Published online Jun 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i24.3447

Peer-review started: February 1, 2020

First decision: March 6, 2020

Revised: March 29, 2020

Accepted: June 12, 2020

Article in press: June 12, 2020

Published online: June 28, 2020

Processing time: 148 Days and 0.5 Hours

Gastric cancer is the world’s third most lethal malignancy. Most gastric cancers develop through precancerous states of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Two staging systems, operative link for gastritis assessment (OLGA) and operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment (OLGIM), have been developed to detect high gastric cancer risk. European guidelines recommend surveillance for high-risk OLGA/OLGIM patients (stages III–IV), and for those with advanced stage of atrophic gastritis in the whole stomach mucosa. We hypothesize, that by combining atrophy and intestinal metaplasia into one staging named TAIM, more patients with increased gastric cancer risk could be detected.

To evaluate the clinical value of the OLGA, OLGIM, and novel TAIM stagings as prognostic indicators for gastric cancer.

In the Helsinki Gastritis Study, 22346 elderly male smokers from southwestern Finland were screened for serum pepsinogen I (PGI). Between the years 1989 and 1993, men with low PGI values (PGI < 25 μg/L), were invited to undergo an oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. In this retrospective cohort study, 1147 men that underwent gastroscopy were followed for gastric cancer for a median of 13.7 years, and a maximum of 27.3 years. We developed a new staging system, TAIM, by combining the topography with the severity of atrophy or intestinal metaplasia in gastric biopsies. In TAIM staging, the gastric cancer risk is classified as low or high.

Twenty-eight gastric cancers were diagnosed during the follow-up, and the incidence rate was 1.72 per 1000 patient-years. The cancer risk associated positively with TAIM [Hazard ratio (HR) 2.70, 95%CI: 1.09–6.69, P = 0.03]. The risk increased through OLGIM stages 0-IV (0 vs IV: HR 5.72, 95%CI: 1.03–31.77, P for trend = 0.004), but not through OLGA stages 0–IV (0 vs IV: HR 5.77, 95%CI: 0.67–49.77, P for trend = 0.10). The sensitivities of OLGA and OLGIM stages III–IV were low, 21% and 32%, respectively, whereas that of TAIM high-risk was good, 79%. On the contrary, OLGA and OLGIM had high specificity, 85% and 81%, respectively, but TAIM showed low specificity, 42%. In all three staging systems, the high-risk men had three- to four-times higher gastric cancer risk compared to the general male population of the same age.

OLGIM and TAIM stagings show prognostic value in assessing gastric cancer risk in elderly male smokers with atrophic gastritis.

Core tip: In low-risk countries, most gastric cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage without possibility for curative treatment. There is a need for better selection of patients with precancerous findings for surveillance. Operative link for gastritis assessment (OLGA) and operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment (OLGIM) staging systems provide a useful tool to evaluate the gastric cancer risk. We have developed a novel staging, TAIM, which combines atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Our results support the earlier findings that OLGIM detects high-risk patients better than OLGA, and with TAIM staging, even more patients could be detected and forwarded for beneficial endoscopic surveillance.

- Citation: Nieminen AA, Kontto J, Puolakkainen P, Virtamo J, Kokkola A. Comparison of operative link for gastritis assessment, operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment, and TAIM stagings among men with atrophic gastritis. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(24): 3447-3457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i24/3447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i24.3447

The incidence of gastric cancer across the globe varies considerably. Half of new gastric cancer cases occur in eastern Asia, with highest incidence rates in China, Japan, and South Korea. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased continuously during the past half century, worldwide it remains the fifth most common malignancy, and the third leading cause of cancer related death[1]. The gastric cancer incidence is low in western countries. In 2018, the Finnish age-standardized incidence for men was 5.5/100000 and for women was 3.6/100000[2]. In the West, the majority of gastric cancers are diagnosed at advanced stages, and the overall five-year survival rate is only about 25%[2]. Cancer cases cumulate to older age groups, and male predominance is seen in all parts of the world[1].

Gastric carcinomas can be divided into intestinal and diffuse types by histology, or they may have features of both histological types (mixed type)[3]. The development of gastric cancer takes several years, and multiple precancerous alterations in gastric mucosa may precede intestinal types of gastric cancer[4]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection triggers inflammation in gastric mucosa, and when persistent, can be followed by atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia, and finally gastric adenocarcinoma, a pathway called Correa’s cascade[5].

Pepsinogen I (PGI) is produced by oxyntic mucosa of the stomach, and PGII by both oxyntic and antral mucosa. Serum pepsinogen tests have been used as an indirect, noninvasive method for gastric cancer screening[6]. Now radiographic and endoscopic screenings are recommended for high-risk populations[7]. Population screening programs for gastric cancer are organized in high-risk countries, such as in Japan and South Korea[8], thus, cancers can be detected earlier allowing more commonly curative treatment.

Gastric biopsy samples are evaluated by using updated Sydney System, in which the intensity of inflammatory cells, H. pylori density, atrophy, and IM are graded to normal, mild, moderate, or marked[9]. Based on histological grading using the Sydney System, two staging systems have been created to detect patients with increased gastric cancer risk. The operative link for gastritis assessment (OLGA)[10] and operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment (OLGIM)[11] score histological findings of gastric biopsies. In OLGA staging, the degree of atrophy is determined by Sydney system’s[9] four-tiered scale (0–3), and severity of atrophy in antrum and corpus are cross tabulated and staged. Cancer risk increases with stages from 0 to IV, stages III–IV representing high cancer risk. In OLGIM staging atrophy is replaced by IM[12-16]. Inter-observer agreement between pathologists is better in OLGIM staging[17], but OLGA staging is proposed to be more sensitive in finding patients with high risk of gastric cancer[18].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical value of a novel staging system, TAIM, which combines the topography with the severity of atrophy and IM. By using both atrophy and IM grading as a basis, we think there is a greater probability to find patients with increased cancer risk. We also wanted to compare TAIM with the OLGA and OLGIM staging systems in elderly men with atrophic gastritis.

Altogether 29133 elderly male smokers, participated in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to examine effects of supplemental alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene, or both on the incidence of lung and other cancers between years 1985-1993[19,20]. Serum PGI levels were measured from 22346 participants and low (< 25 μg/L) PGI levels, as a marker for atrophic corpus gastritis, were observed in 2132 men[21]. These men were invited to undergo upper GI endoscopy, which was performed on 1344 men between 1989 and 1993. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Men with diagnosed gastric cancer (n = 14) or neuroendocrine tumor (n = 3) in the screening endoscopy or within less than hundred days were excluded, as well as, 180 men with a history of gastric surgery due to a benign cause. Thus, 1147 men were included into the study.

The surveillance started from the screening gastroscopy, and continued to the diagnosis of gastric cancer, death, or the end of the year 2016, whichever occurred first. The median follow-up time was 13.7 years (range 16 d to 27.3 years) and comprised 16297 patient-years. For standardized incidence ratio (SIR) calculations, general male population of same age was used as a reference. The follow-up data was achieved from the Finnish Cancer Registry and the Population Register Centre of Finland. The Ethical Issues’ Committee of the National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, gave approval for the Helsinki Gastritis Study. All men gave a written agreement to take part in the ATBC Study and Helsinki Gastritis Study, including this follow-up study. The results of the follow-up have been introduced previously[22].

In OLGA and OLGIM stagings atrophy and IM are determined separately. We sought to combine these two precancerous mucosal changes to one staging system. TAIM is based on the severity and topography of atrophy and IM. The most severe finding of atrophy or IM defines the degree of severity (non-existing, mild, moderate, marked) regardless of its topography. Then, its location is designated to the antrum only, corpus only, or both antrum and corpus. The distribution of severity is examined in the different locations and the TAIM subgroups are classified as low and high. In addition to TAIM staging, OLGA and OLGIM stages are presented in Table 2.

| Severity | Location | ||

| Antrum | Corpus | Whole stomach | |

| No atrophy/IM | Low (0) | Low (0) | Low (0) |

| Mild atrophy/IM | Low (I) | Low (I) | Low (I) |

| Moderate atrophy/IM | Low (II) | Low (II) | High (II-III) |

| Marked atrophy/IM | High (III) | High (II) | High (IV) |

European guidelines (MAPSII)[23] recommend endoscopic surveillance for patients with extensive (moderate to marked) atrophy or IM in both antrum and corpus, and OLGA/OLGIM stages III–IV. Patients with low or moderate changes in a single location do not require endoscopic surveillance. Type of IM (complete/incompelete), family history of gastric cancer, autoimmune gastritis, and persisting H. Pylori infection are also taken into account in follow-up recommendations, and if there are additional risk factors, surveillance is recommended even if moderate to marked IM exists in a single location only. Therefore, patients with severe atrophy/IM in corpus only, representing OLGA and OLGIM II stages, are classified to high cancer risk group in TAIM staging. Ten men in the OLGA and TAIM groups and seven men in the OLGIM group had incomplete histological analysis. None of these men developed gastric cancer.

Statistical analysis was performed by R program[24]. Cox regression models were used to analyse the association between the staging systems and the risk of gastric cancer. Age, number of cigarettes smoked daily, and smoking-years were regarded as confounding variables. Several dietary components, as well as supplementation of alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene, or combination of these two supplements, had no influence on the risk of gastric cancers, and were therefore disregarded. Trend across the hazard ratios was tested using Wald test. Cumulative event rate curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and log-rank test was used to evaluate the differences between the curves. P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

Twenty-eight gastric cancers (2.4%) were diagnosed during the follow-up. The total incidence rate per 1000 patient-years was 1.72.

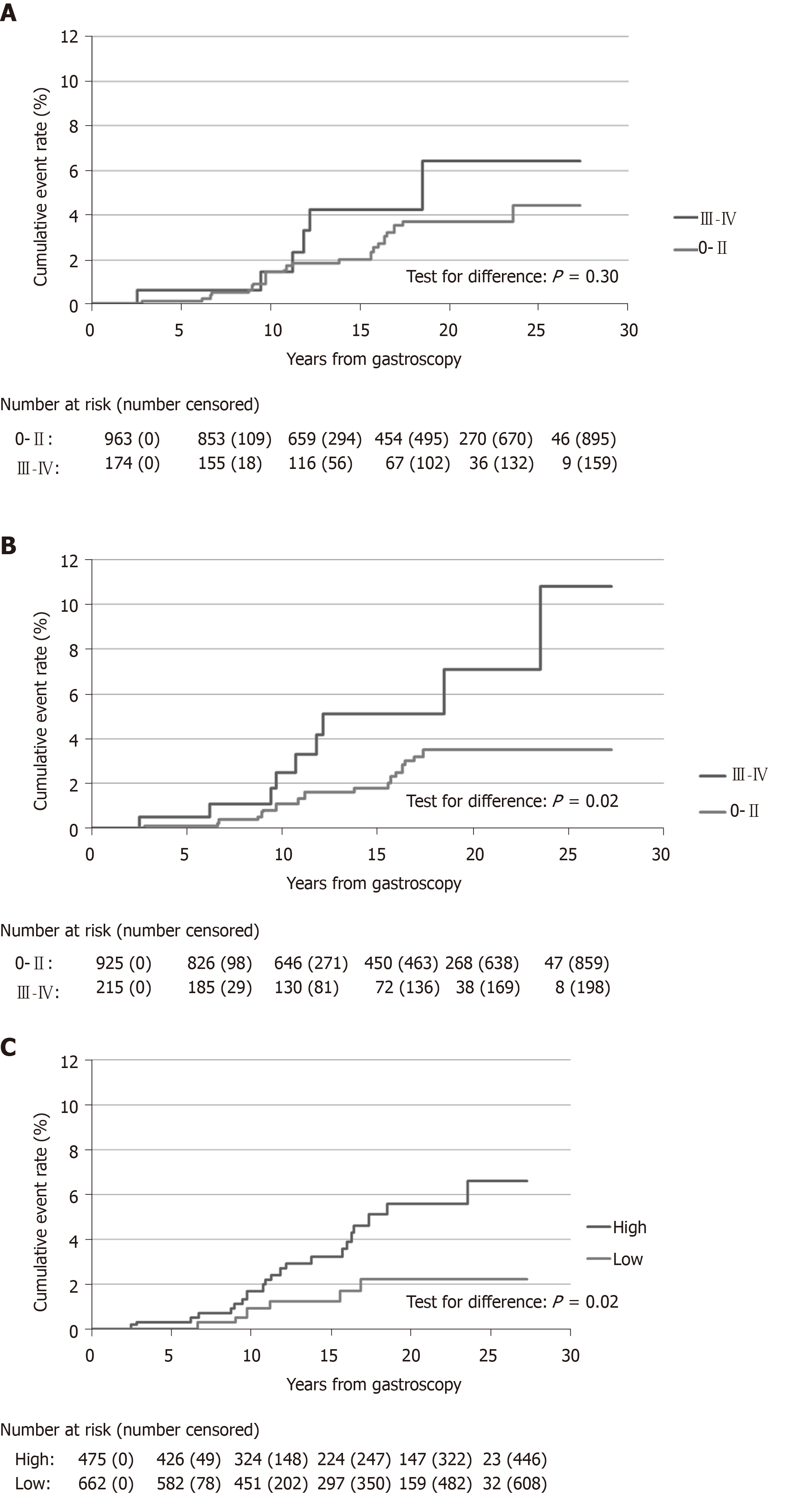

The OLGA staging and number of men gastroscopied and incident gastric cancer cases in each subgroup are shown in Table 3. The incidence rates of gastric cancer were 0.62, 1.60, 1.75, 1.11, and 3.40 per 1000 patient-years in stages 0–IV, respectively, (P for trend 0.10, Table 4). The majority of gastric cancers (n = 22, 79%) were diagnosed in low-risk OLGA stages (0–II), and only six cancers (21%) in high-risk (III–IV) stages. At the end of follow-up the cumulative cancer event rate was 4.4% in OLGA stages 0–II, and 6.4% in stages III–IV (Figure 1A).

| Corpus | ||||

| 0 (No atrophy) | 1 (Mild) | 2 (Moderate) | 3 (Marked) | |

| Antrum 0 (No atrophy) | 0 (1/103) | I (3/116) | II (7/395) | II (8/259) |

| Antrum 1 (Mild) | I (0/5) | I (0/15) | II (3/60) | III (0/26) |

| Antrum 2 (Moderate) | II (0/4) | II (0/6) | III (1/32) | IV (1/26) |

| Antrum 3 (Marked) | III (0/0) | III (0/7) | IV (2/41) | IV (2/42) |

| n | Gastric cancers | H. pylori pos (%) | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| OLGA stage | ||||||

| 0 | 103 | 1 | 25.2 | 1.00 | ||

| I | 136 | 3 | 44.1 | 2.66 | 0.28-25.72 | |

| II | 724 | 18 | 24.7 | 2.84 | 0.38-21.38 | 0.10 |

| III | 65 | 1 | 35.4 | 1.85 | 0.11-29.87 | |

| IV | 109 | 5 | 25.7 | 5.77 | 0.67-49.77 | |

| OLGIM stage | ||||||

| 0 | 205 | 2 | 33.7 | 1.00 | ||

| I | 404 | 7 | 28.0 | 1.82 | 0.37-8.83 | |

| II | 316 | 10 | 27.8 | 3.55 | 0.77-16.36 | 0.004 |

| III | 115 | 5 | 26.1 | 5.91 | 1.14-30.73 | |

| IV | 100 | 4 | 18.0 | 5.72 | 1.03-31.77 | |

| TAIM stage | ||||||

| Low | 475 | 6 | 32.6 | 1.00 | ||

| High | 662 | 22 | 24.3 | 2.70 | 1.09-6.69 | 0.03 |

The OLGIM staging and number of men gastroscopied and incident gastric cancer cases in each subgroup are shown in Table 5. The gastric cancer incidence rate increased by OLGIM stages being 0.62, 1.21, 2.24, 3.37, and 3.22 per 1000 patient-years in stages 0–IV, respectively, (P for trend 0.004, Table 4). Similar to OLGA stages, the majority of cancers appeared in low-risk OLGIM groups (0–II, n = 19, 68%), and the minority in high-risk groups (III–IV, n = 9, 32%). In the end of the follow-up in OLGIM stages 0–II, the cumulative gastric cancer event rate was 3.5%, and in stages III–IV, 10.8% (Figure 1B). Three men with OLGA or OLGIM stage 0 developed gastric cancer, of which one lacked atrophy, and two lacked IM in antrum and corpus biopsies.

| Corpus | ||||

| 0 (No IM) | 1 (Mild) | 2 (Moderate) | 3 (Marked) | |

| Antrum 0 (No IM) | 0 (2/205) | I (2/239) | II (5/133) | II (2/31) |

| Antrum 1 (Mild) | I (2/45) | I (3/120) | II (1/88) | III (1/39) |

| Antrum 2 (Moderate) | II (0/15) | II (2/49) | III (2/45) | IV (1/32) |

| Antrum 3 (Marked) | III (1/14) | III (1/17) | IV (2/30) | IV (1/38) |

The TAIM staging and number of men undergoing gastroscopy, and incident gastric cancer cases in each subgroup are shown in Table 6. In the TAIM scoring system the risk of gastric cancer was graded into two categories: low and high (Table 2). The cancer incidence rates in these groups were 0.87 and 2.37 per 1000 patient years, respectively (P for trend 0.03, Table 4). The cumulative gastric cancer event rates at the end of follow-up were 2.2% for low and 6.6% for high cancer risk stages (Figure 1C). One patient with healthy mucosa developed gastric cancer during the follow-up period. Most (26/28) of the gastric cancers were diagnosed in men with moderate or marked IM or atrophic corpus gastritis, or pangastritis. The high-risk group of TAIM staging detected 79% (22/28) of gastric cancer cases. Gastric cancer risk for the first ten years of surveillance was small and similar in low and high-risk groups, but increased thereafter in high-risk OLGIM (stages III-IV) patients and marginally in high-risk TAIM patients (Figure 1).

| Severity | Location | ||

| Antrum | Corpus | Whole stomach | |

| No atrophy/IM | 0 | 0 | 1/74 |

| Mild atrophy /IM | 0/14 | 1/87 | 0/35 |

| Moderate atrophy /IM | 0/5 | 4/260 | 8/235 |

| Marked atrophy /IM | 0 | 5/179 | 9/248 |

Histology of H. pylori was analyzed from biopsies taken in the primary gastroscopies, and the results are shown in Table 4. Serological data of H. pylori was not available.

The sensitivity and specificity of the different staging systems to predict gastric cancer are shown in Table 7. The high-risk groups of OLGA and OLGIM stagings (III–IV) were not as sensitive, 21.4% and 32.1%, respectively, as the high-risk group of TAIM staging, 78.6%, to predict gastric cancer risk. On the other hand, specificity of OLGA and OLGIM stagings were 84.9% and 81.4%, respectively, whereas TAIM staging had weak specificity - 42.3% (Table 7).

| Cases/Men | % | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

| OLGA | ||||

| 0-II | 22/963 | 2.28 | 21.4 | 84.9 |

| III-IV | 6/174 | 3.45 | ||

| OLGIM | ||||

| 0-II | 19/925 | 2.05 | 32.1 | 81.4 |

| III-IV | 9/215 | 4.19 | ||

| TAIM | ||||

| low | 6/475 | 1.26 | 78.6 | 42.3 |

| high | 22/662 | 3.32 | ||

Total 259 men (23%) had marked atrophy in corpus biopsies, but not in antral samples. Eight of these men developed gastric cancer during the follow-up. Some of the men might have had an autoimmune gastritis, but exact number is lacking because autoantibodies against parietal cells or intrinsic factor were not determined.

SIRs were calculated, and compared to the general, male population of the same age (SIR 1.0) (Table 8). In OLGA and OLGIM stagings SIRs were elevated in both low- and high-risk patients, and in TAIM staging in high-risk patients compared to the general male population. In all staging systems, high-risk patients had three- to four-times higher cancer risk compared to the general population.

| SIR | 95%CI | P value | |

| OLGA | |||

| General population | 1.00 | ||

| Low (0-II) | 2.10 | 1.32-3.18 | 0.003 |

| High (III-IV) | 3.03 | 1.11-6.60 | 0.03 |

| OLGIM | |||

| General population | 1.00 | ||

| Low (0-II) | 1.86 | 1.12-2.90 | 0.02 |

| High (III-IV) | 4.00 | 1.83-7.60 | 0.001 |

| TAIM | |||

| General population | 1.00 | ||

| Low-risk | 1.17 | 0.43-2.54 | 0.82 |

| High-risk | 3.00 | 1.88-4.55 | < 0.001 |

The risk for gastric cancer is low in western countries, and with a lack of screening programs, the majority of gastric cancers are detected at an advanced stage. There is a need to detect and follow patients at highest risk of developing gastric cancer. The present study has, to our knowledge, the longest follow-up of OLGA- and OLGIM-staged participants, with maximum follow-up of 27.3 years, and at the same time also the largest number of gastric cancers diagnosed in OLGA/OLGIM-scored patients. We developed a new staging system, TAIM, which divides patients into low- and high-risk groups of developing gastric cancer, depending on the degree of the atrophy or IM and their topography in stomach.

In our materials, OLGA staging was not significantly associated with the risk of gastric cancer. This was unsurprising as all men had low serum PGI levels at the beginning of the study, and thereby corpus atrophy was expected. Conversely, an elevated OLGIM stage was associated with increased gastric cancer risk. Men with IM in their stomach may have a more advanced premalignant stage for the development of clinical gastric cancer. In a nationwide cohort study from the Netherlands, the risk for gastric cancer after 10 years of follow-up was 0.8% in patients with atrophic gastritis and 1.8% with IM[25]. In a Swedish study by Song et al[26], gastric cancer risk was 2.8 times higher in people with atrophic gastritis, and 3.2 times higher with IM compared to people with normal biopsies.

European guidelines (MAPSII) recommend endoscopical surveillance every three years for patients with extensive gastric atrophy and/or IM in whole stomach[23]. Although the men in this study had risk factors and precancerous findings, only 2.4% of them developed gastric cancer during the follow-up period, with an annual gastric cancer incidence rate of 0.17%.

Most patients and the majority of gastric cancers accumulated to so-called low-risk OLGA and OLGIM stages (0–II). These staging systems would have missed most gastric cancers which render these systems less useful compared to the new TAIM staging system. The majority of patients (n = 662/1147) and diagnosed gastric cancers (n = 22/28) assembled to the TAIM high cancer risk group, and TAIM staging was associated with the risk of gastric cancer. High-risk OLGA and OLGIM stages in primary endoscopy predicted only 21% (6/28) and 32% (9/28) of the cancer cases (OLGA and OLGIM, respectively). The new staging, in contrast, revealed 79% (22/28) of incident gastric cancers. Compared to the general male population of the same age, SIRs were elevated in OLGA and OLGIM stagings in both low and high-risk patients. In TAIM staging the difference between low and high-risk groups differed (TAIM low-risk SIR 1.17, P = 0.82, and TAIM high-risk SIR 3.00, P < 0.001, respectively), and therefore TAIM could be best of these three stagings to segregate patients, who should be followed up. However, the specificity of TAIM staging was lower than in OLGA and OLGIM stagings. The low specificity of TAIM high-risk means more men require gastric cancer follow-up. In addition, the number of gastroscopies depends on the frequency of follow-ups. Two men in the high-risk group of TAIM were diagnosed with clinical gastric cancer within three years of undergoing a screening gastroscopy. The optimal frequency of follow-up gastroscopies to prevent as many clinical gastric cancers as possible must be examined in further studies, however.

In OLGA and OLGIM stagings, marked atrophy or IM in biopsy samples from antrum or incisura angularis without preneoplastic changes in corpus, represent OLGA/OLGIM stage III, and if changes are reversed in corpus and antrum, the stage is II. In autoimmune gastritis atrophy is restricted to corpus only, and IM can be non-existing or minimal. These patients represent OLGA stage II. By OLGIM staging, patients with autoimmune gastritis, cannot be evaluated. TAIM staging emphasizes changes in corpus and whole stomach, as these represent long lasted gastritis of H. Pylori induced corpus predominant gastritis, or autoimmune gastritis. It is notable, that patient material is biased. The participants were elderly male smokers, who were selected based on low serum PGI and no men with normal stomachs or superficial gastritis were present. The number of men with atrophy or IM only in antrum biopsies was low, which biases the topographic distribution, and therefore TAIM score. This is the first time to test this staging and thereby results are preliminary and validation studies are needed.

Average 30% of men had positive H. pylori histology. These findings are based on biopsies from screening gastroscopies. Because of lacking serology, the number of H. pylori positive patients might be larger.

In the screening gastroscopy, the OLGA/OLGIM stage 0 and TAIM low-risk groups failed to predict a non-existing risk of gastric cancer. Three men with OLGA/OLGIM stage 0, and one in the low-risk TAIM group developed gastric cancer. One possible explanation for this is sampling error, as these men had low serum PGI values, and some degree of atrophy would have been expected. Multifocal atrophic gastritis appears in a spotted manner, and these samples might be taken from healthy areas. A small proportion of gastric cancers also appear in patients with normal gastric mucosa. In addition, due to laboratory measurement error, some low serum pepsinogen values may have been false positive. Another explanation is a long follow-up time. Precancerous changes of these men might have been invisible or non-existing at the time of endoscopy and cancer developed during the next few decades. One patient with stage 0 OLGIM had diffuse gastric cancer, but otherwise histological data is missing for these patients. H. pylori induced superficial gastritis can also lead to diffuse type of gastric cancer and can explain why one patient with OLGIM stage 0 developed gastric cancer. Typically marked atrophy and IM precede intestinal type of gastric cancer, whereas a diffuse type cancer may arise from superficial gastritis or from normal mucosa. Normal serum PGI level or nonatrophic mucosa in gastric biopsies does not indicate that the risk of gastric cancer is zero. Patients with a diffuse type of gastric cancer represent generally low OLGA and OLGIM stages[11,18]. The sensitivity of pepsinogen testing is poor in a diffuse type of gastric cancer[27], but should not have had an influence on our results, as all men had low PGI. The histological reports of cancers were not sufficiently available, but histological type could explain why some cancers developed in patients with low OLGA / OLGIM/TAIM stages.

In conclusion, OLGIM and TAIM staging systems showed prognostic value in male smokers with atrophic gastritis. However, most gastric cancers were diagnosed in low OLGA and OLGIM stages (0–II). TAIM staging could hold more potential to find patients with increased cancer risk, but these results are preliminary and further validation studies are needed.

Majority of gastric cancers (GC) of intestinal type develop through precancerous states of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (IM). Precancerous changes, male gender, smoking, and aging are risk factors for GC. Two staging systems have previously been developed to predict GC risk. Operative link for gastritis assessment (OLGA) staging assesses the degree of atrophy in gastric biopsies, and in operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment (OLGIM) staging, atrophy is replaced with IM.

In low-risk gastric cancer countries there are no screening programs, and five-year survival of GC patients is poor. There is a need to specify patients at highest risk. In this study, the usability of OLGA and OLGIM stagings were evaluated. In addition, we developed a new staging system named TAIM (abbreviation from topography, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia), which combines atrophy and IM into one staging.

The main objectives were to evaluate OLGA, OLGIM, and TAIM stagings in predicting long-term GC risk in elderly male smokers with low pepsinogen I (PGI). The main questions were: Can OLGA and OLGIM stagings segregate patients with highest GC risk among those with several risk factors? What is the predictive value of TAIM staging when compared to OLGA and OLGIM?

In this retrospective cohort study, 1147 elderly smoking men with low PGI, as a marker of atrophic corpus gastritis, participated in screening gastroscopies. The median follow-up was 13.7 years, and maximum over 27 years. Gastroscopy biopsy specimen were analyzed by using Updated Sydney System, and then scored by OLGA, OLGIM, and TAIM staging systems. In TAIM staging, the most severe finding of atrophy or IM defined the degree of severity (non-existing, mild, moderate, or marked), and then changes were evaluated to exist in antrum only, corpus only, or in whole stomach. The GC risk was scored as low or high in TAIM staging. The GC risk was compared to age and gender matched general population in all three staging systems. The follow-up data was achieved from the Finnish Cancer Registry and the Population Register Centre of Finland.

Twenty-eight gastric cancers were diagnosed during the follow-up period. For the first ten years there was no notable difference in GC risk between low and high-risk patients, but thereafter the difference started to separate. OLGIM and TAIM stagings showed statistically significant difference in GC risk when risk scores increased. In all high-risk groups, the GC risk was three to four times higher compared to general male population of same age.

OLGIM and TAIM showed predictive value in evaluating the gastric cancer risk among elderly male smokers. Combining atrophy and IM into one staging system can be promising. Our results are preliminary, and TAIM staging has not been tested previously. Unlike patients in low risk TAIM group, OLGA and OLGIM both low (0-II) and high (III-IV) cancer risk groups and TAIM high risk group showed statistically significantly increased gastric cancer risk compared to the general population, respectively.

In the future, TAIM staging should be evaluated in other populations in both genders and different age groups. The results would be interesting to see in low- and high-risk countries.

We want to thank Professor Pentti Sipponen for his valuable comments and histological analysis of biopsy specimens; and Adjunct Professor, PhD Satu Männistö and Project Coordinator Anne Söderqvist for their help with collecting and assessing the data.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018. |

| 2. | Finnish Cancer Registry. Finnish Cancer Registry. Available from: https://www.cancerregistry.fi. |

| 3. | Laurén P. The Two Histological Main Types of Gastric Carcinoma: Diffuse and So-Called Intestinal-Type Carcinoma. An Attempt at a Histo-Clinical Classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4011] [Cited by in RCA: 4389] [Article Influence: 146.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rugge M, Sugano K, Scarpignato C, Sacchi D, Oblitas WJ, Naccarato AG. Gastric cancer prevention targeted on risk assessment: Gastritis OLGA staging. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Miki K, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Yahagi N. Long-term results of gastric cancer screening using the serum pepsinogen test method among an asymptomatic middle-aged Japanese population. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:78-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Hamashima C; Systematic Review Group and Guideline Development Group for Gastric Cancer Screening Guidelines. Update version of the Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:673-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Hamashima C. Current issues and future perspectives of gastric cancer screening. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13767-13774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3622] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 10. | Rugge M, Genta RM; OLGA Group. Staging gastritis: an international proposal. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1807-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, van Dekken H, Meijer J, van Grieken NC, Kuipers EJ. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1150-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, Graham DY. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Rugge M, de Boni M, Pennelli G, de Bona M, Giacomelli L, Fassan M, Basso D, Plebani M, Graham DY. Gastritis OLGA-staging and gastric cancer risk: a twelve-year clinico-pathological follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1104-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cho SJ, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Nam BH, Kim CG, Lee JY, Ryu KW, Kim YW. Staging of intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancers with the OLGA and OLGIM staging systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1292-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Satoh K, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Hirasawa T, Kihira K, Sugano K. Assessment of atrophic gastritis using the OLGA system. Helicobacter. 2008;13:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Rugge M, Meggio A, Pravadelli C, Barbareschi M, Fassan M, Gentilini M, Zorzi M, Pretis G, Graham DY, Genta RM. Gastritis staging in the endoscopic follow-up for the secondary prevention of gastric cancer: a 5-year prospective study of 1755 patients. Gut. 2019;68:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cotruta B, Gheorghe C, Iacob R, Dumbrava M, Radu C, Bancila I, Becheanu G. The Orientation of Gastric Biopsy Samples Improves the Inter-observer Agreement of the OLGA Staging System. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2017;26:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Rugge M, Fassan M, Pizzi M, Farinati F, Sturniolo GC, Plebani M, Graham DY. Operative link for gastritis assessment vs operative link on intestinal metaplasia assessment. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4596-4601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 19. | Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3454] [Cited by in RCA: 2963] [Article Influence: 92.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene lung cancer prevention study: design, methods, participant characteristics, and compliance. The ATBC Cancer Prevention Study Group. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Varis K, Sipponen P, Laxén F, Samloff IM, Huttunen JK, Taylor PR, Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Sande N, Virtamo J, Härkönen M. Implications of serum pepsinogen I in early endoscopic diagnosis of gastric cancer and dysplasia. Helsinki Gastritis Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nieminen A, Kontto J, Puolakkainen P, Virtamo J, Kokkola A. Long-term gastric cancer risk in male smokers with atrophic corpus gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. |

| 25. | de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Song H, Ekheden IG, Zheng Z, Ericsson J, Nyrén O, Ye W. Incidence of gastric cancer among patients with gastric precancerous lesions: observational cohort study in a low risk Western population. BMJ. 2015;351:h3867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kaise M, Miwa J, Tashiro J, Ohmoto Y, Morimoto S, Kato M, Urashima M, Ikegami M, Tajiri H. The combination of serum trefoil factor 3 and pepsinogen testing is a valid non-endoscopic biomarker for predicting the presence of gastric cancer: a new marker for gastric cancer risk. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:736-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Finland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sugimoto M , Vieth M S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ