Published online Sep 7, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i33.4823

Peer-review started: January 28, 2022

First decision: March 11, 2022

Revised: March 17, 2022

Accepted: August 14, 2022

Article in press: August 14, 2022

Published online: September 7, 2022

Processing time: 214 Days and 14.3 Hours

Biologic therapy resulted in a significant positive impact on the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) however data on the efficacy and side effects of these therapies in the elderly is scant.

To evaluate retrospectively the drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety of the biologic therapies in the elderly IBD population.

Consecutive elderly (≥ 60 years old) IBD patients, treated with biologics [inflixi

We identified a total of 147 elderly patients with IBD treated with biologicals during the study period, including 109 with Crohn’s disease and 38 with ulcerative colitis. Patients received the following biologicals: IFX (28.5%), ADAL (38.7%), VDZ (15.6%), UST (17%). The mean duration of biologic treatment was 157.5 (SD = 148) wk. Parallel steroid therapy was given in 34% at baseline, 19% at 3 mo, 16.3% at 6-9 mo and 6.5% at 12-18 mo. The remission rates at 3, 6-9 and 12-18 mo were not significantly different among biological therapies. Kaplan-Meyer analysis did not show statistical difference for drug sustainability (P = 0.195), time to adverse event (P = 0.158) or infection rates (P = 0.973) between the four biologics studied. The most common AEs that led to drug discontinuation were loss of response, infusion/injection reaction and infection.

Current biologics were not different regarding drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety in the elderly IBD population. Therefore, we are not able to suggest a preferred sequencing order among biologicals.

Core Tip: Data on the efficacy and side effects of biologic therapies in the elderly inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population is scant. Our single center study evaluates retrospectively the drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety of approved biologic therapies in this sensitive population. The major finding of our study was that the drug sustainability and safety of the different biologicals were not significantly different in a large real-world, elderly IBD cohort treated in this single tertiary IBD center. As a consequence, we are still not able to suggest a preferred sequencing order among biologicals.

- Citation: Hahn GD, LeBlanc JF, Golovics PA, Wetwittayakhlang P, Qatomah A, Wang A, Boodaghians L, Liu Chen Kiow J, Al Ali M, Wild G, Afif W, Bitton A, Lakatos PL, Bessissow T. Effectiveness, safety, and drug sustainability of biologics in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(33): 4823-4833

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i33/4823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i33.4823

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic immune-mediated diseases classified as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which can result in progressive bowel damage and disability. Although more common in young adults, the prevalence and the incidence of IBD are increasing in the elderly[1]. Approximately 10%-15% of new IBD diagnoses occur in individuals over 60 years (elderly-onset IBD), while the majority of older patients with IBD are classified as adult-onset IBD, meaning they were diagnosed with IBD between 18-59 years old[2-4]. There has been a revolution in the medical therapy of IBD with the advent of biological agents in the past two decades leading to improved clinical outcomes. Biological therapies were also associated with adverse events (AEs), including infusion/ injection reactions, infections, and malignancies. Elderly IBD patients are in many ways a difficult-to-treat patient population, and may be even more vulnerable to AEs due to advanced age, comorbidities and polypharmacy[5].

The proportion of elderly IBD patients in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) is usually small, therefore there is lack of data concerning effectiveness and safety profiles of biologic therapies in this population. This relative paucity of data together with the higher frequency of comorbidities, polypharmacy, and the perceived toxicity of IBD drug therapies in the elderly patients may likely explain the underuse of biological agents and the reported higher rates of steroid use. As reported by studies from France, Sweden and Hong Kong, only 1%-3% of elderly IBD patients received biologic therapy within five to ten years of follow-up[6-8].

The expected rate of AE and medication interactions may significantly influence the choice of therapy in the elderly IBD population. In a study from Leuven, advanced age was associated with higher rates of serious AEs (SAEs) on anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy, such as infections and malignancy[9]. In contrast, recent data from pooled analyses of RCTs suggest that the advanced age, and not anti-TNF exposure, was associated with increased rates of SAE and hospitalizations[10].

Furthermore, landmark trials evaluating the more recently approved biologic agents, such as vedolizumab (VDZ) or ustekinumab (UST), suggested a more beneficial overall safety profile[11,12]. However, the existing literature is limited regarding effectiveness and safety of these agents in the elderly population. A post hoc analysis of the GEMINI trials reported that in IBD patients above 55 years old the efficacy and safety of VDZ was similar to younger IBD patients, while the safety profile was not different from placebo[13]. Relatively few data are available in elderly IBD patients on the efficacy or safety on anti-TNFs and on the new biologicals. One of the first studies in elderly patients was Busquets et al[14] which performed a systematic review on efficacy and safety of anti-TNFs in the elderly, however mainly in patients with rheumatic diseases. It concluded that elderly patients on anti-TNF therapy have higher number of AEs, and similar efficacy, when compared with younger patients. The aim of our study was to measure the rates of biologic therapy sustainability in elderly IBD patients, as well as to report their effectiveness and safety profile.

Consecutive elderly patients (aged 60 years or over) previously or currently treated with a biologic agent and followed at the McGill University Health Centre Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Center between January 2000 and January 2020 were included retrospectively. The efficacy of treatment with a biologic agent was assessed by clinical score, biochemical and endoscopy. Clinical response and remission using the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) and Mayo score were measured at baseline, 3 mo, 6-9 mo, and 12-18 mo of follow up. Patients included were patients with IBD, with an age of 60 years or older, whose current or prior treatment included biological agents (anti-TNF, VDZ or UST). Patients with contra-indications to biologic therapy, or patients with less than 3 mo follow-up were excluded. For patients with multiple biological exposure, data for the last biological therapy was collected.

Local electronic medical charts were used to identify elderly IBD patients on infliximab (IFX), adalimumab (ADAL), VDZ or UST. We collected demographic data (age, gender), comorbidities, age at diagnosis, disease duration, disease extent and phenotype (Montreal classification)[15], prior gastrointestinal surgeries, C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, radiological or endoscopic reports and clinical symptoms of IBD activity. Additional therapeutic variables measured were treatment duration and dosage, prior or concomitant immunosuppression, parallel steroid therapy. Comorbidity was measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), where a CCI of 0 represents absence of comor

The primary outcome was the drug sustainability and comparative time-dependent safety analysis in elderly patients with IBD (aged 60 years or over) on different biologic therapy. Secondary outcomes included the comparison of rates of clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic remission in elderly IBD patients according to the biologic therapy used. Clinical response was defined as a decrease in the HBI by 3 points or more from baseline for CD or a similar decrease in the partial Mayo Score (pMayo) by 3 or more for UC, while clinical remission was defined as an overall HBI of less than 5 for CD or an overall pMayo of less than 2 for UC[17].

AE or SAE occurring within three months of the last biologic dose were considered to be related to the biologic agent. SAEs were defined as potentially life-threatening or leading to death, hospitalization, or prolongation of hospitalization, or causing significant disruption in normal life functions. Infections and malignancy were separately captured. Reasons for discontinuation of the biologic agent were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 20.0; SPSS INC., Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and treatment-related characteristics along with means ± SD, and common themes highlighted using qualitative data analysis. Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables while the Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Kaplan Meier curves were plotted with COX regression analysis to assess differences in drug sustainability, infections or AE stratified by the different biological agents. A P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

This study was reviewed and approved by the McGill University Health Centre Research Ethics Board under the ethical approval number: 2019-5209. The research protocol conforms to ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (6th revision, 2008) and local regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

A total of 147 elderly patients with IBD were identified, including 109 patients with CD and 38 patients with UC. The majority of patients (75.5%) were diagnosed before the age of 60, thus adult-onset, elderly IBD patients. Disease location was predominantly ileocolonic (47.7%) in patients with CD and pancolitis for patients with UC (63.2%). Among patients with CD, 21.1% suffered from perianal disease. The CCI was at least 1 in 95.2% of elderly IBD patients, at least 3 in 47.6% and above 4 in 12.9%. Approximately 45.6% (67 patients) of all included patients underwent at least one surgical resection related to IBD. 70 elderly IBD patients (47.6%) had previous exposure to other biologics. Over the study period, 35.4% of patients had received a course of systemic steroids at least once, while 17% were treated with concomitant immunomodulatory therapy. The mean duration of biological therapy was 157.5 (SD = 148) wk. Extraintestinal manifestations had been diagnosed in 10.9% of elderly IBD patients. Table 1 summarizes disease characteristics and history of IBD-related therapy.

| Biological therapy | |||||

| Vedolizumab % (n = 23) | Adalimumab % (n = 57) | Infliximab % (n = 42) | Ustekinumab % (n = 25) | ||

| Age at IBD diagnosis (yr) | < 60 | 69 (16) | 81 (46) | 71 (30) | 76 (19) |

| ≥ 60 | 30 (7) | 19 (11) | 28 12 | 24 (6) | |

| IBD type | CD | 52 (12) | 81 (46) | 64 (27) | 96 (24) |

| UC | 48 (11) | 19 (11) | 36 (15) | 4 (1) | |

| CD location | Ileal (L1) | 17 (4) | 24 (14) | 9 (4) | 12 (3) |

| Colonic (L2) | 4 (1) | 21 (12) | 19 (8) | 24 (6) | |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 26 (6) | 31 (18) | 38 (16) | 48 (12) | |

| Isolated upper GI disease (L4) | 4 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Combined upper GI disease with L1, 2 or 3 | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 12 (3) | |

| Disease behavior | Luminal (B1) | 17 (4) | 38 (22) | 24 (10) | 32 (8) |

| Stricturing (B2) | 26 (6) | 28 (16) | 28 (12) | 44 (11) | |

| Penetrating (B3) | 13 (3) | 16 (9) | 17 (7) | 24 (6) | |

| CD perianal | Presence of perianal disease | 9 (2) | 12 (7) | 24 (10) | 16 (4) |

| UC extension | Proctitis (E1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Left-sided (E2) | 26 (6) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 0 | |

| Pancolitis (E2) | 22 (5) | 12 (7) | 26 (11) | 4 (1) | |

| UC severity (Mayo score) | 1 | 13 (3) | 9 (5) | 5 (2) | 0 |

| 2 | 17 (4) | 7 (4) | 17 (7) | 0 | |

| 3 | 17 (4) | 3 (2) | 9 (4) | 4 (1) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0 | 0 | 9 (5) | 5 (2) | 0 |

| 1-2 | 56 (13) | 54 (31) | 38 (16) | 36 (9) | |

| 3-4 | 26 (6) | 28 (16) | 48 (20) | 36 (9) | |

| More than 4 | 17 (4) | 9 (5) | 7 (3) | 28 (7) | |

| History of malignancy | Active within last 5 yr | 4 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Active more than 5 yr prior | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 0 | |

| Prior resective surgery | Surgical resection ≥ 1 | 43 (10) | 44 (25) | 33 (14) | 72 (18) |

| Previous exposure to biologics | Bio-naïve | 39 (9) | 54 (31) | 76 (32) | 20 (5) |

| Previous exposure to anti-TNF | 61 (14) | 46 (26) | 21 (9) | 80 (20) | |

| Previous exposure to VDZ | 0 | 0 | 7 (3) | 4 (1) | |

| Previous exposure to UST | 9 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Concomitancy of 5-ASA | Yes | 39 (9) | 14 (8) | 8 (19) | 16 (4) |

| Concomitancy of systemic steroids at baseline | Yes | 43 (10) | 26 (15) | 40 (17) | 40 (10) |

| Concomitancy of immunomodulator at baseline | Yes | 9 (2) | 17 (10) | 26 (11) | 8 (2) |

| History of an extraintestinal manifestation | Musculoskeletal | 0 | 3 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Ocular | 0 | 3 (2) | 5 (2) | 8 (2) | |

| Mucocutaneous | 4 (1) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | 12 (3) | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1) | |

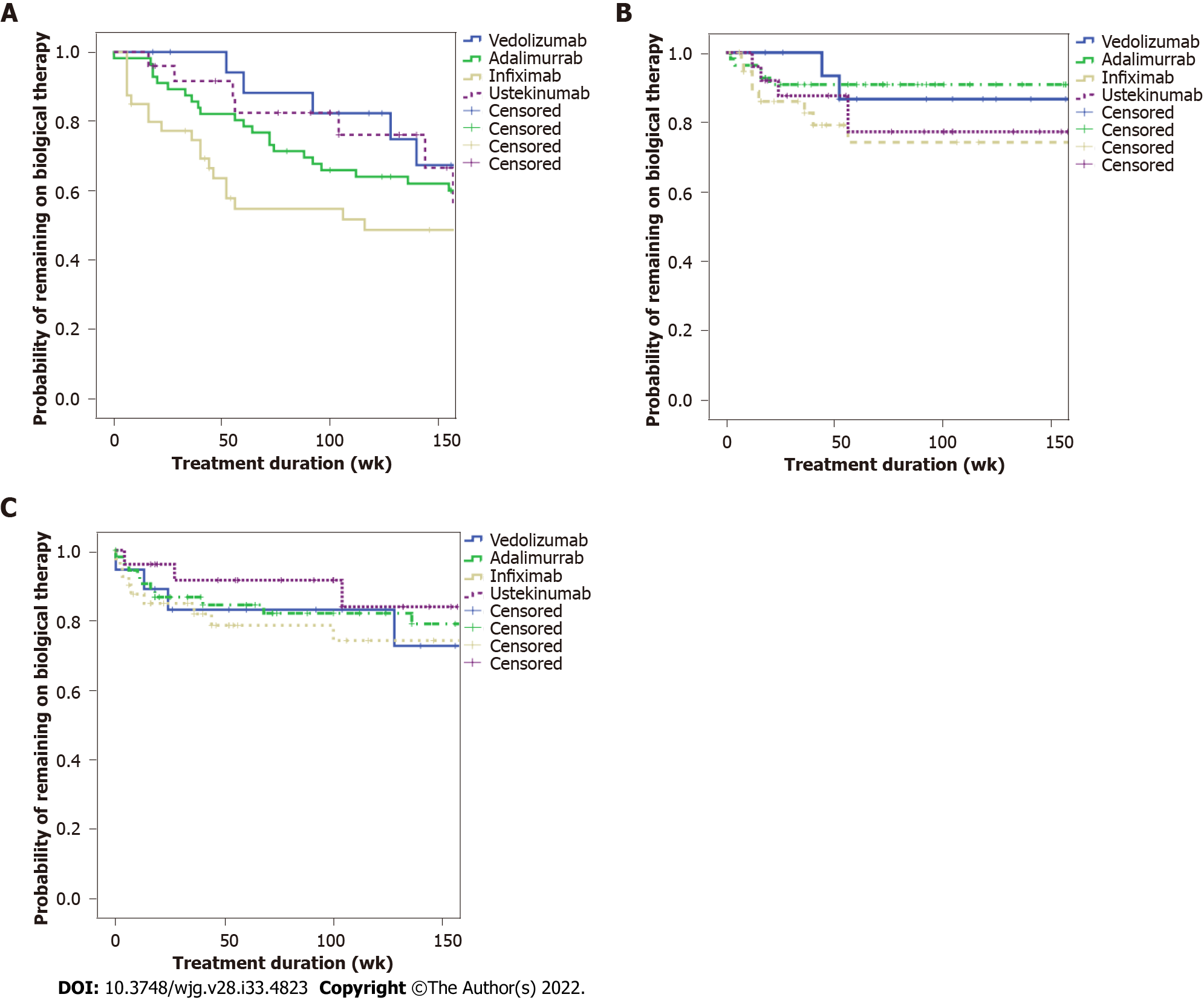

Figure 1A (see appendix section) shows the time to treatment discontinuation stratified by the biological agent by Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analysis. No significant difference was found among the four biologicals (P = 0.195) (Figure 1A). According to Figure 1B, the time to AE was not significantly different in a Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analysis among the four biologics (P = 0.158). Figure 1C shows the time to infections stratified by the biological agent. There was no statistical difference among the biologicals among the respective time to infection curves (P = 0.973). SAE was observed in only one patient (0.6%), who presented fever of unknown origin, needing hospitalization.

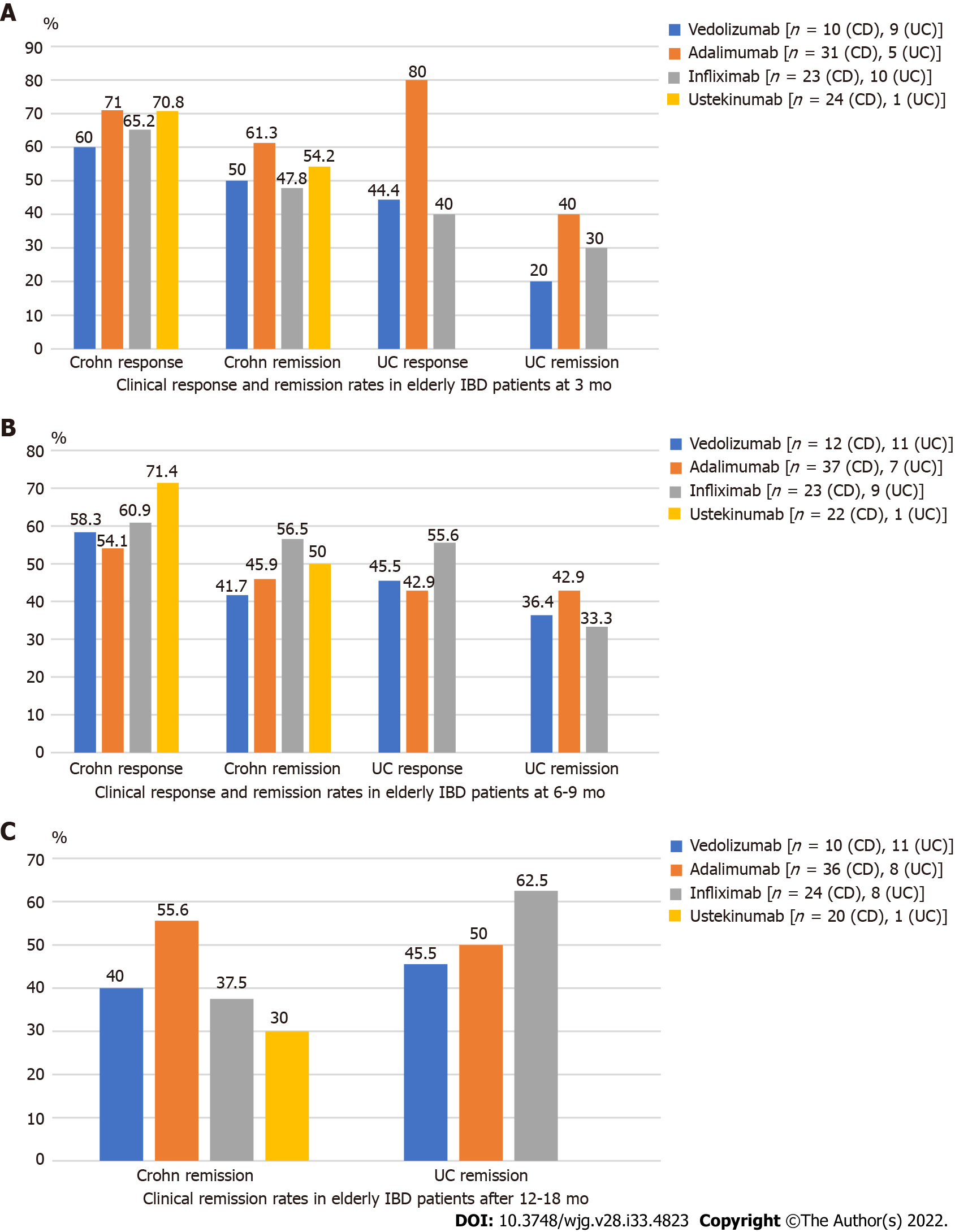

Figure 2A (see appendix section) shows the rates of clinical response and remission in elderly IBD patients treated with different biologicals according to HBI or Mayo scores at 3 mo. When assessing the clinical response in patients with CD, 71% of the patients on ADAL, 70% on UST, 65.2% on IFX and 60% on VDZ achieved clinical response at 3 mo. Regarding clinical remission in CD at 3 mo, 61.3% of patients on ADAL, followed by 54.2% on UST, 50% on VDZ and 47.8% on IFX achieved clinical remission. When looking at clinical response at 3 mo in patients with UC, 80% of the patients on ADAL, followed by VDZ with 44.4% and IFX with 40% responded. With regards to clinical remission at 3 mo, 40% patients on ADAL achieved clinical remission, 30% on IFX and 20% on VDZ.

The rates of clinical remission in elderly IBD patients treated with different biologicals according to HBI or Mayo scores at 6-9 mo are show in Figure 2B (see appendix section). Regarding clinical response in CD, 71.4% of patients on UST achieved clinical response at 6-9 mo, followed by 60.9 % on IFX, 58.3% on VDZ and 54.1% on ADAL. As for clinical remission in CD, 56.5% of patients on IFX, 50% on UST, 45.9% on ADAL and 41.7% on VDZ achieved clinical remission at 6-9 mo. When evaluating clinical response in UC, 55.6% of patients on IFX, followed by 45.5% on VDZ, 42.9% on ADAL reached clinical response at 6-9 mo. As for clinical remission in UC, 42.9% of patients on ADAL, 36.4% on VDZ and 33.3% on IFX achieved this outcome.

The rates of clinical remission in elderly IBD patients treated with different biologicals according to HBI or Mayo scores after 12-18 mo are presented in Figure 2C (see appendix section). Regarding clinical remission in patients with CD, 55.6% of patients on ADAL, followed by 40% on VDZ, 37.5% on IFX and 30% on UST achieved remission. As for clinical remission in patients with UC, approximately 62.5% of patients on IFX, followed by 50% on ADAL and 45.5% on VDZ achieved remission. Clinical response and remission rates were not significantly different across biologicals in either CD or UC at any time points (P = ns for each assessment), as shown in Figure 2 (see appendix section). Given the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of standardization of the collected measurements for endoscopic and biomarkers, the statistical analysis was inconclusive, therefore the data is not presented.

The major finding of our study was that the drug sustainability and safety of the different biologicals were not significantly different in a large real-world, elderly IBD cohort treated in this single tertiary IBD center. Peyrin-Biroulet et al[18] evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of anti-TNF in IBD patients, showing no difference in the frequency of mortality, malignancies and serious infections between anti-TNF and control group. Similarly, Lichtenstein et al[19] reported that the occurrence of death was similar between patients treated with anti-TNF and those who received other treatments only; however, an increased risk of infections was seen in patients treated with IFX. Borren and Ananthakrishnan[20] reported that older age was associated with an increased risk of malignancy compared to younger age. Elderly patients on biologics had a 3-fold increase in risk of infection compared to those who were not using biologics, yet there were no significant differences in odds of malignancy or mortality compared to older patients that were not using biologics.

Regarding efficacy and safety profile of biological therapy in the elderly patients, Asscher et al[21]. assessed the safety and effectiveness of anti-TNF therapy in IBD patients over 60 years. Elderly patients on anti-TNF therapy have an increased risk of serious infections compared with elderly IBD patients who are not on anti-TNF therapy, not compared to younger patients who receive anti-TNF, though. However, comorbidity has been shown to be an indicator of SAE in patients exposed to anti-TNF. Effectiveness was similar between elderly and younger patients. Lobatón et al[9] also evaluated efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in an elderly IBD population and showed a worse short-term clinical response to anti-TNFs at 10 wk after anti-TNF initiation, meaning that the probability of drug discontinuation during the follow-up (whatever the reason) was higher; but when excluding primary non response, this proportion became similar between the two groups. No differences were found in long-term efficacy among the initial responders (79.5% vs 82.8%; P = 0.64). As for safety, a higher risk of SAE was found in elderly IBD patients treated with anti-TNFs (risk ratio = 4.7; P < 0.001) compared to the younger subgroup[9]. Along with that, our study also reported statistically similar rates of 3 mo clinical response and 6-12 mo clinical response and remission among the four types of biologics studied (ADAL, IFX, VDZ and UST). Regarding safety, time to AE and to infection were also not statistically different.

The efficacy and safety of the anti-TNFs are extensively studied, less real world or comparative data are available for the new biologicals. In the landmark clinical trials, they appeared to be a safer option compared to the anti-TNFs, although in indirect comparisons. Recently, comparative efficacy and safety data became available in IBD patients. The SEAVUE study compared UST with ADAL for induction and maintenance of biological-naïve patients with moderate to severe CD. With regards to safety, 34.0% of UST-treated and 40.5% of the ADAL-treated patients had infections, 2.6% and 7.2% had SAEs, and 6.3% and 11.3% had AEs leading to therapy discontinuation in non-elderly IBD patients[22]. VARSITY trial compared VDZ with ADAL in patients with moderately to severely active UC, mainly patients without previous exposure to biologics. Numerical differences were observed in the reported AEs. Of note, the exposure-adjusted incidence rate of infection was 23.4 per 100 patients-year in the VDZ group and 34.6 per 100 patients-year in the ADAL group[23].

As for the elderly IBD population on new biologicals, there is still a paucity of data concerning efficacy and safety from real world studies. Cohen et al[24] evaluated the efficacy and safety of VDZ in elderly IBD patients compared to non-elderly patients. Equal effectiveness in both groups was reported; however, there was a higher risk of infections among the elderly on VDZ, which could be related to age and due to underlying diseases[24]. Garg et al[25] evaluated the safety and efficacy of UST in elderly CD patients. Efficacy and safety were similar in this relatively small cohort in elderly and non-elderly IBD patients; elderly patients were less likely severe, though, and both groups had 95% previous exposure to biologics. Furthermore, the mucosal healing rates observed in the elderly cohort were in check with other real-world studies performed in non-elderly IBD patients. As for safety, UST use in elderly IBD was not associated with higher rates of infusion reaction, infections, or postoperative complications as compared to the non-elderly patients[25]. In line with these studies, ours showed no significant difference in time to AEs and infection among elderly IBD patients treated with anti-TNF, VDZ and UST.

The strength of our study is that represents a single center cohort with harmonized treatment and follow-up strategies across IBD specialists. In addition, a complex analysis of effectiveness and safety was performed in a relatively large elderly IBD cohort. However, the present study has limitations. First, there was a relatively low number of elderly patients on new biological therapies. Second, it consists of a retrospective cohort with intrinsic problems of accuracy and potential biases such as recall bias and reporting bias, specially of AEs and mild infections, which patients may not have announced or may not have been documented. Third, follow-up on biomarkers, fecal calprotectin and endoscopy were not uniform for timing. Fourth and last, rates of previous exposure to biologicals were different for new biologics vs anti-TNFs.

Current biologic therapies were not different concerning drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety in the elderly IBD population. Based on these results, a preferred sequencing order among biologicals for this specific population is not possible to be suggested thus, larger studies in elderly IBD population are warranted.

Biologic therapy resulted in a significant positive impact on the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) however data on the efficacy and side effects of these therapies in the elderly is scant.

To further evaluate and develop more studies regarding treatment efficacy and safety of biological therapies in a specific and sensitive population, such as the elderly IBD patients, since there is not much evidence about it on medical literature so far.

Retrospectively evaluate the drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety of the biologic therapies in the elderly IBD population.

Consecutive elderly (≥ 60 years old) IBD patients, treated with biologics [infliximab (IFX), adalimumab (ADAL), vedolizumab (VDZ), ustekinumab (UST)] followed at the McGill University Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Center were included between January 2000 and 2020. Efficacy was measured by clinical scores at 3, 6-9 and 12-18 mo after initiation of the biologic therapy. Patients completing induction therapy were included. Adverse events (AEs) or serious AEs were collected during and within three months of stopping of the biologic therapy.

A total of 147 elderly patients with IBD were identified and treated with biologicals during the study period, including 109 with Crohn’s disease and 38 with ulcerative colitis. Patients received the following biologicals: IFX (28.5%), ADAL (38.7%), VDZ (15.6%), UST (17%). The mean duration of biological therapy was 157.5 (SD = 148) wk. Parallel steroid therapy was given in 34% at baseline, 19% at 3 mo, 16.3% at 6-9 mo and 6.5% at 12-18 mo. The remission rates at 3, 6-9 and 12-18 mo were not significantly different among biological therapies. Kaplan-Meyer analysis did not show statistical difference for drug sustainability (P = 0.195), time to adverse event (P = 0.158) or infection rates (P = 0.973) between the four studied biologicals. The most common AEs that led to drug discontinuation were loss of response, infusion/injection reaction and infection.

Current biologics were not different regarding drug sustainability, effectiveness, and safety in the elderly IBD population. Therefore, it is not possible to suggest a preferred sequencing order among biologics.

The authors expect that this article may help other IBD physicians and gastroenterologists in their decision process for treating elderly IBD patients with biological therapy.

| 1. | Jeuring SF, van den Heuvel TR, Zeegers MP, Hameeteman WH, Romberg-Camps MJ, Oostenbrug LE, Masclee AA, Jonkers DM, Pierik MJ. Epidemiology and Long-term Outcome of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosed at Elderly Age-An Increasing Distinct Entity? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1425-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rozich JJ, Luo J, Dulai PS, Collins AE, Pham L, Boland BS, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Disease- and Treatment-related Complications in Older Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Comparison of Adult-onset vs Elderly-onset Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1215-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Donaldson T, Lasch K, Yajnik V. Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Elderly Patient: Challenges and Opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:882-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:459-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hruz P, Juillerat P, Kullak-Ublick GA, Schoepfer AM, Mantzaris GJ, Rogler G; on behalf of Swiss IBDnet, an official working group of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Management of the Elderly Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patient. Digestion. 2020;101 Suppl 1:105-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Everhov ÅH, Halfvarson J, Myrelid P, Sachs MC, Nordenvall C, Söderling J, Ekbom A, Neovius M, Ludvigsson JF, Askling J, Olén O. Incidence and Treatment of Patients Diagnosed With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases at 60 Years or Older in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:518-528.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mak JWY, Lok Tung Ho C, Wong K, Cheng TY, Yip TCF, Leung WK, Li M, Lo FH, Ng KM, Sze SF, Leung CM, Tsang SWC, Shan EHS, Chan KH, Lam BCY, Hui AJ, Chow WH, Ng SC. Epidemiology and Natural History of Elderly-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results From a Territory-wide Hong Kong IBD Registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Charpentier C, Salleron J, Savoye G, Fumery M, Merle V, Laberenne JE, Vasseur F, Dupas JL, Cortot A, Dauchet L, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lerebours E, Colombel JF, Gower-Rousseau C. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2014;63:423-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lobatón T, Ferrante M, Rutgeerts P, Ballet V, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:441-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheng D, Cushing KC, Cai T, Ananthakrishnan AN. Safety and Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists in Older Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: Patient-Level Pooled Analysis of Data From Randomized Trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:939-946.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, Fox I, Milch C, Sankoh S, Wyant T, Xu J, Parikh A; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1971] [Article Influence: 151.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Jacobstein D, Lang Y, Friedman JR, Blank MA, Johanns J, Gao LL, Miao Y, Adedokun OJ, Sands BE, Hanauer SB, Vermeire S, Targan S, Ghosh S, de Villiers WJ, Colombel JF, Tulassay Z, Seidler U, Salzberg BA, Desreumaux P, Lee SD, Loftus EV Jr, Dieleman LA, Katz S, Rutgeerts P; UNITI–IM-UNITI Study Group. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1467] [Cited by in RCA: 1449] [Article Influence: 144.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yajnik V, Khan N, Dubinsky M, Axler J, James A, Abhyankar B, Lasch K. Efficacy and Safety of Vedolizumab in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease Patients Stratified by Age. Adv Ther. 2017;34:542-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Busquets N, Carmona L, Surís X. [Systematic review: safety and efficacy of anti-TNF in elderly patients]. Reumatol Clin. 2011;7:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2449] [Article Influence: 122.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39738] [Article Influence: 1018.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, Dubois C, Rutgeerts P. Correlation between the Crohn's disease activity and Harvey-Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn's disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:357-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Price S, Langholff W, Londhe A, Sandborn WJ. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn's disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT™ registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1409-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Borren NZ, Ananthakrishnan AN. Safety of Biologic Therapy in Older Patients With Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1736-1743.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Asscher VER, van der Vliet Q, van der Aalst K, van der Aalst A, Brand EC, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Oldenburg B, Pierik MJ, van Tuyl B, Mahmmod N, Maljaars PWJ, Fidder HH; Dutch ICC. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; comorbidity, not patient age, is a predictor of severe adverse events. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:2331-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Irving PM, Sands BE, Hoops T, Izanec JL, Gao LL, Gasink C, Greenspan A, Allez M, Danese S, Hanauer SB, Jairath V, Kuehbacher T, Lewis JD, Loftus EV, Mihaly JrE, Panaccione R, Scherl E, Shchukina O, Sandborn WJ. OP02 Ustekinumab vs adalimumab for induction and maintenance therapy in Moderate-to-Severe Crohn’s Disease: The SEAVUE study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:S001-S002. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Danese S, Colombel JF, Törüner M, Jonaitis L, Abhyankar B, Chen J, Rogers R, Lirio RA, Bornstein JD, Schreiber S; VARSITY Study Group. Vedolizumab versus Adalimumab for Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cohen NA, Plevris N, Kopylov U, Grinman A, Ungar B, Yanai H, Leibovitzh H, Isakov NF, Hirsch A, Ritter E, Ron Y, Shitrit AB, Goldin E, Dotan I, Horin SB, Lees CW, Maharshak N. Vedolizumab is effective and safe in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients: a binational, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:1076-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Garg R, Aggarwal M, Butler R, Achkar JP, Lashner B, Philpott J, Cohen B, Qazi T, Rieder F, Regueiro M, Click B. Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Elderly Crohn's Disease Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:3138-3147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigues AT, Brazil; Sitkin S, Russia S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ