Published online Sep 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i36.5508

Peer-review started: May 12, 2020

First decision: May 29, 2020

Revised: June 10, 2020

Accepted: August 29, 2020

Article in press: August 29, 2020

Published online: September 28, 2020

Processing time: 134 Days and 19.8 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is a heavy burden in China. Nutritional support for GC patients is closely related to postoperative rehabilitation. However, the role of early oral feeding after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in GC patients is unclear and high-quality research evidence is scarce.

To prospectively explore the safety, feasibility and short-term clinical outcomes of early oral feeding after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy for GC patients.

This study was a prospective cohort study conducted between January 2018 and December 2019 based in a high-volume tertiary hospital in China. A total of 206 patients who underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy for GC were enrolled. Of which, 105 patients were given early oral feeding (EOF group) after surgery, and the other 101 patients were given the traditional feeding strategy (control group) after surgery. Perioperative clinical data were recorded and analyzed. The primary endpoints were gastrointestinal function recovery time and postoperative complications, and the secondary endpoints were postoperative nutritional status, length of hospital stay and expenses, etc.

Compared with the control group, patients in the EOF group had a significantly shorter postoperative first exhaust time (2.48 ± 1.17 d vs 3.37 ± 1.42 d, P = 0.001) and first defecation time (3.83 ± 2.41 d vs 5.32 ± 2.70 d, P = 0. 004). In addition, the EOF group had a significant shorter postoperative hospitalization duration (5.85 ± 1.53 d vs 7.71 ± 1.56 d, P < 0.001) and lower postoperative hospitalization expenses (16.60 ± 5.10 K¥ vs 21.00 ± 7.50 K¥, P = 0.014). On the 5th day after surgery, serum prealbumin level (214.52 ± 22.47 mg/L vs 204.17 ± 20.62 mg/L, P = 0.018), serum gastrin level (246.30 ± 57.10 ng/L vs 223.60 ± 55.70 ng/L, P = 0.001) and serum motilin level (424.60 ± 68.30 ng/L vs 409.30 ± 61.70 ng/L, P = 0.002) were higher in the EOF group. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of total postoperative complications between the two groups (P = 0.507).

Early oral feeding after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy can promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function, improve postoperative nutritional status, reduce length of hospital stay and expenses while not increasing the incidence of related complications, which indicates its safety, feasibility and potential benefits for gastric cancer patients.

Core Tip: The role of early oral feeding (EOF) after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer (GC) is unclear. In this prospective cohort study, we focus on the safety, feasibility and short-term outcomes of EOF in GC patients. Our results showed that EOF promoted the recovery of gastrointestinal function, improved postoperative nutritional status, reduced length of hospital stay and expenses while not increasing the incidence of related complications, which indicated the safety, feasibility and potential benefits of EOF for GC patients.

- Citation: Lu YX, Wang YJ, Xie TY, Li S, Wu D, Li XG, Song QY, Wang LP, Guan D, Wang XX. Effects of early oral feeding after radical total gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(36): 5508-5519

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i36/5508.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i36.5508

Gastric cancer (GC) represents one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide with the highest incidence rate in Eastern Asia[1]. In China, GC was the second most prevalent cancer and had the second highest mortality rate in 2015[2]. At present, surgery is still the core procedure of comprehensive treatment for locally advanced GC. Some studies showed that patients who underwent gastrectomy could be supported by early enteral nutrition after surgery, and early postoperative oral feeding had advantages in promoting gastrointestinal function recovery and nutritional improvement of patients[3-5]. Similar recommendations were also given by the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) guidelines[6]. In addition, early postoperative oral feeding has been included in the program of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery or Fast Tract Surgery, which consists of more than 20 procedures and involves colorectal cancer[7], GC[8], lung cancer[9], liver cancer[10], gynecological surgery[11], etc. The stomach is located in the upper digestive tract, and radical total gastrectomy is one of the most complicated operations in the department of gastrointestinal surgery.

So far, the safety and feasibility of early oral feeding (EOF) after radical total gastrectomy in GC patients is still disputed, and high-quality research evidence is scarce. According to a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) study from Japan, EOF may bring potential benefits to total gastrectomy patients, but the conclusion needs to be further verified due to the insufficient sample size[12]. Although some studies have also been carried out in China[13-15], most of them were retrospective observational studies. Few studies focus on patients undergoing laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy. Therefore, a prospective cohort study was designed in our center. The objective was to investigate the safety, feasibility and short-term outcomes of EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in patients with GC.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital. In order to study the safety, feasibility and short-term outcomes of EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in GC patients, a prospective, cohort study was designed and conducted in Chinese PLA General Hospital between January 2018 and December 2019. Patients were enrolled prospectively and were allocated to the EOF group or traditional feeding group (control group). After operation, patients were given the same intervention measures except for a different dietary schedule. All patients were followed up for 1-3 mo.

GC patients who underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy between January 2018 and December 2019 in the First Medical Center of PLA General Hospital were enrolled.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged 18-79 years; (2) GC confirmed by gastroscopy and biopsy; (3) No distant metastasis were found in preoperative examination and intraoperative probes, and tumor TNM stage belonged to stage I-III; (4) The American Society of Anesthesiologists class I-II; and (5) Patients who underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Emergency operations, such as GC with hemorrhage, perforation and other serious complications; (2) Gastric stump cancer; (3) Other concurrent malignant tumors; (4) Diabetes or other serious metabolic diseases; (5) Severe malnutrition; (6) History of abdominal surgery; (7) preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or target therapy; (8) Combined thoracotomy or thoracoscopic surgery; (9) Conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery; (10) Time of operation longer than 5 h; (11) Intraoperative blood loss greater than 800 mL and transfusion; (12) Postoperative pathology confirmed non-R0-resection; and (13) Patients transferred to Intensive Care Unit after surgery.

Finally, 206 patients were recruited in this study. Of which, 105 patients were given EOF after surgery (EOF group), and the other 101 patients were given the traditional feeding strategy after surgery (control group).

All patients underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in the department of general surgery and preoperative informed consent was obtained. The procedure used was: (1) The nasogastric tube was placed 2 h before surgery or immediately after general anesthesia and was usually removed at the end of operation; (2) All patients were given general anesthesia through endotracheal intubation; (3) Radical total gastrectomy and perigastric lymph node dissection were performed in accordance with the Japanese GC treatment guidelines 2014 (version 4)[16]; (4) laparoscopic surgery was performed with the 5-holes method[17]; and (5) Abdominal drainage tube was not routinely placed during the operation, and it was removed at early stage after operation if placed.

After the operation, two groups were given the same intervention measures except for different dietary strategies.

(1) Early oral feeding group (EOF group): On the day of surgery, drinking warm water was encouraged. On the 1st day after surgery, patients were instructed to drink water, a small amount of clear fluid diet and enteral nutrition preparation (TP powder, Ensure®, Abbott). Then, the diet was gradually changed to liquid diet, semi-liquid diet and finally soft food. The energy balance was supplemented by intravenous nutrition. The dietary protocol of the EOF group was shown in Table 1.

| Time point | Protocol |

| Day of surgery | Attempt to drink warm water (< 50 mL/h) 6 h after surgery was encouraged |

| Postoperative day 1 | Total oral fluid intake increased up to 500 mL, enteral nutrition preparation was given |

| Postoperative day 2 | Total oral fluid intake increased up to 1000 mL, liquid diet (such as small amounts of rice soup) started |

| Postoperative day 3 | Total oral fluid intake increased up to 1500 mL gradually, intravenous fluid volume gradually reduced |

| Postoperative day 4 | Frequent small amounts of oral fluids, small amounts of semi-liquid foods (such as porridge, noodles or other soft foods), intravenous fluids stopped if possible |

| Postoperative day 5 | Frequent small amounts of oral fluids with gradual transition to total semi-liquid diet and soft foods |

(2) Traditional feeding group (control group): Routine postoperative fasting was performed in all patients. After the first exhaust or defecation, patients were given oral feeding gradually. The diet was gradually changed from water, clear fluid diet to liquid diet, semi-liquid diet and finally soft food. The energy balance was supplemented by intravenous nutrition. Detailed energy requirements were calculated according to ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery[18].

In addition, the same discharge standards were implemented in both groups: (1) Abdominal drainage tube had been removed; (2) Gastrointestinal function had been restored; (3) No fluid therapy; (4) Solid or semi-solid foods were tolerable, and oral feeding could provide more than 60% of the patient’s energy requirements; (5) No fever; (6) Wound healing well; and (7) Patients could move freely and agreed to be discharged. All patients were followed up for 1-3 mo by outpatient consultation or telephone after discharge.

The following data were collected: Gastrointestinal function recovery time (first exhaust time and first defecation time); postoperative hospitalization duration and expenses; postoperative nutritional status (serum prealbumin level and serum albumin level) and postoperative gastrointestinal hormone level (gastrin and motilin level); tolerance of oral feeding after surgery (abdominal distension, postoperative nausea, reinsertion of nasogastric tube); postoperative complications (anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic or duodenal stump fistula, wound infection, postoperative ileus, postoperative pneumonia, etc.).

SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) was used for statistical analysis in this study. For quantitative data, the mean ± standard deviation was calculated, and Student's t-test, analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U-test or paired t test was chosen appropriately for comparison of differences between groups. For categorical data, differences between groups were evaluated using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed using logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between the EOF group and control group in gender, age, body mass index, NRS-2002 score, preoperative serum prealbumin (PALB) and albumin (ALB) levels, preoperative serum gastrin and motilin levels, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, tumor node metastasis stage, tumor differentiation, Borrmann classification and Lauren classification (Table 2).

| Baseline data | EOF group, n = 105 | Control group, n = 101 | t value | P value |

| Gender, male/female, n | 88/17 | 86/15 | 0.005 | 0.942 |

| Age, yr | 61.69 ± 10.80 | 61.36 ± 11.72 | 1.387 | 0.167 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.86 ± 4.70 | 23.15 ± 4.32 | -0.797 | 0.426 |

| NRS-2002 score , < 3 or ≥ 3, n | 41/64 | 38/63 | 0.034 | 0.872 |

| Preoperative serum PALB, mg/L | 227.50 ± 28.20 | 225.41 ± 23.60 | 1.269 | 0.264 |

| Preoperative serum ALB, g/L | 39.24 ± 4.36 | 38.58 ± 3.85 | 1.833 | 0.076 |

| Preoperative serum gastrin, ng/L | 212.40 ± 57.50 | 211.70 ± 53.80 | 1.512 | 0.134 |

| Preoperative serum motilin, ng/L | 358.40 ± 67.10 | 360.20 ± 68.70 | -1.946 | 0.071 |

| Operating time, min | 228.70 ± 31.20 | 225.90 ± 29.47 | 1.228 | 0.219 |

| Blood loss, mL | 155.68 ± 51.35 | 152.85 ± 52.46 | 1.294 | 0.211 |

| Pathological stage, n (%) | 0.014 | 0.913 | ||

| Stage I | 13 (12.38) | 11 (10.89) | ||

| Stage II | 48 (45.71) | 45 (44.55) | ||

| Stage III | 44 (41.91) | 45 (44.55) | ||

| Differentiation, n (%) | 0.008 | 0.930 | ||

| Poor | 52 (49.52) | 33 (49.25) | ||

| Moderate | 36 (34.29) | 23 (34.33) | ||

| Well | 17 (16.19) | 11 (16.42) | ||

| Borrmann types, n (%) | 0.221 | 0.694 | ||

| I | 8 (7.62) | 9 (8.91) | ||

| II | 34 (32.38) | 33 (32.67) | ||

| III | 47 (44.76) | 45 (44.56) | ||

| IV | 16 (15.24) | 14 (13.86) | ||

| Lauren types, n (%) | 0.675 | 0.407 | ||

| Intestinal type | 81 (77.14) | 74 (73.27) | ||

| Diffuse type | 24 (22.86) | 27 (26.73) |

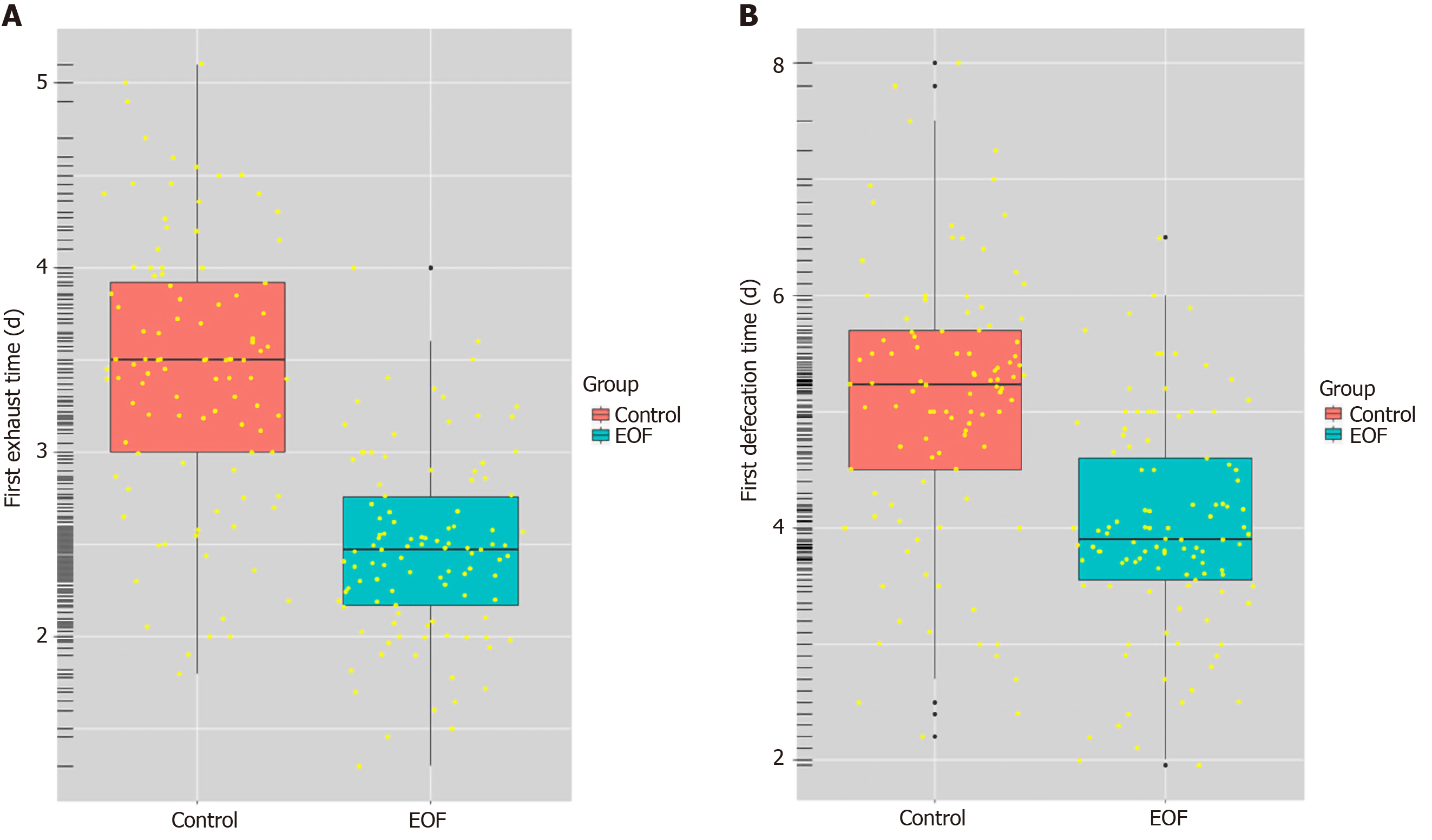

Compared with the control group, the EOF group had a shorter first postoperative exhaust time (2.48 ± 1.17 d vs 3.37 ± 1.42 d) and first defecation time (3.83 ± 2.41 d vs 5.32 ± 2.70 d), and the differences were both significant P = 0.001, P = 0.004, respectively) (Table 3, Figure 1).

| Group | EOF group, n = 105 | Control group, n = 101 | t value | P value |

| Postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery | ||||

| First exhaust time, d | 2.48 ± 1.17 | 3.37 ± 1.42 | -63;4.46 | 0.001 |

| First defecation time, d | 3.83 ± 2.41 | 5.32 ± 2.70 | -63;3.76 | 0.004 |

| Postoperative hospitalization and expenses | ||||

| Postoperative hospital stay, d | 5.85 ± 1.53 | 7.71 ± 1.56 | -63;5.32 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization expenses, K¥ | 16.60 ± 5.10 | 21.00 ± 7.50 | -63;3.55 | 0.014 |

| Postoperative nutritional status on the 5th day after surgery | ||||

| Postoperative PALB, mg/L | 214.52 ± 22.47 | 204.17 ± 20.62 | 2.85 | 0.018 |

| Postoperative ALB, g/L | 36.24 ± 5.93 | 35.16 ± 4.78 | 1.744 | 0.079 |

| Postoperative gastrointestinal hormone level on the 5th day after surgery | ||||

| Postoperative serum gastrin, ng/L | 246.30 ± 57.10 | 223.60 ± 55.70 | 7.405 | 0.001 |

| Postoperative serum motilin, ng/L | 424.60 ± 68.30 | 409.30 ± 61.70 | 6.946 | 0.002 |

| Tolerance of oral feeding after surgery | ||||

| Abdominal distension | 8 | 6 | ||

| Postoperative nausea | 10 | 9 | ||

| Reinsertion of nasogastric tube1 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Total, % | 22 (20.95) | 18 (17.82) | 0.664 | 0.507 |

Compared with the control group, the EOF group had a shorter postoperative hospital stay (5.85 ± 1.53 d vs 7.71 ± 1.56 d) and fewer postoperative expenses (16.60 ± 5.10 K¥ vs 21.00 ± 7.50 K¥), and the differences were both significant (P < 0.001, P = 0.014, respectively) (Table 3).

Compared with the control group, the EOF group had a higher serum PALB level (214.52 ± 22.47 mg/L vs 204.17 ± 20.62 mg/L, P = 0.018). Notably, the differences in serum ALB level between the EOF group and the control group (36.24 ± 5.93 g/L vs 35.16 ± 4.78 g/L, P = 0.079) were not significant (Table 3).

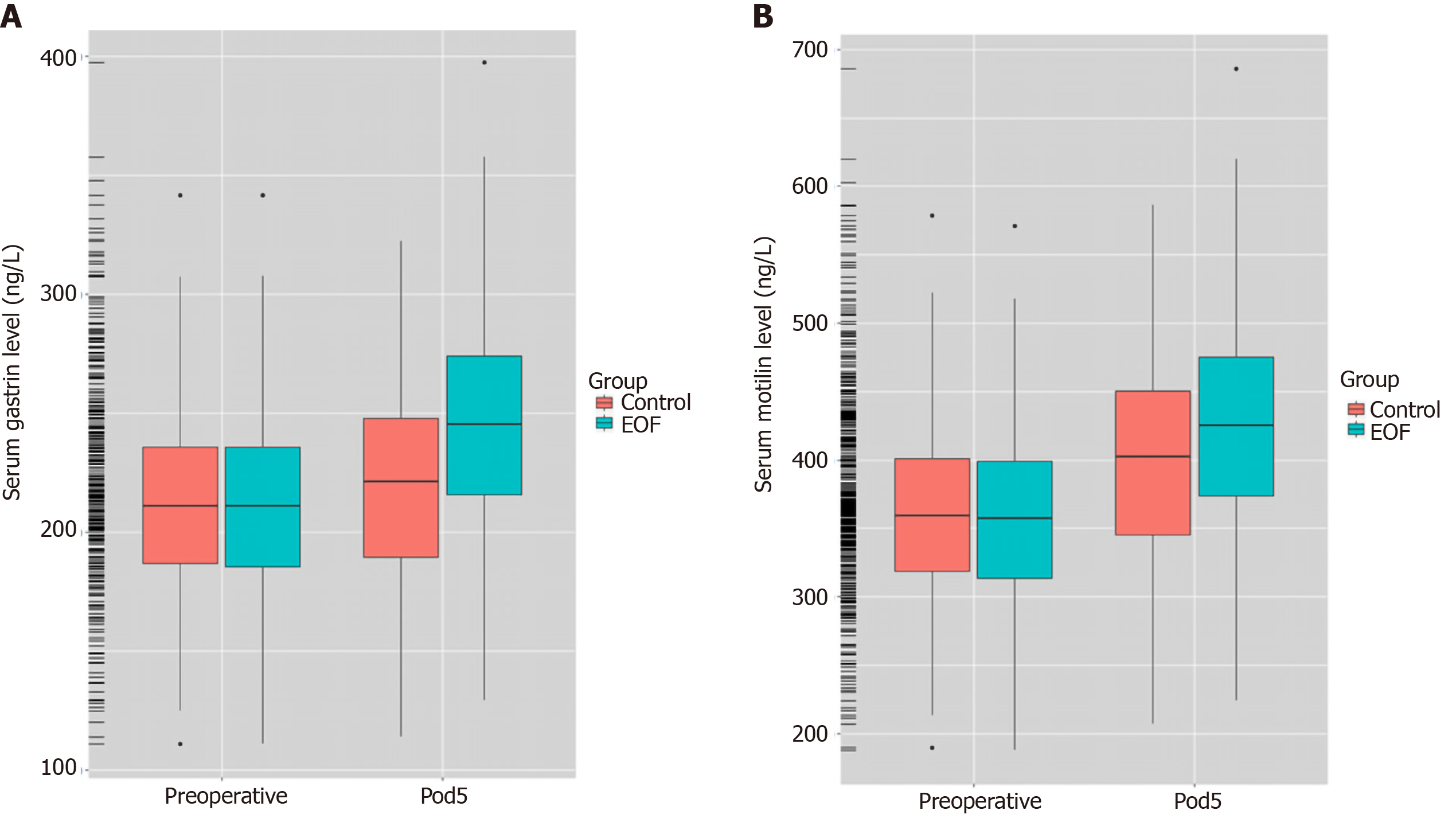

The serum levels of gastrin in the EOF group and the control group were (246.30 ± 57.10 ng/L vs 223.60 ± 55.70 ng/L, P = 0.001) on the 5th day after surgery; the serum levels of motilin in the EOF group and the control group were (424.60 ± 68.30 ng/L vs 409.30 ± 61.70 ng/L, P = 0.002) (Table 3, Figure 2).

The comparison between the two groups showed that the rate of abdominal distension, postoperative nausea and reinsertion of the nasogastric tube in the EOF group was slightly higher than that in the control group (20.95% vs 17.82%), but the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.507) (Table 3).

In terms of postoperative complications, there were no significant differences in the incidence of anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic or duodenal stump fistula, wound infection, postoperative pneumonia and postoperative ileus between the EOF group and the control group (17.14% vs 14.85%, P = 0.609) (Table 4).

| Group | EOF group, n = 105 | Control group, n = 101 | t value | P value |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Anastomotic bleeding | 1 | 2 | ||

| Anastomotic or duodenal stump fistula | 3 | 1 | ||

| Wound infection | 4 | 5 | ||

| Postoperative pneumonia | 3 | 4 | ||

| Postoperative ileus | 2 | 1 | ||

| Others1 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Total, % | 18 (17.14) | 15 (14.85) | 0.422 | 0.609 |

According to the median exhaust time, patients in this study were divided into early or delayed exhaust groups. Then, binary logistic regression analysis was performed. Univariate logistic analysis showed that the body mass index, operation time, dietary strategy (EOF) and postoperative serum gastrin level were significant factors affecting the first postoperative exhaust time. However, multivariate analysis showed that only the dietary strategy (EOF) was an independent factor affecting the first postoperative exhaust time (P < 0.001) (Tables 5 and 6).

| Index | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age, yr, < 60 or ≥ 60 | 0.477 | 0.187-1.221 | 0.123 |

| Gender, male or female | 0.764 | 0.241-1.165 | 0.653 |

| BMI, kg/m2, < 24 or ≥ 24 | 0.236 | 0.116-0.489 | 0.006 |

| TNM stage, I or II or III | 0.784 | 0.513-1.148 | 0.242 |

| Differentiation, poor, moderate, well | 0.899 | 0.543-1.256 | 0.308 |

| Operation time, min, < 180 or ≥ 180 | 0.581 | 0.355-0.953 | 0.042 |

| Blood loss, mL, < mean or ≥ mean | 1.210 | 0.884-1.597 | 0.762 |

| Early oral feeding, yes or no | 3.862 | 1.840-9.624 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative serum gastrin, ng/L, < mean or ≥ mean | 0.253 | 0.151-0.357 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative serum motilin, ng/L, < mean or ≥ mean | 0.630 | 0.214-1.107 | 0.163 |

| Index | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| BMI, kg/m2, < 24 or ≥ 24 | 1.060 | 0.649-1.733 | 0.081 |

| Operation time, min, < 180 or ≥ 180 | 1.519 | 0.578-3.990 | 0.396 |

| Early oral feeding, yes or no | 2.689 | 1.289-3.783 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative serum gastrin, ng/L, < mean or ≥ mean | 0.476 | 0.195-1.162 | 0.103 |

The nutritional status of GC patients is closely related to postoperative rehabilitation. According to Fukuda et al[19], malnutrition was prevalent in GC patients due to bleeding, obstruction or neoplastic factors, which was a risk factor associated with the incidence of postoperative adverse events. Therefore, active nutritional support should be considered after radical gastrectomy.

So far, there have been studies showing that patients who underwent gastrectomy can be supported by early postoperative enteral nutrition[3-5]. Moreover, Shoar et al[20] showed that for patients with upper gastrointestinal malignant tumors, EOF after surgery can lead to faster recovery and shorter postoperative hospitalization. Lopes et al[21] also indicated that early oral diet was safe and viable for patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal surgery. The studies of Laffitte et al[4] and Sierzega et al[5] showed that patients after radical gastrectomy could tolerate EOF, while there was no definite correlation between EOF and postoperative complications. According to a systematic review, current evidence for EOF after gastrectomy is promising[22]. However, in China, high-quality evidence focusing on the safety, feasibility and short-term clinical outcomes of EOF after GC surgery, especially laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy, is still scarce. Therefore, we designed and carried out this prospective cohort study.

Our results showed that compared with the control group, the time of first postoperative exhaust and defecation in the EOF group was shorter (P = 0.001, P = 0.004, respectively), which was consistent with the results of Sierzega et al[5]. In addition, compared with the control group, the levels of gastrointestinal hormones in the EOF group were significantly higher on postoperative day 5, which was in accordance with Gao et al[23] results. From our point of view, no placement of nasogastric tube and EOF after surgery can reduce the psychological and gastro-intestinal stress response of patients, which is conducive to speeding up the recovery of gastrointestinal function.

Our study also found that although the rate of abdominal distension, nausea and reinsertion of the nasogastric tube in the EOF group was slightly higher than that in the control group, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.507), indicating that most of the patients could tolerate EOF after surgery. According to a study carried out by Jo et al[24], postoperative nausea, vomiting and transient ileus were associated with hypervagotonia and inflammatory response after abdominal surgery, and EOF could relieve these symptoms.

PALB, also known as transthyretin, has a plasma half-life of approximately 1.9 d[25]. Compared with ALB, the serum PALB level can reflect the protein synthesis function more sensitively, which is a preferable and reliable index to evaluate the changes of nutritional status[26,27]. In this study, the levels of serum PALB in the EOF group were higher than those in the control group before discharge (P = 0.018). However, no significant differences were observed in terms of serum ALB. Li et al[28] compared the impact of early enteral nutrition combined with parenteral nutrition and total parenteral nutrition on patients after GC surgery, and a significant decrease was observed in PALB in the total parenteral nutrition group compared with the early enteral nutrition group (P < 0.01), which was in line with our results.

Beyond the above issues, most surgeons are more concerned about the safety of EOF after radical total gastrectomy. The safety can be evaluated by the incidence of postoperative mortality or complications, especially serious complications[29]. Our results showed that EOF after radical total gastrectomy did not increase the incidence of postoperative complications. There was no significant difference in the incidence of anastomotic fistula and duodenal stump fistula between the two groups. The differences between the two groups were not significant in terms of anastomotic bleeding, wound infection, postoperative pneumonia, postoperative intestinal obstruction, etc. According to the traditional feeding viewpoint, postoperative fasting and placement of the nasogastric tube can bring down the pressure in the digestive tract, reduce the anastomotic edema and provide sufficient time for anastomotic site healing. However, that does not seem to be the case. Rossetti et al[30] conducted a study on 145 patients after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and found that placement of the nasogastric tube was not helpful in reducing postoperative fistula incidence. In addition, a RCT study[31] demonstrated that routine placement of a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube after partial distal gastrectomy was not necessary in GC in terms of postoperative ileus prevention.

Our viewpoint is that the primary causes responsible for postoperative anastomotic fistula are diabetes, excessive anastomotic tension, anastomotic ischemia or defect of anastomotic technique, etc. Our experience is that fine operation plus exact and reliable anastomosis are the basis for prevention of anastomotic fistula. In addition, since the first case of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy[32] and the first case of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for advanced GC[33] were performed, laparoscopic radical gastrectomy has been rapidly popularized in recent years. Undoubtedly, the minimally invasive surgery, represented by laparoscopic surgery, has opened a new era of GC surgery and has obvious advantages in delicate operation[34].

In brief, our study, with the strengths such as a prospective design, moderate sample size and detailed laboratory examinations, further confirmed that EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy was safe and feasible. Yet, some limitations are in this study. First, it was a single center prospective cohort study, and multicenter prospective randomized controlled trials are expected to further validate our results. Furthermore, the sample size is still limited. Finally, the serum protein and gastrointestinal hormone changes were not monitored dynamically.

In conclusion, EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy promotes recovery of intestinal function, improves postoperative nutritional status, reduces the length of postoperative hospital stay and hospitalization costs and does not increase the incidence of related complications, which indicates its safety, feasibility and short-term potential benefits for GC patients.

Gastric cancer (GC) is a heavy burden in China. Nutritional support of GC patients is closely related to postoperative rehabilitation. However, the role of early oral feeding (EOF) after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy in GC patients is still unclear.

To prospectively explore the safety, feasibility and short-term clinical outcomes of EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy for GC patients.

The aim of this study was to study the role of EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy.

A prospective cohort study was conducted between January 2018 and December 2019 based in a high-volume tertiary hospital in China. Two hundred and six patients who underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy for GC were enrolled. Of which, 105 patients were given EOF (EOF group) after surgery, and the other 101 patients were given traditional feeding strategy (control group) after surgery. Perioperative data were collected. The primary endpoints were gastrointestinal function recovery time and postoperative complications, and the secondary endpoints were postoperative nutritional status, length of hospital stay and expenses, etc.

Compared with the control group, patients in the EOF group had a significantly shorter postoperative first exhaust time (2.48 ± 1.17 d vs 3.37 ± 1.42 d, P = 0.001) and first defecation time (3.83 ± 2.41 d vs 5.32 ± 2.70 d, P = 0. 004). The EOF group had a significantly shorter postoperative hospitalization duration (5.85 ± 1.53 d vs 7.71 ± 1.56 d, P < 0.001) and fewer postoperative hospitalization expenses (16.60 ± 5.10 K¥ vs 21.00 ± 7.50 K¥, P = 0.014). On the 5th day after surgery, serum prealbumin level (214.52 ± 22.47 mg/L vs 204.17 ± 20.62 mg/L, P = 0.018), serum gastrin level (246.30 ± 57.10 ng/L vs 223.60 ± 55.70 ng/L, P = 0.001) and serum motilin level (424.60 ± 68.30 ng/L vs 409.30 ± 61.70 ng/L, P = 0.002) were higher in the EOF group. However, there was no significant difference in incidence of total postoperative complications between the two groups (P = 0.609).

EOF after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy can promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function, improve postoperative nutritional status, reduce length of hospital stay and expenses while not increasing the incidence of related complications, which indicates the safety, feasibility and potential benefits of EOF for GC patients.

In this study, we proved the safety, feasibility and potential benefits of EOF for GC patients after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy. Considering the limitations of this study, multicenter prospective randomized controlled trials with a large sample size are expected to further validate the conclusions of this study.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56651] [Article Influence: 7081.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (134)] |

| 2. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13323] [Article Influence: 1332.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Hur H, Kim SG, Shim JH, Song KY, Kim W, Park CH, Jeon HM. Effect of early oral feeding after gastric cancer surgery: a result of randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 2011;149:561-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Laffitte AM, Polakowski CB, Kato M. Early oral re-feeding on oncology patients submitted to gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sierzega M, Choruz R, Pietruszka S, Kulig P, Kolodziejczyk P, Kulig J. Feasibility and outcomes of early oral feeding after total gastrectomy for cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Hütterer E, Isenring E, Kaasa S, Krznaric Z, Laird B, Larsson M, Laviano A, Mühlebach S, Muscaritoli M, Oldervoll L, Ravasco P, Solheim T, Strasser F, de van der Schueren M, Preiser JC. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:11-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1318] [Cited by in RCA: 1941] [Article Influence: 194.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG, Soop M, de Boer HD, Urman RD, Chang GJ, Fichera A, Kessler H, Grass F, Whang EE, Fawcett WJ, Carli F, Lobo DN, Rollins KE, Balfour A, Baldini G, Riedel B, Ljungqvist O. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019;43:659-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1071] [Cited by in RCA: 1378] [Article Influence: 196.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamagata Y, Yoshikawa T, Yura M, Otsuki S, Morita S, Katai H, Nishida T. Current status of the "enhanced recovery after surgery" program in gastric cancer surgery. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Che G. [Establishment and Optimization of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery System for Lung Cancer]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2017;20:795-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CH, Garden OJ, Farges O, Kokudo N, Vauthey JN, Clavien PA, Demartines N. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40:2425-2440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, Glaser G, Altman A, Meyer LA, Taylor JS, Iniesta M, Lasala J, Mena G, Scott M, Gillis C, Elias K, Wijk L, Huang J, Nygren J, Ljungqvist O, Ramirez PT, Dowdy SC. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:651-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 69.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shimizu N, Oki E, Tanizawa Y, Suzuki Y, Aikou S, Kunisaki C, Tsuchiya T, Fukushima R, Doki Y, Natsugoe S, Nishida Y, Morita M, Hirabayashi N, Hatao F, Takahashi I, Choda Y, Iwasaki Y, Seto Y. Effect of early oral feeding on length of hospital stay following gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a Japanese multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Surg Today. 2018;48:865-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hong L, Han Y, Zhang H, Zhao Q, Liu J, Yang J, Li M, Wu K, Fan D. Effect of early oral feeding on short-term outcome of patients receiving laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:637-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen J, Xu M, Zhang Y, Gao C, Sun P. Effects of a stepwise, local patient-specific early oral feeding schedule after gastric cancer surgery: a single-center retrospective study from China. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang J, Yang M, Wang Q, Ji G. Comparison of Early Oral Feeding With Traditional Oral Feeding After Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1953] [Article Influence: 217.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study Group(CLASS), Gastric Cancer Professional Committee of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery Group. Chinese Medical Association Surgical Branch. [Standard operation procedure of laparoscopic D2 distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: consensus on CLASS-01 trial]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;22:807-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hübner M, Klek S, Laviano A, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN, Martindale R, Waitzberg DL, Bischoff SC, Singer P. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:623-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 859] [Cited by in RCA: 1134] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Nishikawa K, Maeda S, Haraguchi N, Miyake M, Hama N, Miyamoto A, Ikeda M, Nakamori S, Sekimoto M, Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T. Prevalence of Malnutrition Among Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Gastrectomy and Optimal Preoperative Nutritional Support for Preventing Surgical Site Infections. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S778-S785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shoar S, Naderan M, Mahmoodzadeh H, Hosseini-Araghi N, Mahboobi N, Sirati F, Khorgami Z. Early Oral Feeding After Surgery for Upper Gastrointestinal Malignancies: A Prospective Cohort Study. Oman Med J. 2016;31:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lopes LP, Menezes TM, Toledo DO, DE-Oliveira ATT, Longatto-Filho A, Nascimento JEA. Early oral feeding post-upper gastrointestinal tract resection and primary anastomosis in oncology. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2018;31:e1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tweed T, van Eijden Y, Tegels J, Brenkman H, Ruurda J, van Hillegersberg R, Sosef M, Stoot J. Safety and efficacy of early oral feeding for enhanced recovery following gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A systematic review. Surg Oncol. 2019;28:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gao L, Zhao Z, Zhang L, Shao G. Effect of early oral feeding on gastrointestinal function recovery in postoperative gastric cancer patients: a prospective study. J BUON. 2019;24:194-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jo DH, Jeong O, Sun JW, Jeong MR, Ryu SY, Park YK. Feasibility study of early oral intake after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ando Y. [Transthyretin-its function and pathogenesis]. Rinsho Byori. 2006;54:497-502. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Keller U. Nutritional Laboratory Markers in Malnutrition. J Clin Med. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 68.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhou J, Hiki N, Mine S, Kumagai K, Ida S, Jiang X, Nunobe S, Ohashi M, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Role of Prealbumin as a Powerful and Simple Index for Predicting Postoperative Complications After Gastric Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:510-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li B, Liu HY, Guo SH, Sun P, Gong FM, Jia BQ. Impact of early enteral and parenteral nutrition on prealbumin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein after gastric surgery. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:7130-7135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim W, Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Kim CY, Yang HK, Park DJ, Song KY, Lee SI, Ryu SY, Lee JH, Lee HJ; Korean Laparo-endoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group. Decreased Morbidity of Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy Compared With Open Distal Gastrectomy for Stage I Gastric Cancer: Short-term Outcomes From a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (KLASS-01). Ann Surg. 2016;263:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Rossetti G, Fei L, Docimo L, Del Genio G, Micanti F, Belfiore A, Brusciano L, Moccia F, Cimmino M, Marra T. Is nasogastric decompression useful in prevention of leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? A randomized trial. J Invest Surg. 2014;27:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pacelli F, Rosa F, Marrelli D, Morgagni P, Framarini M, Cristadoro L, Pedrazzani C, Casadei R, Cozzaglio L, Covino M, Donini A, Roviello F, de Manzoni G, Doglietto GB. Naso-gastric or naso-jejunal decompression after partial distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Final results of a multicenter prospective randomized trial. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:725-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kitano S, Tomikawa M, Iso Y, Hashizume M, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted devascularization of the lower esophagus and upper stomach in the management of gastric varices. Endoscopy. 1994;26:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Goh PM, Khan AZ, So JB, Lomanto D, Cheah WK, Muthiah R, Gandhi A. Early experience with laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Quan Y, Huang A, Ye M, Xu M, Zhuang B, Zhang P, Yu B, Min Z. Comparison of laparoscopic vs open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: an updated meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:939-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lieto E, Ueno M S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ