Published online Sep 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i34.5625

Peer-review started: May 3, 2021

First decision: June 2, 2021

Revised: June 11, 2021

Accepted: August 17, 2021

Article in press: August 17, 2021

Published online: September 14, 2021

Processing time: 129 Days and 5.1 Hours

The serrated pathway accounts for 30%-35% of colorectal cancer (CRC). Unlike hyperplastic polyps, both sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) and traditional serrated adenomas are premalignant lesions, yet SSLs are considered to be the principal serrated precursor of CRCs. Serrated lesions represent a challenge in detection, classification, and removal–contributing to post-colonoscopy cancer. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to characterize these lesions properly to ensure complete removal. A retrospective cohort study developed a diagnostic scoring system for SSLs to facilitate their detection endoscopically and subsequent removal. From the study, it can be ascertained that both indistinct border and mucus cap are essential in both recognizing and diagnosing serrated lesions. The proximal colon poses technical challenges for some endoscopists, which is why high-quality colonoscopy plays such an important role. The indistinct border of some SSLs poses another challenge due to difficult complete resection. Overall, it is imperative that gastroenterologists use the key features of mucus cap, indistinct borders, and size of at least five millimeters along with a high-quality colo

Core Tip: Serrated lesions represent a challenge in detection, classification, and removal. The mucus cap, flat nature, and indistinct borders make these lesions difficult to localize endoscopically. Therefore, it is important to characterize these lesions properly to ensure complete removal and a reduction in post-colonoscopy cancer. A study recently developed a diagnostic scoring system for sessile serrated lesions to facilitate their detection endoscopically and removal. The study shows that both indistinct border and mucus cap are essential in both recognizing and diagnosing serrated lesions, further emphasizing the importance of a good colon preparation and a high-quality colonoscopy.

- Citation: Trovato A, Turshudzhyan A, Tadros M. Serrated lesions: A challenging enemy. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(34): 5625-5629

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i34/5625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i34.5625

The serrated pathway accounts for 30%-35% of colorectal cancer (CRC)[1]. Serrated lesions are characterized histologically by a saw-tooth or serrated glandular pattern, likely secondary to a lack of apoptosis of dividing cells in the colonic crypts, resulting in the cells folding onto each other and giving it a serrated appearance. While a variety of molecular mechanisms contribute to neoplastic progression, hypermethylation of DNA promoter regions resulting in a CpG island methylator phenotype is believed to be the major mechanism driving the serrated pathway to CRC[2] . According to the 2019 World Health Organization 5th edition classification, serrated colorectal lesions can be further defined into four main categories: Hyperplastic polyps (HPs), with microvesicular (MVHP) and goblet cell-rich subtypes; sessile serrated lesion (SSL) and SSL with dysplasia, both previously known as SSA/Ps with or without cytological dysplasia; traditional serrated adenoma (TSA); and serrated adenoma, unclassified[3]. HPs are the most common non-neoplastic polyps in the colon, typically located in the rectosigmoid region and are often less than five millimeters in size. These polyps are polypoid in appearance and do not exhibit dysplasia and therefore do not increase the risk of CRC[4]. SSLs are usually more prevalent in the proximal colon and have a smooth surface with a "cloud-like" appearance[2]. They can be flat or sessile, and may be covered in mucus. TSAs can be pedunculated or sessile in appearance and are typically found in the rectosigmoid colon. Unlike HPs, both SSLs and TSAs are premalignant lesions, yet SSLs are considered to be the principal serrated precursor of CRCs[5]. Therefore, SSLs must be distinguished from HPs to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

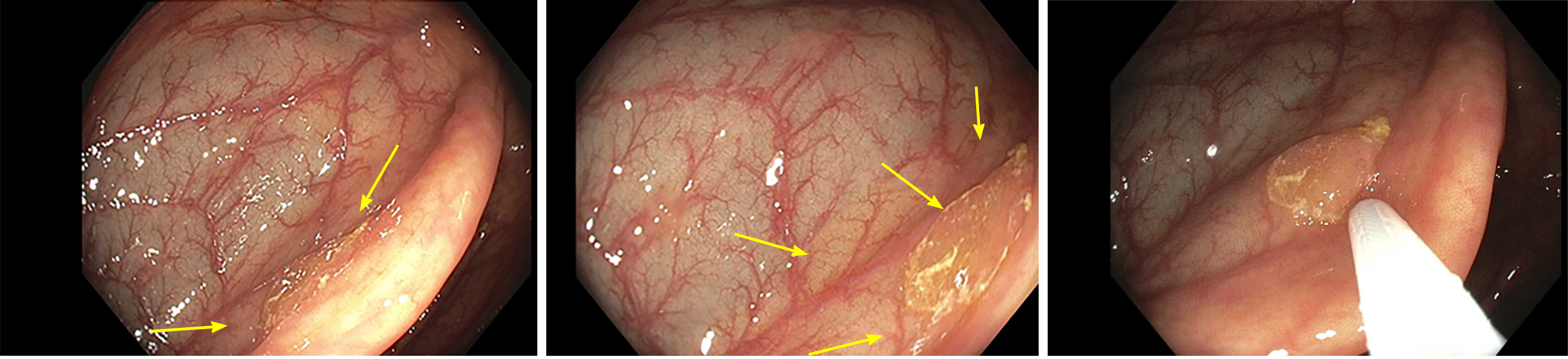

Serrated lesions represent a challenge in detection, classification, and removal. As portrayed in Figure 1, the mucus cap, flat nature, and indistinct borders makes these lesions difficult to localize endoscopically, resulting in them being incompletely removed or easily missed[6]. In terms of classification, SSLs may initially be misclassified as HPs due to similarities in histological appearance. Serrated lesions may exhibit MVHP pathology in some areas, but display SSL morphology, blurring the lines between SSLs and HPs and resulting in a misclassification and misdiagnosis[5]. In fact, certain factors such as location in the proximal colon as well as size greater than five millimeters have been shown to change the pathological diagnosis of HP to SSL[7]. For all of these reasons combined with the fact that they tend to exhibit a more rapid progression to cancer, SSLs play a role in post-colonoscopy cancer[6]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to characterize these lesions properly to ensure complete removal and a reduction in post-colonoscopy cancer. Nishizawa et al[8] 2021 performed a retrospective cohort study to develop a diagnostic scoring system for SSLs to facilitate their detection endoscopically and subsequent removal.

Nishizawa et al[8] 2021 collected data on serrated lesions diagnosed either by endoscopic or pathologic means. They analyzed 232 polyps that were diagnosed as serrated polyps, and univariate analysis determined that the proximal colon location (P = 0.003), size greater than five millimeters (P < 0.001), presence of mucus cap (P < 0.001), presence of cloud-like surface (P < 0.001), and presence of microvascular vessels (P = 0.024) were significantly associated with the presence of SSLs. Through multivariate analysis, mucus cap (P = 0.005), size greater than five millimeters (P = 0.033), and indistinct borders (P = 0.033) were deemed as characteristics independently associated with the diagnosis of SSLs. Each of these characteristics were assigned one point, the sum of them defining the endoscopic SSL diagnosis score. Through receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis, a cut-off score of three was determined to be most optimal, resulting in prediction of pathological SSLs with a 75% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and 78.4% accuracy. Overall, the authors determined that serrated polyps with a size greater than five millimeters, presence of a mucus cap, and indistinct borders should be removed during colonoscopy[8].

From the study, it can be ascertained that both indistinct border and mucus cap are essential in recognizing and diagnosing serrated lesions. The mucus cap can mimic the appearance of a benign mucus collection and thus be missed by the untrained eye easily on colonoscopy. A practical word of advice would be to wash the mucus gently starting at the edge to observe if there is polyp tissue hiding underneath. This further emphasizes the importance of a good colon preparation and a high-quality colonoscopy. Bowel preparation should be adequate to consistently allow for detection of polyps greater than five millimeters after leftover stool suctioning[9]. It is important to note that chyme from the small intestine can coat the proximal colon when bowel preparation agents are given the day prior to the procedure, resulting in impaired detection of flat lesions[10]. Furthermore, as the time interval between the end of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy increases by the hour, the likelihood of having a good or excellent bowel preparation of the cecum is decreased by ten percent[11]. Splitting of bowel cleansing to half of the preparation given on the day of the procedure has shown to have overwhelmingly superior efficacy when compared to traditional regimen[12]. Split dose leads to higher adenoma detection rate and several guidelines have endorsed its use[13,14].

The proximal colon poses technical challenges for some endoscopists, which is why high-quality colonoscopy plays such an important role. Both retroflexion and second-look techniques have been shown to improve adenoma detection rate in the right colon[15,16]. Retroflexion in the right colon is a maneuver in which the colonoscope makes a U-turn, allowing better visualization of the proximal sides of the haustral folds[17]. A 2017 meta-analysis found that retroflexion detected 17% of adenomas of the right colon that would have otherwise been missed on conventional colonoscopy[15]. Superiority of retroflexion to the second examination has not been confirmed. Second examination of the right colon has been shown to improve adenoma detection rate by a very similar amount and may be preferred over retroflexion as it is an easier maneuver to perform[16].

The indistinct border of some SSLs poses another challenge due to difficulty of complete resection. For instance, studies have suggested that residual tissue determined to be complete after polypectomy ranges from 6.5%-22.7%[18]. A pooled analysis from eight surveillance studies that followed patients with adenoma post-colonoscopy suggested that roughly 20% of malignancies were due to incomplete resection while nearly 50% of post-colonoscopy malignancies were acquired from missed lesions[19]. It is recommended that the type of resection method (e.g., cold snare, hot snare, EMR) is thoroughly documented. It is also recommended that, if resected en block, non-pedunculated lesions are to be pinned to a flat surface prior to being submitted to pathology and be measured for the depth of the submucosal invasion[10].

The key constituents of the diagnostic score proposed by Nishizawa et al[8] 2021 provide essential information about the nature of the serrated lesions. It is imperative that gastroenterologists use those key features along with a high-quality colonoscopy and a good bowel preparation to improve the SSL detection rate. The article also stresses the importance of complete resection of the SSL and training of endoscopists to recognize and fully resect such challenging lesions.

| 1. | Singh R, Zorrón Cheng Tao Pu L, Koay D, Burt A. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: Where are we at in 2016? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7754-7759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Higuchi T, Sugihara K, Jass JR. Demographic and pathological characteristics of serrated polyps of colorectum. Histopathology. 2005;47:32-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2747] [Article Influence: 457.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Laiyemo AO, Murphy G, Sansbury LB, Wang Z, Albert PS, Marcus PM, Schoen RE, Cross AJ, Schatzkin A, Lanza E. Hyperplastic polyps and the risk of adenoma recurrence in the polyp prevention trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, Goldblum JR, Guillem JG, Kahi CJ, Kalady MF, O'Brien MJ, Odze RD, Ogino S, Parry S, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Wise PE, Young J, Church J. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315-29; quiz 1314, 1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 825] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 6. | Iwatate M, Kitagawa T, Katayama Y, Tokutomi N, Ban S, Hattori S, Hasuike N, Sano W, Sano Y, Tamano M. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer rate in the era of high-definition colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7609-7617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Niv Y. Changing pathological diagnosis from hyperplastic polyp to sessile serrated adenoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1327-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nishizawa T, Yoshida S, Toyoshima A, Yamada T, Sakaguchi Y, Irako T, Ebinuma H, Kanai T, Koike K, Toyoshima O. Endoscopic diagnosis for colorectal sessile serrated lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:1321-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Robertson DJ, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Rex DK. Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:463-485.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:903-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, Cryer B, Davila R, Cipher D, Harford WV. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:700-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cohen LB. Split dosing of bowel preparations for colonoscopy: an analysis of its efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jover R, Zapater P, Polanía E, Bujanda L, Lanas A, Hermo JA, Cubiella J, Ono A, González-Méndez Y, Peris A, Pellisé M, Seoane A, Herreros-de-Tejada A, Ponce M, Marín-Gabriel JC, Chaparro M, Cacho G, Fernández-Díez S, Arenas J, Sopeña F, de-Castro L, Vega-Villaamil P, Rodríguez-Soler M, Carballo F, Salas D, Morillas JD, Andreu M, Quintero E, Castells A; COLONPREV study investigators. Modifiable endoscopic factors that influence the adenoma detection rate in colorectal cancer screening colonoscopies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:381-389.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cohen J, Grunwald D, Grossberg LB, Sawhney MS. The Effect of Right Colon Retroflexion on Adenoma Detection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Núñez Rodríguez MH, Díez Redondo P, Riu Pons F, Cimavilla M, Hernández L, Loza A, Pérez-Miranda M. Proximal retroflexion vs second forward view of the right colon during screening colonoscopy: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:725-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rex DK, Vemulapalli KC. Retroflexion in colonoscopy: why? Gastroenterology. 2013;144:882-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pohl H, Srivastava A, Bensen SP, Anderson P, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Levy LC, Toor A, Mackenzie TA, Rosch T, Robertson DJ. Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:74-80.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Robertson DJ, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Schatzkin A, Cross AJ, Zauber AG, Church TR, Lance P, Greenberg ER, Martínez ME. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014;63:949-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Teramoto-Matsubara OT S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX