Published online May 28, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i20.2726

Revised: April 14, 2024

Accepted: April 29, 2024

Published online: May 28, 2024

Processing time: 122 Days and 2.3 Hours

The screening of colorectal cancer (CRC) is pivotal for both the prevention and treatment of this disease, significantly improving early-stage tumor detection rates. This advancement not only boosts survival rates and quality of life for patients but also reduces the costs associated with treatment. However, the adoption of CRC screening methods faces numerous challenges, including the technical limitations of both noninvasive and invasive methods in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, socioeconomic factors such as regional disparities, economic conditions, and varying levels of awareness affect screening uptake. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic further intensified these cha-llenges, leading to reduced screening participation and increased waiting periods. Additionally, the growing prevalence of early-onset CRC necessitates innovative screening approaches. In response, research into new methodologies, including artificial intelligence-based systems, aims to improve the precision and accessibility of screening. Proactive measures by governments and health organizations to enhance CRC screening efforts are underway, including increased advocacy, improved service delivery, and international cooperation. The role of technological innovation and global health collaboration in advancing CRC screening is undeniable. Technologies such as artificial intelligence and gene sequencing are set to revolutionize CRC screening, making a significant impact on the fight against this disease. Given the rise in early-onset CRC, it is crucial for screening strategies to continually evolve, ensuring their effectiveness and applicability.

Core Tip: Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening holds immense significance in facilitating early detection, mitigating mortality rates, and bolstering the likelihood of favorable outcomes through less-intrusive therapeutic interventions. However, the landscape of CRC screening is fraught with diverse challenges, ranging from the intricacies of both noninvasive and invasive diagnostic modalities to socioeconomic impediments and the disruptive influence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which has noticeably attenuated screening frequencies. The emergence of early-onset CRC further compounds these challenges, necessitating tailored screening approaches. In the future, advancements in artificial intelligence and gene sequencing technologies harbor the promise of profoundly transforming CRC screening paradigms, potentially increasing their efficacy and accessibility. Forging global health collaborations will be pivotal in propelling the future of CRC prevention and treatment.

- Citation: Li J, Li ZP, Ruan WJ, Wang W. Colorectal cancer screening: The value of early detection and modern challenges. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(20): 2726-2730

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i20/2726.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i20.2726

Our interest was deeply piqued by the study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology. This study explored the multifaceted challenges confronting contemporary colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. These challenges span from intricate technical hurdles and disruptions in screening protocols due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to the increasing prevalence of early-onset CRC. While the study is rich in knowledge and perceptive observations, there are certain constraints on its research design and breadth, paving the way for more extensive deliberations.

This piece serves as a thoughtful response to that exemplary study. Tonini and Zanni[1] present a thorough survey of present-day CRC screening practices and the obstacles they face in real-world applications. We express our utmost gratitude for the authors' meticulous articulation of the myriad factors impeding effective CRC screening. Nevertheless, we posit that there are still facets worthy of further exploration. By delving into these aspects, we can potentially elevate the discourse on CRC screening to a more profound and exhaustive level.

CRC screening represents a pivotal preventative and diagnostic tool in the fight against this debilitating disease. Through the utilization of CRC screening, malignancies can be identified in their nascent stages, preceding any widespread metastasis and often before the emergence of overt symptoms[2,3]. This early intervention significantly bolsters the prospect of a favorable prognosis[4,5]. Early detection not only paves the way for simpler, less intrusive therapeutic modalities, thus mitigating the rigors and potential side effects of treatment but also notably enhances survival rates and preserves the overall quality of life for affected individuals[6,7].

Moreover, the implementation of CRC screening has considerable economic implications[8,9]. It serves to mitigate the financial and emotional toll inflicted upon patients, their families, and society at large by reducing the overall cost of treatment. For those already diagnosed, CRC screening serves as a vital tool for monitoring disease progression and assessing the efficacy of ongoing treatment, enabling clinicians to make timely adjustments to therapeutic strategies.

Hence, active engagement in CRC screening is not simply a prudent health measure for individuals to undertake for their own well-being; it is also an indispensable strategy in the prevention of CRC and the optimization of survival outcomes and quality of life[9].

Nevertheless, despite the unequivocal importance of CRC screening, its practical implementation remains fraught with numerous challenges. Chief among these is the array of technical obstacles that continue to impede its widespread adoption and effective utilization[10,11].

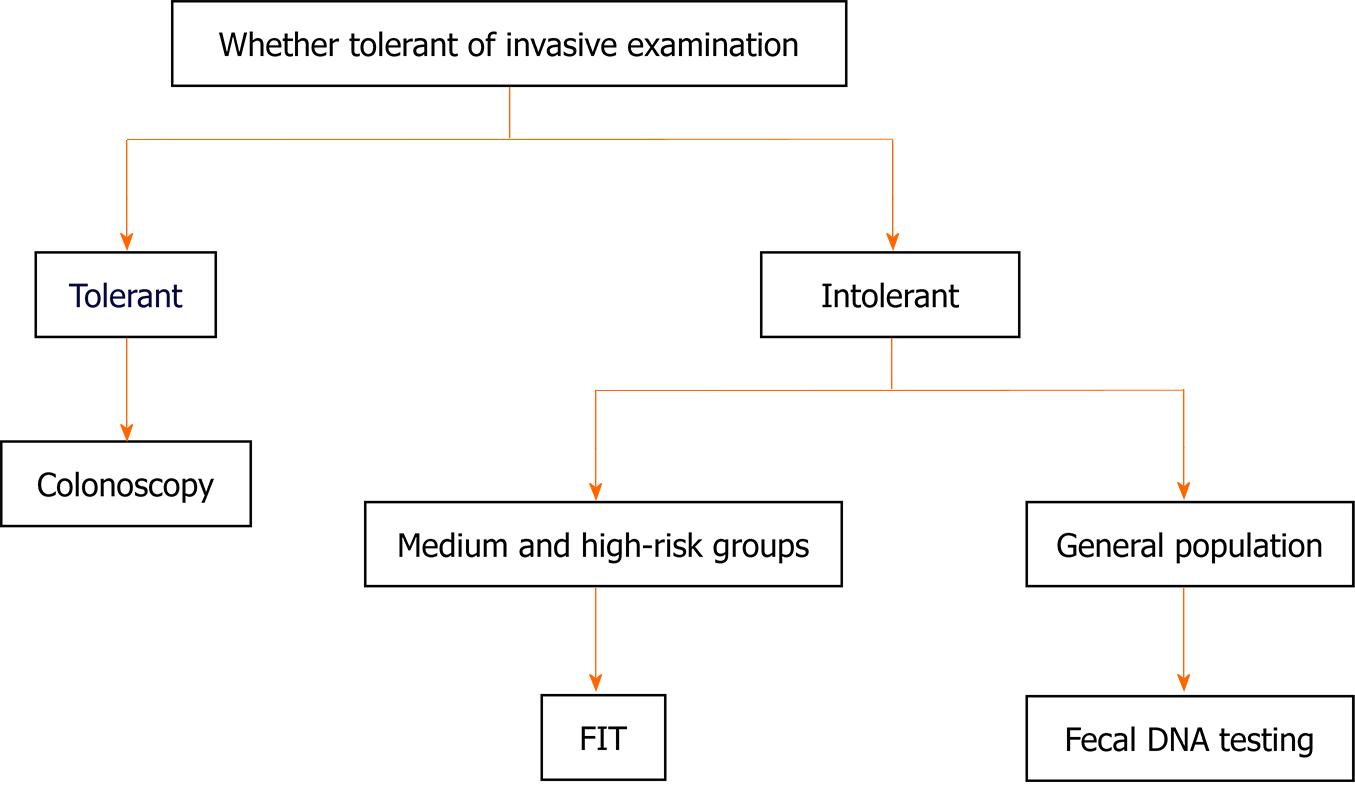

CRC screening techniques are primarily divided into two distinct categories: Noninvasive and invasive procedures[12]. Noninvasive screenings, such as fecal occult blood tests and stool DNA analyses, are valued for being straightforward and nonintrusive. However, their limited sensitivity and specificity can lead to misdiagnoses or undetected conditions (Table 1 and Figure 1).

| Screening technology | Examination items | Advantage | Disadvantage | Applicable group |

| Non-invasive | FIT | Simple, noninvasive, and can be done at home | The sensitivity to early-stage lesions is relatively low, which may lead to false-negative results | Applicable to high-risk groups and some moderate-risk groups, such as those with family history, intestinal inflammatory diseases, etc. |

| Fecal DNA testing | It can detect genetic variations related to colorectal cancer with high sensitivity and specificity | The high cost may limit its application in large-scale screening | Preliminary screening for the general population | |

| Invasive | Colonoscopy | It can detect early precancerous lesions and early-stage cancers with high accuracy, serving as the gold standard for CRC diagnosis | It may cause discomfort. The examination is expensive and requires professional doctors to perform | Applicable for screening of the general population, especially for patients who have concerns about colonoscopy |

In contrast, invasive tests-predominantly colonoscopies-offer direct visual inspection of the intestinal tract, facilitating the biopsy of potential lesions. These procedures are highly regarded for their accuracy and reliability, establishing them as the gold standard in CRC screening. Nevertheless, these patients require sophisticated medical infrastructure and skilled personnel, often leading to decreased patient compliance due to their more involved nature.

To address the technical complexities associated with CRC screening, researchers are actively pursuing innovative screening approaches and technologies. One such example is the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven CRC screening systems[13-15]. These systems leverage the power of AI to analyze biological markers present in stool samples, enabling the prediction of an individual's CRC risk. This cutting-edge technology promises efficiency, precision, and scalability, heralding potential breakthroughs in CRC screening practices[16].

In addition to technical obstacles, CRC screening is associated with significant socioeconomic hurdles. First, there are notable disparities in CRC screening prevalence across various regions and demographic groups[9]. While some developed regions have successfully integrated CRC screening into their public health systems, achieving high participation, underdeveloped areas struggle with scarce healthcare resources and lack awareness, resulting in lower screening uptake.

Second, the financial burden of CRC screening has emerged as a pivotal determinant of patient uptake. In some countries, the cost of CRC screening can be prohibitively high, rendering it inaccessible to economically vulnerable individuals who may forgo screening due to financial constraints. Hence, reducing the financial burden of CRC screening and enhancing its accessibility are crucial imperatives in the current CRC screening landscape.

To address these socioeconomic challenges, governments and healthcare institutions are implementing a range of strategies. For instance, they are intensifying awareness campaigns to educate the public about the importance of CRC screening, formulating targeted policies to encourage high-risk groups to undergo screening, and forging stronger collaborations with international bodies and medical institutions to jointly advance the dissemination and progress of CRC screening.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted global health systems in recent years, severely affecting CRC screening initiatives. Because of the stringent measures implemented during the crisis and widespread patient apprehension, among other factors, participation rates in CRC screening have plummeted significantly. Moreover, the pandemic has placed a tremendous burden on medical resources, leading to extended wait times for screenings and further exacerbating the already considerable burden on patients[17,18].

To mitigate the effects of the pandemic on CRC screening, governments and healthcare institutions are taking proactive and decisive action. They are actively promoting innovative service models, such as remote screening and virtual consultations, aimed at minimizing the risk of infection for patients seeking medical attention. Additionally, they are prioritizing the optimization of screening processes and operational efficiency to reduce wait times for patients. Furthermore, significant efforts are being made to enhance communication and provide clear explanations to patients, alleviating their fears and addressing their concerns effectively.

The incidence of early-onset CRC, defined as cases diagnosed before age 50[19], has alarmingly risen in recent years, challenging the adequacy of current screening strategies, which are traditionally focused on high-risk individuals aged 50 and older, often overlooking those affected by early-onset CRC. As such, the urgent need to adapt and refine screening strategies to account for this shift in demographics has become a pivotal issue.

To address the unique challenges presented by early-onset CRC, researchers are actively pursuing innovative screening strategies and approaches. These researchers are engaging in rigorous research and analysis to identify high-risk factors specifically associated with early-onset CRC, aiming to develop more refined and targeted risk assessment models. Furthermore, there is ongoing deliberation regarding the appropriate lowering of the screening age threshold to ensure the timely detection of a broader range of early CRC patients. Additionally, considerable emphasis is being placed on enhancing public awareness and education regarding early-onset CRC, with the goal of increasing knowledge and fostering a greater sense of urgency toward this growing health concern.

In summary, CRC screening has achieved notable progress despite encountering a multitude of challenges. Through relentless exploration, innovation in screening technologies and methodologies, intensified promotional endeavors, streamlining of service processes, and other strategic measures, we can systematically address the obstacles confronting CRC screening and offer more impactful screening strategies alongside comprehensive health security for those affected by CRC.

Future prospects for CRC screening are promising, with technological advancements and improved medical practices poised to drive significant transformations. Cutting-edge technologies, such as AI and gene sequencing, are destined to play a pivotal role in revolutionizing CRC screening. Concurrently, as global health cooperation continues to flourish and intensify, the prevalence of CRC screening is anticipated to increase, thereby making a more significant and far-reaching contribution to CRC prevention and treatment efforts worldwide.

| 1. | Tonini V, Zanni M. Why is early detection of colon cancer still not possible in 2023? World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Boyaval F, Dalebout H, Van Zeijl R, Wang W, Fariña-Sarasqueta A, Lageveen-Kammeijer GSM, Boonstra JJ, McDonnell LA, Wuhrer M, Morreau H, Heijs B. High-Mannose N-Glycans as Malignant Progression Markers in Early-Stage Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van de Veerdonk W, Hoeck S, Peeters M, Van Hal G, Francart J, De Brabander I. Occurrence and characteristics of faecal immunochemical screen-detected cancers vs non-screen-detected cancers: Results from a Flemish colorectal cancer screening programme. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Arnold CL, Rademaker AW, Morris JD, Ferguson LA, Wiltz G, Davis TC. Follow-up approaches to a health literacy intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening in rural community clinics: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2019;125:3615-3622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta A, Saini SD, Naylor KB. Increased Driving Distance to Screening Colonoscopy Negatively Affects Bowel Preparation Quality: an Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:1666-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sun Z, Ji S, Wu J, Tian J, Quan W, Shang A, Ji P, Xiao W, Liu D, Wang X, Li D. Proteomics-Based Identification of Candidate Exosomal Glycoprotein Biomarkers and Their Value for Diagnosing Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:725211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mariappan L, Shao Q, Jiang C, Yu K, Ashkenazi S, Bischof JC, He B. Magneto acoustic tomography with short pulsed magnetic field for in-vivo imaging of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:689-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramos MC, Passone JAL, Lopes ACF, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ribeiro Júnior U, de Soárez PC. Economic evaluations of colorectal cancer screening: A systematic review and quality assessment. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2023;78:100203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cruzado J, Sánchez FI, Abellán JM, Pérez-Riquelme F, Carballo F. Economic evaluation of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:867-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jayasinghe M, Prathiraja O, Caldera D, Jena R, Coffie-Pierre JA, Silva MS, Siddiqui OS. Colon Cancer Screening Methods: 2023 Update. Cureus. 2023;15:e37509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brenner H, Chen C. The colorectal cancer epidemic: challenges and opportunities for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu X, Zhang Y, Hu T, He X, Zou Y, Deng Q, Ke J, Lian L, Zhao D, Cai X, Chen Z, Wu X, Fan JB, Gao F, Lan P. A novel cell-free DNA methylation-based model improves the early detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:2702-2714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mitsala A, Tsalikidis C, Pitiakoudis M, Simopoulos C, Tsaroucha AK. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment. A New Era. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:1581-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rompianesi G, Pegoraro F, Ceresa CD, Montalti R, Troisi RI. Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:108-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Wallace MB, Sharma P, Bhandari P, East J, Antonelli G, Lorenzetti R, Vieth M, Speranza I, Spadaccini M, Desai M, Lukens FJ, Babameto G, Batista D, Singh D, Palmer W, Ramirez F, Palmer R, Lunsford T, Ruff K, Bird-Liebermann E, Ciofoaia V, Arndtz S, Cangemi D, Puddick K, Derfus G, Johal AS, Barawi M, Longo L, Moro L, Repici A, Hassan C. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Miss Rate of Colorectal Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:295-304.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Koohi-Moghadam M, Borad MJ, Tran NL, Swanson KR; Boardman LA; Sun H, Wang J. MetaMarker: a pipeline for de novo discovery of novel metagenomic biomarkers. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:3812-3814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Randle HJ, Gorin A, Manem N, Feustel PJ, Antonikowski A, Tadros M. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;80:102212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kopel J, Ristic B, Brower GL, Goyal H. Global Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening: Current Insights and Future Directions. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stanich PP, Pelstring KR, Hampel H, Pearlman R. A High Percentage of Early-age Onset Colorectal Cancer Is Potentially Preventable. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1850-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/