INTRODUCTION

Benign anastomotic stricture, a late-occurring complication of colorectal cancer surgery, can result in difficulty defecating, abdominal pain, bloating, or even acute intestinal obstruction[1,2]. Although this adverse event is not life threatening, it can impact patient quality of life. The reported incidence of postoperative anastomotic strictures varies widely and is typically between 3% and 30%[3]. Endoscopic bougie and balloon dilation are first-line treatments for symptomatic anastomotic stricture[4,5], and endoscopic stricturotomy has also been proven safe and effective[6,7].

Although rare, complete colorectal anastomotic occlusion does occur[8-10], and is typically diagnosed using X-rays, computed tomography scans, or endoscopy. Further surgery is feasible but is associated with a higher postoperative morbidity rate[11]. The traditional endoscopic approaches of bougie or balloon dilation are technically difficult in cases of complete occlusion because of the inability of the guidewire to pass through the obstructed segment. Recently, a series of modified minimally invasive treatments have been successfully implemented in certain patients[12-15]. However, endoscopic treatment remains the preferred option. Herein, we report a case of anastomotic occlusion due to radial rectal resection that was successfully recanalized using a combined antegrade-retrograde endoscopic rendezvous technique (with one endoscope for radial incision and the other serving as a guide light) at the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 37-year-old man presented at the endoscopy department of our hospital in August 2023 with colorectal anastomotic occlusion diagnosed by colonoscopy three days previously.

History of present illness

The patient was diagnosed with rectal cancer at our hospital in March 2023. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the patient underwent laparoscopic low anterior rectal resection combined with prophylactic double-lumen ileostomy in June 2023. The patient recovered well without any clinical signs of anastomotic leakage or bleeding. On August 8, 2023 (three days prior to presentation), the patient returned to the hospital for ileostomy reversal, at which time preoperative colonoscopy revealed complete occlusion of the anastomosis.

History of past illness

The patient had been taking medication for hepatitis B since 2003.

Personal and family history

No significant personal or family history was reported.

Physical examination

The patient was 169 cm in height and 64.8 kg in weight, with a body mass index of 22.7 kg/m2 and recent weight loss of approximately 3 kg. His vital signs were as follows: Consciousness, clear; blood pressure, 112/83 mmHg; heart rate, 79 beats/min; body temperature, 36.5 °C; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. No abdominal distension was observed. Abdominal sounds indicated almost normal peristalsis. Scars from the laparoscopic rectal surgery were visible in the abdomen. The stoma, located in the lower right part of the abdomen, was not red or swollen. Rebound tenderness was not observed. With an undetectable anastomosis and palpable anastomotic staples, digital anal examination revealed a blind cavity at the rectal end.

Laboratory examinations

No significant abnormalities were detected in routine blood analyses, which showed the following: White blood cell count, 5.39 × 109 cells/L; red blood cell count, 4.7 × 1012 cells/L; hemoglobin level, 144 g/L; platelet count, 151 × 109 cells/L; prothrombin time, 10.8 s; activated partial thromboplastic time, 25.6 s; total bilirubin level, 13.3 μmol/L; aspartate aminotransferase level, 30.2 U/L; alanine aminotransferase level, 44.9 U/L; alkaline phosphatase level, 68.5 U/L; blood urea nitrogen level, 22.0 mg/dL; Na+/K+/Cl- levels, 144.6/3.82/104 mmol/L; and C-reactive protein level, 0.8 mg/dL.

Imaging examinations

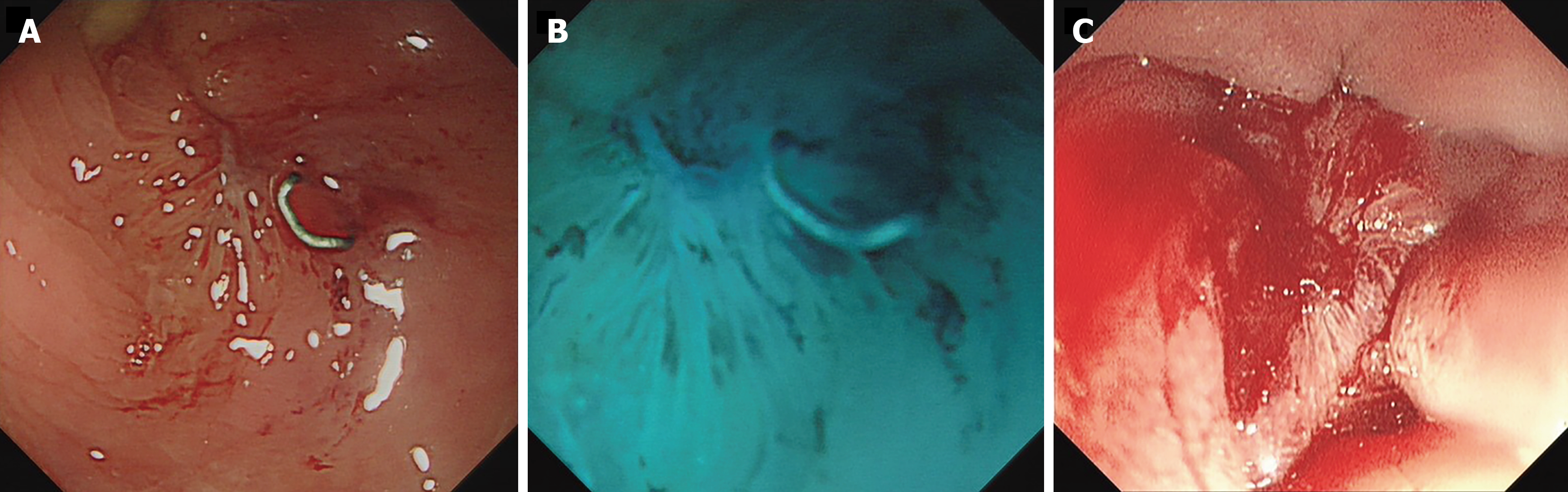

Colonoscopy revealed that the anastomosis was 3 cm from the anal verge and was completely obstructed by regenerated scar tissue (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 Complete occlusion of the colorectal anastomosis.

A: Endoscopic view from the colonic side; B: 1% methylene blue solution was used to confirm the obstruction; C: Endoscopic view from the rectal side.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

A final diagnosis of colorectal anastomotic occlusion was made based on digital anal examination and colonoscopy findings.

TREATMENT

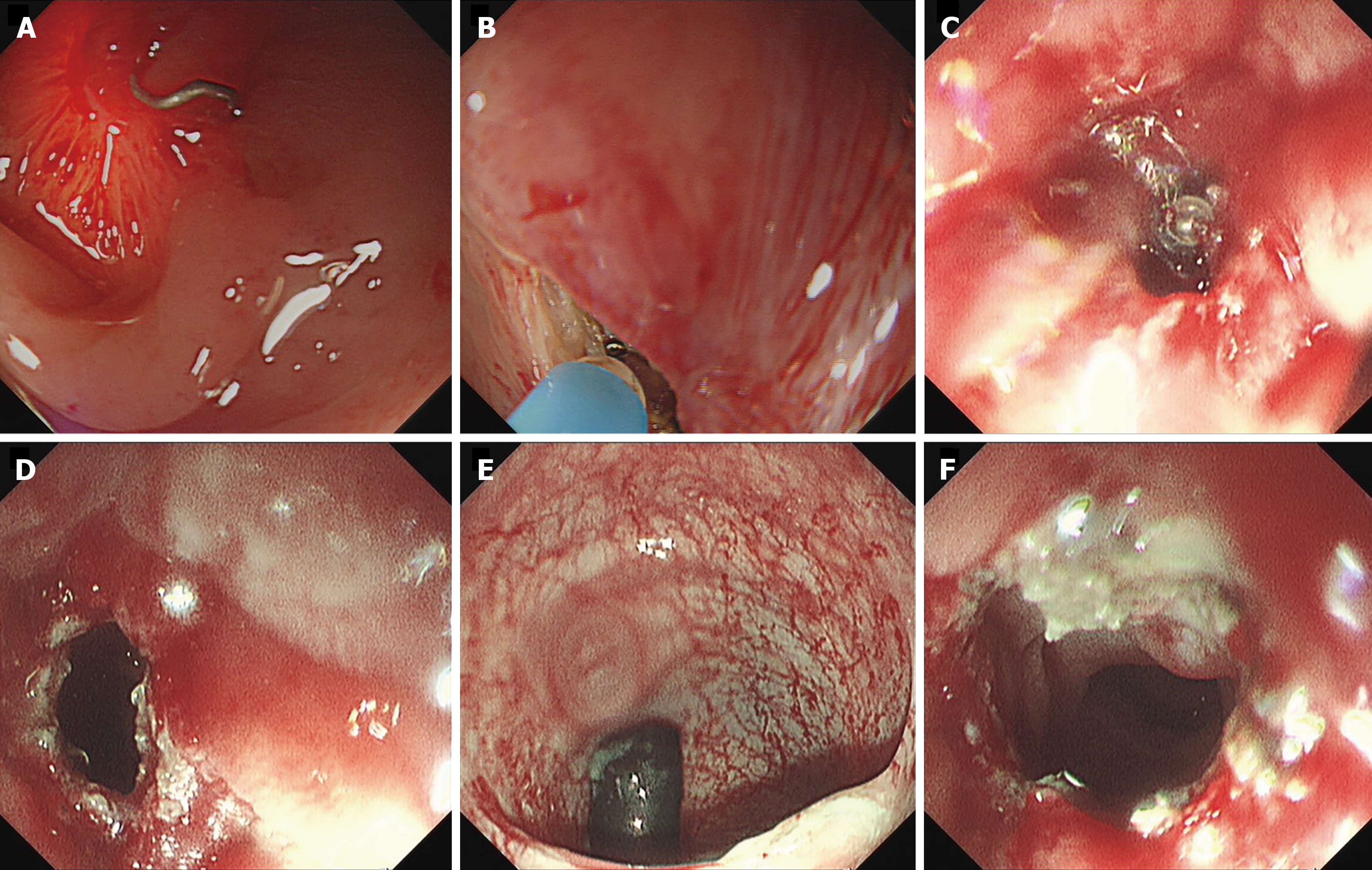

The novel atresia recanalization technique was performed on August 11, 2023. First, an antegrade endoscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced from the terminal ileum to the blind end of the anastomotic stoma, and then a retrograde endoscope (PCF-Q260AZI; Olympus Corporation) was advanced to the anastomotic occlusion through the anus. A 1% methylene blue solution injected into the lumen from the colon side did not exit through the rectum, further confirming anastomotic atresia (Figure 1B and C). The light from the retrograde endoscope easily traversed the obstructing membrane. Under transillumination, the blade of an iKnife (AMH-EK-O-2.4× 1800 (4) -N; Anrei Medical Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) was inserted precisely into the expected lumen. A small incision was successfully made from the colon side to the rectum. The incision was dilated using the antegrade endoscope until passage of the endoscopic probe was possible. The entire procedure (Figure 2 and Video) lasted less than 20 minutes, and no related adverse events (such as perforation or bleeding) were observed.

Figure 2 Details of endoscopic treatment.

A: Transillumination across the occlusive anastomosis; B: A small incision was made with an iKnife; C: Endoscopic view from the rectal side during the incision; D: Radial incision was performed successfully from the colonic side to the rectum; E: Endoscopic image showing dilation of the incision by the opposing endoscope; F: Recanalization of the occluded anastomosis.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

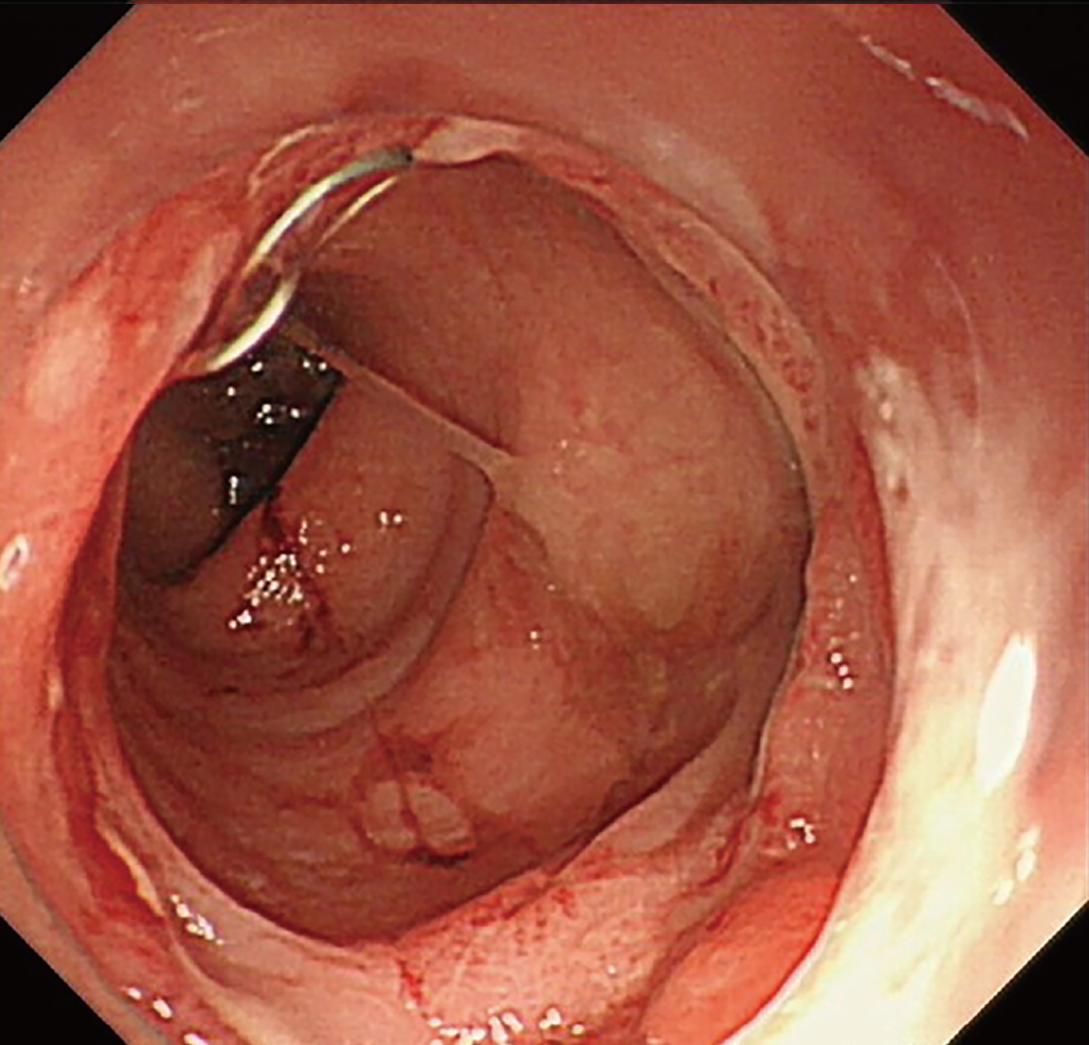

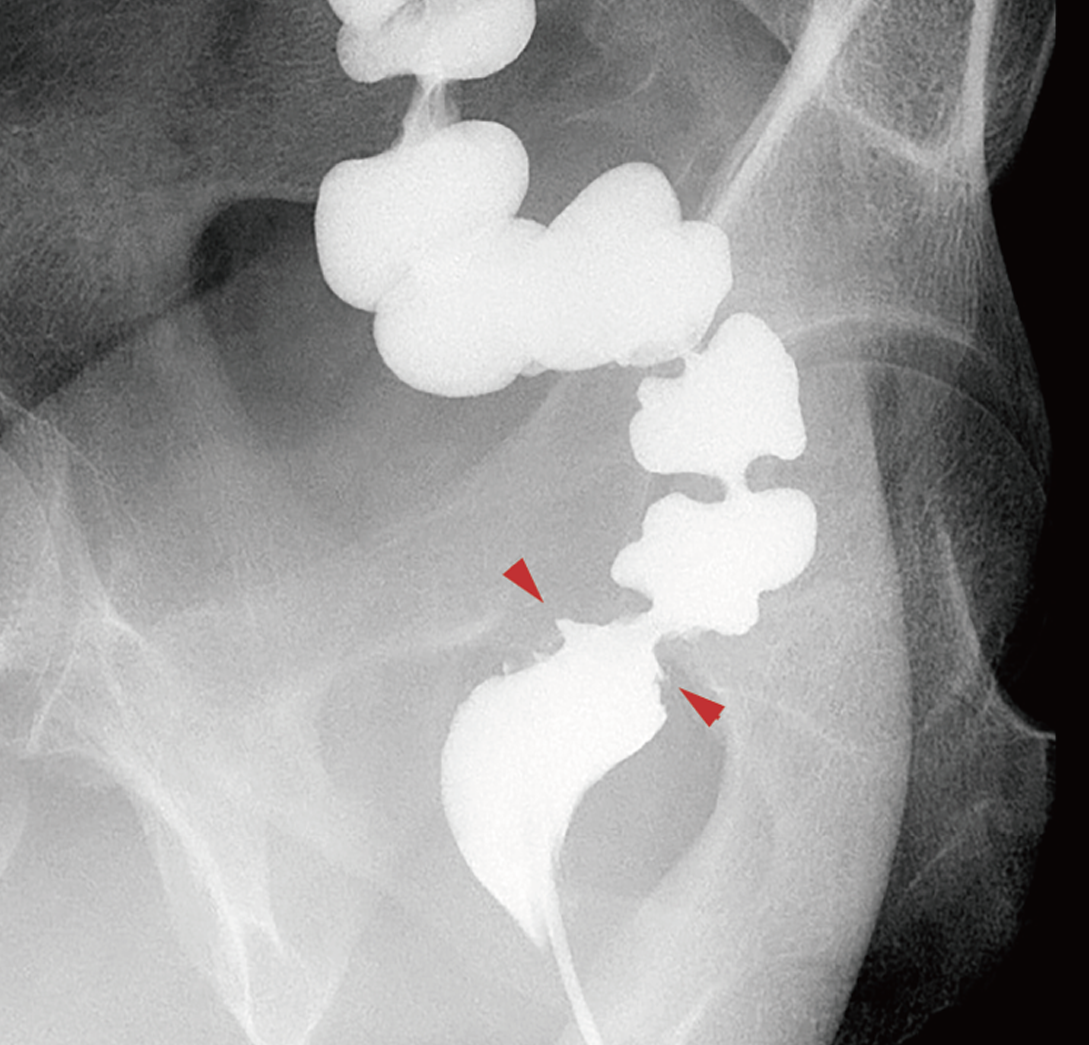

Approximately three weeks later (August 31, 2023), the patient underwent endoscopic re-examination. The obstructed colorectal anastomosis had been recanalized and was approximately 16 mm in diameter. A cap-assisted endoscope (CF-H290I; Olympus Corporation) could pass smoothly through and no anastomotic leakage was observed (Figure 3). On September 7, 2023, air and barium double-contrast radiography showed barium passing through the colorectal anastomosis with no fistula or stenosis observed (Figure 4). On September 11, 2023, the patient underwent stoma reversal. During the follow-up period, normal transanal defecation was restored. In the one year since the operation, no symptoms of anastomotic restenosis, such as abdominal pain, bloating, or difficulty defecating, have been observed. The patient continues to be followed up.

Figure 3 Endoscopy three weeks after treatment.

No anastomotic strictures or leakage were observed.

Figure 4 Air and barium double-contrast radiography.

Luminal continuity was observed to be re-established (arrows show the anastomosis).

DISCUSSION

Anastomotic stricture, a relatively common complication of colorectal cancer surgery, is defined as the inability of a rigid proctoscope to pass through the anastomosis[16]. The risk factors for this complication remain to be identified, although previous studies have associated tissue ischemia, inflammation, neoadjuvant radiotherapy, low-lying anastomotic leakage, diverting stomas, and obesity with strictures[17-21].

Various stricture management strategies are available. Asymptomatic strictures generally do not require treatment. The majority of strictures are membranous and these can be readily managed using digital dilation, endoscopic intervention, or minimally invasive transanal surgery[22,23]. Different endoscopic procedures, including bougie and balloon dilation[4,24], self-expanding metal stenting[15,25,26], and radial incision with or without dilation[14,27], have been used to treat anastomotic strictures. Sometimes, these therapies involve step-by-step procedures rather than being performed in isolation, especially in complicated cases.

Among the aforementioned techniques, the high success rate and low complication rate of endoscopic therapy make this the first choice of treatment for patients with anastomotic stricture[28]. However, conventional dilation is impossible to achieve in cases of complete anastomotic occlusion because the guidewire cannot pass through the stricture. An alternative is electrocautery incision and cutting[14]. However, occlusions obscure the position of the lumen, increasing the risk of perforation. A method of precisely identifying the location of the lumen is therefore required.

In 2006, Kaushik et al[12] reported an endoscopic rendezvous technique using two endoscopes, one advanced by an antegrade approach through the loop ileostomy and another advanced by a retrograde approach through the anus. When the two endoscopes met, a 19-gauge puncture needle was advanced through the fibrous membrane, allowing passage of a guidewire and subsequent successful balloon dilation. Similar techniques involving guidance by endoscopic ultrasound or fluoroscopy have also been proposed. Under fluoroscopic guidance, Bequis et al[10] performed rigid rectoscopy through the anus to allow puncture. A guidewire was then passed through the needle to guide balloon dilation in a retrograde manner using a flexible endoscope. Other studies[13,29,30] have reported the use of an endoscope advanced through the ileostomy to fill the colon with water or contrast dye, providing a target for endoscopic ultrasound-guided colo-colostomy with a lumen-apposing metal stent from the rectum side. As previously reported, rendezvous techniques require complicated replacement procedures performed via the endoscopic working channel, increasing surgical complexity and duration.

Herein, we describe a simpler and more feasible method for treating anastomotic occlusion that combines radial incision with an endoscopic rendezvous technique. The light from the endoscope on the opposite side of the occlusion was used to determine the exact position of the lumen. An incision was then made from the oral side towards the anal side to reduce the risk of perforation. The advantage of this procedure is that it is safe and quick, taking less than 20 minutes. As it does not require complicated instruments, the use of this procedure could also reduce the economic burden on patients.

CONCLUSION

Radial incision using the endoscopic rendezvous technique and an endoscopic probe as a guide light is a safe and effective treatment option. Compared with traditional methods, this novel technique is less invasive, enables swifter recovery, and results in a shorter hospital stay. We believe that this technique should be considered in all patients with complete colorectal anastomotic occlusion.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Gu X; Shang F S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX