Published online Feb 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i8.850

Peer-review started: October 30, 2019

First decision: November 22, 2019

Revised: December 4, 2019

Accepted: February 15, 2020

Article in press: February 15, 2020

Published online: February 28, 2020

Processing time: 120 Days and 15.1 Hours

Severe chronic radiation proctopathy (CRP) is difficult to treat.

To evaluate the efficacy of colostomy and stoma reversal for CRP.

To assess the efficacy of colostomy in CRP, patients with severe hemorrhagic CRP who underwent colostomy or conservative treatment were enrolled. Patients with tumor recurrence, rectal-vaginal fistula or other types of rectal fistulas, or who were lost to follow-up were excluded. Rectal bleeding, hemoglobin (Hb), endoscopic features, endo-ultrasound, rectal manometry, and magnetic resonance imaging findings were recorded. Quality of life before stoma and after closure reversal was scored with questionnaires. Anorectal functions were assessed using the CRP symptom scale, which contains the following items: Watery stool, urgency, perianal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, and fecal/gas incontinence.

A total of 738 continual CRP patients were screened. After exclusion, 14 patients in the colostomy group and 25 in the conservative group were included in the final analysis. Preoperative Hb was only 63 g/L ± 17.8 g/L in the colostomy group compared to 88.2 g/L ± 19.3 g/L (P < 0.001) in the conservative group. All 14 patients in the former group achieved complete remission of bleeding, and the colostomy was successfully reversed in 13 of 14 (93%), excepting one very old patient. The median duration of stoma was 16 (range: 9-53) mo. The Hb level increased gradually from 75 g/L at 3 mo, 99 g/L at 6 mo, and 107 g/L at 9 mo to 111 g/L at 1 year and 117 g/L at 2 years after the stoma, but no bleeding cessation or significant increase in Hb levels was observed in the conservative group. Endoscopic telangiectasia and bleeding were greatly improved. Endo-ultrasound showed decreased vascularity, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed an increasing presarcal space and thickened rectal wall. Anorectal functions and quality of life were significantly improved after stoma reversal, when compared to those before stoma creation.

Diverting colostomy is a very effective method in the remission of refractory hemorrhagic CRP. Stoma can be reversed, and anorectal functions can be recovered after reversal.

Core tip: This study evaluated the efficacy of colostomy and stoma reversal in severe chronic hemorrhagic radiation proctopathy. After screening 738 patients, 14 patients in the colostomy group and 25 in the conservative treatment group were included. All 14 colostomy patients achieved complete remission of bleeding, and the colostomy was reversed in 13 patients. The hemoglobin level increased gradually after the stoma. However, no bleeding cessation was observed in the conservative group. Anorectal functions and quality of life were improved after stoma reversal. In conclusion, diverting colostomy is an effective option and can be reversed in severe chronic hemorrhagic radiation proctopathy.

- Citation: Yuan ZX, Qin QY, Zhu MM, Zhong QH, Fichera A, Wang H, Wang HM, Huang XY, Cao WT, Zhao YB, Wang L, Ma TH. Diverting colostomy is an effective and reversible option for severe hemorrhagic radiation proctopathy. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(8): 850-864

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i8/850.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i8.850

Chronic radiation proctopathy (CRP) is a common and sometimes difficult issue after radiotherapy for pelvic malignancies. A permanent change in bowel habits may occur in 90% of patients. After pelvic radiotherapy, 20%-50% of patients will develop difficult bowel function, affecting their quality of life (QOL)[1,2]. CRP can cause more than 20 different symptoms. Rectal bleeding is the most common symptom and occurs in > 50% of CRP patients[1,3]. Transfusion-dependent severe bleeding occurs in 1%-5% of patients[1]. Pathologically, ischemia in the submucosa due to obliterative endarteritis and progressive fibrosis in macroscopic changes are the main causes[4].

Medical treatment consists of topical sucralfate enemas[5], oral or topical sulfasalazine[6], and rebamipide[7]. However, these reagents are only effective in acute or mild CRP, whereas their efficacy is usually disappointing in CRP patients with moderate to severe hemorrhage. More invasive modalities include endoscopic argon plasma coagulation (APC)[8], topical 4%-10% formalin[9-12], radiofrequency ablation[13], and hyperbaric oxygen therapy[14,15], and are currently popular optional treatments for CRP. Most of these modalities lack randomized trial evidence. These treatment options are reported to be effective in controlling mild to moderate bleeding in most of the literature. Nonetheless, severe and refractory bleeding is difficult to manage[1,16]. Furthermore, APC or topical formalin requires multiple sessions for severe bleeding and can cause severe side effects, including perforation, strictures, and perianal pain[17].

Fecal diversion is reported to be effective in the management of severe CRP bleeding[16,18,19], as it can reduce irritation injury to the lesions to decrease hemorrhage[16]. However, the usage of fecal diversion is not adopted as widely as is APC or formalin. Most of the fecal diversion data are from the 1980s, and this option has not been well studied to date. We previously reported one retrospective cohort of CRP patients with severe hemorrhage who received colostomy[16]. The results showed that colostomy can bring much higher remission of severe bleeding (94%) than can conservative treatment (11%) with APC or topical formalin. Pathologically, chronic inflammation and progressive fibrosis are observed after stoma. Diverting stoma is usually thought to be permanent according to Ayerdi et al[20].

Anorectal function and QOL after stoma reversal remain unclear. During the past 3 years, we have successfully performed colostomy reversals in a large cohort of CRP patients with severe bleeding and have follow-up data after colostomy reversal. Here, we report the efficacy of colostomy, the rate of stoma closure of diverting colostomy, and anorectal function after reversal for this series of CRP patients with severe bleeding.

Patients with hemorrhagic CRP who were treated after admission at The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University from March 2008 to December 2018 were enrolled. Medical records and imaging and clinicopathological data were extracted from our electronic database. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University and was performed according to the provisions of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki in 1995 (updated in Tokyo, 2004). Due to the nature of a retrospective study, informed consent was waived.

CRP patients with refractory rectal bleeding who received diverting colostomy or conservative treatments for severe anemia and who needed transfusions were enrolled. Patients who were lost to follow-up, had tumor recurrence, rectal-vaginal fistula or other types of rectal fistulas, or underwent rectal resection with preventive colostomy were excluded because these conditions would affect the evaluation of remission of rectal bleeding.

CRP was diagnosed by the combination of pelvic radiation history for malignancies, symptoms such as rectal bleeding, and endoscopic findings of CRP-specific changes such as telangiectasia and active bleeding in the rectum, as well as exclusion of other bleeding diseases. Hemorrhagic problems, such as tumor recurrence and hemorrhoids, were excluded. Refractory severe bleeding was defined as frequent bleeding and severe anemia with the need for transfusions. At admission, CRP patients in our center were first referred to noninvasive enemas, and if there was no response or recurrence, invasive treatment, such as APC (1-2 rounds) or formalin topical irrigation, was utilized. Conservative treatment failure was defined as no response or recurrence of frequent or severe rectal bleeding after invasive treatments.

In this study, we used a modified subjective-objective management analysis (known as mSOMA) system that we designed previously to assess the severity of rectal bleeding[16]. The advantages of the mSOMA system include both subjective complaints of patients and objective hemoglobin (Hb) levels according to laboratory tests. Remission of bleeding was defined as complete cessation or occasional bleeding that needed no further treatment. The CTCAE score of bleeding was used to assess its severity.

The indications for diverting diversion in hemorrhagic CRP contained the following conditions: Recurrent bleeding and unresponsive to conservative treatments such as endoscopic APC or topical formalin, accompanying severe anemia, and transfusions needed. Transverse loop colostomy and “gunsight” or “cross‘’ type of stoma closure were created according to the standard protocols used in our previous studies[16]. The criteria of stoma closure were as follows: Remission or occasional rectal bleeding, regressive edema in rectal mucosa, good performance of anorectal function, exclusion of tumor recurrence, and no severe CRP complications such as fistula, stricture, and deep ulcer[16].

Patients were scheduled for follow-up through outpatient visits or telephone questionnaires at 6 mo, 9 mo, 1 year, 1.5 years, and 2 years after colostomy. QOL after stoma closure was evaluated according to EORTC QLQ C30 questionnaires[21]. We focused on the following items in this study: The remission rate of bleeding, the rate of stoma reversal, QOL after stoma reversal, dynamic changes of Hb levels, stoma-related complications, and severe CRP complications.

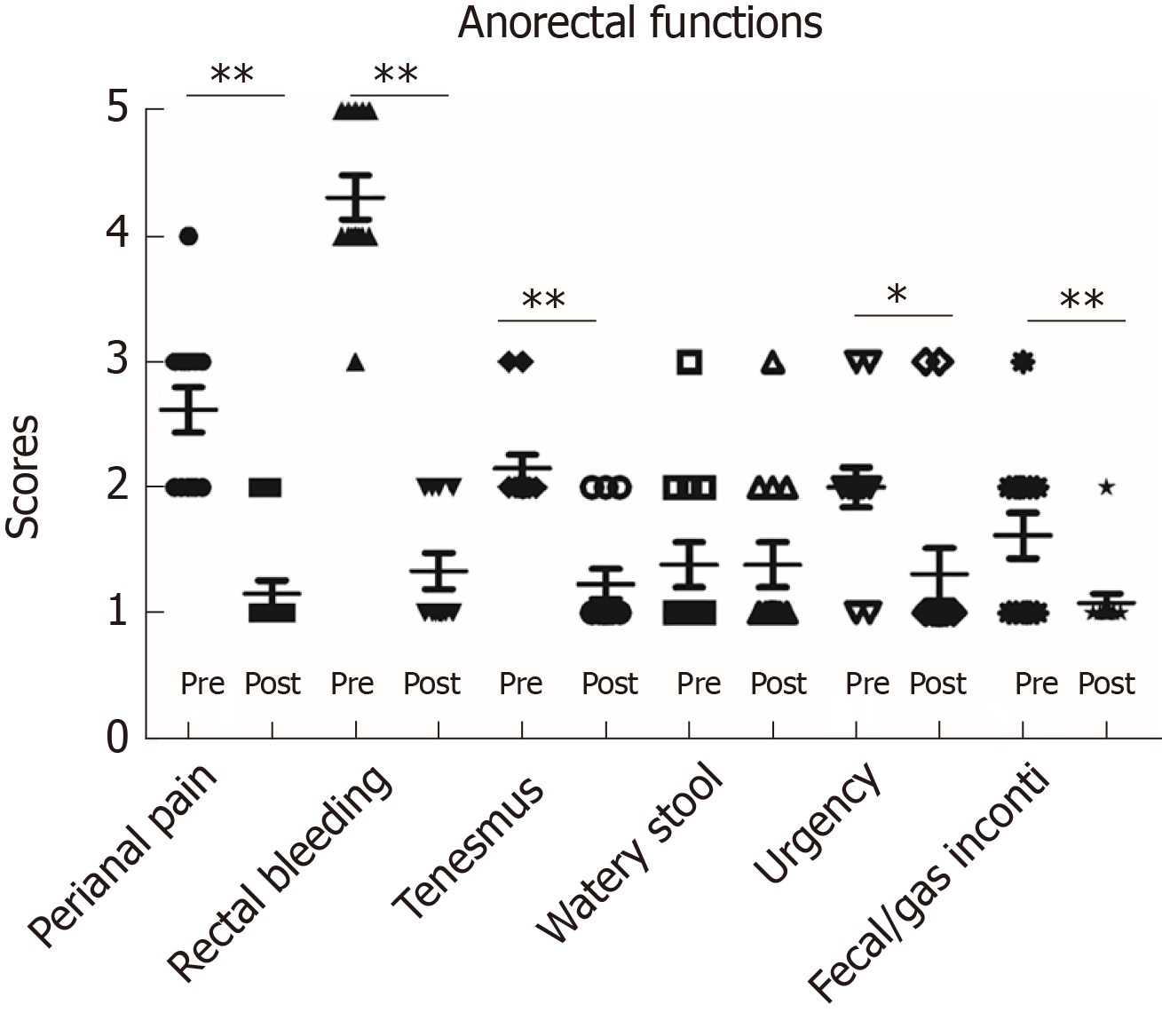

In our previous study, tenesmus, stool frequency, and anorectal pain were common symptoms in active CRP[22]. Because there are no standard scales or scores to assess anorectal function precisely in CRP patients, we developed a new scale system that is a patient self-reported scale of outcomes, namely, the chronic radiation proctopathy symptom scale (CRPSS). The CRPSS considers the following items: Watery stool, urgency, perianal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, and fecal/gas incontinence. The details are provided in Supplementary File 1. For CRP patients treated by colostomy, CRPSS scores were evaluated before stoma and at reversal.

Analyses for continuous variables were performed by Student’s t-test. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was conducted when appropriate. For non-parameter variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

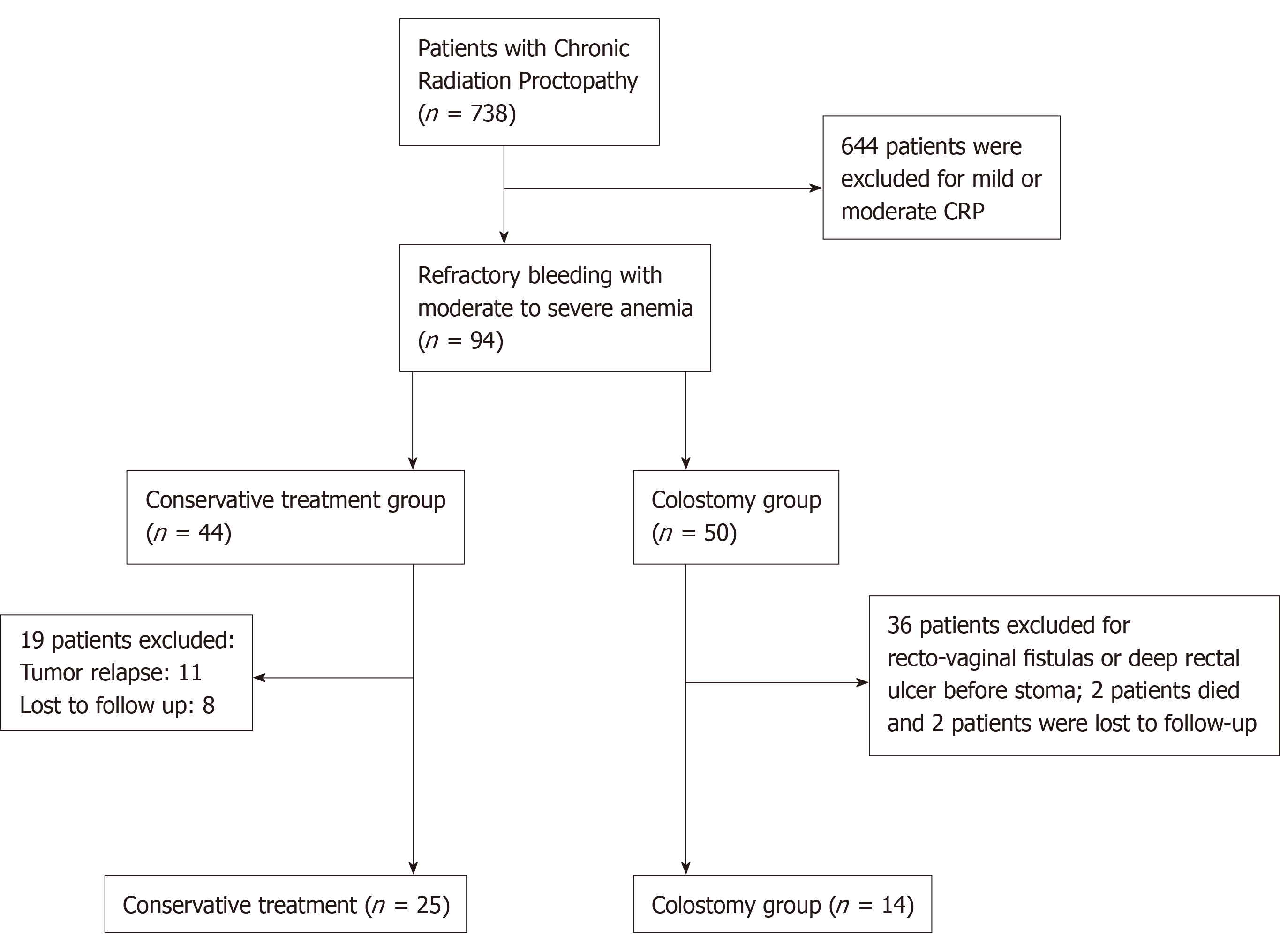

From March 2008 to Feb 2019, 738 continual CRP patients treated in our center were screened. After exclusion of 644 patients with mild or moderate CRP, 94 with refractory bleeding and moderate to severe anemia were further screened. Among them, 50 patients were treated by diverted colostomy and 44 patients were treated with conservative therapies. Among the 50 patients treated by colostomy, 32 were excluded due to recto-vaginal fistulas or deep rectal ulcer with refractory perianal pain before stoma. The remaining 18 patients with refractory bleeding were enrolled. Among them, two died from cancer recurrence and two were lost to follow-up. The remaining 14 patients were enrolled in the final analysis as the colostomy group. For the conservative group, 19 patients were excluded, including 11 with tumor relapse and 8 who were lost to follow-up. Thus, 25 were enrolled in the final analysis (Figure 1). Demographic and baseline characteristics were collected, including the intention-to-treat (ITT) group of 50 colostomies. In the enrolled patients, 14 patients comprised the diverting colostomy group, and 25 cases comprised the conservative treatment group. The primary tumors in most of the patients (33/39, 85%) were cervical cancers. No significant differences in age, sex, type of primary tumor, or radiation dosage were found between the diverting colostomy group and the conservative treatment group or between the ITT colostomy group and the colostomy group (Table 1).

| Variable | Diverting colostomy, n = 14 | Conservative treatment, n = 25 | Colostomy vs conservative, P value | ITT group, n = 50 | ITT group vs colostomy, P value |

| Age, mean ± SD | 61 ± 10.9 | 60.2 ± 2.4 | 0.89 | 59.3 ± 8.7 | 0.767 |

| Sex, female/male | 13/1 | 23/2 | 1.01 | 49/1 | 1.01 |

| Primary cancer | 0.405 | 0.879 | |||

| Cervical cancer | 12 | 21 | 45 | ||

| Endometrial cancer | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Rectal cancer | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Prostate cancer | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Radiation dosage, Gy | 82 ± 15.9 | 83.6 ± 20.5 | 0.825 | 83.4 ± 18.5 | 0.553 |

| Duration of bleeding in mo | 13 ± 4.3 | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 0.042 | 11.3 ± 4.0 | 0.263 |

| Pre-Op transfusion, yes/no | 12/2 | 6/19 | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Pre-Op Hb, g/L (lowest level) | 63 ± 17.8 | 88.2 ± 19.3 | < 0.001 | 80 ± 27.8 | 0.051 |

| Bleeding remission rate | |||||

| Post-Op 3 mo | 12/14 (86%) | 1/25 (4%) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Post-Op 6 mo | 12/14 (86%) | 3/25 (12%) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Post-Op 9 mo | 13/14 (93%) | 5/25 (20%) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Post-Op 1 yr | 14/14 (100%) | 6/25 (24%) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Post-Op 2 yr | 14/14 (100%) | 5/25 (20%) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Bleeding score at initial diagnosis | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Bleeding score after 1 yr of treatment | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.008 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.033 |

In the ITT group, no postoperative follow-ups were conducted other than for the 14 investigated colostomy patients. Higher bleeding scores (P = 0.033) and relatively decreased preoperative Hb levels (P = 0.051, no significant difference) were found in the diverting colostomy group compared to the ITT group because 36 patients in the ITT group underwent colostomy for recto-vaginal fistulas or deep rectal ulcers instead of severe bleeding.

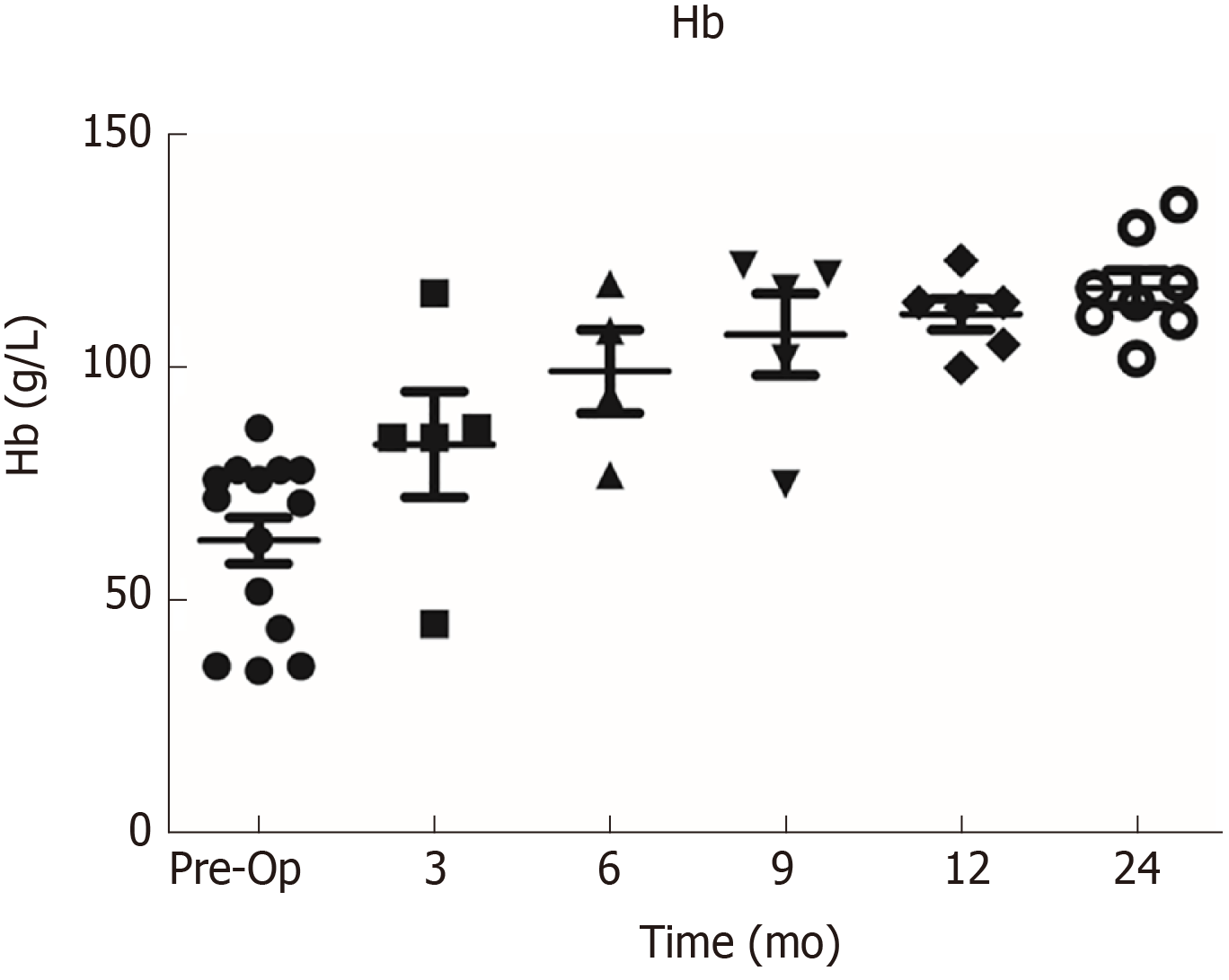

In the colostomy group, the median duration of bleeding was 13.0 mo ± 4.3 mo, and 12 (86%) patients received transfusion before stoma compared to 8.0 mo ± 1.8 mo (P = 0.042) of bleeding duration and 6 (24%) (P < 0.001) transfusions in the conservative group. In the conservative group, 8 patients received formalin irrigation and 4 patients received APC treatments. The preoperative (Pre-Op) Hb was only 63 g/L ± 17.8 g/L in the colostomy group compared to 88.2 g/L ± 19.3 g/L (P < 0.001) in the conservative group. One patient with moderate anemia (Hb of 87 g/L) received colostomy for perianal pain. Another patient with severe anemia (Hb of 78 g/L) did not receive a transfusion due to unavailability of a blood supply before colostomy. The details of the 14 patients are listed in Table 2. Increasing Hb levels were observed from 3 mo (median Hb of 75 g/L), 6 mo (Hb of 99 g/L), and 9 mo (Hb of 107 g/L) to 1 year (Hb 111 of g/L) and 2 years (Hb 117 g/L) after colostomy (Figure 2). Postoperative transfusions were conducted in 3 of 14 patients (transfusion requirements for 2 patients in other hospitals was unknown) in the colostomy group. The dynamic remission rates between the colostomy and conservative groups after surgery were as follows: 86% vs 4% at 3 mo (P < 0.001), 86% vs 12% at 6 mo (P < 0.001), 93% vs 20% at 9 mo (P < 0.001), 100% vs 24% at 1 year (P < 0.001), and 100% vs 20% at 2 years (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Case | Median(range or %) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Age | 70 | 83 | 49 | 48 | 59 | 72 | 58 | 73 | 56 | 47 | 63 | 68 | 46 | 59 | 61 (47-83) |

| Sex | F | F | F | F | F | F | M | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | 13 (F, 93%) |

| Primary cancer | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | Rectum | Cervix | Cervix | Anus | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | Cervix | 12 (Cervix, 86%) |

| Radiation dosage, Gy | 98 | 80 | 96 | 60 | 80 | 78 | 50 | 80 | 80 | 84 | 86 | 74 | 120 | 80 | 82 (50-120) |

| Duration of bleeding in mo | 19 | 15 | 14 | 21 | 15 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 13 (7-21) |

| Pre-Op transfusion (U) | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | - | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | 12 (Yes, 86%) |

| Duration of stoma in mo | 48 | 34 | 18 | 10 | 34 | 9 | 26 | 15 | 12 | 53 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 16 (9-53) | |

| Indication(s) for colostomy | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Moderate anemia + perianal pain | Severe anemia | Severe anemia + perianal pain | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia | Severe anemia+ sigmoid colon sclerosis | - |

| Hb, g/L | |||||||||||||||

| Pre-Op Hb | 44 | 36 | 76 | 63 | 36 | 35 | 71 | 87 | 52 | 78 | 72 | 78 | 76 | 78 | 63 (35-87) |

| Post-Op 3 mo | 85 | - | 85 | - | - | 45 | 87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 75 (45-87) |

| Post-Op 6 m | - | - | - | - | 94 | - | - | 77 | - | - | 108 | 118 | - | - | 99 (77-118) |

| Post-Op 9 mo | - | - | - | 102 | - | 75 | 120 | - | - | - | - | 117 | 122 | - | 107 (75-120) |

| Post-Op 1 yr | - | - | - | 100 | 113 | - | - | 123 | 114 | 114 | - | - | - | 105 | 111 (100-123) |

| Post-Op 2 yr | - | - | 118 | 102 | - | 111 | 135 | 130 | 114 | - | 110 | - | 117 | - | 117 (102-135) |

| Post-Op transfusion | No | Yes | No | No | No | yes | No | yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Stoma closure | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 (Yes, 93%) |

| Stoma complications | Hernia | - | - | - | - | - | Prolapse | - | Obstruction | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (Yes, 21%) |

| Pre-Op bleeding score | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 (2-3)1 |

| Bleeding score at stoma reversal | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 (0-1)1 |

| Treatment after stoma | - | - | - | - | - | APC 1 | Formalin 1 | APC 1 | - | - | APC 1 | - | - | - | |

Among the 14 patients with severe bleeding treated by colostomy, all obtained complete remission of bleeding during follow-up. Only 3 (23%) of 13 patients received one round of APC after stoma to control bleeding, and 1 patient received 4% formalin irrigation after colostomy (Table 2). Among the 14 patients, 13 (93%) underwent stoma closure, and the remaining patient did not undergo stoma reversal due to concerns of surgical risks because of old age (83 years old). The median duration of stoma was 16 mo (range: 9-53 mo). Stoma complications occurred in 3 (21%) cases, including 1 para-stoma hernia, 1 stoma prolapse, and 1 stoma obstruction (Grade II by Clavien-Dindo classification)[23]. All 3 patients recovered well after stoma closure.

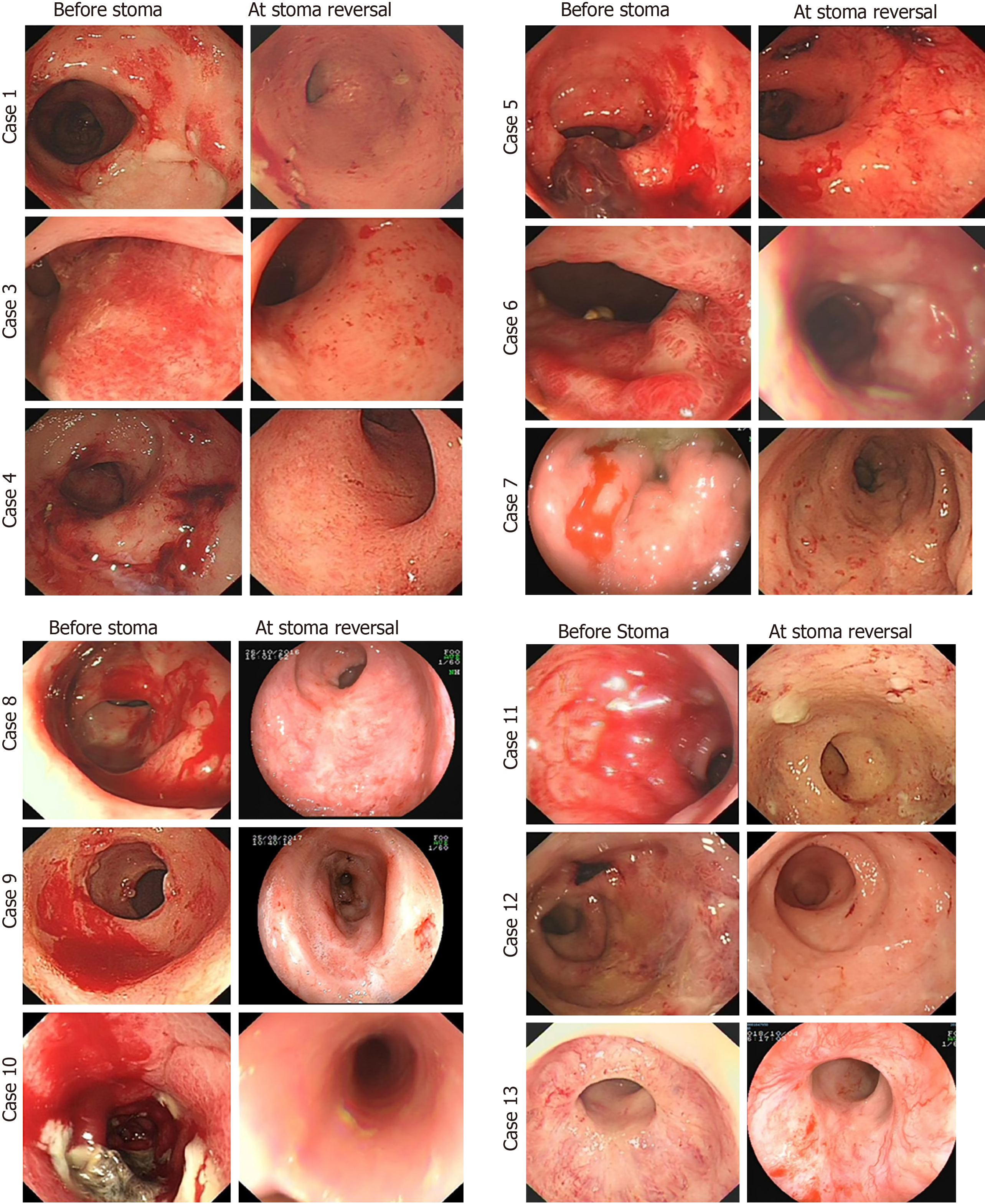

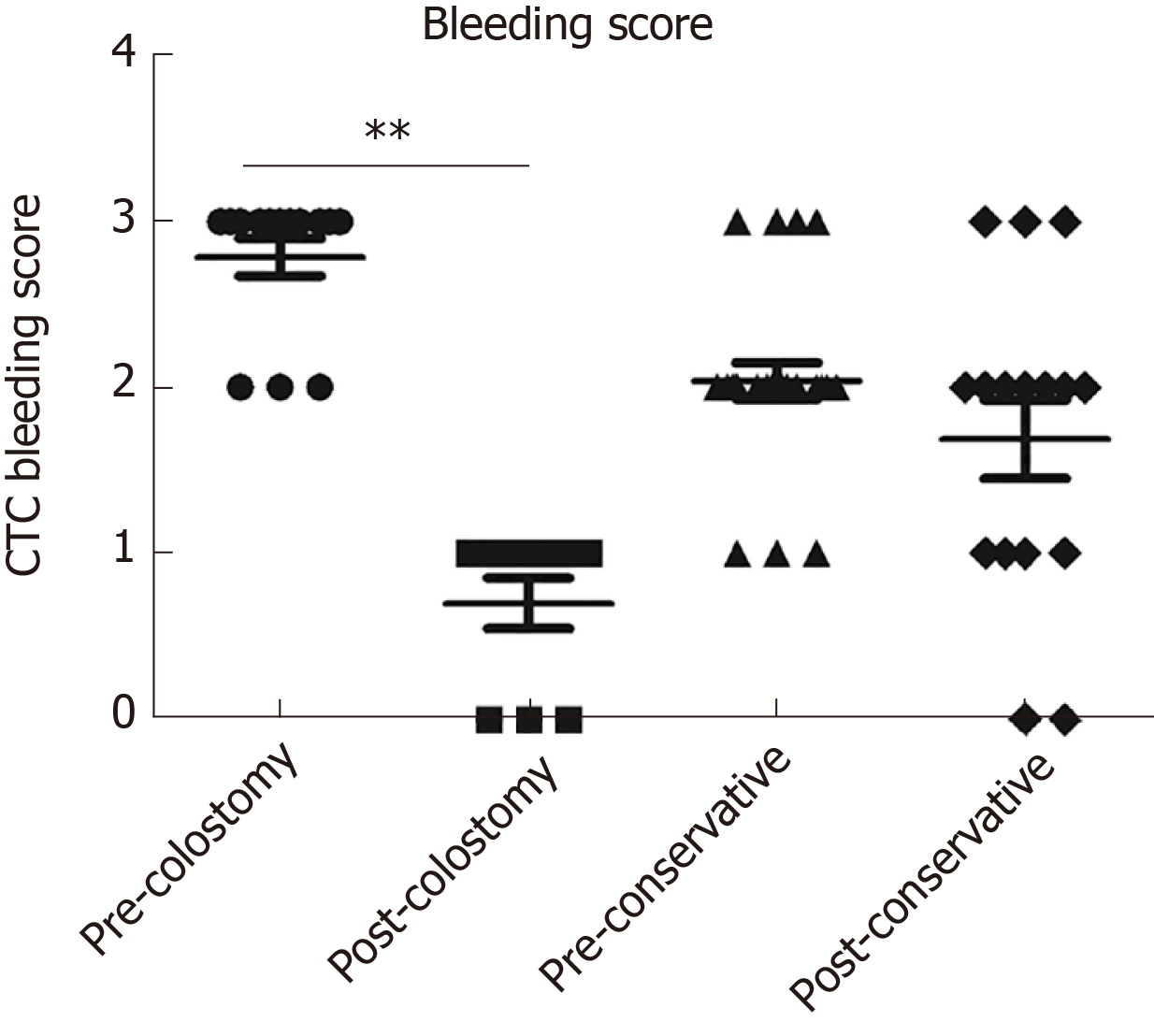

Endoscopic findings of bleeding, confluent telangiectasia, and congested mucosa improved dramatically at stoma reversal compared to before stoma creation (Figure 3). The bleeding score by CTCAE decreased from Pre-Op 2.7 points ± 0.5 points to 0.8 points ± 0.5 points (P < 0.001) at 1 year after stoma in the colostomy group; the bleeding score was 2.0 ± 0.5 at initial diagnosis and 1.7 ± 0.9 (P = 0.1282) at 1 year after treatments in the conservative group (Table 1 and Figure 4).

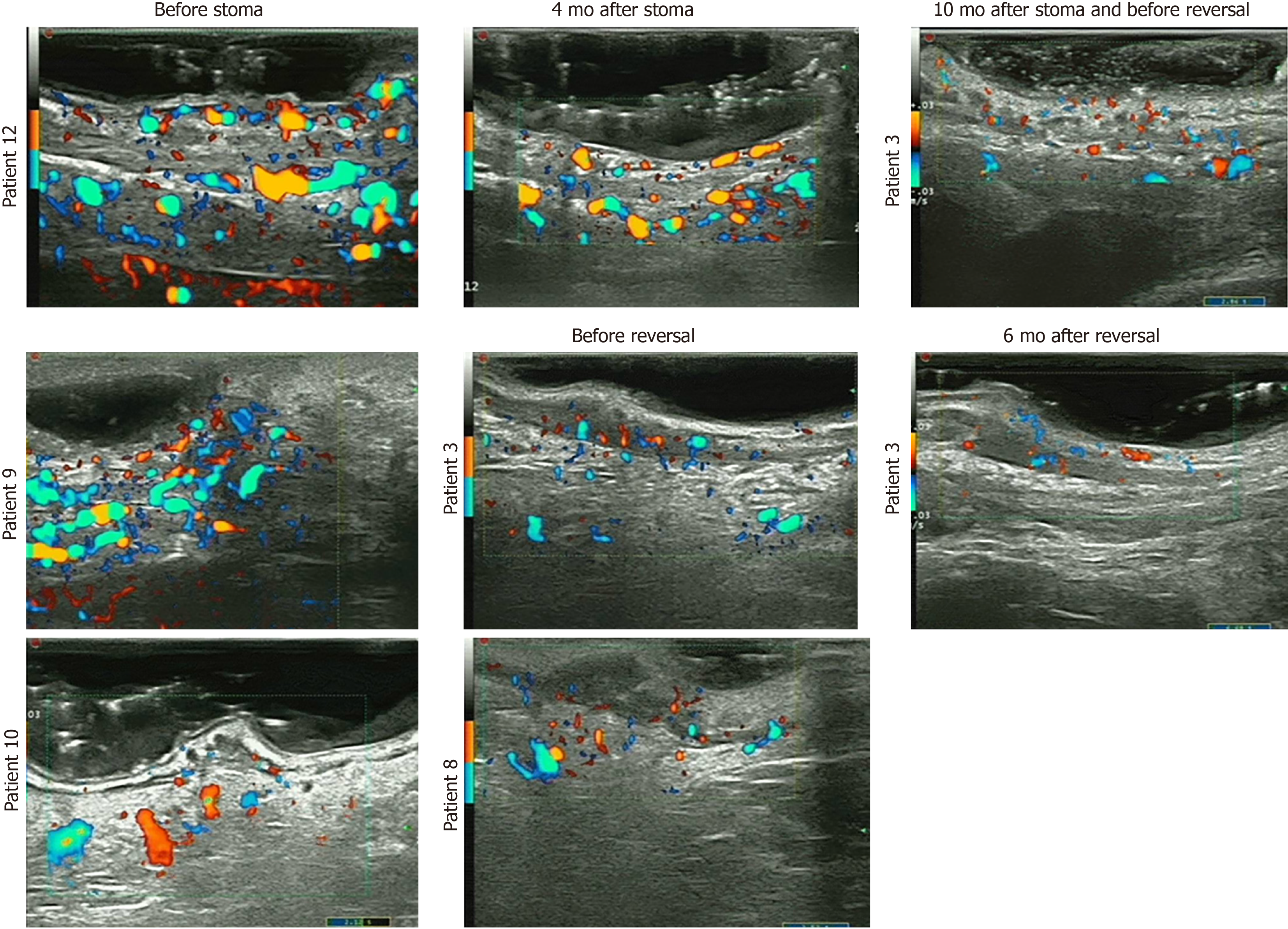

Endorectal ultrasound (EUS) was analyzed retrospectively before stoma and at reversal in 5 patients; the remaining patients did not receive EUS at either of these two time points. In our previous study, thickening of the rectal wall, blurred wall stratification, and increased vascularity were EUS features in CRP[24]. In this study, we found similar features before stoma creation and a tremendous decrease in superficial vascularity, which can explain the cessation of bleeding (Figure 5).

To evaluate the severity of the effect on the rectal wall and pelvic floor in the colostomy group, we also report magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters related to CRP, including the thickness of the rectal wall, width of the presacral space, and thicknesses of the levator ani, the gluteus maximus muscle, the obturator intemus, and the distal part of the sigmoid colon (Table 3), which was referred to in our previous study of radiation injury to the pelvis[25]. MRI scans both at pre-colostomy and at reversal were analyzed in 5 patients, as the remaining 9 did not receive MRI scans both pre-colostomy and at reversal. The thickness of the rectal wall was significantly decreased at reversal (8.91 ± 1.61) compared with pre-colostomy (10.7 ± 4.29) (P = 0.047) (Table 3).

| Variable, mm | Pre-colostomy, mean ± SD | At reversal, mean ± SD | P value, paired t-test |

| Thickness of rectal wall | 10.76 ± 4.29 | 8.91 ± 1.61 | 0.047 |

| Width of presacral space | 15.57 ± 8.86 | 15.84 ± 4.11 | 0.328 |

| Thickness of left levator ani | 2.81 ± 1.07 | 3.18 ± 1.39 | 0.341 |

| Thickness of right levator ani | 3.42 ± 1.26 | 3.45 ± 1.66 | 0.944 |

| Thickness of left gluteus maximus muscle | 31.36 ± 3.80 | 32.21 ± 9.0 | 0.769 |

| Thickness of right gluteus maximus muscle | 29.89 ± 4.19 | 32.15 ± 11.95 | 0.693 |

| Thickness of left obturator internus | 15.16 ± 1.97 | 17.89 ± 1.77 | 0.160 |

| Thickness of right obturator internus | 13.79 ± 4.90 | 14.36 ± 5.50 | 0.060 |

| Thickness of distal part of sigmoid colon | 4.50 ± 0.73 | 5.08 ± 1.17 | 0.503 |

Anorectal functions before stoma and after reversal were evaluated by CRPSS scores in all 12 patients in the colostomy group. The results showed that rectal bleeding, peritoneal pain, tenesmus, urgency and fecal/gas incontinency were significantly improved after stoma reversal compared to those before stoma creation. Additionally, all of these scores were < 2 points, which indicated that anorectal function recovered very well after stoma reversal (Figure 6). Complete remission of bleeding and good performance of anorectal function compared to the normal population (scores ≤ 1 point) were observed. We also analyzed anorectal manometry to objectively assess anorectal function before reversal in 6 of the 14 patients who received it. Increased sensitivity of the rectal mucosa and decreased rectal volume were observed. Decreased sphincter functions were found in 2 of 6 cases (Table 4). These patients fulfilled the indications for reversal, and we found that these patients obtained good performance of anorectal function after reversal. Rectal defecography was also conducted before reversal, and no stricture was observed.

| Patient | Tensity of anorectal ring | Function of contraction | Diagnosis | Sensitivity of rectal mucosa | Rectal volume | Repression of anorectum reflex | Anal relaxation when simulating defecation |

| 1 | Increase | Good | Internal sphincter spasm | Increase | Normal | Normal | Good |

| 4 | Increase | Good | - | Normal | Decrease | Normal | Good |

| 6 | Decrease | Decrease | Decreased sphincter function | Increase | Decrease | Normal | Good |

| 9 | Normal | Decrease | Decreased sphincter function | Increase | Decrease | Abnormal | Good |

| 12 | Normal | Decrease | - | Increase | Decrease | Good | |

| 14 | Normal | Good | - | Increase | Decrease | Abnormal | Good |

QOL after stoma was assessed in the colostomy and conservative groups using EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires. As there are no similar reports in the Chinese population, we referred to the normal German population[26]. Osoba et al[26] suggested that a difference of ≥ 20 points in global health was considered to be clinically relevant. In the panel of patients who underwent stoma closure, QOL was dramatically improved compared to Pre-Op baseline QOL before stoma creation, including improved global health (difference of 40, P < 0.001), physical function (difference of 36.4, P < 0.001), role function (difference of 55, P < 0.001), emotional function (difference of 39.4, P < 0.001), social function (difference of 36.3, P < 0.001), and improved symptoms, such as fatigue (difference of -62.5, P < 0.001), pain (difference of -34.9, P < 0.001), dyspnea (difference of -37.8, P < 0.001), insomnia (difference of -36.2, P < 0.001), diarrhea (difference of -23.8, P < 0.001), and financial problems (difference of -35.5, P < 0.001). However, in the conservative group, no improved QOL variables with a difference of ≥ 20 were observed (Table 5). QOL after stoma closure was also compared to the normal population reference, with similar scores for functions and symptoms (Table 5).

| QLQ-C30 scale | Reference: Normal German population | Colostomy group, n = 14, mean ± SD | Conservative group, n = 25, mean ± SD | ||||||

| Pretreat-ment | Follow-up | Δ(FU)-Pre2 | Signifi-cance1 | Pretreat-ment | Follow-up | Δ(FU)-Pre | Signifi-cance1 | ||

| Global health | 63.2 | 23.1 ± 15.1 | 63.1 ± 18.3 | 40 | < 0.001 | 47.1 ± 21.5 | 62.3 ± 25.0 | 15.2 | 0.033 |

| Physical function | 82.6 | 50.7 ± 17.8 | 87.1 ± 13.7 | 36.4 | < 0.001 | 78.0 ± 22.7 | 78.6 ± 26.1 | 0.6 | 0.856 |

| Role function | 75 | 34.3 ± 23.9 | 89.3 ± 20.5 | 55 | < 0.001 | 77.5 ± 24.9 | 77.5 ± 29.1 | 0 | 0.775 |

| Emotional function | 62.2 | 46.3 ± 27.4 | 85.7 ± 14.9 | 39.4 | < 0.001 | 75.7 ± 17.6 | 80.8 ± 23.8 | 5.1 | 0.384 |

| Cognition function | 81.3 | 92.6 ± 12.7 | 95.2 ± 9.8 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 94.2 ± 15.6 | 95.7 ± 9.0 | 1.5 | 0.798 |

| Social function | 78.4 | 43.5 ± 28.9 | 79.8 ± 18.0 | 36.3 | < 0.001 | 91.3 ± 20.6 | 89.1 ± 21.1 | -2.2 | 0.916 |

| Fatigue | 34.1 | 72.8 ± 12.9 | 10.3 ± 18.5 | -62.5 | < 0.001 | 26.6 ± 24.1 | 23.2 ± 27.2 | -3.4 | 0.695 |

| Nausea/ vomiting | 5.7 | 4.6 ± 15.5 | 0 ± 0 | -4.6 | - | 5.1 ± 15.4 | 6.5 ± 16.5 | 1.4 | 0.655 |

| Pain | 33.1 | 44.4 ± 28.3 | 9.5 ± 15.1 | -34.9 | < 0.001 | 14.5 ± 21.5 | 11.6 ± 18.4 | -2.9 | 0.481 |

| Dyspnea | 18.8 | 42.6 ± 31.0 | 4.8 ± 11.7 | -37.8 | < 0.001 | 14.5 ± 19.7 | 8.7 ± 18.0 | -5.8 | 0.210 |

| Insomnia | 38.5 | 48.1 ± 35.5 | 11.9 ± 20.3 | -36.2 | < 0.001 | 21.7 ± 21.6 | 26.1 ± 31.7 | 4.4 | 0.287 |

| Appetite loss | 9.4 | 22.2 ± 27.2 | 0 ± 0 | -22.2 | - | 10.1 ± 25.5 | 8.7 ± 18.0 | -1.4 | 0.785 |

| Constipation | 9.1 | 9.3 ± 14.9 | 9.5 ± 15.1 | -0.2 | 1.0 | 8.7 ± 20.6 | 7.2 ± 22.4 | -1.5 | 0.414 |

| Diarrhea | 9.2 | 33.3 ± 33.3 | 9.5 ± 26.5 | -23.8 | < 0.001 | 11.6 ± 23.8 | 2.9 ± 9.6 | -8.7 | 0.078 |

| Financial difficulties | 17.1 | 59.3 ± 26.2 | 23.8 ± 31.9 | -35.5 | < 0.001 | 26.1 ± 31.7 | 24.6 ± 30.5 | -1.5 | 0.595 |

The literature reports that 1%-6% of CRP patients have transfusion-dependent bleeding; many of these cases can be treated with topical formalin, APC, or hyperbaric oxygen treatment[1]. Surgical resection of rectal lesions is usually reserved as the last resort for hemorrhagic CRP because it is associated with high morbidity and mortality[3,13,19]. In our previous study, fecal diversion was found to be a simple, effective, and safe procedure for severe hemorrhagic CRP[16]. Theoretically, fecal diversion can reduce the irritation of stool and accelerate the course of fibrosis and thus relieve CRP bleeding rapidly[16].

In this study, we report results for diverting colostomy and conservative treatments of enemas, topical formalin, or APC in a large cohort of patients with severe hemorrhagic CRP and who were followed for at least 1 year. The results showed that stomas can be reversed in 93% of CRP cases with severe hemorrhage. Increased Hb and rapid cessation of bleeding were found in the colostomy group, whereas bleeding and Hb levels were not changed in the conservative group. Moreover, anorectal function was greatly improved after stoma reversal than before stoma creation, reaching the levels of the normal population. In addition, it is important to note that colostomy was performed in a very select population of CRP patients and those patients with CRP stricture and ulcerations were excluded. Stoma complications occurred in 21% of cases, including 1 case of parastomal hernia due to a weakened abdominal wall of the parastomal zone, 1 case of stoma prolapse due to an intestine overly pulled at stoma creation, and 1 case of stoma obstruction due to stricture. All of these complications were recovered after stoma reversal. According to the literature, the complication rate of stoma is approximately 20%-50%, and the complication rate of stoma in this study is thus acceptable. Thus, colostomy is a better option and can bring more benefits to CRP patients with severe bleeding than can conservative treatments.

In our previous study, we found complete remission of telangiectasia and edema, recovery of mucosal integrity, and massive fibrosis in the submucosa at 3-4 years after diversion[16]. In this study, anorectal manometry was conducted in some stoma patients and resulted in good compliance, resting pressure, and contraction. Rectal defecography was performed at reversal for all colostomy patients, and no rectal stricture was found. Thus, temporary diverting colostomy and reversal at an appropriate time can be a useful option for these patients.

In this study, most patients in the colostomy group presented with severe anemia and needed multiple transfusions. One patient did not receive transfusion, with an Hb level of 78, before colostomy. In China, blood supply is limited, and transfusion is only conducted in large central hospitals when Hb is < 60. At 3 to 6 mo after diverting colostomy, bleeding gradually remitted and increased Hb levels were observed. By 9 mo to 1 year after colostomy, most patients achieved complete remission of bleeding and the Hb level had almost returned to normal. Stoma reversal was conducted at 1 year after colostomy in 4 (31%) of 13 patients. In 5 cases, reversal was performed at more than 2 years after colostomy because the patients did not know colostomy could be reversed until we contacted them via telephone for follow-up. Thus, the median duration of stoma was prolonged to 16 mo. In fact, most stomas in this cohort could be reversed at 1 year after colostomy.

Based on the results of our retrospective study[16], we started a prospective clinical trial to enroll severe hemorrhagic CRP patients who are suitable for diverting colostomy (Clinical Trial No. NCT03397901). All patients were followed and evaluated for stoma closure for 1 year after colostomy. The indication for diverting colostomy was extended to hemorrhagic CRP with moderate anemia in our series because preventative colostomy can relieve refractory bleeding before it progresses to severe life-threatening anemia and patients can obtain dramatic benefit from preventative fecal diversion.

To date, it is still unclear whether anorectal function can be preserved after stoma closure. In this study, we found that anorectal functions, including anal control and release of gas/stool, could be restored, which also indicated that CRP was inactive after a period of diverting colostomy. Although increased rectal sensitivity and decreased rectal volume were observed at reversal by anorectal manometry, good anorectal function was achieved after reversal compared to the normal population and improved compared to that before stoma creation. No additional pelvic biofeedback treatments were required in these patients.

For some patients, an additional one to two rounds of APC were required to help control bleeding during the first 6 mo after colostomy. The temporary stoma not only enabled the remission of anal symptoms but also restored the biological functions of the anus, providing evidence to support fecal diversion as a helpful option for severe hemorrhagic CRP patients.

In some studies, bile acid malabsorption and small bowel bacterial overgrowth have been thought to be the cause of diarrhea during acute and chronic radiation enteritis[1]. Diverting colostomy cannot reverse these changes. We focused on hemorrhage in CRP and diarrhea, common in small-bowel radiation injury, which is different from tenesmus and is not the major symptom in most CRP cases.

According to our previous study, severe hemorrhagic CRP patients usually experience poor global health and fatigue due to moderate to severe anemia[16]. Their social and emotional functions are also impacted by frequent stool and anxiety of bleeding. They cannot attend social activities due to concern of looking for a lavatory[1]. In this study, after the remission of anal symptoms, we found that patients had good QOL, especially after stoma reversal, and were able to return to almost the same life as the normal population.

Anorectal functions scored by the CRPSS were assessed before stoma and after reversal. We also analyzed EUS and pelvic MRI before stoma and at reversal to evaluate the severity of CRP. To objectively evaluate anorectal function before reversal, anorectal manometry was performed and retrospectively analyzed in some patients, though only in 6 patients because manometry is not a routine test before stoma reversal.

This study presents our serial results of diverting colostomy for severe hemorrhagic CRP. The results showed significant superiority over conservative treatments. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, this study was retrospective, with potential recall bias. Second, the sample size of this cohort was relatively small, which will affect the grade of evidence, and a larger cohort is essential. Finally, EUS, MRI, and anorectal manometry were only performed on patients undergoing colostomy reversal as a limitation. Thus, we started a prospective cohort of diverting colostomy for severe hemorrhagic CRP and will provide more reliable evidence in the future.

In conclusion, diverting colostomy is a very effective and rapid method for the remission of severe bleeding in CRP patients. The stoma can be reversed and good anorectal function can be restored after reversal in most patients.

Chronic radiation proctopathy (CRP) is a common and sometimes difficult issue after radiotherapy for pelvic malignancies. Severe and refractory bleeding is hard to manage. Diverting fecal diversion is very effective and fast in remission of rectal bleeding in the management of severe CRP bleeding in our previous study, but diverting stoma is usually thought to be permanent according to the literature. The anorectal function and quality of life after stoma reversal remain unclear.

During the past 3 years, we have successfully performed colostomy reversals in a larger cohort of CRP patients with severe bleeding and followed patients after colostomy reversals. In this series study, we will report the efficacy of colostomy, the rate of stoma closure of diverting colostomy, and anorectal function after reversals.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of colostomy and the rate of stoma reversals in severe hemorrhagic CRP.

Patients with severe hemorrhagic CRP who underwent colostomy or conservative treatment were enrolled retrospectively. Rectal bleeding, hemoglobin (Hb), endoscopic features, endo-ultrasound (EUS), rectal manometry, and MRI scans were recorded. Anorectal functions and quality of life before stoma and after stoma reversal were scored with EORTC-QOL-C30 questionnaires.

After screening 738 continual CRP patients, 14 patients in the colostomy group and 25 patients in the conservative group as controls were enrolled. The Hb was gradually increased to normal levels in two years after colostomy, while no significant increase was observed in the conservative group. All of 14 patients obtained complete remission of bleeding and colostomy was successfully reversed in 13 of 14 (93%), except one with very old age. Improved endoscopic telangiectasia and bleeding, decreased vascularity by EUS, increased presarcal space, and thickened rectal wall by MRI were observed. Anorectal functions and quality of life were significantly improved after stoma reverse.

Diverting colostomy is a very effective method in the remission of refractory hemorrhagic CRP. Meanwhile, stoma can be reversed and anorectal functions can be recovered after reversal.

Preventative diverting colostomy can relieve refractory bleeding before it progresses to severe life-threatening anemia and patients can obtain dramatic benefit. Thus, we have started a prospective clinical trial to enroll severe hemorrhagic CRP patients who are suitable for diverting colostomy (Clinical Trial No. NCT03397901), which will provide more evidence to the usage of colostomy in severe CRP patients.

We thank Dr. Jervoise Andreyev (a famous international leader in radiation proctitis, Consultant Gastroenterologist in Pelvic Radiation Disease, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London SW3 6JJ, United Kingdom) for critical revisions of our paper.

| 1. | Andreyev J. Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a new understanding to improve management of symptomatic patients. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1007-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leiper K, Morris AI. Treatment of radiation proctitis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2007;19:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Pironi D, Panarese A, Vendettuoli M, Pontone S, Candioli S, Manigrasso A, De Cristofaro F, Filippini A. Chronic radiation-induced proctitis: the 4 % formalin application as non-surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sahakitrungruang C, Thum-Umnuaysuk S, Patiwongpaisarn A, Atittharnsakul P, Rojanasakul A. A novel treatment for haemorrhagic radiation proctitis using colonic irrigation and oral antibiotic administration. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e79-e82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kochhar R, Sharma SC, Gupta BB, Mehta SK. Rectal sucralfate in radiation proctitis. Lancet. 1988;2:400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kochhar R, Patel F, Dhar A, Sharma SC, Ayyagari S, Aggarwal R, Goenka MK, Gupta BD, Mehta SK. Radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis. Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of oral sulfasalazine plus rectal steroids versus rectal sucralfate. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim TO, Song GA, Lee SM, Kim GH, Heo J, Kang DH, Cho M. Rebampide enema therapy as a treatment for patients with chronic radiation proctitis: initial treatment or when other methods of conservative management have failed. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:629-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kwan V, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Gillespie PE, Murray MA, Kaffes AJ, Henriquez MS, Chan RO. Argon plasma coagulation in the management of symptomatic gastrointestinal vascular lesions: experience in 100 consecutive patients with long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:58-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Parikh S, Hughes C, Salvati EP, Eisenstat T, Oliver G, Chinn B, Notaro J. Treatment of hemorrhagic radiation proctitis with 4 percent formalin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:596-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sahakitrungruang C, Patiwongpaisarn A, Kanjanasilp P, Malakorn S, Atittharnsakul P. A randomized controlled trial comparing colonic irrigation and oral antibiotics administration versus 4% formalin application for treatment of hemorrhagic radiation proctitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1053-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Haas EM, Bailey HR, Faragher I. Application of 10 percent formalin for the treatment of radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:213-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cullen SN, Frenz M, Mee A. Treatment of haemorrhagic radiation-induced proctopathy using small volume topical formalin instillation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1575-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rustagi T, Corbett FS, Mashimo H. Treatment of chronic radiation proctopathy with radiofrequency ablation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:428-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Glover M, Smerdon GR, Andreyev HJ, Benton BE, Bothma P, Firth O, Gothard L, Harrison J, Ignatescu M, Laden G, Martin S, Maynard L, McCann D, Penny CEL, Phillips S, Sharp G, Yarnold J. Hyperbaric oxygen for patients with chronic bowel dysfunction after pelvic radiotherapy (HOT2): a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:224-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hayne D, Smith AE. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment of chronic refractory radiation proctitis: a randomized and controlled double-blind crossover trial with long-term follow-up: in regard to Clarke et al. (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008 Mar 12). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1621; author reply 1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yuan ZX, Ma TH, Wang HM, Zhong QH, Yu XH, Qin QY, Wang JP, Wang L. Colostomy is a simple and effective procedure for severe chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5598-5608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma TH, Yuan ZX, Zhong QH, Wang HM, Qin QY, Chen XX, Wang JP, Wang L. Formalin irrigation for hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3593-3598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Photopulos GJ, Jones RW, Walton LA, Fowler WC. A simplified method of complete diversionary colostomy for patients with radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis. Gynecol Oncol. 1977;5:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anseline PF, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Radiation injury of the rectum: evaluation of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1981;194:716-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ayerdi J, Moinuddeen K, Loving A, Wiseman J, Deshmukh N. Diverting loop colostomy for the treatment of refractory gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis. Mil Med. 2001;166:1091-1093. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11936] [Article Influence: 361.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yuan ZX, Ma TH, Zhong QH, Wang HM, Yu XH, Qin QY, Chu LL, Wang L, Wang JP. Novel and Effective Almagate Enema for Hemorrhagic Chronic Radiation Proctitis and Risk Factors for Fistula Development. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:631-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9233] [Article Influence: 543.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Cao F, Ma TH, Liu GJ, Wen YL, Wang HM, Kuang YY, Qin S, Liu XY, Huang BJ, Wang L. Correlation between Disease Activity and Endorectal Ultrasound Findings of Chronic Radiation Proctitis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:2182-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ma T, Zhong Q, Cao W, Qin Q, Meng X, Wang H, Wang J, Wang L. Clinical Anastomotic Leakage After Rectal Cancer Resection Can Be Predicted by Pelvic Anatomic Features on Preoperative MRI Scans: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:1326-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2281] [Cited by in RCA: 2443] [Article Influence: 87.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Taira K, Gavriilidis P S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ