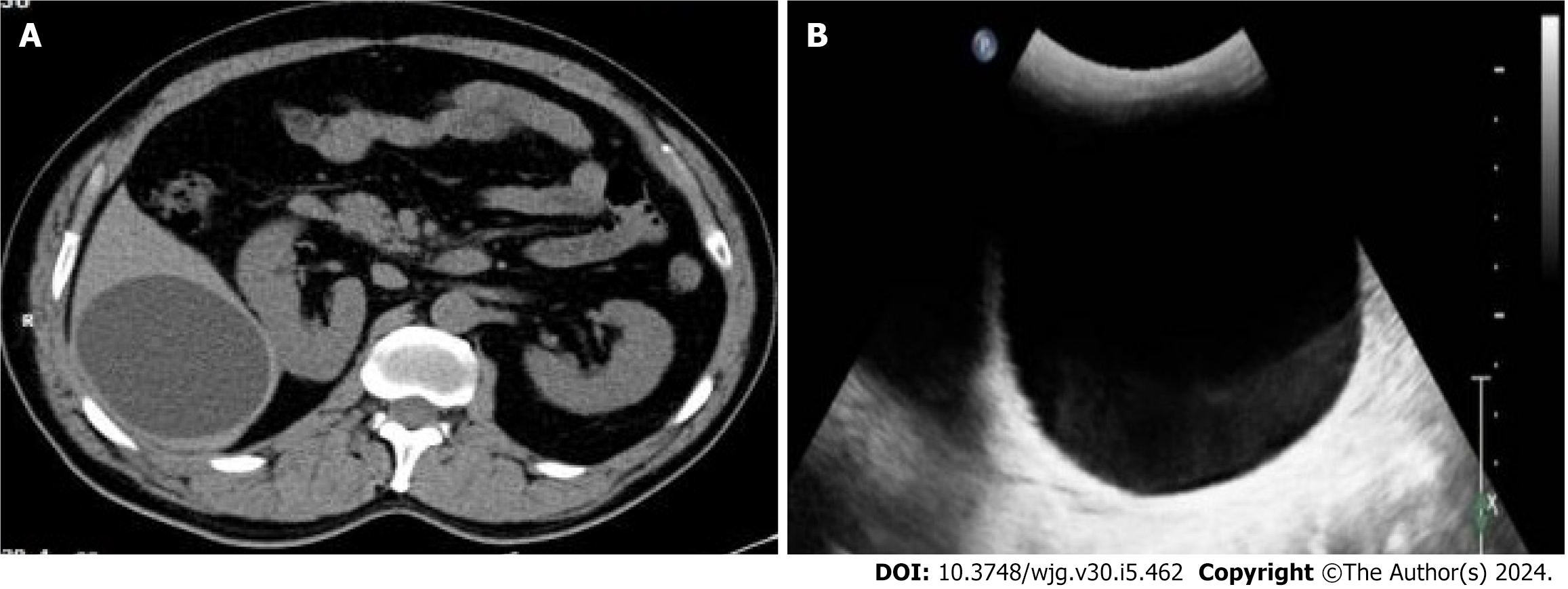

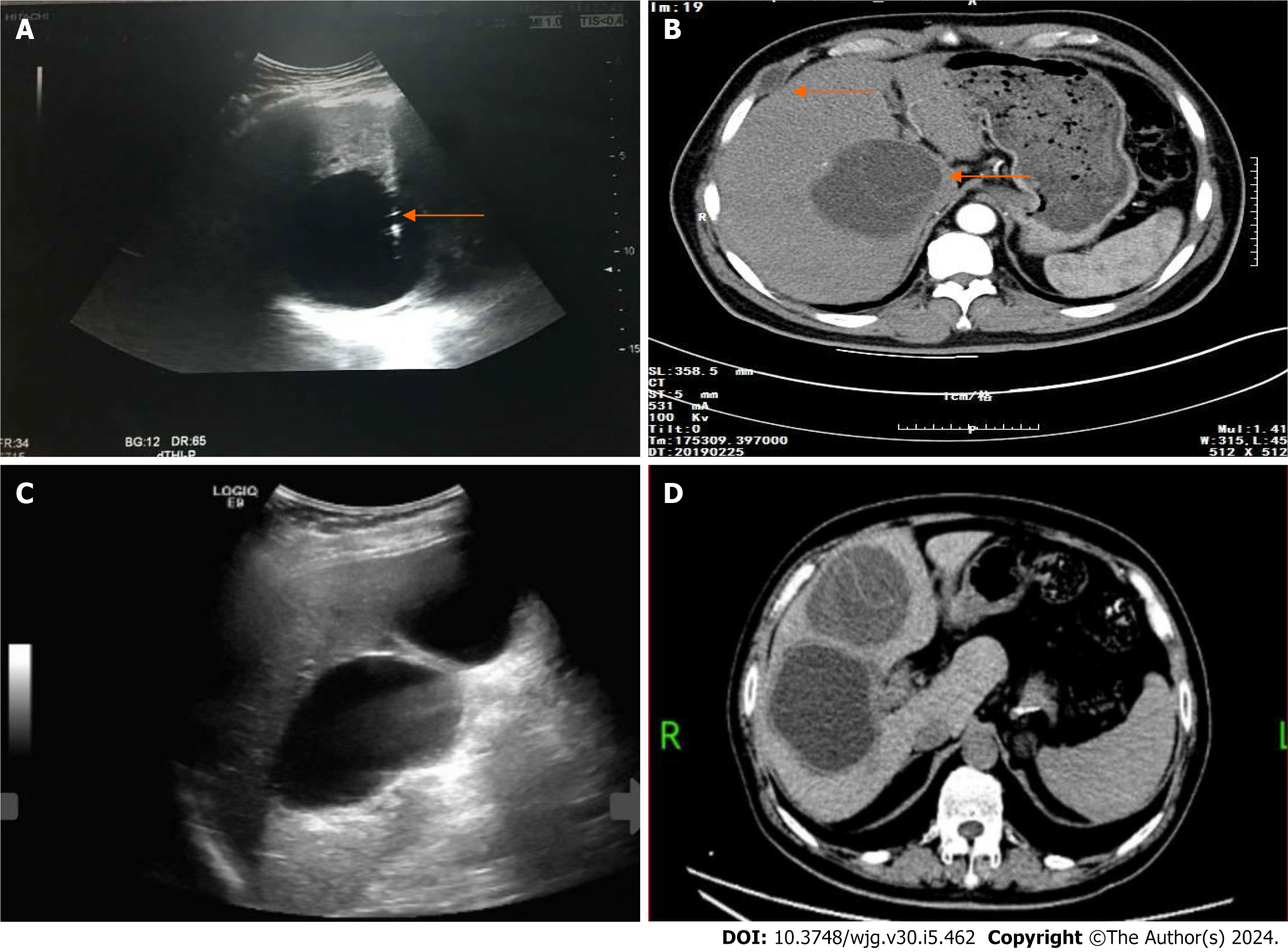

All 93 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by abdominal CT scanning (Figure 1A), with a CT value of 6.1 ± 3.4 Hounsfield Units. Notably, 79 patients had single lesions and 14 patients had multiple lesions, and the largest lesion had a diameter of 8.3 ± 3.4 cm. All 93 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by color Doppler ultrasound (convex array transducer, 3.5-5.0 MHz) (Figure 1B). Color Doppler ultrasound using a linear array transducer (5.0-12 MHz) identified the double-line sign in the top of the cystic lesion or locally thickened cyst wall in 16 patients (Figure 2). For these patients, the final diagnosis was atypical CE1. Among them, 12 patients had single lesions, and 4 patients had multiple lesions. In addition, 77 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts.

In this study, 16 patients, who were diagnosed with atypical CE1 by color Doppler ultrasound (linear array transducer, 5.0-12 MHz), underwent laparoscopy. Furthermore, 14 patients were intraoperatively diagnosed with CE1, which was consistent with the postoperative pathological diagnosis. One patient was diagnosed with a mesothelial cyst of the liver, and another patient was diagnosed with a hepatic cyst combined with local infection. Among the 14 patients who were intraoperatively diagnosed with CE1, 8 patients underwent laparoscopic endocystectomy plus partial ectocystectomy, 4 patients underwent intact laparoscopic ectocystectomy, and 2 patients underwent open endocystectomy plus intact ectocystectomy. In these 14 patients, the operation time was 3.8 ± 1.0 h, the intraoperative blood loss was 200 (IQR: 125, 350) mL, and the intraoperative blood transfusion volume was 200 (IQR: 125, 350) mL. Furthermore, 2 patients received intraoperative blood transfusion. Of these 14 patients who were intraoperatively diagnosed with CE, 3 were found to have a bile leakage point in the residual cyst wall near the first hepatic hilum after the cyst fluid was completely aspirated intraoperatively. The closure of leaks in these patients involved suturing, followed by the placement of a T-tube for drainage of the common bile duct. In the 14 patients with CE, duration of the abdominal drainage tube was 5.5 (IQR: 4.75, 8.25) d, and the hospital stay was 7.0 (IQR: 5.5, 12.0) d. Additionally, 2 patients experienced post-surgical peritoneal effusion, which was successfully treated by aspiration and drainage.

Among the 77 patients who were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts, 23 patients had abdominal distension and discomfort, as well as a hepatic cyst greater than 5 cm. Notably, 4 of these 77 patients received aspiration sclerotherapy of hepatic cysts, and 19 patients underwent laparoscopic fenestration. These patients were operatively diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts.

Notably, 14 patients with atypical CE1 received postoperative follow-up for 36.5 (IQR: 15, 50.5) months. No patients were lost to follow-up, and there were no instances of hydatid cyst recurrence or abdominal implantation.

The cohort of 77 patients, initially diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts preoperatively, included one case initially classified as atypical CE1. However, intraoperative confirmation revealed it to be a simple hepatic cyst accompanied by a local infection. The entire cohort underwent a comprehensive follow-up for 26 (IQR: 6, 44.5) months. Among the 77 patients who were preoperatively diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts, one patient later received aspiration sclerotherapy of an intrahepatic lesion (Figure 3). However, this case was diagnosed with CE2 one year after surgery during the follow-up period. There was one lesion implanted in the right intercostal space (Figure 3) and treated by open endocystectomy (Figure 4) plus partial ectocystectomy and removal of the hydatid cyst in the right intercostal space (hydatid cyst combined with bile leakage). No recurrence was found during the 55 months of postoperative follow-up. No misdiagnoses occurred in the remaining 76 patients with simple hepatic cysts during follow-up.

One patient, who was preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1, was subsequently found to have a mesothelial cyst of the liver by surgery and pathological diagnosis. No recurrence was identified during the 56 months of follow-up.

In CE endemic areas, correct diagnostic and therapeutic measures are closely associated with CE-affected patients’ health and economic benefits. Color Doppler ultrasound is the preferred option for diagnosing CE[11], and it outperforms CT and magnetic resonance imaging for CE1[12]. However, according to our clinical experience, endocysts may be invisible on abdominal color Doppler ultrasound (convex array transducer, 3.5-5.0 MHz) and abdominal spiral CT scan in some CE1 lesions. CE1 is likely to be misdiagnosed as a simple hepatic cyst, and it is therefore called "atypical CE1". Atypical lesions may be explained by the unique pathological mechanisms involved in the occurrence and development of CE. A fibrous capsule around the hydatid cyst is formed by fibroblasts, and persistent fibrous hyperplasia progresses to create a fibrous wall, identified as the ectocyst. During the early stages of ectocyst formation, fibrous hyperplasia may not be prominently expressed and may manifest as a quasi-circular hypodense lesion on multi-row spiral CT scanning. These lesions typically exhibit smooth edges and it is challenging to differentiate them from the surrounding liver parenchyma. The characteristics observed on the CT scan align with those commonly associated with simple hepatic cysts. There is mainly a lack of a well-defined cyst wall or a bilayered wall that indicates the presence of an endocyst and an ectocyst.

The present study enrolled 93 patients diagnosed with CE for the first time, each with a history of visiting endemic CE areas. All were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by spiral CT scanning and abdominal color Doppler ultrasound. Using a linear array transducer, CE1 was diagnosed in 16 cases, and 14 of them were confirmed either by surgery or follow-up observation. The diagnostic accuracy was 87.5%. One patient with a mesothelial cyst of the liver and one case of simple hepatic cyst with local infection were found to have the specific sign of the "bilayered wall" using the linear array transducer. Fortunately, the misdiagnosis in this case did not lead to adverse outcomes. Among the 77 patients who were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts using the linear array transducer, one patient receiving aspiration and drainage of the hepatic cyst was found to have CE during the follow-up period. The above results may be explained by limitations of the linear array transducer itself, although the possibility of cystic lesion (CL) could not be completely ruled out at the first diagnosis. The CL-type hydatid cyst is rare and the diagnosis is generally difficult[13]. During sonography, the diagnosis of a simple hepatic cyst is often made if there are multiple lesions (two or more). However, in the present study, among 15 patients with CE, 11 patients had single lesions and 4 had multiple lesions. Among the 77 patients diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts, 67 patients had single lesions and 10 had multiple lesions (two or more). The distribution of multiple lesions did not significantly differ between the two diseases (P = 0.177, F = 1.821). In addition, one patient was found to have two hepatic cystic lesions at first diagnosis, and both abdominal CT scanning and routine abdominal ultrasound (convex array transducer) diagnosed the lesions as simple hepatic cysts. This patient was not further examined using a linear array transducer. Two years later, the patient was admitted to hospital due to abdominal distension and pain. The diagnosis of CE Type 2 (CE2) was made, and the lesion size was enlarged, which was closely related to the right hepatic pedicle in the first hepatic hilum. This patient subsequently underwent open endocystectomy plus partial ectocystectomy, and suffered from residual cavity of hydatid cyst with bile leakage. A drainage tube was placed in the residual cavity for 40 d and a T-tube in the common bile duct for 2 months. The likelihood of misdiagnosis of CE can be reduced by the supplementary utilization of a linear array transducer during the ultrasound examination of hepatic cystic lesions, and by rectifying the empirical idea that multiple cystic lesions are generally simple hepatic cysts.

Colloidal gold-based immunochromatographic strip assay is an important method for the differential diagnosis of CE, with a sensitivity above 85% and a specificity above 85%[4]. In the present study, among 15 patients with CE, 10 (66.7%) were positive for antibodies against Echinococcus and 5 (33.3%) were negative. Among the 77 patients with simple hepatic cysts, 11 (14.3%) were positive for antibodies against Echinococcus and 66 (85.7%) were negative. The sensitivity of the colloidal gold-based immunochromatographic strip assay for detecting antibodies against Echinococcus was lower than that reported previously, while the specificity was comparable. For simple hepatic cysts causing compression, they can be treated by fenestration. Specifically, aspiration and drainage are performed at the superficial site of the liver and in the thin wall of the cyst and lower pole of the lesion, with resection of parts of the cyst wall. However, the aforementioned procedure contradicts surgical principles for CE. If a patient is misdiagnosed and receives surgery for simple hepatic cysts rather than surgery for atypical CE1, this may lead to extensive implantation of hydatid scolices in the abdomen, or even anaphylactic shock and death. In the present study, one patient was diagnosed with simple hepatic cyst upon admission and received aspiration and drainage. However, during the follow-up period, CE was confirmed in this patient and complicated with implantation of hydatid scolices in the intercostal space. It is noteworthy that this patient was negative for antibodies against Echinococcus at first diagnosis. For patients with hepatic cysts and a history of visiting endemic CE areas, CE may still be suspected even if patients are negative for antibodies against Echinococcus.

With development in laparoscopy in the field of liver surgery, this technology has demonstrated notable success in treating CE. Cugat et al[14] reviewed the data of hepatic echinococcosis treatment in 74 patients. Yagci G et al[15] retrospectively analyzed the data of 355 patients undergoing surgery for hepatic echinococcosis over a 10-year period, and they confirmed the safety and effectiveness of laparoscopy. Casulli et al[16] presented a case of cerebral CE in a child, along with a comparative molecular analysis of the isolated cyst specimens from the patient and sheep from local farms. Bakinowska et al[17] reported the surgical treatment of three different cases of pulmonary echinococcosis. They demonstrated that simple small pulmonary echinococcal lesions could be excised using endostaplers. Mfingwana et al[18] described a pediatric cohort diagnosed with pulmonary CE and treated with a combination of medical and surgical therapy. In endemic areas of hepatic echinococcosis, laparoscopy should be performed for hepatic cysts that are highly suspected to be CE, as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. In the present study, of 2 patients who were preoperatively diagnosed with CE1, laparoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of hepatic cyst in one patient and the diagnosis of a meso

The mortality of untreated CE is 2%-4%[11]. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of CE are highly important for patients’ prognosis. Differential diagnosis of atypical CE1 and simple hepatic cysts is necessary for patients with hepatic cysts who have a history of visiting endemic CE areas. A linear array transducer can facilitate the early detection of a bilayered wall or local wall thickening in cysts during color Doppler ultrasound, even before the differential sign becomes fully visible. The combined utilization of a linear array transducer, a convex array transducer, and serum immunoglobulin test for CE can enhance the diagnostic accuracy and reduce the likelihood of missed diagnoses. In cases where differentiation remains challenging using the aforementioned methods, it is recommended that patients undergo laparoscopic procedures to mitigate the potential risk of severe adverse outcomes.

Abdominal high-frequency ultrasound can detect CE1 hydatid cysts. Laparoscopy serves as an effective diagnostic and therapeutic tool for CE.

Given the distinct biological features of this disease, only a few patients with hepatic echinococcosis can receive standardized diagnosis and treatment. Some patients with cystic echinococcosis type 1 (CE1) exhibit atypical clinical manifestations, and findings from laboratory tests and radiographic examinations may not align with typical patterns. In specific cases of CE1, hydatid cysts may lack clearly defined cyst walls or characteristic endocysts. It is challenging to differentiate these lesions from simple hepatic cysts. Erroneous diagnosis and treatment of atypical CE1 may lead to grim consequences.

Developing appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for atypical CE1 hydatid cysts is of great importance.

The purpose of this study was to improve the diagnostic rate of atypical CE1. Laparoscopic procedures were performed to verify the diagnosis of atypical CE1 and to deliver a less invasive treatment, in order to reduce the misdiagnosis rate and the risks associated with potential delays in treatment.

Ninety-three patients who received treatments for simple hepatic cysts at the People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Urumqi, China) from January 2018 to September 2023 were enrolled in the study. The clinical diagnoses were made based on findings from serum immunoglobulin tests for echinococcosis, routine abdominal ultrasound, high-frequency ultrasound, abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning, and laparoscopy. Subsequent to treatments, patients with CE were followed up once every 3-6 months, and those with simple hepatic cysts once every 6-12 months. Patients underwent abdominal ultrasound and liver function tests during the follow-up period until October 2023.

Among the 93 patients, 21 and 72 patients were CE-positive and CE-negative, respectively. All 93 patients were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by conventional abdominal ultrasound and abdominal CT scanning. Among them, 16 patients were preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1, and 77 were diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts by high-frequency ultrasound. All the 16 patients preoperatively diagnosed with atypical CE1 underwent laparoscopy, of whom 14 patients were intraoperatively confirmed to have CE1, which was consistent with the postoperative pathological diagnosis, one patient was diagnosed with a mesothelial cyst of the liver, and the other was diagnosed with a hepatic cyst combined with local infection. Among the 77 patients who were preoperatively diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts, 4 received aspiration sclerotherapy of hepatic cysts, and 19 received laparoscopic fenestration. These patients were intraoperatively diagnosed with simple hepatic cysts. During the follow-up period, none of the 14 patients with CE1 experienced recurrence or implantation of hydatid scolices. One of the 77 patients was finally confirmed to have CE complicated with implantation to the right intercostal space.

Abdominal high-frequency ultrasound can detect CE1 hydatid cysts. Laparoscopy serves as an effective diagnostic and therapeutic tool for CE.

Our findings remain to be further verified by randomized clinical trials.

| 1. | Zhou S, Wan L, Shao Y, Ying C, Wang Y, Zou D, Xia W, Chen Y. Detection of aortic rupture using post-mortem computed tomography and post-mortem computed tomography angiography by cardiac puncture. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Casulli A. Recognising the substantial burden of neglected pandemics cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e470-e471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | WHO. Integrating neglected tropical diseases into global health and development: fourth WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. 2017. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255013/WHOHTM-NTD-20170·2-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. |

| 4. | Chinese Doctor Association; Chinese College of Surgeons (CCS); Chinese Committee for Hadytidology (CCH). Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis (2019 edition). Zhonghua Xiaohua Waike Zazhi. 2019;18: 71121. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | McManus DP, Gray DJ, Zhang W, Yang Y. Diagnosis, treatment, and management of echinococcosis. BMJ. 2012;344:e3866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Paternoster G, Boo G, Wang C, Minbaeva G, Usubalieva J, Raimkulov KM, Zhoroev A, Abdykerimov KK, Kronenberg PA, Müllhaupt B, Furrer R, Deplazes P, Torgerson PR. Epidemic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in Kyrgyzstan: an analysis of national surveillance data. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e603-e611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tamarozzi F, Akhan O, Cretu CM, Vutova K, Akinci D, Chipeva R, Ciftci T, Constantin CM, Fabiani M, Golemanov B, Janta D, Mihailescu P, Muhtarov M, Orsten S, Petrutescu M, Pezzotti P, Popa AC, Popa LG, Popa MI, Velev V, Siles-Lucas M, Brunetti E, Casulli A. Prevalence of abdominal cystic echinococcosis in rural Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey: a cross-sectional, ultrasound-based, population study from the HERACLES project. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:769-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dziri C, Haouet K, Fingerhut A, Zaouche A. Management of cystic echinococcosis complications and dissemination: where is the evidence? World J Surg. 2009;33:1266-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | WHO Informal Working Group. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003;85:253-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Mihmanli M, Idiz UO, Kaya C, Demir U, Bostanci O, Omeroglu S, Bozkurt E. Current status of diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:1169-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, Li J, Vuitton DA, Zhang W, McManus DP. Echinococcosis: Advances in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 100.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA; Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1638] [Cited by in RCA: 1415] [Article Influence: 88.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brunetti E, Tamarozzi F, Macpherson C, Filice C, Piontek MS, Kabaalioglu A, Dong Y, Atkinson N, Richter J, Schreiber-Dietrich D, Dietrich CF. Ultrasound and Cystic Echinococcosis. Ultrasound Int Open. 2018;4:E70-E78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cugat E, Olsina JJ, Rotellar F, Artigas V, Suárez MA, Moreno-Sanz C, Herrera J, Noguera J, Figueras J, Díaz-Luis H, Güell M, Balsells J. [Initial results of the National Registry of Laparoscopic Liver Surgery]. Cir Esp. 2005;78:152-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yagci G, Ustunsoz B, Kaymakcioglu N, Bozlar U, Gorgulu S, Simsek A, Akdeniz A, Cetiner S, Tufan T. Results of surgical, laparoscopic, and percutaneous treatment for hydatid disease of the liver: 10 years experience with 355 patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:1670-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Casulli A, Pane S, Randi F, Scaramozzino P, Carvelli A, Marras CE, Carai A, Santoro A, Santolamazza F, Tamarozzi F, Putignani L. Primary cerebral cystic echinococcosis in a child from Roman countryside: Source attribution and scoping review of cases from the literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bakinowska E, Kostopanagiotou K, Wojtyś ME, Kiełbowski K, Ptaszyński K, Gajić D, Ruszel N, Wójcik J, Grodzki T, Tomos P. Basic Operative Tactics for Pulmonary Echinococcosis in the Era of Endostaplers and Energy Devices. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mfingwana L, Goussard P, van Wyk L, Morrison J, Gie AG, Mohammed RAA, Janson JT, Wagenaar R, Ismail Z, Schubert P. Pulmonary Echinococcus in children: A descriptive study in a LMIC. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57:1173-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Eyraud D, France; Goja S, India S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S