IMAGING TECHNIQUES FOR GALLBLADDER DISEASE

Conventional imaging modalities

US is widely used as a primary imaging modality for evaluating suspected gallbladder disease in patients with right upper quadrant pain or jaundice. It is a safe, non-invasive, real-time imaging modality that is cost effective, offers superior spatial resolution, and is easy to perform[3,7]. Despite its inherent sensitivity, US is limited by operator subjectivity, restricted field of view, and inexorable beam interruption by patient body habitus and contiguous bowel gas[11]. Therefore, although US can make definitive diagnoses of most gallbladder diseases, complex conditions may occasionally prove elusive[12]. For example, differentiating chronic cholecystitis from cancer in a thick-walled gallbladder or distinguishing motionless sludge from gallbladder cancer may be difficult[11,12].

Endoscopic US (EUS) is usually performed for gastrointestinal diseases, but it is also used to evaluate polyps or wall thickening of the gallbladder[13,14]. EUS-enabled gallbladder assessments are more accurate, because a high-frequency transducer (5-12 MHz) is closely applied, without interposition of other anatomic structures[14,15]. However, the invasiveness of EUS procedures, their low tolerability, high cost, longer duration, and need for sedation are all drawbacks and it is not routinely used for evaluation of the gallbladder[16].

Given the increasing global usage and improved imaging quality of CT, it has also become a primary imaging modality for gallbladder disease. CT studies are rapid, easy to perform, and offer extra-biliary duct information simultaneously. However, radiolucent stones and radiation exposure are clear limitations.

MRI is considered a problem-solving tool, reserved for unclear gallbladder cases at US or CT[3]. As a multiparametric imaging technique, it provides high-contrast resolution of tissue and permits both anatomic and functional assessments of gallbladder/biliary tract, using contrast excreted preferentially in the bile[5]. However, MRI is still expensive and time-consuming.

Advanced imaging modalities

CEUS is an emerging imaging modality widely used to evaluate various abdominal organs. Using microbubble contrast, tissue microvascularity is thereby explored, overcoming limitations of conventional US through clearer and more accurate evaluation[11]. Microbubble contrast is safe and has a low risk of adverse effects, compared with CT or MRI contrast; and it is applicable to either transabdominal US or EUS. A real-time dynamic evaluation of CEUS has become possible due to technical advances of the contrast-specific mode with a low-mechanical index in US machine and development of second-generation US contrast agents such as SonoVue (Bracco, Milan, Italy), Definity (Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA, USA) and Sonazoid (GE healthcare, Oslo, Norway). Since Sonazoid is able to obtain both vascular phase and Kupffer phase images, which are usually obtained 10-15 minutes after injection of US contrast agent, it is widely used for evaluation of hepatic focal lesion[17]. On the other hand, any kinds of US contrast agent can be used for dynamic evaluation of gallbladder. In recent years, CEUS use for gallbladder disease has brought encouraging results, especially in differentiating benign and malignant gallbladder diseases[6,7,12,15].

HRUS is a technology that uses both low- and high- frequency transducers during the gallbladder evaluation[9]. Whereas conventional transabdominal US usually only uses a low-frequency transducer from 2 to 5 MHz, HRUS can be simply applied by addition of a high-frequency transducer after routine transabdominal US. Therefore, HRUS harnesses the combined strengths of low- and high-frequency transducers. High-frequency transducer offers higher image resolution, providing clearer multilayer pattern of gallbladder wall and better internal echo change of polyps than conventional US[18,19]. This improved resolution heightens the accuracy of gallbladder assessments. It has performed successfully in characterizing gallbladder polyps and in differentiating gallbladder cancer from adenomyomatosis[9,20].

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is now accepted in clinical practice as one of the advanced MRI sequences. It reflects the degree of microscopic movement by water protons, which represents the tissue characteristics and pathologic process[10]. Generally, malignant tumors tend to show higher signal intensities on DWI, with lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, given their intense cellularity. Thus, DWI has been used in clinical practice for detecting cancer and monitoring early treatment responses of cancer[21]. In the gallbladder disease, DWI also advances our diagnostic capability in distinguishing benign and malignant diseases[10,22-24].

IMAGING APPEARANCES OF BENIGN GALLBLADDER DISEASES

Benign gallbladder diseases may be categorized according to imaging appearances as intraluminal lesions, localized or diffuse wall thickening, and miscellaneous appearances.

Intraluminal lesions of gallbladder

Intraluminal lesions of the gallbladder are typically detected by US, the first and second most common being gallstones and polyps[25]. Such lesions must be differentiated from polypoid type of the gallbladder cancer. Tumefactive sludge may also be mistaken for a gallbladder polyp or mass.

Gallstones: Gallstones are not uncommon with a prevalence of approximately 10% in the general population and are twice as likely to develop in women[5]. Increasing age, obesity, rapid weight loss, pregnancy, and estrogen are known risk factors for gallstones[2]. Most individuals affected (approximately 80%) remain asymptomatic throughout life, whereas 20% will experience symptoms of biliary colic[26]. They are classified as cholesterol or pigment stones according to composition of cholesterol, and the composition also affects their imaging features on CT or MRI[3].

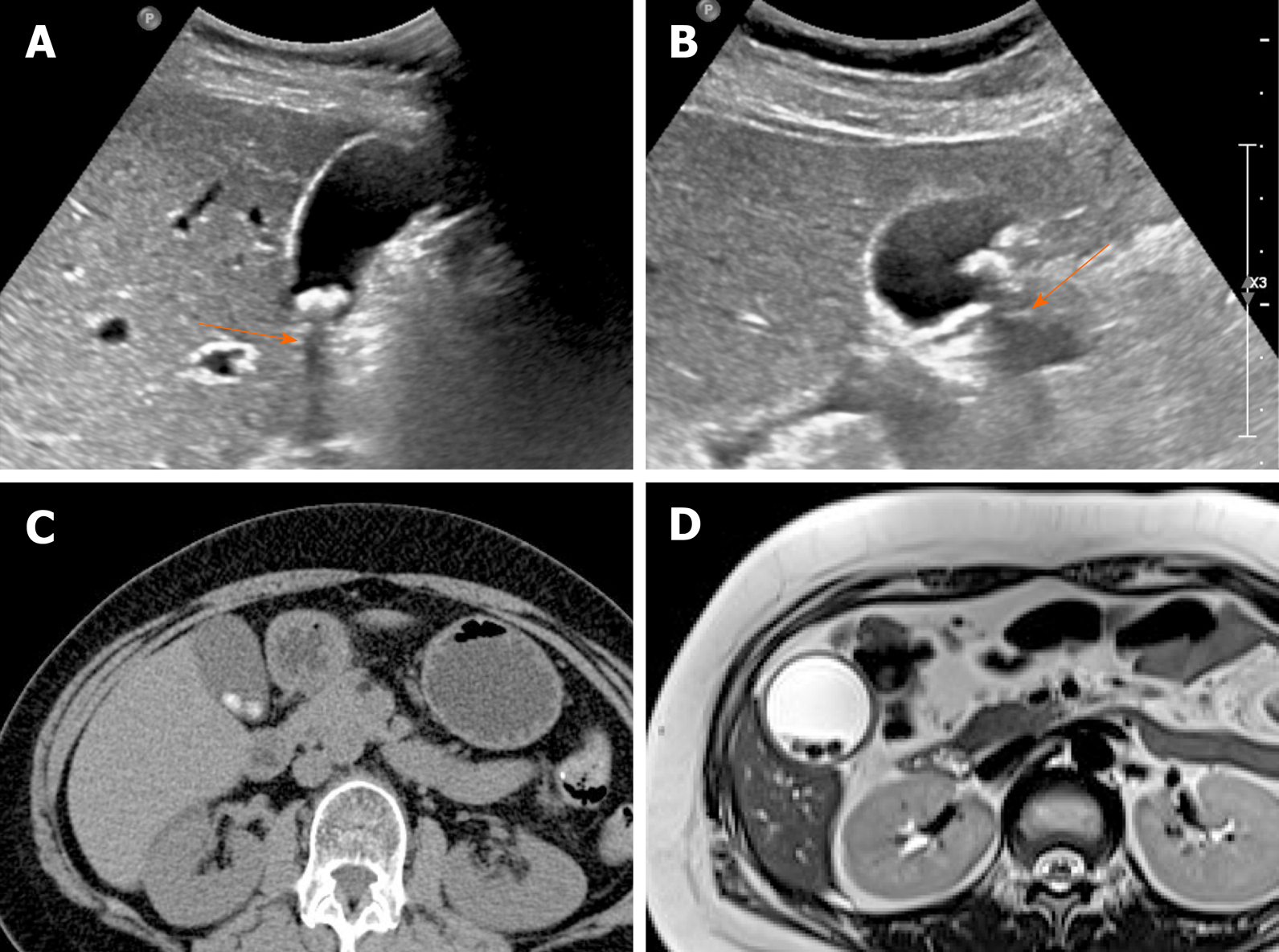

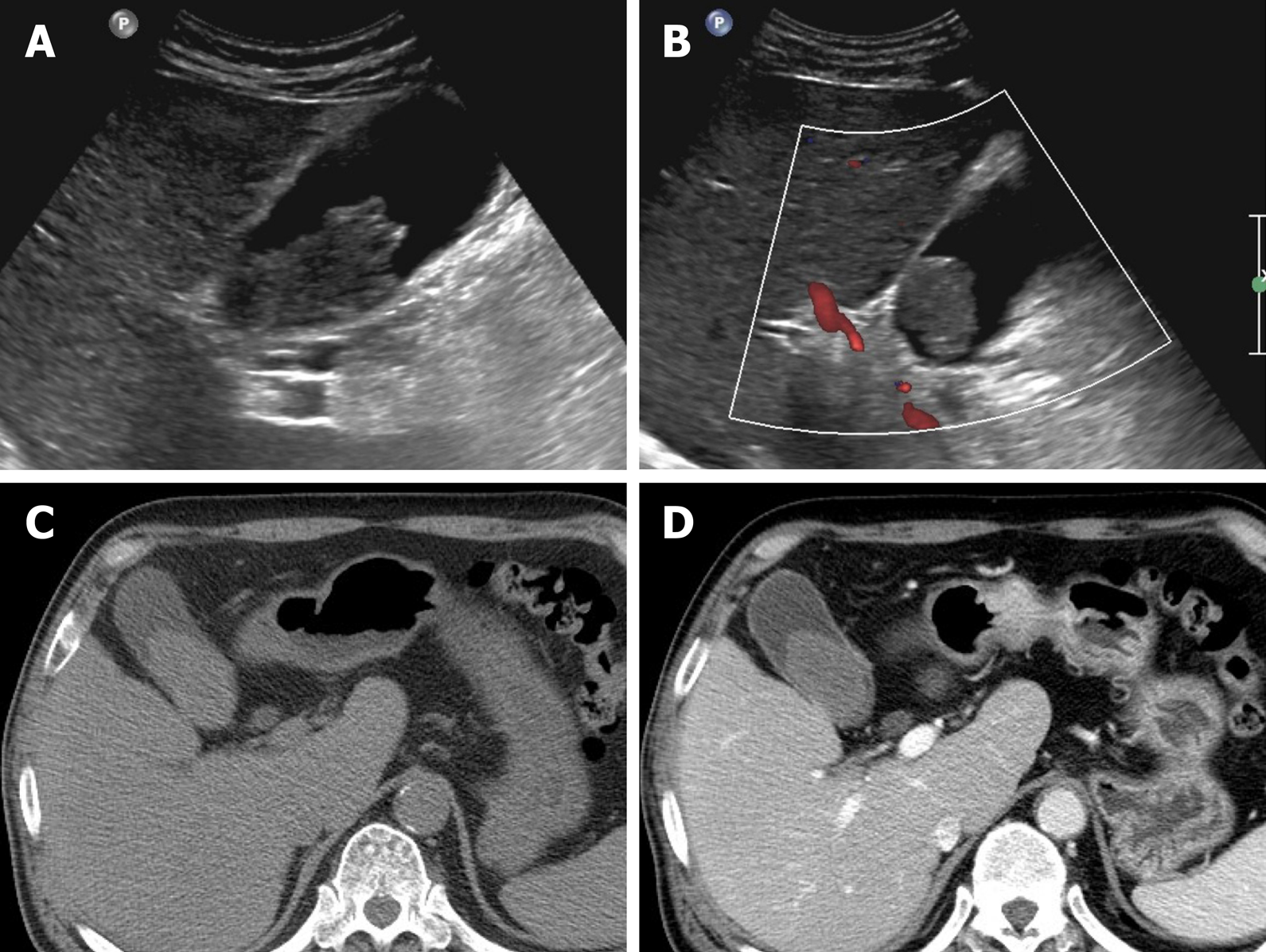

The accuracy of US in diagnosing gallstones is high up to 95%. They are usually seen as echogenic foci, with posterior acoustic shadowing, displaying gravitational dependence upon movement (Figure 1A and B)[2]. However, CT imaging of gallstones may vary. Calcified gallstones are best depicted by CT (Figure 1C), although those with high cholesterol content are iso-dense with bile and thus are difficult to detect[3]. Gallstones appear as signal voids on both T1- and T2-weighted MRI and are best appreciated on T2-weighted image, given the brightness of bile (Figure 1D)[2].

Figure 1 Gallstones.

A, B: Typical echogenic lesions of gallbladder with posterior acoustic shadowing (arrows), that move in dependent manner during supine (A) to lateral decubitus (B) positional shift on ultrasound; C, D: Calcified lesions visible on precontrast computed tomography scan (C), appearing as low signal intensity on T2-weighted image (D).

In most instances, gallstones are easily distinguished from tumorous conditions. Movability on US and lack of contrast-enhancement on CT and MRI are the chief imaging features of gallstones that rule out polyps or cancer.

Gallbladder polyp: In the gallbladder, polyps are defined as elevated (mucosal) luminal projections. The reported prevalence by transabdominal US is 3%-7%, compared with 2%-12% in cholecystectomy specimens[1,25]. They are categorized as neoplastic or non-neoplastic, based on histopathologic characteristics[27].

The most common non-neoplastic polyps are cholesterol polyps, accounting for approximately 60% of gallbladder polyps overall[27]. It is characterized by the cholesterol deposition within macrophages of the lamina propria in the gallbladder wall[1]. Multiple, small (usually 1-2 mm, < 10 mm) and rounded intraluminal lesions with smooth contours are generally identifiable by US (Figure 2). Posterior acoustic shadowing is absent, and the polyps retain fixed mural positions, despite positional change[2]. Their stalks are rarely visible, a trait affably dubbed the “ball on the wall” sign[25]. Cholesterol polyps are difficult to distinguish from surrounding bile by CT or MRI.

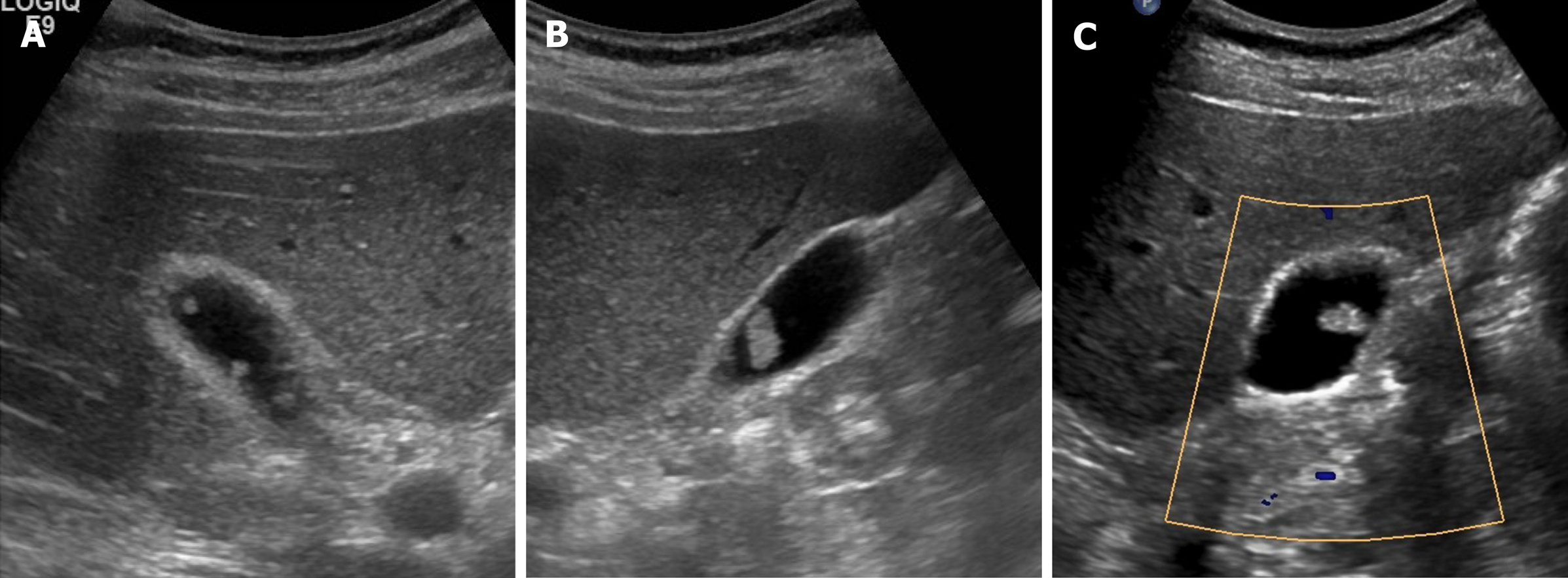

Figure 2 Cholesterol polyps.

A-C: Multiple, tiny, smooth, and hyperechoic intraluminal polypoid lesions attached to gallbladder wall, without posterior acoustic shadowing on ultrasound; internal vascularity of largest cholesterol polyp not evident by color Doppler ultrasound (C).

Adenomas are true neoplastic polyps, with a well-established potential for progression to carcinoma. They are rare, constituting only 4%-7% of all gallbladder polyps[27]. Adenomas usually occur singly and vary in size (1.0-2.5 cm)[2]. They present as sessile or pedunculated hypoechoic polyps with internal vascularity on color Doppler US and no posterior acoustic shadowing on US (Figure 3A and B)[1,25]. However, benign and malignant gallbladder polyps are not easily differentiated because they have similar echogenicity and morphology.

Figure 3 Gallbladder adenoma.

A: Single, echogenic, intraluminal polypoid lesion within distal body of gallbladder on ultrasound (US); B: Internal vascular core (arrow) demonstrable by color Doppler US; C: Homogeneous hyperenhancement of polypoid lesion on contrast-enhanced US using Sonovue, with intact gallbladder wall and no evidence of invasion [cholecystectomy performed due to size (> 2.5 cm) and adenoma confirmed].

A polyp > 1 cm in size is highly associated with a neoplastic polyp. Because benign gallbladder polyps are typically < 1 cm, those that are large-sized (> 1 cm) or rapidly growing must be regarded as potentially malignant[2]. However, considering the moderate diagnostic accuracy entailed, polyp size of 1cm is insufficient to indicate cholecystectomy for gallbladder polyps[28].

In evaluating gallbladder polyps, HRUS is more beneficial than conventional US, depicting more clearly the internal echoes[9]. Neoplastic polyps appear as single, sizeable (> 1 cm) hypoechoic polyps with sessile/lobulated contours, internal hypoechoic foci, and vascularized core on color Doppler US. Non-neoplastic polyps are instead multiple, small (< 1 cm), and smooth-surfaced iso-to hyperechoic proliferations, with internal hyperechoic foci[9,29].

CEUS also provides useful information with enhancement intensity and pattern in the characterization of cholesterol polyps, adenomas, and gallbladder cancers. Benign gallbladder polyps generally show homogeneous enhancement, and the gallbladder wall is intact, without evidence of nearby invasion[7,11]. Enhancement intensity and stalk width aid in differentiating adenomas and cholesterol polyps. Adenomas are apt to have broader stalks and show hyperenhancement during arterial phase (Figure 3C), compared with the iso-enhancement that cholesterol polyps tend to display (Figure 4)[30]. On CEUS, the appearance of gallbladder cancer varies. Hyperenhancement and rapid washout of contrast within 35 s have been reported as highly suspicious of malignancy[12].

Figure 4 Cholesterol polyp.

A: Single, echogenic, broad-based, mass-like lesion in proximal body of gallbladder on ultrasound; B: Internal vascularity not evident by color Doppler ultrasound; C: Small enhancing intraluminal lesion of gallbladder on computed tomography; D: no broad base, and mosaic pattern of weak enhancement revealed by contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound using Sonovue (lesion confirmed as cholesterol polyp).

On CT and MRI, adenomas are seen as small enhancing polypoid lesion in the gallbladder, similar to polypoid type of gallbladder cancer[1]. Still, adenomas tend to be more homogeneous in texture, retaining space between themselves and gallbladder wall and affording a relatively normal gallbladder configuration, compared with gallbladder cancer[31]. The signal intensities of gallbladder cancers on DWI are also higher than that of benign gallbladder polyps[23,32].

Sludge: Biliary debris or sludge is composed of particulate cholesterol monohydrate or calcium bilirubinate suspended in mucous[3]. It often develops in conditions of prolonged fasting or total parenteral nutrition, because bile is subject to concentration during fasting. Sludge has a fluctuating course over time and may disappear or redevelop.

On US, sludge is typified as low echoes, without acoustic shadowing or internal vascularity, tending to layer within the gallbladder dependently, slowly shifting in accord with positional change (Figure 5)[2,3]. Aggregated sludge may appear as a mobile, echogenic, intraluminal mass (sludge ball) or as a polypoid mass (tumefactive sludge) in dependent areas of the gallbladder[3]. Sludge may show iso- or mild hyperintensity in T2-weighted MR image, displaying hyperintensity in T1-weighted image (Figure 6)[5].

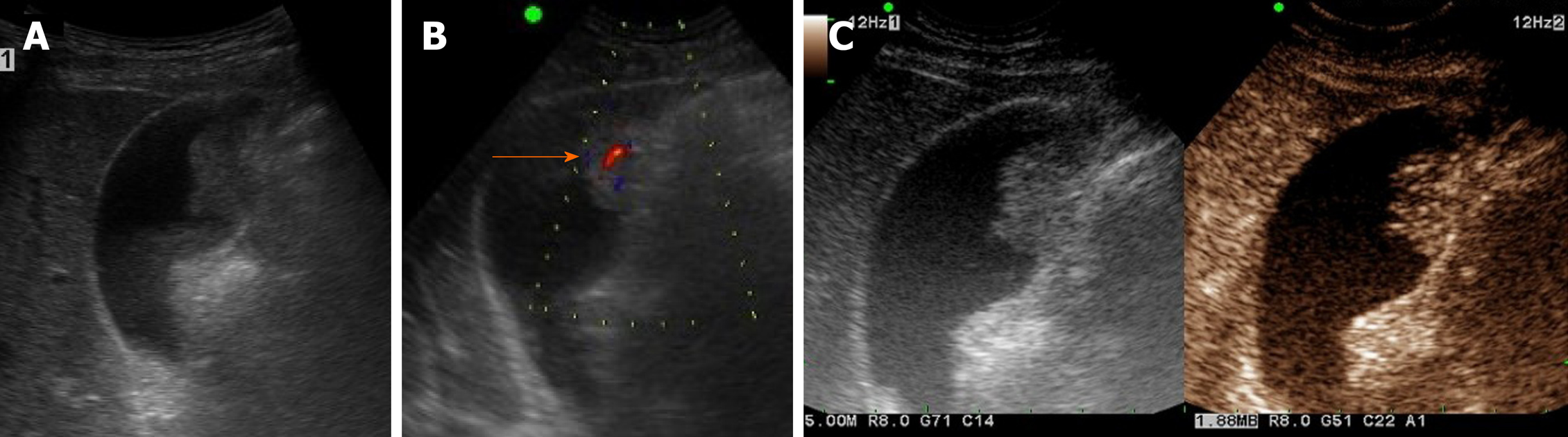

Figure 5 Sludge ball.

A, B: Ultrasound imaging of movable intraluminal echogenic mass-like gallbladder lesion, without posterior acoustic shadowing, internal vascularity absent by color Doppler ultrasound (B); C, D: high-attenuated intraluminal mass on precontrast computed tomography (C), with no enhancement on post-contrast computed tomography (D).

Figure 6 Tumefactive sludge.

A, B: Heterogeneous mixed echogenic mass occupying gallbladder on ultrasound; C: Hyperintensity (arrow) on T1-weighted image; D: Mild hyperintensity (arrow) on T2-weighted image. This lesion disappeared in follow-up images (not shown).

Occasionally, tumefactive sludge may simulate a gallbladder polyp or a polypoid gallbladder cancer. The absence of vascularity on color Doppler US is pivotal in ruling out cancer (Figure 5B)[1]. However, 14% of tumefactive sludge diagnosed on US may coexist with gallbladder malignancy[33]. Hence, repeat US examination should be done to ensure its resolution, or further evaluation by CT or MRI should be pursued to exclude an underlying mass. On MRI, the absence of dynamic enhancement and lack of diffusion restriction help differentiate tumefactive sludge from gallbladder cancer[34].

Localized thickening of gallbladder wall

A thickened gallbladder wall is a frequently encountered imaging feature in clinical practice. It is seen in various benign conditions, as well as in gallbladder cancer[16,35]. Although notorious for its poor prognosis, the 5-year survival rate of gallbladder cancer is as high as 90% if detected and treated at an early stage such as when the tumor is confined to gallbladder wall[36,37]. Superficial or infiltrating type of gallbladder cancer typically presents as gallbladder wall thickening. Consequently, early and accurate differentiation of gallbladder cancer from other benign gallbladder diseases that present with wall thickening is critical.

In this section, the focus is on benign diseases of gallbladder in which the wall is partly thickened, especially segmental or focal (rather than diffuse) adeno-myomatosis.

Adenomyomatosis: This common and benign condition, representative of gallbladder wall thickening, has been reported in 2.0%-8.7% of cholecystectomy specimens and is more frequently identified in women than in men[5,38]. By definition, the gallbladder shows epithelial proliferation and muscular hypertrophy, with intramural mucosal invaginations through the thickened muscular layer known as Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses[39]. There are three or four morphologic types of adenomyomatosis according to the gross features and areas affected: Diffuse, annular or segmental, and focal[38]. Annular or segmental adenomyomatosis appears as a ring of circumferential gallbladder body involvement with luminal narrowing, creating an hourglass appearance[5,35]. The focal type is the most common and usually involves fundus. Focal adenomyomatosis presents as focal wall thickening or frequently a semilunar or crescentic solid mass[40]. These two types of adenomyomatosis are often confused with gallbladder cancer.

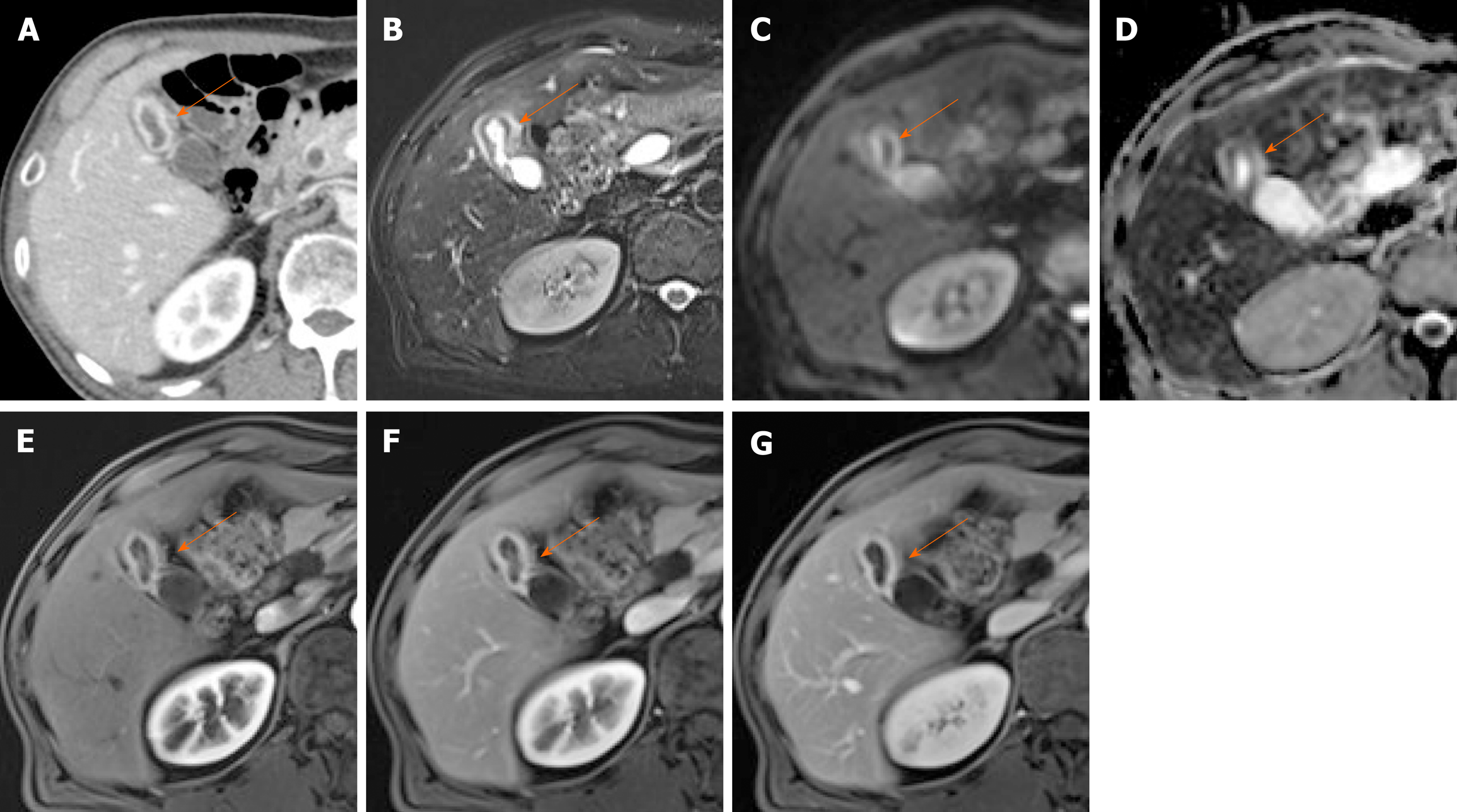

Identification of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses is crucial for an imaging diagnosis of adenomyomatosis. On US, a thickened wall with small anechoic intramural cystic spaces is seen (Figure 7)[14]. Sinuses that contain cholesterol crystals, calculi, or sludge, appear as intramural echogenic spots and show comet-tail artifact or twinkling artifact on color Doppler US (Figure 7)[38,41]. Twinkling artifact is more noticeable when using low-frequency probes[42]. On CT, adenomyomatosis also presents with thickened gallbladder wall or a mass-like lesion harboring small cystic-appearing spaces, corresponding with bile-filled Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses (Figure 7D)[43,44]. The recently described “cotton ball sign” refers to fuzzy grey enhancing dots in a thickened gallbladder wall or the dotted outer border of an enhancing inner wall layer on CT, showing high sensitivity in differentiating adenomyomatosis from gallbladder malignancy[45]. The “pearl necklace sign” is the hallmark of adenomyomatosis on MRI, denoting high signal-intensity foci of gallbladder wall on T2-weighted image (Figure 7E and Figure 8)[5,39]. Although it is highly specific for adenomyomatosis, it is not identified in 28% of cases due to small sized Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses, intramural calcification, duodenal gas, or thick bile[39].

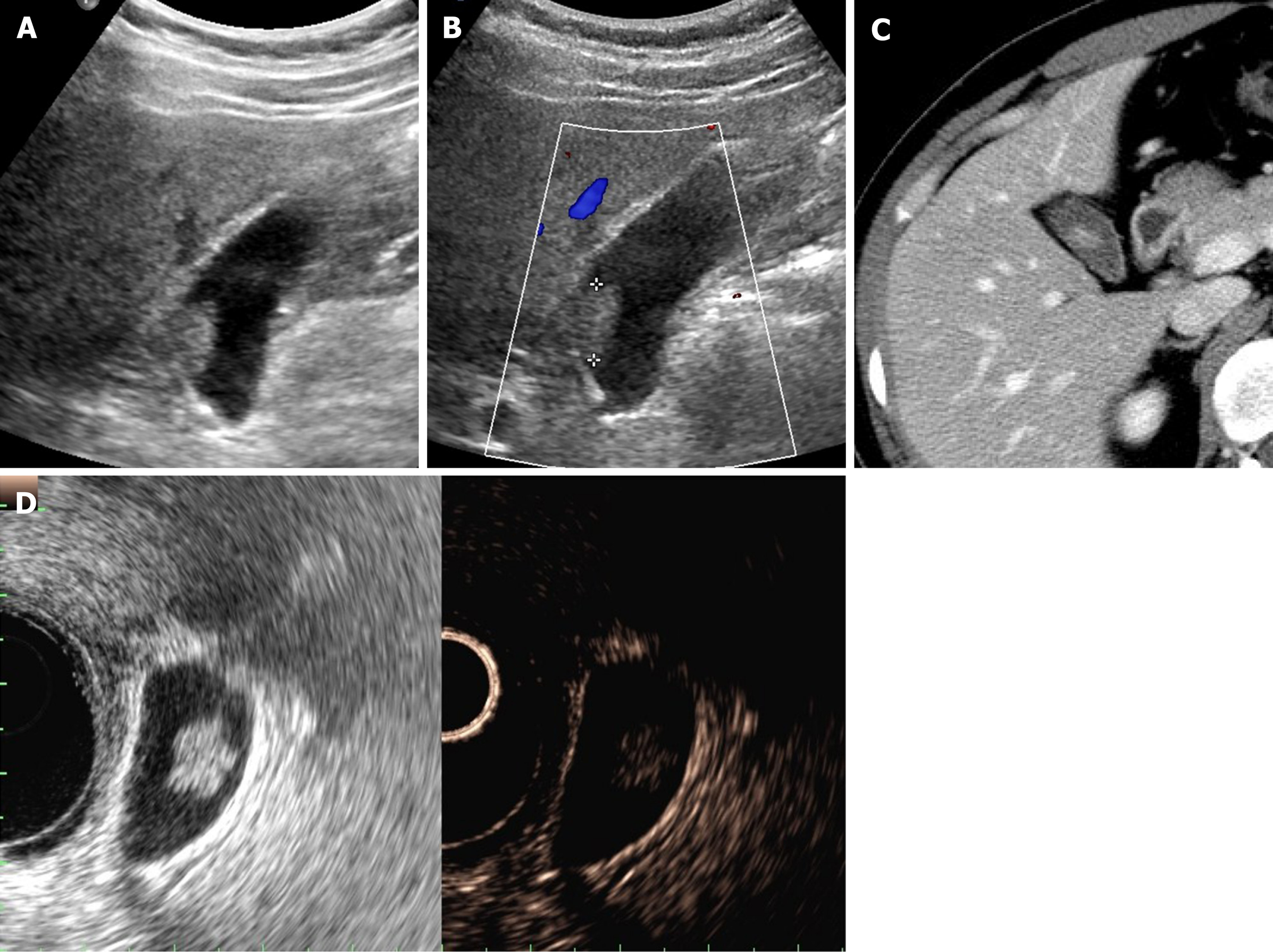

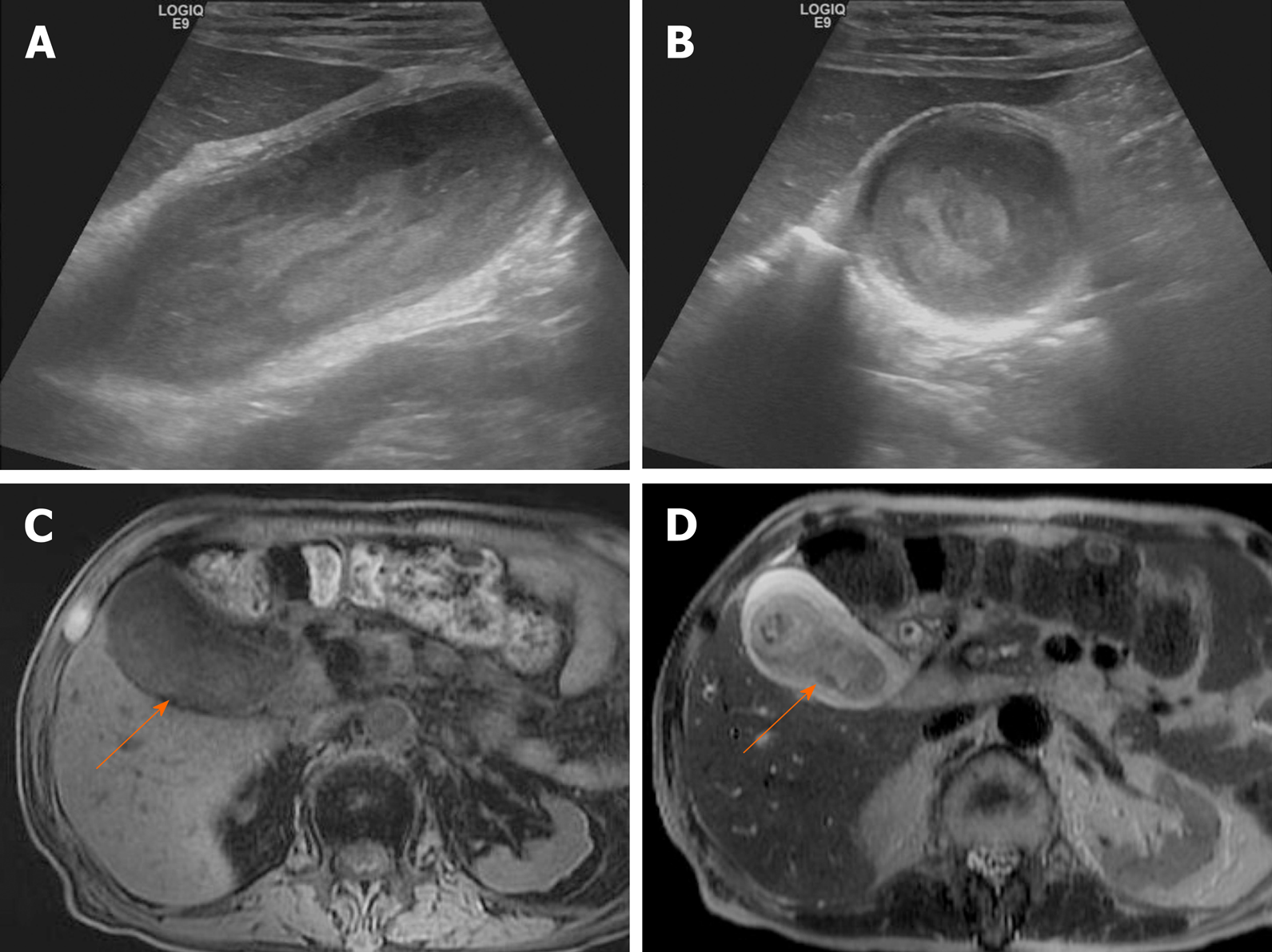

Figure 7 Segmental adenomyomatosis.

A: Mild segmental thickening of fundal gallbladder wall, with comet-tail artifacts on conventional ultrasound (US); B, C: High-resolution US (using high-frequency probe) showing small anechoic cystic inclusions (arrows) of thickened gallbladder wall (Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses) and comet-tail artifacts, superior to conventional US (B); twinkling artifacts observed on color Doppler US (C); D, E: Same intramural cystic spaces (arrows) and wall thickening of adenomyomatosis seen by computed tomography (C) and magnetic resonance imaging (D).

Figure 8 Fundal adenomyomatosis.

A, B: Oval-shaped nodular enhancing mural thickening (arrow) of fundus, with no observable cystic invaginations in axial and coronal computed tomography scans; C, D: Tiny intramural cysts clearly demonstrated within focally thickened fundal wall (arrowhead) on T2-weighted image (C) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (D), so-called “pearl necklace sign” of adenomyomatosis.

Occasionally, focal or segmental wall thickening on CT creates diagnostic dilemmas in clinical practice. Analysis of layered patterns may then be helpful. If a thickened wall shows a thicker inner enhancing layer than a hypodense outer layer or a thick enhancing single layer, gallbladder cancer is a strong possibility (Figure 9)[46]. Likewise, heterogeneous or full-thickness wall enhancement should raise suspicions of malignancy, whereas oval contours, inner layer enhancement, and intralesional cystic areas in a focally thickened wall suggest fundal adenomyomatosis (Figure 8 and 10)[47,48]. It is difficult to differentiate adenomyomatosis from gallbladder cancer on CT, because analysis of gallbladder wall layers and demonstration of intramural cysts is limited[49,50].

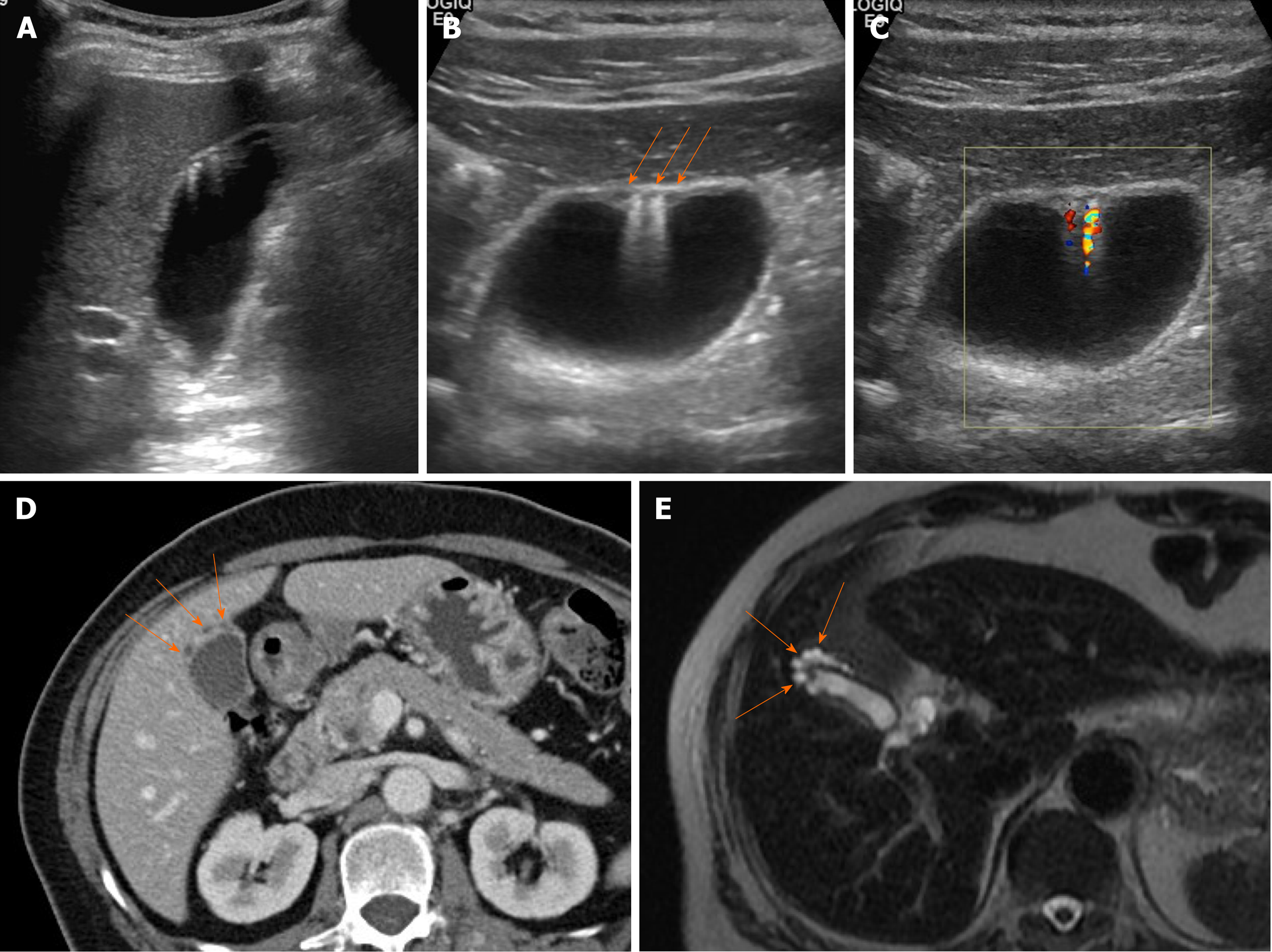

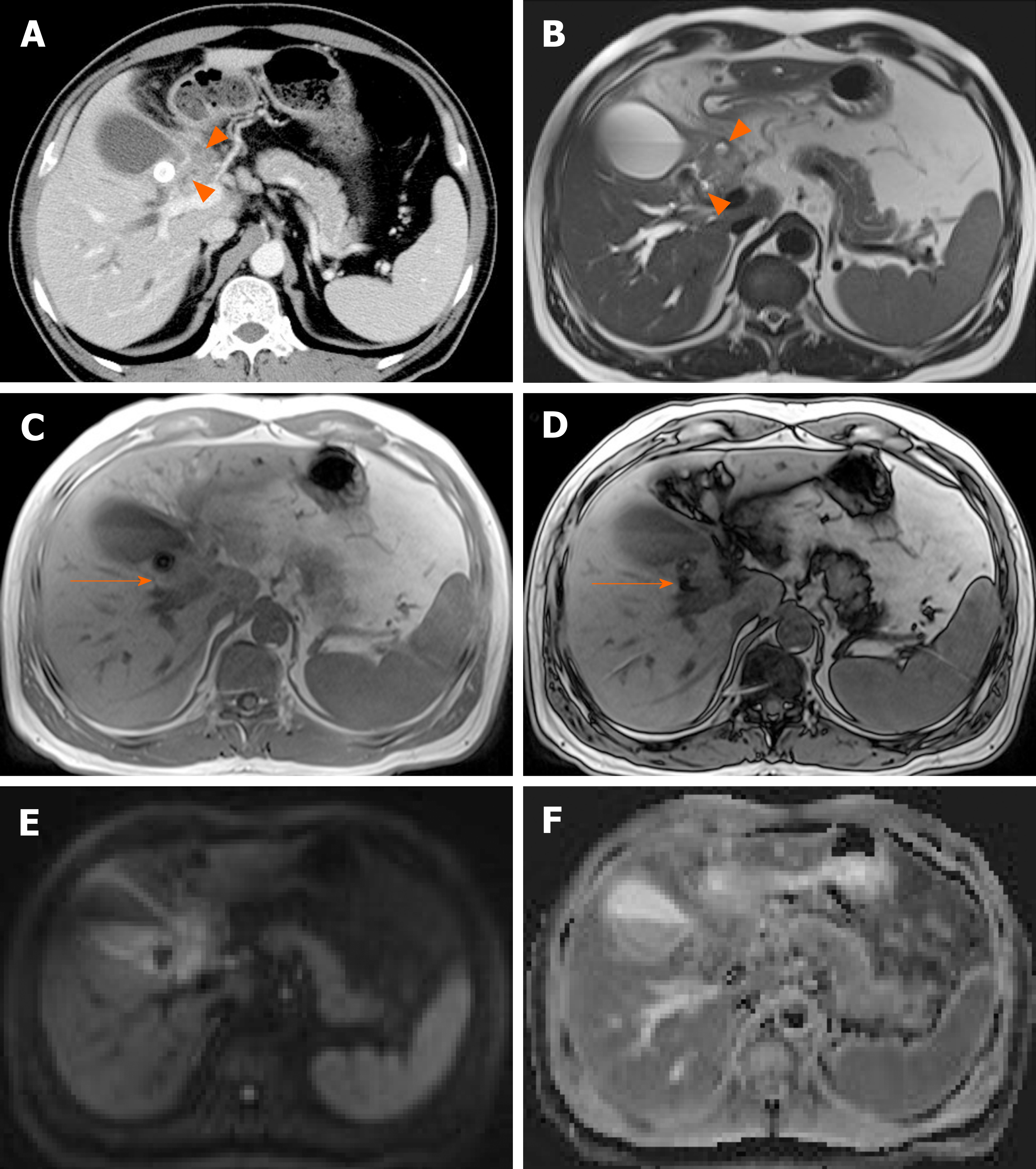

Figure 9 Cancer of gallbladder body.

A: Flat, thickened wall (arrow) with single enhancing layer of gallbladder body on computed tomography; B: No observable intramural cysts on T2-weighted image; C: Strongly enhanced lesion (arterial phase), with mild thickening of adjacent fundal wall (arrowhead) on magnetic resonance imaging; D, E: Obvious diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (D) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (E); F: Adenocarcinoma confirmed on hematoxylin and eosin staining (×100) after cholecystectomy.

Figure 10 Fundal adenomyomatosis.

A: Oval-shaped enhanced wall thickening (arrow) of gallbladder fundus on computed tomography; B: “Pearl necklace sign” unclear but suspicious intralesional hyperintensity (arrowhead) noted on T2-weighted image; C, D: No apparent diffusion restriction (arrow) on diffusion-weighted imaging (C) or apparent diffusion coefficient map (D) (diagnosed as adenomyomatosis after cholecystectomy).

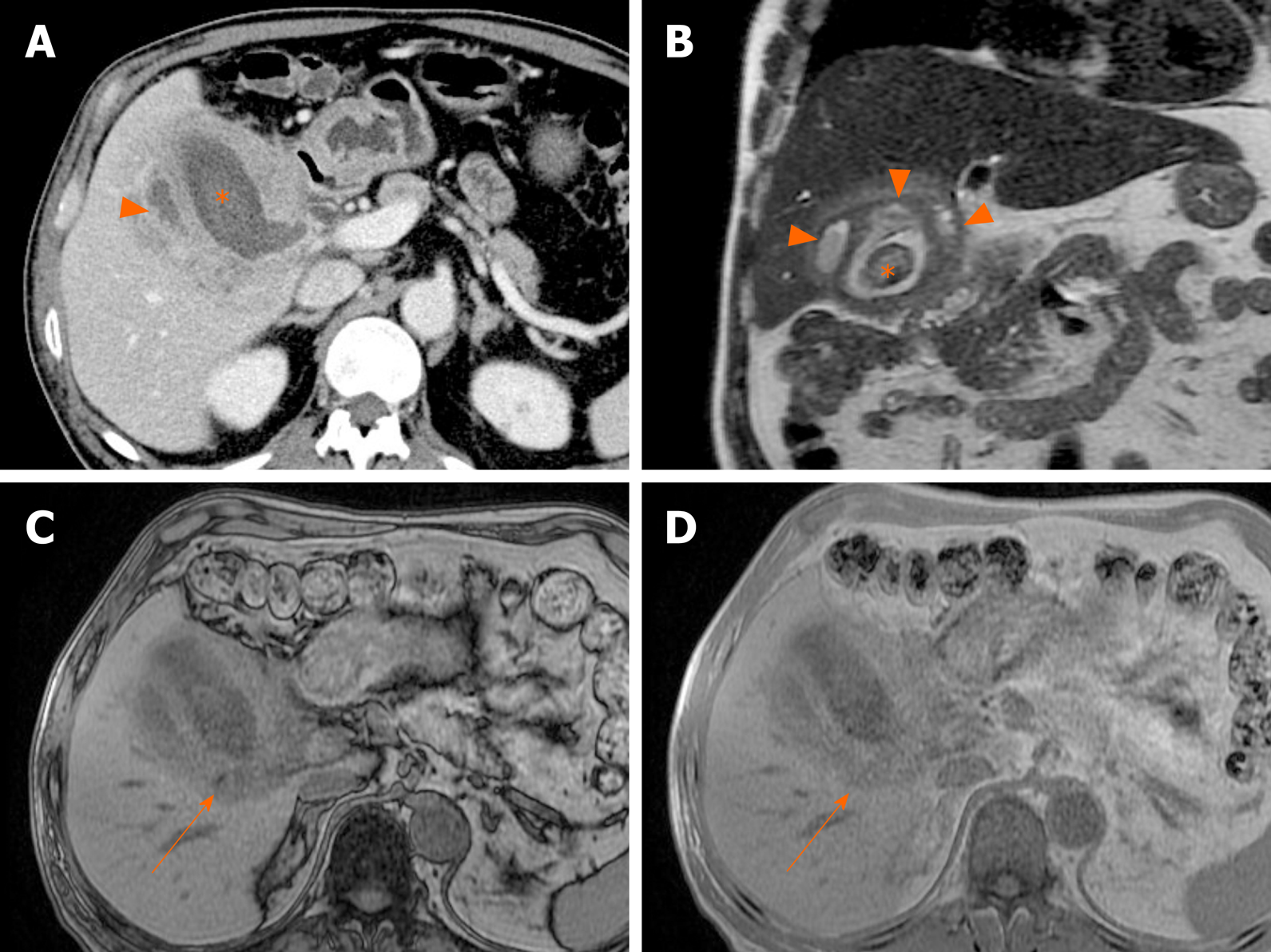

Relative to CT, HRUS and MRI perform well in differentiating these two entities[20,50,51]. HRUS offers a detailed analysis of gallbladder wall, revealing the symmetric thickening, intramural cystic spaces, and intramural echogenic foci characteristic of adenomyomatosis (Figure 7). In gallbladder cancer, there is wall discontinuity or irregular thickening of the innermost layer, irregular thickening of the outermost layer, or loss of a multilayer pattern[20,50]. DWI is helpful as well, showing higher signal intensity in malignant wall thickening than in benign wall thickening (Figure 9-11)[10,32,51]. On CEUS, early hyperenhancement, destruction of gallbladder wall, and infiltration of adjacent organs are readily suggestive of gallbladder cancer[16,52,53]. On the hand, comet-tail artifact in this setting is viewed as a reliable sign of benign gallbladder disease[54].

Figure 11 Fundal gallbladder cancer.

A: Segmental mass-like enhanced wall thickening (arrow) of gallbladder fundus on computed tomography; B, C: Intralesional cystic area absent at fundal wall thickening (arrows) on T2-weighted image (B) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (C); D, E: Mass-like fundal thickening (arrow) showing strong diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (D) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (E); F: Adenocarcinoma confirmed on hematoxylin and eosin staining (×100) after cholecystectomy.

Diffuse thickening of gallbladder wall

Diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall is frequently accompanied in inflammatory processes. This section addresses various types of cholecystitis, as well as gallbladder edema.

Acute cholecystitis: Acute inflammation is the most common gallbladder disorder. Typical clinical manifestations are right upper quadrant tenderness, pain, fever, and leukocytosis. It is usually due to gallbladder neck or cystic duct obstruction by gallstones[55]. Uncomplicated acute cholecystitis is more common and typically less dire than complicated cholecystitis or xathogranulomatous cholecystitis.

The sonographic hallmarks of acute cholecystitis are gallstones, diffuse mural edematous thickening (> 3 mm), a layered appearance of gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid accumulation, and gallbladder distension[3,55]. A positive Murphy sign is highly specific for acute cholecystitis.

CT and MRI findings include gallbladder distension, gallstones, mural edema/thickening, pericholecystic fluid accumulation, inflammatory pericholecystic fat stranding, and increased enhancement of adjacent liver parenchyma (Figure 12)[2,3]. The latter is transient, reflecting a hyperemic hepatic response to inflamed gallbladder and it is a highly specific sign, found in most instances (70%) of acute cholecystitis[5]. MRI is helpful in detecting radiolucent gallstones.

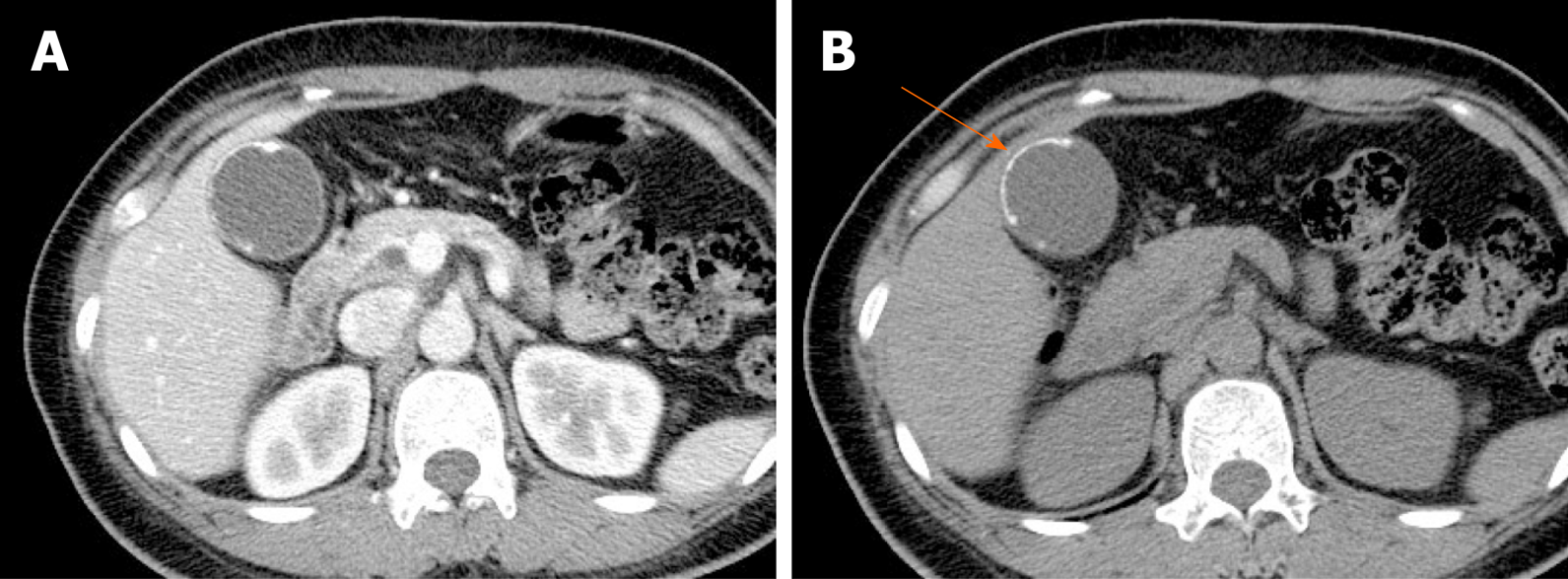

Figure 12 Acute cholecystitis.

A, B: Axial (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography scans of gallbladder showing tensile distension, diffuse mural thickening/edema, and pericholecystic fat stranding (arrows); impacted stone of cystic duct and gallstones present.

The clinical signs and symptoms of acute cholecystitis are fairly pathognomonic, facilitating the diagnosis. Even so, acute cholecystitis may mimic gallbladder cancer by virtue of diffuse mural thickening. The more important issue in clinical practice is coexistence of cholecystitis and cancer. The reported incidence of gallbladder cancer that is masked by acute cholecystitis ranges from 1%-9%[56]. Acute cholecystitis may thus be the initial presentation of an underlying gallbladder cancer. Careful investigation is necessary for evaluation of a focally enhanced wall thickening or a polypoid mass at gallbladder outlet especially in older patients with acute cholecystitis.

Complicated cholecystitis: This designation incorporates gangrenous cholecystitis, emphysematous cholecystitis, gallbladder perforation, and pericholecystic abscess. Severe mucosal ulceration or perforation may be a diagnostic challenge by US alone, often requiring complementary CT.

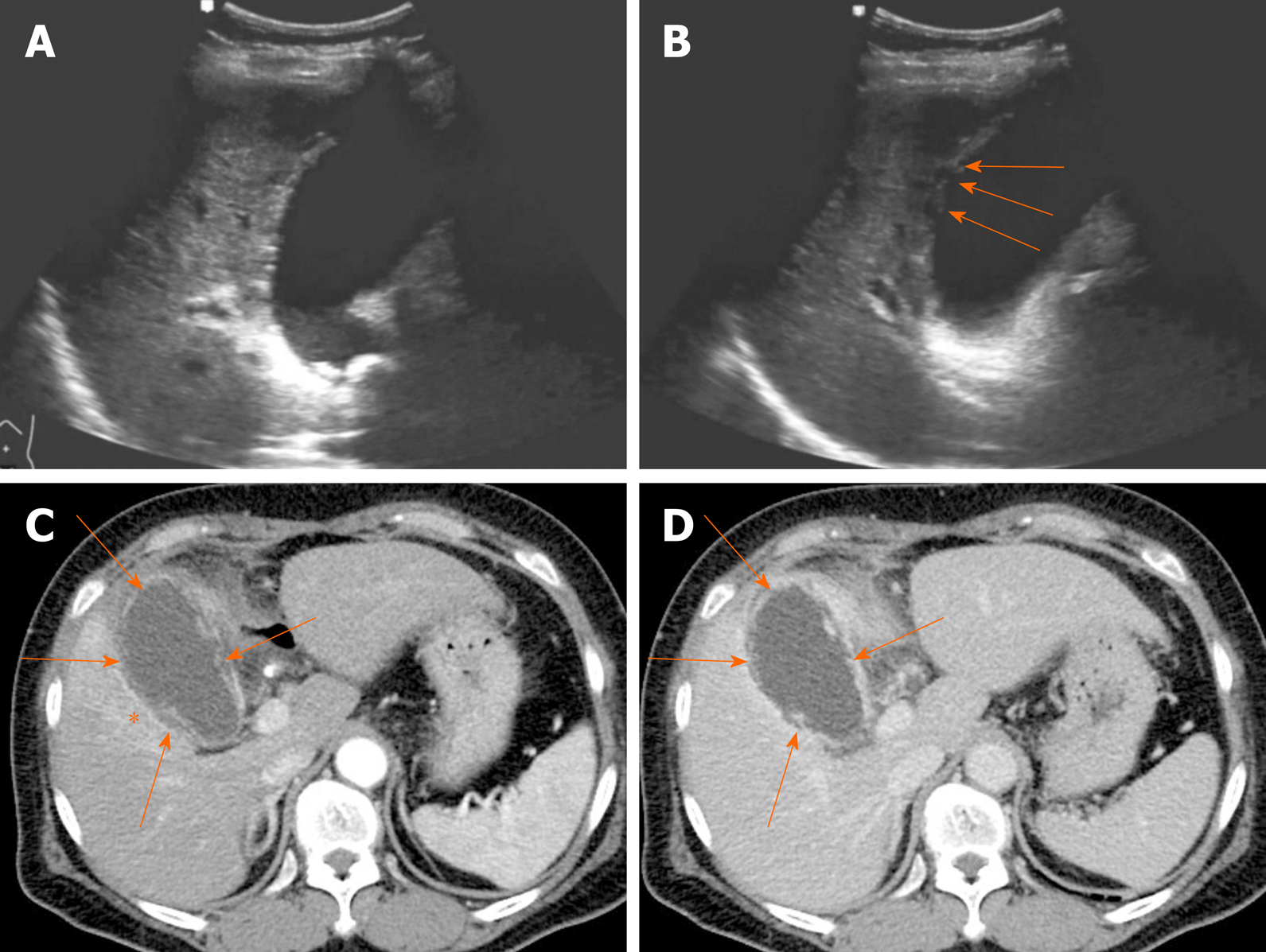

Gangrenous cholecystitis is an ominous disease, associated with high mortality and morbidity[3]. It occurs in 2%-30% of acute cholecystitis and the risk for gangrenous cholecystitis is known to increase in male patient with diabetes and leukocytosis[57-59]. Gangrenous cholecystitis is characterized by intramural hemorrhage, mucosal ulcer, and purulent debris. The US hallmarks of gangrenous cholecystitis are asymmetric gallbladder wall thickening, intraluminal membranes formed by desquamated mucosa, and complex pericholecystic fluid collections (Figure 13A and B)[2,5]. CT findings of gangrenous cholecystitis include irregular or absent of gallbladder wall, intraluminal membranes, pericholecystic abscess, lack of mural enhancement, and a greater degree of gallbladder distension with wall thickening (Figure 13C and D)[60-62]. Among them, discontinuous and/or irregular mucosal enhancement, marked gallbladder distension with decreased mural enhancement can be reliable criteria for differentiating gangrenous cholecystitis from uncomplicated acute cholecystitis[61,62]. The “interrupted rim sign” on MRI, marked by patchy enhancement of gallbladder mucosa, is useful to identify the gangrenous cholecystitis[63].

Figure 13 Gangrenous cholecystitis.

A, B: Gallbladder distension, gallstones showing posterior acoustic shadowing at the neck, and irregular mucosa detachment (arrows) on ultrasound; C, D: Arterial and portal phase computed tomography scans showing tensile gallbladder distension, diffuse mural thickening, pericholecystic fat stranding, and increased arterial enhancement of adjacent hepatic parenchyma (asterisk); irregular or partly absent gallbladder mucosal enhancement (arrows) suggesting gangrenous cholecystitis.

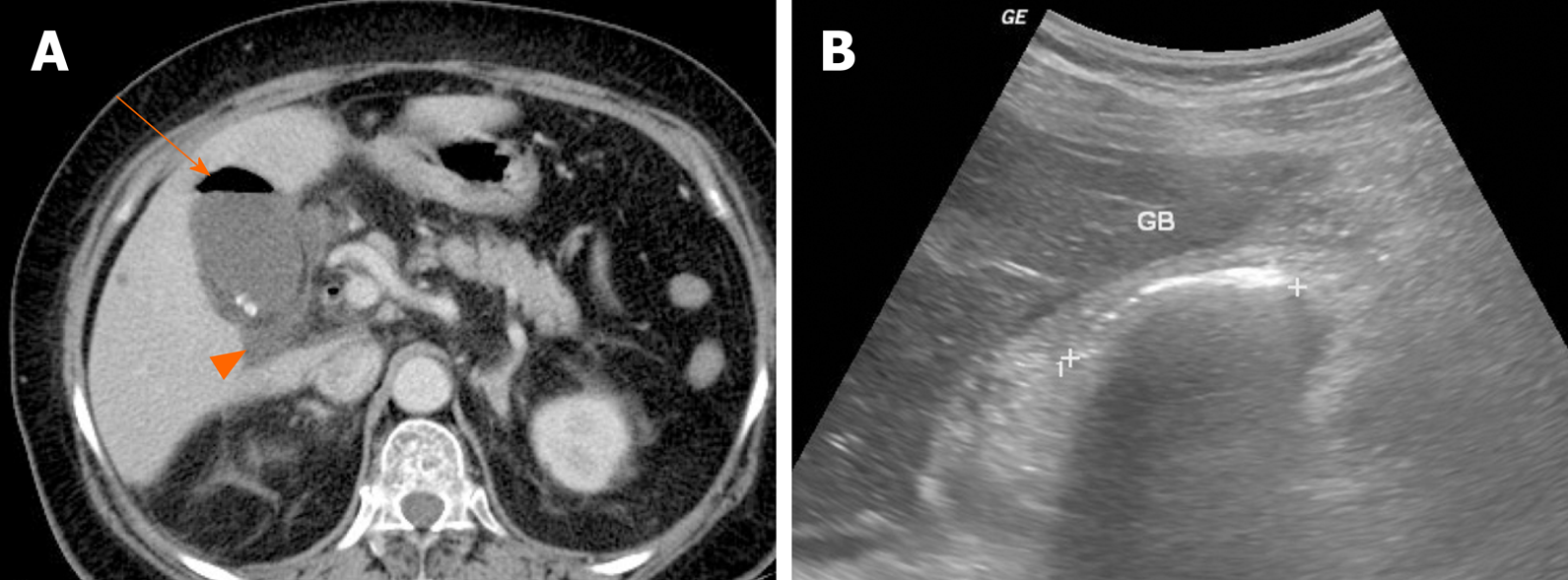

Emphysematous cholecystitis is caused by gas-forming bacteria such as Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella and is more likely to occur in diabetic patients[64]. The presence of gas within gallbladder wall or lumen is key for radiologic diagnosis (Figure 14A). Intraluminal gas produces dirty acoustic shadowing with comet-tail or ring-down artifact on US (Figure 14B). This may resemble a contracted gallbladder filled with gallstones or porcelain gallbladder[65]. CT is the most sensitive modality for emphysematous cholecystitis, capable of pinpointing the precise location of gas.

Figure 14 Emphysematous cholecystitis.

A: Readily identifiable intraluminal air (arrow) in gallbladder on computed tomography; small gallstones and pericholecystic fluid (arrowhead) present; B: Curvilinear echogenic line at gallbladder fossa, with posterior acoustic shadowing on ultrasound. GB: Gallbladder.

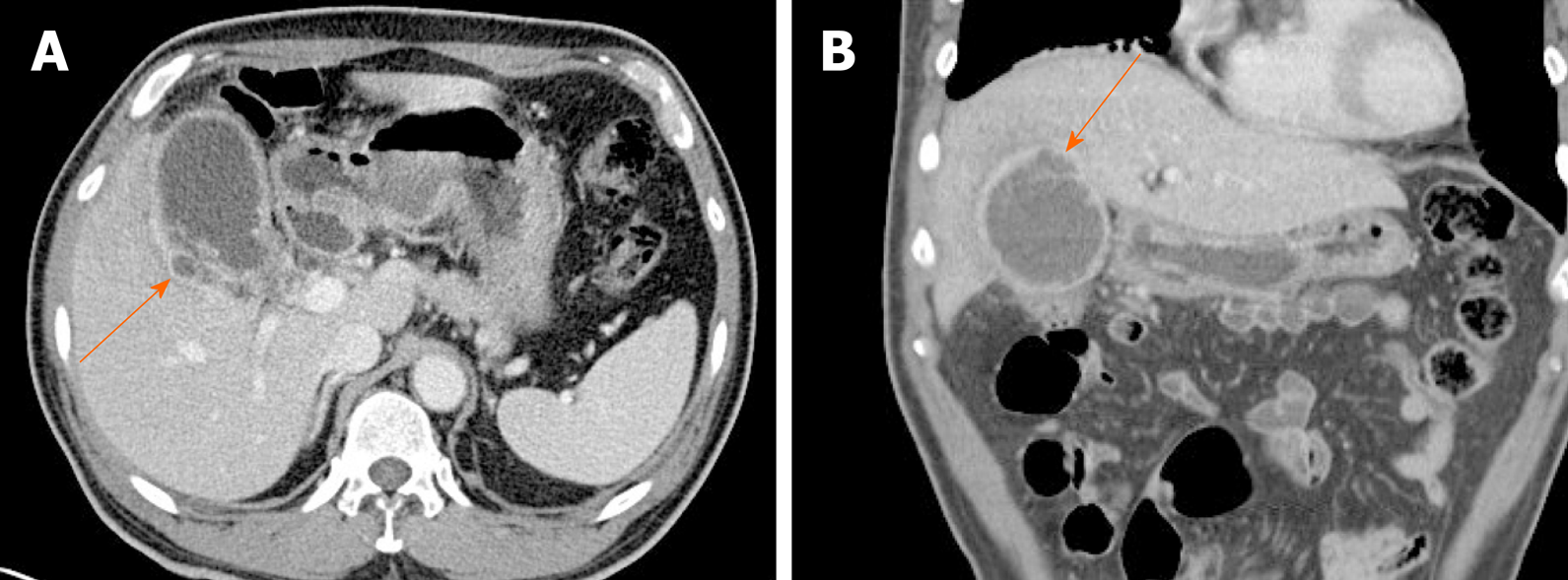

Gallbladder perforation is usually related to gangrenous cholecystitis. Owing to poor blood supply, the fundus is predisposed to perforation. On CT or MRI, the gallbladder wall is disrupted, with rim-enhancing complex fluid collections nearby (Figure 15)[2,5]. Thus, perforation results in pericholecystic abscess formation, which if confined to the liver may be mistaken for invasive gallbladder cancer, as frequently happens.

Figure 15 Gallbladder perforation.

A, B: Axial (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography scans of distended gallbladder showing diffuse, enhanced wall thickening, pericholecystic fat stranding, and irregular mucosal enhancement of acute gangrenous cholecystitis; a small rim-enhancing cystic protuberance (arrows) of nearby liver, connected to gallbladder, suggesting pericholecystic abscess due to perforation.

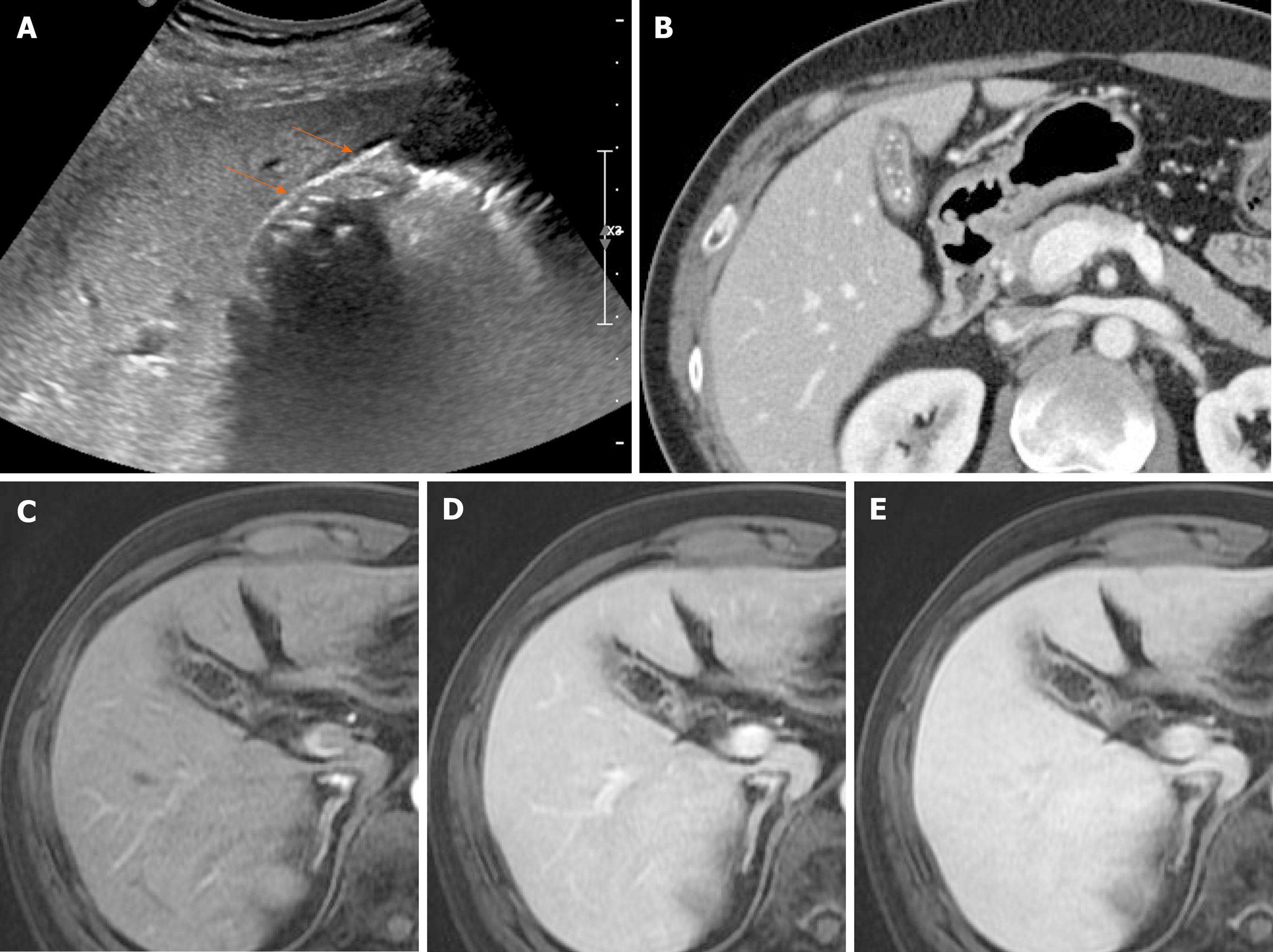

Chronic cholecystitis: Chronic cholecystitis is a common form of clinically symptomatic gallbladder disease. It is almost always associated with gallstones. The gallbladder is small and contracted, with irregularly thickened walls due to fibrotic changes. US reveals a contracted stone-filled gallbladder with posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 16A), sharing features of gangrenous cholecystitis or porcelain gallbladder. The collapsed gallbladder has a two-layered wall, which supports a diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis[44,46]. On CT, there is usually a weakly enhancing inner layer, with fuzzy margins, and a thin hypodense outer layer (Figure 16B), whereas gallbladder cancer exhibits a two-layered wall with a strongly enhancing, thick inner layer or a thick, one-layer heterogeneously enhancing wall[37,46]. In chronic cholecystitis, the wall enhancement on MRI is smooth, slow, and prolonged, as opposed to the irregular, early, and prolonged enhancement of gallbladder cancer (Figures 16 and 17)[5].

Figure 16 Chronic cholecystitis.

A: Contracted gallbladder filled with multiple echogenic gallstones, showing posterior acoustic shadowing on ultrasound, the two-layered wall (arrows) still preserved; B: Collapsed gallbladder with tiny radiopaque gallstones and diffusely thickened wall, marked by weakly enhancing inner layer with fuzzy margins and thin hypodense outer layer on computed tomography; C-E: Smooth, slow, and prolonged enhancement of gallbladder wall during dynamic-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 17 Gallbladder cancer.

A, B: Fundal chamber of bicameral gallbladder, with segmental enhanced wall thickening (arrow) on computed tomography; no observable intramural cysts on T2-weighted image; C, D: Obvious diffusion restriction (arrow) on diffusion-weighted imaging (C) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (D); E-G: Irregular, early, and prolonged strong enhancement (arrow) during dynamic-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: This uncommon chronic inflammatory disorder of the gallbladder is characterized by accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages and mixed inflammatory cell infiltrates of gallbladder wall[66]. There is a male predilection (2:1 ratio), and 80% of cases are associated with gallstones[67].

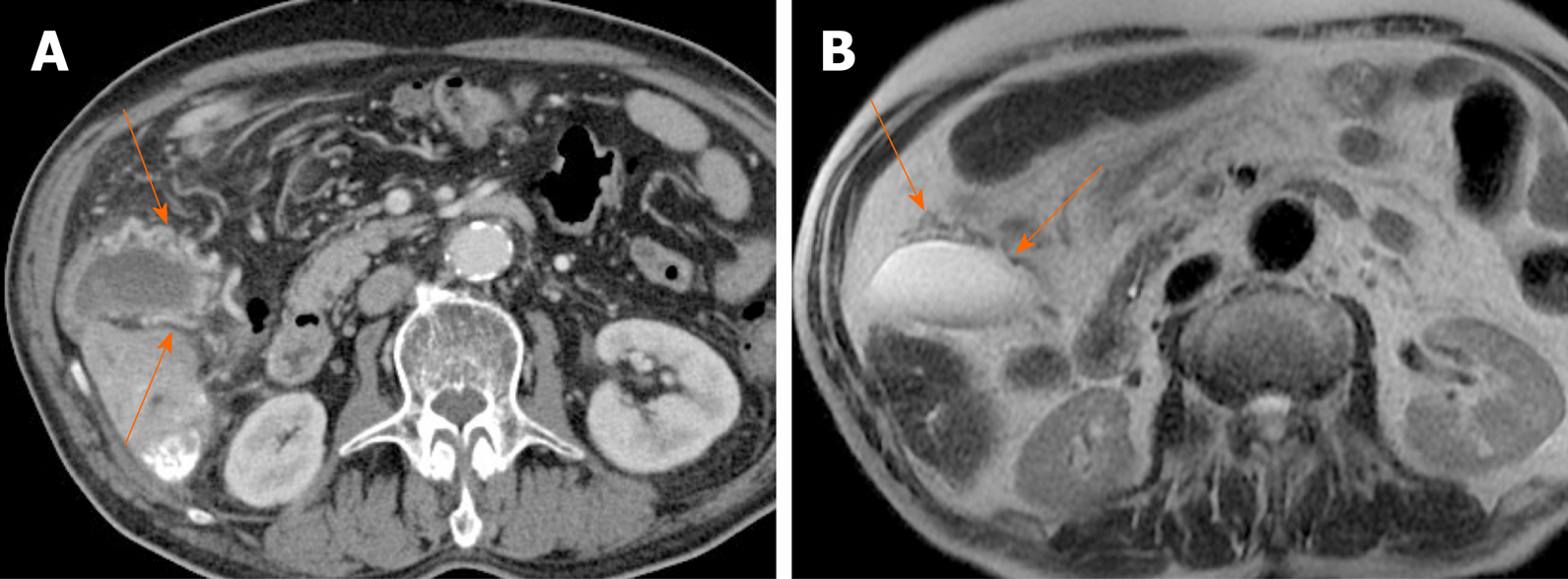

Common imaging features are diffuse thickening of gallbladder wall, presence of gallstones, continuous mucosal linearity, and intramural hypodense nodules or bands on US or CT (Figure 18 and 19)[68-71]. Intramural nodules within a thickened gallbladder wall indicative of abscess or xanthogranuloma formation, is an important imaging sign[68]. However, the diffuse wall thickening of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis is easily confused with that of gallbladder cancer. If there is severe proliferative fibrosis of the gallbladder and surrounding structures, it is especially difficult to differentiate between the two diseases based on CT alone[71,72].

Figure 18 Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis.

A: Computed tomography scan of distended gallbladder with impacted gallstone at neck, showing segmental wall thickening of neck and proximal body and small hypodense intramural nodules (arrowheads); B: High signal intensity (arrowheads) of such abscesses or xanthogranulomas on T2-weighted image; C and D: Easily identifiable fat (arrow) within thickened wall by in-phase and opposed-phase chemical shift imaging; E and F: Mild diffusion restriction of wall thickening on diffusion-weighted imaging (E) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (F), less obvious than in gallbladder cancer.

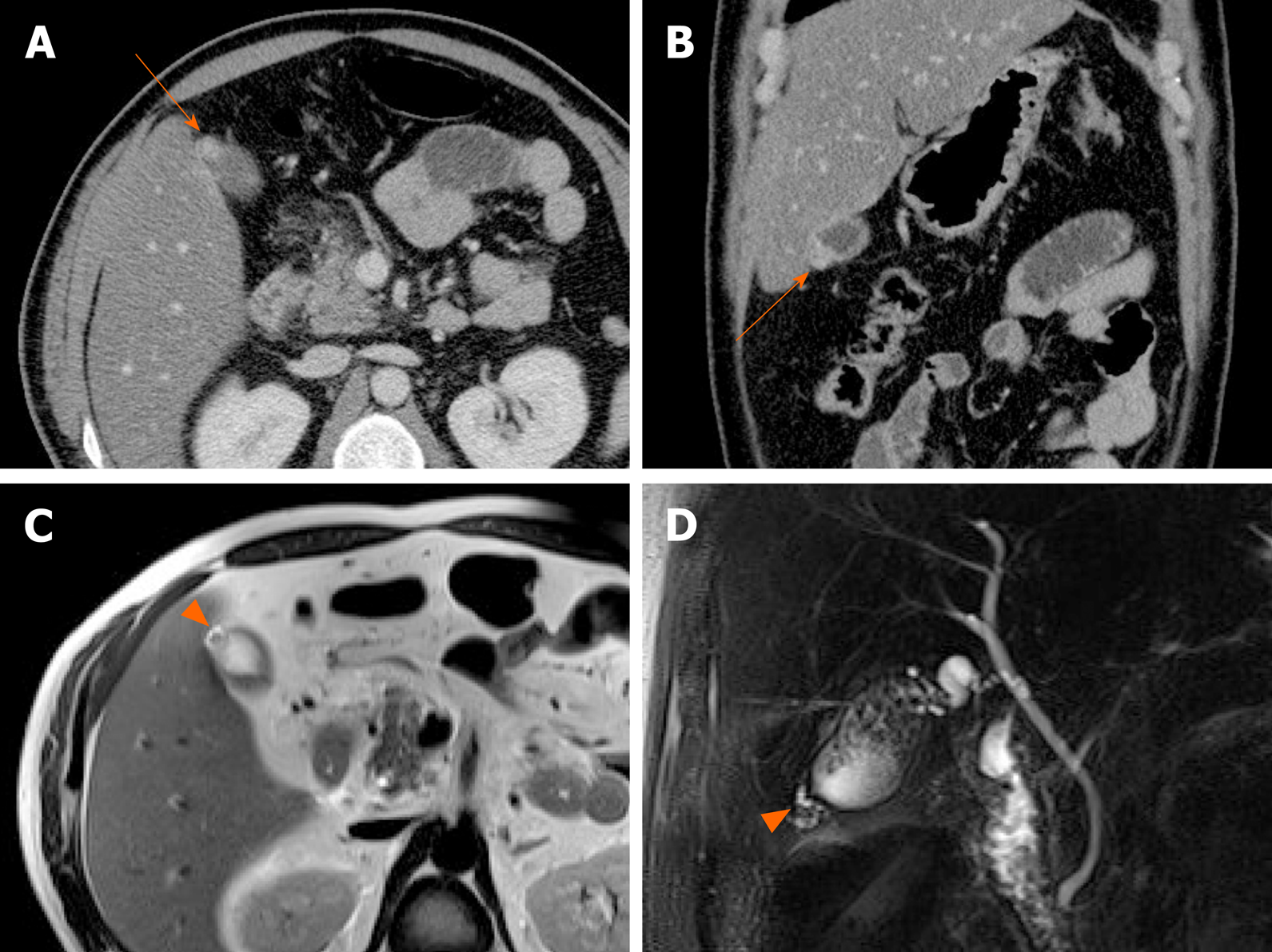

Figure 19 Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis.

A, B: Diffuse, severe wall thickening, continuous mucosal line, and small gallstone (asterisk) on computed tomography (A) and T2-weighted image (B) of gallbladder, with small intramural abscesses (arrowheads) of thickened wall; C, D: Signal drop in fat component (arrow) on opposed-phase (C) rather than in-phase (D) imaging.

MRI shows continuity of the enhancing mucosal line and high intramural signal intensity on T2-weighted image, corresponding with the hypodense intramural nodules detectable on CT (Figure 18 and 19)[5,22,66,73]. In-phase and opposed-phase chemical shift imaging also helps delineate fat content within the thickened wall (Figure 18C and D, Figure 19C and D), confirming infiltration of cholesterol-bearing foam cells[69,73]. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis shows less diffusion restriction as well, displaying a higher mean ADC value than gallbladder cancer (Figure 18E and F)[22].

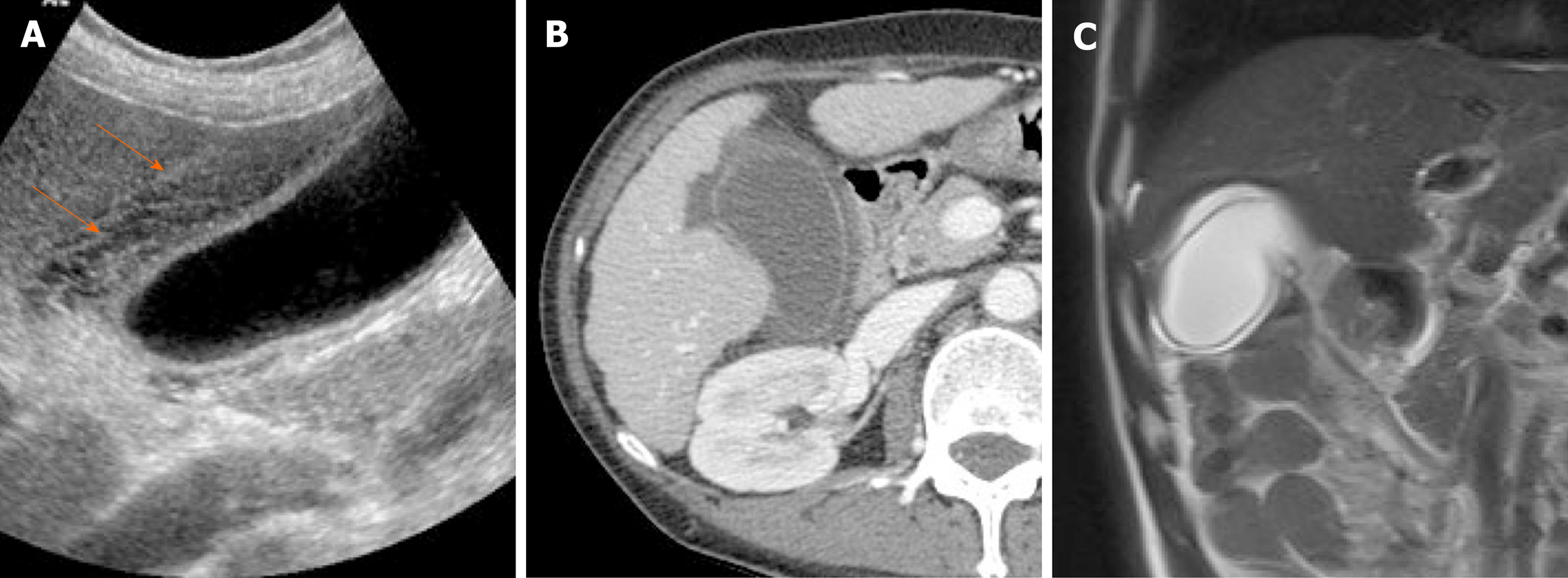

Gallbladder edema: A diffusely thickened, edematous gallbladder wall is easily misdiagnosed as acute cholecystitis. Various pathologic conditions and systemic diseases, such as cirrhosis, acute hepatitis, renal failure, hypoproteinemia, congestive heart failure, and sepsis, are frequent causes of gallbladder edema[35,74]. A multilayered, meshwork pattern is the distinctive feature on US (Figure 20A)[75]. CT typically show hypodense thickening of subserosal layer (Figure 20). Compared with acute cholecystitis, gallbladder distension, mucosal thickening, and adjacent inflammatory changes in the surrounding tissue are lacking.

Figure 20 Gallbladder edema.

A: Distention and diffuse mural thickening of gallbladder with mesh-like multilayered wall pattern (arrows) on ultrasound; B: Intact inner mucosal layer and diffusely thickened, low-attenuated subserosal layer on computed tomography; C: Diffusely edematous, thickened gallbladder showing hyperintensity on T2-weighted image.

Miscellaneous appearances

Porcelain gallbladder: Mural calcifications are the hallmark of porcelain gallbladder, which is thought to result from chronic inflammation[76]. This condition has received considerable attention, based on a heightened risk (up to 60%) of gallbladder cancer. However, recent studies have indicated a much lower rate (6%)[76-78].

The calcifications vary, ranging from focal plaques within the mucosal layer to full-thickness involvement that replaces the muscular layer[2,3]. By US, a curvilinear echogenic lesion with posterior shadowing is evident in gallbladder fossa. As already mentioned, chronic calculous cholecystitis and emphysematous cholecystitis must be excluded. CT is the preferred modality, depicting the mural calcification and perhaps helping to directly visualize an associated cancer (Figure 21). A large encased stone with calcific rim and attenuated bile centrally may simulate porcelain gallbladder[3].

Figure 21 Porcelain gallbladder.

A: Segmental, irregular wall thickening of gallbladder fundus on contrast-enhanced computed tomography; B: Curvilinear calcification (arrow) of fundal wall on precontrast computed tomography.

Gallbladder varices: Such venous collaterals are relatively rare in patients with portal vein hypertension, arising more often in those with extrahepatic portal vein occlusion[79]. Spontaneous rupture is unusual but may prove fatal, especially during hepatobiliary operations[80]. Both cholecystic and pericholecystic collaterals are involved. They appear as anechoic, serpentine areas within the wall or abutting the gallbladder and show corresponding venous flow on Doppler US[81]. On CT, nodular mural enhancement or numerous enhancing small vessels surrounding gallbladder wall or in the pericholecystic bed are present and show signal voids on MRI (Figure 22)[79,82].

Figure 22 Gallbladder varices.

A: tortuous enhancing vascular structures (arrows) encircling gallbladder wall on computed tomography, caused by portal vein thrombosis (not shown); B: Signal voids of varices (arrows) on T2-weighted image.