Published online Oct 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i38.6501

Peer-review started: April 9, 2021

First decision: May 24, 2021

Revised: June 1, 2021

Accepted: September 6, 2021

Article in press: September 6, 2021

Published online: October 14, 2021

Processing time: 185 Days and 16.9 Hours

Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a rare primary intestinal T-cell lymphoma, previously known as enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma type II. MEITL is an aggressive T-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis and high mortality rate. The known major complications of MEITL are intestinal perforation and obstruction. Here, we present a case of MEITL that was diagnosed following upper gastrointestinal bleeding from an ulcerative duodenal lesion, with recurrence-free survival for 5 years.

A 68-year-old female was admitted to our hospital with melena and mild anemia. An urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed bleeding from an ulcerative lesion in the transverse part of the duodenum, for which hemostatic treatment was performed. MEITL was diagnosed following repeated biopsies of the lesion, and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) chemotherapy was administered. She achieved complete remission after eight full cycles of CHOP therapy. At the last follow-up examination, EGD revealed a scarred ulcer and 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography showed no abnormal FDG accumulation. The patient has been in complete remission for 68 mo after initial diagnosis.

To rule out MEITL, it is important to carefully perform histological examination when bleeding from a duodenal ulcer is observed.

Core Tip: Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a primary intestinal T-cell lymphoma with the known major complications of intestinal perforation and obstruction. We experienced a case of MEITL that was diagnosed after gastrointestinal bleeding from an ulcerative duodenal lesion, who survived for a long time after treatment. MEITL can present as gastrointestinal bleeding. In addition, although MEITL has a poor prognosis, patients with MEITL might survive for a long time if effective treatment is administered at an early stage. Therefore, it is important to perform thorough histological examination for the early diagnosis of MEITL in cases with bleeding duodenal ulcers.

- Citation: Ozaka S, Inoue K, Okajima T, Tasaki T, Ariki S, Ono H, Ando T, Daa T, Murakami K. Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma presenting as melena with long-term survival: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(38): 6501-6510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i38/6501.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i38.6501

Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a rare primary intestinal T-cell lymphoma newly defined by the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization, that was previously known as enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) type II[1]. It arises from intestinal intraepithelial T lymphocytes and tends to behave aggressively[2]. EATL was originally categorized into two major groups, EATL type I and EATL type II. EATL type I is now simply classified as EATL, and it is strongly associated with celiac disease and occurs in Western countries. In this type, tumor cells are positive for CD3 and CD30 on immunohistochemistry staining, but negative for CD8 and CD56. On the other hand, EATL type II has been renamed MEITL, shows no definite association with celiac disease, and occurs in an Asian population. In this type of malignancy, tumor cells are positive for CD3, CD8 and CD56, but negative for CD30[3,4]. MEITL is most frequently found in the jejunum and ileum[5,6], and often presents with gastrointestinal perforation or obstruction[2]. MEITL is known to have a very poor prognosis due to treatment resistance and perforation or obstruction of the bowel at diagnosis or during the course of treatment[7]. Herein, we present a case of MEITL that was diagnosed following upper gastrointestinal bleeding from an ulcerative duodenal lesion, and who enjoyed recurrence-free survival for 5 years following treatment.

A 68-year-old female presented to the emergency department with melena.

The melena started a day before she consulted us. She had no past history of chronic abdominal symptoms suggesting the presence of celiac disease.

The patient had a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

She had no significant personal and family history.

Her body temperature was 36.4 ºC, blood pressure was 128/85 mmHg, and heart rate was 98 bpm with sinus rhythm. She had mild abdominal tenderness, but there was no obvious hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy. Digital rectal examination revealed melena.

Laboratory tests indicated a hemoglobin level of 11.3 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen level of 26.0 mg/dL, and creatinine level of 1.64 mg/dL. Her serum lactate dehydrogenase level was 232 U/L (106- 211 U/L) and soluble interleukin-2 receptor level was 213 U/mL (145- 519 U/mL) (Table 1).

| Items | Data | Reference | Items | Data | Reference | Items | Data | Reference |

| WBC | 6720 /μL | 3500-9100 | TP | 7.5 g/dL | 6.4-8.4 | γ-GTP | 12 U/L | 16-73 |

| RBC | 393 × 104 /μL | 376-500 | Alb | 4.5 g/dL | 3.6-5.2 | Na | 140 mEq/L | 135-146 |

| Hb | 11.3 g/dL | 11.3-15.2 | BUN | 26.0 mg/dL | 6-22 | Cl | 107 mEq/L | 96-108 |

| Hct | 34.2% | 33.4-44.9 | Cre | 0.81 mg/dL | 0.40-0.80 | K | 4.4 mEq/L | 3.5-5.0 |

| MCV | 87.0 fL | 79-100 | T-bil | 0.5 mg/dL | 0.2-1.2 | CRP | 0.08 mg/dL | 0-0.23 |

| MCHC | 33.0% | 13.0-36.9 | CK | 140 U/L | 43-165 | sIL-2R | 213 U/mL | 145-519 |

| Plt | 21.4 × 104 /μL | 13.0-16.9 | AST | 31 U/L | 13-33 | HBs Ag | (-) | (-) |

| PT | 68% | 70-130 | ALT | 12 U/L | 6-30 | HCV Ab | (-) | (-) |

| APTT | 38.5 s | 24-39 | LDH | 232 U/L | 106-211 | HTLV-1 Ab | (-) | (-) |

| ALP | 220 U/L | 100-340 |

Urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed an ulcerative lesion with fresh blood clots in the transverse part of the duodenum (Figure 1A). Based on the location and shape of the lesion, we suspected not only a peptic ulcer, but also an ulcer caused by vascular malformation or malignancy. Therefore, we decided to interrupt the endoscopy and perform contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed slight localized contrast enhancement on the wall of the transverse part of the duodenum in the early phase of contrast injection (Figure 1B). No vascular lesions were observed, and there was no extravasation of contrast agent in the delayed phase. EGD was immediately resumed again for further observation of the lesion. When we removed the blood clots, a protruding vessel was seen at the base of the ulcer, which was coagulated using hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1C).

Following this hemostatic treatment, the patient was discharged from the hospital without re-bleeding. The lesion that caused the bleeding was suspected to be a malignant tumor of the duodenum based on its location. EGDs, including forceps biopsies from the ulcerative lesion, were performed three times after the initial hemostatic treatment. While the first and second biopsies revealed no malignancy, the third biopsy showed findings suggestive of malignant lymphoma. On pathological evaluation, diffuse proliferation of atypical medium-sized lymphoid cells was seen in the entire mucosa, along with a few intraepithelial lesions (Figure 2A and B). No necrosis was observed. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the cells were positive for CD3 and CD56, and negative for CD4, CD5, CD8, CD20 and EBER (Figure 2C-E).

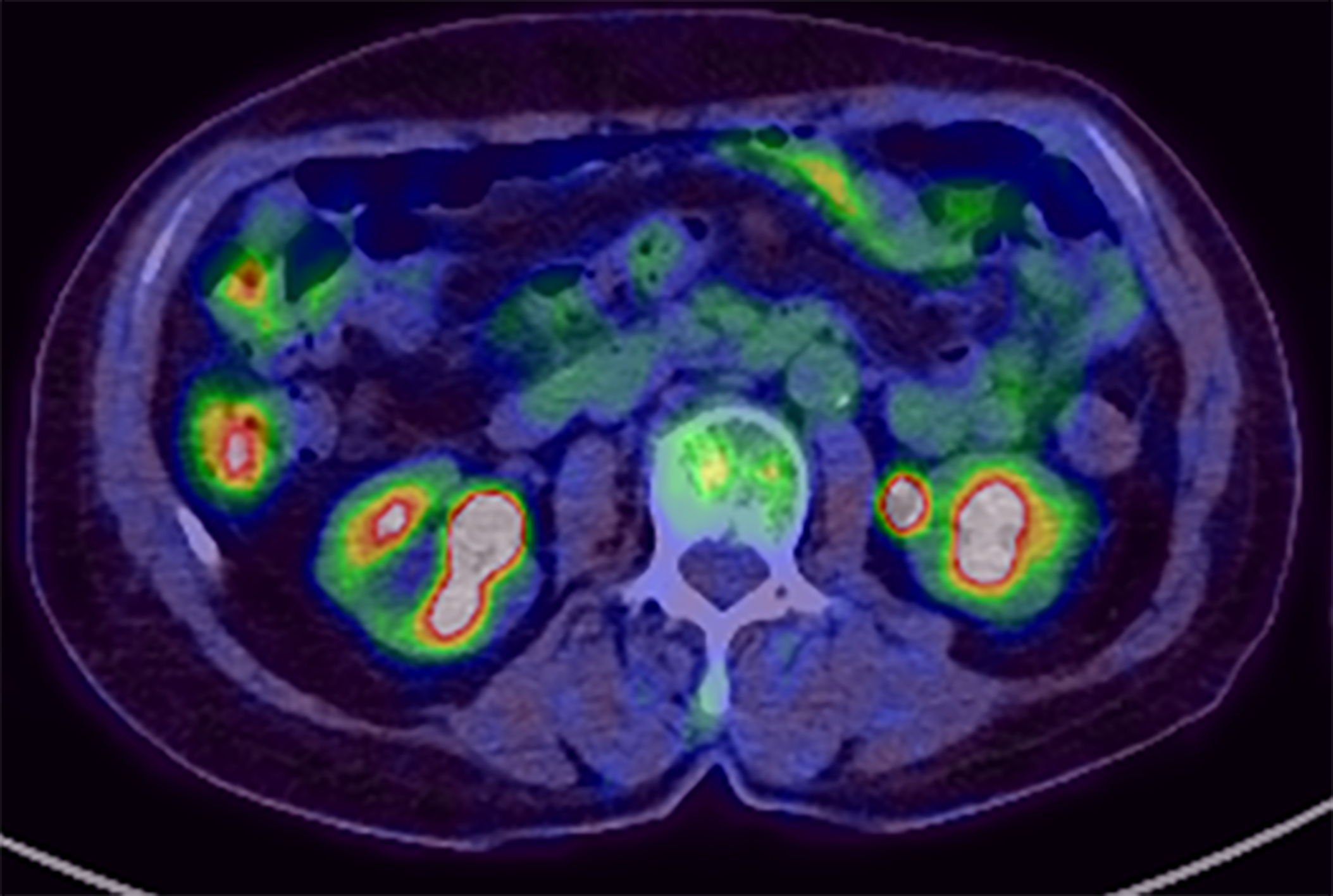

At this point, MEITL was suspected, and examinations for systemic lesions were subsequently performed. No abnormal lymphocytes were found on iliac bone marrow examination. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron emission tomography/CT (18FDG-PET/CT) showed nodular FDG accumulation in the wall of the transverse part of the duodenum, consistent with the findings of contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 3). There was no abnormal FDG accumulation in the systemic lymph nodes or other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. The results of total colonoscopy and random biopsies of the gastrointestinal tract were unremarkable.

Pathological evaluations of the duodenal biopsy samples were performed by expert pathologists. The results of immunostaining of the duodenal biopsy specimen were consistent with MEITL.

Based on the clinical course, features of the tumor and imaging evaluations, we diagnosed MEITL (previously EATL type II) confined to the duodenum.

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) chemotherapy was administered without a dosage reduction.

EGD performed after three cycles of CHOP therapy clearly showed that the ulcerative lesion in the duodenum had reduced in size (Figure 4A), and no atypical lymphoid cells were detected in biopsy specimens taken from the lesion. The patient tolerated the chemotherapy well and received eight full cycles of CHOP chemotherapy. 18FDG-PET/CT after the final cycle revealed no abnormal FDG accumulation in the transverse part of the duodenum. Therefore, we concluded that the patient had achieved complete remission (CR). EGD at the last follow-up examination revealed a scarred ulcer (Figure 4B), and 18FDG-PET/CT showed no abnormal FDG accumulation (Figure 5). The patient has been in CR for 68 mo after the initial diagnosis.

Our experience in this case highlights two important clinical points. First, MEITL can present as gastrointestinal bleeding, and not just as intestinal perforation and obstruction. Second, patients with MEITL can survive for a long time if effective treatment is administered early.

MEITL is a primary intestinal T-cell lymphoma previously known as EATL type II[1]. It is a rare intestinal tumor, accounting for 1.7% of all malignant lymphomas[8] and less than 10%-16% of gastrointestinal lymphomas[9]. MEITL differs from EATL (previously EATL type I) in that it predominantly affects Asian populations and is not associated with celiac disease[10]. Histologically, it consists of monomorphic small- to medium-sized cells that usually express CD3, CD8 and CD56, but not CD30[3,4]. Positive rates for CD8 and CD56 were reported to be 63-79% and 73-95%, respectively[8,11]. The present case had no past history of chronic abdominal symptoms suggestive of the presence of celiac disease. Histopathological examination revealed an infiltration of atypical medium-sized lymphoid cells in the entire mucosa, along with intraepithelial lesions, and immunostaining was positive for CD3 and CD56 and negative for CD5 and CD8, leading to the diagnosis of MEITL.

Our MEITL patient presented with gastrointestinal bleeding and not intestinal perforation or obstruction. More than 50% of MEITL cases are diagnosed as a result of intestinal perforation or obstruction, and emergency surgery is required in about 40% of them[9,12]. In contrast, MEITL is less frequently detected as a result of gastro

| Case | Ref. | Age/Sex | Symptom | Location | Macroscopic finding | Perforation | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | [13] | 76/M | Gastrointestinal bleeding | Jejunum | Ulcer | Yes | EATL | Operation → chemotherapy | 24 mo/alive |

| 2 | [14] | 77/M | Positive for fecal occult bleeding | Jejunum | Ulcer, stenosis | No | MEITL | Operation | NA |

| 3 | [15] | 68/M | Melena | Stomach | Ulcer (type 3 tumor) | No | MEITL | Chemotherapy | 13 mo/death |

| 4 | [16] | 65/M | Gastrointestinal bleeding | Stomach | NA | No | MEITL | Chemotherapy | 13 mo/death |

| 5 | Our case | 68/F | Melena | Duodenum | Ulcer | No | MEITL | Chemotherapy | 66 mo/alive |

In a histopathological study of a case of MEITL with perforation, tumor cells positive for TIA-1 or Granzyme B, a cytotoxic molecule, were reported to have markedly infiltrated all layers of the intestinal wall[18,19]. This suggests that MEITL easily penetrates the gastrointestinal tract by growing destructively through all its layers, resulting in a relatively lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Our case suggests that patients with MEITL might survive for a long time if effective treatment is administered at an early stage. MEITL is an aggressive T-cell lymphoma with a very poor prognosis and high mortality rate[20]. The median overall survival was previously reported as 7 mo[11,17], and the 5-year survival rate was reported as 20%, with a 5-year failure-free survival rate of 4%[8]. Surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are all used to treat MEITL, although these treatments have shown poor overall outcomes[21]. Although several studies have demonstrated the benefit of autologous stem cell transplantation[22-25], there is no standardized treatment strategy. Moreover, MEITL often requires emergency surgery due to intestinal perforation or obstruction, and the lesion has usually spread before it is diagnosed[26]. Unfortunately, most patients are unable to receive effective chemotherapy due to their poor performance status and severe malnutrition at the time of diagnosis[27]. On the other hand, in a study of 26 patients with MEITL, the prognosis of non-perforated cases was significantly better than that of perforated cases, suggesting that early treatment before perforation might improve the prognosis of MEITL[28]. The present case has shown the most favorable prognosis to date, because we were able to diagnose MEITL at an early stage due to her presentation with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and hence performed chemotherapy while the patient was in good general condition. In the previously reported cases shown in Table 2, as well, the prognosis tended to be relatively good in cases that were diagnosed after hemorrhage. This is probably because the lesion was perforated in only one case and the other cases were able to start chemotherapy before perforation. This suggests that gastrointestinal bleeding is an important sign that can lead to early diagnosis and treatment of MEITL.

So far, only one other case of MEITL with a failure-free survival for more than 5 years has been reported[29]. This case was diagnosed early by the finding of only chorionic changes (white villi) without a mass or ulcer, and CHOP therapy was started before perforation. Ishibashi et al[30] reported that edematous and granular mucosae with or without villous atrophy are characteristic findings of prodromal lesions of MEITL in the small intestine or duodenum. Even in the absence of obvious masses or ulcers, it is important not to overlook such micro-changes in the gastrointestinal mucosa to facilitate the early diagnosis of MEITL.

Another point to note is that the diagnostic ratio of intestinal T-cell lymphoma (ITCL) by endoscopy, including tissue biopsy, is low. Sun et al[31] reported that out of 34 ITCL patients who underwent endoscopy, eight patients (23.5%) were definitively diagnosed with ITCL by histology. Daum et al[32] also reported that only 21% of intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas were diagnosed endoscopically. In the present case as well, a total of three tissue biopsies were required before the final diagnosis of MEITL. The following are some of the reasons for this: (1) Tissue specimens from endoscopic biopsy are usually not sufficiently large to allow correct diagnosis; (2) ITCL is known to be primarily located in the submucosa and smooth muscle, and it is difficult to detect the lesion from biopsy specimens through the mucosal layer; and (3) The disease is easy to overlook because of its rarity. Hence, a tissue biopsy of ulcerative gastrointestinal lesions should be performed carefully from the base of the ulcer, while considering the possibility of malignant lymphoma.

We report a case of MEITL diagnosed after upper gastrointestinal bleeding from an ulcerative duodenal lesion, with recurrence-free survival for 5 years after chemotherapy. MEITL can present as gastrointestinal bleeding, and not only as intestinal perforation and obstruction. In addition, although MEITL is an aggressive T-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis, patients with MEITL can survive for a long time if effective treatment is administered early. Therefore, it is important to carefully perform histological examination to rule out MEITL when bleeding from a duodenal ulcer is observed.

We thank Dr. Ayako Gamachi (Chief of the Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Almeida Memorial Hospital) for providing histopathological images of the duodenal biopsy.

| 1. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5635] [Article Influence: 563.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | van de Water JM, Cillessen SA, Visser OJ, Verbeek WH, Meijer CJ, Mulder CJ. Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma and its precursor lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:43-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Vliet C, Spagnolo DV. T- and NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: review and update. Pathology. 2020;52:128-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takeshita M, Nakamura S, Kikuma K, Nakayama Y, Nimura S, Yao T, Urabe S, Ogawara S, Yonemasu H, Matsushita Y, Karube K, Iwashita A. Pathological and immunohistological findings and genetic aberrations of intestinal enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma in Japan. Histopathology. 2011;58:395-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferreri AJ, Zinzani PL, Govi S, Pileri SA. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu Z, He L, Jiao Y, Wang H, Suo J. Type II enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma in the duodenum: A rare case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nijeboer P, Malamut G, Mulder CJ, Cerf-Bensussan N, Sibon D, Bouma G, Cellier C, Hermine O, Visser O. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: improving treatment strategies. Dig Dis. 2015;33:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Delabie J, Holte H, Vose JM, Ullrich F, Jaffe ES, Savage KJ, Connors JM, Rimsza L, Harris NL, Müller-Hermelink K, Rüdiger T, Coiffier B, Gascoyne RD, Berger F, Tobinai K, Au WY, Liang R, Montserrat E, Hochberg EP, Pileri S, Federico M, Nathwani B, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: clinical and histological findings from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood. 2011;118:148-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tse E, Gill H, Loong F, Kim SJ, Ng SB, Tang T, Ko YH, Chng WJ, Lim ST, Kim WS, Kwong YL. Type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Afzal A, Esmaeili A, Ibrahimi S, Farooque U, Gehrs B. Monomorphic Epitheliotropic Intestinal T-Cell Lymphoma With Extraintestinal Areas of Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Involvement. Cureus. 2020;12:e10021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yi JH, Lee GW, Do YR, Jung HR, Hong JY, Yoon DH, Suh C, Choi YS, Yi SY, Sohn BS, Kim BS, Oh SY, Park J, Jo JC, Lee SS, Oh YH, Kim SJ, Kim WS. Multicenter retrospective analysis of the clinicopathologic features of monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2019;98:2541-2550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zettl A, deLeeuw R, Haralambieva E, Mueller-Hermelink HK. Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:701-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kinaci E, Gunes ME, Huq GE. An unusual presentation of EATL type 1: Emergency surgery due to life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:961-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ho HC, Nagar AB, Hass DJ. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and video capsule retention due to enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:536-538. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lu S, Zhou G, Chen M, Liu W, Zhao S. Monomorphic Epitheliotropic Intestinal T-cell Lymphoma of the Stomach: Two Case Reports and a Literature Review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:410-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chan TSY, Lee E, Khong PL, Tse EWC, Kwong YL. Positron emission tomography computed tomography features of monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma. Hematology. 2018;23:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Olmos-Alpiste F, Vázquez I, Gallardo F, Sánchez-Gonzalez B, Colomo L, Pujol RM. Monomorphic Epitheliotropic Intestinal T-Cell Lymphoma With Secondary Cutaneous Involvement: A Diagnostic Challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43:300-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamura K, Ishigure K, Ishida N. [Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma triggering perforated peritonitis successfully treated with comprehensive therapy]. J Ipn Surg Assoc. 2011;72:821-827. |

| 19. | Abouyabis AN, Shenoy PJ, Lechowicz MJ, Flowers CR. Incidence and outcomes of the peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:2099-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tan SY, Chuang SS, Tang T, Tan L, Ko YH, Chuah KL, Ng SB, Chng WJ, Gatter K, Loong F, Liu YH, Hosking P, Cheah PL, Teh BT, Tay K, Koh M, Lim ST. Type II EATL (epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma): a neoplasm of intra-epithelial T-cells with predominant CD8αα phenotype. Leukemia. 2013;27:1688-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gentille C, Qin Q, Barbieri A, Ravi PS, Iyer S. Use of PEG-asparaginase in monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma, a disease with diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ikebe T, Miyazaki Y, Abe Y, Urakami K, Ohtsuka E, Saburi Y, Saburi M, Ando T, Kohno K, Ogata M, Kadota J. Successful treatment of refractory enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma using high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Intern Med. 2010;49:2157-2161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sieniawski M, Angamuthu N, Boyd K, Chasty R, Davies J, Forsyth P, Jack F, Lyons S, Mounter P, Revell P, Proctor SJ, Lennard AL. Evaluation of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma comparing standard therapies with a novel regimen including autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3664-3670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jantunen E, Boumendil A, Finel H, Luan JJ, Johnson P, Rambaldi A, Haynes A, Duchosal MA, Bethge W, Biron P, Carlson K, Craddock C, Rudin C, Finke J, Salles G, Kroschinsky F, Sureda A, Dreger P; Lymphoma Working Party of the EBMT. Autologous stem cell transplantation for enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a retrospective study by the EBMT. Blood. 2013;121:2529-2532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nijeboer P, de Baaij LR, Visser O, Witte BI, Cillessen SA, Mulder CJ, Bouma G. Treatment response in enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma; survival in a large multicenter cohort. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chandesris MO, Malamut G, Verkarre V, Meresse B, Macintyre E, Delarue R, Rubio MT, Suarez F, Deau-Fischer B, Cerf-Bensussan N, Brousse N, Cellier C, Hermine O. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a review on clinical presentation, diagnosis, therapeutic strategies and perspectives. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:590-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gale J, Simmonds PD, Mead GM, Sweetenham JW, Wright DH. Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment of 31 patients in a single center. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:795-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kikuma K, Yamada K, Nakamura S, Ogami A, Nimura S, Hirahashi M, Yonemasu H, Urabe S, Naito S, Matsuki Y, Sadahira Y, Takeshita M. Detailed clinicopathological characteristics and possible lymphomagenesis of type II intestinal enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in Japan. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1276-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kakugawa Y, Terasaka S, Watanabe T, Tanaka S, Taniguchi H, Saito Y. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in small intestine detected by capsule endoscopy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1623-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Ishibashi H, Nimura S, Kayashima Y, Takamatsu Y, Aoyagi K, Harada N, Kadowaki M, Kamio T, Sakisaka S, Takeshita M. Multiple lesions of gastrointestinal tract invasion by monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma, accompanied by duodenal and intestinal enteropathy-like lesions and microscopic lymphocytic proctocolitis: a case series. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sun ZH, Zhou HM, Song GX, Zhou ZX, Bai L. Intestinal T-cell lymphomas: a retrospective analysis of 68 cases in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Daum S, Ullrich R, Heise W, Dederke B, Foss HD, Stein H, Thiel E, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Intestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter prospective clinical study from the German Study Group on Intestinal non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2740-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Strainiene S S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX