Published online Jun 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i22.3097

Peer-review started: February 17, 2021

First decision: March 28, 2021

Revised: March 30, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2021

Article in press: April 20, 2021

Published online: June 14, 2021

Processing time: 111 Days and 0.3 Hours

Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis (IMP) is a rare disease, and its etiology and risk factors remain uncertain.

To investigate the possible influence of Chinese herbal liquid containing geniposide on IMP.

The detailed formula of herbal liquid prescriptions of all patients was studied, and the herbal ingredients were compared to identify the toxic agent as a possible etiological factor. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and colonoscopy images were reviewed to determine the extent and severity of mesenteric phlebosclerosis and the presence of findings regarding colitis. The disease CT score was determined by the distribution of mesenteric vein calcification and colon wall thickening on CT images. The drinking index of medicinal liquor was calculated from the daily quantity and drinking years of Chinese medicinal liquor. Subsequently, Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the correlation between the drinking index and the CT disease score.

The mean age of the 8 enrolled patients was 75.7 years and male predominance was found (all 8 patients were men). The patients had histories of 5-40 years of oral Chinese herbal liquids containing geniposide and exhibited typical imaging characteristics (e.g., threadlike calcifications along the colonic and mesenteric vessels or associated with a thickened colonic wall in CT images). Calcifications were confined to the right-side mesenteric vein in 6 of the 8 patients (75%) and involved the left-side mesenteric vein of 2 cases (25%) and the calcifications extended to the mesorectum in 1 of them. The thickening of colon wall mainly occurred in the right colon and the transverse colon. The median disease CT score was 4.88 (n = 7) and the median drinking index was 5680 (n = 7). After Spearman’s correlation analysis, the median CT score of the disease showed a significant positive correlation with the median drinking index (r = 0.842, P < 0.05).

Long-term oral intake of Chinese herbal liquid containing geniposide may play a role in the pathogenesis of IMP.

Core Tip: Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis (IMP) is a rare entity that appears almost exclusively in Asian populations and is characterized by calcification of the mesenteric veins and thickening of the wall of the right hemicolon. Long-term and frequent ingestion of biochemicals and toxins are thought to be associated with the disease. Herbal ingredients present in the patients were compared to identify the toxic agent as a possible etiological factor, and the positive correlation of the computed tomography disease score and drinking index was explored. Furthermore, underlying disease (e.g., diabetes, chronic nephritis, or malignancy) may be risk factors for IMP.

- Citation: Wen Y, Chen YW, Meng AH, Zhao M, Fang SH, Ma YQ. Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with long-term oral intake of geniposide. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(22): 3097-3108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i22/3097.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i22.3097

Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis (IMP) is a rare form of ischemic colitis that usually affects the right hemicolon. It is almost exclusively observed in Asian populations, is characterized by calcification of mesenteric veins and thickening of the wall of the right hemicolon. The etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear, but it is thought that long-term and frequent ingestion of biochemicals and toxins are associated with the disease[1,2]. As clarified by existing studies, long-term intake of herbal medicines or medicinal liquor containing geniposide is recognized as one of the major causes of IMP[2,3]. In this study, we describe 8 patients with mesenteric phlebosclerosis with long-term exposure to Chinese herbal medicines or medicinal liquor. The clinical manifestations and imaging features were summarized, and the relationship between the alcohol index and the severity of IMP observed by computed tomography (CT) were analyzed. This is an interesting article on a relatively rare disease and may present insights into the etiology of IMP.

This was a retrospective study, and the data originated from the medical records at Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital from June 2016 to December 2020. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital. Informed consent was waived; patient confidentiality was protected.

The medical records of patients meeting the following inclusion criteria were retrospectively reviewed: (1) The clinical diagnosis of IMP was confirmed by abdominal CT, endoscopy, or pathology including at least one complete abdominal CT examination with or without intravenous contrast medium injection; and (2) Patients had complete clinical information.

Eight patients were identified and their clinical data, including symptoms, anamnesis, history of herbal medicines, and therapy, were collected. Patient herbal medicine history, herbal medicine names, contact time, and daily intake were highlighted. Of note, 7 patients consumed similar dosages of two medicines, Wu chia-pee liquor and Wanying die-da wine for a long time. Moreover, the degree of the two wines was similar. The drinking index was calculated as the daily intake (mL) × drinking duration (years).

Gastroscopy was performed with an Olympus 290 colonoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The endoscope was inserted to 5-10 cm from the terminal ileum. The color of mucosa, the vascular textures of the terminal ileum, ileocecal area, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum were noted, and the presence of congestion, edema, erosion and ulcer were verified. Multiple samples of the intestinal mucosa were collected for histopathological examination.

CT scans were generated with a 64-channel multi-detector CT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). The CT scanning parameters were: Detector collimation, 1 mm; pitch, 1.5:1; tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current, 120-250 mAs; rotation time, 0.33 s. Contrast-enhanced CT was performed with 80-90 mL of 370 mg I/mL iodinated contrast agent (Ultravist, Bayer Schering Pharma AG) injected in a peripheral vein with a dual high-pressure syringe at a flow rate of 2.2-3 mL/s. A bolus-tracking technique was used to obtain arterial- and venous-phase CT images with delays of 10 s and 50-65 s after a 100 Hounsfield unit threshold of the descending abdominal aorta. Image reconstruction was performed with a 1 mm slice thickness and a 1 mm slice interval with an Application Development Workstation (MM Reading, syngo.via, Version VB20A, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Forchheim, Germany).

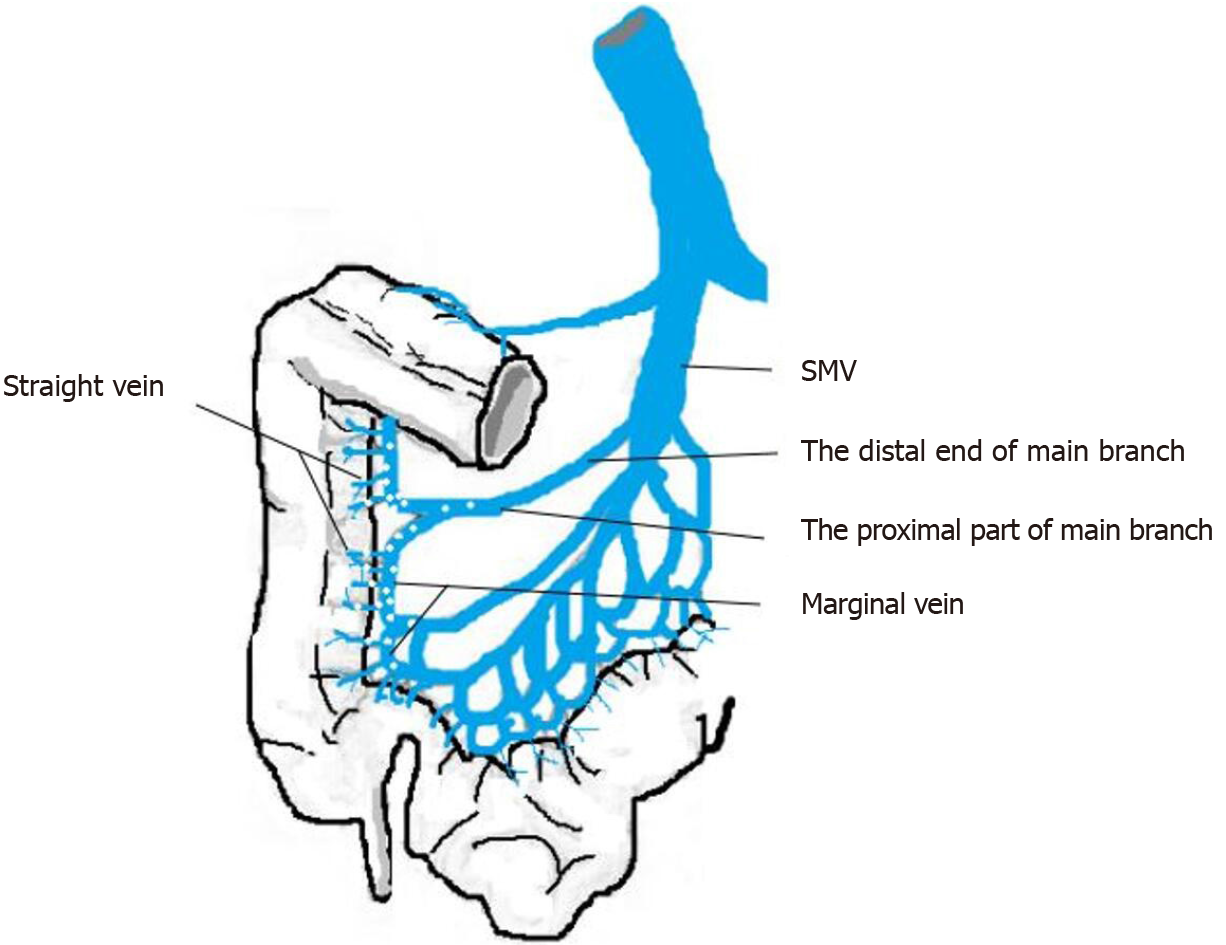

The CT imaging characteristics were assessed by 2 radiologists with 5- and 10-year of clinical experience. The severity of IMP was assessed with consideration of the calcification distribution at the tributaries of the portal vein and the range of thickening of the intestinal wall. Colonic wall thickening was defined as a lumen width exceeding 2 cm and wall thickness exceeding 5 mm. The CT scores of the IMP cases are listed in Table 1). A 4-grade calcification score was evaluated by the scope of mesenteric venous calcification of the colon[4]. Specifically, venous calcifications limited to the straight vein were scored as 1, and calcifications extending to the paracolic marginal vein were scored as 2. If the calcifications extended to the proximal part of main branch of the mesenteric vein, the score was 3. If the distal end of the main branch was involved, then the score was 4. Illustrations of calcification distribution are shown in Figure 1). The severity of colon wall thickening was classified by three scores depending on the extent of the lesion. Lesions confined to the ascending colon had a severity score of 1. Those extending to the traverse colon had a severity score of 2, and those involving the descending colon or distal segment had a severity score of 3. The calcification and colon wall thickening scores were summed to obtain the disease CT score.

| No. case | Endoscopic findings | CT findings | |||||||||

| Ileal | Ileocolic | Mucosa | Bowel wall stiffening | Bowel wall thickening | Calcification dstribution1 | Luminal narrowing | |||||

| valve | color | Extended to A-colon | Extended to T-colon | Extended to L-colon | IMV | SMV | PV | ||||

| 1 | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | + | - | - | +++ | - | - | No |

| 2 | Not involvement | Involvement | Dark blue | + | + | + | - | +++ | - | - | No |

| 3 | Not involvement | Not involvement | Mild-blue | - | + | - | - | ++ | - | - | No |

| 4 | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | + | - | - | +++ | - | - | No |

| 5 | Not involvement | Involvement | Dark purple | + | + | + | - | +++ | - | - | Yes |

| 6 | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | + | + | - | +++ | - | - | No |

| 7 | Not involvement | Involvement | Dark purple | + | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | - | No |

| 8 | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | - | No |

The statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 25.0, IBM Corp, Armonk NY, United States). Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to assess the correlation between the drinking index and the disease CT score. Two-tailed P values of < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Eight male patients with an average age of 75.7 (range of 59–88) year were included. Five presented with abdominal symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, fullness, and diarrhea), one of whom had an intestinal obstruction. All 8 patients had histories of long-term use of Chinese herbal medicines or medicinal liquors. One had used an oral liquid for the treatment of chronic rhinitis. The 7 others had used Chinese medical liquors that contained gardenia, chuan xiong, and angelia dahurica. Tables 2 and 3 show the patient clinic characteristics and the ingredients that Chinese traditional medicines had in common. The patients all received conservative treatment.

| No. case | Gender | Age | Symptom | Herb contact | Dosage of liquid medicine (mL/d) | Exposure time (yr) | Underlying disease | Treatment |

| 1 | M | 59 | Abdominal pain | Bi yuan-su oral liquid | 30 | 10 | Chronic rhinitis | Conservative |

| 2 | M | 66 | Diarrhea, positive stool occult blood | Wu chia-pee liquor | 150 | 10 | Diabetes | Conservative |

| 3 | M | 69 | Abdominal distention | Wu chia-pee liquor | 150 | 10 | None | Conservative |

| 4 | M | 79 | Positive stool occult blood | Wu chia-pee liquor | 90 | 20 | None | Conservative |

| 5 | M | 80 | Abdominal pain | Wu chia-pee liquor | 200 | 30 | Hypertension | Conservative |

| 6 | M | 82 | Abdominal pain, abdominal distention | Wu chia-pee liquor | 200 | 35 | Hypertension, hepatitis B, rheumatoid arthritis | Conservative |

| 7 | M | 83 | Dysuria | Wu chia-pee liquor | 250 | 40 | Hypertension, chronic nephritis | Conservative |

| 8 | M | 88 | Limbs numbness | Wanying die-da wine | 120 | 5 | Hypertension, prostatic cancer, arthrolithiasis | Conservative |

| Name of liquid | Ingredient 1 | Ingredient 2 | Ingredient 3 | Ingredient 4 | Ingredient 5 | Ingredient 6 | Ingredient 7 |

| Wu chia-pee liquor | Gardenia | Chuan xiong | Angelia dahurica | Cortex acanthopanacis | Clematis | Tetrandra root | Angelica sinensis |

| Wanying die-da wine | Gardenia | Chuan xiong | Angelia dahurica | Cortex acanthopanacis | Clematis | Tetrandra root | Angelica sinensis |

| Bi yuan-su oral liquid | Gardenia | Chuan xiong | Angelia dahurica | - | - | - | - |

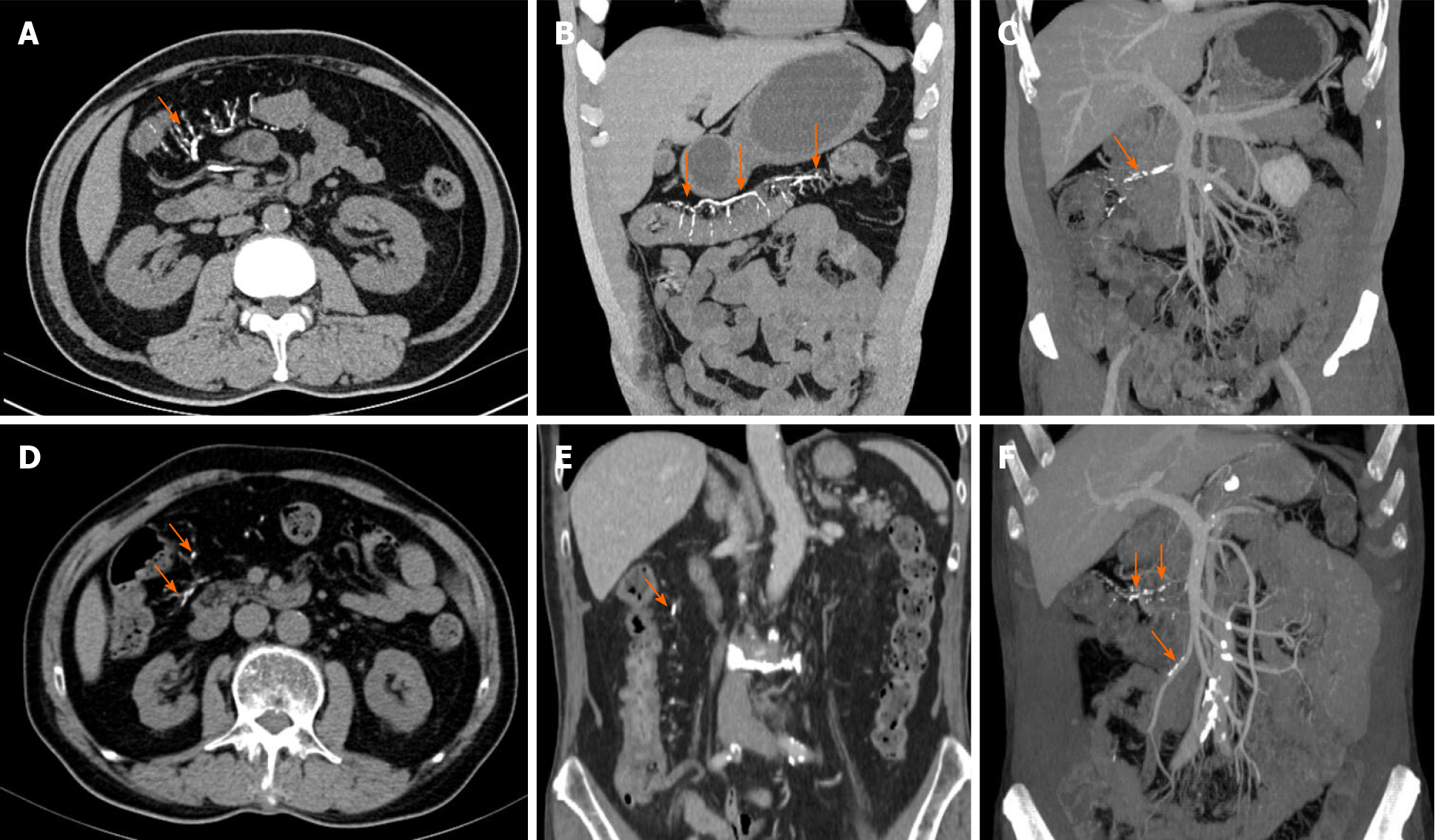

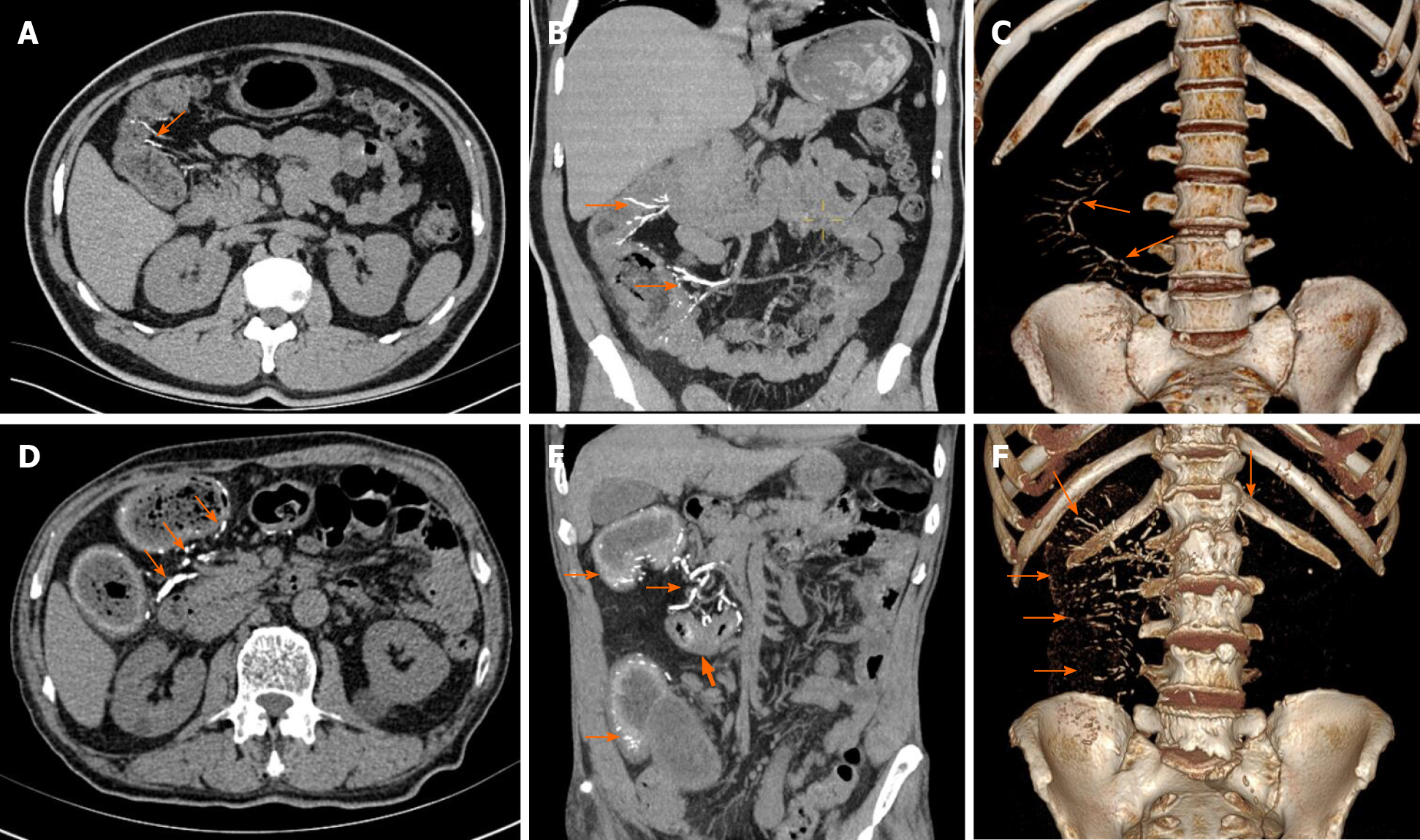

All patients presented with punctate or linear calcification on CT images. Mesenteric venous calcification involved the ascending colon of all patients and extended to the transverse colon in 4 (Figures 1 and 2). In 2 of the 8 patients, the lesions extended to the descending colon. In 1 patient, the entire colon was involved (Figure 3). Calcification was limited to the right-side mesenteric vein in 6 of the 8 cases (75%). In 2 cases (25%), the left-side mesenteric vein was involved. Diffuse wall thickening in the affected region was observed in 7 patients. One patient presented with calcification without obvious thickening of the colon wall. The wall thickening was most often seen in the right and the transverse colon.

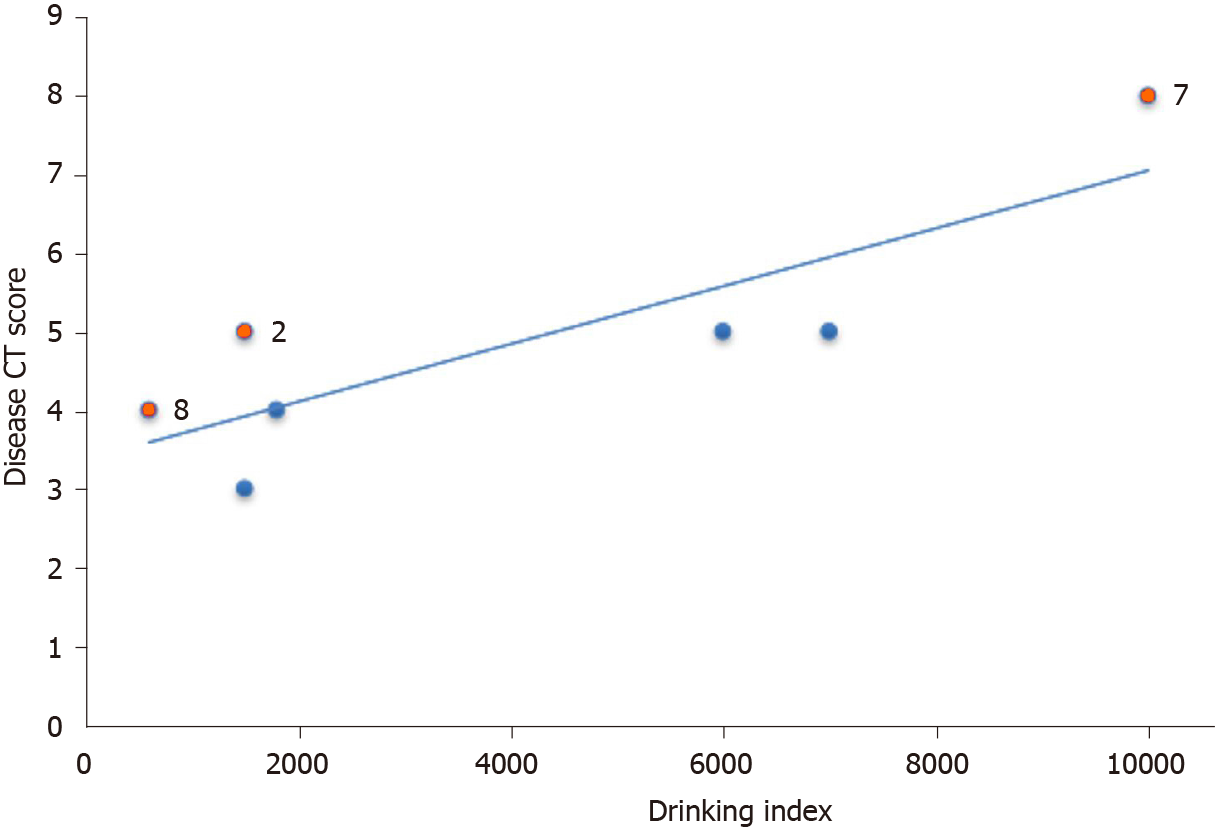

The median disease CT score was 4.88 (n = 7) and the median drinking index was 5680 (n = 7). The dispersion diagram in Figure 4 shows the relationship between the drinking index and the disease CT score. Spearman correlation analysis found a significant positive correlation between the alcohol drinking index and the disease CT score (r = 0.842, P < 0.05). In the 4 patients evaluated by of colonoscopy, blue or dark blue colored mucosa was the most characteristic variation. The colonoscopy revealed multiple erosions and ulcers in 1 patient (Figure 5). Table 1 lists the characteristic endoscopic view and CT findings. Histopathology of the biopsy samples showed the deposition of collagen fibers in the subepithelium and around the blood vessels. The vitreous deposits were negatively stained by Congo red and appeared blue following Masson-trichrome, staining, which indicated lamina propria hyalinization and fibrosis (Figure 6).

IMP, which is also known as phlebosclerotic colitis, is a rare intestinal ischemia syndrome with gradual onset and progression. It is characterized by thickening of the wall of the right hemicolon and calcification of mesenteric veins. Most cases have been reported in East Asian nations and regions, especially Japan and Taiwan. In 1991, Koyama et al[5] initially described the disease. To distinguish this disease from ischemic colitis associated with arterial diseases, it was termed as “phlebosclerotic colitis” by Yao et al[6] in 2000. In 2003, Iwashita et al[7] advocated the term “idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis”, as the affected site of this disease showed weak inflammatory changes. Most ischemic bowel diseases result from an insufficient arterial supply attributed to atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and embolus[8]. Disturbed venous return may also cause colitis, including IMP as described here. IMP is usually attributed to chronic ischemia of the colon resulting from calcification of the mesenteric venous system that causes venous congestion of the colon and even hemorrhagic infarction.

The disease incidence is low, with mostly chronic and insidious onset. Patients subject to IMP usually present with nonspecific symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting). As the disease mostly involves the right colon, abdominal pain is more common in the right lower abdomen. Patients may be asymptomatic in the early stage of disease but may develop intestinal obstruction and even perforation in the advanced stage of the disease[9,10]. In this study, most of the 8 patients developed abdominal pain and diarrhea. One presented with intestinal obstruction as the first symptom, and another presented with gastrointestinal bleeding, which was basically consistent with existing reports.

The pathogenesis and etiology of IMP remain unclear. IMP is characterized by a defined area and endemic population distribution, and a relationship with a region-specific lifestyle stressed the etiology of this disease[11]. Long-term and frequent ingestion of biochemical substances and toxins is considered to be associated with the disease. Most reported cases of IMP have been associated with the use of herbal medicines and medicinal liquor, most of which contained gardenia fruits[12]. Gardenia fruit is the dried mature fruit of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis. It is a popular crude drug used as a Chinese herb and has been extensively employed for treating cardiovascular, cerebrovascular diseases, hepatobiliary diseases, and diabetes. The main active ingredient of the gardenia fruit is geniposide. As deduced by some scholars, if patients take Chinese herbal drugs containing Gardenia for a long time, the geniposide can be hydrolyzed to genipin by bacteria in intestinal tract, and the absorbed genipin reacts with the protein in mesenteric vein plasma. In addition, collagen gradually accumulates under the mucosa, which subsequently progresses to hyperplastic myointima in the veins, accompanied by fibrosis/sclerosis. The changes ultimately result in venous occlusion[13]. As geniposide refers to one type of glycoside, orally administered geniposide is not directly absorbed after reaching the lower digestive tract. Geniposide is hydrolyzed only after entering the cecum and ascending colon and then transformed to its metabolite, genipin, which permeates the enterocyte membrane as impacted by numerous bacteria in the colon[12]. The transformation and absorption processes have been largely identified in the right colon and transverse colon, which explains the characteristic lesion site of mesenteric venous sclerosis.

As shown in Table 2, a clear male predominance was found among the patients. This trend is different from the female predominance described in existing reports from Japan and Taiwan, which might be explained as follows. In Japan and Taiwan, herbal prescriptions containing geniposide are commonly used and are thought to be effective for female-specific symptoms, which may account for the female predominance[14,15]. However, most of our patients had a history of taking Chinese medical liquors for a long time. Most were male, which may be the reason for male predominance in our study. Region-specific lifestyle may thus contribute to the understanding of the etiology of this disease. In this study, 7 patients had a history of taking the Chinese medical liquors named Wu chia-pee liquor and Wanying die-da wine, which consist of multiple Chinese herbs soaked in liquor and have various effects (e.g., enhancing fitness and optimizing immune responses)[3,14]. Another patient had no history of drinking alcohol and had been taking Biyuanshu oral liquid for a long time to treat chronic rhinitis. The medical liquids used by our 8 patients all contained geniposide, chuan xiong, and angelia dahurica (Table 3). A study by Hiramatsu et al[14] of 25 IMP patients in which geniposide was the only Chinese medicine common to all is further evidence the that Chinese herbal medicines containing geniposide are involved in the pathology of IMP. Nevertheless, whether geniposide is only factor directly involved in the pathogenesis of IMP, or whether it is accompanied by other Chinese medicine in the pathogenesis of IMP, needs to be further determined in larger datasets.

The clinical symptoms of IMP lack specificity, and the diagnosis is largely determined by the results of radiology and colonoscopy[9,16]. Abdominal CT scans show calcifications of the involved superior mesenteric vein and its branches, which are linear and follow the course of the blood vessels. The involved colon wall becomes swollen and thickened[17]. Endoscopy shows a blue or bluish purple mucosa at the lesion site[18], and the color might be attributed to chronic congestion with ischemia or toxins that stained the bowel mucosa[19]. Tortuous and irregular veins can be seen under the mucosa with poor light transmission. In severe cases, the vessels might disappear. Colonic mucosa was Hyperemia and edema of the colon are sometimes accompanied by erosion or ulcer. The lesions are continuous and the chronic course of disease involves spread from the ileocecal to the anal side. IMP mainly affects the right colon but may also involve the left colon and extend to the sigmoid colon, but generally does not involve the terminal ileum.

In this study, 2 patients had phlebosclerosis extending to the left colonic vein branch, 1 had chronic nephritis, and 1 had been treated 5 years previously with endocrine and radiotherapy for prostate cancer, which are rare in IMP[2,20]. The investigators speculated that poor renal function and long-term treatment of malignant tumors prolong the clearance of genipin, an active metabolite of geniposide, which allows genipin to accumulate in the branches of the veins following absorption, thus aggravating the severity of mesenteric venous sclerosis and reducing the absorption capacity of the colon. Genipin, that is not completely absorbed by the ascending and transverse colons, is absorbed from the left colon, leading to sclerosis and calcification of the left colon venous branch. In addition, systemic microvascular disease complicating diabetes and resulting in chronic hypoxia may increase the vulnerability of colon wall and colon vein[1]. Consequently, chronic nephritis, malignant tumors, and diabetes may increase the risk of the progression of IMP, as shown in Figure 6.

As shown in Figure 7, the severity of IMP is related to the drinking index, which reflects the daily intake of liquid medicine and the duration of contact. The effect on vessel wall is time- and dose-dependent, and that may be related to colonic flora and colonic absorption capacity. IMP has characteristic manifestations on both CT and endoscopy, which make it is relatively easy to diagnose. Conventional histopathology shows fibrosis and calcification of the vein wall and collagen deposition around the vessels. Because of the superficial location of the lesions, the pathological value of the specimens taken during colonoscopy for the diagnosis of IMP is limited, and the resected specimen may require in-depth observation. The treatment strategy for IMP can be determined on an individual basis. Patients with mild or asymptomatic symptoms can be treated conservatively, which will stop progress after the exposure to pathogenic ingredients is stopped (e.g., the use of Chinese herbal medicine). Surgical treatment is necessary if severe complications such as colonic obstruction, necrosis, perforation, or massive intestinal bleeding occur[21]. However the presence of poor circulation may mean that colon surgery is not an appropriate treatment, and it must be chosen with care.

This study evidence supports geniposide as most likely to be involved in the pathology of IMP. Clinical conditions including chronic nephritis, malignant tumors, and diabetes mellitus, may be the risk factors of IMP. It is recommended that long-term use of Chinese herbs and medical liquors should be avoided, especially prescriptions or formulations containing gardenia. Both endoscopic and radiologic examinations can lead to a conclusive diagnosis even if biopsy results are insufficient or inconclusive.

Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis (IMP) is a rare disease, and its etiology and risk factors remain uncertain.

In terms of IMP etiology, the association with a region-specific lifestyle has been a concern. IMP is believed to be linked to chronic and frequent ingestion of biochemicals and toxins.

The objective was to explore the possible relationship between Chinese herbal liquid containing geniposide and IMP and to identify some clinical factors that may lead to disease progression.

The disease computed tomography (CT) score was calculated from the distribution of mesenteric vein calcification and colon wall thickening on CT images. The drinking index of medicinal liquor was calculated from the daily intake and drinking years. The correlation between the drinking index and the disease CT score was analyzed by Spearman’s correlation analysis. Comparison of the herbal ingredients included in the liquid prescriptions, allowed identification of possibly toxic agents as a pathogenic factor.

Geniposide was the only Chinese medicine in common with previous studies. Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed that the median CT disease score was positively correlated with the median drinking index (r = 0.842, P < 0.05).

Geniposide is most likely involved in the pathology of IMP, and its effect is time- and dose-dependent. Chronic nephritis, malignant tumors, diabetes mellitus, and other clinical symptoms may be risk factors for IMP.

The number of cases in our retrospective study was relatively small, and the pathogenesis of IMP needs to be determined by further study with a larger data set.

| 1. | Chang KM. New histologic findings in idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis: clues to its pathogenesis and etiology--probably ingested toxic agent-related. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee SM, Seo JW. Phlebosclerotic colitis: case report and literature review focused on the radiologic findings in relation to the intake period of toxic material. Jpn J Radiol. 2015;33:663-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guo F, Zhou YF, Zhang F, Yuan F, Yuan YZ, Yao WY. Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with long-term use of medical liquor: two case reports and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5561-5566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Yen TS, Liu CA, Chiu NC, Chiou YY, Chou YH, Chang CY. Relationship between severity of venous calcifications and symptoms of phlebosclerotic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8148-8155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koyama N, Koyama H, Hanajima T, Matsubara N, Fujisaki J, Shimoda T. Chronic ischemic colitis causing stenosis: report of a case. Stomach Intest. 1991;26:455-460. |

| 6. | Yao T, Iwashita A, Hoashi T, Matsui T, Sakurai T, Arima S, Ono H, Schlemper RJ. Phlebosclerotic colitis: value of radiography in diagnosis--report of three cases. Radiology. 2000;214:188-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iwashita A, Yao T, Schlemper RJ, Kuwano Y, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Kikuchi M. Mesenteric phlebosclerosis: a new disease entity causing ischemic colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kusanagi M, Matsui O, Kawashima H, Gabata T, Ida M, Abo H, Isse K. Phlebosclerotic colitis: imaging-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen W, Zhu H, Chen H, Shan G, Xu G, Chen L, Dong F. Phlebosclerotic colitis: Our clinical experience of 25 patients in China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang YY, Lin HH, Lin CC. Phlebosclerotic colitis presenting as intestinal obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:e81-e82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kitamura T, Kubo M, Nakanishi T, Fushimi H, Yoshikawa K, Taenaka N, Furukawa T, Tsujimura T, Kameyama M. Phlebosclerosis of the colon with positive anti-centromere antibody. Intern Med. 1999;38:416-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ohtsu K, Matsui T, Nishimura T, Hirai F, Ikeda K, Iwashita A, Yorioka M, Hatakeyama S, Hoashi T, Koga Y, Sakurai T, Miyaoka M. [Association between mesenteric phlebosclerosis and Chinese herbal medicine intake]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2014;111:61-68. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kang MJ, Khanal T, Kim HG, Lee DH, Yeo HK, Lee YS, Ahn YT, Kim DH, Jeong HG, Jeong TC. Role of metabolism by human intestinal microflora in geniposide-induced toxicity in HepG2 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35:733-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hiramatsu K, Sakata H, Horita Y, Orita N, Kida A, Mizukami A, Miyazawa M, Hirai S, Shimatani A, Matsuda K, Matsuda M, Ogino H, Fujinaga H, Terada I, Shimizu K, Uchiyama A, Ishizawa S, Abo H, Demachi H, Noda Y. Mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with long-term oral intake of geniposide, an ingredient of herbal medicine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:575-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moschik EC, Mercado C, Yoshino T, Matsuura K, Watanabe K. Usage and attitudes of physicians in Japan concerning traditional Japanese medicine (kampo medicine): a descriptive evaluation of a representative questionnaire-based survey. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:139818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mathew RP, Girgis S, Wells M, Low G. Phlebosclerotic Colitis - An Enigma Among Ischemic Colitis. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2019;9:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li YL, Cheung KK. Thread like calcifications in mesenteric phlebosclerosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1504-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shibata H, Nishikawa J, Sakaida I. Dark purple-colored colon: sign of idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:604-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yamano T, Tsujimoto Y, Noda T, Shimizu M, Ohmori M, Morita S, Yamada A. Hepatotoxicity of gardenia yellow color in rats. Toxicol Lett. 1988;44:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen MT, Yu SL, Yang TH. A case of phlebosclerotic colitis with involvement of the entire colon. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:581-585. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Washington C, Carmichael JC. Management of ischemic colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:228-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lin CM, Quaglio AEV S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH