Published online Apr 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i14.1419

Peer-review started: October 10, 2020

First decision: January 23, 2021

Revised: February 5, 2021

Accepted: March 7, 2021

Article in press: March 7, 2021

Published online: April 14, 2021

Processing time: 177 Days and 6 Hours

Exosomes play an important role in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), but the mechanism by which exosomes participate in MAFLD still remain unclear.

To figure out the function of lipotoxic exosomal miR-1297 in MAFLD.

MicroRNA sequencing was used to detect differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miR) in lipotoxic exosomes derived from primary hepatocytes. Bioinformatic tools were applied to analyze the target genes and pathways regulated by the DE-miRs. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted for the verification of DE-miRs. qPCR, western blot, immunofluorescence staining and ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine assay were used to evaluate the function of lipotoxic exosomal miR-1297 on hepatic stellate cells (LX2 cells). A luciferase reporter experiment was performed to confirm the relationship of miR-1297 and its target gene PTEN.

MicroRNA sequencing revealed that there were 61 exosomal DE-miRs (P < 0.05) with a fold-change > 2 from palmitic acid treated primary hepatocytes compared with the vehicle control group. miR-1297 was the most highly upregulated according to the microRNA sequencing. Bioinformatic tools showed a variety of target genes and pathways regulated by these DE-miRs were related to liver fibrosis. miR-1297 was overexpressed in exosomes derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes by qPCR. Fibrosis promoting genes (α-SMA, PCNA) were altered in LX2 cells after miR-1297 overexpression or miR-1297-rich lipotoxic exosome incubation via qPCR and western blot analysis. Immunofluorescence staining and ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine staining demonstrated that the activation and proliferation of LX2 cells were also promoted after the above treatment. PTEN was found to be the target gene of miR-1297 and knocking down PTEN contributed to the activation and proliferation of LX2 cells via modulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

miR-1297 was overexpressed in exosomes derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes. The lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal miR-1297 could promote the activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, accelerating the progression of MAFLD.

Core Tip: In this study, the expression of miR-1297 was increased in exosomes derived from primary hepatocytes. Exosomal miR-1297 from lipotoxic LO2 (a hepatocyte cell line) could promote LX2 (a hepatic stellate cell line) activation and proliferation by regulating the PTEN/PI3K/ATK pathway. Currently, the study between exosomes and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease is very limited. This is the first time that exosomal miR-1297 from lipotoxic hepatocytes was confirmed to accelerate liver fibrosis, and the new mechanism may become a promising treatment target for metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

- Citation: Luo X, Luo SZ, Xu ZX, Zhou C, Li ZH, Zhou XY, Xu MY. Lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal miR-1297 promotes hepatic stellate cell activation through the PTEN signaling pathway in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(14): 1419-1434

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i14/1419.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i14.1419

Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), which was formerly called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, is highly prevalent worldwide and affects approximately 25% of the global adult population[1]. Recently, a consensus of international experts proposed the terminology change from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to MAFLD in order to better demonstrated the etiological features of this disease[2]. The incidence of MAFLD has been rising rapidly in recent years, and in China the incidence of MAFLD is 15%-30%[3]. MAFLD is characterized by fatty degeneration of the liver due to different metabolic conditions, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, leading to fatty deposition in the liver[4]. Lipid deposition will increase the oxidative stress of cells in the liver, damage normal cell function and finally lead to liver fibrosis[5]. Hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation was regarded as the core part of all kinds of liver fibrosis. The abnormal activation and proliferation of HSCs will cause them to produce more cellular extracellular matrix, destroy the normal structure of liver lobules and eventually result in cirrhosis[6]. However, the exploration of the specific pathogenesis underlying MAFLD is still in the preliminary stages.

Exosomes are circular or cup-shaped lipid bilayer vesicles with diameters of 30-150 nm, which are secreted by the host cells and transfer a variety of compounds, including miRNAs, mRNAs, lncRNAs, DNA and proteins[7]. Exosomes derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes could accelerate the activation of HSCs and lead to fibrosis[8]. However, to date, studies on the exact mechanism of exosomal miRNA and MAFLD are still very limited. In this study, we perform exosomal miRNA profiling from lipotoxic hepatocytes and further determine the potential mechanism by which exosomal miRNAs participate in the progression of MAFLD.

Hepatocytes (HCs), including primary HCs (PHCs), a normal human HC cell line (LO2) and a human HSC cell line (LX2) were used in this study. PHCs from male wild-type mice were isolated by pronase perfusion and cultured as reported previously[9]. LO2 cells and LX2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, United States) supplemented with 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), 100 IU/mL penicillin (Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). PHCs were used to obtain exosomes for microRNA sequencing (miRNA seq) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) verification. LO2 cells were used to obtain exosomes for cell incubation, and LX2 cells were used for other experiments. These procedures for PHC isolation were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Shanghai General Hospital.

There were 20 MAFLD patients who shared similar demographic features and personal histories enrolled in this study. Among the 20 MAFLD patients with similar liver fibrosis severity, 10 patients were diagnosed as mild fatty liver while the other 10 patients were diagnosed as severe fatty liver depending on the hepatic steatosis. FibroScan (Echosens, Paris, France) analysis was applied to assess the controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement of these patients according to the 2017 ASSLD guidelines[10]. The liver stiffness measurement value of these patients showed no significant difference. Patients with controlled attenuation parameter values from 265 dB/m to 295 dB/m were regarded as mild fatty liver, while patients with controlled attenuation parameter values over 295 dB/m were defined as severe fatty liver. Serum exosome samples from these patients were collected for miRNA qPCR. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Shanghai General Hospital, and written informed consent was provided by all patients. The clinical features of the patients enrolled in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Exosomes from PHCs, LO2 cells and human serum samples were isolated using an ultracentrifugation method that was reported in a previous study[11]. To obtain the lipotoxic exosomes, we treated PHCs and LO2 cells with 200 μmol/L palmitic acid (PA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) or 5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) (diluted in phosphate buffered saline, Sigma-Aldrich) as the vehicle control for 24 h. Then, exosomes were isolated from the cell culture medium. For experiments related to exosome incubation, LX2 cells were treated with 50 µg/mL LO2 exosomes for 48 h.

To observe the exosome morphology, transmission electron microscopy (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was used. The experimental procedures were performed with assistance from Shanghai Bohao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

To analyze the particle diameter distribution, nanoparticle tracking analysis was performed using a NanoSight NS300 system (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, United Kingdom) as in a previous study[12].

For the exosome uptake experiment, 50 µg/mL LO2-derived exosomes (LO2-exosomes) diluted in phosphate buffered saline were labelled using the red fluorescent dye PKH26 Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) After incubating LX2 with PKH26 labelled LO2-exosomes for 6 h, a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to observe the exosomes that were absorbed by LX2 cells.

The miRNA seq experimental procedures were performed with the assistance of Bohao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The miRNA library was constructed using a TruSeq miRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) following the standard procedures of the manufacturer’s instructions.

Low-quality reads and adapters were filtered out from the raw reads to obtain clean reads. The clean reads were aligned against the miRBase database, and the expressions of miRNAs in each sample were determined. Differentially-expressed miRNAs were screened using edgeR, under the following criteria: |log2 (fold-change)| ≥ 1 and P < 0.05. Heatmaps of gene expression were generated with MeV software (MeV Ltd., Stockport, United Kingdom).

Target gene prediction was performed for the significant differentially expressed miRNAs (DE-miRs). GO and pathway enrichment analyses were performed for the target genes using the Gene Ontology Database and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

For cell transfection, negative control mimics (mi-NC) and miR-1297 mimics (mi-miR) were used to overexpress miR-1297. Small interfering RNA for the negative control (si-NC) and small interfering RNA for PTEN were used to knock down PTEN. Cell transfection was conducted using Lipofectamine 2000 Regent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All of the above vectors were purchased from GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

The luciferase reporter assay experiment was conducted using the pGL3-basic luciferase vector (Promega, Madison, WI, United States). The 3’-UTR sequence of PTEN predicted to interact with miR-1297, together with a corresponding mutated sequence within the predicted target sites, were synthesized and inserted into the luciferase reporter (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) to generate PTEN wild-type or PTEN mutant (primers shown in Supplementary Table 2). The pGL3-basic luciferase vector containing PTEN wild-type or PTEN mutant were cotransfected with miR-1297 mimics or negative control mimics using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). After transfection, cells were incubated in suitable conditions for 24 h. The Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega) was used to assess the relative luciferase activity in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luciferase values were normalized to those of Renilla luciferase.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed using Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) and Hieff First Strand cDNA Synthesis Super Mix (Applied Biosystems). β-actin was used as the internal reference to measure the mRNA expression of specific genes. U6 was used to normalize the expression of specific miRNA. Primers used in this research were fully listed in Supplementary Table 2.

These included antibodies were used for western blotting analysis: anti-TSG101 (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA, United States), anti-CD63 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States), anti-PCNA (1:500, Abcam), anti-α-SMA (1:1000, Abcam), anti-PTEN (1:1000, Abcam), anti-TGFβ1 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-SMAD3 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-p-SMAD3 (1:1000, Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:2000, Abcam). HRP-conjugated IgG (1:5000, Abcam) was used as the secondary antibody.

Antibodies against α-SMA (1:100, Abcam) and 4’ 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Abcam) were used for immunofluorescence staining. Alexa Fluor 594 AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as the secondary antibody. The laser microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to capture the representative images.

The proliferation of HSCs was detected by an ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine staining (EdU) cell lighting kit (RiboBio, Shanghai, China). The cell nuclei were stained using Hoechst (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The laser microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to capture the representative images.

The SPSS software (version 22.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) were applied to analyze all the data presented in this study. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD for at least three independent experiments for each group. Continuous variables showing a normal distribution were analyzed by an independent-samples t-test or one-way ANOVA. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

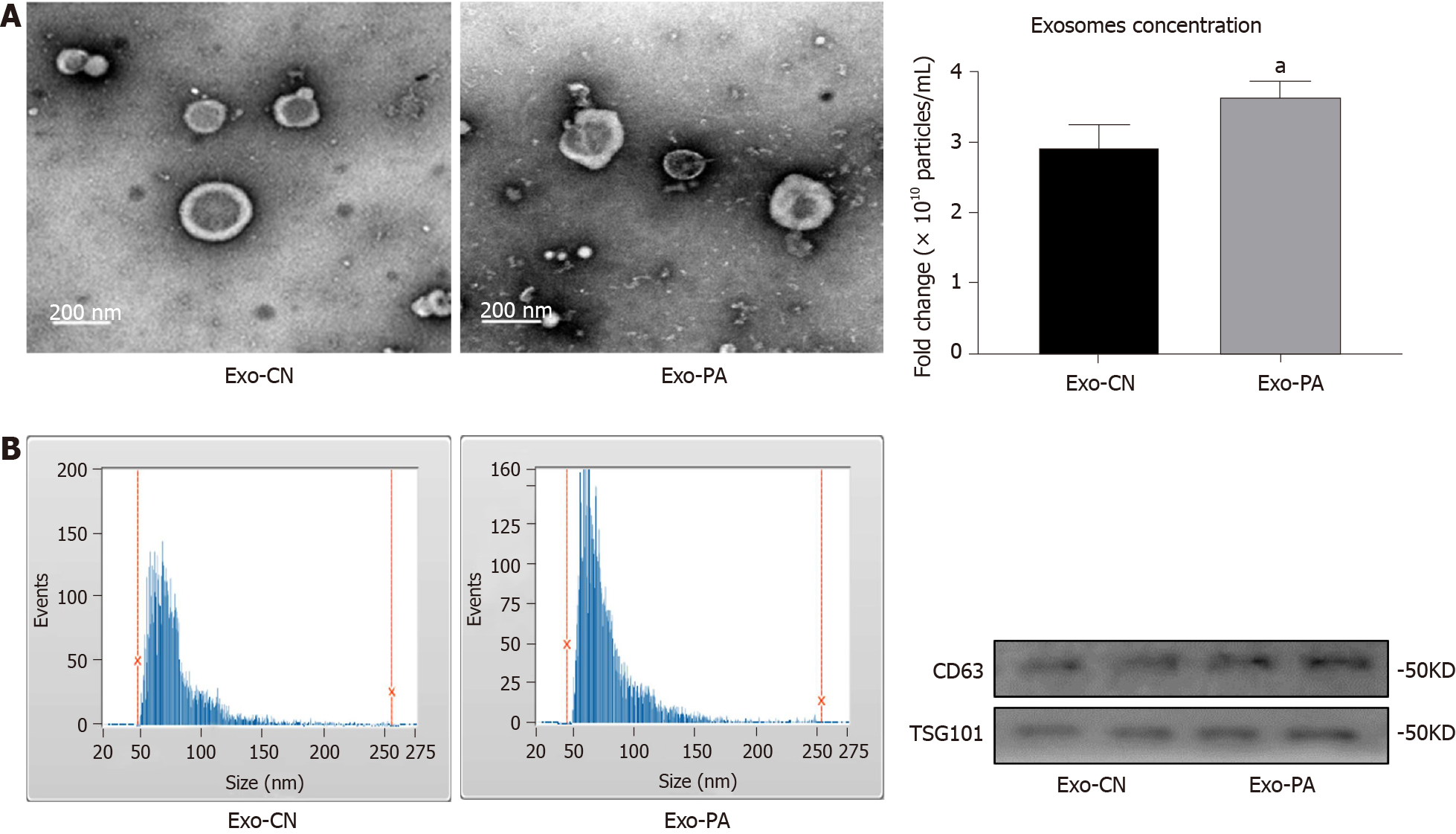

Many studies have clarified that exosomes can participate in a variety of metabolic diseases, but the function of exosomes in MAFLD remains unclear. First, the morphology of exosomes derived from PA-treated (Exo-PA) PHCs or vehicle-treated (Exo-CN) PHCs was observed by transmission electron microscopy. Exosomes were small, quasi-circular vesicles with an intact membrane structure (Figure 1A). Then, exosome size and particle concentration were assessed via nanoparticle tracking analysis. Exosomes with a diameter of 50-150 nm accounted for 87.50% (Exo-PA) and 81.70% (Exo-CN) of all vesicles, which met the standard of high-quality exosomes (Figure 1B). In addition, the concentration of Exo-PA was significantly higher than that of Exo-CN (P < 0.05, Figure 1C). Finally, the exosomal markers CD63 and TSG101 could be observed in both Exo-PA and Exo-CN (Figure 1D). These results indicated that the method we used could obtain high-quality exosomes for follow-up research.

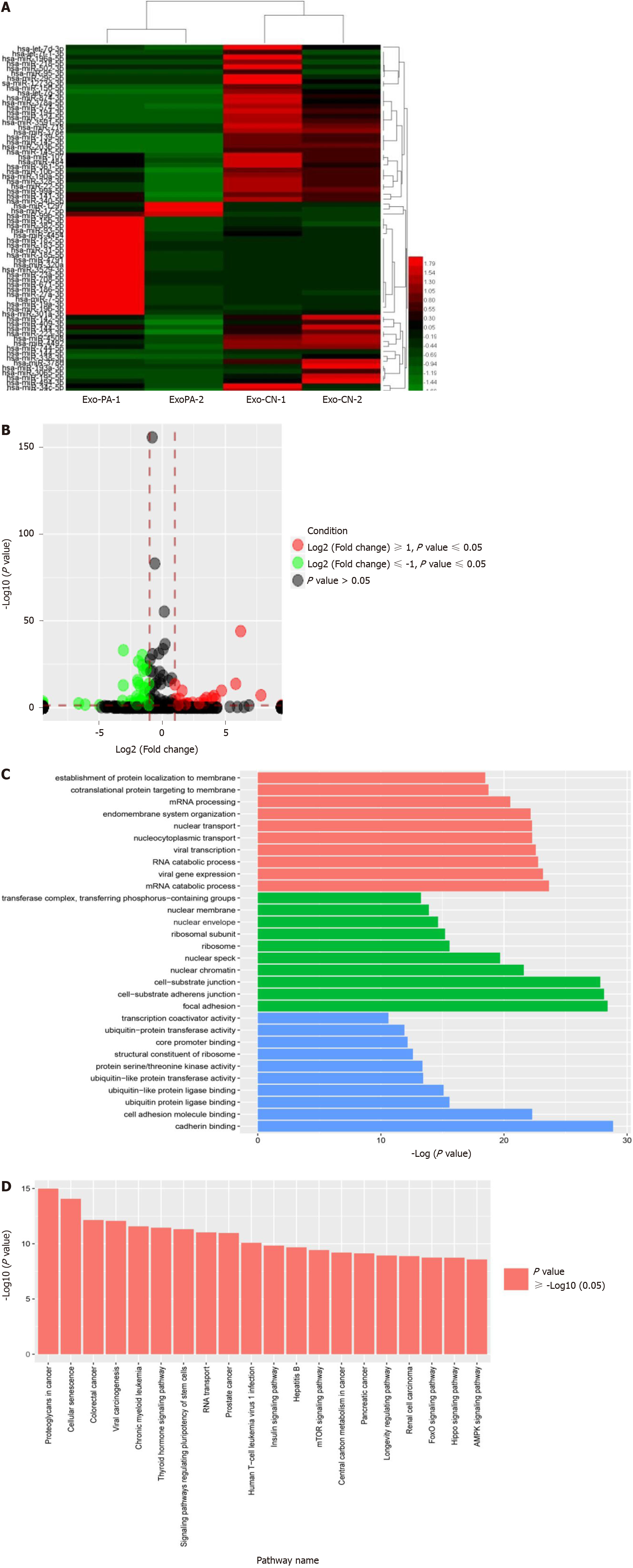

To explore the differentially abundant exosomal miRNAs of lipotoxic HCs, we detected the miRNA expression profiles in Exo-PA and Exo-CN using miRNA seq. According to the results, 61 miRNAs were differentially expressed (P < 0.05) with a fold change > 2 (defined as DE-miR) in the Exo-PA group compared with the Exo-CN group. Among the 61 miRNAs, 20 were upregulated, and 41 were downregulated (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, three upregulated miRNAs had a fold change > 5 (hsa-miR-1297, hsa-miR-708-5p, hsa-miR-671-5p), while two downregulated miRNAs had a fold change > 5 (hsa-miR-718, hsa-miR-193a-3p). miR-1297 was the most highly upregulated miRNA (a 7.81-fold change), and miR-718 was the most highly downregulated miRNA (a 6.62-fold change) in the Exo-PA group. Heatmaps and the volcano map of gene expression are shown based on the expression of these DE-miRs (Figure 2A and 2B).

GO functional enrichment analysis was performed for the DE-miRs to explore the target gene function. The results revealed that these DE-miRs were associated with ten cell components, ten molecular functions and ten biological processes. Among these functions, seven functions were related to ubiquitin activity, which plays an important role in liver fibrosis. The results of the level 2 GO term enrichment analysis are presented in Figure 2C.

According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis, there were 20 significantly enriched pathways. Based on a literature review, four pathways, the AMPK, PI3K-AKT, Hippo and Ras pathways, were highly correlated with liver fibrosis (Figure 2D).

Based on the miRNA seq results, 61 DE-miRs were found to be abnormally expressed in the Exo-PA group compared to the control group. miR-1297 was the top upregulated miRNA among these DE-miRs. Furthermore, seven gene functions and four pathways regulated by these DE-miRs were found to be highly correlated with fibrosis.

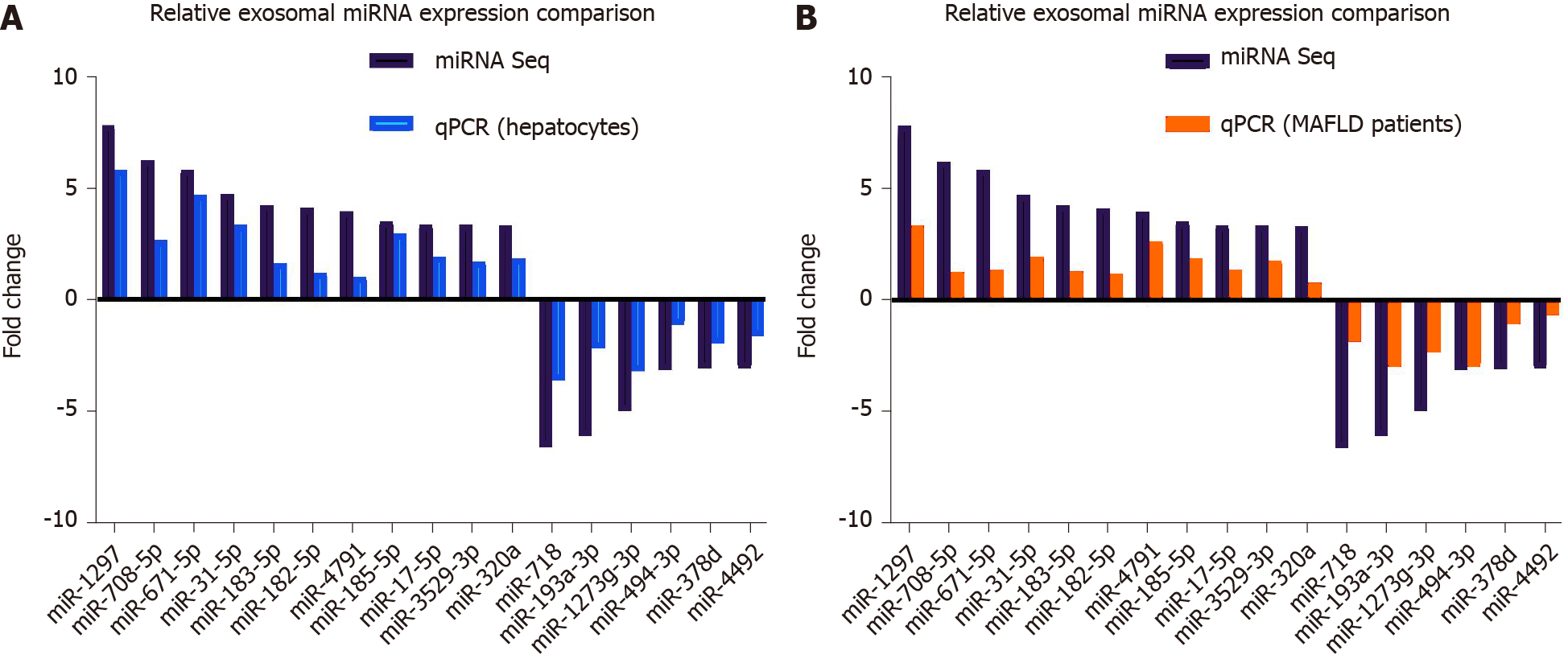

To verify the results of miRNA seq, we measured exosomal DE-miRs with a fold change > 3 in cell culture samples and human serum samples. For cell culture samples, Exo-PA and Exo-CN were used. For human serum samples, exosomes derived from the serum of patients with severe fatty liver or mild fatty liver were selected in order to clarify the actual change of miR-1297 during the pathogenesis of MAFLD.

In cell culture samples, miR-1297 was the top upregulated candidate with a 5.83-fold change in the Exo-PA group compared to the Exo-CN group, while miR-718 was also the top downregulated miRNA with a 3.62-fold change, which was consistent with the results of miRNA seq. The detailed expression levels for the DE-miRs are shown in Figure 3A.

In human serum exosomal samples from exosomes derived from the serum of patients with mild fatty liver, miR-1297 had the greatest upregulation (a 3.32-fold change) compared to exosomes derived from the serum of patients with severe fatty liver among all the DE-miRs, while miR-193a was the top downregulated miRNA with a 2.96-fold change. The detailed expression levels for the DE-miRs are shown in Figure 3B.

Although the results of cell culture samples did not completely parallel the results of human serum samples, miR-1297 showed a higher expression level in both groups. Therefore, miR-1297 was finally selected for follow-up research. The above findings suggested that the expression levels of exosomal miR-1297 from lipotoxic HCs were significantly upregulated.

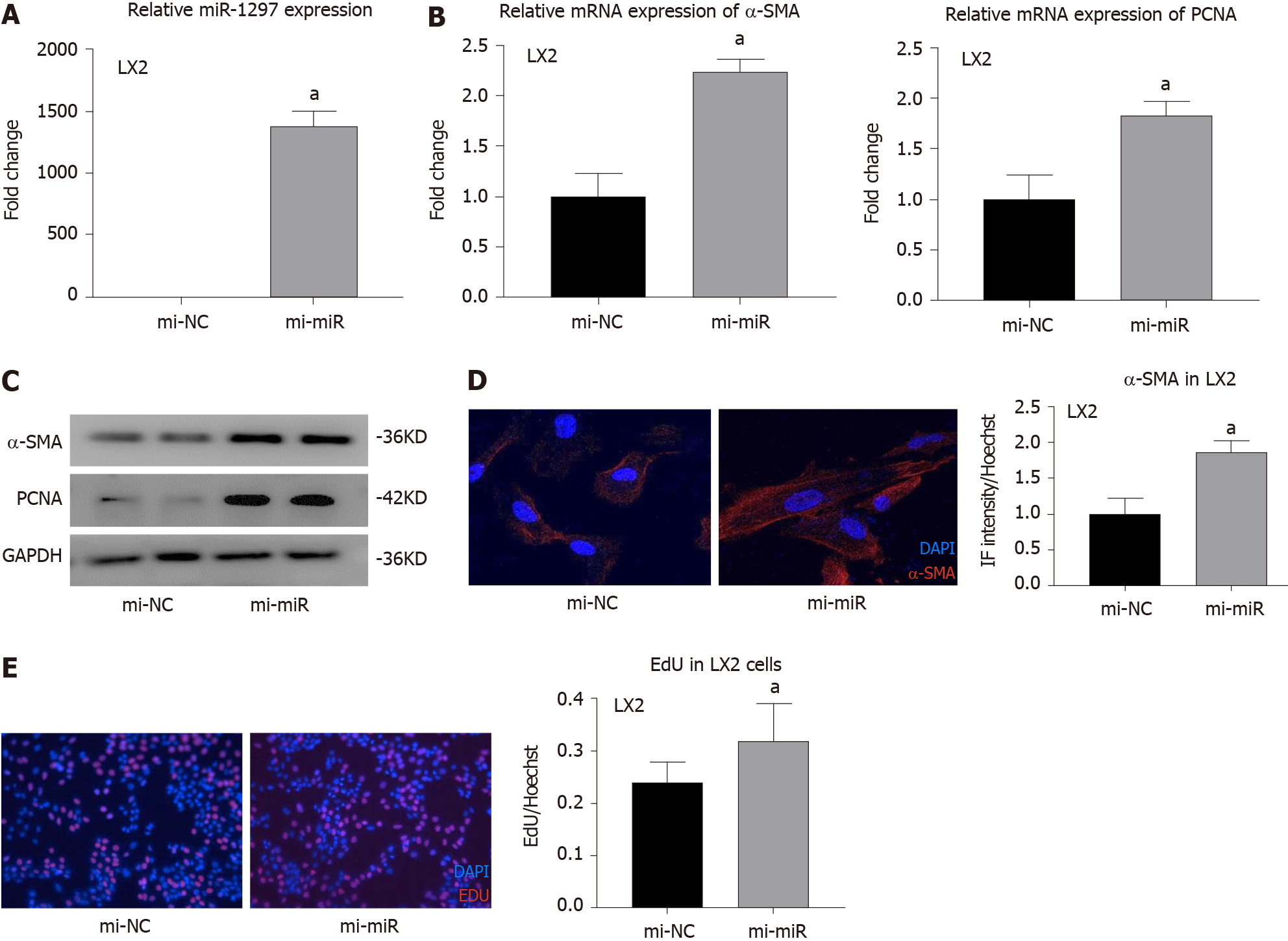

Currently, there is no research related to miR-1297 and liver fibrosis. To explore the effect of miR-1297 on HSCs, we first transfected the hepatic stellate cell line LX2 with miR-1297 mimics (mi-miR) or miRNA negative control mimics (mi-NC). After transfection, the expression was upregulated approximately 1400 times in the mi-miR LX2 cells (Figure 4A). Because α-SMA is an activation marker of HSCs, the expression of α-SMA could reflect collagen production when HSCs are activated. After miR-1297 overexpression in LX2, the mRNA and protein levels of α-SMA were increased (Figure 4B and 4C). In addition, immunofluorescence analysis further revealed that the relative red fluorescence intensity of α-SMA (red fluorescence) was markedly increased in the mi-miR LX2 cells compared to the mi-NC cells (mi-miR: 1.87 ± 0.15 vs mi-NC: 1.00 ± 0.22, Figure 4D). During the process of liver fibrosis, the activation and proliferation of HSCs play a central role. PCNA is a proliferation marker of HSCs. The mRNA and protein levels of PCNA were found to be significantly elevated in the mi-miR LX2 cells compared to the mi-NC LX2 cells (Figure 4B and 4C). In addition, an EdU assay was conducted to evaluate the proliferation of HSCs. As shown in Figure 4E, 32.10% of the mi-miR LX2 cells incorporated EdU, while only 24.15% of the mi-NC LX2 cells were EdU positive, which revealed that miR-1297 could promote the proliferation of LX2 cells as well.

These results proved that miR-1297 could accelerate HSC activation and proliferation.

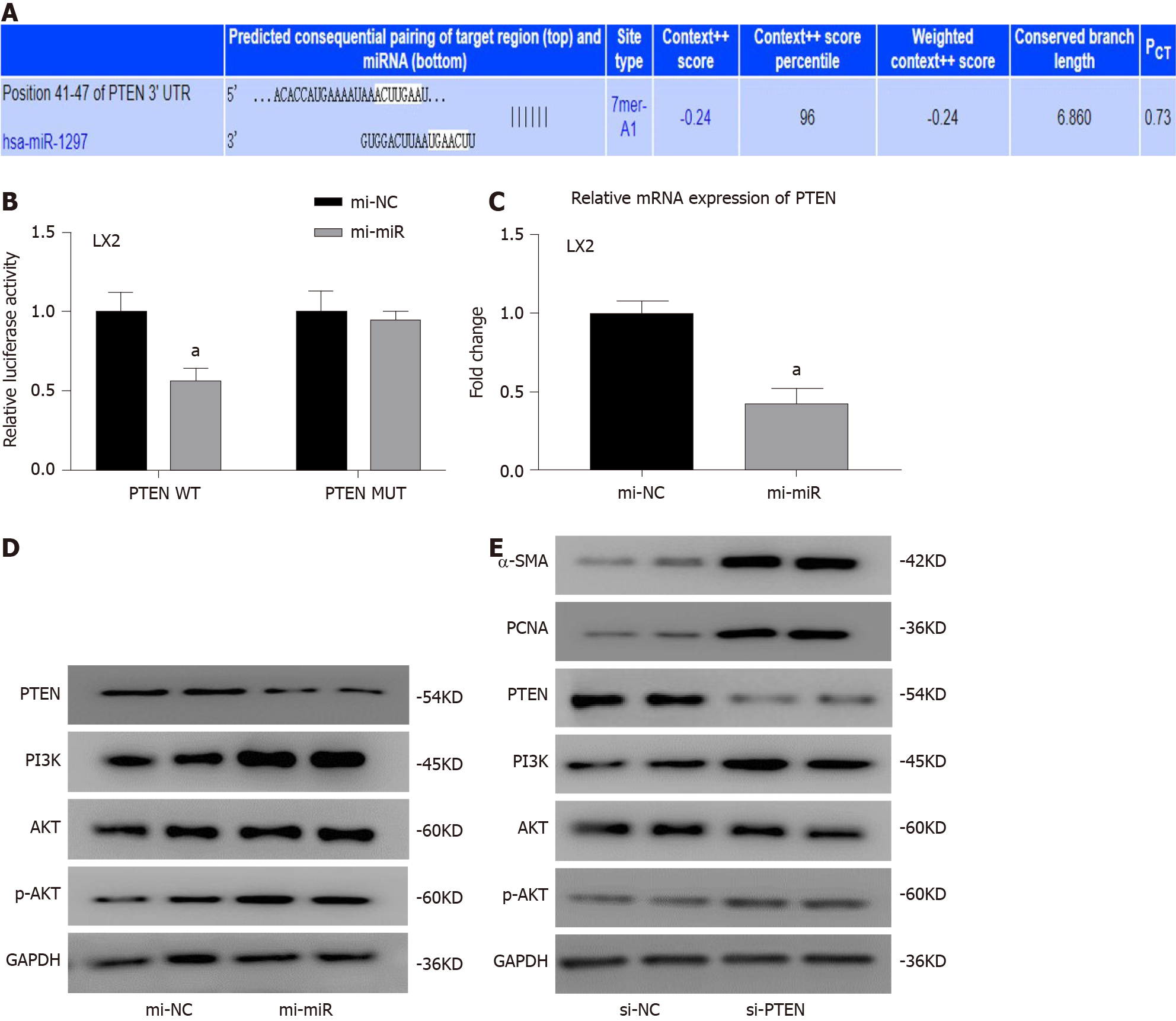

As miR-1297 was found to promote HSC activation and proliferation in LX2 cells, we tried to find the target gene it may regulate to exert its function. In the TargetScan database (http://www.targetscan.org/, Figure 5A), a total of three fibrosis-related genes, COL10A1, PTEN and TRAF3, were selected. A previous study suggested that PTEN was found to be the target gene of miR-1297 in human cervical carcinoma cells[13], so a luciferase reporter assay was conducted to determine the relationship of miR-1297 and PTEN in LX2 cells. In the PTEN wild-type group, the relative luciferase activity in the mi-miR LX2 cells was decreased compared with that in the mi-NC LX2 cells (mi-NC: 1.00 ± 0.14 vs mi-miR: 0.56 ± 0.12) (Figure 5B). However, in the PTEN mutant group, there were no obvious luciferase activity changes between the mi-miR and mi-NC LX2 cells (Figure 5B), which confirmed that PTEN was the target gene of miR-1297 in LX2 cells. Then, the mRNA and protein levels of PTEN were also found to be significantly inhibited after miR-1297 mimic transfection, which indicated that miR-1297 could negatively regulate the expression of PTEN (Figure 5C and 5D).

Previous studies have shown that PTEN could negatively regulate the downstream PI3K/AKT pathway and accelerate liver fibrosis[14-16]. Therefore, PTEN was knocked down to evaluate its function in HSCs. The protein expression of PI3K and p-AKT (Figure 5D and 5E) was markedly elevated in both the miR-1297 and small interfering RNA for PTEN LX2 cells compared to their control cells, while α-SMA and PCNA were also significantly upregulated (Figure 5E), which revealed that PTEN could negatively regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway and HSC activation. These findings suggested that miR-1297 could modulate the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, accelerating the activation and proliferation of HSCs.

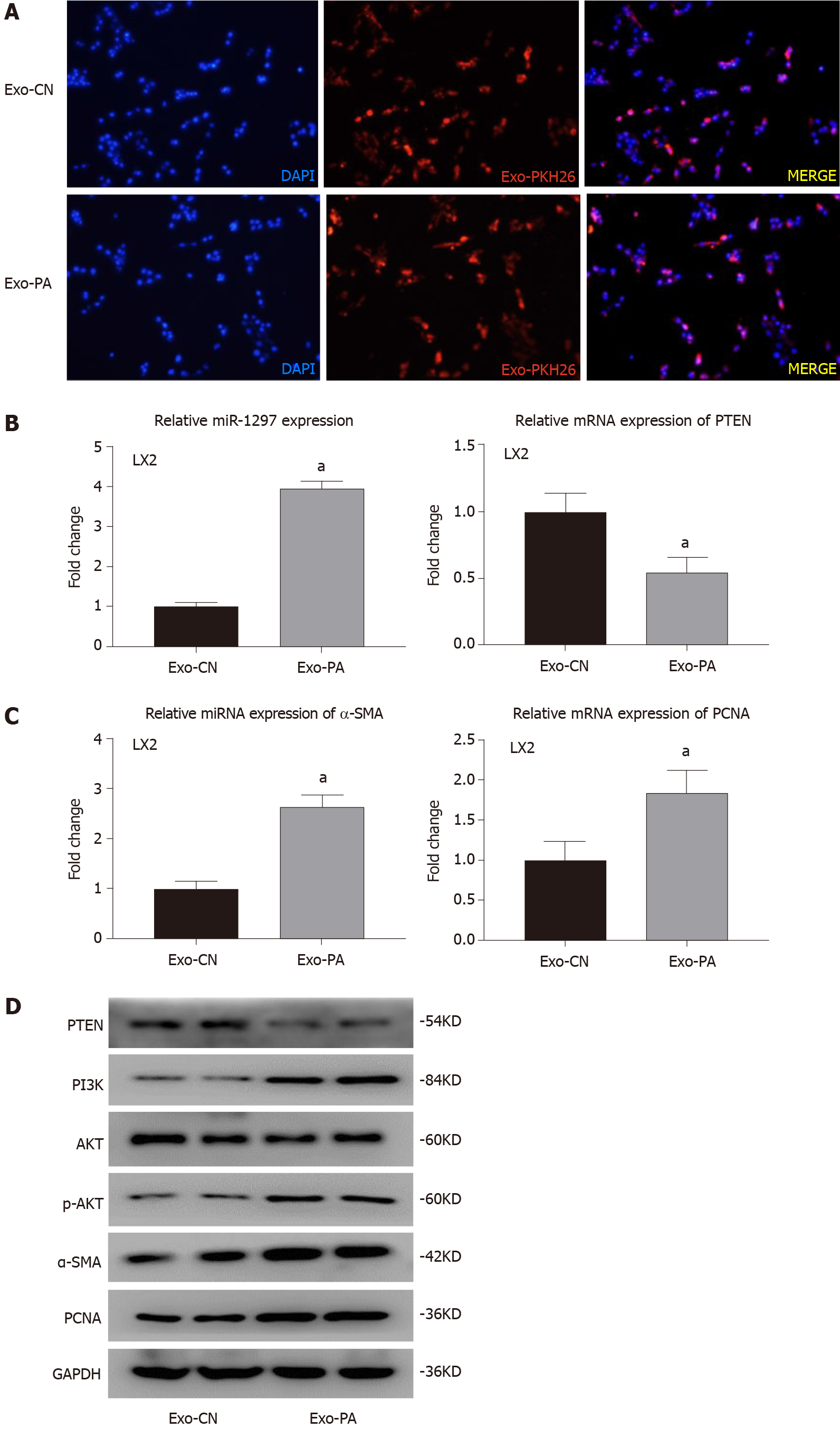

Given the observed effects, miR-1297 was found to promote the activation and proliferation of LX2. To further determine the function of lipotoxic HC-secreted exosomes (HC-Exos) on HSCs, we incubated LX2 cells with exosomes from PA-treated LO2 cells or exosomes from CN-treated LO2 cells. Through the exosome uptake experiment, both Exo-PA and Exo-CN were observed to be engulfed by LX2 cells, suggesting that HC-Exos were successfully taken up by the recipient HSCs (Figure 6A).

miR-1297 was overexpressed after Exo-PA treatment (Exo-PA: 3.95 ± 0.18 vs Exo-CN: 1.00 ± 0.11), while the mRNA and protein levels of PTEN were obviously decreased (Figure 6B and 6D). In addition, the expression of PI3K and p-AKT was significantly increased in the Exo-PA-treated LX2 cells, indicating that miR-1297 modulated the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway after lipotoxic HC-Exo treatment (Figure 6D).

In addition, the expression of α-SMA was found to be significantly upregulated in the Exo-PA LX2 group (Figure 6C and 6D). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a remarkable overexpression of α-SMA (red fluorescence) in the Exo-PA-treated LX2 cells (Exo-PA: 1.68 ± 0.21 vs Exo-CN: 1.00 ± 0.16) (Figure 6E). The mRNA and protein levels of PCNA were markedly elevated in the Exo-PA group as well (Figure 6C and 6D). The proportion of EdU-incorporated LX2 cells was dramatically elevated (Exo-PA: 0.41 ± 0.06 vs Exo-CN: 0.21 ± 0.04) (Figure 6F).

Taken together, these results demonstrated that lipotoxic HC-Exos could transfer exosomal miR-1297 to recipient HSCs, thus promoting HSC activation and proliferation by modulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway.

MAFLD is highly prevalent worldwide and may become the leading cause of end-stage liver disease in the coming decades[17]. Because the majority of MAFLD patients do not show any symptoms, MAFLD may further evolve into liver fibrosis or even hepatocellular carcinoma[18]. Recently, an increasing number of studies focused on the relationship between exosomes and MAFLD-related fibrosis[12], but the exact mechanisms by which exosomes participate in fibrosis remain unclear. In our present research, we observed that the exosomal miR-1297 expression was significantly upregulated in lipotoxic HCs. Furthermore, a novel mechanism through which exosomal miR-1297 mediates cellular communication between HCs and HSCs, subsequently contributing to HSC activation via the PTEN/PI3K/ATK pathway, was confirmed.

Exosomes have been identified as important mediators for cell-cell communication by transferring various biological components, such as miRNAs, lncRNAs and proteins[19]. The evidence that exosomes played an important role in the process of liver fibrosis, acting as a means of communication among different hepatic cells, have been confirmed by multiple studies[20]. Exosomal miR-223 from natural killer cells and exosomal miR-181-5p from mesenchymal stem cells were found to inhibit HSC activation by modulating autophagy[21,22]. Lipopolysaccharide-activated THP-1 macrophages could release exosomal miR-103-3p to induce the activation of HSCs[23]. Exosomes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells could alleviate liver fibrosis through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway[24]. However, research on HC-HSC crosstalk is very limited. To determine the effect of lipotoxic HC-Exos on HSCs, we performed exosomal miRNA seq for an MAFLD HC-Exo model in our research. A total of 61 miRNAs were found to be abnormally expressed in the lipotoxic HC-Exo group compared to the control group, and seven gene functions and four pathways regulated by these DE-miRs were found to be highly correlated with fibrosis.

Then miR-1297 was found to be the most highly upregulated miRNA in both lipotoxic PHC-derived exosomes and severe fatty liver patient serum exosomes compared to their control groups via qPCR verification. Cellular exosomes were isolated from cell culture media and could represent an MAFLD cell model progression. We found miR-1297 was significantly upregulated in lipotoxic PHC-derived exosomes. However, sometimes the experimental results were not parallel with the actual disease progression. Therefore, we measured the expression of miR-1297 in serum exosome samples of MAFLD patients. Exosomes derived from serum usually originated from different organs and could reveal a rather complicated but more real condition during the disease progression. In serum exosome samples we also found miR-1297 was markedly overexpressed in severe MAFLD patients. Both results revealed that miR-1297 was obviously upregulated during MAFLD progression, and miR-1297 was finally chosen for the follow-up study.

Previous studies have confirmed the role of miR-1297 in liver diseases. miR-1297 promoted the progression of liver cancer by inhibiting the expression of RB1[25]. Liu et al[26,27] found that miR-1297 could negatively regulate hepatocellular carcinoma progression by modulating EZH2 and HMGA2. But currently, the role of miR-1297 has not been reported in liver fibrosis. To determine the function of miR-1297 in liver fibrosis, the human hepatic stellate cell line LX2 was treated with miR-1297 mimics and miR-1297-rich lipotoxic exosomes in our research. Upregulation of miR-1297 was found to suppress the expression of its target gene PTEN and contribute to the activation and proliferation of LX2 cells.

PTEN is a well-known regulatory gene to suppress tumors and fibrosis, and many studies have demonstrated that it can prevent the development of various fibrotic-related diseases, such as renal, lung and liver fibrosis[28-30]. The loss of PTEN induced by hypoxia inducible factor-1 promoted HSC activation by regulating the P65 signaling pathway[30]. miR-1273g-3p modulated the activation and apoptosis of HSCs by directly targeting PTEN in HCV-related liver fibrosis[31]. In addition, PTEN inhibited macrophage activation by regulating the PI3K/Akt/STAT6 signaling pathway in hepatic Kupffer cells and alleviated liver fibrosis[32]. In the present study, PTEN was confirmed to be the target gene of miR-1297. High expression levels of miR-1297 induced by miR-1297 mimics and miR-1297-rich lipotoxic HC-Exos could negatively regulate PTEN in LX2, inhibiting its function in preventing liver fibrosis. Therefore, the expression of fibrosis-related genes (α-SMA and PCNA) was found to be increased after miR-1297 overexpression, miR-1297-rich lipotoxic HC-Exo incubation or PTEN knockdown, which was hypothesized to explain why miR-1297 could promote HSC activation.

The progression of liver fibrosis is a complex physiological process, including the regulation of multiple signaling pathways, such as the TGFβ1/SMAD, MAPK and PI3K/ATK pathways[33]. The PI3K/ATK pathway is a classic pathway regulated by PTEN that participates in a variety of biological functions, including cell growth, proliferation and differentiation[34]. It has been reported that PTEN could hydrolyze PI3K protein, thereby phosphorylating AKT and stimulating fibroblast accumulation and myofibroblast differentiation[35,36]. Our results demonstrated that the low expression of PTEN induced by miR-1297 or small interfering RNA could promote the protein expression of PI3K and p-AKT, thus elevating the expression of fibrosis-related genes (α-SMA and PCNA), which may explain the downstream molecular mechanism by which miR-1297 regulates PTEN and activates HSCs.

Taken together, our research is the first to clarify that exosomal miR-1297 originating from PA-treated HCs could promote the activation and proliferation of HSCs by targeting the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway and accelerate the progression of liver fibrosis. This molecule may become a new target for the treatment of MAFLD in the future.

Accumulating evidence has revealed that exosomes play an important role in the progression of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, but the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Previous studies demonstrated that exosomes from lipotoxic hepatic cells could contribute to hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation, but the specific cellular crosstalk interaction was not fully illustrated. We aimed to figure out if exosomal microRNA could participate in this procedure.

To determine the role of exosomal miR-1297 in the metabolic-associated fatty liver disease cell model.

miRNA sequencing was conducted to screen differentially-expressed microRNAs. In vitro experiments like quantitative real-time PCR analysis, western blot, immunofluorescence and ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine staining were performed to explore the function of exosomal miR-1297 on HSC activation and proliferation.

miR-1297 was obviously overexpressed in exosomes derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes. The lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal miR-1297 could promote the activation and proliferation of HSCs through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

The lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal miR-1297 could accelerate the progression of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease in a cell model.

This study provided some new evidence on the crosstalk between hepatocyte-secreted exosomes and HSC. miR-1297 may become a potential target for the treatment of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

| 1. | Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, Bugianesi E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4054] [Cited by in RCA: 4012] [Article Influence: 501.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1999-2014. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2367] [Cited by in RCA: 2408] [Article Influence: 401.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Fan JG, Kim SU, Wong VW. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J Hepatol. 2017;67:862-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 848] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 93.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Zhang X, Ji X, Wang Q, Li JZ. New insight into inter-organ crosstalk contributing to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Protein Cell. 2018;9:164-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Machado MV, Diehl AM. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1769-1777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schuppan D, Surabattula R, Wang XY. Determinants of fibrosis progression and regression in NASH. J Hepatol. 2018;68:238-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Qin J, Xu Q. Functions and application of exosomes. Acta Pol Pharm. 2014;71:537-543. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lee YS, Kim SY, Ko E, Lee JH, Yi HS, Yoo YJ, Je J, Suh SJ, Jung YK, Kim JH, Seo YS, Yim HJ, Jeong WI, Yeon JE, Um SH, Byun KS. Exosomes derived from palmitic acid-treated hepatocytes induce fibrotic activation of hepatic stellate cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu T, Luo X, Li ZH, Wu JC, Luo SZ, Xu MY. Zinc-α2-glycoprotein 1 attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by negatively regulating tumour necrosis factor-α. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5451-5468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3544] [Cited by in RCA: 5209] [Article Influence: 651.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 11. | Lobb RJ, Becker M, Wen SW, Wong CS, Wiegmans AP, Leimgruber A, Möller A. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 855] [Cited by in RCA: 1330] [Article Influence: 120.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bachurski D, Schuldner M, Nguyen PH, Malz A, Reiners KS, Grenzi PC, Babatz F, Schauss AC, Hansen HP, Hallek M, Pogge von Strandmann E. Extracellular vesicle measurements with nanoparticle tracking analysis - An accuracy and repeatability comparison between NanoSight NS300 and ZetaView. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8:1596016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 13. | Chen Z, Zhang M, Qiao Y, Yang J, Yin Q. MicroRNA-1297 contributes to the progression of human cervical carcinoma through PTEN. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:1120-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hao XJ, Xu CZ, Wang JT, Li XJ, Wang MM, Gu YH, Liang ZG. miR-21 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells through targeting PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2018;38:455-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kumar P, Raeman R, Chopyk DM, Smith T, Verma K, Liu Y, Anania FA. Adiponectin inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation by targeting the PTEN/AKT pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:3537-3545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dong Z, Li S, Wang X, Si L, Ma R, Bao L, Bo A. lncRNA GAS5 restrains CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis by targeting miR-23a through the PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;316:G539-G550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, Wai-Sun Wong V, Yilmaz Y, George J, Fan J, Vos MB. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019;69:2672-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1415] [Cited by in RCA: 1375] [Article Influence: 196.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018;24:908-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1376] [Cited by in RCA: 3188] [Article Influence: 398.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Devhare PB, Ray RB. Extracellular vesicles: Novel mediator for cell to cell communications in liver pathogenesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2018;60:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cai S, Cheng X, Pan X, Li J. Emerging role of exosomes in liver physiology and pathology. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:194-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Wang L, Wang Y, Quan J. Exosomal miR-223 derived from natural killer cells inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation by suppressing autophagy. Mol Med. 2020;26:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Qu Y, Zhang Q, Cai X, Li F, Ma Z, Xu M, Lu L. Exosomes derived from miR-181-5p-modified adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent liver fibrosis via autophagy activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2491-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen L, Yao X, Yao H, Ji Q, Ding G, Liu X. Exosomal miR-103-3p from LPS-activated THP-1 macrophage contributes to the activation of hepatic stellate cells. FASEB J. 2020;34:5178-5192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rong X, Liu J, Yao X, Jiang T, Wang Y, Xie F. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes alleviate liver fibrosis through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu C, Wang C, Wang J, Huang H. miR-1297 promotes cell proliferation by inhibiting RB1 in liver cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:5177-5182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu F, He Y, Shu R, Wang S. MicroRNA-1297 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and apoptosis by targeting EZH2. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:4972-4980. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Liu Y, Liang H, Jiang X. MiR-1297 promotes apoptosis and inhibits the proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting HMGA2. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:1345-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Higgins DF, Ewart LM, Masterson E, Tennant S, Grebnev G, Prunotto M, Pomposiello S, Conde-Knape K, Martin FM, Godson C. BMP7-induced-Pten inhibits Akt and prevents renal fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:3095-3104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tian Y, Li H, Qiu T, Dai J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Cai H. Loss of PTEN induces lung fibrosis via alveolar epithelial cell senescence depending on NF-κB activation. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e12858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Han J, He Y, Zhao H, Xu X. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 promotes liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by activating PTEN/p65 signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:14735-14744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Niu X, Fu N, Du J, Wang R, Wang Y, Zhao S, Du H, Wang B, Zhang Y, Sun D, Nan Y. miR-1273g-3p modulates activation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells by directly targeting PTEN in HCV-related liver fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:2709-2724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wu SM, Li TH, Yun H, Ai HW, Zhang KH. miR-140-3p Knockdown Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Fibrogenesis in Hepatic Stellate Cells via PTEN-Mediated AKT/mTOR Signaling. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60:561-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pierantonelli I, Svegliati-Baroni G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Basic Pathogenetic Mechanisms in the Progression From NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation. 2019;103:e1-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Worby CA, Dixon JE. PTEN. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:641-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Interactions between TGF-β1, canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway and PPAR γ in radiation-induced fibrosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:90579-90604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cheng Y, Tian Y, Xia J, Wu X, Yang Y, Li X, Huang C, Meng X, Ma T, Li J. The role of PTEN in regulation of hepatic macrophages activation and function in progression and reversal of liver fibrosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;317:51-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Balaban YH, Corrales FJ, Inal V, Morales-González JA, Sempokuya T S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH