Published online Feb 21, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i7.654

Peer-review started: November 25, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 20, 2020

Accepted: January 13, 2021

Article in press: January 13, 2021

Published online: February 21, 2021

Processing time: 86 Days and 14.1 Hours

The most effective treatment for advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension is liver transplantation (LT). However, splenomegaly and hypersplenism can persist even after LT in patients with massive splenomegaly.

To examine the feasibility of performing partial splenectomy during LT in patients with advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism.

Between October 2015 and February 2019, 762 orthotopic LTs were performed for patients with end-stage liver diseases in Tianjin First Center Hospital. Eighty-four cases had advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism. Among these patients, 41 received partial splenectomy during LT (PSLT group), and 43 received only LT (LT group). Patient characteristics, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative outcomes were retrospectively analyzed and compared between the two groups.

The incidence of postoperative hypersplenism (2/41, 4.8%) and recurrent ascites (1/41, 2.4%) in the PSLT group was significantly lower than that in the LT group (22/43, 51.2%; 8/43, 18.6%, respectively). Seventeen patients (17/43, 39.5%) in the LT group required two-stage splenic embolization, and further splenectomy was required in 6 of them. The operation time and intraoperative blood loss in the PSLT group (8.6 ± 1.3 h; 640.8 ± 347.3 mL) were relatively increased compared with the LT group (6.8 ± 0.9 h; 349.4 ± 116.1 mL). The incidence of postoperative bleeding, pulmonary infection, thrombosis and splenic arterial steal syndrome in the PSLT group was not different to that in the LT group, respectively.

Simultaneous PSLT is an effective treatment and should be performed in patients with advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism to prevent postoperative persistent hypersplenism.

Core Tip: In this article, for the first time, we describe partial splenectomy during liver transplantation (PSLT) in patients with advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism. PSLT can effectively alleviate the severity of postoperative hypersplenism and ascites in megalosplenia patients.

- Citation: Jiang WT, Yang J, Xie Y, Guo QJ, Tian DZ, Li JJ, Shen ZY. Simultaneous partial splenectomy during liver transplantation for advanced cirrhosis patients combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(7): 654-665

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i7/654.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i7.654

Liver cirrhosis is the leading cause of liver disease related morbidity and mortality worldwide and is often accompanied by portal hypertension and splenomegaly[1]. The most effective treatment for advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension is liver transplantation (LT)[2]. Splanchnic hemodynamics change dramatically after LT, including improved portal outflow resistance, decreased portal vein pressure, and movement of accumulated blood from viscera to the systemic circulation. These changes significantly increase portal vein flow, gradually improve spleen congestion, and further ameliorate splenomegaly and hypersplenism[3].

However, splenomegaly and hypersplenism can persist even after LT in patients with massive splenomegaly[4]. Persistent hypersplenism-related pancytopenia may interfere with the management of immunosuppressive therapy[5]. Splenomegaly may further result in excessive portal pressure or splenic artery steal syndrome. The resulting decrease in hepatic arterial inflow can then affect liver graft function[6]. The most common therapies for splenomegaly and hypersplenism are total splenectomy during LT (TSLT) and selective splenic artery embolization (SAE) after LT[7], but they have considerable limitations.

TSLT is associated with increased operative time and additional blood loss[6]. Furthermore, TSLT increases the risk of postoperative complications, such as overwhelming post-splenectomy infection syndrome (OPIS), reactive thrombocytosis, and portal venous system thrombosis[8,9]. It remains controversial whether simultaneous splenectomy during LT is beneficial in these patients.

SAE after LT is a secondary treatment used in addition to surgery to manage hypersplenism in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension[7]. However, SAE after LT results in a high risk of infection[10]. Patients with cirrhosis are often debilitated and may have compromised immunity. The immune-compromised nature of a transplant recipient magnifies the risk of major infectious complications. Serious complications may occur after SAE, such as abdominal infection, pancreatitis, splenic abscess, and splenic rupture. Post-embolization syndrome, characterized by fever and/or abdominal pain, occurs in up to 78% of patients following SAE[11]. Other disadvantages of SAE include high recurrence rates, and difficulty accessing the embolic area[12].

Cirrhosis with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism is common, yet satisfactory treatment is lacking[13]. In our center, splenectomy during LT has been used for more than ten years, but was abandoned due to uncontrollable postoperative complications, such as portal vein thrombosis, insufficient portal vein flow, and OPIS[6,8,9]. Later, we performed LT without intraoperative intervention[8]. If hypersplenism or portal hypertension persisted after surgery, then we performed SAE[7]. However, we found that this process increased the risk of infection due to extensive splenic infarction and prolonged the patient’s discharge time. A method that limits the extent of splenectomy and spares splenic function is necessary.

To realize this need, we first proposed and designed the procedure of partial splenectomy during LT (PSLT), which is an all-in-one treatment for post-LT complications. In this article, we demonstrate the role of PSLT in the treatment of advanced cirrhosis with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism.

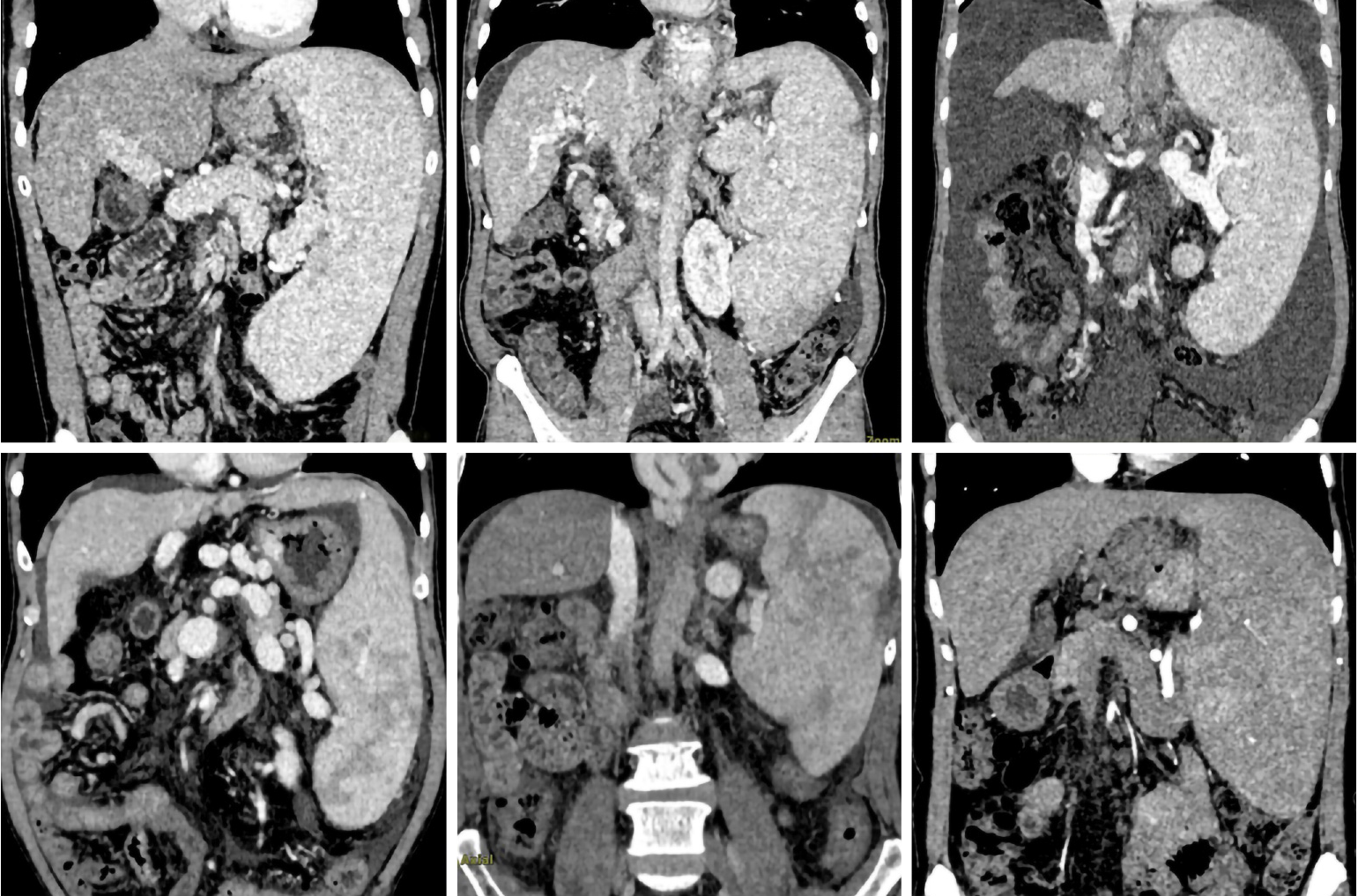

Between October 2015 and February 2019, 762 cases of classic orthotopic LT were performed at our institution. Among these, there were 84 cases of advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly (Figure 1) and hypersplenism. Forty-one cases received PSLT (PSLT group), and 43 cases received only LT with no intervention (LT group). Patient characteristics, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative outcomes were compared between the LT and PSLT groups and retrospectively analyzed. All patients were followed-up regularly by the same surgical team. No patients were lost during follow-up. The last census date for the study was October 31, 2020. All grafts used for LT were obtained from deceased donors, and no organs from executed prisoners were used. All deceased donations complied with the China Organ Donation Program. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin First Central Hospital.

The inclusion criteria for the 2 groups were the same and are as follows: (1) Indication for LT; (2) The primary disease was benign liver disease or liver cancer meeting the Milan criteria; (3) Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score < 25 and the patient was in a stable condition; and (4) Severe splenomegaly (spleen volume > 1000 mL) and hypersplenism (platelet count < 50 × 109/L). In our previous studies, hypersplenism persisted after LT in most patients with a spleen volume >1000 mL and platelet count < 50 × 109/L[14]. The exclusion criteria included: (1) MELD score > 25; (2) Severe perisplenic adhesions; (3) Accompanying splenic tumor; and (4) Spleen volume < 1000 mL or platelet count > 50 × 109/L.

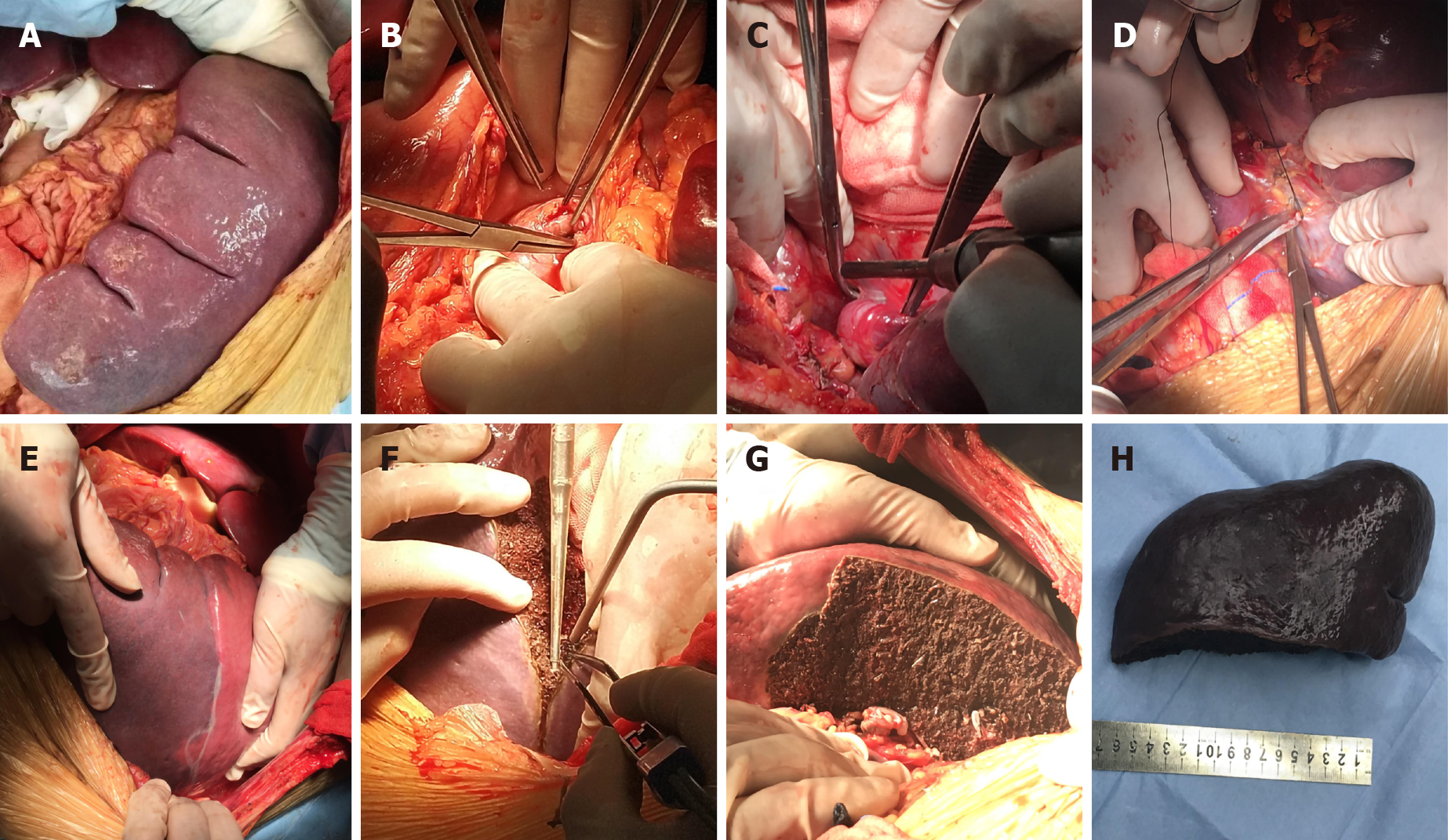

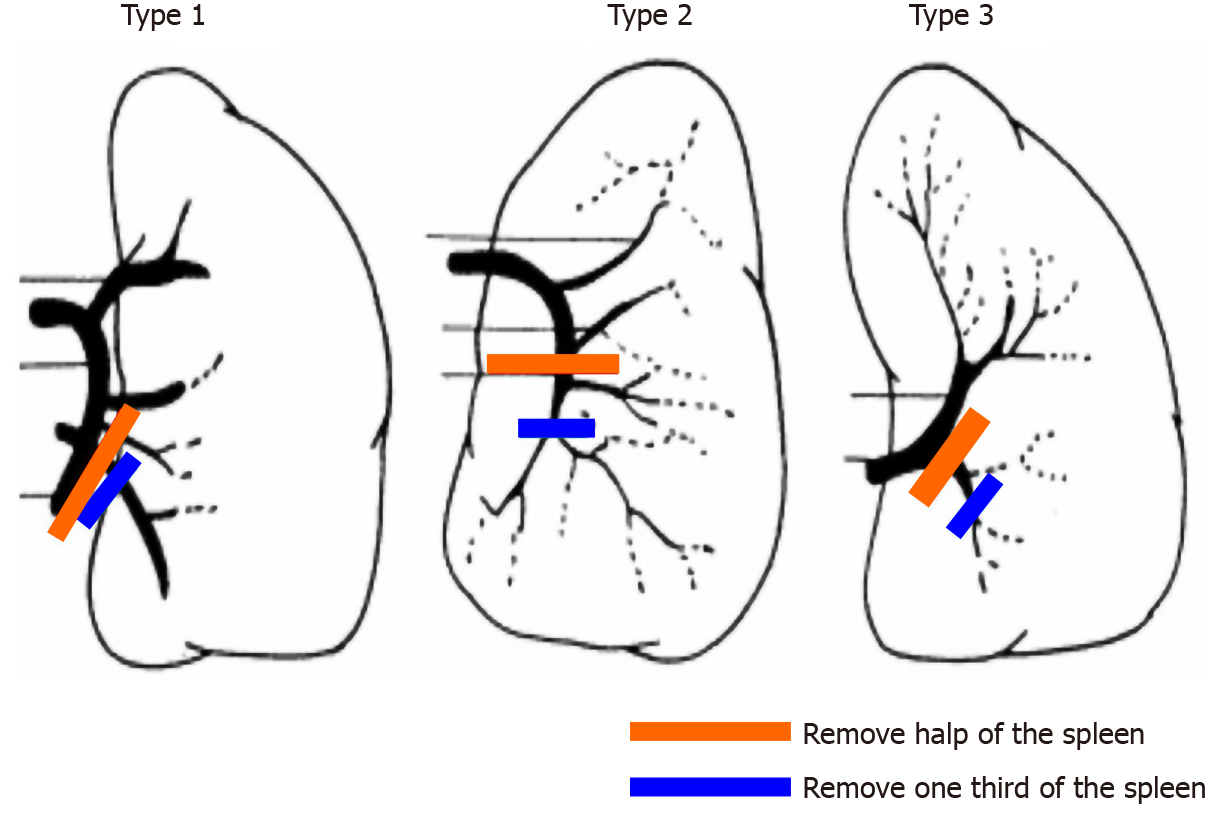

Partial splenectomy was performed after classic orthotopic LT (caval replacement) as follows: The primary splenic artery was isolated, exposed, and prepared for clamping to prevent uncontrolled bleeding (Figure 2A and B). According to the anatomic classification of the spleen vessels evaluated by preoperative spiral computed tomography (CT) three-dimensional reconstruction, hilar vessels from the lower pole of the spleen were selectively closed with a vascular clamp (usually, half or one third of the spleen was removed as shown in Figure 3; and the cutting planes defined for spleen resection should be maintained above the costal margin; meanwhile, adjusted as per the intraoperative flow by Doppler ultrasound: portal vein flow should be more than 100 mL/100 g/min and hepatic artery blood flow should be more than 35 mL/100 g/min). The relevant ischemic demarcation line was then observable (Figure 2E), and the resection was performed along the demarcation line (Figure 2F). A Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator and bipolar coagulation forceps were used to split the spleen. Hemostasis was performed along the resection line using surgical, bipolar coagulation, and argon beam (Figure 2G). Segmental hilar vessels were allowed to remain with the splenic remnant. Bleeding should be carefully avoided ensuring safety. The splenic artery was clamped with conventional forceps during the splenic incision, and the tube structure was clipped with titanium clamps. After repeated hemostasis, the splenic artery was opened again to assess the presence of hemostasis, and the drainage tube and hemostatic gauze were placed last.

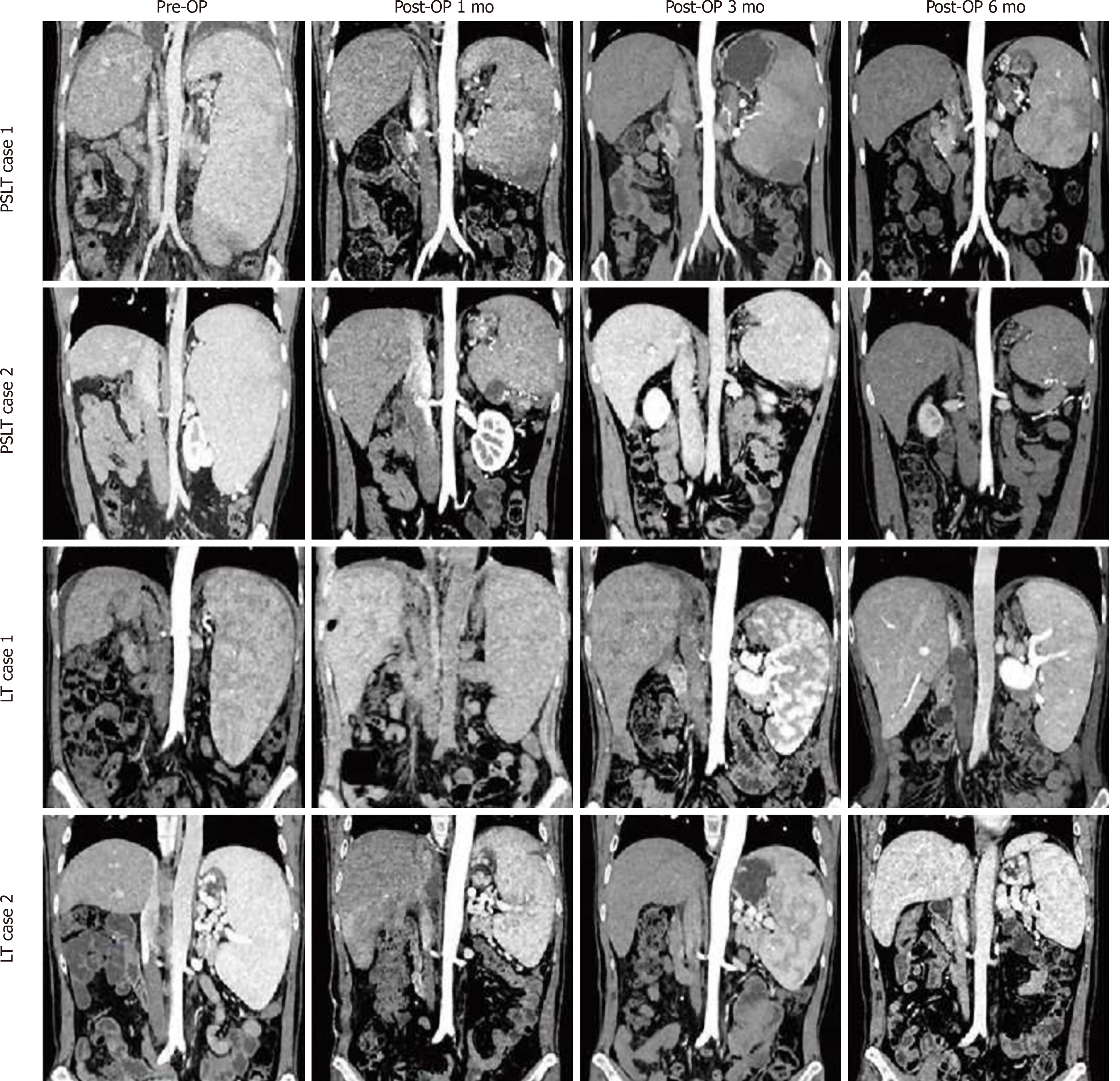

After LT, blood biochemistry was performed regularly to monitor liver function. Color Doppler ultrasound was reviewed every day for one week and every three days for one month to monitor the dynamic flow of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and vena cava. All patients were analyzed by the same senior color Doppler ultrasound operator. Enhanced CT was reexamined preoperatively and postoperatively at 1, 6, and 12 mo to measure spleen volume.

The Chi-square test, Fisher exact test, and paired t-test were used to compare patient characteristics, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative results in the LT group and PSLT group. All quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. SPSS 21.0 was used for statistical analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there was no difference in preoperative characteristics between the two groups. The MELD scores in the LT group and PSLT group were 19.4 ± 4.9 and 20.7 ± 4.6 points, respectively, and the Graft /Recipient Weight Ratios (%) were 1.4 ± 0.5 and 1.4 ± 0.6, respectively. Preoperative spleen volumes in the LT group and PSLT group were 1665 ± 611 cm3 and 1711 ± 682 cm3, respectively, and platelet counts were 38.6 ± 14.7 × 103/mm3 and 36.9 ± 14.1 × 103/mm3, respectively. Preoperative portal vein blood flow in the LT and PSLT groups was 12.4 ± 3.9 and 11.8 ± 3.7 cm/s, respectively, and preoperative hepatic arterial blood flow in the two groups was 40.3 ± 22.1 and 40.9 ± 21.7 cm/s, respectively.

| LT group (n = 43) | PSLT group (n = 41) | P value | |

| Gender (male/female) | 27/16 | 28/13 | 0.651 |

| Age, yr | 49.2 ± 12.8 | 52.7 ± 13.1 | 0.219 |

| Indication for transplantation | |||

| Hepatitis B cirrhosis | 19 | 21 | 0.662 |

| Hepatic malignancy | 10 | 8 | 0.792 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 8 | 6 | 0.772 |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 2 | 3 | 0.672 |

| etc. | 4 | 3 | > 0.99 |

| MELD score at transplantation | 19.4 ± 4.9 | 20.7 ± 4.6 | 0.214 |

| PreOP biology | |||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 133.0 ± 106.9 | 128.5 ± 97.2 | 0.841 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 96.1 ± 72.6 | 82.6 ± 66.3 | 0.377 |

| INR | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.447 |

| Plasma ammonia (μmol/L) | 59.7 ± 21.5 | 57.6 ± 23.4 | 0.669 |

| PreOP platelet count, 103/mm3 | 38.6 ± 14.7 | 36.9 ± 14.1 | 0.590 |

| PreOP spleen volume, cm3 | 1665 ± 611 | 1711 ± 682 | 0.745 |

| PreOP PV flow, cm/s | 12.4 ± 3.9 | 11.8 ± 3.7 | 0.472 |

| PreOP HA flow, cm/s | 40.3 ± 22.1 | 40.9 ± 21.7 | 0.453 |

| LT group (n = 43) | PSLT group (n = 41) | P value | |

| Gender (male/female) | 31/12 | 28/13 | > 0.99 |

| Age, yr | 42.6 ± 16.3 | 44.5 ± 15.9 | 0.665 |

| Cause of death | |||

| Cerebral trauma | 24 | 22 | > 0.99 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 10 | 8 | 0.792 |

| Brain tumor (glioma) | 4 | 5 | 0.735 |

| Hypoxic brain injury | 2 | 3 | 0.672 |

| etc. | 3 | 3 | > 0.99 |

| ICU stay, d | 2.71 ± 2.05 | 2.83 ± 2.24 | 0.798 |

As summarized in Table 3, the total operation time in the PSLT group (8.6 ± 1.3 h) was longer than that in the LT group (6.8 ± 0.9 h), and the time required for partial splenectomy was 1.8 ± 0.3 h (range 1.6 to 2.1 h). Intraoperative blood loss in the PSLT group (640.8 ± 347.3 mL) was more than that in the LT group (349.4 ± 116.1 mL), and blood loss during partial splenectomy was 85.6 ± 79.2 mL (range 50 to 350 mL). The weight of excised spleen in the PSLT group was 787 ± 371.4 g (range 342 to 1806 g). The mean portal flow in the LT group and PSLT group increased from 12.4 ± 3.9 cm/s and 11.8 ± 3.7 cm/s preoperative to 47.6 ± 14.1 cm/s and 42.7 ± 13.8 cm/s postoperative, respectively. The mean hepatic artery blood flow in the PSLT group (49.3 ± 13.6 cm/s) was higher than that in the LT group (42.6 ± 11.4 cm/s).

| LT group (n = 43) | PSLT group (n = 41) | P value | |

| Operating time, h | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Time for PS | 1.8 ± 0.3 | ||

| Blood loss, mL | 349.4 ± 116.9 | 440.8 ± 141.3 | 0.002 |

| During PS | 85.6 ± 79.2 | ||

| PostOP HA flow, cm/s | 42.6 ± 11.4 | 49.3 ± 13.6 | 0.016 |

| PostOP PV flow, cm/s | 47.6 ± 14.1 | 42.7 ± 13.8 | 0.022 |

| Weight of PS, g | 787 ± 371.4 | ||

| Percentage of PS, (n) | |||

| Half of spleen | 23 | ||

| Third of spleen | 18 |

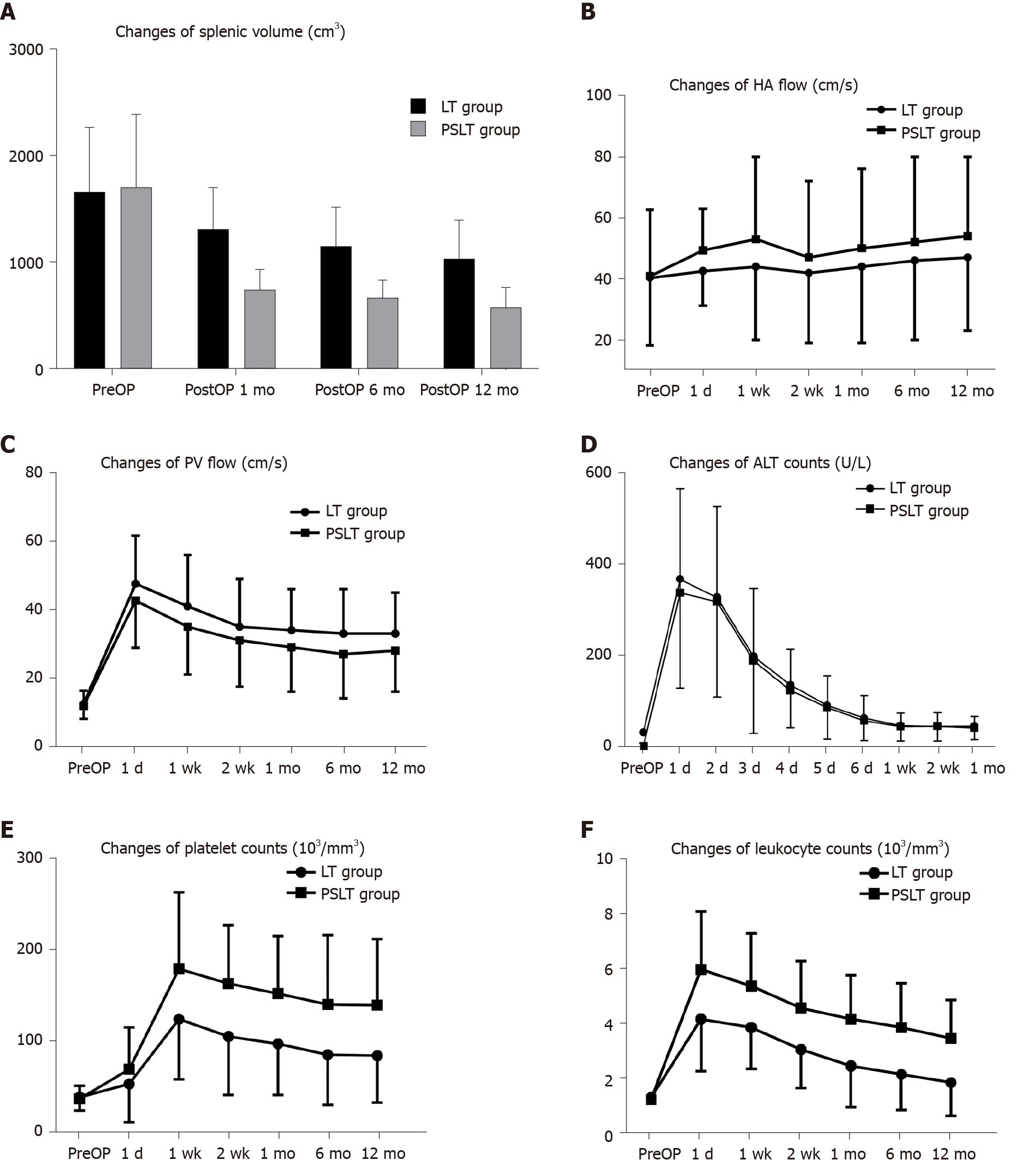

As shown in Figure 4A, spleen volume in the LT group and PSLT group decreased from 1665 ± 611 cm3 and 1711 ± 682 cm3 preoperative to 1316 ± 397 cm3 and 745 ± 189 cm3 at postoperative 1 mo, 1157 ± 361 cm3 and 668 ± 174 cm3 at postoperative 6 mo, and 1041 ± 364 cm3 and 581 ± 179 cm3 at postoperative 12 mo, respectively. Postoperative blood flow in the hepatic artery and portal vein were monitored by color Doppler ultrasound. Compared with the LT group, hepatic artery flow increased in the PSLT group and portal vein flow decreased (Figure 4B and C).

In the PSLT group, platelet counts increased to the peak level at postoperative day 14, and leukocyte counts increased to the peak value at postoperative day 7. Both platelet counts and leukocyte counts in the PSLT group increased faster than those in the LT group, resulting in a significant difference between the groups. Platelet count was 139.4 ± 72.4 × 103/mm3 in the PSLT group and 84.1 ± 51.5 × 103/mm3 in the LT group at postoperative 12 mo (P < 0.001). Leukocyte count was 3.6 ± 1.4 × 103/mm3 in the PSLT group and 1.9 ± 0.8 × 103/mm3 in the LT group at postoperative 12 mo (P < 0.001).

Postoperative complications in the two groups are summarized in Table 4. The incidence of postoperative hypersplenism (2/41, 4.8%) and recurrent ascites (1/41,2.4%) in the PSLT group were significantly lower than that in the LT group (22/43,51.2%; 8/43, 18.6%, respectively). Seventeen patients (17/43, 39.5%) in the LT group required multiple partial splenic embolization (PSE) to relieve postoperative persistent hypersplenism in 15 and refractory ascites in 2. Six of them required further splenectomy after PSE, 2 patients due to persistent severe splenic infarction syndrome, 2 patients due to persistent hypersplenism despite embolization, 1 patient due to splenic abscess with repeated infection after PSE, and 1 patient due to hypersplenism and persistent abdominal pain after PSE. In the PSLT group, no patient underwent two-stage splenic embolization or surgery for postoperative persistent hypersplenism.

| LT group (n = 43) | PSLT group (n = 41) | P value | |

| Postoperative hypersplenism | 22 (51.1) | 2 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| Recurrent ascites | 8 (18.6) | 1 (2.4) | 0.029 |

| Reoperation due to post-op bleeding | 2 (4.6) | 3 (7.3) | 0.672 |

| Postoperative pulmonary infection | 5 (11.6) | 4 (9.7) | > 0.99 |

| Post-op thrombosis | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.4) | > 0.99 |

| Splenic arterial steal syndrome | 4 (9.3) | 0 | 0.116 |

| Two-stage splenic embolization | 17 (39.5) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Further splenectomy | 6 (13.9) | 0 | 0.026 |

Other postoperative complications requiring reoperation were postoperative bleeding (n = 3), pulmonary infection (n = 4), thrombosis (n = 1) and splenic arterial steal syndrome (n = 0) in the PSLT group, which were similar to those (n = 2, n = 5, n = 1, n = 4, respectively) in the LT group. In-hospital mortality did not occur in either group.

Partial splenectomy can be used to treat severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism, and its safety and efficacy have been confirmed[15,16]. Partial splenectomy reduces spleen volume and alleviates the symptoms of hypersplenism while maintaining the immunological functions of the spleen. These beneficial effects have also been confirmed in animal models. However, so far there are no reports on the application of partial splenectomy in LT.

In this article, we described the PSLT procedure for advanced cirrhosis with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism. Hypersplenism/splenomegaly can lead to post-LT complications and PSLT could offer an all-in-one intervention to mitigate these clinically-relevant issues. As our data showed, although partial splenectomy took 1.5-2 h and resulted in blood loss of 50-350 mL, the PSLT group showed significant improvement in ascites and hypersplenism after transplantation, and no recurrence of splenomegaly or hypersplenism was observed during follow-up. In the LT group, the average spleen volume after 12 mo is still greater than 1000 cm3, and 51% of the patients will continue to have hypersplenism. Most of them must undergo the second stage of splenic embolization or splenectomy to improve hematological parameters to allow the use of other myelosuppressive drugs.

Most previous studies on partial splenectomy in patients with cirrhosis advocated subtotal splenectomy and reported that approximately 90% of the spleen can be removed to ensure a curative effect[16,17]. However, the magnitude of PSLT was far less, and the therapeutic effect was also significant. In our study, we usually remove half or one third of the spleen according to the splenic hilum vessel anatomy, as shown in Figure 3. We also try to maintain the cutting planes of spleen resection above the costal margin to protect the spleen section. In addition, we found that intraoperative resection ratio and splenic volume reduction ratio reassessed by CT scan after surgery were significantly different (Figure 5). The reduction degree of spleen volume varies by patient, and may be related to the history of liver disease and the severity of splenic hyperplasia. Patients with a long history of cirrhosis and severe splenic hyperplasia are more likely to have poor relief of hypersplenism after LT.

However, the present study is retrospective and only included relatively few patients from a single center. Large multicenter studies with long-term follow-up are necessary. In addition, we have not applied this procedure in living donor LT patients. Further studies are needed to investigate whether partial splenectomy during living donor LT can reduce portal vein perfusion and prevent small spleen syndrome, as well as treat hypersplenism.

In conclusion, PSLT solves a series of problems such as end-stage liver disease, hypersplenism, splenomegaly and hemodynamic disorder all at once, so patients do not need to receive two-stage splenic embolization or splenectomy. However, PSLT requires up to 25% longer operation time and the need for blood products, which would raise concerns in transplant surgeons. Appropriate patient selection is necessary to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks. According to our experience, patients with preoperative severe splenomegaly (spleen volume > 1000 mL) and hypersplenism (platelet count < 50 × 109/L) are more likely to have intractable hypersplenism after LT, and PSLT is recommended. PSLT is not recommended when the patient has a MELD score > 25, severe perisplenic adhesions, accompanied by splenic tumor, splenic volume < 1000 mL or platelet count > 50 × 109/L.

The most effective treatment for advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension is liver transplantation (LT). However, splenomegaly and hypersplenism can persist even after LT in patients with massive splenomegaly. Persistent hypersplenism-related pancytopenia may interfere with the management of immunosuppressive therapy. Splenomegaly may further result in excessive portal pressure or splenic artery steal syndrome. The resulting decrease in hepatic arterial inflow can then affect liver graft function.

The most common therapies for splenomegaly and hypersplenism are total splenectomy during LT and selective splenic artery embolization after LT, but they have considerable limitations. Cirrhosis with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism is common, yet satisfactory treatment is lacking. To realize this need, we first proposed and designed the procedure of partial splenectomy during LT (PSLT), which is an all-in-one treatment for post-LT complications.

To examine the feasibility of performing partial splenectomy during LT in patients with advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism.

Between October 2015 and February 2019, 762 cases of classic orthotopic LT were performed at our institution. Among these, there were 84 cases of advanced cirrhosis combined with severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism. Forty-one cases received PSLT (PSLT group), and 43 cases received only LT with no intervention (LT group). Patient characteristics, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative outcomes were compared between the LT and PSLT groups and retrospectively analyzed.

The incidence of postoperative hypersplenism and recurrent ascites in the PSLT group was significantly lower than that in the LT group. Seventeen patients in the LT group required two-stage splenic embolization, and further splenectomy was required in 6 of them. The operation time and intraoperative blood loss in the PSLT group were relatively increased compared with the LT group. The incidence of postoperative bleeding, pulmonary infection, thrombosis and splenic arterial steal syndrome in the PSLT group was similar to that in the LT group, respectively.

PSLT can reduce the incidence of postoperative hypersplenism and recurrent ascites, and reduce the risk of secondary splenic embolization and splenectomy, but the operation time and intraoperative blood loss were increased.

According to our experience, patients with preoperative severe splenomegaly and hypersplenism are more likely to have intractable hypersplenism after LT, and PSLT is recommended.

| 1. | Khanna R, Sarin SK. Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: Current and Emerging Perspectives. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:781-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kockerling D, Nathwani R, Forlano R, Manousou P, Mullish BH, Dhar A. Current and future pharmacological therapies for managing cirrhosis and its complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:888-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Mukhtar A, Dabbous H. Modulation of splanchnic circulation: Role in perioperative management of liver transplant patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1582-1592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Kawano F, Ishizaki Y, Yoshimoto J, Fujiwara N, Kawasaki S. Factors Affecting Persistent Splenomegaly After Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Using a Left Lobe. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:1946-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Molina Perez E, Fernández Castroagudín J, Seijo Ríos S, Mera Calviño J, Tomé Martínez de Rituerto S, Otero Antón E, Bustamante Montalvo M, Varo Perez E. Valganciclovir-induced leukopenia in liver transplant recipients: influence of concomitant use of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1047-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chezmar JL, Redvanly RD, Nelson RC, Henderson JM. Persistence of portosystemic collaterals and splenomegaly on CT after orthotopic liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:317-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | DuBois B, Mobley D, Chick JFB, Srinivasa RN, Wilcox C, Weintraub J. Efficacy and safety of partial splenic embolization for hypersplenism in pre- and post-liver transplant patients: A 16-year comparative analysis. Clin Imaging. 2019;54:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Golse N, Mohkam K, Rode A, Pradat P, Ducerf C, Mabrut JY. Splenectomy during whole liver transplantation: a morbid procedure which does not adversely impact long-term survival. HPB (Oxford). 2017;19:498-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Badawy A, Hamaguchi Y, Satoru S, Kaido T, Okajima H, Uemoto S. Evaluation of safety of concomitant splenectomy in living donor liver transplantation: a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2017;30:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ricci K, Asharf EH. The use of splenic artery embolization to maintain adequate hepatic arterial inflow after hepatic artery thrombosis in a split liver transplant recipient. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:241-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | report on dracunculiasis cases, January–October 2014. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89:587-588. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Koconis KG, Singh H, Soares G. Partial splenic embolization in the treatment of patients with portal hypertension: a review of the english language literature. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:463-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gangireddy VG, Kanneganti PC, Sridhar S, Talla S, Coleman T. Management of thrombocytopenia in advanced liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:558-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He J, Guo QJ, Xie Y, Zhang L, Tian DZ, Wang HH, Chen CY, Jiang WT. Application of image post -processing technique to measure spleen volume and evaluate the effect of orthotopic liver transplantation on relieving hypersplenism. Zhonghua Qiguan Yizhi Zazhi. 2019;40:107-11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Guan YS, Hu Y. Clinical application of partial splenic embolization. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:961345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chu H, Han W, Wang L, Xu Y, Jian F, Zhang W, Wang T, Zhao J. Long-term efficacy of subtotal splenectomy due to portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. BMC Surg. 2015;15:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Radević B, Jesić R, Sagić D, Perisić V, Nenezić D, Popov P, Ilijevski N, Dugalić V, Gajin P, Vucurević G, Radak Dj, Trebjesanin Z, Babić D, Kastratović D, Matić P. [Partial resection of the spleen and spleno-renal shunt in the treatment of portal hypertension with splenomegaly and hypersplenism]. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2002;49:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chairman of Organ Transplantation Branch, Chinese Medical Association; Director of China Human Organ Donation Management Center; Chief Expert of Organ Transplantation in the Core Group of China Central Health Commission; Visiting Professor, Department of Medicine, Daikyo University, Japan; President of China Research Hospital Association

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gelmini R S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ